Human and Cosmic Thought

GA 151

20 January 1914, Dornach

Lecture I

In these four lectures which I am giving in the course of our General Meeting, I should like to speak from a particular standpoint about the connection between Man and the Cosmos. I will first indicate what this standpoint is.

Man experiences within himself what we may call thought, and in thought he can feel himself directly active, able to exercise his activity. When we observe anything external, e.g. a rose or a stone, and picture it to ourselves, someone may rightly say: “You can never know how much of the stone or the rose you have really got hold of when you imagine it. You see the rose, its external red colour, its form, and how it is divided into single petals; you see the stone with its colour, with its several corners, but you must always say to yourself that hidden within it there may be something else which does not appear to you externally. You do not know how much of the rose or of the stone your mental picture of it embraces.”

But when someone has a thought, then it is he himself who makes the thought. One might say that he is within every fiber of his thought, a complete participator in its activity. He knows: “Everything that is in the thought I have thought into it, and what I have not thought into it cannot be within it. I survey the thought. Nobody can say, when I set a thought before my mind, that there may still be something more in the thought, as there may be in the rose and in the stone, for I have myself engendered the thought and am present in it, and so I know what is in it.”

In truth, thought is most completely our possession. If we can find the relation of thought to the Cosmos, to the Universe, we shall find the relation to the Cosmos of what is most completely ours. This can assure us that we have here a fruitful standpoint from which to observe the relation of man to the universe. We will therefore embark on this course; it will lead us to significant heights of anthroposophical observation.

In the present lecture we shall have to prepare a groundwork which may perhaps appear to many of you as somewhat abstract. But later on we shall see that we need this groundwork and that without it we could approach only with a certain superficiality the high goals we shall be striving to attain.

We can thus start from the conviction that when man holds to that which he possesses in his thought, he can find an intimate relation of his being to the Cosmos. But in starting from this point of view we do encounter a difficulty, a great difficulty—not for our understanding but in practice. For it is indeed true that a man lives within every fibre of his thought, and therefore must be able to know his thought more intimately than he can know any perceptual image, but—yes—most people have no thoughts! And as a rule this is not thoroughly realized, for the simple reason that one must have thoughts in order to realize it. What hinders people in the widest circles from having thoughts is that for the ordinary requirements of life they have no need to go as far as thinking; they can get along quite well with words. Most of what we call “thinking” in ordinary life is merely a flow of words: people think in words, and much more often than is generally supposed. Many people, when they ask for an explanation of something, are satisfied if the reply includes some word with a familiar ring, reminding them of this or that. They take the feeling of familiarity for an explanation and then fancy they have grasped the thought

Indeed, this very tendency led at a certain time in the evolution of intellectual life to an outlook which is still shared by many persons who call themselves “thinkers”. For the new edition of my Welt- und Lebensanschauungen im neunzehnten Jahrhundert (Views of the World and of Life in the Nineteenth Century).1First published (two volumes) in Berlin, 1900–1. In 1914 the contents were recast and published in a different form as Die Rätsel der Philosophie (Riddles of Philosophy). See Riddles of Philosophy, Anthroposophic Press, New York, 1974. I tried to rearrange the book quite thoroughly, first by prefacing it with an account of the evolution of Western thought from the sixth century B.C. up to the nineteenth century A.D., and then by adding to the original conclusion a description of spiritual life in terms of thinking up to our own day. The content of the book has also been rearranged in many ways, for I have tried to show how thought as we know it really appeared first in a certain specific period. One might say that it first appeared in the sixth or eighth century B.C. Before then the human soul did not at all experience what can be called “thought” in the true sense of the word. What did human souls experience previously? They experienced pictures; all their experience of the external world took the form of pictures. I have often spoken of this from certain points of view. This picture-experience is the last phase of the old clairvoyant experience. After that, for the human soul, the “picture” passes over into “thought”.

My intention in this book was to bring out this finding of Spiritual Science purely by tracing the course of philosophic evolution. Strictly on this basis, it is shown that thought was born in ancient Greece, and that as a human experience it sprang from the old way of perceiving the external world in pictures. I then tried to show how thought evolves further in Socrates, Plato, Aristotle; how it takes certain forms; how it develops further; and then how, in the Middle Ages, it leads to something of which I will now speak.

The development of thought leads to a stage of doubting the existence of what are called “universals”, general concepts, and thus to so-called Nominalism, the view that universals can be no more than “names”, nothing but words. And this view is still widely held today.

In order to make this clear, let us take a general concept that is easily observable—the concept “triangle”. Now anyone still in the grip of Nominalism of the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries will say somewhat as follows: “Draw me a triangle!” Good! I will draw a triangle for him:

“Right!” says he, “that is a quite specific triangle with three acute angles. But I will draw you another.” And he draws a right-angled triangle, and another with an obtuse angle.

Then says the person in question: “Well, now we have an acute-angled triangle, a right-angled triangle and an obtuse-angled triangle. They certainly exist. But they are not the triangle. The collective or general triangle must contain everything that a triangle can contain. But a triangle that is acute-angled cannot be at the same time right-angled and obtuse-angled. Hence there cannot be a collective triangle. ‘Collective’ is an expression that includes the specific triangles, but a general concept of the triangle does not exist. It is a word that embraces the single details.”

Naturally, this goes further. Let us suppose that someone says the word “lion”. Anyone who takes his stand on the basis of Nominalism may say: “In the Berlin Zoo there is a lion; in the Hanover Zoo there is also a lion; in the Munich Zoo there is still another. There are these single lions, but there is no general lion connected with the lions in Berlin, Hanover and Munich; that is a mere word which embraces the single lions.” There are only separate things; and beyond the separate things—so says the Nominalist—we have nothing but words that comprise the separate things.

As I have said, this view is still held today by many clear-thinking logicians. And anyone who tries to explain all this will really have to admit: “There is something strange about it; without going further in some way I can't make out whether there really is or is not this ‘lion-in-general’ and the ‘triangle-in-general’. I find it far from clear.” And now suppose someone came along and said: “Look here, my dear chap, I can't let you off with just showing me the Berlin or Hanover or Munich lion. If you declare that there is a lion-in-general, then you must take me somewhere where it exists. If you show me only the Berlin, Hanover, or Munich lion, you have not proved to me that a ‘lion-in-general’ exists.” ... If someone were to come along who held this view, and if you had to show him the “lion-in-general”, you would be in a difficulty. It is not so easy to say where you would have to take him.

We will not go on just yet to what we can learn from Spiritual Science; that will come in time. For the moment we will remain at the point which can be reached by thinking only, and we shall have to say to ourselves: “On this ground, we cannot manage to lead any doubter to the ‘lion-in-general.’ It really can't be done.” Here we meet with one of the difficulties which we simply have to admit. For if we refuse to recognize this difficulty in the domain of ordinary thought, we shall not admit the difficulty of human cognition in general.

Let us keep to the triangle, for it makes no difference to the thing-in-general whether we clarify the question by means of the triangle, the lion, or something else. At first it seems hopeless to think of drawing a triangle that would contain all characteristics, all triangles. And because it not only seems hopeless, but is hopeless for ordinary human thinking, therefore all conventional philosophy stands here at a boundary-line, and its task should be to make a proper acknowledgment that, as conventional philosophy, it does stand at a boundary-line. But this applies only to conventional philosophy. There is a possibility of passing beyond the boundary, and with this possibility we will now make ourselves acquainted.

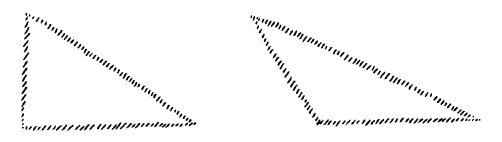

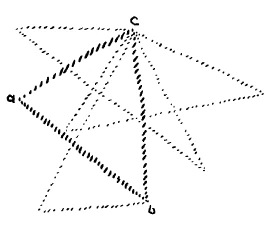

Let us suppose that we do not draw the triangle so that we simply say: Now I have drawn you a triangle, and here it is: In that case the objection could always be raised that it is an acute-angled triangle; it is not a general triangle. The triangle can be drawn differently. Properly speaking it cannot, but we shall soon see how this “can” and “cannot” are related to one another. Let us take this triangle that we have here, and let us allow each side to move as it will in any direction, and moreover we allow it to move with varying speeds, so that next moment the sides take, e.g., these positions:

In short, we arrive at the uncomfortable notion of saying: I will not only draw a triangle and let it stay as it is, but I will make certain demands on your imagination. You must think to yourself that the sides of the triangle are in continual motion. When they are in motion, then out of the form of the movements there can arise simultaneously a right-angled, or an obtuse-angled triangle, or any other.

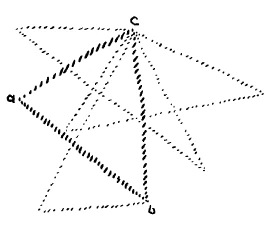

In this field we can do and also require two different things. We can first make it all quite easy; we draw a triangle and have done with it. We know how it looks and we can rest comfortably in our thoughts, for we have got what we want. But we can also take the triangle as a starting-point, and allow each side to move in various directions and at different speeds. In this case it is not quite so easy; we have to carry out movements in our thought. But in this way we really do lay hold of the triangle in its general form; we fail to get there only if we are content with one triangle. The general thought, “triangle”, is there if we keep the thought in continual movement, if we make it versatile.

This is just what the philosophers have never done; they have not set their thoughts into movement. Hence they are brought to a halt at a boundary-line, and they take refuge in Nominalism.

We will now translate what I have just been saying into a language that we know, that we have long known. If we are to rise from the specific thought to the general thought, we have to bring the specific thought into motion; thus thought in movement becomes the “general thought” by passing constantly from one form into another. “Form”, I say; rightly understood, this means that the whole is in movement, and each entity brought forth by the movement is a self-contained form. Previously I drew only single forms: an acute-angled, a right-angled, and an obtuse-angled triangle. Now I am drawing something—as I said, I do not really draw it—but you can picture to yourselves what the idea is meant to evoke—the general thought is in motion, and brings forth the single forms as its stationary states.

“Forms”, I said—hence we see that the philosophers of Nominalism, who stand before a boundary-line, go about their work in a certain realm, the realm of the Spirits of Form. Within this realm, which is all around us, forms dominate; and therefore in this realm we find separate, strictly self-contained forms. The philosophers I mean have never made up their minds to go outside this realm of forms, and so, in the realm of universals, they can recognize nothing but words, veritably mere words. If they were to go beyond the realm of specific entities—i.e. of forms—they would find their way to mental pictures which are in continual motion; that is, in their thinking they would come to a realization of the realm of the Spirits of Movement—the next higher Hierarchy. But these philosophers will not condescend to that. And when in recent times a Western thinker did consent to think correctly in this way, he was little understood, although much was said and much nonsense talked about him. Turn to what Goethe wrote in his “Metamorphosis of Plants” and see what he called the “primal plant” (Urpflanze), and then turn to what he called the “primal animal” (Urtier) and you will find that you can understand these concepts “primal plant” and “primal animal” only if your thoughts are mobile—when you think in mobile terms. If you accept this mobility, of which Goethe himself speaks, you are not stuck with an isolated concept bounded by fixed forms. You have the living element which ramifies through the whole evolution of the animal kingdom, or the plant-kingdom, and creates the forms. During this process it changes—as the triangle changes into an acute-angled or an obtuse-angled one—becoming now “wolf”, now “lion”, now “beetle”, in accordance with the metamorphoses of its mobility during its passage through the particular entities. Goethe brought the petrified formal concepts into movement. That was his great central act; his most significant contribution to the nature-study of his time.

You see here an example of how Spiritual Science is in fact adapted to leading men out of the fixed assumptions to which they cannot help clinging today, even if they are philosophers. For without concepts gained through Spiritual Science it is not possible, if one is sincere, to concede that general categories can be anything more than “mere words”. That is why I said that most people have no real thoughts, but merely a flow of words, and if one speaks to them of thoughts, they reject it.

When does one speak to people of “thoughts”? When, for example, one says that animals have Group-souls. For it amounts to the same whether one says “collective thoughts” or “group-souls” (we shall see in the course of these lectures what the connection is between the two). But the Group-soul cannot be understood except by thinking of it as being in motion, in continual external and internal motion; otherwise one does not come to the Group-soul. But people reject that. Hence they reject the Group-soul, and equally the collective thought.

For getting to know the outside world you need no thoughts; you need only a remembrance of what you have seen in the kingdom of form. That is all most people know, and for them, accordingly, general thoughts remain mere words. And if among the many different Spirits of the higher Hierarchies there were not the Genius of Speech—who forms general words for general concepts—men themselves would not come to it. Thus their first ideas of things-in-themselves come to men straight out of language itself, and they know very little about such ideas except in so far as language preserves them.

We can see from this that there must be something peculiar about the thinking of real thoughts. And this will not surprise us if we realize how difficult it really is for men to attain to clarity in the realm of thought. In ordinary, external life, when a person wants to brag a little, he will often say that “thinking is easy”. But it is not easy, for real thinking always demands a quite intimate, though in a certain sense unconscious, impulse from the realm of the Spirits of Movement. If thinking were so very easy, then such colossal blunders would not be made in the region of thought. Thus, for more than a century now, people have worried themselves over a thought I have often mentioned—a thought formulated by Kant.

Kant wanted to drive out of the field the so-called “ontological proof of God”. This ontological proof of God dates from the time of Nominalism, when it was said that nothing general existed which corresponded to general or collective thoughts, as single, specific objects correspond to specific thoughts. The argument says, roughly: If we presuppose God, then He must be an absolutely perfect Being. If He is an absolutely perfect Being, then He must not lack “being”, i.e. existence, for otherwise there would be a still more perfect Being who would possess those attributes one has in mind, and would also exist. Thus one must think that the most perfect Being actually exists. One cannot conceive of God as otherwise than existing, if one thinks of Him as the most perfect Being. That is: out of the concept itself one can deduce that, according to the ontological proof, there must be God.

Kant tried to refute this proof by showing that out of a “concept” one could not derive the existence of a thing, and for this he coined the famous saying I have often mentioned: A hundred actual thalers are not less and not more than a hundred possible thalers. That is, if a thaler has three hundred pfennigs, then for each one of a hundred possible thalers one must reckon three hundred pfennigs: and in like manner three hundred pfennigs for each of a hundred actual thalers. Thus a hundred possible thalers contain just as much as a hundred actual thalers, i.e. it makes no difference whether I think of a hundred actual or a hundred possible thalers. Hence one may not derive existence from the mere thought of an absolutely perfect Being, because the mere thought of a possible God would have the same attributes as the thought of an actual God.

That appears very reasonable. And yet for a century people have been worrying themselves as to how it is with the hundred possible and the hundred actual thalers. But let us take a very obvious point of view, that of practical life; can one say from this point of view that a hundred actual thalers do not contain more than a hundred possible ones? One can say that a hundred actual thalers contain exactly a hundred thalers more than do a hundred possible ones! And it is quite clear: if you think of a hundred possible thalers on one side and of a hundred actual thalers on the other, there is a difference. On this other side there are exactly a hundred thalers more. And in most real cases it is just on the hundred actual thalers that the question turns.

But the matter has a deeper aspect. One can ask the question: What is the point in the difference between a hundred possible and a hundred actual thalers? I think it would be generally conceded that for anyone who can acquire the hundred thalers, there is beyond doubt a decided difference between a hundred possible thalers and a hundred actual ones. For imagine that you are in need of a hundred thalers, and somebody lets you choose whether he is to give you the hundred possible or the hundred actual thalers. If you can get the thalers, the whole point is the difference between the two kinds. But suppose you were so placed that you cannot in any way acquire the hundred thalers, then you might feel absolutely indifferent as to whether someone did not give you a hundred possible or a hundred actual thalers. When a person cannot have them, then a hundred actual and a hundred possible thalers are in fact of exactly the same value.

This is a significant point. And the significance is this—that the way in which Kant spoke about God could occur only at a time when men could no longer “have God” through human soul-experience. As He could not be reached as an actuality, then the concept of the possible God or of the actual God was immaterial, just as it is immaterial whether one is not to have a hundred actual or a hundred possible thalers. If there is no path for the soul to the true God, then certainly no development of thought in the style of Kant can lead to Him.

Hence we see that the matter has this deeper side also. But I have introduced it only because I wanted to make it clear that when the question becomes one of “thinking”, then one must go somewhat more deeply. Errors of thought slip out even among the most brilliant thinkers, and for a long time one does not see where the weak spot of the argument lies—as, for example, in the Kantian thought about the hundred possible and the hundred actual thalers. In thinking, one must always take account of the situation in which the thought has to be grasped.

By discussing first the nature of general concepts, and then the existence of such errors in thinking as this Kantian one, I have tried to show you that one cannot properly reflect on ways of thinking without going deeply into actualities. I will now approach the matter from yet another side, a third side.

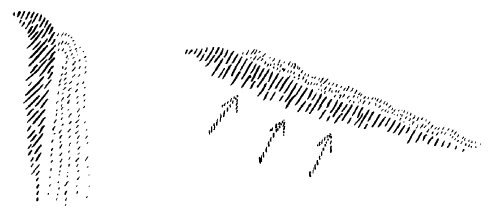

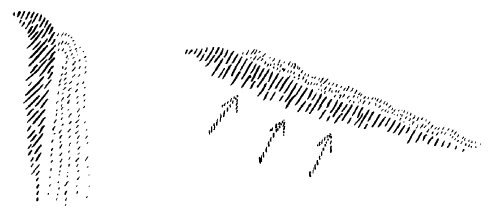

Let us suppose that we have here a mountain or hill, and beside it, a steep slope. On the slope there is a spring and the flow from it leaps sheer down, a real waterfall. Higher up on the same slope is another spring; the water from it would like to leap down in the same way, but it does not. It cannot behave as a waterfall, but runs down nicely as a stream or beck. Is the water itself endowed with different forces in these two cases? Quite clearly not. For the second stream would behave just as the first stream does if it were not obstructed by the shape of the mountain. If the obstructive force of the mountain were not present, the second stream would go leaping down. Thus we have to reckon with two forces: the obstructive force of the mountain and the earth's gravitational pull, which turns the first stream into a waterfall. The gravitational force acts also on the second stream—one can see how it brings the stream flowing down. But a skeptic could say that in the case of the second stream this is not at all obvious, whereas in the first stream every particle of water goes hurtling down. In the case of the second stream we must reckon in at every point the obstructing force of the mountain, which acts in opposition to the earth's gravitational pull.

Now suppose someone came along and said: “I don't altogether believe what you tell me about the force of gravity, nor do I believe in the obstructing force. Is the mountain the cause of the stream taking a particular path? I don't believe it.” “Well, what do you believe?” one might ask. He replies: “I believe that part of the water is down there, above it is more water, above that more water again, and so on. I believe the lower water is pushed down by the water above it, and this water by the water above it. Each part of the water drives down the water below it.” Here is a noteworthy distinction. The first man declares: “Gravity pulls the water down.” The second man says: “Masses of water are perpetually pushing down the water below them: that is how the water comes down from above.”

Obviously anyone who spoke of a “pushing down” of this kind would be very silly. But suppose it is a question not of a beck or stream but of the history of mankind, and suppose someone like the person I have just described were to say: “The only thing I believe of what you tell me is this: we are now living in the twentieth century, and during it certain events have taken place. They were brought about by similar ones during the last third of the nineteenth century; these again were caused by events in the second third of the nineteenth century, and these again by those in the first third.” That is what is called “pragmatic history”, in which one always speaks of “causes and effects”, so that subsequent events are always explained by means of preceding ones. Just as someone might deny the force of gravity and say that the masses of water are continually pushing one another forward, so it is when someone is pursuing pragmatic history and explains the condition of the nineteenth century as a result of the French Revolution.

In reply to a pragmatic historian we would of course say: “No, other forces are active besides those that push from behind—which in fact are not there at all in the true sense. For just as little as there are forces pushing the stream from behind, just as little do preceding events push from behind in the history of humanity. Fresh influences are always coming out of the spiritual world—just as in the stream the force of gravity is always at work—and these influences cross with other forces, just as the force of gravity crosses with the obstructive force of the mountain. If only one force were present, you would see the course of history running quite differently. But you do not see the individual forces at work in history. You see only the physical ordering of the world: what we would call the results of the Saturn, Moon and Sun stages in the evolution of the Earth. You do not see all that goes on continually in human souls, as they live through the spiritual world and then come down again to Earth. All this you simply deny.”

But there is today a conception of history which is just what we would expect from somebody who came along with ideas such as those I have described, and it is by no means rare. Indeed in the nineteenth century it was looked upon as immensely clever. But what should we be able to say about it from the standpoint we have gained? If anyone were to explain the mountain stream in this “pragmatic” way, he would be talking utter nonsense. How is it then that he upholds the same nonsense with regard to history? The reason is simply that he does not notice it! And history is so complicated that it is almost everywhere expounded as “pragmatic history”, and nobody notices it.

We can certainly see from this that Spiritual Science, which has to develop sound principles for the understanding of life, has work to do in the most varied domains of life; and that it is first of all necessary to learn how to think, and to get to know the inner laws and impulses of thought. Otherwise all sorts of grotesque things can befall one. Thus for example a certain man to-day is stumbling and bumbling over the problem of “thought and language”. He is the celebrated language-critic Fritz Mauthner, who has also written lately a large philosophical dictionary. His bulky Critique of Language is already in its third edition, so for our contemporaries it is a celebrated work. There are plenty of ingenious things in this book, and plenty of dreadful ones. Thus one can find here a curious example of faulty thinking—and one runs up against such blunders in almost every five lines—which leads the worthy Mauthner to throw doubt on the need for logic. “Thinking”, for him, is merely speaking; hence there is no sense in studying logic; grammar is all one needs. He says also that since there is, rightly speaking, no logic, logicians are fools. And then he says: In ordinary life, opinions are the result of inferences, and ideas come from opinions. That is how people go on! Why should there be any need for logic when we are told that opinions arise from inferences, and ideas from opinions? It is just as clever as if someone were to say: “Why do you need botany? Last year and two years ago the plants were growing.” But such is the logic one finds in a man who prohibits logic. One can quite understand that he does prohibit it. There are many more remarkable things in this strange book—a book that, in regard to the relation between thought and language, leads not to lucidity but to confusion.

I said that we need a substructure for the things that are to lead us to the heights of spiritual contemplation. Such a substructure as has been put forward here may appear to many as somewhat abstract; still, we shall need it. And I think I have tried to make it so easy that what I have said is clear enough. I should like particularly to emphasise that through such simple considerations as these one can get an idea of where the boundary lies between the realm of the Spirits of Form and the realm of the Spirits of Movement. But whether one comes to such an idea is intimately connected with whether one is prepared to admit thoughts of things-in-general, or whether one is prepared to admit only ideas or concepts of individual things—I say expressly “is prepared to admit”.

On these expositions—to which, as they are somewhat abstract, I will add nothing further—we will build further in the next lecture.

Erster Vortrag

In diesen vier Vorträgen, die ich im Verlaufe unserer Generalversammlung vor Ihnen werde zu halten haben, möchte ich sprechen über den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Weltall von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus. Und diesen Gesichtspunkt möchte ich mit folgenden Worten andeuten.

Der Mensch erlebt in sich das, was wit den Gedanken nennen können, und in dem Gedanken kann sich der Mensch als etwas unmittelbar Tätiges, als etwas, was seine Tätigkeit überschauen kann, erfühlen. Wenn wir irgendein äußeres Ding betrachten, zum Beispiel eine Rose oder einen Stein, und wir stellen dieses äußere Ding vor, so kann jemand mit Recht sagen: Du kannst niemals eigentlich wissen, wieviel du in dem Steine oder in der Rose, indem du sie vorstellst, von dem Ding, von der Pflanze, eigentlich hast. Du siehst die Rose, ihre äußere Röte, ihre Form, wie sie in einzelne Blumenblätter abgeteilt ist, du siehst den Stein mit seiner Farbe, mit seinen verschiedenen Ecken, aber du mußt dir immer sagen: Da kann noch etwas drinnenstecken, was dir nicht nach außen hin erscheint. Du weißt nicht, wieviel du in deiner Vorstellung von dem Steine, von der Rose eigentlich hast.

Wenn aber jemand einen Gedanken hat, dann ist er es selber, der diesen Gedanken macht. Man möchte sagen, in jeder Faser dieses seines Gedankens ist er drinnen. Daher ist er für den ganzen Gedanken ein Teilnehmer seiner Tätigkeit. Er weiß: Was in dem Gedanken ist, das habe ich so in den Gedanken hineingedacht, und was ich nicht in den Gedanken hineingedacht habe, das kann auch nicht in ihm drinnen sein. Ich überschaue den Gedanken. Keiner kann behaupten, wenn ich einen Gedanken vorstelle, da könnte in dem Gedanken noch soundso viel anderes drinnen sein wie in der Rose und in dem Stein; denn ich habe ja selber den Gedanken erzeugt, bin in ihm gegenwärtig, weiß also, was drinnen ist.

Wirklich, der Gedanke ist unser Ureigenstes. Finden wir die Beziehung des Gedankens zum Kosmos, zum Weltall, dann finden wir die Beziehung unseres Ureigensten zum Kosmos, zum Weltall. Das kann uns versprechen, daß es wirklich ein fruchtbarer Gesichtspunkt ist, einmal die Beziehung des Menschen zum Weltall vom Gedanken aus zu betrachten. Wir werden also diese Betrachtung anstellen, und sie wird uns in bedeutsame Höhen anthroposophischer Betrachtung führen. Aber wir werden heute einen Unterbau aufzurichten haben, der vielleicht manchem von Ihnen etwas abstrakt vorkommen mag. Aber in den nächsten Tagen werden wir sehen, daß wir diesen Unterbau brauchen und daß wir ohne ihn uns nur mit einer gewissen Oberflächlichkeit den hohen Zielen nähern können, die wir in diesen vier Vorträgen anstreben. Das also, was eben gesagt worden ist, verspricht uns, daß der Mensch, wenn et sich an das hält, was er im Gedanken hat, eine intime Beziehung seines Wesens zum Weltall, zum Kosmos, finden kann.

Nur hat die Sache eine Schwierigkeit, wenn wir uns auf diesen Gesichtspunkt begeben wollen, eine große Schwierigkeit. Ich meine nicht für unsere Betrachtung, aber für den objektiven Tatbestand hat es eine große Schwierigkeit. Und diese Schwierigkeit besteht darin, daß es zwar wahr ist, daß man in jeder Faser des Gedankens drinnen lebt und daher den Gedanken, wenn man ihn hat, von allen Vorstellungen am intimsten kennen muß; aber, ja aber — die meisten Menschen haben keine Gedanken! Und dies wird gewöhnlich nicht mit aller Gründlichkeit durchdacht, daß die meisten Menschen keine Gedanken haben. Aus dem Grunde wird es nicht mit aller Gründlichkeit durchdacht, weil man dazu - eben Gedanken brauchte! Auf eines muß zunächst aufmerksam gemacht werden. Was im weitesten Umkreise unseres Lebens die Menschen verhindert, Gedanken zu haben, das ist, daß die Menschen für den gewöhnlichen Gebrauch des Lebens gar nicht immer das Bedürfnis haben, wirklich bis zum Gedanken vorzudringen, sondern daß sie statt des Gedankens sich mit dem Worte begnügen. Das meiste von dem, was man im gewöhnlichen Leben Denken nennt, verläuft nämlich in Worten. Man denkt in Worten. Viel mehr, als man glaubt, denkt man in Worten. Und viele Menschen sind, wenn sie nach einer Erklärung von dem oder jenem verlangen, damit zufrieden, daß man ihnen irgendein Wort sagt, das einen für sie bekannten Klang hat, das sie an dieses oder jenes erinnert; und dann halten sie das, was sie bei einem solchen Wort empfinden, für eine Erklärung und glauben, sie hätten dann den Gedanken.

Ja, das, was ich eben gesagt habe, das hat in der Entwickelung des menschlichen Geisteslebens zu einer bestimmten Zeit dazu geführt, eine Ansicht heraufzubringen, welche heute noch viele Menschen, die sich Denker nennen, teilen. In der Neuauflage meiner «Welt- und Lebensanschauungen im neunzehnten Jahrhundert» habe ich versucht, dieses Buch ganz gründlich umzugestalten, indem ich eine Entwickelungsgeschichte des abendländischen Gedankens vorausgeschickt habe, angefangen vom 6. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert bis herauf ins 19. Jahrhundert, und indem ich dann am Schlusse zu dem, was gegeben war, als das Buch zuerst erschien, hinzufügte eine Darstellung des, sagen wir, gedanklichen Geisteslebens bis in unsere Tage herein. Auch der Inhalt, der schon da war, ist vielfach umgestaltet worden. Da habe ich denn zu zeigen gehabt, wie der Gedanke in einem bestimmten Zeitalter eigentlich erst entsteht. Er entsteht wirklich erst, man könnte sagen, um das 6. oder 8. vorchristliche Jahrhundert. Vorher erlebten die menschlichen Seelen gar nicht das, was man im rechten Sinne des Wortes Gedanken nennen kann. Was erlebten die menschlichen Seelen vorher? Sie erlebten vorher Bilder. Und alles Erleben der Außenwelt geschah in Bildern. Von gewissen Gesichtspunkten aus habe ich das oftmals gesagt. Dieses Bilder-Erleben ist die letzte Phase des alten hellseherischen Erlebens. Dann geht für die menschliche Seele das Bild in den Gedanken über.

Was ich in diesem Buche beabsichtigte, ist, dieses Ergebnis der Geisteswissenschaft einmal rein durch Verfolgung der philosophischen Entwickelung zu zeigen. Ganz nur auf dem Boden der philosophischen Wissenschaft bleibend, wird gezeigt, daß der Gedanke einmal im alten Griechenland geboren worden ist, daß er entsteht dadurch, daß er herausspringt für das menschliche Seelenerleben aus dem alten sinnbildlichen Erleben der Außenwelt. Dann versuchte ich zu zeigen, wie dieser Gedanke weitergeht in So£rates, in Plato, Aristoteles, wie er bestimmte Formen annimmt, wie er sich weiter heraufentwickelt und dann im Mittelalter zu dem führt, was ich jetzt erwähnen will.

Zu dem Zweifel führt die Entwickelung des Gedankens, ob es dasjenige überhaupt geben könne in der Welt, was man allgemeine Gedanken, allgemeine Begriffe nennt, zu dem sogenannten Nominalismus, zu der philosophischen Anschauung, daß die allgemeinen Begriffe nur Namen sein können, also überhaupt nur Worte. Es gab also für diesen allgemeinen Gedanken sogar die philosophische Anschauung, und viele haben sie noch heute, daß diese allgemeinen Gedanken überhaupt nur Worte sein können.

Nehmen wir einmal, um uns das zu verdeutlichen, was eben gesagt worden ist, einen leicht überschaubaren und zwar allgemeinen Begriff; nehmen wir den Begriff «Dreieck» als allgemeinen Begriff. Derjenige nun, der da mit seinem Standpunkte des Nominalismus kommt, der nicht hinwegkommen kann von dem, was als Nominalismus sich in dieser Beziehung ausgebildet hat in der Zeit des 11. bis 13. Jahrhunderts, der sagt etwa folgendes: Zeichne mir ein Dreieck hin! — Gut, ich werde ihm ein Dreieck hinzeichnen, zum Beispiel ein solches:

Schön, sagt er, das ist ein besonderes, spezielles Dreieck mit drei spitzen Winkeln, das gibt es. Aber ich werde dir ein anderes hinzeichnen. - Und er zeichnet ein Dreieck hin, das einen rechten Winkel hat, und ein solches, das einen sogenannten stumpfen Winkel hat.

So, jetzt nennen wir das erste ein spitzwinkliges Dreieck, das zweite ein rechtwinkliges und das dritte ein stumpfwinkliges. Da sagt der Betreffende: Das glaube ich dir, es gibt ein spitzwinkliges, ein rechtwinkliges und ein stumpfwinkliges Dreieck. Aber das alles ist ja nicht das Dreieck. Das allgemeine Dreieck muß alles enthalten, was ein Dreieck enthalten kann. Unter den allgemeinen Gedanken des Dreiecks muß das erste, das zweite und das dritte Dreieck fallen. Es kann aber doch nicht ein Dreieck, das spitzwinklig ist, zugleich rechtwinklig und stumpfwinklig sein. Ein Dreieck, das spitzwinklig ist, ist ein spezielles, ist nicht ein allgemeines Dreieck; ebenso ist ein rechtwinkliges und ein stumpfwinkliges Dreieck ein spezielles. Ein allgemeines Dreieck kann es aber nicht geben. Also ist das allgemeine Dreieck ein Wort, das die speziellen Dreiecke zusammenfaßt. Aber den allgemeinen Begriff des Dreiecks gibt es nicht. Das ist ein Wort, das die Einzelheiten zusammenfaßt.

Das geht natürlich weiter. Nehmen wir an, es spricht jemand das Wort Löwe aus. Nun sagt der, welcher auf dem Standpunkt des Nominalismus steht: Im Berliner Tiergarten ist ein Löwe, im Hannoverschen Tiergarten ist auch ein Löwe, im Münchner Tiergarten ist auch einer. Die einzelnen Löwen gibt es; aber einen allgemeinen Löwen, der etwas zu tun haben sollte mit dem Berliner, Hannoverschen und Münchner Löwen, den gibt es nicht. Das ist ein bloßes Wort, das die einzelnen Löwen zusammenfaßt. Es gibt nur einzelne Dinge, und es gibt außer den einzelnen Dingen, so sagt der Nominalist, nichts als Worte, welche die einzelnen Dinge zusammenfassen.

Diese Anschauung, wie gesagt, ist heraufgekommen; sie vertreten heute noch scharfsinnige Logiker. Und wer sich die Sache, die jetzt eben auseinandergesetzt worden ist, ein wenig überlegt, wird sich auch im Grunde genommen gestehen müssen: Es liegt da doch etwas Besonderes vor; ich kann nicht so ohne weiteres darauf kommen, ob es nun wirklich diesen «Löwen im allgemeinen» und das «Dreieck im allgemeinen» gibt, denn ich sehe es ja nicht recht. Wenn nun wirklich jemand käme, der sagen würde: Sieh einmal, lieber Freund, ich kann dir nicht zubilligen, daß du mir den Münchner, den Hannoverschen oder den Berliner Löwen zeigst. Wenn du behauptest, es gäbe den Löwen «im allgemeinen», so mußt du mich irgendwo hinführen, wo es den «Löwen im allgemeinen» gibt. Wenn du mir aber den Münchner, den Hannoverschen und den Berliner Löwen zeigst, so hast du mir nicht bewiesen, daß es den «Löwen im allgemeinen» gibt. - Wenn jemand käme, der diese Anschauung hat, und man sollte ihm den «Löwen im allgemeinen» zeigen, so würde man zunächst etwas in Verlegenheit geraten. Es ist nicht so leicht, die Frage zu beantworten, wo man den Betreffenden hinführen soll, dem man den «Löwen im allgemeinen» zeigen soll.

Nun, wir wollen jetzt nicht zu dem gehen, was uns die Geisteswissenschaft gibt; das wird schon noch kommen. Wir wollen einmal beim Denken bleiben, wollen bei dem bleiben, was dutch das Denken erreicht werden kann, und wir werden uns sagen müssen: Wenn wir auf diesem Boden bleiben wollen, so geht es eben nicht recht, daß wir irgendeinen Zweifler zum «Löwen im allgemeinen» hinführen. Das geht wirklich nicht. Hier liegt eine der Schwierigkeiten vor, die man einfach zugeben muß. Denn will man auf dem Gebiete des gewöhnlichen Denkens diese Schwierigkeit nicht zugeben, dann läßt man sich eben nicht auf die Schwierigkeit des menschlichen Denkens überhaupt ein.

Bleiben wir beim Dreieck; denn schließlich ist es für die allgemeine Sache gleichgültig, ob wir uns die Sache am Dreieck, am Löwen oder an etwas anderem klarmachen. Zunächst erscheint es aussichtslos, daß wir ein allgemeines Dreieck hinzeichnen, das alle Eigenschaften, alle Dreiecke enthält. Und weil es aussichtslos nicht nur erscheint, sondern für das gewöhnliche menschliche Denken auch ist, deshalb steht hier alle äußere Philosophie an einer Grenzscheide, und ihre Aufgabe wäre es, sich einmal wirklich zu gestehen, daß sie als äußere Philosophie an einer Grenzscheide steht. Aber diese Grenzscheide ist eben nur diejenige der äußeren Philosophie. Über diese Grenzscheide gibt es doch eine Möglichkeit, hinüberzukommen, und mit dieser Möglichkeit wollen wir uns jetzt einmal bekanntmachen.

Denken wir uns, wir zeichnen das Dreieck nicht einfach so hin, daß wir sagen: Jetzt habe ich dir ein Dreieck hingezeichnet, und da ist es. - Da wird immer der Einwand gemacht werden können: Das ist eben ein spitzwinkliges Dreieck, das ist kein allgemeines Dreieck. Man kann das Dreieck nämlich auch anders hinzeichnen. Eigentlich kann man es nicht; aber wir werden gleich sehen, wie sich dieses Können und Nichtkönnen zueinander verhalten. Nehmen wir an, dieses Dreieck, das wir hier haben, zeichnen wir so hin und erlauben jeder einzelnen Seite, daß sie sich nach jeder Richtung, wie sie will, bewegt. Und zwar erlauben wir ihr, daß sie sich mit verschiedenen Schnelligkeiten bewege (an der Tafel zeichnend gesprochen):

Diese Seite bewegt sich so, daß sie im nächsten Augenblick diese Lage einnimmt, diese so, daß sie im nächsten Augenblick diese Lage einnimmt. Diese bewegt sich viel langsamer, diese bewegt sich schneller und so weiter. Jetzt kehrt sich die Richtung um

Kurz, wir begeben uns in die unbequeme Vorstellung hinein, daß wir sagen: Ich will nicht nur ein Dreieck hinzeichnen und es so dann stehen lassen, sondern ich stelle an dein Vorstellen gewisse Anforderungen. Du mußt dir denken, daß die Seiten des Dreiecks fortwährend in Bewegung sind. Wenn sie in Bewegung sind, dann kann ein rechtwinkliges oder ein stumpfwinkliges Dreieck oder jedes andere gleichzeitig aus der Form der Bewegungen hervorgehen.

Zweierlei kann man machen und auch verlangen auf diesem Gebiete. Das erste, was man verlangen kann, ist, daß man es hübsch bequem hat. Wenn jemand einem ein Dreieck aufzeichnet, dann ist es fertig, und man weiß, wie es aussieht; jetzt kann man hübsch ruhen in seinen Gedanken, denn man hat, was man will. Man kann aber auch das andere machen: das Dreieck gleichsam als einen Ausgangspunkt betrachten und jeder Seite erlauben, daß sie sich mit verschiedenen Geschwindigkeiten und nach verschiedenen Richtungen dreht. In diesem Falle hat man es aber nicht so bequem, sondern man muß in seinen Gedanken Bewegungen ausführen. Aber dafür hat man auch wirklich den allgemeinen Gedanken Dreieck darinnen; et ist ja nur nicht zu erreichen, wenn man bei einem Dreieck abschließen will. Der allgemeine Gedanke Dreieck ist da, wenn man den Gedanken in fortwährender Bewegung hat, wenn er versatil ist.

Weil die Philosophen das, was ich eben jetzt ausgesprochen habe, den Gedanken in Bewegung zu bringen, nicht gemacht haben, deshalb stehen sie notwendigerweise an einer Grenzscheide und begründen den Nominalismus. Jetzt wollen wir uns das, was ich eben jetzt ausgesprochen habe, in eine uns bekannte Sprache übersetzen, in eine uns längst bekannte Sprache.

Gefordert wird von uns, wenn wir von dem speziellen Gedanken zu dem allgemeinen Gedanken aufsteigen sollen, daß wir den speziellen Gedanken in Bewegung bringen, so daß der bewegte Gedanke der allgemeine Gedanke ist, der von einer Form in die andere hineinschlüpft. Form sage ich; richtig gedacht ist: Das ganze bewegt sich, und jedes einzelne, was da herauskommt durch die Bewegung, ist eine in sich abgeschlossene Form. Früher habe ich nur Einzelformen hingezeichnet, ein spitzwinkliges, ein rechtwinkliges und ein stumpfwinkliges Dreieck. Jetzt zeichne ich etwas auf - ich zeichne es eigentlich nicht auf, das sagte ich schon, aber vorstellen kann man sich das -, was die Vorstellung hervorrufen soll, daß der allgemeine Gedanke in Bewegung ist und die einzelne Form durch sein Stillestehen erzeugt - «die Form erzeugt, sage ich.

Da sehen wir, die Philosophen des Nominalismus, die notwendig an einer Grenzscheide stehen, bewegen sich in einem gewissen Reiche, in dem Reiche der Geister der Form. Innerhalb des Reiches der Geister der Form, das um uns herum ist, herrschen die Formen; und weil die Formen herrschen, sind in diesem Reiche einzelne, streng in sich abgeschlossene Einzeldinge. Daraus ersehen Sie, daß die Philosophen, die ich meine, niemals den Entschluß gefaßt haben, aus dem Reiche der Formen herauszugehen, und daher in den allgemeinen Gedanken nichts anderes haben können als Worte, richtig bloße Worte. Würden sie herausgehen aus dem Reiche der speziellen Dinge, das heißt der Formen, so würden sie in ein Vorstellen hineinkommen, das in fortwährender Bewegung ist, das heißt, sie würden in ihrem Denken eine Vergegenwärtigung des Reiches der Geister der Bewegung haben, der nächsthöheren Hierarchie. Dazu lassen sich aber die meisten Philosophen nicht herbei. Und als sich einmal einer in der letzten Zeit des abendländischen Denkens herbeigelassen hat, so recht in diesem Sinne zu denken, da wurde er wenig verstanden, obwohl viel von ihm gesprochen und gefaselt wird. Man schlage auf, was Goethe in seiner «Metamorphose der Pflanzen» geschrieben hat, was er die «Urpflanze» nannte; man schlage dann das auf, was er das «Urtier» nannte, und man wird finden, daß man mit diesen Begriffen «Urpflanze», «Urtier» nur zurechtkommt, wenn man sie beweglich denkt. Wenn man diese Beweglichkeit aufnimmt, von der Goethe selber spricht, dann hat man nicht einen abgeschlossenen, in seinen Formen begrenzten Begriff, sondern man hat das, was in seinen Formen lebt, was durchkriecht in der ganzen Entwickelung des Tierreiches oder des Pflanzenteiches, was sich in diesem Durchkriechen ebenso verändert, wie das Dreieck sich in ein spitzwinkliges oder ein stumpfwinkliges verändert, und was bald «Wolf» und «Löwe», bald «Käfer» sein kann, je nachdem die Beweglichkeit so eingerichtet ist, daß die Eigenschaften sich abändern in dem Durchgehen durch die Einzelheiten. Goethe brachte die starren Begriffe der Formen in Bewegung. Das war seine große, zentrale Tat. Das war das Bedeutsame, was er in die Naturbetrachtung seiner Zeit eingeführt hat.

Sie sehen hier an einem Beispiele, wie das, was wir Geisteswissenschaft nennen, tatsächlich dazu geeignet ist, die Menschen aus dem herauszuführen, woran sie notwendig heute haften müssen, selbst wenn sie Philosophen sind. Denn ohne Begriffe, die durch die Geisteswissenschaft gewonnen werden, ist es gar nicht möglich, wenn man ehrlich ist, etwas anderes zuzugeben, als daß die allgemeinen Gedanken bloße Worte seien. Das ist der Grund, warum ich sagte: Die meisten Menschen haben nur keine Gedanken. Und wenn man ihnen von Gedanken spricht, so lehnen sie das ab.

Wann spricht man zu den Menschen von Gedanken? Wenn man zum Beispiel sagt, die Tiere und Pflanzen hätten Gruppenseelen. Ob man sagt allgemeine Gedanken oder Gruppenseelen — wir werden im Laufe der Vorträge sehen, was für eine Beziehung zwischen den beiden ist -, das kommt für das Denken auf dasselbe heraus. Aber die Gruppenseele ist auch nicht anders zu begreifen als dadurch, daß man sie in Bewegung denkt, in fortwährender äußerlicher und innerlicher Bewegung; sonst kommt man nicht zur Gruppenseele. Aber das lehnen die Menschen ab. Daher lehnen sie auch die Gruppenseele ab, lehnen also den allgemeinen Gedanken ab.

Zum Kennenlernen der offenbaren Welt braucht man aber keine Gedanken; da braucht man nur die Erinnerung an das, was man gesehen hat im Reiche der Form. Und das ist das, was die meisten Menschen überhaupt nur wissen: was sie gesehen haben im Reiche der Form. Da bleiben dann die allgemeinen Gedanken bloße Worte. Daher konnte ich sagen: Die meisten Menschen haben keine Gedanken. Denn die allgemeinen Gedanken bleiben für die meisten Menschen nur Worte. Und wenn es unter den mancherlei Geistern der höheren Hierarchien nicht auch den Genius der Sprache geben würde, der die allgemeinen Worte für die allgemeinen Begriffe bildet, die Menschen selber würden das nicht tun. Also richtig aus der Sprache heraus bekommen die Menschen zunächst ihre allgemeinen Gedanken, und sie haben auch nicht viel anderes als die in der Sprache aufbewahrten allgemeinen Gedanken.

Daraus ersehen wir aber, daß es doch etwas Eigenes sein muß mit dem Denken von wirklichen Gedanken. Daß es etwas ganz Eigentümliches damit sein muß, das können wir uns daraus verständlich machen, daß wir sehen, wie schwer es eigentlich den Menschen wird, auf dem Felde des Gedankens zur Klarheit zu kommen. So im äußeren trivialen Leben wird man vielleicht oftmals behaupten, wenn man ein bißchen renommieren will, das Denken sei leicht. Aber es ist nicht leicht. Denn es erfordert das wirkliche Denken immer ein ganz enges, in gewisser Beziehung unbewußtes Berührtsein von einem Hauch aus dem Reiche der Geister der Bewegung. Würde das Denken so ganz leicht sein, so würden nicht so kolossale Schnitzer auf dem Gebiete des Denkens gemacht werden, und man plagte sich nicht so lange mit allerlei Problemen und Irrtümern herum. So plagt man sich jetzt seit mehr als einem Jahrhundert mit einem Gedanken, den ich schon öfter angeführt habe und den Kart ausgesprochen hat.

Kant wollte den sogenannten ontologischen Gottesbeweis aus der Welt schaffen. Dieser ontologische Gottesbeweis stammt auch aus der Zeit des Nominalismus, wo man sagte, daß es für die allgemeinen Begriffe nur Worte gäbe und daß nicht etwas Allgemeines existiere, das den einzelnen Gedanken entsprechen würde wie die einzelnen Gedanken den Vorstellungen. Diesen ontologischen Gottesbeweis will ich als ein Beispiel anführen, wie gedacht wird.

Er sagt ungefähr: Wenn man einen Gott annehme, so müsse er das allervollkommenste Wesen sein. Wenn er das allervollkommenste Wesen ist, dann dürfe ihm nicht das Sein fehlen, die Existenz; denn sonst gäbe es ja ein noch vollkommeneres Wesen, das diejenigen Eigenschaften hätte, die man denkt, und das außerdem existieren würde. Also muß man das vollkommenste Wesen so denken, daß es existiere. Man kann also den Gott gar nicht anders denken als existierend, wenn man ihn als allervollkommenstes Wesen denkt. Das heißt, man kann aus dem Begriffe selbst ableiten, daß es nach dem ontologischen Gottesbeweis den Gott geben muß.

Kant wollte diesen Beweis widerlegen, indem er zu zeigen versuchte, daß man aus einem Begriffe heraus überhaupt nicht die Existenz eines Dinges beweisen kann. Er hat dazu das berühmte Wort geprägt, das ich auch schon öfter angedeutet habe: Hundert wirkliche Taler seien nicht mehr und nicht weniger als hundert mögliche Taler. Das heißt, wenn ein Taler dreihundert Pfennige hat, so müsse man hundert wirkliche Taler zu je dreihundert Pfennigen rechnen, und ebenso müsse man hundert mögliche Taler zu je dreihundert Pfennigen rechnen. Es enthalten also hundert mögliche Taler ebensoviel wie hundert wirkliche Taler; das heißt, es ist kein Unterschied, ob ich hundert wirkliche oder hundert mögliche Taler denke. Daher darf man nicht aus dem bloßen Gedanken des allervollkommensten Wesens die Existenz herausschälen, weil der bloße Gedanke eines möglichen Gottes dieselben Eigenschaften hätte wie der Gedanke eines wirklichen Gottes.

Das erscheint sehr vernünftig. Und seit einem Jahrhundert plagen sich die Menschen herum, wie es mit den hundert möglichen und den hundert wirklichen Talern ist. Nehmen wir aber einen naheliegenden Gesichtspunkt, nämlich den des praktischen Lebens. Kann man von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus sagen, daß hundert wirkliche Taler nicht mehr enthalten als hundert mögliche? Man kann sagen, daß hundert wirkliche Taler just um hundert Taler mehr enthalten als hundert mögliche Taler! Es ist doch ganz klar: Hundert mögliche Taler auf der einen Seite gedacht und hundert wirkliche auf der anderen Seite, das ist ein Unterschied! Es sind auf der anderen Seite gerade hundert Taler mehr. Und auf die hundert wirklichen Taler scheint es doch gerade in den meisten Fällen des Lebens anzukommen.

Aber die Sache hat doch auch einen tieferen Aspekt. Man kann nämlich die Frage stellen: Worauf kommt es denn an bei dem Unterschied von hundert möglichen und hundert wirklichen Talern? Ich denke, es wird jeder zugeben: Für den, der die hundert Taler haben kann, ist zweifellos ein großer Unterschied zwischen hundert möglichen und hundert wirklichen Talern vorhanden. Denn denken Sie sich, Sie brauchen hundert Taler, und jemand stellt Ihnen die Wahl, ob er Ihnen hundert mögliche oder hundert wirkliche Taler geben soll. Wenn Sie sie haben können, scheint es doch auf den Unterschied anzukommen. Aber nehmen Sie an, Sie wären in dem Fall, daß Sie die hundert Taler wirklich nicht haben könnten; dann könnte es sein, daß es für Sie höchst gleichgültig ist, ob Ihnen jemand hundert mögliche oder hundert wirkliche Taler nicht gibt. Wenn man sie nicht haben kann, dann enthalten tatsächlich hundert wirkliche und hundert mögliche Taler ganz gleich viel.

Das hat doch eine Bedeutung. Die Bedeutung hat es nämlich, daß so, wie Kant über den Gott gesprochen hat, nur in einer Zeit gesprochen werden konnte, als man durch menschliche Seelenerfahrung den Gott nicht mehr haben konnte. Als er nicht erreichbar war als eine Wirklichkeit, da war der Begriff des möglichen Gottes oder des wirklichen Gottes gerade so einerlei, wie es einerlei ist, ob man hundert wirkliche Taler oder hundert mögliche Taler nicht haben kann. Wenn es für die Seele keinen Weg gibt zu dem wirklichen Gott, dann führt ganz gewiß auch keine Gedankenentwickelung dazu, die im Stile Kants gehalten ist.

Da sehen Sie, daß die Sache doch auch eine tiefere Seite hat. Ich führe es aber nur an, weil ich dadurch klarmachen wollte, daß, wenn die Frage nach dem Denken kommt, man schon etwas tiefer schürfen muß. Denn Denkfehler schleichen sich durch die erleuchtetsten Geister fort, und man sieht lange nicht ein, worin eigentlich das Brüchige eines solchen Gedankens besteht, wie zum Beispiel des kantischen Gedankens von den hundert möglichen und den hundert wirklichen Talern. Es kommt beim Gedanken auch immer darauf an, daß man die Situation berücksichtigt, in welcher der Gedanke gefaßt wird.

Aus der Natur des allgemeinen Gedankens zuerst und dann aus dem Dasein eines solchen Denkfehlers wie des kantischen im besonderen versuchte ich Ihnen zu zeigen, daß die Wege des Denkens dennoch nicht so ganz ohne Vertiefung in die Dinge betrachtet werden können. Ich will noch von einer dritten Seite aus mich der Sache nähern.

Nehmen wit einmal an, hier wäre ein Berg oder ein Hügel (siehe Zeichnung) und hier sei ein schroffer Abhang (Zeichnung, links). An diesem schroffen Abhange entspringe eine Quelle; die Quelle stürzt senkrecht wie ein richtiger Wasserfall den Abhang hinunter. Unter den ganz gleichen Verhältnissen wie da sei auf der andern Seite auch eine Quelle. Die will ganz dasselbe wie die erstere; aber sie tut es nicht. Sie kann nämlich nicht als Wasserfall hinunterstürzen, sondern rinnt ganz hübsch in Form eines Baches oder Flusses hinunter. - Hat das Wasser andere Kräfte bei der zweiten Quelle als bei der ersten? Ganz offenbar nicht. Denn die zweite Quelle würde ganz dasselbe tun wie die erste, wenn der Berg sie nicht hinderte und nicht seine Kräfte hinaufschicken würde. Sind die Kräfte, die der Berg hinaufschickt, die Haltekräfte, nicht vorhanden, so wird sie wie die erste Quelle hinunterstürzen. Es kommen also zwei Kräfte in Betracht: die Haltekraft des Berges und die Schwerkraft der Erde, vermöge der die eine Quelle hinunterstürzt. Die ist aber bei der anderen Quelle genau ebenso vorhanden, denn man kann sagen: Sie ist da, ich sehe, wie sie die Quelle herunterzieht. Wenn nun jemand ein Skeptiker wäre, so könnte er dies bei der zweiten Quelle leugnen und sagen: Da sieht man zunächst nichts, während bei der ersten Quelle jedes Wasserstäubchen heruntergezogen wird. Man muß also bei der zweiten Quelle in jedem Punkte hinzufügen die Kraft, welche der Schwerkraft entgegenwirkt, die Haltekraft des Berges.

Nehmen wir nun an, es käme jemand und sagte: Was du mir da von der Schwerkraft erzählst, glaube ich nicht recht, und das, was du mir von deiner Haltekraft sagst, glaube ich dir auch nicht. Ist der Berg dort die Ursache, daß die Quelle jenen Weg nimmt? Ich glaube es nicht. - Nun könnte man diesen fragen: Was glaubst du denn dann? - Er könnte antworten: Ich glaube, da unten ist etwas von dem Wasser; gleich darüber ist ebenso etwas von dem Wasser, darüber wieder und so weiter. Ich glaube, daß das Wasser, welches unten ist, von dem Wasser darüber hinuntergestoßen wird, und dieses obere Wasser wird von dem über ihm hinuntergestoßen. Jede darüberliegende Wasserpartie stößt immer die vordere hinunter. Das ist ein beträchtlicher Unterschied. Der erste Mensch behauptet: Die Schwerkraft zieht die Wassermassen herunter. Der zweite dagegen sagt: Das sind Wasserpartien, die schieben immer die unter ihnen liegenden hinunter, und dadurch geht dann das darüberliegende Wasser hinterher.

Nicht wahr, es wäre ein Mensch recht albern, der von einer solchen Schieberei sprechen würde. Aber nehmen wir an, es handle sich nicht um einen Bach oder einen Strom, sondern um die Geschichte der Menschheit, und es würde ein solcher zuletzt Charakterisierter sagen: Das einzige, was ich dir glaube, ist dies: Jetzt leben wir im 20. Jahrhundert, da haben sich gewisse Ereignisse abgespielt; die sind bewirkt von solchen im letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts; diese letzteren sind wieder verursacht von denen im zweiten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts und diese wieder von denen aus dem ersten Drittel. - Das nennt man pragmatische Geschichtsauffassung, wo man in dem Sinne von Ursachen und Wirkungen spricht, daß man immer aus den betreffenden vorhergehenden Ereignissen die folgenden erklärt. So wie jemand die Schwerkraft leugnen und sagen kann, da schiebe bei den Wasserpartien immer jemand nach, so ist es auch, wenn jemand pragmatische Geschichte treibt und den Zustand im 19. Jahrhundert als eine Folge der Französischen Revolution erklärt. Wir freilich sagen: Nein, es sind noch andere Kräfte da außer denen, die da hinten schieben, die überhaupt gar nicht einmal im richtigen Sinne vorhanden sind. Denn geradesowenig wie jene Kräfte beim Bergstrome dahinten schieben, sowenig schieben die dahinterstehenden Ereignisse in der Geschichte der Menschheit; sondern es kommen immer neue Einflüsse aus der geistigen Welt, wie bei der Quelle die Schwerkraft immerfort wirkt; und mit anderen Kräften kreuzen sie sich, wie sich die Schwerkraft bei dem Strom kreuzt mit der Haltekraft des Berges. Wäre nur die eine Kraft vorhanden, dann würdest du sehen, daß die Geschichte ganz anders verläuft. Aber du siehst nicht die einzelnen Kräfte darin. Du siehst nicht das, was physische Weltentwickelung ist, was beschrieben wurde als Folge der Saturn-, Sonnen-, Mond- und Erdenentwickelung; und du siehst nicht das, was fortwährend mit den Menschenseelen vorgeht, welche die geistige Welt durchleben und wieder herunterkommen, was aus den geistigen Welten immer wieder in diese Entwickelung hereinkommt. Das leugnest du einfach.

Aber wir haben eine solche Geschichtsauffassung, die sich ausnimmt, wie wenn jemand mit solchen eben charakterisierten Anschauungen kommen würde, und sie ist nicht so besonders selten. Sie wurde sogar im 19. Jahrhundert als ungeheuer geistreich aufgefaßt. Was würden wir aber dazu sagen können von dem eben gewonnenen Gesichtspunkte aus? Wenn jemand von dem Bergstrome dasselbe behauptete wie von der Geschichte, so würde er einen absoluten Unsinn behaupten. Was liegt denn aber da vor, daß er denselben Unsinn behauptet in bezug auf die Geschichte? - Die Geschichte ist so kompliziert, daß man nicht merkt, daß sie als pragmatische Geschichte fast überall so vorgetragen wird; man merkt es nur nicht.

Wir sehen daraus, daß allerdings die Geisteswissenschaft, welche für die Auffassung des Lebens gesunde Prinzipien zu gewinnen hat, auf den mannigfaltigen Gebieten des Lebens etwas zu tun hat; daß tatsächlich eine gewisse Notwendigkeit besteht, das Denken erst zu lernen, sich erst bekanntzumachen mit den inneren Gesetzen und Impulsen des Denkens. Sonst kann einem nämlich allerlei Groteskes passieren. So zum Beispiel holpert, stolpert, humpelt einer gerade an dem Problem Denken und Sprache heute daher. Das ist der berühmte Sprachkritiker Fritz Mauthner, der jetzt auch ein großes philosophisches Wörterbuch geschrieben hat. Die dicke Mauthnersche «Kritik der Sprache» hat jetzt schon die zweite Auflage erlebt; es ist also ein berühmtes Buch für unsere Zeitgenossen geworden. Viel Geistreiches ist in diesem Buche enthalten, aber auch schreckliche Dinge. So zum Beispiel kann man darin den kuriosen Denkfehler finden - und man stolpert fast nach jeder fünften Zeile über einen solchen Denkfehler -, daß der gute Mauthner die Nützlichkeit der Logik anzweifelt. Denn für ihn ist Denken überhaupt nur Sprechen, und dann hat es keinen Sinn, Logik zu treiben, dann treibt man nur Grammatik. Aber außerdem sagt er: Da es also eine Logik mit Recht gar nicht geben kann, so sind also die Logiker alle Toren gewesen. Schön. Und dann sagt er: Im gewöhnlichen Leben entstehen ja aus Schlüssen Urteile und aus Urteilen erst Vorstellungen. So machen es die Menschen. Wozu braucht man dann erst eine Logik, wenn die Menschen es so machen, daß sie aus Schlüssen Urteile, aus Urteilen Vorstellungen entstehen lassen? Wozu brauchen wir da eine Logik? - Es ist das ebenso geistreich, als wenn jemand sagte: Wozu braucht man eine Botanik? Im vorigen Jahr und vor zwei Jahren sind noch immer die Pflanzen gewachsen! — Aber solche Logik findet man bei dem, der die Logik verpönt. Es ist ja begreiflich, daß er sie verpönt. Man findet noch viel merkwürdigere Dinge in diesem sonderbaren Buche, das mit Bezug auf das Verhältnis zwischen Denken und Sprechen nicht zur Klarheit, sondern zur Konfusion kommt.

Ich sagte, daß wir einen Unterbau brauchen für die Dinge, die uns allerdings zu den Höhen geistiger Betrachtung führen sollen. Ein Unterbau, wie er heute ausgeführt worden ist, mag manchem etwas abstrakt erscheinen; aber wir werden ihn brauchen. Und ich denke, ich versuche die Sache doch so leicht zu machen, daß durchsichtig sein kann, worauf es ankommt. Besonders möchte ich Wert darauf legen, daß man schon durch solche einfachen Betrachtungen einen Begriff davon bekommen kann, wo die Grenze liegt zwischen dem Reiche der Geister der Form und dem Reiche der Geister der Bewegung. Daß man aber einen solchen Begriff bekommt, hängt innig damit zusammen, ob man überhaupt allgemeine Gedanken zugeben darf oder ob man nur Vorstellungen oder Begriffe von einzelnen Dingen zugeben darf. Ich sage ausdrücklich: zugeben darf.

Auf diese Voraussetzungen, zu denen ich, weil sie etwas abstrakt sind, nichts weiter hinzufüge, wollen wir morgen weiter aufbauen.

First Lecture

In these four lectures, which I will give to you during our general meeting, I would like to speak about the connection between human beings and the universe from a certain point of view. And I would like to indicate this point of view with the following words.

Human beings experience within themselves what we can call thoughts, and in these thoughts human beings can feel themselves as something immediately active, as something that can survey its own activity. When we look at any external thing, for example a rose or a stone, and we imagine this external thing, someone could rightly say: You can never really know how much of the thing, of the plant, you actually have in the stone or in the rose when you imagine it. You see the rose, its external redness, its form, how it is divided into individual petals; you see the stone with its color, with its various corners, but you must always say to yourself: There may be something else inside that does not appear to you externally. You do not know how much you actually have in your imagination of the stone, of the rose.

But when someone has a thought, it is they themselves who create that thought. One might say that they are present in every fiber of that thought. Therefore, they are a participant in the activity of the entire thought. They know: what is in the thought is what I have thought into the thought, and what I have not thought into the thought cannot be in it. I have an overview of the thought. No one can claim that when I present a thought, there could be as much else in it as there is in a rose or a stone, because I myself have created the thought, I am present in it, and therefore I know what is in it.

Indeed, thought is our most intimate possession. If we find the relationship of thought to the cosmos, to the universe, then we find the relationship of our most intimate possession to the cosmos, to the universe. This promises us that it is truly a fruitful point of view to consider the relationship of human beings to the universe from the perspective of thought. We will therefore pursue this line of thought, and it will lead us to significant heights of anthroposophical contemplation. But today we will have to lay a foundation that may seem somewhat abstract to some of you. In the next few days, however, we will see that we need this foundation and that without it we can only approach the lofty goals we are striving for in these four lectures with a certain superficiality. What has just been said promises us that if human beings adhere to what they have in their thoughts, they can find an intimate relationship between their being and the universe, the cosmos.

However, there is a difficulty when we want to take this point of view, a great difficulty. I do not mean for our consideration, but for the objective facts, there is a great difficulty. And this difficulty consists in the fact that, although it is true that we live in every fiber of our thoughts and therefore must know our thoughts most intimately when we have them, most people have no thoughts! And this is not usually thought through thoroughly, that most people have no thoughts. It is not thought through thoroughly because to do so would require—precisely—thoughts! One thing must first be pointed out. What prevents people from having thoughts in the widest sphere of our lives is that people do not always feel the need to really penetrate to the thought for the ordinary use of life, but instead of thinking, they are content with words. Most of what is called thinking in ordinary life takes place in words. We think in words. We think in words much more than we realize. And when many people ask for an explanation of this or that, they are satisfied with any word that has a familiar sound to them, that reminds them of this or that; and then they take what they feel when they hear such a word as an explanation and believe that they have the thought.

Yes, what I have just said led, at a certain time in the development of human spiritual life, to the emergence of a view which is still held today by many people who call themselves thinkers. In the new edition of my “World and Life Views in the Nineteenth Century,” I have attempted to thoroughly revise this book by prefacing it with a history of the development of Western thought, beginning with the sixth century BC and continuing up to the nineteenth century, and then adding at the end, to what was given when the book first appeared, a presentation of, let us say, the intellectual life of the spirit up to our own day. The content that was already there has also been extensively reworked. I had to show how thought actually arises in a particular age. It really only arises, one might say, around the 6th or 8th century BC. Before that, human souls did not experience what can be called thought in the true sense of the word. What did human souls experience before that? They experienced images. And all experience of the outer world took place in images. I have often said this from certain points of view. This experience of images is the last phase of the old clairvoyant experience. Then, for the human soul, the image passes into thought.

What I intended in this book is to show this result of spiritual science purely by tracing its philosophical development. Remaining entirely on the ground of philosophical science, it is shown that thought was born in ancient Greece, that it arises from the fact that it springs forth for the human soul experience from the ancient symbolic experience of the external world. I then attempted to show how this idea continued in Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, how it took on certain forms, how it developed further, and then led in the Middle Ages to what I now wish to mention.

The development of the idea leads to the doubt as to whether what we call general ideas, general concepts, can exist in the world at all, to so-called nominalism, to the philosophical view that general concepts can only be names, i.e., only words. There was even a philosophical view, which many still hold today, that these general ideas can only be words.

To illustrate what has just been said, let us take a simple and general concept; let us take the concept “triangle” as a general concept. Now, someone who comes along with their nominalist point of view, who cannot get away from what developed as nominalism in this regard in the 11th to 13th centuries, will say something like this: Draw me a triangle! — Fine, I will draw him a triangle, for example, one like this:

Fine, he says, that is a special triangle with three acute angles; it exists. But I will draw you another one. — And he draws a triangle with a right angle and another with a so-called obtuse angle.

So now we call the first one an acute-angled triangle, the second one a right-angled triangle, and the third one an obtuse-angled triangle. The person says: I believe you, there is an acute-angled triangle, a right-angled triangle, and an obtuse-angled triangle. But that's not what a triangle is. A general triangle must contain everything that a triangle can contain. The first, second, and third triangles must fall under the general concept of a triangle. However, a triangle that is acute-angled cannot be right-angled and obtuse-angled at the same time. An acute-angled triangle is a special triangle, not a general triangle; similarly, a right-angled and obtuse-angled triangle are special triangles. However, there cannot be a general triangle. Therefore, the general triangle is a word that summarizes the special triangles. But there is no general concept of the triangle. It is a word that summarizes the details.

This can of course be taken further. Let us assume that someone utters the word lion. Now, someone who takes the nominalist point of view says: There is a lion in Berlin Zoo, there is also a lion in Hanover Zoo, and there is also one in Munich Zoo. The individual lions exist; but there is no general lion that has anything to do with the lions in Berlin, Hanover, and Munich. It is merely a word that summarizes the individual lions. There are only individual things, and apart from the individual things, says the nominalist, there is nothing but words that summarize the individual things.

This view, as I said, has come up; it is still held today by astute logicians. And anyone who thinks about the matter that has just been discussed will have to admit that there is something special about it; I cannot readily conclude whether there really is such a thing as “the lion in general” and “the triangle in general,” because I cannot see it clearly. If someone were to come along and say: Look, my friend, I cannot accept your showing me the Munich, Hanover, or Berlin lion. If you claim that the lion “in general” exists, you must take me somewhere where the “lion in general” exists. But if you show me the Munich, Hanover, and Berlin lions, you have not proven to me that the “lion in general” exists. If someone came along who held this view and you were asked to show them the “lion in general,” you would initially be at a loss. It is not so easy to answer the question of where to take the person concerned to show them “lions in general.”

Now, let us not go into what spiritual science has to offer; that will come later. Let us stick with thinking for now, let us stick with what can be achieved through thinking, and we will have to say to ourselves: If we want to remain on this ground, it is not right to lead any skeptic to the “lion in general.” That really is not possible. Here lies one of the difficulties that must simply be admitted. For if one does not want to admit this difficulty in the realm of ordinary thinking, then one does not allow oneself to engage with the difficulty of human thinking in general.

Let us stick with the triangle; for ultimately it is irrelevant to the general case whether we clarify the matter using the triangle, the lion, or something else. At first glance, it seems futile to draw a general triangle that contains all the properties of all triangles. And because it not only appears hopeless, but also is hopeless for ordinary human thinking, all external philosophy stands at a crossroads here, and its task would be to admit once and for all that it stands at a crossroads as external philosophy. But this boundary is only that of external philosophy. There is a way to cross this boundary, and we will now familiarize ourselves with this possibility.

Let's imagine that we don't just draw the triangle and say: Now I've drawn you a triangle, and there it is. Someone will always be able to object: That's just an acute-angled triangle, it's not a general triangle. You can draw a triangle in other ways. Actually, you can't, but we'll see in a moment how this ability and inability relate to each other. Let's assume that we draw this triangle here and allow each side to move in any direction it wants. And we allow it to move at different speeds (speaking while drawing on the board):

This side moves so that in the next moment it takes this position, this one so that in the next moment it takes this position. This one moves much slower, this one moves faster, and so on. Now the direction reverses

In short, we enter into the uncomfortable idea that we say: I don't just want to draw a triangle and leave it there, but I make certain demands on your imagination. You must imagine that the sides of the triangle are constantly in motion. If they are in motion, then a right-angled or an obtuse-angled triangle or any other shape can emerge simultaneously from the form of the movements.

Two things can be done and demanded in this area. The first thing that can be demanded is that it should be nice and convenient. When someone draws a triangle, it is finished, and you know what it looks like; now you can rest comfortably in your thoughts, because you have what you want. But you can also do the other thing: consider the triangle as a starting point, as it were, and allow each side to rotate at different speeds and in different directions. In this case, however, you are not so comfortable, but you have to carry out movements in your thoughts. But in return, you really have the general idea of a triangle in there; it just cannot be achieved if you want to conclude with a triangle. The general idea of a triangle is there when you have the idea in constant motion, when it is versatile.

Because philosophers have not done what I have just said, namely to set thoughts in motion, they necessarily stand at a crossroads and justify nominalism. Now let us translate what I have just said into a language familiar to us, into a language we have known for a long time.

When we are required to ascend from the particular thought to the general thought, we must set the particular thought in motion so that the thought in motion is the general thought that slips from one form into another. I say form; correctly thought, it is: the whole moves, and each individual thing that emerges from the movement is a self-contained form. Previously, I only drew individual forms, an acute-angled triangle, a right-angled triangle, and an obtuse-angled triangle. Now I draw something—I don't actually draw it, as I already said, but you can imagine it—which is supposed to evoke the idea that the general thought is in motion and that the individual form is produced by its standing still—“the form produces,” I say.

Here we see that the philosophers of nominalism, who necessarily stand at a boundary, move in a certain realm, the realm of the spirits of form. Within the realm of the spirits of form that surrounds us, forms reign supreme; and because forms reign supreme, this realm contains individual, strictly self-contained individual things. From this you can see that the philosophers I am referring to have never made the decision to leave the realm of forms, and therefore can have nothing in general ideas but words, mere words. If they were to leave the realm of particular things, that is, of forms, they would enter into a realm of imagination that is in constant motion; that is, they would have in their thinking a representation of the realm of spirits of motion, the next higher hierarchy. But most philosophers are not prepared to do this. And when one person in the last period of Western thought did allow himself to think in this sense, he was little understood, although much is said and rambled about him. Look up what Goethe wrote in his “Metamorphosis of Plants” about what he called the “primordial plant”; then look up what he called the “primordial animal,” and you will find that you can only make sense of these concepts of “primordial plant” and “primordial animal” if you think of them as mobile. If one takes up this flexibility of which Goethe himself speaks, then one does not have a closed concept limited in its forms, but one has that which lives in its forms, that which creeps through the entire development of the animal kingdom or the plant kingdom, that which changes in this creeping just as the triangle changes into an acute-angled or an obtuse-angled triangle, and that which can soon be a “wolf” and “lion,” and soon “beetle,” depending on how the mobility is arranged so that the characteristics change as they pass through the details. Goethe set the rigid concepts of forms in motion. That was his great, central achievement. That was the significant thing he introduced into the observation of nature in his time.