Human and Cosmic Thought

GA 151

22 January 1914, Dornach

Lecture III

Yesterday I tried to set forth those world-outlooks which are possible for man; so possible that certain valid proofs can be produced for the correctness of each of them in a certain realm. For anyone who is not concerned to weld together into a single system all that he has been in a position to observe and reflect upon in a certain limited domain, and then sets out to seek proofs for it, but who wants to penetrate into the truth of the world, it is important to realize that broad-mindedness is necessary because twelve typical varieties of world-outlook are actually possible for the mind of man. (For the moment we need not go into the transitional ones.) If one wants to come really to the truth, then one must try clearly to understand the significance of these twelve typical varieties, must endeavour to recognize for what domain of existence one or other variety holds the best key. If we let these twelve varieties pass once again before our mind's eye, as we did yesterday, then we find that they are: Materialism, Sensationalism, Phenomenalism, Realism, Dynamism, Monadism, Spiritism, Pneumatism, Psychism, Idealism, Rationalism and Mathematism.

Now in the actual field of human searching after truth it is unfortunate that individual minds, individual personalities, always incline to let one or the other of these varieties have the upper hand, with the result that different epochs develop one-sided outlooks which then work back on the people living at that time.

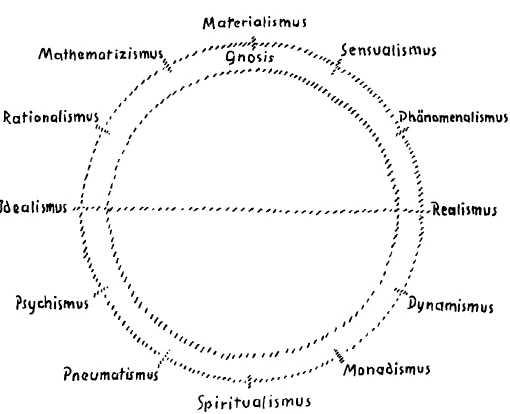

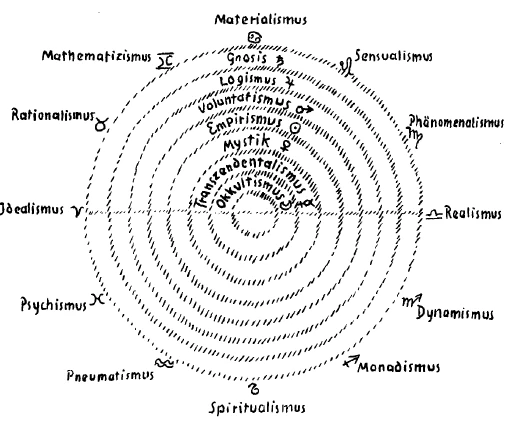

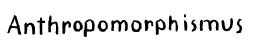

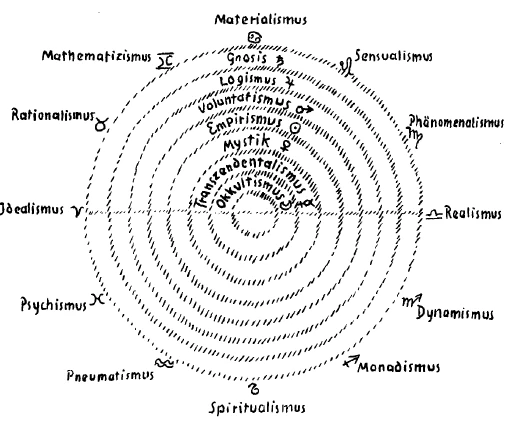

We had better arrange the twelve world-outlooks in the form of a circle (see Diagram 11), and quietly observe them. They are possible, and one must know them. They really stand in such a relation to one another that they form a mental copy of the Zodiac with which we are now so well acquainted. As the sun apparently passes through the Zodiac, and as other planets apparently do the same, so it is possible for the human soul to pass through a mental circle which embraces twelve world-pictures. Indeed, one can even bring the characteristics of these pictures into connection with the individual signs of the Zodiac, and this is in no wise arbitrary, for between the individual signs of the Zodiac and the Earth there really is a connection similar to that between the twelve world-outlooks and the human soul. I mean this in the following sense.

We could not say that there is an easily understandable relation between, e.g. the sign Aries and the Earth. But when the Sun, Saturn, or Mercury are so placed that from the Earth they are seen in the sign Aries, then influence is different from what it is when they are seen in the sign Leo. Thus the effect which comes to us out of the Cosmos from the different planets varies according as the individual planets stand in one or other of the Zodiacal signs. In the case of the human soul, it is even easier to recognize the effects of these twelve “mental-zodiacal-signs” (Geistes-Tierkreisbilder). There are souls who have the tendency to receive a given influence on their inner life, on their scientific, philosophic or other mental proclivities, so that their souls are open to be illuminated, as it were, by Idealism. Other souls are open to be shone upon by Materialism, others by Sensationalism. A man is not a Sensationalist, Materialist, Spiritist or Pneumatist because this or that world-outlook is—and can be seen to be—correct, but because his soul is so conditioned that it is predominantly influenced by the respective mental-zodiacal-sign. Thus in the twelve mental-zodiacal-signs we have something that can lead us to a deep insight into the way in which human world-outlooks arise, and can help us to see far into the reasons why, on the one hand, men dispute about world-outlooks, and why, on the other hand, they ought not to dispute but would do much better to understand why it happens that people have different world-outlooks. How, in spite of this, it may be necessary for certain epochs strongly to oppose the trend of this or the other world-outlook, we shall have to explain the next lecture. What I have said so far refers to the moulding of human thought by the spiritual cosmos of the twelve zodiacal signs, which form as it were our spiritual horizon.

But there is still something else that determines human world-outlooks. You will best understand this if I first of all show you the following.

A man can be so attuned in his soul—for the present it is immaterial by which of these twelve “mental-zodiacal signs” his soul is illuminated—that the soul-mood expressed in the whole configuration of his world-outlook can be designated as Gnosis. A man is a Gnostic when his disposition is such that he gets to know the things of the world not through the senses, but through certain cognitional forces in the soul itself. A man can be a Gnostic and at the same time have a certain inclination to be illuminated by e.g. the mental-zodiacal-sign that we have here called “Spiritism”. Then his Gnosticism will have a deeply illuminated insight into the relationships of the spiritual worlds. But a man can also be, e.g. a Gnostic of Idealism; then he will have a special proclivity for seeing clearly the ideals of mankind and the ideas of the world. Thus there can be a difference between two men who are both Idealists. One man will be an idealistic enthusiast who always has the word “ideal”, “ideal”, “ideal”, on his lips, but does not know much about idealism; he lacks the faculty for conjuring up ideals in sharp outline before his inner sight. The other man not only speaks of Idealism, but knows how to picture the ideals clearly in his soul. The latter, who inwardly grasps Idealism quite concretely—as intensely as a man grasps external things with his hand—is a Gnostic in the domain of Idealism. Thus one could say that he is basically a Gnostic, but is specially illuminated by the mental-zodiacal-sign of Idealism.

There are also persons who are specially illuminated by the world-outlook sign of Realism. They go through the world in such a way that their whole mode of perceiving and encountering the world enables them to say much, very much, to others about the world. They are neither Spiritists nor Idealists; they are quite ordinary Realists. They are equipped to have really fine perceptions of the external reality around them, and of the intrinsic qualities of things. They are Gnostics, genuine Gnostics, only they are Gnostics of Realism. There are such Gnostics of Realism, and Spiritists or Idealists are often not Gnostics of Realism at all. We can indeed find that people who call themselves good Theosophists may go through a picture-gallery and understand nothing about it, whereas others who are not Theosophists at all, but are Gnostics of Realism, are able to make an abundance of significant comments on it, because with their whole personality they are in touch with the reality of the things they see. Or again, many Theosophists go out into the country and are unable to grasp with their whole souls anything of the greatness and sublimity of nature; they are not Gnostics of Realism.

There are also Gnostics of Materialism. Certainly they are strange Gnostics. But quite in the sense in which there are Gnostics of Realism, there can be Gnostics of Materialism. They are persons who have feeling and perception only for all that is material; persons who try to get to know what the material is by coming into direct contact with it, like the dog who sniffs at substances and tries to get to know them intimately in that way, and who really is, in regard to material things, an excellent Gnostic. One can be a Gnostic in connection with all twelve world-outlook signs. Hence, if we want to put Gnosis in its right place, we must draw a circle, and the whole circle signifies that the Gnosis can move round through all twelve world-outlook signs. Just as a planet goes through all twelve signs of the Zodiac, so can the Gnosis pass through the twelve world-outlook signs. Certainly, the Gnosis will render the greatest service for the healing of souls when the Gnostic frame of mind is applied to Spiritism. One might say that Gnosis is thoroughly at home in Spiritism. That is its true home. In the other world-outlook-signs it is outside its home. Logically speaking, one is not justified in saying that there could not be a materialistic Gnosis. The pedants of concepts and ideas can settle such knotty points more easily than the sound logicians, who have a somewhat more complicated task. One might say, for example: “I will call nothing ‘Gnosis’ except what penetrates into the ‘spirit’.” That is an arbitrary attitude with regard to concepts; as arbitrary as if one were to say, “So far I have seen violets only in Austria; therefore I call violets only flowers that grow in Austria and have a violet colour—nothing else.” Logically it is just as impossible to say that there is Gnosis only in the world-outlook-sign of Spiritism; for Gnosis is a “planet” which passes through all the mental-constellations.

There is another world-outlook-mood. Here I speak of “mood”, whereas otherwise I speak of “signs” or “pictures”. Of late it has been thought that one could more easily become acquainted—and yet here even the easy is difficult—with this second mood, because its representative, in the constellation of Idealism, is Hegel. But this special mood in which Hegel looks at the world need not be in the constellation of Idealism, for it, too, can pass through all the constellations. It is the world-outlook of Logicism. The special mark of Logicism consists in its enabling the soul to connect thoughts, concepts and ideas with one another. As when in looking at an organism one comes from the eyes to the nose and the mouth and regards them as all belonging to each other, so Hegel arranges all the concepts that he can lay hold of into a great concept-organism—a logical concept-organism. Hegel was simply able to seek out everything in the world that can be found as thought, to link together thought with thought, and to make an organism of it—Logicism! One can develop Logicism in the constellation of Idealism, as Hegel did; one can develop it, as Fichte did, in the constellation of Psychism; and one can develop it in other constellations. Logicism is again something that passes like a planet through the twelve zodiacal signs.

There is a third mood of the soul, expressed in world-outlooks; we can study this in Schopenhauer, for example. Whereas the soul of Hegel when he looked out upon the world was so attuned that with him everything conceptual takes the form of Logicism, Schopenhauer lays hold of everything in the soul that pertains to the character of will. The forces of nature, the hardness of a stone, have this character for him; the whole of reality is a manifestation of will. This arises from the particular disposition of his soul. This outlook can once more be regarded as a planet which passes through all twelve zodiacal signs. I will call this world-outlook, Voluntarism.

Schopenhauer was a voluntarist, and in his soul he was so constituted that he laid himself open to the influence of the mental constellation of Psychism. Thus arose the peculiar Schopenhauerian metaphysics of the will: Voluntarism in the mental constellation of Psychism.

Let us suppose that someone is a Voluntarist, with a special inclination towards the constellation of Monadism. Then he would not, like Schopenhauer, take as basis of the universe a unified soul which is really “will”; he would take many “monads”, which are, however, will-entities. This world of monadic voluntarism as been developed most beautifully, ingeniously, and I might say, in the most inward manner, by the Austrian philosophic poet, Hamerling. Whence came the peculiar teaching that you find in Hamerling's Atomistics of the Will? It arose because his soul was attuned to Voluntarism, while he came under the mental constellation of Monadism. If we had the time, we could mention examples for each soul-mood in each constellation. They are to be found in the world.

Another special mood is not at all prone to ponder whether behind the phenomena there is still this or that, as is done by the Gnostic mood, or the idealistic or voluntary moods, but which simply says: “I will incorporate into my world-conception whatever I meet with in the world, whatever shows itself to me externally.” One can do this in all domains—i.e. through all mental constellations. One can do it as a materialist who accepts only what he encounters externally; one can also do it as Spiritist. A man who has this mood will not trouble himself to seek for a special connection behind the phenomena; he lets things approach and waits for whatever comes from them. This mood we can call Empiricism. Empiricism signifies a soul-mood which simply accepts whatever experience may offer. Through all twelve constellations one can be an empiricist, a man with a world-conception based on experience. Empiricism is the fourth psychic mood which can go through all twelve constellations.

One can equally well develop a mood which is not satisfied with immediate experience, as in Empiricism, so that one feels through and through, as an inner necessity, a mood which says: Man is placed in the world; in his soul he experiences something about the world that he cannot experience externally; only there, in that inner realm, does the world unveil its secrets. One may look all round about and yet see nothing of the mysteries which the world includes. Someone imbued with a mood of this kind can often say: “Of what help to me is the Gnosis that takes pains to struggle up to a kind of vision? The things of the external world that one can look upon—they cannot show me the truth. How does Logicism help me to a world-picture? ... In Logicism the nature of the world does not express itself. What help is there in speculations about the will? It merely leads us away from looking into the depths of our own soul, and into those depths one does not look when the soul wills, but, on the contrary, just when by surrendering itself it is without will.” Voluntarism, therefore, is not the mood that I mean here, neither is Empiricism—the mere looking upon and listening to experience and events. But when the soul has become quiet and seeks inwardly for the divine Light, this soul-mood can be called Mysticism.

Again, one can be a mystic through all the twelve mental constellations. It would certainly not be specially favourable if one were a mystic of materialism—i.e. if one experienced inwardly not the mental, the spiritual, but the material. For a mystic of materialism is really he who has acquired a specially fine perception of how one feels when one enjoys this or that substance. It is somewhat different if one imbibes the juice of this plant or the other, and then waits to see what happens to one's organism. One thus grows together with matter in one's experience; one becomes a mystic of matter. This can even become an “awakening” for life, so that one follows up how one substance or another, drawn from this or that plant, works upon the organism, affecting particularly this or that organ. And so to be a Mystic of Materialism is a precondition for investigating individual substances in respect of their healing powers.

One can be a Mystic of the world of matter, and one can be a Mystic of Idealism. An ordinary Idealist or Gnostic Idealist is not a Mystic of Idealism. A Mystic of Idealism is one who has above all the possibility in his own soul of bringing out from its hidden sources the ideals of humanity, of feeling them as something divine, and of placing them in that light before the soul. We have an example of the Mystic of Idealism in Meister Eckhardt.

Now the soul may be so attuned that it cannot become aware of what may arise from within itself and appear as the real inner solution of the riddle of the universe. Such a soul may, rather, be so attuned that it will say to itself: “Yes, in the world there is something behind all things, also behind my own personality and being, so far as I perceive this being. But I cannot be a mystic. The mystic believes that this something behind flows into his soul. I do not feel it flow into my soul; I only feel it must be there, outside.” In this mood, a person presupposes that outside his soul, and beyond anything his soul can experience, the essential being of things lies hidden; but he does not suppose that this essential nature of things can flow into his soul, as does the Mystic. A person who takes this standpoint is a Transcendentalist—perhaps that is the best word for it. He accepts that the essence of a thing is transcendent, but that it does not enter into the soul—hence Transcendentalism. The Transcendentalist has the feeling: “When I perceive things, their nature approaches me; but I do not perceive it. It hides behind, but it approaches me.”

Now it is possible for a man, given all his perceptions and powers of cognition, to thrust away the nature of things still further than the Transcendentalist does. He can say; “The essential nature of things is beyond the range of ordinary human knowledge.” The Transcendentalist says; “If with your eyes you see red and blue, then the essential being of the thing is not in the red or blue, but lies hidden behind it. You must use your eyes; then you can get to the essential being of the thing. It lies behind.” But the mood I now have in mind will not accept Transcendentalism. On the contrary, it says: “One may experience red or blue, or this or that sound, ever so intensely; nothing of this expresses the hidden being of the thing. My perception never makes contact with this hidden being.” Anyone who speaks in this way speaks very much as we do when we take the standpoint that in external sense-appearance, in Maya, the essential nature of things does not find expression. We should be Transcendentalists if we said: “The world is spread out all around us, and this world everywhere proclaims its essential being.” This we do not say. We say: “This world is Maya, and one must seek the inner being of things by another way than through external sense-perception and the ordinary means of cognition.” Occultism! The psychic mood of Occultism!

Again, one can be an Occultist throughout all the mental-zodiacal signs. One can even be a thorough Occultist of Materialism. Yes, the rationally-minded scientists of the present day are all occultists of materialism, for they talk of “atoms”. But if they are not irrational it will never occur to them to declare that with any kind of “method” one can come to the atom. The atom remains in the occult. It is only that they do not like to be called “Occultists”, but they are so in the fullest sense of the word.

Apart from the seven world-outlooks I have drawn here, there can be no others—only transitions from one to another. Thus we must not only distinguish twelve various shades of world-outlook which are at rest round the circle, so to speak, but we must recognize that in each of the shades a quite special mood of the human soul is possible. From this you can see how immensely varied are the outlooks open to human personalities. One can specially cultivate each of these seven world-outlook-moods, and each of them can exist on one or other shade.

What I have just depicted is actually the spiritual correlative of what we find externally in the world as the relations between the signs of the Zodiac and the planets, the seven planets familiar in Spiritual Science. Thus we have an external picture (not invented, but standing out there in the cosmos) for the relations of our seven world-outlook-moods to our twelve shades of world-outlook. We shall have the right feeling for this picture if we contemplate it in the following manner.

Let us begin with Idealism, and let us mark it with the mental-zodiacal sign of Aries; in like manner let us mark Rationalism as Taurus, Mathematism as Gemini, Materialism as Cancer, Sensationalism as Leo, Phenomenalism as Virgo, Realism as Libra, Dynamism as Scorpio, Monadism as Sagittarius, Spiritism as Capricorn, Pneumatism as Aquarius, and Psychism as Pisces. The relations which exist spatially between the individual zodiacal signs are actually present between these shades of world-outlook in the realm of spirit. And the relations which are entered into by the planets, as they follow their orbits through the Zodiac, correspond to the relations which the seven world-outlook-moods enter into, so that we can feel Gnosticism as Saturn, Logicism as Jupiter, Voluntarism as Mars, Empiricism as Sun, Mysticism as Venus, Transcendentalism as Mercury, and Occultism as Moon (see Diagram 11).

Even in the external pictures—although the main thing is that the innermost connections correspond—you will find something similar. The Moon remains occult, invisible when it is New Moon; it must have the light of the Sun brought to it, just as occult things remain occult until, through meditation, concentration and so on, the powers of the soul rise up and illuminate them. A person who goes through the world and relies only on the Sun, who accepts only what the Sun illuminates, is an Empiricist. A person who reflects on what the Sun illuminates, and retains the thoughts after the Sun has set, is no longer an Empiricist, because he no longer depends upon the Sun. “Sun” is the symbol of Empiricism. I might take all this further but we have only four periods to spend on this important subject, and for the present I must leave you to look for more exact connections, either throughout your own thinking or through other investigations. The connections are not difficult to find when the model has been given.

Broadmindedness is all too seldom sought. Anyone really in earnest about truth would have to be able to represent the twelve shades of world-outlook in his soul. He would have to know in terms of his own experience what it means to be a Gnostic, a Logician, a Voluntarist, an Empiricist, a Mystic, a Transcendentalist, an Occultist. All this must be gone through experimentally by anyone who wants to penetrate into the secrets of the universe according to the ideas of Spiritual Science. Even if what you will find in the book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds, does not exactly fit in with this account, it is really depicted only from other points of view, and can lead us into the single moods which are here designated as the Gnostic mood, the Jupiter mood, and so on.

Often a man is so one-sided that he lets himself be influenced by only one constellation, by one mood. We find this particularly in great men. Thus, for example, Hamerling is an out-and-out Monadist or a monadologistic Voluntarist; Schopenhauer is a pronounced voluntaristic Psychist. It is precisely great men who have so adjusted their souls that their world-outlook-mood stands in a definite spiritual constellation. Other people get on much more easily with the different standpoints, as they are called. But it can also happen that men are stimulated from various sides in reaching their world-outlook, or for what they place before themselves as world-outlook. Thus someone may be a good Logician, but his logical mood stands in the constellation of Sensationalism; he can at the same time be a good Empiricist, but his empirical mood stands in the constellation of Mathematism. This may happen. When it does happen, a quite definite world-outlook is produced. Just at the present time we have an example of the outlook that comes about through someone having his Sun—in spiritual sense—in Gemini, and his Jupiter in Leo; such a man is Wundt. And all the details in the philosophical writings of Wundt can be grasped when the secret of his special psychic configuration has been penetrated.

The effect is specially good when a person has experienced, by way of exercises, the various psychic moods—Occultism, Transcendentalism, Mysticism, Empiricism, Voluntarism, Logicism, Gnosis—so that he can conjure them up in his mind and feel all their effects at once, and can then place all these moods together in the constellation of Phenomenalism, in Virgo. Then there actually comes before him as phenomena, and with a quite special magnificence, that which can be unveiled for him in a remarkable way as the content of his world-picture. When, in the same way, the individual world-outlook-moods are brought one after another in relation to another constellation, then it is not so good. Hence in many ancient Mystery-schools, just this mood, with all the soul-planets standing in the spiritual constellation of Virgo, was induced in the pupils because it was through this that they could most easily fathom the world. They grasped the phenomena, but they grasped them “gnostically”. They were in a position to pass behind the thought-phenomena, but they had no crude experience of the will: that would happen only if the soul-mood of Voluntarism were placed in Scorpio. In short, by means of the constellation given through the world-outlook-moods—the planetary element—and through the nuances connected with the spiritual Zodiac, the world-picture which a person carries with him through a given incarnation is called forth.

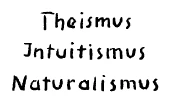

But there is one more thing. These world-pictures—they have many nuances if you reckon with all their combinations—are modified yet again by possessing quite definite tones. But we have only three tones to distinguish. All world-pictures, all combinations which arise in this manner, can appear in one of three ways. First, they can be theistic, so that what appears in the soul as tone must be called Theism. Or, in contrast to Theism, there may be a soul-tone that we must call Intuitionism. Theism arises when a person clings to all that is external in order to find his God, when he seeks his God in the external. The ancient Hebrew Monotheism was a particularly “theistic” world-outlook. Intuitionism arises when a person seeks his world-picture especially through intuitive flashes from his inner depths. And there is a third tone, Naturalism.

These three psychic tones are reflected in the cosmos, and their relation to one another in the soul of man is exactly like that of Sun, Moon and Earth, so that Theism corresponds to the Sun—the Sun being here considered as a fixed star—Intuitionism to the Moon, and Naturalism to the Earth. If we transpose the entities here designated as Sun, Moon and Earth into the spiritual, then a man who goes beyond the phenomena of the world and says: “When I look around, then God, Who fills the world, reveals Himself to me in everything,” or a man who stands up when he comes into the rays of the sun—they are Theists. A man who is content to study the details of natural phenomena, without going beyond them, and equally a man who pays no attention to the sun but only to its effects on the earth—he is a Naturalist. A man who seeks for the best, guided by his intuitions—he is like the intuitive poet whose soul is stirred by the mild silvery glance of the moon to sing its praises. Just as one can bring moonlight into connection with imagination, so the occultist, the Intuitionist, as we mean him here, must be brought into relation with the moon.

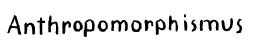

Lastly there is a special thing. It occurs only in a single case, when a person, taking all the world-pictures to some extent, restricts himself only to what he can experience on or around or in himself. That is Anthropomorphism. Such a person corresponds to the man who observes the Earth on its own account, independently of its being shone upon by the Sun, the Moon, or anything else. Just as we can consider the Earth for itself alone, so also with regard to world-outlooks we can reckon only with what as men we can find in ourselves. So does a widespread Anthropomorphism arise in the world. If one goes out beyond man in himself, as one must go out to Sun and Moon for an explanation of the phenomenon of the Earth—something that present-day science does not do—then one comes to recognize three different things, Theism, Intuitionism and Naturalism side by side and each with its justification. For it is not by insisting on one of these tones, but by letting them sound together, that one arrives at the truth. And just as our intimate corporeal relation with Sun, Moon and Earth is placed in the midst of the seven planets, so Anthropomorphism is the world-outlook nearest to the harmony that can sound forth from Theism, Intuitionism and Naturalism, while this harmony again is closest to the conjoined effect of the seven psychic moods; and these seven moods are shaded according to the twelve signs of the Zodiac.

You see, it is not true to talk in terms of one cosmic conception, but of \(12 + 7 = 19 + 3 = 22 + 1 = 23\) cosmic conceptions which all have their justification. We have twenty-three legitimate names for cosmic conceptions. But all the rest can arise from the fact that the corresponding planets pass through the twelve spiritual signs of the encircling Zodiac. And now try, from what has been explained, to enter into the task confronting Spiritual Science: the task of acting as peacemaker among the various world-outlooks. The way to peace is to realize that the world-outlooks conjointly, in their reciprocal action on one another, can be in a certain sense explained, but that they cannot lead into the inner nature of truth if they remain one-sided. One must experience in oneself the truth-value of the different world-outlooks, in order—if one may say so—to be in agreement with truth. Just as you can picture to yourselves the physical cosmos; the Zodiac, the planetary system; Sun, Moon and Earth (the three together) and the Earth on its own account, so you can think of a spiritual universe: Anthropomorphism; Theism, Intuitionism, Naturalism; Gnosis, Logicism, Voluntarism, Empiricism, Mysticism, Transcendentalism, Occultism, and all this moving round through the twelve spiritual Zodiacal signs. All this does exist, only it exists spiritually. As truly as the physical cosmos exists physically, so truly does this other universe exist spiritually.

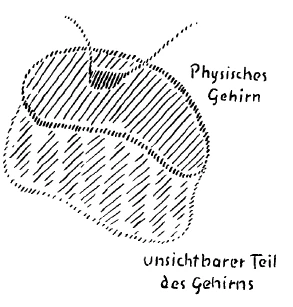

In that half of the brain which is found by the anatomist, and of which one may say that it is shaped like a half-hemisphere, those activities of the spiritual cosmos which proceed from the upper nuances are specially operative. On the other hand, there is a part of the brain which is visible only when one observes the etheric body; and this is specially influenced by the lower part of the spiritual cosmos. (see Diagram 9 and Diagram 11.) But how is it with this influencing? Let us say of someone that with his Logicism he is placed in Sensationalism, and that with his Empiricism he is placed in Mathematism. The resulting forces then work into his brain, so that the upper part of his brain is specially active and dominates the rest. Countless varieties of brain-activity arise from the fact that the brain swims, as it were, in the spiritual cosmos, and its forces work into the brain in the way we have been able to describe. The brains of men are as varied in kind as all the possible combinations that can spring from this spiritual cosmos. The lower part of the spiritual cosmos does not act on the physical brain at all, but on the etheric brain.

The best impression one can retain from the whole subject would lead one to say: It opens out for me a feeling for the immensity of the world, for the qualitatively sublime in the world, for the possibility that man can exist in endless variety in this world. Truly, if we consider only this, we can already say to ourselves: There is no lack of varied possibilities open to us for the different incarnations that we have to go through on earth. And one can also feel sure that anyone who looks at the world in this light will be impelled to say: “Ah, how grand, how rich, the world is! What happiness it is to go on and on taking part, in ways ever more varied, in its existence, its activities, its endeavours!”

Dritter Vortrag

Ich habe gestern diejenigen Weltanschauungsnuancen darzustellen versucht, welche dem Menschen möglich sind, so möglich, daß für jede dieser Weltanschauungsnuancen gewisse vollgültige Beweise der Richtigkeit, der Wahrheit für ein gewisses Gebiet erbracht werden können. Für den, der nicht darauf aus ist, alles, was er auf einem bestimmten engbegrenzten Gebiete zu beobachten, zu überdenken in der Lage war, zu einem Begriffssystem zusammenzuschmieden und dann die Beweise dafür zu suchen, sondern für den, der darauf aus ist, wirklich in die Wahrheit der Welt einzudringen, ist es wichtig zu wissen, daß diese Allseitigkeit notwendig ist, die sich darin ausspricht, daß dem menschlichen Geist wirklich zwölf typische Weltanschauungsnuancen - auf die Übergänge dazwischen kommt es jetzt nicht an - möglich sind. Will man wirklich zur Wahrheit kommen, dann muß man den Versuch machen, sich die Bedeutung dieser Weltanschauungsnuancen einmal klarzumachen, muß den Versuch machen, zu erkennen, auf welchen Gebieten des Daseins die eine oder die andere dieser Weltanschauungsnuancen den besseren Schlüssel bildet. Wenn wir uns noch einmal diese zwölf Weltanschauungsnuancen vor Augen führen, wie das gestern geschehen ist, so ist es also der Materialismus, der Sensualismus, der Phänomenalismus, der Realismus, der Dynamismus, der Monadismus, der Spiritualismus, der Pneumatismus, der Psychismus, der Idealismus, der Rationalismus und der Mathematizismus.

Es ist nun in der wirklichen Welt des menschlichen Forschungsstrebens nach der Wahrheit leider so, daß bei den einzelnen Geistern, bei den einzelnen Persönlichkeiten immer die Hinneigung zu der einen oder der anderen dieser Weltanschauungsnuancen überwiegt und daß dadurch die Einseitigkeiten in den verschiedenen Weltanschauungen der verschiedenen Epochen auf die Menschen wieder wirken. Was ich so als die zwölf Hauptweltanschauungen hingestellt habe, das muß man kennen als etwas, was man wirklich so überschaut, daß man gleichsam immer die eine Weltanschauung neben die andere so kreisförmig hinstellt und sie als ruhend betrachtet. Sie sind möglich; man muß sie kennen. Sie verhalten sich wirklich so, daß sie ein geistiges Abbild des uns ja wohlbekannten Tierkreises sind. Wie den Tierkreis scheinbar die Sonne durchläuft und wie andere Planeten scheinbar den Tierkreis durchlaufen, so ist es der menschlichen Seele möglich, einen Geisteskreis zu durchlaufen, welcher zwölf Weltanschauungsbilder enthält. Ja, man kann sogar die Eigentümlichkeiten dieser Weltanschauungsbilder in Zusammenhang bringen mit den einzelnen Zeichen des Tierkreises. Und zwar ist dieses In-Beziehung-Bringen gar nichts Willkürliches, sondern es besteht wirklich ein ähnliches Verhältnis zwischen den einzelnen Tierkreisbildern und der Erde wie zwischen diesen zwölf Weltanschauungen und der menschlichen Seele. Das ist folgendermaßen gemeint.

Zunächst können wir ja nicht davon sprechen, daß ein leichtverständliches Verhältnis bestünde zum Beispiel zwischen dem Tierkreisbilde Widder und der Erde. Aber wenn die Sonne, der Saturn oder der Merkur so stehen, daß man sie von der Erde aus im Zeichen des Widders sieht, so wirken sie anders, als wenn sie so stehen, daß man sie im Zeichen des Löwen sieht. Es ist also die Wirkung, die aus dem Kosmos zum Beispiel von den einzelnen Planeten zu uns kommt, verschieden, je nachdem die einzelnen Planeten das eine oder das andere Tierkreisbild bedecken. Bei der menschlichen Seele ist es uns sogar leichter, den Einfluß dieser zwölf «Geistes-Tierkreisbilder» anzuerkennen. Es gibt Seelen, die gewissermaßen ganz dahin tendieren, allein Einfluß auf die Konfiguration ihres Innenlebens, auf ihre wissenschaftliche, philosophische oder sonstige Geistesrichtung dahin zu bekommen, daß sie sich gleichsam vom Idealismus bescheinen lassen in der Seele. Andere lassen sich in der Seele von dem Materialismus bescheinen, andere vom Sensualismus. Man ist nicht Sensualist, Materialist, Spiritualist oder Pneumatiker, weil die eine oder die andere Anschauung richtig ist und man die Richtigkeit der einen oder der anderen Anschauung einsehen kann, sondern man ist Pneumatiker, Spiritualist, Materialist oder Sensualist, weil man in seiner Seele so veranlagt ist, daß man von dem betreffenden GeistesTierkteisbilde geistig-seelisch beschienen wird. So haben wir in diesen zwölf Geistes-Tierkreisbildern etwas, was uns tief hineinführen kann in die Art, wie menschliche Weltanschauungen entstehen, und was uns tief hineinführen kann in die Gründe, warum die Menschen auf der einen Seite sich streiten über Weltanschauungen, auf der anderen Seite aber sich nicht streiten sollten, sondern viel lieber einsehen sollten, wodurch es kommt, daß die Menschen verschiedene Weltanschauungsnuancen haben. Wenn es für gewisse Epochen dennoch notwendig ist, die eine oder die andere Weltanschauungsrichtung streng zurückzuweisen, so werden wir den Grund von diesem im morgigen Vortrage noch anzugeben haben. Was ich bis jetzt gesagt habe, bezieht sich also auf die Ausformung des menschlichen Gedankens durch den geistigen Kosmos der gleichsam in unserem geistigen Umktreise ruhenden zwölf Geistes-Tierkreisbilder.

Aber es gibt noch etwas anderes, was die menschlichen Weltanschauungen bestimmt. Dies andere werden Sie am besten dadurch einsehen, daß ich Ihnen zunächst das Folgende zeige.

Man kann in seiner Seele so gestimmt sein, gleichgültig jetzt sogar, von welchem dieser zwölf Geistes-Tierkreisbilder man in der Seele beschienen ist, daß man diese Stimmung der Seele, die sich in der ganzen Konfiguration der Weltanschauung dieser Seele zum Ausdruck bringt, bezeichnen kann als Gnosis. Man kann ein Gnostiker sein. Man ist ein Gnostiker, wenn man daraufhin gestimmt ist, durch gewisse in der Seele selbst liegende Erkenntniskräfte, nicht durch die Sinne oder dergleichen, die Dinge der Welt kennenzulernen. Man kann ein Gnostiker sein und zum Beispiel eine gewisse Neigung haben, sich bescheinen zu lassen von dem Geistes-Tierkreisbilde, das wir hier als Spiritualismus bezeichnet haben. Dann wird man in seiner Gnostik tief hineinleuchten können in die Zusammenhänge der geistigen Welten.

Man kann aber auch zum Beispiel ein Gnostiker des Idealismus sein; dann wird man eine besondere Veranlagung haben, die Ideale der Menschheit und die Ideen der Welt klar zu sehen. Der Unterschied ist ja vorhanden zwischen dem einen und dem anderen Menschen auch in bezug auf den Idealismus, den die beiden Menschen haben können. So ist der eine ein idealistischer Schwärmer, der immer davon redet, daß er Idealist ist, der nur immer das Wort Ideal, Ideal, Ideal im Munde führt, aber nicht viele Ideale kennt, der nicht die Fähigkeit hat, in scharfen Konturen und mit innerlichem Schauen wirklich die Ideale vor seine Seele zu rufen. Ein solcher unterscheidet sich dann von dem anderen, der nicht nur von Idealen redet, sondern die Ideale in seiner Seele so zu zeichnen weiß wie ein scharf hingemaltes Bild. Der letztere, der den Idealismus ganz konkret innerlich ergreift, so intensiv ergreift, wie man mit der Hand äußere Dinge ergreift, der ist auf dem Gebiete des Idealismus ein Gnostiker. Man könnte auch so sagen: Er ist überhaupt ein Gnostiker, aber er läßt sich insbesondere von dem Geistes-Tierkreisbilde des Idealismus bescheinen.

Es gibt Menschen, welche sich besonders stark bescheinen lassen von dem Weltanschauungsbilde des Realismus, die aber so durch die Welt gehen, daß sie durch die ganze Art, wie sie die Welt empfinden, wie sie der Welt gegenübertreten, den andern Menschen viel, viel sagen können von dieser Welt. Sie sind weder Idealisten noch Spiritualisten; sie sind ganz gewöhnliche Realisten. Sie sind imstande, wirklich fein zu empfinden, was in der äußeren Realität um sie herum ist, sie sind fein empfänglich für die Eigentümlichkeiten der Dinge. Sie sind Gnostiker, richtige Gnostiker; nur sind sie Gnostiker des Realismus. Solche Gnostiker des Realismus gibt es, und manchmal sind Spiritualisten oder Idealisten gar nicht Gnostiker des Realismus. Wir können sogar finden, daß Leute, die sich gute Theosophen nennen, durch eine Bildergalerie durchgehen und gar nichts zu sagen haben über die Bilder, während andere, die gar nicht Theosophen sind, die aber Gnostiker des Realismus sind, unendlich Bedeutungsvolles dadurch zu sagen wissen, daß sie mit ihrer ganzen Persönlichkeit in Berührung sind mit der ganzen Realität der Dinge. Oder wie viele Theosophen gehen hinaus in die Natur und wissen gar nicht das ganz Erhabene und Große der Natur mit der ganzen Seele aufzufassen: sie sind nicht Gnostiker des Realismus. Es gibt Gnostiker des Realismus. Es gibt auch Gnostiker des Materialismus. Das sind allerdings sonderbare Gnostiker. Aber ganz in dem Sinne, wie man Gnostiker des Realismus ist, kann man Gnostiker des Materialismus sein; aber es sind das Menschen, die nur Sinn und Gefühl und Empfinden haben für alles Stoffliche, die das Stoffliche durch die unmittelbare Berührung kennenzulernen suchen, wie der Hund, der die Stoffe beriecht und dadurch intim kennenlernt und der eigentlich in bezug auf die materiellen Dinge ein ausgezeichneter Gnostiker ist.

Man kann Gnostiker sein für alle zwölf Weltanschauungsbilder. Das heißt, wenn wir die Gnosis richtig hineinstellen wollen, müssen wir es so machen, daß wir einen Kreis zeichnen und daß uns der ganze Kreis bedeutet: Die Gnosis kann herumwandeln durch alle zwölf Weltanschauungsbilder. Wie ein Planet die zwölf Tierkreisbilder durchwandelt, so kann die Gnosis alle zwölf Weltanschauungsbilder durchwandeln.

Allerdings wird die Gnosis die größten Dienste für das Heil der Seelen dann leisten, wenn die gnostische Stimmung angewendet wird für den Spiritualismus. Man könnte sagen: Die Gnosis ist im Spiritualismus so recht zu Hause. Sie ist da in «ihrem» Hause. Sie ist außer ihrem Hause in den anderen Weltanschauungsbildern. Logisch hat man nicht die Berechtigung zu sagen, es könnte keine materialistische Gnostik geben. Die Pedanten der Begriffe und Ideen werden mit solchen Dingen leichter fertig als die gesunden Logiker, die es etwas komplizierter haben. Man könnte zum Beispiel sagen: Ich will nichts anderes Gnosis nennen, als was in den Geist eindringt. Das ist eine willkürliche Begriffsbestimmung, ist ebenso willkürlich, wie wenn jemand sagen würde: Veilchen habe ich bis jetzt nur in Österreich gesehen, also nenne ich Veilchen nur das, was in Österreich wächst und die Veilchenfarbe hat, anderes nicht. Logisch ist es ebenso unmöglich zu sagen, Gnosis gebe es nur im Weltanschauungsbilde des Spiritualismus; denn Gnosis ist ein «Planet», der die Geistes-Sternbilder durchläuft.

Es gibt eine andere Weltanschauungsstimmung. «Stimmung» sage ich hierbei, während ich sonst von «Nuancen» und «Bildern» spreche. Und man hat in den neueren Zeiten gemeint, in einer leichteren Art - doch ist auch hier «das Leichte schwer»! — diese zweite Weltanschauungsstimmung kennenzulernen, weil diese im Geistes-Sternbilde des Idealismus gerade von Hegel vertreten worden ist. Aber diejenige Art, die Welt zu betrachten, diese besondere Weltanschauungsstimmung, die Hegel gehabt hat, braucht nicht, wie bei ihm, bloß im Geistes-Sternbilde des Idealismus zu stehen, sondern sie kann wieder durch alle Sternbilder durchgehen. Es ist die Weltanschauungsstimmung des Logismus. Diese Weltanschauungsstimmung des Logismus besteht vorzugsweise darin, daß sich die Seele in die Lage versetzen kann, wirkliche Gedanken, Begriffe und Ideen in sich gegenwärtig sein zu lassen, diese Gedanken und Ideen so in sich gegenwärtig zu haben, daß eine solche Seele von einem Begriffe oder einem Gedanken zu dem anderen so kommt, wie man, wenn man einen menschlichen Organismus ansieht, von dem Auge zur Nase und zum Mund kommt und alles dieses als zusammengehörig betrachtet, wie es bei Hegel ist, wo alle Begriffe, die er fassen kann, sich zu einem großen Begriffsorganismus zusammenordnen. Das ist ein logischer Begriffsorganismus. Hegel war einfach imstande, alles, was in der Welt als Gedanke gefunden werden kann, aufzusuchen und aufzunehmen, Gedanken an Gedanken zu reihen und daraus einen Organismus zu machen: Logismus! Man kann den Logismus ausbilden so wie Hegel, im Sternbilde des Idealismus, kann ihn ausbilden so wie Fichte, im Sternbilde des Psychismus, und man kann ihn in anderen Geistes-Sternbildern ausbilden. Wiederum ist der Logismus etwas, was wie ein Planet durch die Tierkreisbilder durchgeht, was kreisförmig durch die zwölf Geistes-Tierkreisbilder geht.

Eine dritte Stimmung der Seele, die Weltanschauungen macht, können wir zum Beispiel bei Schopenhauer studieren. Während Hegels Seele, wenn er hinschaut auf die Welt, so gestimmt ist, daß zunächst in dieser Hegel-Seele alles, was in der Welt Begriff ist, als der Logismus sich ergibt, faßt Schopenhauer durch die besondere Stimmung seiner Seele alles das in der Seele auf, was willensartig ist. Für ihn sind die Naturkräfte Wille, die Härte des Steines ist Wille, alles, was Realität ist, ist Wille. Das kommt aus der besonderen Stimmung seiner Seele. Nun kann man eine solche Weltanschauung des Willens, solche Weltanschauungsstimmung des Willens wiederum wie einen Planeten betrachten, der durch alle zwölf Geistes-Tierkreisbilder geht. Ich will diese Weltanschauungsstimmung Voluntarismus nennen. Es ist die dritte Weltanschauungsstimmung. Schopenhauer war Voluntarist, und er war in seiner Seele vorzugsweise so konstituiert, daß er sich aussetzte dem Geistes-Sternbilde des Psychismus. So entstand die eigentümliche Schopenhauersche Willensmetaphysik: Voluntarismus im Geistes-Sternbilde des Psychismus.

Nehmen Sie einmal an, es würde jemand Voluntarist sein und besonders hinneigen zu dem Geistes-Sternbilde des Monadismus. Dann würde er nicht wie Schopenhauer so eine Einheitsseele, die eigentlich Wille ist, der Welt zugrunde legen, sondern er würde viele Monaden, die aber Willenswesen sind, der Welt zugrunde legen. Diese Welt des monadologischen Voluntarismus hat in schönster, scharfsinnigster und, ich möchte sagen, innigster Weise der österreichische Dichterphilosoph Hazmerling ausgebildet. Wodurch ist die eigentümliche Lehre, die Sie in der «Atomistik des Willens» von Hamerling haben, zustande gekommen? Dadurch, daß seine Seele voluntaristisch gestimmt war und er sich vorzugsweise ausgesetzt hat dem Geistes-Sternbilde des Monadismus. Wenn wit Zeit hätten, könnten wir für jede Seelenstimmung in jedem Sternbilde Beispiele anführen. Sie finden sich in der Welt.

Eine besondere Seelenstimmung ist diese, welche nun gar nicht geneigt ist, viel nachzudenken oder nachzusinnen, ob nun hinter den Erscheinungen dieses oder jenes noch ist, wie es zum Beispiel die gnostische Stimmung tut oder wie es die logische oder die voluntatistische Stimmung tut, sondern die einfach sagt: Ich will das, was mir in der Welt entgegentritt, was sich mir zeigt, was sich mir äußerlich offenbart, meiner Weltanschauung eingliedern. Das kann man wieder auf allen Gebieten, das heißt durch alle Geistes-Sternbilder durch. Man kann es als Materialist machen, daß man nur das nimmt, was einem äußerlich entgegentritt; man kann es auch als Spiritualist machen. Man bemüht sich nicht, einen besonderen Zusammenhang hinter den Erscheinungen zu suchen, sondern man läßt die Dinge an sich herankommen und wartet, was sich einem darbietet. Solche Seelenstimmung kann man Empirismus nennen. Empirismus heißt eine Seelenstimmung, welche die Erfahrung, wie sie sich darbietet, einfach hinnimmt. Durch alle zwölf Geistes-Sternbilder hindurch kann man Empirist sein, Erfahrungsweltanschauungs-Mensch. Empirismus ist die vierte Seelenstimmung, die durch alle zwölf GeistesSternbilder durchgehen kann.

Ebenso kann man für die Weltanschauung eine solche Seelenstimmung entwickeln, welche sich nicht zufrieden gibt mit demjenigen, was die Erfahrung, die einem so entgegentritt, was das Erleben, dem man ausgesetzt ist, ergibt, wie das beim Empirismus der Fall ist; sondern man kann sich sagen, das heißt, man kann als eine innere Notwendigkeit durchfühlen die Seelenstimmung: Der Mensch ist in die Welt hereingestellt; in seiner eigenen Seele erlebt er etwas über die Welt, was er äußerlich nicht erleben kann. Da erst enthüllt die Welt ihre Geheimnisse. Man mag um sich herumschauen - man sieht nicht das, was die Welt an Geheimnissen enthält. - Solche Seelenstimmung kann oftmals sagen: Was hilft mir die Gnosis, die sich mit aller Mühe emporringt zu allerlei Schauungen? Die Dinge der äußeren Welt, über die man Schauungen hat, können einem doch nicht das Innere der Welt offenbaren. Was hilft mir der Logismus zu einer Weltanschauung? In dem Logismus drückt sich das Wesen der Welt nicht aus. Was hilft Spekulation über den Willen? Das bringt nur davon ab, in die Tiefen der eigenen Seele zu schauen. Und in diese Tiefen blickt man nicht, wenn die Seele will, sondern gerade dann, wenn sie hingebend, willenlos ist. — Also auch der Voluntarismus ist nicht die Seelenstimmung, die die Seele hier braucht, auch nicht der Empirismus, das bloße Hinschauen oder Hinhorchen auf das, was die Erfahrung, das Erleben gibt; sondern das innerliche Suchen, wenn die Seele ruhig geworden ist, wie der Gott in der Seele aufleuchtet. Sie merken, diese Seelenstimmung kann genannt werden die Mystik.

Mystiker kann man wieder durch alle zwölf Geistes-Sternbilder hindurch sein. Es wird gewiß nicht sonderlich günstig sein, wenn man Mystiker des Materialismus ist, das heißt, wenn man nicht das Geistige, das Spirituelle, sondern das Materielle innerlich erlebt. Denn Mystiker des Materialismus ist eigentlich der, welcher sich ein besonders feines Empfinden zum Beispiel für die Art des Befindens angeeignet hat, in das man kommt, wenn man den einen oder den anderen Stoff genießt. Es ist etwas anderes, wenn man, ich will sagen, den Saft der einen Pflanze genießt oder den einer anderen Pflanze und nun wartet, was dadurch im Organismus bewirkt wird. Man wächst also in seinem Erleben mit der Materie zusammen, wird Mystiker der Materie. Es kann sogar sein, daß das eine Aufgabe für das Leben werden kann, eine Aufgabe so für das Leben, daß man verfolgt, auf welche Art der eine oder der andere Stoff, der von dieser oder jener Pflanze kommt, besonders auf den Organismus wirkt; denn der eine wirkt besonders auf dieses, der andere besonders auf jenes Organ. Und so Mystiker des Materialismus sein ist eine Vorbedingung für die Untersuchung der einzelnen Stoffe hinsichtlich ihrer Heilkraft. Man merkt, was die Stoffe tun im Organismus. — Man kann Mystiker der Stoffwelt sein, man kann Mystiker des Idealismus sein. Ein gewöhnlicher Idealist oder ein gnostischer Idealist ist nicht Mystiker des Idealismus. Mystiker des Idealismus ist der, welcher vor allen Dingen in der eigenen Seele die Möglichkeit hat, aus im Innern verborgenen Quellen heraufzuholen die Ideale der Menschheit, sie als inneres Göttliches zu empfinden und als solches sich vor die Seele zu stellen. Ein Mystiker des Idealismus ist zum Beispiel der Mezster Eckhart.

Nun kann die Seele so gestimmt sein, daß sie nicht das gewahr werden kann, was in ihrem Innern aufsteigt und was sich wie die eigentliche innere Lösung der Weltenrätsel ausnimmt, sondern eine Seele kann so gestimmt sein, daß sie sich sagt: Ja, in der Welt ist irgend etwas hinter allen Dingen, wie hinter meiner eigenen Wesenheit, soweit ich diese Wesenheit wahrnehme. Aber ich kann kein Mystiker sein. Der Mystiker glaubt, das fließt herein in seine Seele. Ich fühle es nicht in meine Seele hereinfließen; ich fühle nur, daß es da sein muß, draußen. — Man setzt in dieser Seelenstimmung voraus, daß außer unserer Seele und außer dem, was unsere Seele erfahren kann, das Wesen der Dinge steckt; aber man setzt nicht voraus, daß dieses Wesen der Dinge in die Seele selber hereinkommen kann, wie der Mystiker es voraussetzt. Wenn man voraussetzt, daß hinter allem noch etwas ist, das man nicht erreichen kann in der Wahrnehmung, dann ist man - das ist vielleicht das beste Wort dafür — Transzendentalist. Man nimmt an, daß das Wesen der Dinge transzendent ist, daß es nicht in die Seele hereinkommt, wie es der Mystiker annimmt. Also: Transzendentalismus. Die Stimmung des Transzendentalisten ist so, daß er das Gefühl hat: Wenn ich die Dinge wahrnehme, so kommt das Wesen der Dinge an mich heran; nur die Wahrnehmung selber ist nicht dieses Wesen. Das Wesen steckt dahinter, aber es kommt an den Menschen heran.

Es kann nun der Mensch mit seinen Wahrnehmungen, mit alledem, was seine Erkenntniskräfte sind, gleichsam noch mehr das Wesen der Dinge abschieben, als es der Transzendentalist tut. Man kann sagen: Für die menschliche äußere Erkenntniskraft ist das Wesen der Dinge überhaupt nicht erreichbar. Der Transzendentalist sagt: Wenn du mit deinem Auge Rot und Blau siehst, so ist das, was du als Rot und Blau siehst, nicht das Wesen der Dinge; aber dahinter steckt es. Du mußt deine Augen anwenden, dann dringst du bis an das Wesen der Dinge heran. Dahinter ist es. - Diese Seelenstimmung aber, die ich jetzt meine, will nicht im Transzendentalismus leben, sondern sie sagt: Man mag noch so sehr Rot oder Blau oder diesen oder jenen Ton erleben, das alles drückt nicht das Wesen der Dinge aus. Das ist erst dahinter verborgen. Da, wo ich wahrnehme, stößt gar nicht das Wesen der Dinge an. - Wer so spricht, der spricht ähnlich der Art, wie wir gewöhnlich sprechen, die wir durchaus auf dem Standpunkte stehen: In dem äußeren Sinnenschein, in der Maja, drückt sich nicht das Wesen der Dinge aus. Wir wären Transzendentalisten, wenn wir sagten: Um uns herum breitet sich die Welt aus, und diese Welt kündet überall an das Wesen. Das sind wir nicht, wenn wir sagen: Diese Welt ist Maja, und man muß auf eine andere Weise als durch das äußere Wahrnehmen der Sinne und die gewöhnlichen Erkenntnismittel das Innere der Dinge suchen, Okkultismus ist das, die Seelenstimmung des Okkultismus.

Man kann wiederum durch alle Geistes-Tierkreiszeichen hindurch Okkultist sein. Man kann durchaus Okkultist auch sogar des Materialismus sein. Ja, die vernünftigen Naturforscher der Gegenwart sind alle Okkultisten des Materialismus, denn sie reden von Atomen. Wenn sie aber nicht unvernünftig sind, wird es ihnen gar nicht einfallen, zu behaupten, daß man mit irgendeiner Methode an das Atom herankommen kann. Das Atom bleibt im Okkulten. Sie lieben es nur nicht, Okkultisten genannt zu werden, aber sie sind es im vollsten Sinne des Wortes.

Andere Weltanschauungsstimmungen als diese sieben, die ich hier aufgezeichnet habe, kann es im wesentlichen nicht geben, nur Übergänge von einer zur andern. So müssen wir also unterscheiden nicht nur zwölf verschiedene Weltanschauungsnuancen, die uns wie ruhend entgegentreten, sondern in jeder dieser Weltanschauungsnuancen ist eine ganz besondere Stimmung der Menschenseele möglich. Daraus ersehen Sie, wie ungeheuer mannigfaltig die Weltanschauungen der menschlichen Persönlichkeiten sein können. Man kann jede dieser sieben Weltanschauungsstimmungen besonders ausbilden, aber jede dieser Weltanschauungsstimmungen wieder einseitig in der einen oder anderen Nuance. Was ich hier aufgezeichnet habe, das ist tatsächlich auf dem Gebiete des Geistigen das Korrelat desjenigen, was äußerlich in der Welt das Verhältnis zwischen den Tierkreisbildern und den Planeten ist, wie wir es eben in der Geisteswissenschaft als die sieben bekannten Planeten oftmals angeführt haben, und man hat so ein Bild, gleichsam ein äußeres Bild, das wir nicht geschaffen haben, sondern das im Kosmos drinnensteht, für die Beziehungen unserer sieben Weltanschauungsstimmungen zu unseren zwölf Weltanschauungsnuancen. Und richtig witd man dieses Bild empfinden, wenn man es in der folgenden Weise empfindet.

Man beginne beim Idealismus, bezeichne diesen als das GeistesTierkreisbild des Widder, bezeichne in gleicher Weise den Rationalismus als Stier, den Mathematizismus als Zwillinge, den Materialismus als Krebs, den Sensualismus als Löwe, den Phänomenalismus als Jungfrau, den Realismus als Waage, den Dynamismus als Skorpion, den Monadismus als Schütze, den Spiritualismus als Steinbock, den Pneumatismus als Wassermann, den Psychismus als Fische. Die Beziehungen, die zwischen den einzelnen Tierkreisbildern in bezug auf das äußere Räumlich-Materielle bestehen, sind tatsächlich auf dem Gebiete des Geistes zwischen diesen Weltanschauungen vorhanden. Und was die einzelnen von uns bezeichneten Planeten bei ihrem Kreisen längs des Tierkreises für Verhältnisse eingehen, das entspricht den Verhältnissen, welche die sieben Weltanschauungsstimmungen eingehen, aber so, daß wir empfinden können die Gnosis als Saturn, den Logismus als Jupiter, den Voluntarismus als Mars, den Empirismus als Sonne, die Mystik als Venus, den Transzendentalismus als Merkur und den Okkultismus als Mond.

Bis auf die äußeren Bilder - aber das ist nicht die Hauptsache; die Hauptsache ist tatsächlich, daß die tiefinnersten Beziehungen dieser Parallelisierung entsprechen -, aber selbst bis auf die äußeren Bilder werden Sie, wo etwas so zu konstatieren ist, etwas Ähnliches finden. Der Mond bleibt okkult, unsichtbar, wenn er Neumond ist; er muß erst das Licht von der Sonne herangeführt bekommen, geradeso wie die okkulten Dinge okkult bleiben, bis sich das Seelenvermögen dutch die Meditation, Konzentration und so weiter erhebt und die okkulten Dinge beleuchtet. Der Mensch, der durch die Welt geht und sich nur auf die Sonne verläßt, der nur aufnimmt, was die Sonne bescheint, ist Empitist. Wer auch noch etwas nachdenkt über das, was die Sonne bescheint, und auch noch die Gedanken behält, wenn die Sonne untergegangen ist, der ist nicht mehr Empirist, weil er sich nicht mehr auf die Sonne verläßt. «Sonne» ist das Symbolum des Empirismus. — Für alle diese Dinge könnte ich das weiter ausführen, aber wir haben ja nur vier Stunden zu diesem wichtigen Thema, und es wird Ihnen vorläufig überlassen bleiben müssen, genauere Beziehungen durch Ihre Gedanken oder Ihr sonstiges Forschen zu erkunden. Sie sind nicht einmal schwierig zu finden, wenn man einmal das Schema angegeben hat.

Nun kommt es wohl in der Welt allzuoft vor, daß die Menschen wenig nach Allseitigkeit streben. Man müßte ja wirklich, wenn man es mit der Wahrheit ernst nimmt, sich die zwölf Weltanschauungsnuancen in der Seele repräsentieren können, und man müßte in sich etwas von diesem erlebt haben: Wie erlebt es sich als Gnostiker? Wie erlebt es sich als Logiker, wie als Voluntarist, wie als Empirist, wie als Mystiker, wie als Transzendentalist? Und wie erlebt es sich als Okkultist? Probeweise muß ja das im Grunde genommen jeder durchmachen, der wirklich in die Geheimnisse der Welt im Sinne der geistigen Forschung eindringen will. Und wenn auch nicht das, was in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» steht, gerade auf diese Ausführungen hin zugeschnitten ist, so ist doch alles darin, nur von anderen Gesichtspunkten aus, geschildert, was uns in die einzelnen Stimmungen führen kann, die hier mit der gnostischen Stimmung, mit der Jupiterstimmung und so weiter bezeichnet sind.

Es kommt in der Welt oft vor, daß der Mensch so einseitig ist, daß er sich nur einem Sternbilde aussetzt oder nur einer Stimmung. Gerade große Menschen auf dem Gebiete der Weltanschauungen haben diese Einseitigkeit allzu oft. So ist zum Beispiel Hamerling ausgesptochen ein voluntaristischer Monadist oder ein monadologischer Voluntarist, Schopenhauer ein ausgesprochener voluntaristischer Psychiker. Gerade die großen Menschen haben sozusagen ihre Seele so eingestellt, daß ihre planetarische Weltanschauungsstimmung in einem ganz bestimmten geistigen Sternbilde steht. Die anderen Menschen finden sich viel leichter ab mit den verschiedenen Standpunkten, wie man es so nennt. Aber es kann auch vorkommen, daß Menschen von verschiedenen Seiten her gleichsam angeregt werden für ihre Weltanschauung, für das, was sie als Weltanschauung aufstellen. So zum Beispiel kann es vorkommen, daß jemand ein guter Logist ist, aber seine logistische Stimmung steht im Geistes-Sternbilde des Sensualismus. Er kann zugleich ein guter Empiriker sein, aber seine empiristische Stimmung steht im Sternbilde des Mathematizismus. Das kann vorkommen. Wenn dieses so ist, dann stellt man ein ganz bestimmtes Weltanschauungsbild auf. Wir haben gerade in der Gegenwart dieses Weltanschauungsbild, das dadurch zustande gekommen ist, daß jemand seine Sonne - jetzt geistig gesprochen - in den Zwillingen und seinen Jupiter im Löwen hat; das ist Wundt. Und man wird alles einzelne begreifen, was in der philosophischen Literatur bei Wundt auftritt, wenn man hinter das Geheimnis seiner besonderen Seelenkonfiguration gekommen ist.

Besonders günstig liegt es, wenn ein Mensch die verschiedenen Seelenstimmungen — Okkultismus, Transzendentalismus, Mystik, Empirismus, Voluntarismus, Logismus, Gnosis — wirklich so übungsweise erlebt hat, daß er sie sich vergegenwärtigen kann, sie gleichsam in ihrer Wirkung auf einmal empfinden kann und dann alle diese Stimmungen - wie auf einmal - in das eine Sternbild des Phänomenalismus stellt, in die Jungfrau. Da tritt wirklich für seine Erscheinungen wie in Phänomenen vor ihm mit einer ganz besonderen Grandiosität das auf, was ihm in einer günstigen Weise die Welt enthüllen kann. Wenn man in derselben Weise hintereinander die einzelnen Weltanschauungsstimmungen stellt in bezug auf ein anderes Sternbild, so ist das nicht so gut zunächst. Daher hat man in vielen alten Mysterienschulen gerade diese Stimmung, die ich jetzt dadurch bezeichnet habe, daß gleichsam alle Seelenplaneten in dem GeistesSternbilde der Jungfrau stehen, für die Schüler herbeigeführt, weil diese dadurch am leichtesten eingedrungen sind in die Welt. Sie haben die Phänomene aufgefaßt, aber gnostisch, logisch und so weiter aufgefaßt; sie waren in der Lage, hinter die Phänomene zu kommen. Sie haben die Welt nicht grobklotzig empfunden. Das würde nur dann sein, wenn die Seelenstimmung des Voluntarismus auf den Skorpion eingestellt ist. Kurz, durch die Konstellation, die gegeben ist durch die Seelen-Weltanschauungsstimmungen, die das planetarische Element sind, und durch die Weltanschauungsnuancen, die das Element des Geistes-Tierkreises sind, wird das hervorgerufen, was der Mensch als seine Weltanschauung durch die Welt trägt in irgendeiner Inkarnation.

Es kommt allerdings noch eines dazu. Das ist, daß diese Weltanschauungen - es sind ihrer schon sehr viele Nuancen, wenn Sie sich alle Kombinationen suchen - noch dadurch modifiziert werden, daß sie alle einen ganz bestimmten Ton erhalten können. Aber auf diesem Gebiete des Tones haben wir nur dreierlei zu unterscheiden. Alle Weltanschauungen, alle Kombinationen, die auf diese Weise entstehen, können wieder in dreifacher Weise auftreten. Sie können erstens sein theistisch, so daß ich das, was in der Seele als Ton auftritt, zu benennen habe mit Theismus. Sie können so sein, daß wir im Gegensatz zum Theismus den betreffenden Seelenton zu nennen haben Intuitismus. Theismus entsteht, wenn der Mensch sich an alles Äußere hält, um seinen Gott zu finden, wenn er seinen Gott im Äußeren sucht. Der althebräische Monotheismus war vorzugsweise eine theistische Weltanschauung. Intuitismus entsteht, wenn der Mensch seine Weltanschauung vorzugsweise durch das sucht, was intuitiv in seinem Inneren aufleuchtet. Es gibt zu diesen beiden noch einen dritten Ton; das ist der Naturalismus.

Diese drei Seelentöne haben auch ein Abbild in der äußeren Welt des Kosmos, und zwar verhalten sie sich nun in der menschlichen Seele genauso wie Sonne, Mond und Erde, so daß der Theismus der Sonne entspricht - jetzt Sonne als Fixstern, nicht als Planet aufgefaßt -, daß der Intuitismus dem Mond entspricht und der Naturalismus der Erde. Derjenige - übersetzen Sie sich das einzelne, was hier als Sonne, Mond und Erde bezeichnet ist, ins Geistige —, welcher über die Erscheinungen der Welt hinausgeht und sagt: Wenn ich hinausschaue, so offenbart sich mir in alledem der Gott, der die Welt erfüllt, - der Erdenmensch, der sich aufrichtet, wenn er in die Sonnenstrahlen kommt, ist der Theist. Der Mensch, der nicht über die Naturvorgänge hinausgeht, sondern bei den einzelnen Erschetnungen stehenbleibt, so wie der, welcher nie seinen Blick zur Sonne hinaufrichtet, sondern nur auf das sieht, was ihm die Sonne hervorbringt auf der Erde, der ist Naturalist. Der, welcher das Beste, was er in der Seele haben kann, aufsucht dadurch, daß er es in seinen Intuitionen aufgehen läßt, der ist wie der den Mond besingende und vom silbernen, milden Mondenglanz in seiner Seele angeregte intuitistische Dichter und läßt sich mit ihm vergleichen. Wie man mit der Phantasie das Mondenlicht in Zusammenhang bringen kann, so muß man okkult den Intuitisten, wie er hier gemeint ist, mit dem Monde in Beziehung bringen.

Endlich gibt es noch ein Viertes; das ist allerdings nur in einem einzigen Element vorhanden. Wenn der Mensch sich gewissermaßen in bezug auf alle Weltanschauung ganz nur an das hält, was er an oder um oder in sich selbst erfahren kann:.das ist Anthropomorphismus.

Er entspricht der Erde, wenn man diese als solche betrachtet, abgesehen davon, ob sie von der Sonne, vom Mond oder anderem umgeben ist. Wie wir die Erde für sich allein betrachten können, so können wir auch in bezug auf Weltanschauungen auf nichts Rücksicht nehmen als auf das, was wir als Menschen in uns finden können. Dann wird der in der Welt so verbreitete Anthropomorphismus entstehen.

Geht man hinaus über das, was der Mensch ist, so wie man zur Erklärung der Erscheinung der Erde hinausgehen muß zu Sonne und Mond - was die gegenwärtige Wissenschaft nicht tut -, so kommt man dazu, dreierlei als nebeneinander berechtigt anerkennen zu müssen: Theismus, Intuitismus und Naturalismus. Denn nicht, daß man auf einem dieser Töne besteht, sondern daß man sie zusammenklingen läßt, entspricht dem, was die Wahrheit ist. Und wie unsere engere Körperlichkeit mit Sonne, Mond und Erde wieder hineingestellt ist in die sieben Planeten, so ist hineingestellt Anthropomorphismus als die trivialste Weltanschauung in das, was zusammenklingen kann aus Theismus, Intuitismus und Naturalismus, und dieses zusammen wieder in das, was zusammenklingen kann aus den sieben Seelenstimmungen. Und diese sieben Seelenstimmungen nuancieren sich nach den zwölf Zeichen des Tierkreises.

Sie sehen schon, dem Namen nach, und zwar nur dem Namen nach, ist nicht eine Weltanschauung wahr, sondern es sind \(12 + 7 = 19 + 3 = 22 + 1 = 23\) Weltanschauungen berechtigt. Dreiundzwanzig berechtigte Namen für Weltanschauungen haben wir. Aber alles andere kann noch dadurch entstehen, daß die entsprechenden Planeten in den zwölf Geistes-Tierkreisbildern herumlaufen.

Und nun versuchen Sie, aus dem, was jetzt auseinandergesetzt worden ist, sich ein Empfinden anzueignen für die Aufgabe, welche die Geisteswissenschaft für das Friedenstiften innerhalb der verschiedenen Weltanschauungen hat, für das Friedenstiften aus der Erkenntnis heraus, daß die Weltanschauungen miteinander, in ihrem gegenseitigen Aufeinanderwirken, in gewisser Beziehung erklärlich sind, daß sie aber alle nicht ins Innere der Wahrheit führen können, wenn sie einseitig bleiben, sondern daß man gleichsam den Wahrheitswert der verschiedenen Weltanschauungen innerlich in sich erfahren muß, um wirklich - wir dürfen so sagen - mit der Wahrheit zutechtzukommen. So wie Sie sich denken können den physischen Kosmos: den Tierkreis, das Planetensystem, Sonne, Mond und Erde zusammen, die Erde für sich, so können Sie sich ein geistiges Weltenall denken: Anthropomorphismus; Theismus, Intuitismus, Naturalismus; Gnosis, Logismus, Voluntarismus, Empitismus, Mystik, Transzendentalismus, Okkultismus; und das alles verlaufend in den zwölf Geistes-Tierkreisbildern. Das ist vorhanden; nur ist es geistig vorhanden. So wahr als der physische Kosmos physisch vorhanden ist, so wahr ist das geistig vorhanden.

In diejenige Hirnhälfte, die der Anatom findet, von der man ja sagen kann, daß sie die halbkugelförmige ist, in sie wirken herein vorzugsweise diejenigen Wirkungen des Geisteskosmos, die von den oberen Nuancen ausgehen. Dagegen gibt es einen unsichtbaren Teil des Gehirns, der nur, wenn man den Ätherleib betrachtet, sichtbar ist; der ist vorzugsweise von dem unteren Teil des Geisteskosmos beeinflußt (siehe Zeichnung.) Aber wie ist diese Beeinflussung? Sagen wir, bei jemandem ist es so, daß er mit seinem Logismus eingestellt ist in den Sensualismus, daß er eingestellt ist mit seinem Empirismus in den Mathematizismus. Dann gibt das, was auf diese Weise zustande kommt, Kräfte, die in sein Gehirn hereinwirken, und jener obere Teil seines Gehirns ist dann besonders regsam und übertönt die anderen. Unzählige Nuancen von Gehirntätigkeiten kommen dadurch zustande, daß das Gehirn gleichsam im geistigen Kosmos schwimmt und die Kräfte auf diese Weise ins Gehirn hereinwirken, wie wir das jetzt haben darstellen können. So mannigfaltig sind wirklich die menschlichen Gehirne, als sie mannigfaltig sein können nach den Kombinationen, die sich aus diesem geistigen Kosmos ergeben. Was in jenem unteren Teile des geistigen Kosmos ist, das wirkt gar nicht einmal auf das physische Gehirn, sondern auf das Äthergehirn.

14

Wenn man von alledem spricht, dann ist wohl der beste Eindruck, den man davon erhalten kann, der, daß man sagt: Es eröffnet einem das die Empfindung für das Unendliche der Welt, für das qualitativ Großartige der Welt, für die Möglichkeit, daß man als Mensch in unendlicher Mannigfaltigkeit in dieser Welt existieren kann. Wahrhaftig, wenn wir nur dieses betrachten können, dann können wir uns schon sagen: Es fehlt wahrlich nicht an Möglichkeiten, daß wir verschieden sein können in unseren verschiedenen Inkarnationen, die wir auf der Erde durchzumachen haben. Und überzeugt kann man auch sein, daß der, welcher die Welt so betrachtet, gerade durch eine solche Weltbetrachtung dazu kommt, daß er sagen muß: Ach, wie reich, wie grandios ist die Welt! Welches Glück, an ihr immer weiter, immer mehr, immer mannigfaltiger teilzunehmen, an ihrem Sein, ihren Wirkungen, ihrem Streben!

Third Lecture

Yesterday, I attempted to describe the nuances of worldview that are possible for human beings, in such a way that certain fully valid proofs of the correctness and truth of each of these nuances can be provided for a certain area. For those who are not intent on forging together into a system of concepts everything they have been able to observe and think through in a narrowly defined field, and then seeking proof for it, but rather for those who are intent on truly penetrating the truth of the world, it is important to know that this universality is necessary, which is expressed in the fact that the human mind is truly capable of twelve typical nuances of worldview—the transitions between them are not important here. If one really wants to arrive at the truth, one must attempt to clarify the meaning of these nuances of worldview and recognize in which areas of existence one or the other of these nuances of worldview provides the better key. If we once again consider these twelve nuances of worldview, as we did yesterday, we find that they are materialism, sensualism, phenomenalism, realism, dynamism, monadism, spiritualism, pneumatism, psychism, idealism, rationalism, and mathematicism.

Unfortunately, in the real world of human research for truth, it is the case that in individual minds, in individual personalities, the inclination toward one or the other of these nuances of worldview always predominates, and that as a result, the one-sidedness of the various worldviews of different epochs has an effect on people. What I have presented as the twelve main worldviews must be understood as something that can be truly grasped in such a way that one always places one worldview next to another in a circle and regards them as static. They are possible; one must know them. They really behave in such a way that they are a spiritual reflection of the zodiac, which is well known to us. Just as the sun appears to pass through the zodiac and other planets appear to pass through the zodiac, so it is possible for the human soul to pass through a spiritual circle containing twelve worldview images. Yes, one can even connect the peculiarities of these worldviews with the individual signs of the zodiac. And this connection is not arbitrary at all, but there really is a similar relationship between the individual zodiac signs and the earth as between these twelve worldviews and the human soul. This is meant in the following way.

At first glance, we cannot say that there is an easily understandable relationship between, for example, the zodiac image of Aries and the Earth. But when the Sun, Saturn, or Mercury are positioned so that they can be seen from Earth in the sign of Aries, they have a different effect than when they are positioned so that they can be seen in the sign of Leo. So the effect that comes to us from the cosmos, for example from the individual planets, differs depending on whether the individual planets cover one or the other sign of the zodiac. In the case of the human soul, it is even easier for us to recognize the influence of these twelve “spiritual zodiac signs.” There are souls that tend, as it were, to influence the configuration of their inner life, their scientific, philosophical, or other intellectual direction, in such a way that they allow themselves to be illuminated by idealism in their souls. Others allow themselves to be illuminated by materialism, others by sensualism. One is not a sensualist, materialist, spiritualist, or pneumatic because one view or another is correct and one can see the correctness of one view or another, but one is a pneumatic, spiritualist, materialist, or sensualist because one is so predisposed in one's soul that one is spiritually and soulfully illuminated by the relevant spiritual zodiac image. Thus, in these twelve spiritual zodiac images, we have something that can lead us deeply into the way in which human worldviews arise, and that can lead us deeply into the reasons why people, on the one hand, argue about worldviews, but on the other hand should not argue, but rather should understand why it is that people have different nuances of worldview. If it is nevertheless necessary in certain epochs to strictly reject one or the other worldview, we will have to explain the reason for this in tomorrow's lecture. What I have said so far therefore refers to the formation of human thought through the spiritual cosmos of the twelve spiritual zodiac images, which are, as it were, resting in our spiritual environment.

But there is something else that determines human worldviews. You will understand this best if I first show you the following.

One can be so attuned in one's soul, regardless of which of these twelve spiritual zodiac images shines upon one's soul, that one can describe this mood of the soul, which is expressed in the entire configuration of this soul's worldview, as gnosis. One can be a Gnostic. One is a Gnostic if one is inclined, through certain powers of knowledge lying in the soul itself, not through the senses or the like, to know the things of the world. One can be a Gnostic and, for example, have a certain inclination to be illuminated by the spiritual zodiac image that we have here called spiritualism. Then, in one's Gnosticism, one will be able to shine deeply into the connections of the spiritual worlds.

But one can also be, for example, a Gnostic of idealism; then one will have a special predisposition to see clearly the ideals of humanity and the ideas of the world. The difference between one person and another also exists in relation to the idealism that both people may have. One is an idealistic dreamer who always talks about being an idealist, who always has the word ideal, ideal, ideal on his lips, but who does not know many ideals, who does not have the ability to really call the ideals before his soul in sharp contours and with inner vision. Such a person differs from another who not only talks about ideals but knows how to paint them in his soul like a sharply painted picture. The latter, who grasps idealism quite concretely within himself, as intensely as one grasps external things with one's hand, is a Gnostic in the realm of idealism. One could also say that he is a Gnostic in general, but he allows himself to be illuminated in particular by the spiritual zodiac image of idealism.

There are people who are particularly strongly illuminated by the worldview of realism, but who go through life in such a way that, through the whole way they perceive the world and face it, they can tell other people a great deal about this world. They are neither idealists nor spiritualists; they are quite ordinary realists. They are capable of perceiving very finely what is in the external reality around them; they are finely attuned to the peculiarities of things. They are Gnostics, true Gnostics; only they are Gnostics of realism. Such Gnostics of realism exist, and sometimes spiritualists or idealists are not at all Gnostics of realism. We can even find that people who call themselves good theosophists can walk through a picture gallery and have nothing to say about the pictures, while others who are not theosophists at all, but who are gnostics of realism, know how to say infinitely meaningful things because they are in contact with the whole reality of things with their whole personality. Or how many theosophists go out into nature and do not know how to grasp the sublime and great in nature with their whole soul: they are not gnostics of realism. There are gnostics of realism. There are also gnostics of materialism. These are, however, strange gnostics. But in the same sense that one can be a Gnostic of realism, one can be a Gnostic of materialism; but these are people who have only meaning and feeling and sensation for everything material, who seek to know the material through direct contact, like the dog that sniffs substances and thereby gets to know them intimately and is actually an excellent Gnostic in relation to material things.

One can be a Gnostic for all twelve worldviews. That means, if we want to place Gnosis correctly, we must do so by drawing a circle and letting the whole circle signify that Gnosis can move through all twelve worldviews. Just as a planet moves through the twelve signs of the zodiac, so Gnosis can move through all twelve worldviews.

However, Gnosis will render the greatest service to the salvation of souls when the Gnostic attitude is applied to spiritualism. One could say that Gnosis is truly at home in spiritualism. It is in “its” home there. It is outside its home in the other worldviews. Logically, one has no right to say that there can be no materialistic Gnosticism. Pedants of terms and ideas find it easier to deal with such things than healthy logicians, who have a somewhat more complicated task. One could say, for example: I will call nothing Gnosis except that which enters the mind. This is an arbitrary definition, just as arbitrary as if someone were to say: I have only seen violets in Austria, so I only call violets what grows in Austria and has the color of violets, and nothing else. Logically, it is just as impossible to say that gnosis exists only in the worldview of spiritualism, because gnosis is a “planet” that passes through the constellations of the spirit.