An Occult Physiology

GA 128

24 March 1911, Prague

5. The Systems of Supersensible Forces

It will be my task to-day, before we continue our studies, to present certain concepts which we shall need to use in the further development of our discussions. In this connection it will be especially important for us to come to an understanding as regards the meaning of that which we call in a spiritual-scientific, anthroposophical sense, a “physical organ,” or rather the “physical expression of an organ.” For you have already seen that we have a right to say with regard to the spleen, for example, that, as something material, the physical spleen may even be removed or become useless without thereby causing the activity of what we call “the spleen” in the anthroposophical sense to be eliminated. We must say, then, that when we have actually removed a physical organ such as this, there still remains in the organism the inner vital activity which should be carried on by the organ. From this we already see, and I beg you most earnestly to adopt this concept for all that follows, that we can think away, as it were, everything physically visible and perceptible in an organ such as this (it is not possible in the case of every organ) and yet there still remains the functioning, the activity of the organ, with the result that we must consider what then remains as belonging to what is super-sensible in the human organism. But, on the other hand, when we speak on the basis of our spiritual science about such organs as the spleen, the liver, the gall-bladder, the kidneys, the lungs, and the like, we are by no means referring when using these names, to what we can see physically, but rather to force-systems that are in reality of a super-sensible nature. For this reason, precisely in the case of such an organ as the spleen we must think, to begin with, when we speak about it from the spiritual-scientific standpoint, of a force-system not physically visible to external sight.

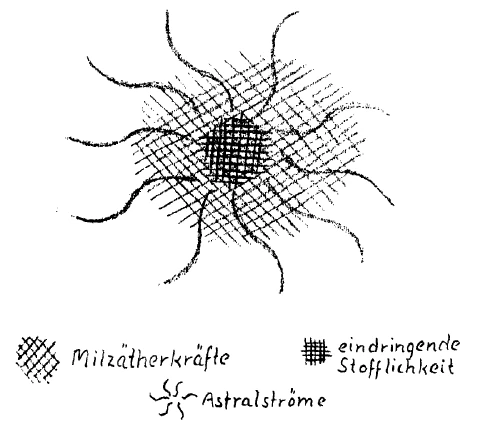

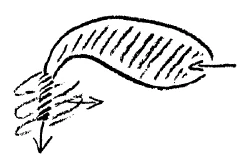

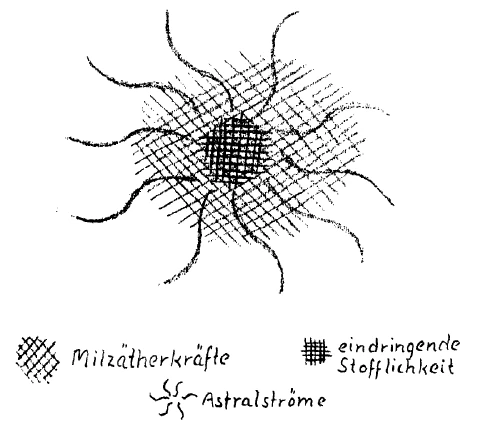

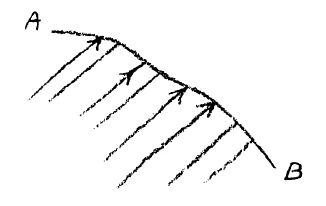

Let us then, in the first sketch that I shall draw here, think of a force-system not physically visible. This would represent a force-system visible only to super-sensible vision; and a system such as that in the region of the spleen, for example, would be visible only as a super-sensible force-system. Now if we bear in mind that, in the actual human organism which we have directly before us, this super-sensible force-system is filled out with physical matter, we must ask ourselves how we shall have to think of the relationship between it and that which is sense-perceptible matter.

I am sure it will not be difficult for you to believe that forces not visible to the senses can traverse space. One need only recall, for example, the following: Anyone who had never heard anything about the reality of air in a bottle would be rather surprised if we were to place an empty bottle on a table and tightly insert a funnel in it, when, on pouring water quickly into the funnel the water in the funnel is held there and cannot flow down into the bottle because the latter contains air. He would then become aware of the fact that there is, indeed, in the bottle something invisible to him which holds back the water. If we imagine this concept carried somewhat further, it will not be difficult to think that space around us may likewise be completely filled with force-systems which are obviously of a super-sensible nature, moreover, of such a super-sensible nature that not only can we not cut through them with a knife, but that they cannot be affected when any physical matter such as the kidneys, embedded within these force-systems, becomes diseased. We must realise, therefore, that the relation between a super-sensible force-system of this sort and what we see as a physical-sensible organ is such that physical matter, belonging to the physical world fits itself in and, attracted by the force-centres, deposits itself within the lines of force. Through the depositing of the physical matter in the super-sensible force-system does the organ become a physical thing. We may say, therefore, that the reason why, for instance, a physical-sensible organ is visible at the place where the spleen is located is that, at this point, space is filled in a certain definite manner by force-systems which attract the material substance in such a way that this deposits itself in the form in which we see it in the external organ of the spleen when we study it anatomically.

So you may think of all the different organs in the human organism as being first planned as super-sensible organs, and then, under the influence of the most varied sorts of super-sensible force-systems, as being filled with physical matter. Hence, in these force-systems which at different points of the organism deposit physical matter within themselves, we must recognise a super-sensible organism which is differentiated within itself and which incorporates physical matter within itself in the most diverse ways. We have thus obtained, not only this one concept of the relation of the super-sensible force-systems to the physical matter deposited in the organs, but also the other concept of the process of nourishing the organism as a whole. For this process of nourishing the entire organism consists in nothing else, after all, than in so preparing the nutritive substances taken in that it is possible to convey them to the different organs, and then in the incorporating of these substances by these organs. We shall see later how this general concept regarding the process of nutrition, which appears to be a power of attraction in the different organ-systems for the nutritive substances, is related to the coming into existence of a single human being, the embryonic development of the single human being which takes place before birth. The most comprehensive concept of nutrition, accordingly, is this: that by means of a super-sensible organism, the different nutritive substances are absorbed in the greatest variety of ways.

Now we must bear clearly in mind that man's ether-body, the super-sensible member of the human organisation nearest to the physical body, is the coarsest, so to speak; but that it underlies the entire organisation as its super-sensible prototype, is differentiated within itself, and contains the most manifold sorts of force-systems, in order that it may incorporate in the greatest variety of ways the substances taken in through the process of nutrition. But, in addition to this etheric organism, which we may look upon as the nearest prototype of the human organisation, we have still a higher member in the so-called astral body. (Just how these things are inter-related we shall see in the course of these lectures.) The astral body can become a member of the organism only when the physical and the etheric organisms have each been prepared according to its disposition. The astral body is that which presupposes both the other organisms. We have, moreover, the ego; so that the human being is composed of a union of these four members.

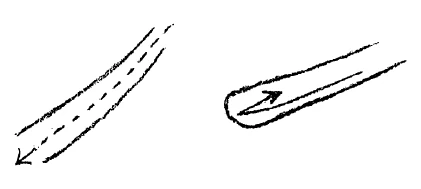

Now, we may picture to ourselves that even in the ether-body itself there are certain force-systems that attract to themselves particles of food taken in, and then shape these in quite definite ways in the physical organism. But we can also picture to ourselves that such a force-system is determined not only by the ether-body but also by the astral body, and that the latter sends its forces into the ether-body. If accordingly we first think away the physical organ and conceive the physical matter as cut out we have, first, the etheric force-system and next the astral force-system, which in turn permeates the etheric force-system in a perfectly definite manner. Indeed we may also conceive radiations passing down into these from the ego.

Now there may be organs which are so incorporated in the whole organism that their essential characteristic, for example, lies in the fact that the etheric currents in them are, as yet, very indefinite. We find, therefore, if we investigate the space in which such an organ is located, that the etheric portion of the human organism in this spatial formation is very slightly differentiated in itself, contains very little in the way of force-systems; but that, to make up for this, these weak forces of the ether-body are influenced by strong astral forces. When, therefore, physical matter is incorporated into such an organ as this, the ether-body exercises only a slight force of attraction and the chief forces of attraction must be exercised by the astral body upon the organ in question. It is as if the relevant substances are brought, as it were, by the astral body into this organ. From this we see that the values of the human organs here in question vary considerably. There are certain organs which we have to recognise as being determined principally through the force-systems of the ether-body; and others which are determined, rather, through the currents or forces coming from the astral body; whereas others again are to a greater degree determined through the currents of the ego.

Now, as a result of all that has thus far been presented in these lectures, one may say that especially that organic system conveying our blood is essentially dependent upon the radiations going forth from our ego; and that the human blood, therefore, is connected essentially with the currents and radiations of the human ego. The other organ-systems, with what they contain, are determined in the greatest variety of ways by the super-sensible members of man's nature.

But the reverse situation may occur when we consider the physical body per se, which, indeed, disregarding for the moment its higher members, exhibits likewise a force-system. For it represents, to begin with, what we may conceive as the combination of all the substances taken in from the outer world which at the same time have brought into it their own inner forces, even though in a transformed condition. Thus the physical body is also a force-system; also a force-system; so that we may also imagine cases in which this physical organism with its force-system works back upon the etheric, or even upon the astral, force-system, indeed even as far back as the ego-system. Not only may we conceive that the etheric force-system is seized upon by the astral- or the ego-system, but it is equally possible that there are organic systems which are specially requisitioned by the physical force-systems, in which cases it is the physical force-systems that prevail. Organ-systems of this sort, in which the physical body preponderates over the others, and which are therefore only to a lesser degree influenced by the higher members of the human organisation—while on the other hand more strongly influenced by the laws of the physical body—these are more especially the organ-systems which serve in a very comprehensive sense as organs of secretion and excretion,1Absonderungsorgane. The term Absonderung is applied in these lectures to the process whereby various organs take out a portion of the nutritive matter and hold this for use (=secretion) and at the same time reject the rest of the matter (=excretion), either discharging this portion out of the body or passing it on to be discharged. The important aspect of the process, from the point of view of these lectures, is that of separation, implying resistance, through which alone man can become conscious of himself. Hence the term excretion is used for Absonderung except where secretion is obviously required. as glandular organs or secretory and excretory organs in general. All organs of secretion, therefore, organs which secrete substances directly in the human organism, are induced to do so—a process that has its essential significance purely in the physical world—chiefly through the forces of the physical organism. Wherever in the human body there are organs such as these, existing for the special purpose of being used by the physical organism to secrete substances, such organs, when they become ill or are removed—which means when they become useless in some quite definite way—cause the ruin of the organism so that it cannot any longer continue its normal development.

In the case of an organ like the spleen, with regard to which the statement was ventured in yesterday's lecture that, when it becomes ill or in any way useless, its own function is affected less than would be true in the case of other organs, we see that it is very specially influenced by the super-sensible portions of man's nature, by the ether-body and more especially by the astral body. And we see that in the case of some other organs the physical forces predominate. The thyroid gland, which in certain disease conditions becomes enlarged into the so-called goitre, may have a very injurious influence upon the whole organism, because the activities which it especially has to manifest are such that what it brings about in the physical world as a physical process is absolutely essential to the general economy of the human organism.

Now there may be organs that are to a very high degree dependent upon the other, the super-sensible force-systems of the human organism, but which are none the less closely bound to the physical organism and are induced through its forces to secrete physical matter. Such organs, for example, are the liver and the kidneys. These are organs which, like the spleen, are dependent upon the super-sensible members of the human organisation, the ether-body and the astral body, but which are seized upon by the forces of the physical organism, and are drawn downward in their activities even into the forces of the physical organism. It is, therefore, of far greater importance for them to be in a healthy condition as physical organs in the human organism than for other organs, those, for example, in which conditions are such that the physical demands are far outweighed by what is derived from the other members, so that we have in the spleen an organ of which we can say that it is a very spiritual organ, that is, the physical part of this organ is its least significant part. In occult literature which has come forth from circles where something was really known about these matters, the spleen has always been looked upon as a particularly spiritual organ and is described as such.

Thus we have now arrived at what we may call the concept of the “complete organ.” An organ, as such, may be looked upon as a super-sensible force-system; although physical-sensible substances are stored up, as it were, in the organs through the entire process of nutrition. Another concept we must acquire raises this question: What is the significance in general of taking in something, whether it be a physical substance or what is received through the influence of our soul-activity; for example, through perception? And what is the significance of the excreting2See footnote, p. 79. of a physical substance?

Let us begin with the process of excretion in its most inclusive sense. We know, in the first place, that from the food taken, a large portion of the material substance is excreted. We know, further, that carbonic acid is excreted from the human organism through the lungs; that, after the blood has been sent out of the heart and through the lungs in order to be renewed, the carbonic acid is thrown off. We have, then, another excretory process through the kidneys, but also one through the skin. In this last process which goes on primarily in the forming of perspiration, but also in everything occurring by way of the skin which must be classed as an excretory process, we have those excretory processes in the human being which take place at the outermost circumference of the body, its outermost periphery. Let us now ask ourselves the question: What is the full significance of the excretory process in the human being?

Only in the following way can we be clear as to the significance of a process of excretion. You will see that, without such concepts as we are developing to-day, it will be impossible for us to get any further with our study of the human organism. I should like, in order to be able gradually to carry forward our thinking to the essential nature of a process of excretion, first to submit for your consideration another concept which has, to be sure, only a remote similarity to the excretory processes, but which can nevertheless guide us to them, namely, the concept of the becoming aware of our Self.

Think for a moment, how is it really possible after all to affirm that there is such a thing as the becoming aware of one's Self? If you move incautiously in a room and stumble against some external object you say that you have run into something. This impact is actually a becoming aware of your own Self in such a way, that the collision has in reality become for you an inner occurrence. For what is the collision with a foreign object so far as it affects you? It is the cause of a hurt, a pain. The process of feeling pain takes place entirely within yourself. Thus an inner process is called forth by the fact that you come into contact with a foreign object, and that this constitutes a hindrance in your way. It is the becoming aware of this hindrance that calls forth the inner process which, in the moment of collision, makes itself known as pain. In fact, you can easily conceive that you do not need to know anything else whatever in order to experience this becoming aware of your Self except the effect, the pain, caused by coming into contact with an external object. Imagine that you stumble against an object in the dark without knowing at all what it is, and that you hit it so hard that you do not even stop to think what it might be, but notice only the effect in the pain.

In this case you have felt the blow in its effect in such a way that you live through an inner process within yourself. You are not inwardly conscious of anything but an inner process in such a case, where you think of the blow as having taken place in the dark and of your having experienced its effect in pain. Of course, you say to yourself “I have run into something,” but this is nevertheless a more or less unconscious conclusion resulting from your inner experience of the outer object.

From this you can see that man becomes aware of his inner Being in the sensing of resistance. This is the concept we must have: becoming aware, consciousness of inner life, of being filled with real inner experiences through the sensing of a resistance. This is somewhat the concept which I have here developed in order to be able to make the transition to another concept, that of the excretions in the human organism. Let us suppose that the human organism takes into itself in some way or other, into one of its organ-systems, a certain kind of physical substance, and that this organ-system is so regulated that through its own activity it eliminates something from the substance taken in, separates it from the substance as a whole, so that through the activity of this organ the original complete substance falls apart into a finer, filtered portion and a coarser portion, which is excreted. Thus there begins a differentiating of the substance taken in, into a substance that is further useful, which can be received by other organs, and another that is first separated and then excreted. The unusable portions of the physical substance are thrust away in contrast with the usable portions, an expression here justified, and we have such a collision as I described roughly in the case of one's running against some outer object. The stream of physical matter as a whole, when it comes into an organ, runs against a resistance as it were; it cannot remain as it is, it must change itself. It is told by the organ, as we might say: “You cannot remain as you are; you must transform yourself.” Let us suppose that such a substance goes into the liver. There it is told, “You must change yourself.” A resistance is set up against it. For further use it must become a different substance, and it must cast off certain portions. Thus it happens in our organism that the substance perceives that resistance is present. Such resistances are to be found within the entire organism in a great number of different organs. It is only because secretion takes place at all in our organism, because we have organs of secretion, that it is possible for our organism to be secluded within itself; to be a self-experiencing being. For only so can any being become conscious of its own inner life, through the fact that its own life meets with resistance. Thus we have in the processes of secretion processes important for human life—processes, in other words, by means of which the living organism secludes itself within itself. Man would not be a Being secluded within himself if such processes of secretion did not take place.

Let us suppose that the flow of nourishment or of oxygen that has been absorbed, were to pass through the human organism as if through a tube. The result, if no resistance were offered through the organs, would be that the human organism would not be conscious within itself of its own inner life but would experience itself; on the contrary, only as belonging to the great world as a whole. We might, to be sure, imagine also that the crudest form of this resistance were to appear in the human organism, that the substance in question might knock itself against a solid wall, and turn back again into itself. This would not, however, make any difference to the inner experience of the human organism; for whether a flow of food or of oxygen were to pass through the organism, entering at one end and passing out at the other, being reflected back on itself as through a hose, this would not make any real difference to an inner experience of the human organism. That this is so we can at once gather from the fact that, when we bring it about in our nervous system that a concept turns back into itself, we thereby lift our nervous system right out of the inner experience of the human organism. It makes no difference why the human organism is left unaffected, whether because the streams entering from without are completely reflected or merely pass through. What makes it possible to realise the inner life of the human organism is the processes of secretion.

Now if we observe that organ which we must consider the central organ of the human organism, the organ of the blood, noting how it continually renews the blood in one direction by taking in oxygen, and if we see in this organ the instrument of the human ego, we may then say that if the blood were to go through the human ego unchanged, it could not in that case be the instrument of the human ego, that which in the very highest sense enables man to be conscious of his own inner life. Only through the fact that the blood undergoes changes in its own inner life, and then goes back as something different, in other words, that something is excreted from the changed blood, only because of this is it possible for man, not only to have an ego, but to experience it inwardly with the help of a physical-sensible instrument.

We have now enunciated the concept of the process of excretion. We shall next have to ask ourselves how it is with that excretion pertaining to the outermost boundary of the human organism. It will certainly not be difficult for us to conceive that the human organism as a whole must operate in such a way that this excretion can take place just where it does, on the periphery. For this purpose it is necessary that, confronting all the streams of the human organism, there should be one organ which is connected with this most extensive of all the processes of excretion. And this organ which is, as you will readily surmise, the skin in its most comprehensive sense together with everything pertaining to it, presents most directly to the view what we call essential in the human form. When we picture to ourselves, therefore, that the human organism can be inwardly conscious of its own life at its outermost periphery only through the fact that it has placed the organ of the skin where it confronts all its various streams, we are obliged to see in the peculiar formation of the skin one of the expressions of the innermost force of the human organism.

How shall we think of the skin-organ with everything pertaining to it? We shall see later in detail what it is that pertains to it, but to-day we shall characterise these relationships as a whole.

Here we must be clear about one thing. In what belongs to our conscious inner experience, about which we can still have a kind of knowledge through some sort of self-observation, there is not to be included that structure which comes to expression in the form of our skin. Even though we are still actively sharing in the fashioning of the outer surface of our body, this active sharing is such that we may say all directly voluntary action is completely excluded. It is true that as regards the mobility of the surface of our body, in our facial expression, gestures, etc., we have an influence which still extends to what we may call our conscious activity; but in the actual formation we have no longer any influence. It must, of course, be admitted that man does have a certain influence within narrow limits upon the outer form of his body through his inner life between birth and death. With regard to this anyone can convince himself who has known a man at a certain definite time of life, and who then sees him again after perhaps ten years. Especially is this true if, during these ten years, this man has gone through profound inner experiences, and especially those connected with the acquiring of knowledge, not such knowledge as constitutes the subject-matter of external science, but rather those which cost blood and are connected with the destiny of the whole inner life. We then see, indeed, how within certain narrow limits the physiognomy changes; how to a certain extent, therefore, man does have within these limits an influence upon the formation of his body. Yet he has it only to a very slight degree, as anyone will have to admit; for the most essential share in the forming of man is not entrusted to his volition with the help of what reaches him through his consciousness. On the other hand we must admit that the entire human form is adapted to man's essential being. Anyone who looks into these things will never for a moment imagine that what we mean by the whole range of human capacities could develop in a being having any other form than the human form as it exists in the physical world. Everything in the way of human capacities is related to this human form. Just suppose for a moment that the frontal bone were in any other position with relation to the whole organism than what it is; in that case you would have to suppose that this different position of the frontal bone, this changing of form, would presuppose at the same time entirely different capacities and forces in man. It is possible, indeed, to make a study of this in mankind as one comes to see clearly that there are different capacities among human beings having a different outer formation of the head or other organs. This is the way, then, that we must create for ourselves a concept of the conformity of the human form to man's being in its totality, of the complete correspondence between the outer form and the essential quality of man's entire being. What lies in the forces that are active in this adaptation has nothing to do with what enters into man's own activity within the compass of his own consciousness. Since, however, man's form is connected with his spiritual activity, and with his soul-life as well, it would not be possible to imagine otherwise than that the forces which bring about the human form are those which come from another direction, to meet the forces that man himself develops within his form. Here within him are the forces of intelligence, of feeling, of temperament, etc. These the human being can develop only in the physical world, as conditioned by his particular form. This form must be given to him. Whatever capacities of ours need this form must receive it already prepared, if I may express it thus, from corresponding forces of a similar kind, which, working from the other direction, first build up the form in order that these capacities may be used as they ought to be used. It is not difficult to gain this concept. We need only think of a case like the following. When we have a machine which is to be used for some intelligent activity, some activity that has a purpose, we have to do in the first place with the machine and this purposeful activity. In order, however, that the machine may come into existence, it is necessary that similar activities be carried out, which assemble the parts of the machine and give form to the whole. These activities must be similar to those which are later carried on by means of the machine itself. We must say, therefore, that when we observe a machine it is wholly and absolutely explicable on mechanical principles; but the fact that the machine is adapted to its purpose requires us to suppose that it came into existence through the activity of a mind which had thought out that purpose beforehand. This spiritual activity has withdrawn, to be sure, and does not need to be brought forward when we wish to explain the machine scientifically; yet it is there, behind the machine, and first produced it.

So likewise can we say that, for the developing of our capacities and powers as human beings, we need above all those systems of forms which lie within the moulding of our organism. There must be behind this human form, however, forces that do the forming, which we can as little find in the already fashioned form as we find the builder of the machine in the machine itself.

Through this idea something else will become quite clear to you. A materialistic thinker, for instance, might come forward and say: “But why do we need to assume that there are intelligent forces and beings behind that which gives form to our physical world? We can, indeed, explain the physical world through itself, by means of its own laws: a watch or a machine, for example, can be explained by means of its own laws.” Here we have arrived at a point where the worst kind of errors appear, on this side and that, where from the anthroposophical standpoint also, or among those who stand for some other spiritual world-conception, such errors occur. If it should be disputed, for example, by a spiritual-scientific world-conception that the human organism as it presents itself to us and which we are now observing according to its form, can be explained purely mechanically, or mechanistically through its own laws, that would naturally be going too far and would be quite unjustified. The human organism is, indeed, absolutely and entirely explainable out of its own laws, just as is the watch. Yet it does not follow from the fact that the watch can be explained by means of its own laws that the inventor was not behind the watch. This objection, accordingly, answers itself through the very fact that it must be admitted that the human organism must be explained on the basis of its own laws.

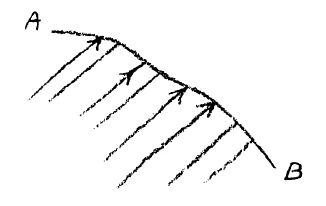

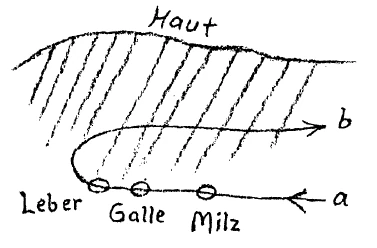

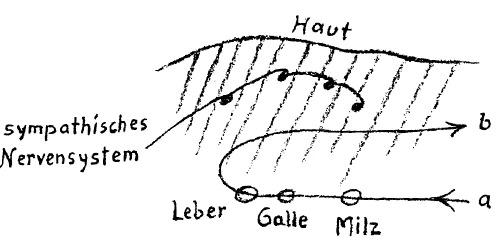

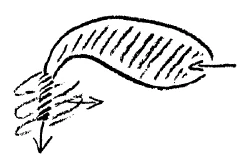

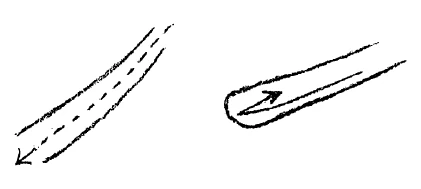

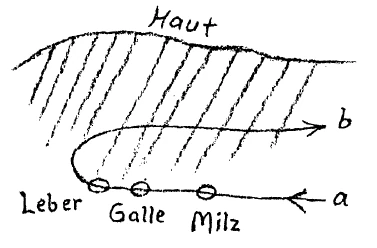

When we think, therefore, from the point of view of spiritual science, we have first to seek behind the form of a man as a whole for the form-creative beings—that is for what underlies this entire human being. If we wish to form a concept of how the human form comes to be at all, we must think of it as coming about on the one side through the fact that the form-giving forces unfold themselves, and that in the building up of this human form they at first enclose themselves within it. We have presented to us, accordingly, in the formation of the skin, the most extensive circumference spatially of that which stands for the self-enclosing of the formative forces in man. We might draw a sketch and think of of these form-giving forces in man as flowing outward and enclosing themselves within the outer form, which shall here be indicated simply by the line AB. It will becom clear to us that we shall have further need for this concept in order to understand what goes on at this outermost circumference of the human being, anywhere inside the skin. There is something else, however, about which we must be clear: that not only within the human skin do we find such enclosing, but also within the human organism itself we have the same sort of self-enclosing of the activity and fullness of being which work into it from outside. You need only reflect upon all that has been said up to this point and you will remember that we do find just such self-enclosing activity inside the human being, one in which we take no more part than in the forming of our skin-surface. We mean here those very activities which come about in the organs of the liver, the gall-bladder, the spleen, etc. That which streams into the organism by means of the forces contained in the nutritive substances is stopped by these organs. Something is pushed against it; a resistance is set up in opposition to it. In other words here in these organs the external vital activity of these substances is transformed. Whereas, therefore, in the case of the form-giving forces within us, it is necessary to think of these as being active as far as the skin, and whereas outside the skin we find no more form-giving forces, we must picture to ourselves that in the case of those forces which enter into us with the stream of nutrition or air, there is not a complete enclosing of what finds its way inward as currents from without, but rather there takes place a transformation. We must not think of these organs as stopping something, as is the case with the skin, but must rather think that the vital activity of the substances is so changed by them that the stream of food taken in by these organs (a) is then conveyed further in a changed form (b) after it has met with resistance. Thus we have here to do with a process of change, and this concerns especially those particular organs which we have characterised as the inner cosmic system in man. They change the external movements of the substances. These are forces which, in contrast to the form-forces that build up the whole organism, we may call forces of movement. Within our inner cosmic system these forces, which transform the inner vital activity of the nutritive substances, themselves become movement; so that we can rightly speak here of forces of movement in these organs.

We are now far enough advanced in our considerations to be able to say that there are forces which work from outside into the human organism, forces whose activity we cannot compass within the horizon of our consciousness. All that we can refer to as “activities” in this case takes place below the threshold of our consciousness, for certainly no one in a normal state of consciousness can observe the activity of his liver, his gall-bladder, spleen, etc. And now, since our whole nervous system is a member of our organism, the question arises: what prevents this nervous system from knowing something about the formation of the organs in this organism? This certainly does take place there; the forces that give us our form are at work in our organism, and similarly those within our inner cosmic system which change the movement and the vital activity of substances. How does it come about that we know nothing of all this?

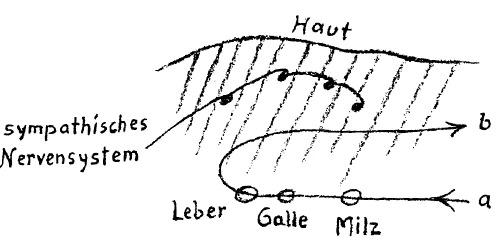

The nervous system of our brain and spinal cord is intended, in a normal state of consciousness, to convey external impressions to the blood, that is, to take the impressions in as physical processes in such a way that these processes beat against the blood, as it were, and in doing this inscribe themselves upon the instrument of the ego, the blood, so that the outer impressions are thereby transferred to it. And just as truly the branches of the sympathetic nervous system which, with its ganglions and ramifications, stands guard over the inner cosmic system, are intended to keep the processes that go on in this inner cosmic system from approaching as far as the blood, to hold these processes back, so to speak. You have now heard something more in regard to what I have previously touched upon, namely, that the sympathetic nervous system has a function contrary to that of the nervous system of the brain and spinal cord. Whereas the latter must make the effort to convey external impressions to the blood in the best possible way, the sympathetic nervous system, with its opposite activity, must be continually holding back from the blood, from the instrument of the ego, the transformed vital activities of the substances that have been taken in. If we observe the digestive process, we have there, first, the taking in of external nutritive substances; then the holding back of the vital activities peculiar to these nutritive substances, and the transformation of these by means of the inner cosmic system of man. The vital activities of these substances, accordingly, are changed into other sorts of vital activities. In order that we need not, placed as we are in the world, continually perceive inwardly what goes on in our inner organs, this entire stream of processes must be held back from the blood by means of the sympathetic nervous system, whereas that other nervous system goes to meet what is taken in from outside.

Here, then, you have the function of the sympathetic nervous system, which becomes a part of our organism for the purpose of holding our inner processes, not allowing them to penetrate to the ego-instrument, the blood. I called your attention yesterday to the fact that the outer life and the inner life of man, as they are expressed in the ether-body, present a contrast; and that this contrast between the inner life and the outer is expressed in tensions which finally come to a climax, as we saw, in those organs of the brain called the pineal gland and the pituitary body.

Now, if you put together yesterday's and to-day's discussions, you will be able to understand that everything which beats in upon us from outside, in order to stand in the closest possible contact with the circulation of the blood, strives to unite with its counterpart, with what is held back by the sympathetic nervous system. For this reason we have, in the pineal gland, the place where what has been brought to the blood by means of the nervous system of the brain and spinal cord unites with what approaches man from the other direction; and the pituitary body is there as a last outpost to prevent the approach of what has to do with the life of the inner man. There are opposite to each other, at this point in the brain, two important organs. Everything that we live through in our inner organisation remains below our consciousness; for it would, indeed, be terribly disturbing to us if we were to share consciously in our whole process of nutrition. This is kept back from our consciousness by means of the sympathetic nervous system. Only when this reciprocal relationship between the two nervous systems, as this is expressed in the state of tension between the pineal gland and the pituitary body, is not in order does something result which we may call a “glimmering through from the one side to the other,” a being disturbed on the one side by the other. This takes place when some irregularity in the activity of our digestive organs expresses itself in our consciousness in feelings of discomfort. In this case we have a raying into the consciousness, although very obscure, of the internal life of the human being, which has first been changed with the help of the inner cosmic system from the form it had in the life outside. Or in special emotions, such as anger and the like—which have a particularly strong influence on man, originating in the consciousness, we have a breaking through from the other direction into the organism. We then have one of these cases in which emotions, unusual inner disturbances of the soul, can influence in a specially harmful way the digestion, the respiratory system and also, consequently, the circulation of the blood and everything that lies below consciousness.

It is thus possible for these two sides of human nature to act reciprocally upon each other. And we are obliged to state that, as human beings, we actually stand in the world as a duality: a duality in the first place which has, in the nervous system of the brain and the spinal cord, instruments that bring external impressions to the blood, the instrument of the ego. From this whole stream of soul-life is held back, by means of the sympathetic nervous system, everything in the way of inner realisation of the life of the organs. These two streams confront each other all along the line, so to speak; but we find their special expressions in those two organs of which we spoke at the close of yesterday's lecture. From this point we will continue our considerations in the next lecture.

Fünfter Vortrag

Es wird heute meine Aufgabe sein, bevor wir in unseren Betrachtungen weiterschreiten, einige Begriffe herbeizutragen, die wir in der weiteren Folge unserer Darstellungen notwendig brauchen werden. Da wird es insbesondere wichtig sein, daß wir uns verständigen über die Bedeutung dessen, was wir im geisteswissenschaftlichen, anthroposophischen Sinne ein physisches Organ nennen oder vielmehr den physischen Ausdruck eines Organs. Denn Sie haben ja schon gesehen, daß wir zum Beispiel über die Milz so reden können, daß die physische Milz sogar materiell entfernt werden kann oder unbrauchbar werden kann, ohne daß dasjenige, was wir im anthroposophischen Sinne die «Milz» nennen, von seiner Tätigkeit ausgeschaltet wird. Es bleibt dennoch, wenn wir ein solches physisches Organ ausgeschaltet, entfernt haben, im Organismus die Tätigkeit, die innere Regsamkeit, die durch das Organ ausgeübt worden war, immer noch übrig. Daraus sehen wir — und ich bitte Sie recht sehr, sich einen solchen Begriff für das folgende anzueignen —, daß wir alles, was physisch anschaubar, was physisch wahrnehmbar ist bei einem solchen Organ, uns wegdenken können - natürlich kann man das nicht von jedem Organ sagen -, und es bleibt doch die bestimmungsgemäße Funktion des Organs; und das, was dann bleibt, was die Funktion weiter fortführt, das müssen wir zu dem Übersinnlichen des menschlichen Organismus rechnen.

Nun sprechen wir aber überhaupt, wenn wir im Sinne unserer Geisteswissenschaft von solchen Organen sprechen wie Milz, Leber, Galle, Nieren, Lungen und so weiter, indem wir diese Namen aussprechen, zunächst gar nicht von dem, was man physisch sehen kann, sondern wir bezeichnen damit die in diesen Organen wirkenden Kraftsysteme, die übersinnlicher Natur sind. Daher werden wir, und das ist in besonderem Grade bei der Milz der Fall, wenn wir geisteswissenschaftlich davon sprechen, zunächst ein äußerlich physisch nicht sichtbares Kraftsystem uns denken müssen. Denken wir also in dem, was ich hier zeichne, ein physisch nicht sichtbares Kraftsystem, das nur anschaubar werden könnte für ein übersinnliches Schauen.

Ein solches wäre also zum Beispiel in der Gegend unserer Milz nur als übersinnliches Kraftsystem sichtbar. Wenn wir nun ins Auge fassen, daß ja im wirklichen uns vorliegenden menschlichen Organismus dieses übersinnliche Kraftsystem ausgefüllt ist mit sinnlicher Materie, so müssen wir uns fragen: Wie haben wir uns nun das Verhältnis dieses übersinnlichen Kraftsystems zu dem, was sinnliche Materie ist, zu denken?

Ich glaube, es wird Ihnen nicht schwierig werden, zu denken, daß Kräfte durch den Raum gehen können, welche zunächst nicht sinnlich anschaubar sind. Man braucht sich nur an folgendes zu erinnern: Wer zum Beispiel niemals etwas von der Realität der Luft in einer von Wasser entleerten Flasche gehört hat, der wird der Meinung sein, die Flasche sei ganz leer. Ein solcher physikalisch Unkundiger wird einigermaßen erstaunt sein zu sehen, daß, wenn wir eine leere Wasserflasche auf den Tisch stellen, einen gut anschließenden enghalsigen Trichter aufsetzen und rasch Wasser in den Trichter eingießen, wir das Wasser im Trichter behalten und es nicht in die Flasche hineinfließen kann, weil es durch den Gegendruck der Luft verhindert wird, in die Flasche einzudringen. Ein solcher Mensch wird dann gewahr, daß doch ein für ihn Unsichtbares in der Flasche darinnen ist, welches das Wasser zurückhält. Denken Sie sich diesen Begriff etwas erweitert, so wird es auch nicht schwierig sein, sich vorzustellen, daß der Raum von Kraftsystemen durchdrungen sein kann, welche zunächst übersinnlicher Natur sind, so daß wir sie nicht mit dem Messer durchschneiden können und daß sie auch nicht angegriffen werden können, wenn ein physisches Organ, das ihr materieller Ausdruck ist, zum Beispiel die Milz, erkranken sollte. Wir haben uns zu denken, daß ein übersinnliches Kraftsystem zu dem, was wir als physisch-sinnliches Organ sehen, in einem solchen Verhältnis steht, daß physische Materie sich in dieses Kraftsystem einlagert, angezogen von den Kraftpunkten und Kraftlinien, und dadurch zu einem physischen Organ wird. Wir können sagen: Der Grund, warum zum Beispiel an der Stelle der Milz ein physisch-sinnliches Organ sichtbar ist, ist also der, daß dort in einer ganz bestimmten Weise Kraftsysteme den Raum ausfüllen, welche die Materie so heranziehen, daß sie sich in einer solchen Weise einlagert, wie wir es an dem äußeren Organ der Milz sehen, wenn wir es anatomisch betrachten.

So können Sie sich die verschiedensten Organe im menschlichen Organismus denken. Sie sind zuerst übersinnlich veranlagt und dann ausgefüllt unter dem Einfluß der verschiedensten übersinnlichen Kraftsysteme von physischer Materie. Daher müssen wir in diesen Kraftsystemen zunächst einen übersinnlichen Organismus sehen, der in sich differenziert ist, der in den verschiedensten Weisen die physische Materie sich eingliedert und dessen Kompliziertheit das physische, ihm eingegliederte Organ nur unvollständig zu folgen vermag. Damit haben wir nicht nur den Begriff des Verhältnisses der übersinnlichen Kraftsysteme zu den eingelagerten physisch-materiellen Organen gewonnen, sondern zugleich auch einen anderen Begriff, den der Ernährung des Gesamtorganismus. Worin besteht denn diese Ernährung des Gesamtorganismus? Sie besteht in nichts anderem als darin, daß die aufgenommenen Nahrungsstoffe so vorbereitet werden, daß es möglich ist, sie hinzuleiten nach den verschiedenen Organen, und diese sich dann die Stoffe eingliedern. Wir werden in den folgenden Vorträgen noch sehen, wie dieser allgemeine Begriff der Ernährung, der sich zeigt als eine Anziehungskraft der verschiedenen Organsysteme für die Nahrungsstoffe, sich verhält zur Entstehung des einzelnen Menschen, zur Keimesgeschichte des einzelnen Menschen, die vor der Geburt liegt. Der umfassendste Begriff der Ernährung ist also der, daß durch übersinnliche Kraftsysteme, durch einen übersinnlichen Organismus die einzelnen Nahrungsstoffe eingesogen und in der verschiedensten Weise dem physischen Organismus eingegliedert werden.

Nun müssen wir uns klar sein, daß der Ätherleib des Menschen, der das nächste übersinnliche Glied in der menschlichen Organisation ist nach dem physischen Leibe, daß dieser Ätherleib, wenn er auch das gröbste der übersinnlichen Glieder ist, wie ein übersinnliches Urbild dem gesamten Organismus zugrundeliegt, daß er in sich gegliedert, differenziert ist und die mannigfaltigsten Kraftsysteme enthält, um sich die durch die Ernährung aufgenommenen Stoffe einzugliedern. Wir haben nun aber nach diesem ätherischen Leib, den wir als das Urbild des menschlichen Organismus betrachten können, als das nächsthöhere Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit den sogenannten Astralleib. Wie sich diese beiden zusammenschließen, werden uns die nächsten Vorträge noch zeigen. Der Astralleib ist das, was sich erst eingliedern kann, wenn sowohl der physische Organismus als auch der ätherische Organismus ihrer Anlage nach schon vorbereitet sind; er setzt die beiden anderen Organismen voraus. Ferner haben wir das, was wir das menschliche Ich nennen, so daß die gesamte menschliche Wesenheit sich zusammenschließt aus diesen vier Gliedern. Wir können uns nun vorstellen, daß schon im Ätherleib selbst gewisse Kraftsysteme sind, die die Nahrungsstoffe an sich ziehen und sie dann im physischen Organismus in einer ganz bestimmten Weise gestalten. Wir können uns aber auch vorstellen, daß ein solches Kraftsystem nicht nur durch den Ätherleib bestimmt ist, sondern auch durch den Astralleib und daß dieser seine Kräfte da hineinsendet, so daß, wenn wir uns das physische Organ wegdenken, wir zunächst das ätherische Kraftsystem haben würden, dann das astralische Kraftsystem, welches das ätherische Kraftsystem in einer ganz bestimmten Weise durchdringt, und wir können uns vorstellen, daß da auch noch Strahlungen vom Ich hineindringen.

Es kann nun Organe geben, welche so in den Organismus eingegliedert sind, daß ihr Wesentlichstes darauf beruht, daß die ätherischen Strömungen in ihrer Eigenart noch sehr wenig bestimmend gewirkt haben, so daß, wenn wir den Raum okkult untersuchen, in dem ein betreffendes Organ sich befindet, wir finden würden, daß der ätherische Teil dieses Organs recht wenig durch sich selber differenziert ist, nur wenig von diesen Kraftsystemen enthält, daß aber dafür dieser Teil des Ätherleibes durch starke astralische Kräfte beeinflußt wird. Dann wird, wenn die physische Materie sich einem solchen Organ eingliedert, der Ätherleib nur eine geringe Anziehungskraft auf die einzugliedernden Stoffe ausüben, die hauptsächlichste Anziehungskraft wird dann vom Astralleib auf das betreffende Organ ausgeübt, und zwar so, als ob die betreffenden Stoffe direkt von dem Astralleibe hereingeholt würden in das betreffende Organ. Daraus sehen Sie, daß die Organe des Menschen von ganz verschiedener Wertigkeit sind. Es gibt solche Organe, von denen man sagen muß, daß sie hauptsächlich bestimmt sind durch Kraftsysteme des Ätherleibes, andere, die mehr bestimmt sind durch Strömungen oder Kräfte des Astralleibes, während noch andere mehr bestimmt sind durch Strömungen des Ich. Aus den Ausführungen, die in den Vorträgen gemacht worden sind, können Sie sich schon sagen, daß insbesondere das Organsystem, das unser Blut führt, im wesentlichen von solchen Strahlungen abhängt, die von unserem Ich ausgehen, daß also das menschliche Blut im wesentlichen mit Strömungen und Strahlungen des menschlichen Ich zusammenhängt. Die anderen Organsysteme und ihre Inhalte sind in den verschiedensten Abstufungen von den übersinnlichen Gliedern der menschlichen Natur bestimmt.

Aber es kann auch der umgekehrte Fall eintreten, wenn wir nämlich den physischen Leib an sich nehmen, der ja - jetzt abgesehen von seinen höheren Gliedern — auch ein Kraftsystem darstellt. Er stellt zunächst das dar, was man sich zusammengesetzt denken kann aus Stoffen der äußeren Welt, die auch ihre inneren Gesetze haben, die aber umgewandelt dem physischen Leibe eingefügt sind. Der physische Leib ist also auch ein Kraftsystem. So daß Sie sich auch den Fall denken können, daß der physische Organismus wieder zurückwirkt auf das ätherische oder bis auf das astralische Kraftsystem oder sogar bis ins Ich-System hinein. Wir müssen uns denken, daß das ätherische Kraftsystem nicht nur eingefangen wird von dem astralischen oder vom Ich-System, sondern daß es auch Organe gibt, bei denen die ätherischen Kräfte von der Seite des physischen Kraftsystems derart eingespannt werden, daß das physische Kraftsystem überwiegt. Solche Organe, bei denen der physische Leib das Überwiegende ist, die also nur in geringerem Maße beeinflußt werden von den höheren Gliedern der menschlichen Organisation, das sind hauptsächlich diejenigen Organe, welche im weitesten Sinne als Absonderungsorgane zu bezeichnen sind, alle drüsigen Organe, alle Absonderungsorgane überhaupt. Alle Absonderungsorgane, alle Organe, welche direkt Stoffe absondern, werden zu diesen Stoffabsonderungen — also zu einem Vorgang, der innerhalb der rein physischen Welt seine wesentliche Bedeutung hat — hauptsächlich durch die Kräfte des physischen Organismus veranlaßt. Wo immer im menschlichen Organismus solche Organe sind, wenn sie vorzugsweise zum Absondern des Stofflichen bestimmt sind, müssen wir uns klar sein, daß solche Organe, die hauptsächlich Werkzeuge der physischen Kraftsysteme sind, durch Erkrankung, durch Unbrauchbarwerden oder durch ihre Entfernung den Organismus unfehlbar zum Verfall bringen, so daß er dann nicht mehr in entsprechender Weise sich entwikkeln und zuletzt nicht mehr leben kann. Sie sehen an einem solchen Organ, wie es die Milz ist, von der wir gestern gesprochen haben, daß deren Erkranken, deren sonstiges Unbrauchbarwerden oder operative Entfernung den physischen Körper in seinen Funktionen weit weniger stört, als dies bei anderen Organen der Fall ist, weil sie in besonders starker Weise beeinflußt wird von den übersinnlichen Teilen der menschlichen Natur, vom Ätherleibe, namentlich aber vom Astralleibe. Anders ist es bei den Organen, wo das physische Kraftsystem überwiegt. Eine Erkrankung der Schilddrüse zum Beispiel, die sich bei bestimmten Erkrankungen manchmal vergrößert zur sogenannten Kropfbildung, kann auf den ganzen Organismus sehr schädlich wirken. Sie darf aber nicht vollständig unbrauchbar werden oder vollständig entfernt werden, und zwar deshalb nicht, weil sie ihre Wirkungen so zu äußern hat, daß das, was als physischer Vorgang durch sie bewirkt wird, im Gesamthaushalt des menschlichen Organismus ganz wesentlich ist.

Nun kann es solche Organe geben, die in hohem Maße abhängen von den übersinnlichen Kraftsystemen der menschlichen Organisation, die aber doch eingespannt sind in den physischen Organismus und durch dessen Kräfte veranlaßt werden, Stoffliches abzusondern. Ein solches Organ ist zum Beispiel die Leber, ebenso sind es die Nieren. Das sind Organe, die, geradeso wie die Milz, abhängig sind von den übersinnlichen Gliedern der menschlichen Organisation, vom Ätherleibe und Astralleibe, die aber sozusagen eingefangen sind von den Kräften des physischen Organismus, heruntergezogen sind in ihren Wirkungen bis zu den Kräften des Physischen. Daher kommt es bei ihnen in einem viel höheren Grade darauf an, daß sie als physische Organe in gesundem Zustande sind, als zum Beispiel bei der Milz, bei welcher die Sache so liegt, daß das Physische sehr wenig in Betracht kommt und weit überwogen wird von dem, was von den übersinnlichen Gliedern der menschlichen Organisation herkommt. Wir können von der Milz sagen, daß sie ein sehr geistiges Organ ist, denn der physische Teil dieses Organs macht den geringsten Teil seiner Bedeutung aus. Aus diesem Grunde wurde die Milz zu allen Zeiten in der okkulten Literatur, die entsprungen ist aus Kreisen, wo man wirklich etwas über diese Sachen gewußt hat, immer als ein besonders geistiges Organ angesehen und geschildert.

So also haben wir jetzt gewissermaßen den Begriff des Gesamtorganismus gewonnen, dessen einzelnes Organ angesehen werden kann als ein übersinnliches Kraftsystem, in das gleichsam die stoffliche Materie durch den gesamten Ernährungsprozeß hineingelagert wird. Ein anderer Begriff, den wir uns aneignen müssen, ist der: Was bedeutet überhaupt für den Menschen die Aufnahme - sei es eines Stoffes oder sei es die Aufnahme eines Geistigen, die durch unsere Seelentätigkeit bewirkt wird, zum Beispiel bei der Wahrnehmung? Und was bedeutet die Absonderung, die Abgabe eines Stoffes?

Gehen wir da zunächst aus von dem Absonderungsprozeß im weitesten Umfange. Wir wissen ja, daß von den aufgenommenen Nahrungsmitteln schon ein großer Teil des Stofflichen vom Verdauungskanal abgesondert wird. Wir wissen ferner, daß durch die Lungen aus dem menschlichen Organismus die Kohlensäure ausgeschieden wird. Dann haben wir einen Absonderungsprozeß durch die Nieren, ein weiterer Absonderungsprozeß geschieht durch die Haut. In diesem letzteren, der zunächst in der Schweißbildung verläuft, aber auch in allem, was im umfänglichen Sinne als Absonderungsprozeß durch die Haut zu gelten hat, haben wir jene Absonderung zu sehen — und ich bitte, darauf zu achten -, die beim Menschen an dem äußersten Umfange, an der äußersten Peripherie seines Leibes erfolgt. Nun fragen wir uns zunächst einmal: Was bedeutet denn überhaupt ein Absonderungsprozeß für den Menschen?

Wir werden uns die Bedeutung eines Absonderungsprozesses nur klarmachen können auf folgende Weise. Sie werden sehen, daß wir ohne die Begriffe, die wir heute entwickelt haben, überhaupt nicht weiterkommen können in der Betrachtung des menschlichen Organismus. Ich möchte Ihnen, um unsere Gedanken allmählich hinüberzuführen zu der wesentlichen Natur eines Absonderungsprozesses, zunächst einen anderen Begriff vorführen, der allerdings nur eine entfernte Ähnlichkeit mit dem Absonderungsprozesse hat, der uns aber dazu hinüberführen kann, nämlich den Begriff des Gewahrwerdens unseres Selbst. Bedenken Sie einmal, wie Sie im Grunde genommen doch sagen können, daß es eine Art Gewahrwerden Ihres Selbstes ist, wenn Sie in einem Raume gehen und sich unvorsichtigerweise an einem harten Gegenstande stoßen. Dieses Anstoßen ist im Grunde genommen ein Gewahrwerden des eigenen Selbstes. Es ist ein Gewahrwerden des eigenen Selbstes auf die Art, daß Ihnen das Freignis, das sich durch den Stoß vollzogen hat, zu einem inneren Ereignis geworden ist. Denn was ist für Sie der Zusammenstoß mit einem fremden Gegenstande? Er ist die Ursache eines Wehetuns, eines Schmerzes. Der Schmerzvorgang spielt sich rein in Ihrem Inneren ab. Also ein innerer Vorgang wird dadurch hervorgerufen, daß Sie sich in Berührung bringen mit einem fremden Gegenstand, der Ihnen als Hindernis im Weg liegt. Das Gewahrwerden dieses Hindernisses ist das, was den inneren Prozeß hervorruft, der als Schmerz beim Sichstoßen auftritt. Im Grunde genommen können Sie sich leicht vorstellen, daß Sie überhaupt nichts anderes zu wissen brauchen, um das Gewahrwerden Ihres eigenen Selbstes zu erleben, als den inneren Schmerz, der durch das Anstoßen an einen äußeren Gegenstand bewirkt wird. Denken Sie sich, daß Sie im Finstern an einen Gegenstand stoßen, von dem Sie gar nicht wissen, was er ist, und nehmen Sie an, Sie stoßen sich so stark, daß Sie auch gar nicht darauf schließen können, wie der Gegenstand beschaffen sein könnte, sondern Sie spüren nur die Wirkung des Stoßes als Schmerz. Sie haben den Stoß in seiner Wirkung so empfunden, daß Sie den Vorgang in sich selbst erlebten. Sie erleben gar nichts anderes als einen inneren Vorgang, und das ist das Wesentliche. Wenn Sie allerdings auch sagen: Ich habe mich an einem äußeren Gegenstand gestoßen -, so ist das mehr oder weniger ein unbewußter Schluß von einem inneren Erlebnis auf ein äußeres Hindernis.

Daraus können Sie sehen, daß der Mensch seines Inneren gewahr wird durch das Finden eines Widerstandes. Diesen Begriff müssen wir haben: das Gewahrwerden des Selbstes, das Erleben des Inneren, das Ausgefülltsein mit realen Erlebnissen im Inneren durch das Finden eines Widerstandes. Dies ist ein Begriff, den ich, ich möchte sagen, in aller Grobheit entwickelt habe, um von ihm den Übergang machen zu können zu einem anderen Begriffe, dem der Absonderungen im menschlichen Organismus. Denken wir uns einmal, der menschliche Organismus nehme in sich selber in irgendein Organsystem, meinetwegen in den Magen, eine gewisse Stofflichkeit auf und das Organsystem sei so eingerichtet, daß es durch seine Tätigkeit aus diesem Stoffe, der da aufgenommen ist, etwas aussondert, etwas gleichsam separiert, wegnimmt von dem Gesamtstoff, so daß durch diese Tätigkeit des Organs der Gesamtstoff zerfällt in einen feineren, gleichsam filtrierten Teil und in einen gröberen Teil, der ausgesondert wird. Es wird also eine Differenzierung des Stoffes vorgenommen in einen solchen, der in einen weiter brauchbaren, für andere Organe aufzunehmenden Stoff umgewandelt wird und in einen solchen, der erst abgesondert und dann ausgeschieden wird.

Hier an dieser Stelle, wo die unbrauchbaren Teile der Stofflichkeit abgestoßen werden gegenüber den brauchbaren Stoffen, hier haben Sie in modifizierter Form etwas wie ein Sichanstoßen an einen äußeren Gegenstand, wie ich es eben dargestellt habe. Es stößt der aufgenommene Stoffstrom, indem er an ein Organ herankommt, sozusagen auf einen Widerstand; er kann nicht so bleiben, wie er ist, er muß sich ändern. Es wird ihm gleichsam durch das Organ gesagt: So kannst du nicht bleiben, wie du bist, du mußt dich ändern. — Es wird also dem Stoff ein Widerstand entgegengestellt, er muß als ein anderer Stoff weiterverbraucht werden, und er muß gewisse Teile abstoßen. In unserem Innern stellt sich das Organ dem Stofflauf so entgegen, wie sich der äußere Gegenstand uns entgegenstellt, an dem wir uns stoßen. Solche Widerstände finden sich innerhalb des Gesamtorganismus in den mannigfachsten Organen. Und erst dadurch, daß überhaupt in unserem Organismus abgesondert wird, erst dadurch, daß wir Absonderungsorgane haben, dadurch ist die Möglichkeit gegeben, daß unser Organismus eine in sich abgeschlossene, sich selbst erlebende Wesenheit ist. Denn Erleben kann sich eine Wesenheit nur dadurch, daß sie auf Widerstand stößt. So haben wir in den Absonderungsprozessen wichtige Prozesse des menschlichen Lebens, nämlich diejenigen Prozesse, wodurch sich der lebendige Organismus in sich selber abschließt. Der Mensch wäre kein in sich abgeschlossenes Wesen, wenn solche Absonderungsprozesse nicht vorhanden wären.

Denken Sie sich einmal, der aufgenommene Nahrungsstrom oder der Sauerstoffstrrom würden durch den menschlichen Organismus wie durch einen Schlauch glatt hindurchgehen und es gäbe keinen Widerstand durch die Organe. Die Folge davon wäre,, daß der menschliche Organismus sich nicht in sich selbst erleben könnte, sondern er würde sich nur erleben als angehörig der gesamten großen Welt. Wir könnten uns ja allerdings auch vorstellen, daß innerhalb des menschlichen Organismus die gröbste Art dieses Widerstandbietens eintreten würde, daß der Stoffstrom sich an einer festen Wandung stoßen und reflektieren, zurückkehren würde. Das würde aber das innere Erleben des menschlichen Organismus nicht berühren, denn ob der Nahrungsstrom oder der Sauerstoffstrom durch den menschlichen Organismus wie durch einen Schlauch hindurchginge, auf der einen Seite hinein, auf der anderen wieder hinaus, oder ob er reflektiert würde, das würde für das innere Erleben nichts ausmachen. Daß das so ist, können Sie schon daraus entnehmen, daß — wie wir schon gesagt haben -, wenn wir es in unserem Nervensystem dazu bringen, daß eine Vorstellung in sich selbst zurückkehrt, wir dann geradezu unser Nervensystem herausheben aus dem Erleben des inneren Organismus. Es macht also keinen Unterschied, ob völlige Reflexion oder bloßes Hindurchgleiten der von außen hineingehenden Ströme durch den menschlichen Organismus vorliegt. Was den menschlichen Organismus in sich selbst erlebbar macht, das sind die Absonderungen.

Wenn Sie dasjenige Organ betrachten, welches wir als das Mittelpunktsorgan für den menschlichen Organismus ansehen müssen, das Blutsystem, wenn Sie sehen, wie auf der einen Seite das Blut immerfort durch Aufnehmen von Sauerstoff sich auffrischt, und wenn Sie auf der anderen Seite das Blutsystem als das Werkzeug des menschlichen Ich betrachten, so können wir sagen: Wenn das Blut unverändert durch den menschlichen Organismus hindurchgehen würde, so könnte es nicht das Organ des menschlichen Ich sein, das im eminentesten Sinne das Organ ist, welches den Menschen sich innerlich erlebbar macht. Nur dadurch, daß das Blut in sich selber Veränderungen durchmacht und als ein anderes wieder zurückkehrt, daß also Absonderungen geschehen von verändertem Blut, nur dadurch ist es möglich, daß der Mensch das Ich nicht nur hat, sondern es auch erleben kann mit Hilfe seines sinnlich-physischen Werkzeuges, des Blutes.

Daraus hat sich uns nun dieser Begriff der Absonderung ergeben. Und jetzt werden wir uns zu fragen haben: Wie steht es nun mit jener Absonderung, welche wir vorhin bezeichnet haben als der äußersten Peripherie des menschlichen Organismus angehörig? — Es wird uns ja unschwer sein, uns vorzustellen, wie der Gesamtorganismus des Menschen wirken muß, damit diese Absonderung an der Peripherie geschehen kann. Dazu ist es notwendig, daß den gesamten Strömungen des menschlichen Organismus entgegengestellt werde ein Organ, welches in Zusammenhang steht gerade mit diesem umfänglichsten Absonderungsprozeß. Und dieses Organ, das ja, wie Sie sich leicht denken können, die Haut ist, mit allem, was zu ihr gehört im umfänglichsten Sinne, das ist zugleich dasjenige, was schon für den unmittelbaren äußeren Anblick als das Wesentliche der menschlichen Gestalt, der menschlichen Form sich darbietet. Wenn wir uns also vorstellen, daß der menschliche Organismus, der sich selbst erleben kann an seinem äußeren Umfange, dies nur dadurch kann, daß er das Organ der Haut seinen gesamten Strömungen entgegenstellt, so müssen wir in der eigenartigen Formung der Haut einen der Ausdrücke sehen für die innersten Kräfte des menschlichen Organismus.

Wir werden uns nun zu fragen haben: Wie haben wir uns denn dieses Hautorgan zu denken? Wie haben wir uns die Haut mit allem, was dazugehört, zu denken? Wir werden schon sehen, was im einzelnen dazugehört, wir wollen es aber heute nur im großen und ganzen charakterisieren. Da müssen wir uns zunächst darüber klar sein, daß in dem, was zu unserem bewußten Erleben gehört, wovon wir eine Erkenntnis haben können durch irgendeine Selbstbeobachtung, jene Gestaltung nicht einbegriffen ist, welche in der Formung unserer Haut zum Ausdruck kommt. Selbst wenn wir in begrenztem Umfange mittätig sind an der Gestaltung unserer äußeren Körperoberfläche, so ist sie doch etwas, das sich der unmittelbaren Willkür in vollkommenster Weise entzieht. Nur in bezug auf die Beweglichkeit unserer Haut, in bezug auf Mienenspiel, Gesten und so weiter, haben wir ja einen Einfluß, der noch an das heranreicht, was wir bewußte Tätigkeit nennen können; aber auf die Gestalt, auf die Form unserer Körperoberfläche haben wir keinen Einfluß mehr. Es muß freilich zugegeben werden, daß der Mensch zwischen Geburt und Tod einen gewissen Einfluß auf seine äußere Leibesform in engeren Grenzen hat. Davon kann sich jeder überzeugen, der einen Menschen kennengelernt hat in einem bestimmten Lebensalter und ihn vielleicht nach zehn oder zwanzig Jahren wiedersieht, insbesondere wenn dieser Mensch in diesen Jahren durchgegangen ist durch tiefere innere Erlebnisse, namentlich durch Erkenntniserlebnisse, die nicht Gegenstand der äußeren Wissenschaft sind, sondern durch solche, die «Blut kosten», die zusammenhängen mit unserem ganzen Lebensschicksal. Dann sehen wir allerdings innerhalb enger Grenzen, wie die Physiognomie sich ändert, wie also der Mensch innerhalb dieser Grenzen einen Finfluß hat auf die Gestaltung seines Leibes. Aber er hat ihn nur in geringem Maße, und das wird jeder zugeben müssen; denn das Hauptsächlichste in der menschlichen Gestalt ist durchaus nicht in unsere Willkür gegeben und nicht durch unser Bewußtsein bestimmt. Dennoch müssen wir sagen: Die ganze menschliche Gestalt ist angepaßt der menschlichen Wesenheit; und wer auf die Dinge eingeht, wird sich niemals vorstellen können, daß dasjenige, was wir den ganzen Umfang der menschlichen Fähigkeiten nennen, sich entwickeln könnte in einem Wesen von einer anderen Gestalt, als es die heutige Menschengestalt ist. Alles, was an Fähigkeiten im Menschen ist, hängt zusammen mit dieser Menschengestalt. Denken Sie sich nur einmal, daß erwa das Stirnbein in einer irgendwie anderen Lage wäre zu dem Gesamtorganismus, als es ist, so würde diese Gestaltänderung ganz andere Fähigkeiten und Kräfte im Menschen voraussetzen. Darüber könnten ja Studien gemacht werden, indem man sich klarmacht, wie andere Fähigkeiten vorhanden wären bei Menschen mit verschiedener äußerer Gestaltung des Kopfes, des Schädelbaus und so weiter. So müssen wir uns einen Begriff verschaffen von dem Angepaßtsein der menschlichen Gestalt an die gesamte innere menschliche Wesenheit, ja, von einem völligen Sichentsprechen der äußeren Gestalt und der inneren Wesenheit des Menschen. Was in den Kräften dieser Anpassung liegt, hat nichts zu tun mit dem, was in die eigene, vom Bewußtsein umspannte Tätigkeit des Menschen hereingehört. Da aber die Gestalt des Menschen zusammenhängt mit seiner geistigen Betätigung und auch mit seinem seelischen Leben, so können Sie es sich leicht vorstellen, daß in den Kräften, welche die physische Gestalt des Menschen zustande bringen, solche Kräfte liegen, die gleichsam von einer anderen Seite entgegenkommen denjenigen Kräften, die der Mensch in sich selbst entwickelt. Kräfte der Intelligenz, Gefühlskräfte, Gemütskräfte und so weiter, die kann der Mensch nur entwickeln in der physischen Welt unter der Voraussetzung seiner besonderen Gestalt. Diese Gestalt muß ihm gegeben sein. Er muß also diese Gestalt für seine Fähigkeiten zubereitet erhalten — wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf von Kräften entsprechend ähnlicher Art wie die, die von der anderen Seite her diese Gestalt erst aufbauen, damit sie dann zu dem gebraucht werden kann, wozu sie verwendet werden soll. Es ist unschwer, sich diesen Begriff zu verschaffen, denn man braucht nur daran zu denken, daß eine Maschine, die wir zu einer Tätigkeit verwenden wollen, für diese Tätigkeit intelligent und zweckmäßig eingerichtet sein muß. Damit eine solche Maschine zustande komme, ist es notwendig, daß zuerst ähnliche Verrichtungen vollführt werden, wie sie dann von der Maschine ausgeführt werden sollen, und danach die Teile der Maschine herzustellen und zusammenzugliedern, welche der Maschine ihre Form geben. Wenn wir eine fertige Maschine vor uns haben, so ist sie für uns ganz mechanisch erklärbar, wenn wir ihre Wirksamkeit sehen und verstehen. Als denkende Beobachter werden wir uns aber fragen: Wer ist es, der sie gebaut hat? — Denn ihre Zusammensetzung weist auf eine zielbewußte geistige Tätigkeit hin, welche diese Maschine zu einem bestimmten Zwecke hergestellt hat. Diese geistige Tätigkeit braucht nicht mehr da zu sein, wenn wir die Maschine mechanisch erklären wollen, aber sie steht hinter der Maschine, sie hat sie erst zustande gebracht.

Ebenso können wir sagen: Alles, was an Formsystemen in der Gestaltung unseres Organismus liegt, das ist uns in erster Linie gegeben, damit wir unsere Fähigkeiten und Kräfte als Menschen entwickeln. Aber es muß hinter dieser Gestaltung des Menschen gestaltunggebende, formgebende Kräfte geben, die wir ebensowenig in der fertigen Gestalt finden, wie wir in der Maschine den Maschiinenbauer finden.

Mit dieser Idee wird Ihnen zugleich etwas anderes völlig einleuchtend sein. Ein materialistischer Denker könnte sagen: Wozu braucht man intelligente Kräfte und bewußt schaffende Wesenheiten anzunehmen hinter unserer physischen Welt? Wir können ja die physische Welt aus sich selbst, aus ihren eigenen Gesetzen erklären. Eine Uhr, eine Maschine kann aus ihren eigenen Gesetzen heraus erklärt werden. — Hier stehen wir an einem Punkte, wo hüben und drüben die schlimmsten Fehler gemacht werden, sowohl bei solchen, die auf dem Boden einer spirituellen Weltanschauung stehen, wie auch auf der Seite der Materialisten. Wenn zum Beispiel von einer geisteswissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung bestritten würde, daß der menschliche Organismus, wie er seiner Form nach vorliegt, nicht rein mechanisch oder mechanistisch durch seine eigenen Gesetze erklärbar wäre, so würde das selbstverständlich zu weit gehen und ganz unberechtigt sein. Der menschliche Organismus ist ganz und gar aus seinen eigenen Gesetzen heraus erklärbar, wie die Uhr auch. Aber daraus, daß die Uhr aus ihren eigenen Gesetzen erklärbar ist, folgt nicht, daß hinter der Uhr nicht der Erfinder der Uhr stand, der Uhrmacher und seine geistige Tätigkeit. Dieser Einwand, der von materialistischer Seite aus gemacht werden kann, erledigt sich dadurch. Aber der Geistesforscher muß auch zugeben, daß der menschliche Organismus, so wie er vor uns steht, aus seinen eigenen Gesetzen erklärt werden kann. Aber wenn wir wirklich geisteswissenschaftlich denken, haben wir hinter der Gesamtgestaltung des menschlichen Organismus zu suchen die gestaltenden Wesenheiten, dasjenige also, was der gesamten Form der menschlichen Wesenheit zugrundeliegt. Wenn wir uns nun einen Begriff davon bilden wollen, wie überhaupt die menschliche Form zustande kommt, so müssen wir uns denken, daß sie auf der einen Seite dadurch bewirkt wird, daß die formgebenden Kräfte sich entfalten und daß sie den Menschen dadurch aufbauen, daß sie sich an den Grenzen der menschlichen Form selbst abschließen. Wir haben in der Hautbildung das am reinsten gegeben, was das räumliche Sichabschließen der formgebenden Kräfte im Menschen bedeutet. Wenn wir das schematisch zeichnen, können wir uns denken, daß die formgebenden Kräfte zur Peripherie dahinfließen und sich da abschließen in der äußeren Form, die in der Linie A-B nur angedeutet werden soll.

Wir werden nun sehen, wie wir diesen Begriff wiederum brauchen, um alles das erkennen zu können, was innerhalb der Haut geschieht. Weiter aber werden wir uns darüber klar werden müssen, daß wir nun nicht bloß in der menschlichen Haut solche Abschlüsse vor uns haben, sondern daß wir auch innerhalb des menschlichen Organismus selber solches Abschließen der von außen wirkenden Tätigkeit und Wesenhaftigkeit finden. Sie brauchen sich nur zu überlegen, was bisher gesagt worden ist, dann werden Sie darauf kommen, daß wir auch im Inneren des Menschen solche sich abschließenden Tätigkeiten vor uns haben, an denen wir ebenso unbeteiligt sind wie an unserer Oberflächengestaltung, und das sind gerade diejenigen Betätigungen, die zustande kommen in den Organen Leber, Galle, Milz und so weiter. Da wird das aufgehalten, was durch die Kräfte, die in den Nahrungsmitteln sitzen, in den Organismus einströmt, dem wird etwas entgegengeschoben, wird ein Widerstand entgegengesetzt, das heißt, es wird in diesen Organen die äußere, die eigene Regsamkeit der Stoffe umgeändert. Während also bei den formgebenden Kräften die Sache so ist, daß wir uns diese formenden Kräfte wirksam zu denken haben bis zur Haut hin und außerhalb der Haut nichts mehr von formgebenden Kräften haben, müssen wir uns vorstellen, daß bei denjenigen Kräften, die mit dem Nahrungs- oder Luftstrom nach unserem Inneren gehen, nicht ein vollständiges Abschließen dessen vorhanden ist, was als Strömungen von außen eindringt, sondern es tritt da eine Umgestaltung ein. Diese Organe müssen wir uns so denken, daß sie nicht, wie es bei der Haut ist, sich abschließen, so daß außerhalb nichts mehr ist, sondern so, daß die Regsamkeit der Stoffe umgeändert wird durch sie derart, daß der Nahrungsstrom, der von der Seite dieser Organe her aufgenommen ist (siehe Zeichnung, a), in einer anderen Weise weitergeleitet wird (b), nachdem ihm ein Widerstand entgegengesetzt worden ist. Hier haben wir es also mit einer Umänderung zu tun, und das betrifft vor allem diejenigen Organe, welche wir als ein inneres Weltsystem- des Menschen bezeichnet haben. Die ändern die äußere Regsamkeit der Stoffe um. Es sind Kräfte, die wir im Gegensatz zu den Formkräften, die den gesamten Organismus bilden, Bewegungskräfte nennen können. In unserem inneren Weltsystem werden diese Kräfte, welche die innere Regsamkeit der Nahrungsstoffe umgestalten, dann Bewegung, so daß wir hier von Bewegungskräften in den Organen sprechen können.

Wir sind jetzt so weit vorgeschritten in den Betrachtungen des menschlichen Organismus, daß wir sagen können: In den menschlichen Organismus wirken von außen Kräfte herein, deren Tätigkeit wir mit unserem Bewußtsein nicht wahrnehmen. Das alles geht unterhalb unseres Bewußtseinshorizontes vor sich, was wir da als Tätigkeit ausführen; niemand kann im normalen Bewußtsein die Tätigkeit seiner Leber, Galle, Milz und so weiter beobachten. Nun entsteht die Frage: Wodurch werden wir denn verhindert, etwas zu wissen von den Form- und Bewegungskräften, die sich in unseren inneren Organen abspielen, da doch unser Seelenleben dem Organismus eingegliedert ist? Da gehen ja in unserem Innern gewaltige Tätigkeiten vor sich. Woher kommt es, daß wir davon nichts wissen?

Nun, genau ebenso wie unser Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem dazu bestimmt ist, die äußeren Eindrücke, die wir durch unsere Sinne erhalten, bis zum Blute hinzuleiten, das heißt, die Impressionen von äußeren Vorgängen in unser Blut, in das Werkzeug des Ich, aufzunehmen, ebenso wie also das Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem dazu bestimmt ist, im normalen Bewußtsein dem Ich zu dienen, gerade so ist das sympathische Nervensystem, das sich mit seinen Knoten und Verzweigungen dem inneren Weltsystem gleichsam vorlagert, dazu ausersehen, die Vorgänge, die sich im Innern des Organismus abspielen, nicht an das Blut, das Werkzeug des Ich, heranzulassen, sondern sie vom Blut zurückzuhalten.

So sehen Sie, daß das sympathische Nervensystem eine entgegengesetzte Aufgabe hat wie das Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem, und hier haben wir eine Erklärung für den Unterschied in Bau und Beschaffenheit dieser beiden Systeme. Während das Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem sich anstrengen muß, um möglichst gut die äußeren Eindrücke zum Blut überzuleiten, muß durch das entgegengesetzt wirkende sympathische Nervensystem vom Blut — als dem Werkzeug des Ich - fortwährend zurückgestaut werden die Eigenregsamkeit der aufgenommenen Stoffe. Wenn wir den Verdauungsprozeß betrachten, so haben wir zuerst das Aufnehmen der äußeren Nahrungsstoffe, dann das Zurückstauen der Eigenregsamkeit der Nahrungsstoffe und dann die Umwandlung dieser Regsamkeiten durch das innere Weltsystem des Menschen. Damit wir nicht fortwährend, wie wir so dastehen in der Welt, alles das wahrnehmen, was in unseren inneren Organen bewirkt wird, muß der ganze Strom der Vorgänge durch das sympathische Nervensystem zurückgestaut werden vom Blut, geradeso wie durch das Gehirn-Rückenmark-Nervensystem das zum Blute hingetragen wird, was von außen aufgenommen wird. Da haben Sie die Aufgabe des sympathischen Nervensystems, unsere inneren Vorgänge in uns zu halten, sie nicht bis zum Blut, dem Werkzeug des Ich, hinaufdringen zu lassen, um das Eintreten dieser inneren Vorgänge in das Ichbewußtsein zu verhindern.

Ich habe schon gestern darauf hingewiesen, daß das Außenleben und das Innenleben des Menschen, wie es sich im Ätherleibe auslebt, in einem Gegensatz zueinander stehen und daß dieser Gegensatz von Außenleben und Innenleben in Spannungen zum Ausdruck kommt, die, wie wir gesehen haben, am stärksten werden in den Organen des Gehirnes, die wir als Zirbeldrüse und Gehirnanhang bezeichnen.