Spiritual Wisdom in the Early Christian Centuries

GA 213

16 July 1922, Dornach

Translator Unknown

I have said on many occasions that at the time when medieval culture had reached its prime, two streams of spiritual life were flowing through the ripest souls in European civilisation—streams which I have described as knowledge through revelation and knowledge acquired by reason, as we find it in Scholasticism. Knowledge through revelation, in its more scholastic form, was by no means a body of mystical, abstract or indefinite thought. It expressed itself in sharply defined, clear-cut concepts. But these concepts were considered to be beyond the scope of man's ordinary powers of cognition and must in every case be accepted as traditions of the Church. The Church, by virtue of its continuity, claimed the right to be the guardian of this kind of knowledge.

The second kind of knowledge was held to be within the scope of research and investigation, albeit those who stood wholly within the stream of Scholasticism acknowledged that this knowledge acquired by reason could not in any sense be regarded as knowledge emanating from the super-sensible world.

Thus when medieval culture was at its prime, it was realised that knowledge no longer accessible to mankind in that age must be preserved as it were by tradition. But it was not always so, for if we go back through the Middle Ages to the first Christian centuries we shall find that the characteristics of this knowledge through revelation was less sharply emphasised than they were in medieval culture. If one had suggested to a Greek philosopher of the Athenian School, for instance, that a distinction could be made between knowledge acquired by reason and knowledge through revelation (in the sense in which the latter was understood in the Middle Ages), he would have been at a loss to know what was meant. It would have been unthinkable to him that if knowledge concerning super-sensible worlds had once been communicated to a man by cosmic powers, it could not be communicated afresh. True, the Greeks realised that higher spiritual knowledge was beyond the reach of man's ordinary cognition, but they knew too that by dint of spiritual training and through Initiation, a man could unfold higher faculties of knowledge and that by these means he would enter a world where super-sensible truth would be revealed to him.

Now a change took place in Western culture between all that lived in the centuries when Greek philosophy came to flower in Plato and Aristotle, and the kind of knowledge that made its appearance about the end of the fourth century A.D. I have often referred to one aspect of this change by saying that the Mystery of Golgotha occurred in an age when very much of the old Initiation-wisdom was still living in men. And indeed there were many who applied their Initiation-wisdom and were thus able, with super-sensible knowledge, to realise the significance of the Event on Golgotha. Those who had been initiated strained every nerve to understand how a Being like the Christ, Who before the Mystery of Golgotha had not been united with earthly evolution, had passed into an earthly body and linked Himself with the evolution of man. The nature of this Being, how He had worked before His descent to the earth—such were the questions which even at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha men were trying to answer by means of the highest faculties of Initiation-wisdom.

But then we find that from the fifth century A.D. onwards, this old Initiation-wisdom which had lived in Asia Minor, Northern Africa, in Greek culture, had spread over into Italy and still further into Europe, was less and less understood. People spoke contemptuously of certain individuals, saying that their teachings were to be avoided at all costs by true Christians. Moreover, efforts were made to obliterate all that had previously been known of these individuals.

It is strange that a man like Franz Brentano should have inherited from medieval tradition a hatred of all that lived in personalities like Plotinus, for example, of whom very little was known but who was regarded as one with whom true Christians could have no dealings. Brentano had allowed himself to be influenced by this hatred and vented it on Plotinus. He actually wrote a polemical thesis entitled Was für ein Philosoph manchmal Epoche macht, and the philosopher is Plotinus, who lived in the third century A.D. Plotinus lived within the streams of spiritual life which were wholly exhausted by the time of the fourth century A.D. and which in the later evolution of Christendom people tried to cast into oblivion.

The information contained in text-books on the history of philosophy in regard to the outstanding figures of the early Christian centuries is usually not only scanty in the extreme but quite incapable of giving any idea of their significance. Naturally it is difficult for us in modern times to have any true conception of the first three or four centuries of Christendom—for example, of the way in which the impulses living in Plato and Aristotle were working on and of thought which had in a certain respect become estranged from the deeper Mystery-wisdom, although this wisdom was still possessed by certain personalities in the first three or four centuries after the coming of Christ.

Very little real understanding of Plato is shown in modern text-books on the history of philosophy. Those of you who are interested should read the chapter on Plato in Paul Deussen's History of Greek Philosophy, and the passage where he speaks of the place assigned by Plato to the Idea of the Good in relation to the other Ideas. Deussen says something like this: Plato did not admit the existence of a personal God because, if he had done so, he could not have taught that the Ideas subsist in and through themselves. Plato could not acknowledge God as a Being because the Ideas are primary and subsistent. True—says Deussen—Plato places the Idea of the Good above the other Ideas, but he did not thereby imply that the Idea of the Good stands above the others.—For what is expressed in the Idea of the Good is, after all, only a kind of family-likeness which is present in all the Ideas.—Such is Deussen's argument.

But now let us scrutinise this logic more closely. The Ideas are there. They are subsistent and independent. The Idea of the Good cannot be said to rule or direct the other Ideas. All Ideas bear a family-likeness but this family-likeness is actually expressed through the Idea of the Good. Yes—but whence are family-likenesses derived? A family-likeness is derived from stock. The Idea of the Good points to family-likeness. What can we do except go back to the father of the stock!

This is what we find to-day in famous histories of philosophy and those who write them are regarded as authorities. People read such things and never notice that they are out-and-out nonsense. It is difficult to imagine that anyone capable of writing such absurdities in connection with Greek philosophy could have anything very valuable to say about Indian wisdom. Nevertheless, if we ask for something authoritative on the subject of Indian wisdom to-day we shall certainly be advised to read Paul Deussen. Things have come to a pretty pass!

My only object in saying this is to show that in the present age there is little real understanding of Platonic philosophy. Modern intellectualism is incapable of it. Nor is it possible to understand the tradition which exists in regard to Plotinus—the so-called Neo-Platonic philosopher Plotinus was a pupil of Ammonius Saccas who lived at the beginning of the third century A.D. It is said that Ammonius Saccas gave instruction to individual pupils but left nothing in writing. Now the reason why the eminent teachers of that age wrote nothing down was because they held that wisdom must be something living, that it could not be passed on by writing but only from man to man, in direct personal intercourse. Something else—again not understood—is said of Ammonius Saccas, namely that he tried to bring about agreement in the terrible quarrels between the adherents of Aristotle and of Plato, by showing that there was really no discrepancy between the teachings of Plato and Aristotle.

Let me try to tell you in brief words how Ammonius Saccas spoke of Plato and Aristotle. He said: Plato belonged to an epoch when many human souls were treading the path to the spiritual world in other words when there was still knowledge of the principles of true Initiation. But in more ancient times there was no such thing as abstract, logical thought. Even now (at the beginning of the third century A.D.) only the first, elementary traces of this kind of thinking are making their appearance. In Plato's time, thoughts evolved independently were unknown. Whereas the Initiates of earlier times gave their message in pictures and imaginations, Plato was one of the first to change these imaginations into abstract concepts and ideas. The great spiritual picture to which Plato tried to lift the eyes of men was brought down in more ancient times merely in the form of imaginations. In Plato, the imaginations were already concepts—but these concepts poured down as it were from the world of Divine Spirit. Plato said in effect: the Ideas are the lowest revelation of the Divine-Spiritual. Aristotle could no longer penetrate with the same intensity into this spiritual substance. Therefore the knowledge he possessed only amounted to the substance of the ideas, and this is at a lower level than the picture itself. Nevertheless, Aristotle could still receive the substance of the ideas in the form of revelation. There is no fundamental difference between Plato and Aristotle—so said Ammonius Saccas—except that Plato was able to gaze into higher levels of the spiritual world than Aristotle.—And thereby Ammonius Saccas thought to reconcile the disputes among the followers of Aristotle and Plato.

We learn, then, that by the time of Plato and Aristotle, wisdom was already beginning to assume a more intellectual form. Now in those ancient times it was still possible for individuals here and there to rise to very high levels of spiritual perception. The lives of men like Ammonius Saccas and his pupil Plotinus were rich in spiritual experiences and their conceptions of the spiritual world were filled with real substance.

Naturally one could not have spoken to such men of outer Nature in the sense in which we speak of Nature to-day. In their schools they spoke of a spiritual world, and Nature—generally regarded nowadays as complete and all-embracing—was merely the lowest expression of that spiritual world of which they were conscious.

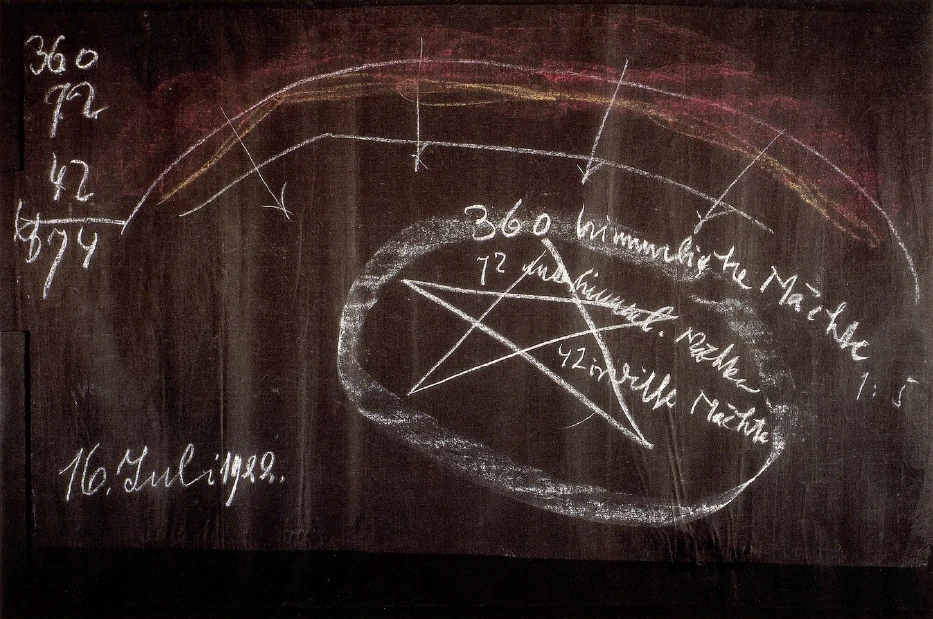

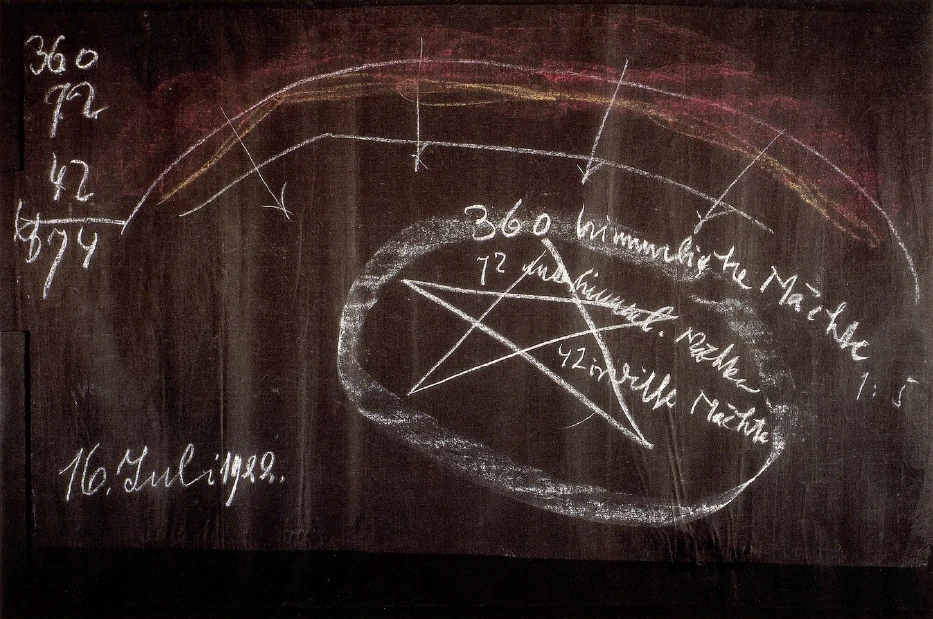

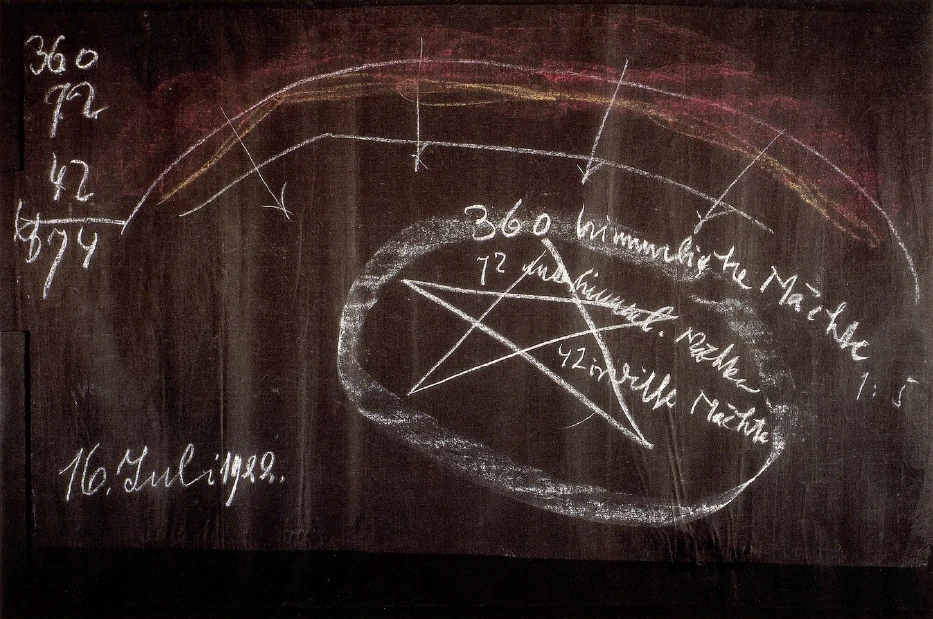

We can form some idea of how such men were wont to speak, if we study Iamblichus, a man possessed of deep insight and one of the successors of Ammonius Saccas. How did the world appear to the soul of Iamblichus? He spoke to his pupils somewhat as follows:—If we would understand the universe let us not pay heed to space, for space contains merely the outward expression of the spiritual world. Nor let us pay heed to time, for only the illusory images of cosmic reality arise in time. Rather must we look up to those Powers in the spiritual world who are the Creators of time and of the connections between time and space. Gazing out into the expanses of the cosmos, we see how the cycle, repeated visibly in the Sun, repeats itself every year. But the Sun circles through the Zodiac, through the twelve constellations. It is not enough merely to observe this phenomenon, for three hundred and sixty heavenly Powers are working and weaving therein, sending forth the Sun-forces which flood the whole universe accessible to man. Every year the cycle is repeated. If these Powers alone held sway, there would be three hundred and sixty days in a year. But there are, in fact, five additional days, ruled by seventy-two sub-heavenly Powers, the planetary Spirits. I will draw (on the blackboard) this pentagonal figure, because one to five is the relation of seventy-two to three hundred and sixty. The five remaining days in the cosmic year which are abandoned, as it were, by the three hundred and sixty heavenly Powers, are ruled by the seventy-two sub-heavenly Powers. But over and above the three hundred and sixty-five days, there are still a few more hours in the year. And these hours are directed by forty-two earthly Powers.—Iamblichus also said to his pupils: The three hundred and sixty heavenly Powers are connected with the head-organisation of man, the seventy-two sub-heavenly Powers with the breast-system (breathing-process and heart) and the forty-two earthly Powers with the purely earthly system in man (e.g. digestion, metabolism).

In those times the human being was given his place in a spiritual universe, whereas nowadays we begin our physiological studies by learning of the quantities of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorus, lime-stone, etc., within the human organism. We relate the human being to a lifeless nature. But Iamblichus would have taught how the organism of man is related to the forty-two earthly Powers, the seventy-two sub-heavenly or planetary Powers, and the three hundred and sixty heavenly Powers. Just as to-day man is said to be composed of earthly substances, in the time of Iamblichus he was known to represent a confluence of forces streaming from the spiritual universe. Great and sublime was the wisdom presented in the schools of learning in those days, and one can readily understand that Plotinus—who had reached the age of twenty-eight before he listened to the teachings of Ammonius Saccas—felt himself living in an altogether different world. He was able to assimilate some of this wisdom because it was still cultivated in many places during the first four centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha. With this wisdom men also tried to understand the descent of the Christ into Jesus of Nazareth and the place of Christ in the realms of the spiritual Hierarchies, in the great structure of the spiritual universe.

And now let me deal with another chapter of the wisdom taught by Iamblichus. He said: There are three hundred and sixty heavenly Powers, seventy-two planetary Powers, forty-two earthly Powers—in all, four hundred and seventy-four Divine Beings of different orders. Look to the far East—so said Iamblichus—and you will there find peoples who give names to their Gods. Turn to the Egyptians and to other peoples—they too name their Gods. Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans—all will name their Gods. The four hundred and seventy-four Gods include all the Gods of all the different peoples: Zeus, Apollo, Baal—all the Gods. The reason why the peoples have different Gods is that one race has chosen twelve or maybe seventeen Gods from the four hundred and seventy-four, another race has taken twenty-five, another three, another four. The number of racial Gods is four hundred and seventy-four. And the highest of these Gods, the God who came down to earth at a definite point of time, is Christ.

This wisdom was well suited to bring about reconciliation between the different religions, not as the outcome of vague sentiment but of the knowledge that the different Gods of the peoples constitute, in their totality, one great system—the four hundred and seventy-four Gods. It was taught that all the choirs of Gods of the peoples of ancient times had reached their climax in Christianity and that the crown of wisdom was to understand how the Christ Being had entered through Jesus of Nazareth into His earthly activity.

And so, as we look back to an earlier Spiritual Science (which although it no longer exists in that form to-day, indeed cannot do so for it must be pursued now-a-days in a different way), the deepest respect grows up within us. Profound wisdom was taught in the early Christian centuries in regard to the super-sensible worlds. But knowledge of this spiritual universe was imparted only to those who were immediate pupils of the older Initiates. The wisdom might only be passed on to those whose faculties of knowledge had reached the stage where they were able to understand the essence and being of the different Gods.

This requisite of spiritual culture was recognised everywhere in Greece, in Egypt and in Asia Minor. It is, of course, true, that remnants of the ancient wisdom still existed in Roman civilisation. Plotinus himself taught for a long time in Italy. But a spirit of abstraction had crept into Roman culture, a spirit no longer capable of understanding the value and worth of personality, of being. The spirit of abstraction had crept in, not yet in the form it afterwards assumed, but adhered to all the more firmly because it was there in its earliest beginnings.

And then, on the soil of Italy at the beginning of the fourth century A.D. we find a School which began to oppose the ancient principle of Initiation, the preparation of the individual for Initiation. We see a School arising which gathers together and makes a careful record of everything originating from ancient Initiation-wisdom. The aim of this School—which lasted beyond the third on into the fourth century—was to perpetuate the essence of Roman culture, to establish historical tradition as against the strivings of individual human Beings. As Christianity began to find its way into Roman culture, the efforts of this school were directed to the elimination of all that could still have been discovered by means of the old Initiation-knowledge in regard to the presence of Christ in the personality of Jesus.

It was a fundamental tenet of this Roman School that the teaching given by Ammonius Saccas and Iamblichus must not be allowed to pass on to posterity. Just as in those times there was a widespread impulse to destroy the ancient temples and altars—in short to obliterate every remnant of ancient Heathendom—so, in the domain of spiritual life, efforts were made to wipe out the principles whereby knowledge of the higher world might be attained. To take one example: the dogma of the One Divine Nature or of the Two Divine Natures in the Person of Christ was substituted for the teaching of Ammonius Saccas and Iamblichus, namely, that the individual human being can develop to a point where he will understand how the Christ took up His abode in the body of Jesus. This dogma was to reign supreme and the possibility of individual insight smothered. The ancient path of wisdom was superseded by dogma in the culture of the Roman world. And because strenuous efforts were made to destroy any teaching that savoured of the ancient wisdom, little more than the names of men like Ammonius Saccas and Iamblichus have come down to us. Of many other teachers in the Southern regions of Europe not even the names have been preserved. Altars were destroyed, temples burnt to the ground and the ancient teachings exterminated, to such an extent indeed that we have no longer any inkling to-day of the wisdom that lived in the South of Europe during the first four centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha.

Again and again it happened, however, that knowledge of this wisdom found its way to men who were interested in these matters and who realised that Roman culture was rapidly falling to pieces under the spread of Christianity. But after the extermination of what would have been so splendid a preparation for an understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha, it was only possible to learn of the union of Christ with Jesus in the form of an abstract dogma laid down by the Councils and coloured by the Roman spirit. The living wisdom was wiped out, and abstraction, albeit working on in the guise of revelation, took its place.

History is well-nigh blank in regard to these things, but during the first centuries of Christendom there were a number of men who were able to say: “There are indeed Initiates—of whom Iamblichus was one. It is the Initiates who teach true Christianity. To them, Christ is Christ indeed, whereas the Romans speak merely of the ‘Galileans.’ ” This expression was used in the third and fourth centuries A.D. to gloss over a deep misunderstanding. The less men understood Christianity, the more they spoke of the Galileans; the less they knew of the Christ, the more emphasis they laid on the human personality of the ‘Galilean.’

Out of this milieu came Julian, the so-called Apostate, who had absorbed a very great deal from pupils of men like Iamblichus and who still knew something of the spiritual universe reaching down into every phenomenon of Nature. Julian the Apostate had heard from pupils of Iamblichus of the spiritual forces working down into every animal and plant from the three hundred and sixty heavenly Powers, the seventy-two planetary Powers and the forty-two earthly Powers. In those days there were still some who understood what was, for example, expressed in a most wonderful way in a deeply significant legend related of Plotinus. The legend ran: There were many who would no longer believe that a man could be inspired by the Divine Spirit and who said that anyone who claimed to have knowledge of the Divine-Spiritual world was possessed by a demon. Plotinus was therefore carried off to the temple of Isis in Egypt in order that the priests might determine the nature of the demon possessing him. And when the Egyptian priests—who still had knowledge of these things—came to the temple and tested Plotinus before the altar of Isis, performing all the ritual acts still possible at that time, Lo! instead of a demon there appeared the Godhead Himself!

This legend indicates that in those times men still acknowledged that at least it was possible to prove whether a good God or a demon was possessing a human being.

Julian the Apostate heard of these things. But on the other side there came insistently to his ears the words of a writing which passed into many hands in the Roman world during the first Christian centuries and was said to be a sermon of the Apostle Peter, whereas it was actually a forgery. In this document it was said: Behold the godless Hellenes! In very creatures of nature they see the Divine-Spiritual. This is sinful, impious. It is sacrilege to see the Divine-Spiritual in Nature, in animal and in plant. Let no man be so sinful as to believe that the Divine is present in the course of the Sun and Moon.—These were the things that dinned in the ears of Julian, now from one side, now from another. A deep love for Hellenism grew up within him and he became the tragic figure who would fain have spoken of Christianity in the light of the teachings of Iamblichus.

There is no telling what would have come to pass in Europe if the Christianity of Julian the Apostate had conquered instead of the doctrines of Rome, if his desire to restore the Initiation-training had been fulfilled the training whereby men could themselves have attained to knowledge of how the Christ had lived in Jesus and of His place among the other racial Gods. Julian the Apostate was not out to destroy the heathen temples. Indeed he would have been willing to restore the temple of the Jews at Jerusalem. His desire was to restore the heathen temples and he also had the interests of the Christians at heart. Truth and truth alone was his quest. And the great obstacle in his way was the School in ancient Rome of which I have spoken—the School which not only set out to exterminate the old principle of Initiation but did in fact succeed in exterminating it, wishing to put in its place recorded traditions of Initiation-wisdom.

When the moment had arrived, it was easy to arrange for the thrust of the Persian spear which caused Julian's death. It was then that the words were uttered which have never since been understood, not even by Ibsen, but which can be explained by a knowledge of the traditions of Julian's time: ‘The Galilean has conquered, not the Christ!’ For at this moment of death it was revealed to the prophetic vision of Julian the Apostate that henceforward the conception of Christ as a Divine Being would fade away and that the ‘Galilean,’ the man of Galilean stock would be worshipped as a God. In the thirtieth year of his life Julian the Apostate had a pre-vision of the whole of subsequent evolution, on into the nineteenth century, by which time theology had lost all knowledge of the Christ in Jesus.

Julian was ‘Apostate’ only in regard to what was to come after. The Apostate was indeed the Apostle in respect of spiritual realisation of the Mystery of Golgotha.—And it is this spiritual realisation that must be quickened again in the souls of men.

Newer geological strata always overlay those that are older and the newer must be pierced before we can reach those that lie below. It is sometimes difficult to believe beneath what thick layers the history of human evolution lies concealed. Thick indeed are the layers spread by Romanism over the first conceptions of the Mystery of Golgotha! Through spiritual knowledge it must again be possible to penetrate through these layers and so rediscover that old wisdom which was swept away from the domain of spiritual life just as the heathen altars were swept away from the physical world.

Egyptian priests declared that Plotinus bore a God within him, not a demon. But in the West the dictum went forth that Plotinus was assuredly possessed by a demon. Read what has been said on the subject, including the thesis by Brentano which I have mentioned, and you will find the same. According to the Egyptian priests, a God and not a demon was living in Plotinus, the philosopher of the third century A.D. But Brentano states the contrary. He declares: Plotinus was possessed by a demon, not by a God!

And then, in the nineteenth century, the Gods became demons, the demons Gods. Men were no longer capable of distinguishing between Gods and demons in the universe. And this has lived on in the chaos of our civilisation.

Truly these things are grave when we see them as they really are. I wished to-day to speak of one chapter of history and from an absolutely objective standpoint, for what comes to pass in history is after all inevitable. Necessary as it was that for a season men should remain without enlightenment about certain mysteries, enlightenment must ultimately be given, and—what is more—received.

Elfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich mußte während der letzten Betrachtung wiederholt darauf aufmerksam machen, wie in der Blütezeit des Mittelalters innerhalb der europäischen Zivilisation zwei Geistesströmungen durch die besten Seelen gehen, jene beiden Geistesströmungen, die ich gestern genauer charakterisierte als die Offenbarungserkenntnis und die Vernunfterkenntnis innerhalb der Scholastik. Nun mußten wir ja betonen, daß die Offenbarungserkenntnis in dem Sinne, wie sie innerhalb der Scholastik auftritt, durchaus nicht irgend etwas mystisch oder abstrakt Unbestimmtes ist, sondern daß sie ein Erkenntnisinhalt ist, der in scharf konturierten, scharf geformten Begriffen auftritt. Nur daß man diesen Begriffen nicht zugesteht, daß sie unmittelbar in menschlicher Erkenntnis gefunden werden können, sondern darauf aufmerksam macht, daß sie von jedem einzelnen, der in ihren Besitz gelangen soll, aus der Überlieferung der Kirchen genommen werden müssen, die eben in ihren Überlieferungen und in ihrem kontinuierlichen Fortbestand das Recht haben, solchen Erkenntnisinhalt gewissermaßen aufzubewahren.

[ 2 ] Der zweite Erkenntnisinhalt war dem menschlichen Forschen, dem menschlichen Streben freigegeben; aber es mußten diejenigen, die nun wirklich innerhalb der wahren scholastischen Richtung drinnenstanden, anerkennen, daß mit diesem Vernunfterkenntnis-Inhalt keinerlei Erkenntnis aus der übersinnlichen Welt erlangt werden kann.

[ 3 ] Damit ist also in der geistigen Blüte des Mittelalters zugegeben, daß gewissermaßen dasjenige historisch erhalten werden mußte an Erkenntnis, was den Menschen für die damalige Gegenwart nicht mehr zugänglich war. Ich habe aber auch schon angedeutet, daß es nicht immer so war. Wenn wir weiter zurückgehen, das Mittelalter hindurch bis in die ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte, dann finden wit, daß dieser besondere Charakter der Offenbarungserkenntnis nicht schon in gleich scharfer Weise betont wird, wie das im späteren Mittelalter der Fall war. Und wenn man etwa einem Griechen, sagen wir der athenischen Philosophenschule, so etwas vorgehalten hätte wie eine Trennung der Erkenntnis nach einer bloßen Vernunfterkenntnis und einer nur durch Offenbarung gegebenen Erkenntnis — die Offenbarung in dem Sinne genommen, wie sie im Mittelalter genommen worden ist —, so würde der griechische Philosoph das eben gar nicht verstanden haben. Er hätte keinen Begriff damit verbinden können, daß, wenn einmal durch außerweltliche Macht dem Menschen ein Erkenntnisinhalt über das Übersinnliche mitgeteilt worden ist, der dann bleiben sollte, er nicht neuerdings wiederum mitgeteilt werden könnte. Der Grieche verstand, daß man nicht durch die gewöhnliche Erkenntnismethode zu dem höheren geistigen Inhalte kommen könne; allein er verstand es so, daß man von den Erkenntnisfähigkeiten, die man nun einmal als Mensch hat, durch geistige Schulung, durch den Weg der Initiation aufsteigen kann zu höheren Erkenntnisfähigkeiten. Dann tritt man eben in diejenige Welt ein, in der man zu schauen vermag, was für das Übersinnliche die Wahrheit, die Erkenntnis ist.

[ 4 ] Und gerade mit Bezug auf diese Sache ist für das ganze abendländische Zivilisationsleben eine Wendung eingetreten zwischen dem, was in den Jahrhunderten vorhanden war, in denen die griechische Philosophie in Plato, in Aristoteles noch geblüht hat, und dem, was dann aufgetreten ist etwa am Ende des 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts. Ich habe ja die eine Seite dieser Sache schon öfter betont. Ich habe betont: Das Ereignis von Golgatha ist in einer Zeit geschehen, in welcher noch viel von alter Initiationsweisheit, alter Initiationserkenntnis vorhanden war. Und wahrhaftig, genügend viele Leute haben die alte Initiationsweisheit angewendet, um aus ihrer Initiation heraus das Golgatha-Ereignis mit den Mitteln der übersinnlichen Erkenntnis zu begreifen. Initiierte bemühten sich, alles, was sie zusammentragen konnten an Initiationserkenntnis, aufzuwenden, um zu verstehen, wie eine solche Wesenheit wie der Christus, der vor der Zeit des Golgatha-Mysteriums nicht mit der irdischen Entwickelung vereinigt war, sich mit einem irdischen Leib verbindet und nun mit der menschlichen Entwickelung vereinigt bleibt. Was das für ein Wesen ist, wie diese Wesenheit sich verhalten hat, bevor sie heruntergestiegen ist in das Irdische, alles das waren Fragen, zu deren Beantwortung man höchste Initiationsfähigkeiten auch zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha anwendete.

[ 5 ] Nun aber sehen wir, daß die alte Initiationsweisheit, die in Vorderasien, in Nordafrika, auch innerhalb der hellenischen Kultur durchaus vorhanden war und sich auch nach Italien herüber, sogar weiter noch nach Europa herein erstreckte, daß diese Initiationsweisheit vom 5. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert an überhaupt immer weniger und weniger verstanden wird. Man redete dann von einzelnen Namen so, daß man die Träger dieser Namen innerhalb der christlichen Zivilisation des Abendlandes als ziemlich verächtliche Persönlichkeiten hinstellte, mindestens als Persönlichkeiten, mit denen sich ein richtiger Christ nicht befassen sollte. Man bestrebte sich aber auch, möglichst die Spuren alles früheren Wissens von dem, was eigentlich in solchen Persönlichkeiten war, zu verwischen.

[ 6 ] Es ist merkwürdig, daß eine Persönlichkeit wie Franz Brentano aus seiner mittelalterlichen Tradition heraus für seine eigene Seele noch durchaus den Haß gegen alles das erbte, was damals in Persönlichkeiten wie zum Beispiel PJozin lebte, von dem ja auch außerordentlich wenig gewußt wurde, der aber als ein Philosoph angesehen wurde, mit dem sich ein richtiger christlicher Bekenner nicht befassen sollte. Brentano teilte diesen Haß auf Plotin. Er hat ihn auf sich vererben lassen. Er hat eine Abhandlung geschrieben: «Was für ein Philosoph manchmal Epoche macht», und er meinte damit Plotin, den Philosophen des 3. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts, der in jenen Geistesströmungen drinnen stand, die eigentlich mit dem 4. Jahrhundert dann vollständig versiegten und an die man in der späteren christlichen Entwickelung keine Erinnerung bewahren wollte.

[ 7 ] Was in den gebräuchlichen Geschichtsphilosophien über sehr hervorragende Geister jener Zeit der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte gesagt wird, das ist ja zumeist nicht etwa nur das Notdürftigste, sondern es ist so, daß nicht im geringsten eine zusammenhängende Vorstellung über diese Geister daraus gewonnen werden kann. Es ist ja natürlich, daß es auch in der Gegenwart noch große Schwierigkeiten bereitet, sich über die drei oder vier ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte eine ordentliche Vorstellung zu machen. So zum Beispiel über die Art und Weise, wie das, was bei Plato und Aristoteles vorhanden war, fortgewirkt hat, und was ja ohnedies schon in einem gewissen Sinne entfremdet war der tieferen Weisheit der Mysterien, in deren Besitz aber solche Persönlichkeiten, wie ich sie meine, in den ersten drei bis vier christlichen Jahrhunderten noch waren. Es ist ja heute eigentlich kaum eine ordentliche Plato-Erkenntnis in den gebräuchlichen Geschichten der Philosophie vorhanden. Wenn Sie sich dafür interessieren, so schlagen Sie sich doch zum Beispiel das Kapitel über Plato in der Geschichte der griechischen Philosophie von Paul Deussen auf, wo Deussen davon spricht, wie eigentlich Plato über die Idee des Guten im Verhältnisse zu den anderen Ideen gedacht hat. Da können Sie Sätze finden wie diesen: Plato nahm einen persönlichen Gott nicht an, sonst wären die Ideen, die er annahm, ja nicht durch sich selbständig gewesen; Plato konnte einen wesenhaften Gott nicht anerkennen, weil die Ideen selbständig sind. - Allerdings, sagt Deussen, setzt Plato wiederum die Idee des Guten über die anderen Ideen. Allein | das soll nicht heißen, daß die Idee des Guten als irgend etwas wesenhaft Selbständiges über den anderen Ideen stehe; denn, was die Idee des Guten ausdrücke, das sei nur eine gewisse Familienähnlichkeit, die in allen Ideen vorhanden sei.

[ 8 ] Bitte, setzen Sie sich jetzt einmal ordentlich auf Ihre Stühle und schauen Sie sich Deussens Logik, diese Logik eines hervorragenden Philosophen der Gegenwart, genauer an. Da hat Plato die Ideen. Die sind selbständig. Jetzt hat Plato auch noch die Idee des Guten. Die darf aber nicht irgend etwas sein, was die anderen Ideen dirigiert, sondern die Ideen haben untereinander eine Familienähnlichkeit. Durch die Idee des Guten wird nur die Familienähnlichkeit ausgedrückt. Ja aber, woher kommen denn Familienähnlichkeiten? Wenn irgendwo eine Familienähnlichkeit ist, so kommt sie doch von der Abstammung von einem Übergeordneten mindestens, wenn man den Ausdruck gebrauchen wollte. Die Idee des Guten, die weist auf eine Familienähnlichkeit; also müßte man ja erst recht an den Stammvater herankommen!

[ 9 ] Ja, das steht in hervorragenden Philosophiegeschichten der Gegenwart! Die Menschen, die so etwas schreiben, werden Autoritäten in der Gegenwart. Die Leute lernen das und merken nicht, daß es der reine Unsinn ist. Man kann natürlich jemandem, der solch einen Unsinn redet über die griechische Philosophie, auch nicht zutrauen, daß er sehr viel über die indische Weisheit zu sagen hat. Aber dennoch, wenn Sie heute irgendwo etwas Autoritatives über die indische Weisheit suchen, so wird auf Paul Deussen gedeutet. Die Dinge sind schon schlimm.

[ 10 ] Ich wollte damit nur sagen, daß gegenwärtig auch für das Auffassen der Platonischen Philosophie selbst nicht viel Sinn vorhanden ist. Der gegenwärtige Intellektualismus ist eben dazu sehr wenig imstande. Daher kann auch so etwas nicht verstanden werden, was immerhin wenigstens noch zu den Überlieferungen gehört. Das ist, daß Plotin, der neuplatonische Philosoph — so nennt man ihn ja immer -, ein Schüler war des Ammonius Sakkas, der im Beginne des 3. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts gelebt hat, aber nichts geschrieben, sondern nur einzelne Schüler unterrichtet hat. Geschrieben haben die hervorragendsten Geister gerade dieser Zeit überhaupt nichts, weil sie der Meinung waren, daß der Weisheitsinhalt als ein Lebendiges da sein müsse, daß er nicht übertragen werden könne durch die Schrift von dem einen auf den anderen, daß er nur von Mensch zu Mensch im unmittelbaren persönlichen Verkehr übertragen werden müsse. Nun wird von Ammonius Sakkas noch eines erzählt, dessen Bedeutung den Leuten wiederum nicht klar wird. Es wird erzählt, daß er sich bemühte, gegenüber den schrecklichen Streitereien der Anhänger des Aristoteles und der Anhänger Platos Einigkeit zu erzielen, indem er zeigte, wie eigentlich Plato und Aristoteles durchaus in Harmonie miteinander stehen.

[ 11 ] Ich möchte Ihnen einmal nur in wenigen Strichen charakterisieren, wie dieser Sakkas etwa über Plato und Aristoteles gesprochen haben könnte. Er charakterisierte seinerseits: Plato gehörte noch demjenigen Zeitalter an, in welchem viele Menschen ihren unmittelbaren Seelenweg hinauf in die geistige Welt fanden, mit anderen Worten, in welchem die Menschen das Initiationsprinzip noch gut kannten. Aber in älteren Zeiten, so mag etwa Ammonius Sakkas gesagt haben, war das logisch-abstrakte Denken gar nicht entwickelt. Davon sind nur die ersten Spuren jetzt vorhanden — ich meine «jetzt» im Beginne des 3, nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts. Gedanken, von Menschen ausgebildet, gab es eigentlich auch noch zu Platos Zeiten nicht. Aber während ältere Initiierte alles das, was sie den Menschen zu geben hatten, nur in Bildern, in Imaginationen gaben, war Plato einer der ersten, welcher die Imaginationen umwandelte in abstrakte Begriffe. Wenn man sich den mächtigen Bildinhalt vorstellt (rot), zu dem auch Plato den Menschen hinaufschauen lassen wollte, so war es durchaus so, daß sich für ältere Zeiten dieser Bildinhalt eben bloß in Imaginationen ausdrückte (orange), aber für Plato schon in Begriffen (weiß). Aber diese Begriffe strömten gewissermaßen aus dem göttlich-geistigen Inhalt herunter (Pfeile). Plato sagte: Die unterste Offenbarung, gewissermaßen die verdünnteste Offenbarung des göttlich-geistigen Inhaltes, sind die Ideen, Aristoteles hatte nicht mehr eine so intensive Möglichkeit, sich zu diesem geistigen Inhalt hinaufzuheben. Daher hatte er gewissermaßen nur das, was unterhalb des Bildinhaltes war, er hatte nur den Ideengehalt. Aber den konnte er noch als einen geoffenbarten auffassen. Es ist kein Unterschied zwischen Plato und Aristoteles, so sagte etwa Sakkas, als allein der, daß Plato höher hinaufschaute in die geistige Welt, und Aristoteles weniger hoch hinaufschaute in die geistige Welt.

[ 12 ] Damit glaubte Ammonius Sakkas die Streitigkeiten hinwegzufegen, die unter den Anhängern des Aristoteles und des Plato vorhanden waren. Und wenn sich auch der Weisheitsgehalt schon unter Plato und Aristoteles dem intellektualistischen Auffassen näherte, so waren immerhin in jenen alten Zeiten noch Möglichkeiten vorhanden, daß der eine oder der andere Mensch auch wirklich in persönlicher Erfahrung sehr weit in die Region des geistigen Schauens hinaufkam. Und so muß man sich schon vorstellen, daß solche Menschen, wie Ammonius Sakkas und sein Schüler Plotin, in der Tat noch voll von inneren unmittelbaren Geist-Erlebnissen waren und vor allen Dingen solche Geist-Erlebnisse hatten, daß bei ihnen die Anschauung über die geistige Welt einen vollkonkreten Inhalt hatte. Man hätte natürlich solchen Menschen nicht von einer äußeren Natur sprechen können, wie man es heute tut. Solche Menschen haben in ihren Schulen von einer geistigen Welt gesprochen, und die Natur unten, die heute vielen als das Ein und Alles gilt, war nur der unterste bildliche Ausdruck für das, was ihnen als geistige Welt bewußt war. Wie solche Menschen sprachen, davon kann man eine Vorstellung geben, wenn man einen der Nachfolger des Sakkas betrachtet, der noch tiefe Einsichten hatte und diese in das 4. Jahrhundert hinübertrug: Jamblichos.

[ 13 ] Stellen wir einmal das Weltbild des Jamblichos vor unsere Seele. Er hat etwa in der folgenden Weise zu seinen Schülern gesprochen. Er sagte: Will man die Welt verstehen, so darf man nicht auf den Raum schauen, denn im Raume ist nur der äußere Ausdruck der geistigen Welt vorhanden. Man darf auch nicht auf die Zeit schauen, denn in der Zeit spielt sich bloß die Illusion von dem ab, was wirklicher, wahrer Welteninhalt ist. Man muß aufschauen zu denjenigen Mächten in der geistigen Welt, welche die Zeit und den Zusammenhang der Zeit mit dem Raum gestalten. Man schaue hinaus in das ganze Weltenall. Alljährlich wiederholt sich der Kreisgang, der sich sichtbarlich äußerlich in der Sonne ausdrückt. Aber diese Sonne kreist durch den Tierkreis, durch die 12 Sternbilder. Das soll man nicht nur anglotzen. Denn in dem wirken und weben 360 himmlische Mächte, und sie sind es, die alles das bewirken, was im Laufe eines Jahres an Sonnenwirksamkeit ausgeht für die ganze den Menschen zugängliche Welt, und sie wiederholen den Zyklus in jedem Jahre. Wenn sie allein regierten, so würde das Jahr 360 Tage haben -, so etwa hatte Jamblichos seinen Schülern gesagt. Aber da bleiben 5 Tage übrig. Diese 5 Tage sind von 72 unterhimmlischen Mächten, den Planetengeistern, dirigiert. Ich zeichne dieses Fünfeck in den Kreis, weil ja 72 zu 360 sich verhält wie 1 zu 5. Die 5 übrigbleibenden Weltentage des Jahres, in denen also gewissermaßen die 360 himmlischen Mächte eine leere Zeit lassen würden, die werden dirigiert von den 72 unterhimmlischen Mächten. Nun wissen Sie ja, daß das Jahr nicht bloß 365 Tage, sondern noch einige Stunden mehr hat; für diese Stunden sind nach Jamblichos 42 irdische Mächte da.

[ 14 ] Weiter sagte Jamblichos zu seinen Schülern: Die 360 himmlischen Mächte hängen zusammen mit allem, was menschliche Hauptesorganisation ist. Die 72 unterhimmlischen Mächte hängen zusammen mit allem, was Brustorganisation, Atmungs- und Herzorganisation ist, und die 42 irdischen Mächte hängen zusammen mit all dem, was im Menschen die rein irdische Organisation der Verdauung, des Stoflwechsels und so weiter ist.

[ 15 ] So wurde der Mensch hineingestellt in ein geistiges System, in ein geistiges Weltsystem. Heute beginnen wir unsere Physiologien damit, daß wir auseinandergesetzt bekommen, wieviel der Mensch an Kohlenstoff, an Wasserstoff, Stickstoff, Schwefel, Phosphor, Kalk und so weiter aufnimmt. Wir setzen den Menschen in Beziehung zu dem, was leblose Natur ist. Jamblichos würde in seinen Schulen den Menschen dargestellt haben, wie er zu den 42 irdischen, zu den 72 zwischenhimmlischen oder planetarischen und zu den 360 himmlischen Mächten steht. Wie heute der Mensch dargestellt wird als etwas, was aus den Stoffen der Erde zusammengesetzt ist, so wurde der Mensch dazumal dargestellt als etwas, was herunterfließt aus den Kräften, aus den Agenzien des geistigen Weltenalls. Man kann nur sagen, es war eine ungeheure, eine hohe Weisheit, welche damals in diesen Schulen vertreten worden ist. Man kann begreifen, daß Plotin, der erst im achtundzwanzigsten Lebensjahre dazu gekommen ist, ein Zuhörer des Ammonius Sakkas zu werden, sich wie in einer anderen Welt fühlte, weil er fähig war, etwas von dieser Weisheit aufzunehmen. Und diese Weisheit wurde noch an vielen Stätten in den ersten vier Jahrhunderten nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha gepflegt. Mit dieser Weisheit versuchte man auch zu verstehen, wie der Christus heruntergekommen war zum Jesus von Nazareth. Man versuchte zu verstehen, wie der Christus sich in diese ganze mächtige Welt geistiger Hierarchien, in dieses geistige Weltengebäude hineinstellt.

[ 16 ] Und nun will ich noch ein Kapitel der Jamblichos-Weisheit, die er in seinen Schulen vortrug, behandeln. Er sagte: Da sind also 360 himmlische Mächte, da sind 72 planetarische Mächte und 42 irdische Mächte. Da sind also im ganzen 474 göttliche Wesenheiten der verschiedensten Rangordnungen. Ihr könnt nun, so sagte Jamblichos zu seinen Schülern, nachschauen im fernsten Osten, da werdet ihr sehen, daß es dort Völker gibt, die euch ihre Götternamen nennen. Dann geht ihr zu den Ägyptern, die nennen euch wiederum ihre Götternamen, zu anderen Völkern, auch diese nennen euch ihre Götternamen. Dann geht ihr zu den Phöniziern, dann zu den Hellenen, wiederum findet ihr Götternamen. Und geht ihr hinüber zu den Römern, wieder findet ihr Götternamen. Wenn ihr die 474 Götternamen nehmt, so sind alle diese verschiedenen Götter der verschiedenen Völker darinnen: Zeus, Apollo, auch Baal, Amon, der ägyptische Gott, alle Götter gehören zu diesen 474. Daß die Völker verschiedene Götter haben, das liegt nur daran, daß das eine Volk sich von den 474 Göttern 12 oder 17 herausgenommen hat, das andere 20 oder 25, das andere Volk 3, 4 und so weiter. Aber wenn man diese verschiedenen Gottheiten der verschiedenen Völker richtig versteht, dann bekommt man 473 heraus. Und der höchste, der vornehmste, derjenige, der in einer bestimmten Zeit zur Erde niedergekommen ist, das ist der Christus.

[ 17 ] Es war gerade in dieser Weisheit eine tiefe Tendenz, Frieden zu stiften unter den verschiedensten Religionen, aber nicht aus einem unbestimmten Gefühl heraus, sondern indem man erkennen wollte, wie eben für den, der aus dem Weltengebäude heraus die 474 Götter wirklich kennenlernte, die verschiedenen Gottheiten der verschiedenen Völker sich einreihten in ein großes System, und man hat den ganzen Götterolymp aller Völker der alten Zeit so verstehen wollen, daß das alles in dem Christentum gipfelte. Gekrönt werden sollte dieses Gebäude davon, daß eben verstanden werden sollte, wie der Christus im Jesus von Nazareth seinen Platz zu seiner Erdenwirksamkeit gefunden hatte.

[ 18 ] Wenn man so hineinschaut in jene allerdings heute nicht mehr gültige Geisteswissenschaft — denn heute müssen wir auf eine andere Weise Geisteswissenschaft betreiben -, dann bekommt man eine ungeheure Achtung vor dem, was da gelehrt worden ist über das übersinnliche Weltenall, über den übersinnlichen Kosmos. Aber abhängig machte man die Erkenntnis dieses Weltenalls davon, daß immer die Weisheit übertragen werden sollte durch unmittelbare Schülerschaft gegenüber den älteren Eingeweihten; daß die Weisheit nur demjenigen übertragen werden sollte, den man zuerst in bezug auf seine Erkenntnisfähigkeiten wirklich bis zu der entsprechenden Stufe vorbereitet hatte, auf der er die Wesenheit des einen oder des anderen Gottes begreifen mußte.

[ 19 ] Man kann sagen: Überall, in Griechenland, in Ägypten, in Vorderasien wurde das innerhalb derjenigen Kreise, auf die es ankam mit Bezug auf die geistige Kultur, so angesehen, nicht aber innerhalb der römischen Welt. Diese römische Welt hatte ja allerdings auch noch Überreste jener alten Weisheit. Plotin selber lehrte lange Zeit in Italien, innerhalb der alten römischen Welt. Aber in die alte römische Welt war ein abstrakter Geist eingezogen, ein Geist, der nicht mehr im früheren Sinne den Wert der menschlichen Persönlichkeit verstehen konnte, den Wert des Wesenhaften überhaupt. Der Geist des Begrifflichen war eingezogen im Römertum, der Geist der Abstraktion; zwar noch nicht so wie in der späteren Zeit, aber weil er erst in seinen elementaren Formen war, wurde er, ich möchte sagen, um so energischer festgehalten.

[ 20 ] Und so sehen wir denn, als das 4. nachchristliche Jahrhundert beginnt, auf dem Boden von Italien eine Art von Schule, welche den Kampf gegen das alte Initiationsprinzip aufnimmt, welche überhaupt den Kampf aufnimmt gegen das Präparieren des einzelnen Menschen zur Initiation hin. Eine Schule sehen wir entstehen, welche alles das sammelt und sorgfältig registriert, was von den alten Initiationen überliefert ist. Diese Schule, die aus dem 3. in das 4. Jahrhundert noch herüberwächst, geht darauf aus, das römische Wesen selber zu verewigen, an die Stelle des unmittelbaren individuellen Strebens jedes einzelnen Menschen die historische Tradition zu setzen. Und in dieses römische Prinzip wächst nun das Christentum hinein. Verwischt werden sollte gerade von dieser Schule, die am Ausgangspunkte jenes Christentums steht, das erst etwa im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert beginnt, verwischt werden sollte namentlich alles, was man innerhalb der alten Initiation immerhin noch hat finden können über das Wohnen des Christus in der Persönlichkeit des Jesus.

[ 21 ] In dieser römischen Schule hatte man den Grundsatz: So etwas, wie es Ammonius Sakkas gelehrt hat, wie es Jamblichos gelehrt hat, darf nicht auf die Nachwelt kommen. — Geradeso wie man dazumal im breitesten Umfange darangegangen ist, die alten Tempel zu zerstören, die alten Altäre auszumerzen, zu vernichten, was vom alten Heidentum übriggeblieben war, so ging man in einer gewissen Weise geistig daran, alles, was die Auffindungsprinzipien der höheren Welt waren, auszulöschen. Und so setzte man, um ein Beispiel herauszugreifen, an die Stelle dessen, was man noch von Jamblichos und Ammonius Sakkas gewußt hatte: daß der einzelne Mensch sich hinaufentwickeln kann, um zu begreifen, wie der Christus im Leibe des Jesus Platz nimmt -, an die Stelle dessen setzte man das Dogma von der einen göttlichen Natur oder den zwei Naturen in der Persönlichkeit des Christus. Das Dogma sollte voll bewahrt werden, und die Einsicht, die Einsichtsmöglichkeit sollte verschüttet werden. Innerhalb des alten Rom ging die Umwandlung der alten Weisheitswege in die Dogmatik vor sich. Und man bemühte sich, alle Nachrichten, alles, was an das Alte erinnerte, möglichst zu zerstören, so daß von solchen Leuten wie Ammonius Sakkas, wie Jamblichos, nur die Namen geblieben sind. Von zahlreichen anderen, die als Weisheitslehrer in den südlichen Gegenden Europas waren, sind nicht einmal die Namen geblieben. So wie all die Altäre gestürzt worden sind, wie all die Tempel ausgerottet, bis auf den Boden verbrannt worden sind, so ist auch alte Weisheit ausgetilgt worden, so daß die Menschen heute nicht einmal ahnen, was in den ersten vier Jahrhunderten nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha noch im Süden Europas an Weisheit gelebt hat.

[ 22 ] Von dem aber, was da vorgegangen ist, erreichte die Kunde doch immerhin auch die anderen Menschen, die sich für solche Dinge interessierten, die da sahen, wie allerdings in rasendem Tempo das alte Römertum zugrunde ging, wie das Christentum sich ausbreitete. Aber nachdem man das, was, ich möchte sagen, an glorreichem Empfang dem Mysterium von Golgatha bereitet worden war, ausgelöscht hatte, konnte man ja die Vereinigung des Christus mit dem Jesus nur noch in einem Dogma sehen, das dann durch die Konzilien mehr oder weniger abstrakt aus romanisch-römischem Geist heraus festgelegt worden ist. Ausgelöscht wurde die lebendige Weisheit, und die Abstraktion, die dann als Offenbarungsinhalt weiterwirkte, trat an ihre Stelle.

[ 23 ] Die Geschichte von diesen Dingen ist ja wie ausgelöscht, aber dazumal, in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten, gab es zahlreiche Menschen, die sagten: Ja, es leben solche Eingeweihte, wie Jamblichos einer war. Das sind diejenigen, die von dem wirklichen Christentum erzählten. Für die ist der Christus der «Christus». Aber was haben die Römer immer mehr und mehr gemacht? Die Römer haben aus dem Christentum gemacht, was man nur «Die Galiläer» nennen kann. Das war eine Zeitlang, als das 3., 4. Jahrhundert begann, ein Ausdruck, der gebraucht wurde, um ein großes Mißverständnis zuzudecken. Als das Christentum immer weniger und weniger verstanden wurde, sprach man immer mehr und mehr von den Galiläern; immer weniger wußte man von dem Christus, immer mehr gab man auf die menschliche Persönlichkeit des «Galiläers».

[ 24 ] Aus diesem geistigen Milieu heraus ist dann Julianas, der sogenannte Apostat, erwachsen, der noch vieles von Schülern des Jamblichos aufgenommen hat, der noch etwas davon wußte, daß ein geistiges Weltenall da ist, das herunterreicht bis in die einzelnen Naturdinge hinein. Von den Schülern des Jamblichos hat Julianus der Apostat noch gehört, wie bis in das einzelne 'Tier, in die einzelne Pflanze hinein die Kräfte wirken von den 360 himmlischen Mächten, den 72 Zwischenmächten, den planetarischen Mächten, den 42 irdischen Mächten. Man verstand in der damaligen Zeit noch so etwas, wie es sich wunderbar ausdrückt in einer Legende, die in bezug auf die Persönlichkeit des Plotin erzählt wird und die eine tiefe Bedeutung hat. Diese Legende lautet: Es gab schon viele, welche nicht mehr glauben wollten, daß jemand mit dem göttlichen Geist inspiriert sein könnte, und die sagten, daß jemand, der selber behauptet, er wisse etwas von der göttlich-geistigen Welt, von einem Dämon besessen sei. Deshalb wurde Plotin vor den ägyptischen Isistempel geschleppt, wo sich entscheiden sollte, welcher Dämon den Plotin von sich besessen gemacht hätte. Und als die ägyptischen Priester kamen, die noch eine Kenntnis von diesen Dingen hatten, und, vor dem Isisaltar, mit all den Kultushandlungen, die dazumal möglich waren, den Plotin prüften, siehe, da kam statt eines Dämons die Gottheit selbst zum Vorschein! — Es gab also in jenen Zeiten immerhin noch die Möglichkeit, wenigstens zuzugeben, daß man prüfen könne, ob irgend jemand in sich den guten Gott oder einen Dämon trüge.

[ 25 ] Von solchen Dingen hörte Julian der Apostat noch. Aber auf der anderen Seite klang in seinen Ohren auch noch so etwas wie jene Schrift, die viel in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten im Römerreich herumging und die man eine Predigt des Apostels Petrus nannte, die aber eine Fälschung war. In dieser Schrift wurde gesagt: Seht hin auf die gottlosen Hellenen, die sehen in jedem einzelnen Naturwesen ein Göttlich-Geistiges. Das ist gottlos, das dürft ihr nicht! Ihr dürft in der Natur, in dem Tier, in der Pflanze nicht irgend etwas Göttlich-Geistiges sehen, ihr dürft euch nicht erniedrigen zu dem Glauben, daß im Sonnengang oder im Mondengange irgend etwas Göttliches enthalten sei. — So klang es an Julianus den Apostaten heran, von der einen und von der anderen Seite her. Und er faßte eine tiefe Liebe zu dem Hellenentum. Er wurde zu der tragischen Persönlichkeit, welche in dem Sinne des Jamblichos über das Christentum reden wollte.

[ 26 ] Es ist gar nicht auszudenken, was etwa in Europa geschehen wäre, wenn nicht das Römertum, sondern das Christentum Julians des Apostaten gesiegt hätte, wenn gesiegt hätte sein Wille, die Initiationsschulen wiederum aufzubauen, so daß die Menschen selber hätten Einsicht nehmen können, wie der Christus in dem Jesus gewohnt hat und wie der Christus zu den anderen Volksgöttern stand. Julian Apostata wollte nicht die heidnischen Tempel zerstören. Er wollte sogar den Tempel zu Jerusalem, den Judentempel wieder herstellen. Er wollte die heidnischen Tempel wieder herstellen, und er nahm sich auch der Christen an. Nur eben Wahrheit wollte er haben. Er wurde vor allen Dingen durch jene Schule des alten Rom gestört, von der ich gesprochen habe, die das alte Initiationsprinzip auslöschen wollte und auch in Wirklichkeit ausgelöscht hat und die bloß die Traditionen, die registrierten alten Initiationsweisheiten an deren Stelle setzen wollte.

[ 27 ] Und man wußte es ja einzurichten, daß Julian im richtigen Momente von einer persischen Lanze getroffen wurde. Dazumal fiel das Wort, das seither niemals, auch nicht von Ibsen verstanden worden ist, das aber aus der damaligen Tradition heraus verstanden werden kann: Leider nicht der Christus, der Galiläer hat gesiegt! — Denn in diesem Todes-, in diesem Sterbemomente stand vor Julian Apostatas prophetischem Blick die Aussicht, daß nun immer mehr und mehr die Anschauung von dem göttlichen Christus schwinden werde, und der «Galiläer», der nur aus dem Galiläerstamm heraus stammende Mensch, allmählich wie ein Gott verehrt werden wird. Die ganze Entwickelung, die dann immer weiter heraufkam, bis in der neueren Zeit, im 19. Jahrhundert, die Theologie den Christus in dem Jesus vollständig verloren hatte, sie sah, mit einem ungeheuren Seherblick dazumal, in seinem dreißigsten Lebensjahre, Julian der Apostat voraus. Apostat war er in bezug auf das, was eigentlich erst kam. Der Apostat war eigentlich ein Apostel in bezug auf das, was ein Erfassen des Mysteriums von Golgatha im Geiste war und wieder werden muß.

[ 28 ] Neuere geologische Schichten bedecken immer die alten, und man muß erst durch die neueren Schichten hindurch, wenn man zu den alten hinunterkommen will. Man möchte vielleicht nicht glauben, wie dick die Schichten sind, die historisch abgelagert sind im Menschenwerden. Denn, was sich da vom 4. Jahrhundert ab unter dem Einfluß des Romanismus als Schichten gelegt hat über die ersten Auffassungen des Mysteriums von Golgatha, das ist sehr dick. Aber wir müssen wiederum die Möglichkeit finden, durch ursprüngliche Geisteserkenntnisse diese Schichten zu durchdringen, um auch das Altehrwürdige, das als Geistiges ebenso hinweggefegt worden ist wie die alten heidnischen Altäre, wiederzufinden.

[ 29 ] Die ägyptischen Priester haben noch konstatiert, daß Plotin nicht einen Teufel, einen Dämon, sondern einen Gott in sich trug. Im europäischen Westen konstatierte man aber, daß er jedenfalls einen Dämon in sich hatte. Lesen Sie die Dinge nach bis herauf zu der Rede von Brentano «Was für ein Philosoph manchmal Epoche macht», dann werden Sie finden: Die ägyptischen Tempelpriester konstatierten, daß in dem Plotin, in dem Philosophen des 3. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts, nicht ein Dämon, sondern ein Gott lebte; Brentano konstatierte, daß nicht ein Gott, sondern ein Dämon in ihm lebte.

[ 30 ] Und das ist es, was nun auch geschah im 19. Jahrhundert: daß die Götter für Dämonen und die Dämonen für Götter angesehen wurden, daß man nicht mehr unterscheiden konnte im Weltenall zwischen Göttern und Dämonen. Das aber lebt dann in dem Chaos unserer Zivilisation weiter.

[ 31 ] Ja, es macht schon nachdenklich, wenn man diese Dinge sachgemäß ins Auge faßt. Ich wollte Ihnen nur ein Kapitel Geschichte heute vortragen, ganz objektiv, denn selbstverständlich mußte alles sein, was geschichtlich geworden ist. Aber auch das muß wiederum sein, daß, wenn es notwendig war, daß die Menschen ein gewisses Zeitalter hindurch über gewisse Dinge unaufgeklärt blieben, sie dann nachträglich wiederum aufgeklärt werden und diese Aufklärung auch wirklich entgegennehmen.

Eleventh lecture

[ 1 ] During the last lecture, I had to repeatedly draw attention to how, during the heyday of the Middle Ages within European civilization, two currents of thought ran through the best minds, those two currents of thought which I characterized more precisely yesterday as revelatory knowledge and rational knowledge within scholasticism. Now, we had to emphasize that knowledge of revelation, in the sense in which it appears within scholasticism, is by no means something mystical or abstractly indefinite, but rather that it is a content of knowledge that appears in sharply contoured, sharply formed concepts. It is simply that these concepts are not acknowledged as being immediately accessible to human cognition, but rather it is pointed out that they must be taken from the tradition of the churches by each individual who is to come into possession of them, since it is precisely in their traditions and in their continuous existence that the churches have the right, as it were, to preserve such cognitive content.

[ 2 ] The second piece of knowledge was made available to human research and human endeavour; but those who were truly within the true scholastic tradition had to acknowledge that this rational knowledge could not be used to gain any knowledge of the supersensible world.

[ 3 ] Thus, in the spiritual flowering of the Middle Ages, it was acknowledged that certain knowledge that was no longer accessible to people at that time had to be preserved historically. But I have already indicated that this was not always the case. If we go further back, through the Middle Ages to the first Christian centuries, we find that this special character of revelatory knowledge is not emphasized as sharply as it was in the later Middle Ages. And if you had presented something like this to a Greek, say, from the Athenian school of philosophy, such as a separation of knowledge into mere rational knowledge and knowledge given only through revelation—revelation taken in the sense in which it was taken in the Middle Ages—the Greek philosopher would not have understood it at all. He would not have been able to comprehend that once a piece of knowledge about the supernatural had been communicated to humans by an otherworldly power, it would then remain and could not be communicated again. The Greeks understood that the higher spiritual content could not be attained through the usual methods of knowledge; but he understood that through spiritual training, through the path of initiation, one can ascend from the cognitive abilities that one has as a human being to higher cognitive abilities. Then one enters the world in which one is able to see what is truth and knowledge for the supersensible.

[ 4 ] And it is precisely in relation to this matter that a turning point occurred in the entire Western civilization between what existed in the centuries when Greek philosophy was still flourishing in Plato and Aristotle, and what then arose at the end of the 4th century AD. I have already emphasized one side of this matter on several occasions. I have emphasized that the event of Golgotha took place at a time when much of the ancient wisdom of initiation, the ancient knowledge of initiation, was still available. And indeed, enough people applied the ancient wisdom of initiation to understand the event of Golgotha through their initiation, using the means of supersensible knowledge. Initiates endeavored to use all the initiation knowledge they could gather to understand how a being such as Christ, who was not united with earthly evolution before the time of the Golgotha mystery, could connect with an earthly body and now remain united with human evolution. What kind of being this was, how this being behaved before it descended into the earthly realm—these were all questions that required the highest initiatory abilities to answer, even at the time of the mystery of Golgotha.

[ 5 ] Now, however, we see that the ancient wisdom of initiation, which was certainly present in the Near East, in North Africa, and also within Hellenic culture, and which spread to Italy and even further into Europe, has been understood less and less since the fifth century AD. People then spoke of individual names in such a way that the bearers of these names were portrayed within Western Christian civilization as rather contemptible personalities, or at least as personalities with whom a true Christian should not concern himself. Efforts were also made to erase as far as possible all traces of earlier knowledge of what these personalities actually represented.

[ 6 ] It is remarkable that a personality such as Franz Brentano, coming from his medieval tradition, still inherited for his own soul the hatred of everything that lived at that time in personalities such as PJozin, about whom very little was known, but who was regarded as a philosopher with whom a true Christian confessor should not concern himself. Brentano shared this hatred of Plotinus. He inherited it. He wrote a treatise entitled “What kind of philosopher sometimes makes an epoch,” referring to Plotinus, the philosopher of the third century AD, who was part of the intellectual currents that actually dried up completely in the fourth century and which no one wanted to remember in the later development of Christianity.

[ 7 ] What is said in the usual philosophies of history about the very outstanding minds of that time, the first Christian centuries, is mostly not only the bare minimum, but it is such that not the slightest coherent idea about these minds can be gained from it. It is natural that even today it is still very difficult to form a clear picture of the first three or four centuries of Christianity. For example, how the ideas of Plato and Aristotle continued to have an effect, even though they were already alienated in a certain sense from the deeper wisdom of the mysteries, which personalities such as those I have in mind still possessed in the first three or four Christian centuries. Today, there is hardly any proper knowledge of Plato in the usual histories of philosophy. If you are interested in this, take a look at the chapter on Plato in Paul Deussen's History of Greek Philosophy, where Deussen discusses how Plato actually thought about the idea of the good in relation to other ideas. There you will find sentences such as this: Plato did not accept a personal God, otherwise the ideas he accepted would not have been independent; Plato could not recognize an essential God because ideas are independent. However, Deussen says, Plato again places the idea of the good above the other ideas. But that does not mean that the idea of the good stands above the other ideas as something essentially independent; for what the idea of the good expresses is only a certain family resemblance that is present in all ideas.

[ 8 ] Please sit down properly in your chairs and take a closer look at Deussen's logic, the logic of an outstanding contemporary philosopher. Plato has ideas. They are independent. Now Plato also has the idea of the good. But this cannot be just anything that directs the other ideas; rather, the ideas have a family resemblance to each other. The idea of the good merely expresses this family resemblance. Yes, but where do family resemblances come from? If there is a family resemblance somewhere, it comes from descent from at least one superior, if one wants to use that expression. The idea of the good points to a family resemblance; so you would have to get to the progenitor first!

[ 9 ] Yes, that's in excellent contemporary histories of philosophy! People who write such things become authorities in the present. People learn this and don't realize that it's pure nonsense. Of course, you can't expect someone who talks such nonsense about Greek philosophy to have much to say about Indian wisdom. But nevertheless, if you look for something authoritative on Indian wisdom today, you will be referred to Paul Deussen. Things are bad indeed.

[ 10 ] I just wanted to say that at present there is not much point in trying to understand Platonic philosophy itself. Contemporary intellectualism is simply incapable of doing so. Therefore, something that at least still belongs to the traditions cannot be understood. That is that Plotinus, the Neoplatonic philosopher—as he is always called—was a student of Ammonius Saccas, who lived at the beginning of the 3rd century AD, but wrote nothing, only teaching individual students. The most outstanding minds of that time wrote nothing at all because they believed that the content of wisdom must exist as something living, that it could not be transferred from one person to another through writing, but only from person to person in direct personal communication. Now there is another story about Ammonius Sakkas, the meaning of which is again not clear to people. It is said that he tried to achieve unity between the terrible disputes of the followers of Aristotle and the followers of Plato by showing how Plato and Aristotle were actually in complete harmony with each other.

[ 11 ] I would like to characterize in a few strokes how this Sakkas might have spoken about Plato and Aristotle. He characterized them as follows: Plato still belonged to an age in which many people found their immediate path to the spiritual world, in other words, in which people were still well acquainted with the principle of initiation. But in earlier times, Ammonius Sakkas may have said, logical-abstract thinking was not yet developed. Only the first traces of this are now visible — I mean “now” at the beginning of the 3rd century AD. Thoughts formed by human beings did not actually exist even in Plato's time. But while older initiates gave everything they had to give to people only in images, in imaginations, Plato was one of the first to transform imaginations into abstract concepts. If one imagines the powerful image content (red) to which Plato wanted people to look up, it was certainly the case that in earlier times this image content was expressed merely in imaginations (orange), but for Plato already in concepts (white). But these concepts flowed down, as it were, from the divine-spiritual content (arrows). Plato said: The lowest revelation, in a sense the most diluted revelation of the divine-spiritual content, are the ideas. Aristotle no longer had such an intense possibility of raising himself up to this spiritual content. Therefore, he had, in a sense, only what was below the image content; he had only the idea content. But he could still understand this as something revealed. There is no difference between Plato and Aristotle, said Sakkas, for example, other than that Plato looked higher up into the spiritual world, and Aristotle looked less high up into the spiritual world.

[ 12 ] With this, Ammonius Sakkas believed he had swept away the disputes that existed among the followers of Aristotle and Plato. And even if the content of wisdom already approached intellectualism under Plato and Aristotle, there were still possibilities in those ancient times for one person or another to actually ascend very far into the realm of spiritual vision through personal experience. And so one must imagine that such people as Ammonius Sakkas and his disciple Plotinus were indeed still full of inner, immediate spiritual experiences and, above all, had such spiritual experiences that their view of the spiritual world had a completely concrete content. Of course, one could not have spoken to such people about an external nature as one does today. Such people spoke of a spiritual world in their schools, and nature below, which today is considered by many to be the be-all and end-all, was only the lowest figurative expression of what they were conscious of as the spiritual world. One can get an idea of how such people spoke by looking at one of Sakkas' followers, who still had deep insights and carried them over into the 4th century: Jamblichus.

[ 13 ] Let us imagine the worldview of Jamblichus. He spoke to his disciples in the following manner. He said: If one wants to understand the world, one must not look at space, for in space there is only the outer expression of the spiritual world. Nor should one look at time, for time merely plays out the illusion of what is the real, true content of the world. One must look up to those powers in the spiritual world that shape time and the connection of time with space. Look out into the whole universe. Every year the cycle repeats itself, visibly expressed in the sun. But this sun circles through the zodiac, through the 12 constellations. One should not just stare at this. For 360 heavenly powers are working and weaving in it, and it is they who bring about everything that emanates from the sun's activity during the course of a year for the whole world accessible to human beings, and they repeat the cycle every year. If they ruled alone, the year would have 360 days, as Jamblichus told his students. But that leaves five days. These five days are directed by 72 sub-celestial powers, the planetary spirits. I draw this pentagon in the circle, because 72 is to 360 as 1 is to 5. The five remaining world days of the year, in which the 360 heavenly powers would leave a void, so to speak, are directed by the 72 sub-celestial powers. Now you know that the year has not only 365 days, but also a few hours more; according to Jamblichus, there are 42 earthly powers for these hours.

[ 14 ] Jamblichus went on to say to his disciples: The 360 heavenly powers are connected with everything that is the main organization of the human body. The 72 sub-heavenly powers are connected with everything that is the organization of the chest, respiration, and heart, and the 42 earthly powers are connected with everything that is the purely earthly organization of digestion, metabolism, and so on in humans.

[ 15 ] Thus, man was placed within a spiritual system, a spiritual world system. Today, we begin our study of physiology by learning how much carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, calcium, and so on, man absorbs. We relate human beings to what is lifeless nature. In his schools, Jamblichus would have presented human beings as standing in relation to the 42 earthly powers, the 72 intermediate or planetary powers, and the 360 heavenly powers. Just as humans are depicted today as something composed of the substances of the earth, so humans were depicted in those days as something flowing down from the forces, from the agencies of the spiritual universe. One can only say that it was an immense, a high wisdom that was represented in these schools at that time. One can understand that Plotinus, who only became a listener of Ammonius Saccas at the age of twenty-eight, felt as if he were in another world because he was able to absorb something of this wisdom. And this wisdom was still cultivated in many places in the first four centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha. With this wisdom, people also tried to understand how Christ had come down to Jesus of Nazareth. They tried to understand how Christ placed himself in this whole powerful world of spiritual hierarchies, in this spiritual world structure.

[ 16 ] And now I want to discuss another chapter of Jamblichus' wisdom, which he taught in his schools. He said: There are 360 heavenly powers, 72 planetary powers, and 42 earthly powers. So there are a total of 474 divine beings of various ranks. Now, Jamblichus said to his disciples, you can look in the far east, where you will see that there are peoples who will tell you the names of their gods. Then go to the Egyptians, who will also tell you the names of their gods, and to other peoples, who will also tell you the names of their gods. Then go to the Phoenicians, then to the Hellenes, and again you will find names of gods. And if you go over to the Romans, you will find names of gods again. If you take the 474 names of gods, all these different gods of the different peoples are contained therein: Zeus, Apollo, also Baal, Amon, the Egyptian god, all gods belong to these 474. The fact that peoples have different gods is only because one people took 12 or 17 from the 474 gods, another 20 or 25, another people 3, 4, and so on. But if one understands these different deities of the different peoples correctly, then one arrives at 473. And the highest, the most distinguished, the one who came down to earth at a certain time, is Christ.

[ 17 ] It was precisely in this wisdom that there was a deep tendency to establish peace among the most diverse religions, but not out of a vague feeling, but by wanting to recognize how, for those who truly knew the 474 gods from the structure of the world, the various deities of the different peoples were arranged in a great system, and one wanted to understand the entire pantheon of all the peoples of ancient times in such a way that it all culminated in Christianity. This structure was to be crowned by the understanding of how Christ, in Jesus of Nazareth, had found his place for his earthly mission.

[ 18 ] If one looks into this spiritual science, which is no longer valid today—for today we must pursue spiritual science in a different way—one gains tremendous respect for what was taught about the supersensible universe, about the supersensible cosmos. But knowledge of this universe was made dependent on the wisdom always being transmitted through direct discipleship to the older initiates; on the wisdom only being transmitted to those who had first been truly prepared in terms of their cognitive abilities to the level at which they had to comprehend the essence of one or the other God.

[ 19 ] One can say that everywhere, in Greece, in Egypt, in the Near East, this was regarded as true within those circles that were important in terms of spiritual culture, but not within the Roman world. The Roman world did, of course, still have remnants of that ancient wisdom. Plotinus himself taught for a long time in Italy, within the old Roman world. But an abstract spirit had entered the old Roman world, a spirit that could no longer understand the value of the human personality in the former sense, the value of the essential in general. The spirit of conceptualization had entered Roman culture, the spirit of abstraction; not yet as it would be in later times, but because it was still in its elementary forms, it was, I would say, held on to all the more energetically.

[ 20 ] And so we see, at the beginning of the fourth century after Christ, a kind of school emerging in Italy which takes up the fight against the old principle of initiation, which takes up the fight against the preparation of the individual human being for initiation. We see a school emerging that collects and carefully records everything that has been handed down from the ancient initiations. This school, which grew out of the third century into the fourth, sought to perpetuate the Roman essence itself, to replace the immediate individual striving of each individual human being with historical tradition. And it was into this Roman principle that Christianity now grew. It was precisely this school, which stands at the beginning of Christianity, which only began in the 4th century AD, that sought to obscure everything that could still be found within the old initiation concerning the dwelling of Christ in the personality of Jesus.

[ 21 ] In this Roman school, the principle was: anything that Ammonius Sakkas taught, anything that Jamblichos taught, must not be passed on to posterity. Just as in those days people went about destroying the old temples, eradicating the old altars, and destroying what remained of the old paganism, so in a certain spiritual sense they set about eradicating everything that was the principle of discovery of the higher world. And so, to pick out one example, in place of what was still known from Iamblichus and Ammonius Saccas—that the individual human being can develop upward to understand how Christ takes his place in the body of Jesus—in place of this, the dogma of the one divine nature or the two natures in the personality of Christ was put. The dogma was to be preserved in its entirety, and insight, the possibility of insight, was to be buried. Within ancient Rome, the transformation of the old paths of wisdom into dogma took place. And every effort was made to destroy all information, everything that reminded people of the old ways, so that only the names of people like Ammonius Sakkas and Iamblichus remained. Of numerous others who were teachers of wisdom in the southern regions of Europe, not even their names have survived. Just as all the altars were torn down, all the temples destroyed and burned to the ground, so too was ancient wisdom wiped out, so that people today have no idea what wisdom was still alive in southern Europe in the first four centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha.