Man and Cosmos

GA 220

7 January 1923, Dornach

Translator Unknown

Within this course of lectures I intend to speak of things which are connected with the preceding lectures, but which bring results of spiritual science drawn from a deeper source and show how the human being is placed in the universe. We speak of man in such a way that we envisage, to begin with, his physical organization and his etheric or vital body revealed to spiritual investigation; and then we speak of the astral body and of the Ego organization. But we do not yet grasp man's structure if we simply enumerate these things in sequence, for each of these members has a different place in the universe. We are able to grasp man's position in the cosmos only if we understand how these different members are placed in the universe.

When we study the human being, as he stands before us, we find that these four members of human nature interpenetrate in a way which cannot at first be distinguished; they are united in an alternating activity, and in order to understand them we must first study them separately, as it were, and consider each one in its special relation to the universe. We can do this in the following way, by setting out, not from a more general aspect, but from a definite standpoint.

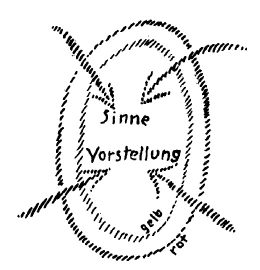

Bear I mind, to begin with, the more peripheric aspect of man, the external boundary, what is outside him. From other anthroposophical studies we know that we discover certain senses only when we penetrate, as it were, below the surface of the human form, into man's inner life. But essentially speaking, also the senses which transmit us a knowledge of our own inner being, have to be sought in regard to their starting point, and to begin with in a very unconscious way, on the inner side of the surface of man's being. We may therefore say: Everything in man existing in the form of senses should be looked for on the surface. It suffices to bear in mind one of the more prominent senses; for example, the eye or the ear—these show that the human being must obtain certain impressions from outside. How matters really stand in regard to these senses should, of course, be studied more deeply, by a more profound research. This has already been done here for some of the human senses. But the way in which these things appear in ordinary life induces us to say: A sense organ—for example, the eye or the ear—perceives things through impressions coming from outside.

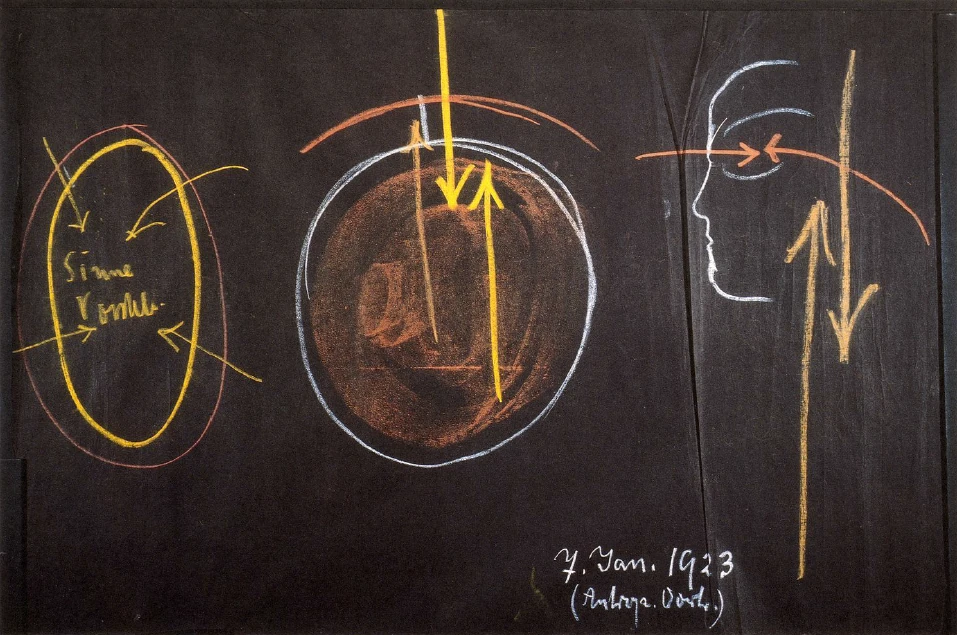

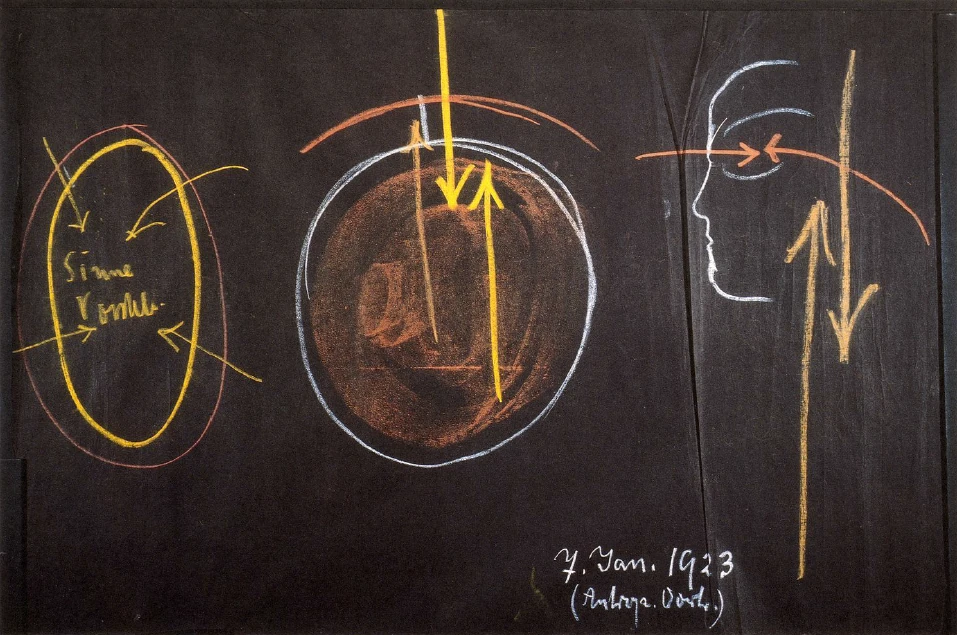

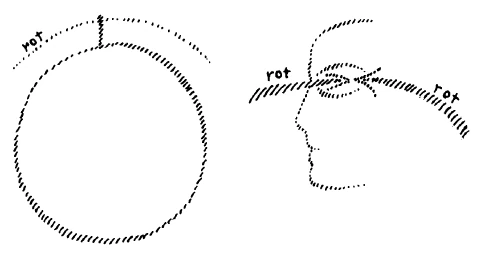

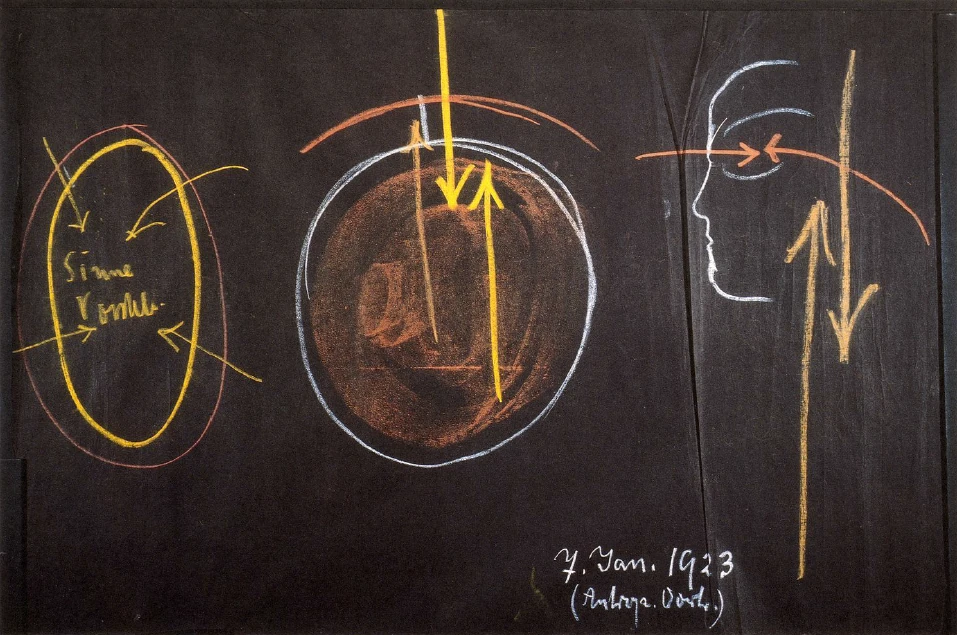

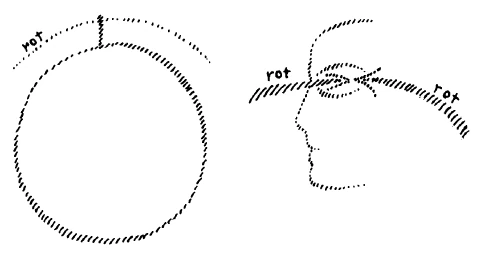

Man's position on earth easily enables us to see that the chief direction which determines the influences enabling him to have sensory perceptions can approximately be described as “horizontal.” A more accurate study would also show us that this statement is absolutely correct; for when perceptions apparently come from another direction, this is an illusion. Every direction relating to perception must in the end follow the horizontal. And the horizontal is the line which runs parallel to the surface of the earth. If I now draw this schematically, I would therefore have to say: If this is the surface of the earth, with the perceiving human being upon it, the chief direction of his perceptions is the one which runs parallel to the earth. All our perceptions follow this direction. And when we study the human being, it will not be difficult to say that the perceptions come from outside; they reach, as it were, man's inner life from outside. What meets them from inside? From inside we bring towards them our thinking, the power of forming representations or thoughts.

If you consider this process, you cannot help saying: When I perceive through the eye, I obtain an impression from outside, and my thinking power comes from inside. When I look at the table, its impression comes from outside. I can retain a picture of the table in my memory through the representing or thinking power which comes from within. We may therefore say: If we imagine a human being schematically, the direction of his perceptions goes from the outside to the inside, whereas the direction of his thinking goes from the inside to the outside.

What we thus envisage, is connected with the perceptions of the earthly human being in ordinary life, of the earthly human being appearing to us externally in the present epoch of the earth's development. The things mentioned above are facts evident to the ordinary human consciousness. But if you study the anthroposophical literature, you will find that there are other possibilities of consciousness differing from those which exist for the earthly human being in ordinary life.

I would now ask you to form, even approximately and vaguely, a picture of what the earthly human being perceives. You look upon the colours which exist on earth, you hear sounds, you experience sensations of heat, and so forth. You obtain contours of the things you perceive, so that you perceive their shape, and so forth.

But all the things in our environment, with which we have thus united ourselves, only constitute facts pertaining to our ordinary consciousness. There are, however, other possibilities of consciousness, which remain more unconscious in the earthly human being and are pushed into the depths of his soul life; yet they are just as important, and frequently far more important in human life than the facts of consciousness which exhaust themselves in what I have described so far.

For the human constitution which man has here on earth, the things below the surface of the earth are just as important as those which exist in the earth's circumference. The circumference of the earth, what exists around the earth, may be perceived by the ordinary senses and grasped by the representing capacity which meets sense perception. This fills the consciousness of the ordinary human being living on the earth.

But let us consider the inside of the earth. Simple reflection will show you that the inside of the earth is not accessible to ordinary consciousness. We may, to be sure, make excavations reaching a certain depth and in these holes—for example in mines—observe things in the same way in which we observe them on the earth's surface. But this would be the same as observing a human corpse. When we study a corpse, we study something which no longer constitutes the whole human being, but only a residue of man as a whole. Indeed, those who are able to consider such things in the right way must even say: We are then looking upon something which is the very opposite of man. The reality of earthly man is the living human being walking around, and to him belong the bones, muscles, etc. which exist in him. The bone structure, the muscular structure, the nerve structure, the heart, lungs, etc. correspond to the living human being and are as such true and real. But when I look upon the corpse, this no longer corresponds to the living human being. The form which lies before me as corpse, no longer requires the existence of lungs, of a heart, or of a muscular system. Consequently these decay. For a while they maintain the form given to them, but a corpse is really an untruth, for it cannot exist in the form in which it lies before us; it must dissolve. It is not a reality. Similarly the things I perceive when I dig a hole into the earth are not realities.

The closed earth influences the human being standing upon it, differently from the things which exist in such a way that when the human being stands upon the earth, he beholds them through his senses, as the earth's environment.

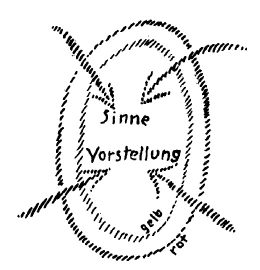

If, to begin with, you consider this from the soul aspect, you may say: The earth's environment is able to influence man's senses and it may be grasped by the thinking or representing capacity pertaining to ordinary human consciousness. Also what is inside the earth exercises an influence upon man, but it does not follow the horizontal direction; it rises from below. In our ordinary state of consciousness, we do not perceive these influences rising from below in the same way in which we perceive the earth's environment through the ordinary senses. If we could perceive what rises up from the earth in the same way in which we perceive what exists in the earth's environment, we would need a kind of eye or organ of touch able to feel into the earth, without our having to dig a hole into it, so that we could reach or see through (durchgreifen) the earth in the same way in which we see through air when we behold something. When we look through air, we do not dig a hole into it; if we first had to dig a hole into air, in order to look at it, we would see our environment in the same way in which we would see the earth in a coal mine. Hence, if it were not necessary to dig a hole into the earth in order to see its inside, we would have to have a sense organ able to see without the need of digging holes into the earth, an organ for which the earth, such as it is, would become transparent to sight or touch. In a certain way this is the case, but in ordinary life these perceptions do not reach human consciousness. For what the human being would then perceive are the earth's different kinds of metals.

Consider how many metals are contained in the earth. Even as you have perceptions in your air-environment—if I may use this expression—even as you see animals, plants, minerals, artistic objects of every kind, so perceptions of the metals rise up to you from the earth's inside. But if perceptions of the metals could really reach your consciousness, they would not be ordinary perceptions, but imaginations. And these imaginations continually reach man, by rising up from below. Even as the visual impressions come, as it were, from the horizontal direction, so the radiations of metals continually reach us from below; yet they are not visual perceptions of the minerals, but something pertaining to the inner nature of minerals, which works its way up through us and takes on the form of imaginations or pictures. But the human being does not perceive these pictures; they are weakened. They are suppressed, as it were, because man's earthly consciousness is not able to perceive imaginations. They are weakened down to feelings.

If, for example, I imagine all the gold existing in some way in the caverns of the earth, and so forth, my heart really perceives an image which corresponds to the gold in the earth. But this picture is an imagination, and for this reason ordinary human consciousness cannot perceive it, for it is dulled down to a life feeling, an inner vital feeling, which cannot even be interpreted, less still perceived, in its corresponding image. The same applies to the other organs, for the kidneys perceive in a definite image all the tin which exists in the earth, and so forth.

All these impressions are subconscious and they do not appear in the general feelings that live in the human being. You may therefore say: The perceptions coming from the earth's environment follow a horizontal direction and are met from within by the thinking or representing power; from below come the perceptions of metals—above all, of metals—and they are met by feeling, in the same way in which ordinary perceptions are met by the thinking capacity. This process, however, remains chaotic and unreal to the human beings of the present time. From these impressions they only derive a general life-feeling.

If the human being on earth had the gift of imagination, he would know that his nature is also connected with the metals in the earth. In reality, every human organ is a sense organ, and although we use it for another purpose, or apparently do so, it is nevertheless a sense organ. During our earthly life, we simply use our organs for other purposes. For we really perceive something with each organ. The human being is in every way a great sense organ, and as such, he has differentiated, specified sense organs in the single organs of his body.

You therefore see that from below, the human being obtains perceptions of metals and that he has a life of feeling corresponding to these perceptions. Our feelings exist in contrast to everything coming to us from the earth's metals, even as our thinking or representing power exists in contrast to everything which penetrates into our sense perceptions from the earth's environment.

But in the same way in which the influences of the metals reach us from below, so we are influenced from above by the movements and forms of the celestial bodies in the world's spaces. We have sense perceptions in our environment, and similarly we have a consciousness which would manifest itself as inspired consciousness, as inspirations coming from every planetary movement and from every constellation of fixed stars. Even as our thinking capacity streams towards our ordinary sense perceptions, so we send out to the movements of the celestial bodies a force which is opposed to the impressions derived from the stars, and this force is our will. What lies in our will power, would be perceived as inspiration, if we were able to use the inspired state of consciousness.

You therefore see that by studying man in this way, we must say to ourselves: In his earthly consciousness we find, to begin with, the condition in which he is most widely awake: his life of sensory perceptions and of thoughts. During our ordinary, earthly state of consciousness, we are completely awake only in this life of sensory perceptions and thoughts. Our feeling life, on the other hand, only exists in a dreaming state. There, we only have the intensity or clearness of dreams, but dreams are pictures, whereas our feeling life is the general soul constitution determined by life; that is to say, feeling. But at the foundation of feeling lie the metal influences coming from the earth. And the consciousness based on the will lies still deeper. I have frequently explained this. Man does not really know the will that lives in him. I have often explained this by saying: The human being has the thought of stretching out his arm, or of touching something with his hand. He can have this thought in his waking consciousness and may then look upon the process of touching something. But everything that really lies in between, the will which shoots into his muscles, etc., all this remains concealed to our ordinary consciousness, as deeply hidden as the experiences of a deep slumber without dreams. We dream in our feelings and we sleep in our will. But the will which sleeps in our ordinary consciousness responds to the impressions coming from the stars, in the same way in which our thoughts respond to the sense impressions of ordinary consciousness. And what we dream in our feelings is the counter-activity which meets the influences coming from the metals of the earth.

In our present waking life on earth, we perceive the objects around us. Our thinking capacity counteracts. For this we need our physical and etheric body. Without the physical and etheric body we could not develop the forces which work in a horizontal direction—the perceptive and thinking forces. If we imagine this schematically we might say: As far as our daytime consciousness is concerned, the physical and etheric bodies become filled with sense impressions and with our thinking activity. When the human being is asleep, his astral body and his Ego organization are outside. They receive the impressions which come from below and from above. The Ego and the astral body really sleep in the metal streams rising up from the earth, if I may use this expression, and in the streams descending from the planetary movements and the constellations of fixed stars.

What thus arises in the earth's environment exercises no influence in a horizontal direction, but exists in form of forces which descend from above, and in the night we live in them.

If you could attain the power of imagination by setting out from your ordinary consciousness, so that the imaginative consciousness would really exist, you would have to achieve this in accordance with the demands of the present epoch of human development; namely, in such a way that every human organ is seized by the imaginative consciousness. For example, it would have to seize not only the heart, but every other organ. I have told you that the heart perceives the gold which exists in the earth. But the heart alone could never perceive the gold. This process takes place as follows: As long as the Ego and astral body are connected with the physical and etheric bodies, as is normally the case, the human being cannot be conscious of such a perception. Only when the Ego and the astral body become to a certain extent independent, as is the case in imagination, so that they do not have to rely on the physical and etheric bodies, we may say: The astral body and the Ego organization acquire, near the heart, the faculty of knowing something about these radiations coming from the metals in the earth. We may say: The center in the astral body for the influences which come from the gold radiations, lies in the region of the heart. For this reason we may say: The heart perceives—because the real perceptive instrument in the astral body pertaining to this part, to the heart—not the physical organ, but the astral body, perceives.

If we acquire the imaginative consciousness, the whole astral body and also the whole Ego organization must enable the parts corresponding to every human organ to perceive. That is to say, the human being is then able to perceive the whole metal life of the earth—differentiated, of course. But details in it can only be perceived after a special training, when he has passed through a special occult study, enabling him to know the metals of the earth. In the present time, such a knowledge would not be an ordinary one. And today it should not be applied to life in a utilitarian way. It is a cosmic law that when the knowledge of the earth's metals is used for utilitarian purposes in life, this would immediately entail the loss of the imaginative knowledge.

Last part—It may, however, occur that owing to pathological conditions, the intimate connection which should exist between the astral body and the organs is interrupted somewhere in man's being, or even completely, so that the human being sleeps, as it were, quite faintly, during his waking condition. When he is really asleep, his physical body and his etheric body on the one hand, and his astral body and his Ego on the other, are separated; but there also exists a sleep so faint that a person may walk about in an almost imperceptible state of stupor—a condition which may perhaps appear highly interesting to some, because such people have a peculiarly “mystical” appearance; they have such mystical eyes and so forth. This may be due to the fact that a very faint sleeping state exists even during the waking condition. There is always a kind of vibration between the physical and etheric body and the Ego organization and astral body. There is an alternating vibration. And such people can be used as metal feelers—they feel the presence of metals. But the capacity to feel the presence of special metal substances in the earth is always based on a certain pathological condition.

Of course, if these things are only viewed technically and placed at the service of technical-earthly interests, it is, cruelly speaking, quite an indifferent matter whether people are slightly ill or not; even in other cases, one does not look so much at the means for bringing about this or that useful result. But from an inner standpoint, from the standpoint of a higher world conception, it is always pathological if people can perceive not only horizontally, in the environment of the earth, but also vertically, in a direct way, not through holes. What thus comes to expression, must, of course, be revealed in a different way. If we take a pen and write down something, this is contained in the ordinary life of thought; this must be lifeless. But the ordinary life of thought drowns in light (“verleuchtet”)—if I may use this expression in contrast to “darkens” (“verdunkelt”)—the perception coming from below; consequently, it is necessary to use different signs from those we use, for example, when we write or speak; different signs must be used when specific metal substances in the earth are perceived through a pathological condition. I observe, for example, that also water is a metal. Pathological people may actually be trained, not only to have unconscious perceptions, but also to give unconscious signs of these perceptions—for example, they can make signs with a rod placed in their hand.

What is the foundation of all this? It is based on the fact that there is a faint interruption between the Ego and astral body on the one hand, and the physical and etheric body on the other, so that the human being does not only perceive what is, approximately speaking, at his side, but by eliminating his physical body he becomes a sensory organ able to perceive the inside of the earth, without having to dig holes into it.

But when this direction exercises its influence, a direction which is normally that of feeling, then one cannot use the expressions which correspond to the thinking capacity. These perceptions are not expressed in words. They can only be expressed, as already indicated, through signs.

Similarly, it is possible to stimulate perceptions descending from above. They have a different inner character; they are no longer a perception of metals, but inspiration, conveying the movements or the constellation of the stars. In the same way in which the human being perceives the earth's constitution as rising up from below, he now perceives, descending from above, something which again arises through pathological conditions, when the Ego is in a more loose connection with the astral body. He then perceives, descending from above, something which really gives the world its division of time, the influence of time. This enables him to look more deeply into the world's course of events, not only in regard to the past, but also in connection with certain events which do not flow out of man's free will, but out of the necessity guiding the world's events. He is then able to look, as it were, prophetically into the future. He casts a gaze into the chronological order of time.

With these things I only wished to indicate that through certain pathological conditions it is possible for man to extend his perceptive capacity. In a sound and healthy way this is done through imagination and inspiration.

Perhaps the following may explain what constitutes sound and unsound elements in this field. For a normal person it is quite good if he has—let us say—a normal sense of smell. With a normal sense of smell he perceives objects around him through smell; but if he has an abnormal sense for any smelling object in his environment, he may suffer from an idiosyncrasy, when this or that object is near him. There are people who really get ill when they enter a room in which there is just one strawberry; they do not need to eat it. This is not a very desirable condition. It may, however, occur that someone who is not interested in the person, but in the discovery of stolen strawberries, or other objects which can be smelled, might use the special capacity of that person.

If the human sense of smell could be developed like that of dogs, it would not be necessary to use police dogs, for people could be used instead. But this must not be one. You will therefore understand me when I say that the perceptive capacity for things coming from below and from above should not be developed wrongly, so as to be connected with pathological conditions, for these are positively destructive for man's whole organization.

To train people to sense the presence of metals would therefore be the same as training them to be bloodhounds, police dogs, except that here—if I may use this expression—the humanly punishable element is far more intensive. For only through pathological conditions can such things appear in this or that person. All the things which generally come towards you in an ignorantly confused and nebulous way, will be understood in regard to their theory, and also by judging them as they have to be judged, within man's whole connection with the world. This is one aspect of the matter.

The other aspect is that there is also a right application of such a knowledge. A person who is endowed with the imaginative power of knowledge, must not use the imaginative forces of the astral body, located in the region of the heart, to procure gold. He may, however, apply these forces to recognize the construction, the true tasks, the inner essence of the heart itself. He may apply them in the meaning of human self-knowledge. In physical life this also corresponds to the right application of—let us say—the sense of smell, of sight, and so forth. We learn to know every organ in man when we are able to put together what we discern as coming from below or from above.

For example, you learn to know the heart when you recognize the gold contained in the earth, which sends out streams that may be perceived by the heart, and when, on the other hand, you recognize the current of will descending from the sun; that is to say, when you recognize the counter-current of the sun current in the will. If you unite these two streams, the joint activity of the sun's current from above, streaming down from the sun's zenith, and of the gold perceived below—if the gold contained in the earth stirs your imagination, and the sun your inspiration, you will obtain knowledge of the human heart, heart knowledge. In a similar way it is possible to gain knowledge of the other organs. Consequently, if the human being really wants to know himself, he must draw the elements of this knowledge from the influences coming from the cosmos.

This leads us to a sphere which indicates even more concretely than I have done on previous occasions man's connection with the cosmos. If you add to this the lectures which I have just concluded on the development of natural science in more recent times, you will gather, particularly from yesterday's lecture, that on the present stage of natural science man learns to know essentially lifeless substance, dead matter. He does not really learn to know himself, his own reality, but only his lifeless part. A true knowledge of man can only arise from the joint perception of the lifeless organs which we recognize in man, the organs in their lifeless state, and all we are able to recognize from below and from above in connection with these organs.

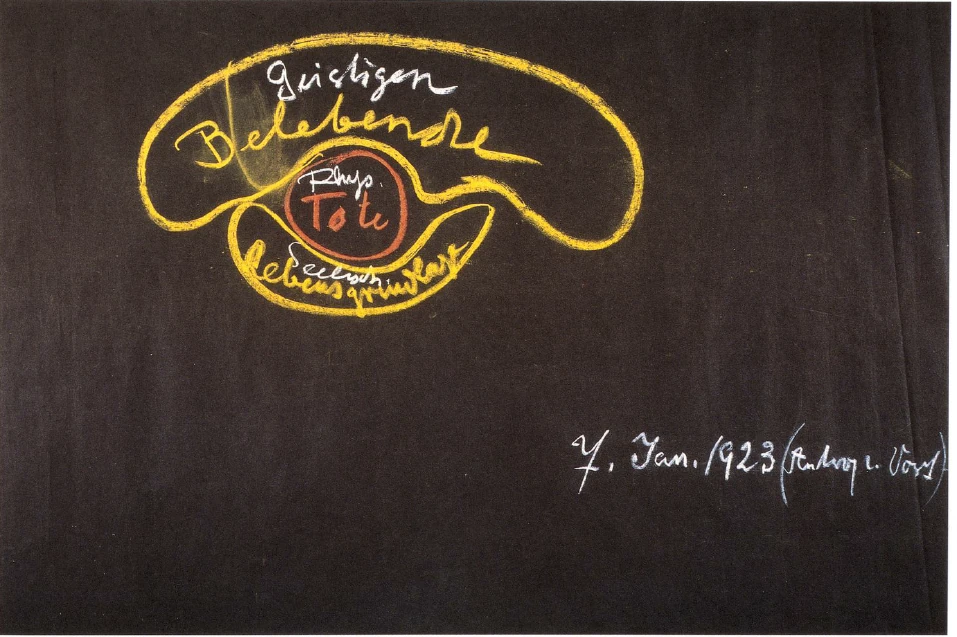

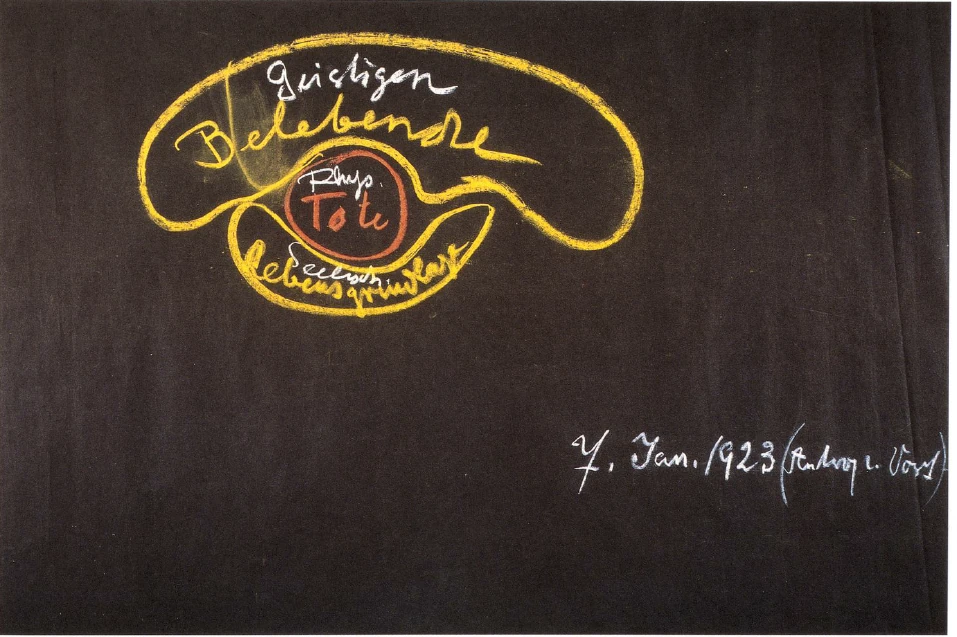

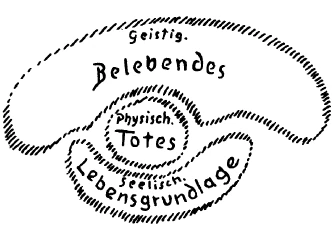

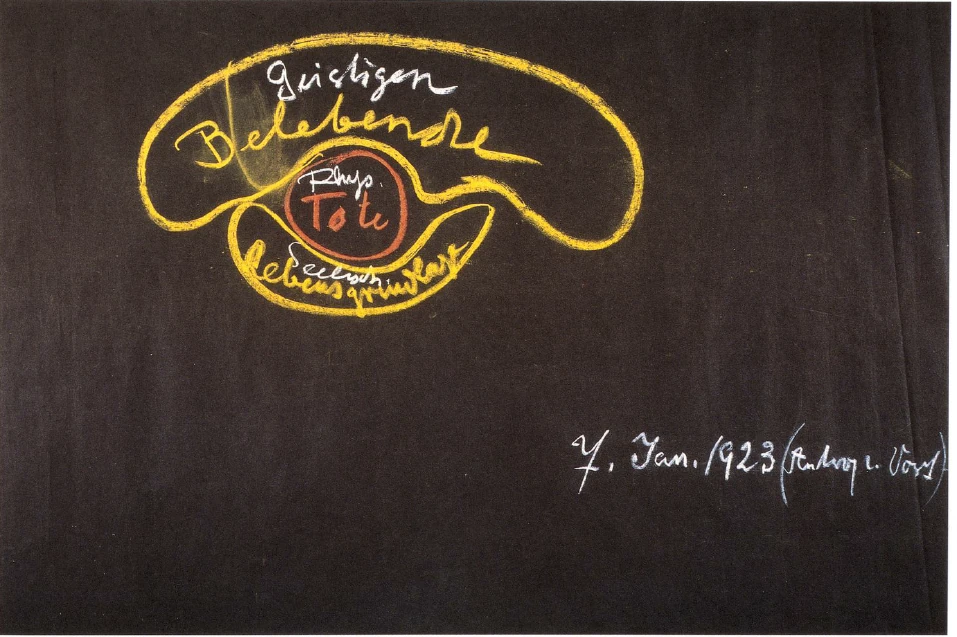

This leads to a knowledge based on full consciousness. An earlier, more instinctive knowledge was based upon an interpolation of the astral body which was different from that of today. Today the astral body is interpolated in such a way that man, as an earthly human being, may become free. This entails that he should recognize in the first place what is dead, and this pertains to the present, then the life foundation of the past through that which rises up from below—from the earth's metals—and finally the life-giving forces descending from above as star influences and star constellations.

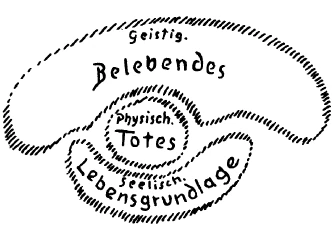

A true knowledge of man will have to seek in every organ this threefold essence: the lifeless or physical, the basis of life or the psychical, and the life-giving, vitalizing forces, or the spiritual.

Everywhere in human nature, in every detail connected with it, we shall therefore have to seek the physical-bodily, the psychical, and the spiritual. Logically, its point of issue will have to be gained from a true estimate of the results so far obtained in the field of natural science. It is necessary to see that the present stage of natural science leads us everywhere to the grave of the earth and that the living essence must be discovered and lifted out of the earth's grave.

We discover this by perceiving that modern spiritual science must endow old visions and ideas (Ahnungen) with life. For these always existed. In these days I have given advice to people working in different spheres; I would advise those studying history of literature that when they speak of Goetheanism, they should keep to Goethe's ideas expressed in the second part of “Wilhelm Meister”, in “Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahren”, where we find the description of a woman who is able to participate in the movements of the stars, owing to a pathological condition of soul and spirit. At her side we find an astronomer. And she is confronted by another character, by the woman who is able to feel the presence of metals. And at the side of this woman we find Montanus, the miner, the geologist. This contains a profound foreboding, far profounder than the truths in physics discovered since Goethe's time in the field of natural-scientific development, great as they are, for these natural-scientific truths pertain to man's circumference. But in the second part of “Wilhelm Meister” Goethe drew attention to something pertaining to the worlds with which man is connected—with the stars above, with the earth's depths below.

Many things of this kind may be found, both in the useful fields and in the luxury fields of science. But also these things will only be drawn to the surface as real treasures of knowledge, when Goetheanism, on the one hand, and spiritual science on the other, will be taken so earnestly that many things of which Goethe had an inkling will be illumined by spiritual science; and also spiritual science may thus change into something giving us a historical sense of pleasure when we see that Goethe had a kind of idea of things which now arise in form of knowledge, and which he elaborated artistically in his literary works.

With all these things, however, I wish to point out that when we speak of scientific strivings within the anthroposophical movement, these should be followed with that deep earnestness which does not bring with it the danger of Anthroposophy being deduced from modern chemistry, or modern physics, modern physiology, and so forth, but which includes the single branches of science in the real stream of living anthroposophical knowledge. One would like to hear of chemists, physicists, physiologists, medical men speaking in an anthroposophical way. For it leads to no progress if specialists succeed in forcing anthroposophy to speak chemically, physically or physiologically. This would only rouse opposition, whereas there should at last be a progress, evident in the fact that Anthroposophy reveals itself as Anthroposophy also to these specialists, and not as something which is taken in accordance with its terminology, so that terminologies are thrown over things which one already knows, even without Anthroposophy. It is the same whether anthroposophical or other terminologies are applied to hydrogen, oxygen, etc., or whether one adheres to the old terminologies. The essential thing is to take in Anthroposophy with one's whole being, then one becomes a true Anthroposophist, also as a chemist, physiologist, physician, etc.

In these lectures, in which I was asked to describe the history of scientific thought, I wished to bring, on the basis of a historical contemplation, truths that may bear fruit. For the anthroposophical movement absolutely needs to become fruitful, really fruitful, in many different fields.

Dritter Vortrag

Ich möchte heute innerhalb des veranstalteten Kurses eine Betrachtung anschließen an das Vorangehende, die allerdings etwas weiter hergeholte Ergebnisse der Geisteswissenschaft über den Menschen bringen soll. Ergebnisse, welche zeigen sollen, wie der Mensch in das Weltenall hineingestellt ist. Wir sprechen vom Menschen so, daß wir zunächst den Blick auf seine physische Organisation richten, dann auf das, was sich der geistigen Forschung enthüllt, den Äther- oder Lebensleib, den astralischen Leib und die Ich-Organisation. Aber wir verstehen diese Gliederung des Menschen noch nicht, wenn wir einfach diese Dinge in einer Reihenfolge aufzählen, denn ein jedes dieser Glieder ist in einer andern Weise in das Weltenall eingeordnet. Und nur dann, wenn wir die Einordnung der verschiedenen Glieder in das Weltenall verstehen, können wir uns überhaupt eine Vorstellung von der Stellung des Menschen im Universum machen.

Wenn wir den Menschen betrachten, wie wir ihn vor uns haben, so sind diese vier Glieder der menschlichen Natur in einer zunächst ununterscheidbaren Weise ineinandergefügt, zu einer Wechselwirkung vereinigt, und um sie zu verstehen, muß man sie gewissermaßen erst auseinanderhalten, jedes für sich in seinem besonderen Verhältnisse zum Weltenall betrachten. Wir werden, nicht in einer umfassenden Weise, aber von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus eine solche Betrachtung anstellen können, wenn wir dies in der folgenden Weise tun.

Lenken wir den Blick auf das mehr Peripherische des Menschen, auf das Äußere, auf die Umgrenzung. Da begegnen uns zunächst die Sinne. Wir wissen allerdings aus andern anthroposophischen Betrachtungen, daß wir gewisse Sinne erst entdecken, wenn wir gewissermaßen unter die Oberfläche der menschlichen Form, in das menschliche Innere hineingehen. Aber im wesentlichen würden wir auch die Sinne, welche uns von unserem eigenen Inneren unterrichten, zunächst auf eine sehr unbewußte Art in ihrem Ausgangspunkte, eben auf der Innenseite der Oberfläche des Menschen zu suchen haben. So daß man sagen kann, alles, was Sinn ist am Menschen, ist an der Oberfläche zu suchen. Man braucht nur einen der auffälligsten Sinne ins Auge zu fassen, zum Beispiel das Auge selbst oder das Ohr, und man wird finden, daß der Mensch gewisse Eindrücke von außen haben muß. Wie es sich mit ihnen wirklich verhält, das muß ja natürlich immer erst ersehen werden in einer eingehenderen Betrachtung, in einer eingehenderen Forschung, die wir für manche Sinne auch schon hier in diesem Raum angestellt haben. Aber so, wie sich die Dinge im Alltagsleben darstellen, kann man etwa sagen: Ein solcher Sinn, wie das Auge oder das Ohr, nimmt durch äußere Eindrücke die Dinge wahr.

Nun ist die Stellung des Menschen im Irdischen so, daß leicht zu ersehen ist, daß man die Hauptrichtung, in der die Wirkungen der Dinge eintreffen, damit er zu sinnlichen Wahrnehmungen kommt, annähernd «horizontal» nennen könnte. Eine genauere Betrachtung würde auch zeigen, daß die Behauptung, die ich jetzt getan habe, restlos richtig ist. Denn wenn es scheint, als ob wir in einer andern Richtung wahrnehmen würden, so beruht das bloß auf einer Täuschung. Es muß jede Wahrnehmungsrichtung zuletzt in die Horizontale fallen. Und die Horizontale ist diejenige Linie, welche parallel zur Erde ist. Wenn ich also schematisch zeichne, so müßte ich “sagen: Ist das die Erdoberfläche und darauf der wahrnehmende Mensch, so ist die Hauptrichtung seines Wahrnehmens diese, welche mit der Erde parallel ist (Zeichnung S. 42, links). In dieser Richtung verlaufen die Richtungen all unseres Wahrnehmens.

Und wenn wir den Menschen betrachten, so werden wir auch unschwer sagen können: Die Wahrnehmungen kommen von außen, gehen gewissermaßen von außen nach innen. — Was bringen wir ihnen von innen entgegen? Wir bringen ihnen von innen entgegen das Denken, die Vorstellungskraft. Sie brauchen sich diesen Vorgang nur vor Augen zu führen. Sie werden sich sagen: Wenn ich durch das Auge wahrnehme, kommt der Eindruck von außen, die Vorstellungskraft, die kommt von innen (Zeichnung S. 42, rechts). Von außen kommt der Eindruck, wenn ich den Tisch sehe. Daß ich den Tisch dann auch in der Erinnerung mit Hilfe einer Vorstellung behalten kann, dazu kommt die Kraft des Vorstellens von innen. So daß wir also sagen können: Wenn wir uns schematisch einen Menschen vorstellen, so haben wir die Richtung des Wahrnehmens von außen nach innen, die Richtung des Vorstellens von innen nach außen. Was wir da ins Auge fassen, bezieht sich auf die Wahrnehmungen des alltäglichen Lebens des Erdenmenschen, jenes Erdenmenschen, wie er sich in unserem gegenwärtigen Zeitalter der Erdenentwickelung äußerlich offenbart. Es ist das, was ich oben erwähnt habe, der Tatbestand des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins. Aber wenn Sie die anthroposophische Literatur durchgehen, werden Sie finden, daß es andere Bewußtseinsmöglichkeiten gibt als diejenigen, die eben für den Erdenmenschen im alltäglichen Leben vorhanden sind.

Nun versuchen Sie einmal, wenn auch nur annähernd und verschwommen, sich ein Bild zu machen von dem, was da durch den Erdenmenschen wahrgenommen wird. Sie sehen das, was auf Erden vorhanden ist, in Farben, hören es in Tönen, nehmen es in Wärmeempfindungen: wahr und so weiter. Sie schaffen sich Konturen für das, was wahrgenommen wird, so daß Sie die Dinge gestaltet wahrnehmen. Nun ist aber dasjenige, in dem wir uns da zusammen mit unserer Umgebung wissen, eben nur der Tatbestand des gewöhnlichen alltäglichen Bewußtseins. Es gibt eben andere Bewußtseinsmöglichkeiten, die beim Erdenmenschen mehr unbewußt bleiben, die in die Tiefen des Seelenlebens gedrängt sind, die aber für dieses menschliche Leben von einer ebenso großen, oft viel größeren Bedeutung sind als solche Bewußtseinstatsachen, die sich in dem erschöpfen, was ich bisher erwähnt habe.

Für die menschliche Konstitution, für das, was der Mensch auf Erden ist, da ist dasjenige, was innerhalb der Erdoberfläche ist, ebenso wichtig wie das, was im Umkreise der Erde ist. Der Umkreis der Erde, was um die Erde herum ist, das ist es eben, was für die gewöhnlichen Sinne wahrnehmbar ist, was durch die der Sinneswahrnehmung entgegenkommende Vorstellungskraft nun einmal das Bewußtsein des gewöhnlichen Erdenmenschen werden kann.

Aber betrachten wir zunächst das Innere der Erde. Eine gewöhnliche Überlegung wird Ihnen sagen können, daß das Innere der Erde sich dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein verschließt. Gewiß, wir können eine kurze Strecke in die Erde hineingraben und dann in den Löchern, sagen wir in Bergwerken, ebenso beobachten, wie wir auf der Oberfläche beobachten. Aber das ist nicht anders, als wenn wir vom Menschen den Leichnam betrachten. Wenn wir einen Leichnam beobachten, so beobachten wir ja nur etwas, was eigentlich nicht mehr der ganze Mensch ist, was ein Rest des ganzen Menschen ist; wer diese Dinge richtig anschauen kann, muß sogar sagen: was das Gegenteil des Menschen ist. Das Wirkliche des Erdenmenschen ist der lebendig herumgehende Mensch, und dem ist angemessen dasjenige, was er an Knochen, Muskeln und so weiter in sich trägt. Dem lebendigen Menschen entspricht als eine Wahrheit der Knochenbau, der Muskelbau, der Nervenbau, entsprechen Herz, Lunge und so weiter. Wenn ich den Leichnam vor mir habe, so entspricht das ja nicht mehr dem Menschen. An dem Gebilde, das ich als Leichnam vor mir habe, gibt es gar keinen Grund, daß eine Lunge, ein Herz oder ein Muskelsystem da sein soll. Daher zerfallen sie auch. Sie erhalten eine Weile die Form, die ihnen aufgedrängt ist. Aber ein Leichnam ist eigentlich eine Unwahrheit, denn so, wie er ist, kann er nicht bestehen, muß er sich auflösen. Er ist keine Wirklichkeit. Ebenso ist das keine Wirklichkeit; was ich im Inneren der Erde finde, wenn ich hineingrabe, weil die geschlossene Erde auf den daraufstehenden Menschen anders wirkt, als das, was der Mensch, wenn er auf der Erde steht, als die Umgebung der Erde durch seine Sinne betrachtet. Sie können sagen, wenn Sie zunächst die Sache seelisch betrachten: Die Umgebung der Erde ist in der Lage, auf die gewöhnlichen Sinne des Menschen zu wirken und begriffen zu werden durch das Vorstellungsvermögen des gewöhnlichen Erdenbewußtseins. Das, was im Inneren der Erde ist, wirkt auch auf den Menschen, aber es wirkt nicht in der horizontalen Richtung, es wirkt von unten nach oben. Es geht durch den Menschen durch (Zeichnung S. 46, links, roter Pfeil). Und während des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins nimmt der Mensch dasjenige nicht in derselben Weise wahr, was da von unten nach oben wirkt, wie er durch seine gewöhnlichen Sinne das wahrnimmt, was in seiner Erdenumgebung ist. Denn wurde der Mensch in derselben Weise das, was von der Erde heraufwirkt, wahrnehmen, wie er dasjenige wahrnimmt, was in der Erdenumgebung ist, dann würde er gewissermaßen eine Art Auge oder eine Art Getast haben müssen, um hineinzugreifen in die Erde, ohne daß er ein Loch hineingräbt, um die Erde ebenso zu durchgreifen, wie man die Luft durchgreift, wenn man etwas angreift, oder wie man die Luft durchschaut, wenn man etwas anschaut. Wenn Sie durch die Luft schauen, graben Sie nicht ein Loch durch die Luft. Wenn Sie ein Loch durch die Luft graben und dann erst anschauen würden, so würden Sie die Umgebung so anschauen, wie Sie in einem Bergwerk die Erde anschauen. Wenn Sie also nicht ein Loch zu graben brauchten, um das Innere der Erde zu sehen, dann müßten Sie ein Sinnesorgan haben, welches sehen kann, ohne Löcher in die Erde zu graben, für welches also die Erde, so wie sie ist, durchsichtig oder durchfühlbar ist. Das ist sie in gewisser Beziehung für den Menschen. Aber dem Menschen kommen im gewöhnlichen Erdenleben die Wahrnehmungen, um die es sich handelt, nicht zum Bewußtsein. Was der Mensch da nämlich wahrnehmen würde, das sind die differenzierten Metalle der Erde.

Denken Sie sich doch nur einmal, wieviel Metalle die Erde in sich enthält! Geradeso nun wie Sie in Ihrer Luftumgebung Tiere, Pflanzen, Mineralien, Kunstsachen der verschiedensten Art wahrnehmen, so nehmen Sie vom Inneren der Erde herauf Metalle wahr. Aber die Wahrnehmungen der Metalle würden, wenn sie Ihnen wirklich zum Bewußtsein kämen, eben nicht gegenständliche Wahrnehmungen sein, sondern sie würden Imaginationen sein. Und diese Imaginationen kommen auch fortwährend von unten in den Menschen herauf. Geradeso wie von der Horizontalen die Seheindrücke kommen, so kommen fortwährend von unten herauf die Metalleinstrahlungen, nicht die Sehwahrnehmungen von den Mineralien, sondern etwas von der inneren Natur der Mineralien wirkt durch den Menschen herauf zu Imaginationen, zu Bildern. Der Mensch nimmt diese Bilder nicht wahr, sondern sie schwächen sich ab. Sie werden gewissermaßen unterdrückt, weil das Erdenbewußtsein des Menschen nicht so ist, daß er die Imaginationen wahrnehmen kann. Sie schwächen sich ab zu Gefühlen.

Wenn Sie sich zum Beispiel alles Gold denken, das in der Erde . irgendwie in Klüften und so weiter ist, so nimmt tatsächlich Ihr Herz ein Bild wahr, welches dem Golde in der Erde entspricht (Zeichnung S. 46, links, lila). Nur ist dieses Bild eben Imagination, und deshalb wird es vom gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht wahrgenommen, sondern zu einem bloßen innerlichen Lebensgefühl abgestumpft, zu einem Lebensgefühl, das der Mensch noch nicht einmal deuten kann, geschweige denn, daß er das entsprechende Bild wahrnehmen würde. Ebenso ist es mit andern Organen, zum Beispiel nimmt die Leber alles Zinn der Erde in einem bestimmten Bilde wahr und so weiter.

Das alles sind unterbewußte Eindrücke, die sich nur im allgemeiin horizontaler Weise die Wahrnehmungen von der Erdenumgebung kommen und ihnen von innen die Vorstellungskraft entgegenkommt, so kommen von unten herauf die Metallwahrnehmungen, speziell die Metallwahrnehmungen, und ihnen kommt, geradeso wie den gewöhnlichen Wahrnehmungen die Vorstellungskraft entgegenkommt, für das Bewußtsein das Fühlen entgegen (Zeichnung links, gelbe Pfeile). Aber den Menschen des heutigen Erdenlebens bleibt es chaotisch und unklar. Es kommt eben nur ein allgemeines Lebensgefühl heraus.

Würde dieser Erdenmensch Begabung haben für Imagination, so könnte er eben wissen, daß sein Wesen auch mit dem Metallischen der Erde zusammenhängt. Eigentlich ist jedes menschliche Organ ein Sinnesorgan, und wenn wir es zu etwas anderem gebrauchen oder wenn es scheint, daß wir es zu etwas anderem gebrauchen, so ist es doch ein Sinnesorgan. Sein Gebrauch im Erdenleben ist eigentlich nur ein stellvertretender. Mit allen Organen, die der Mensch hat, nimmt er eigentlich irgend etwas wahr. Der Mensch ist ganz und gar ein großes Sinnesorgan, und wiederum als solches groRes Sinnesorgan spezifiziert, differenziert in seine einzelnen Organe als besondere Sinnesorgane.

Der Mensch hat also von unten herauf Metallwahrnehmungen, und der Metallwahrnehmung entspricht das Gefühlsleben. Unsere Gefühle haben wir geradeso als Gegenwirkung gegen alles, was metallisch aus der Erde auf den Menschen wirkt, wie wir unsere Vorstellungskraft haben als Gegenwirkung gegen alles, was aus der Umgebung in die Sinneswahrnehmung hereindringt. Aber ebenso wie der Mensch von unten herauf die Metallwirkungen hat, so wirkt von oben nach unten aus dem Weltenraum herein dasjenige, was Bewegung und Form der Himmelskörper ist. Wie wir in unserer Umgebung also die Sinneswahrnehmung haben, so haben wir wiederum für ein Bewußtsein, das als inspiriertes Bewußtsein wirken würde, Inspirationen von jeder Planetenbewegung, von der Fixsternkonstellation. Und so wie wir die Vorstellungskraft entgegenströmen lassen den gewöhnlichen Sinneswahrnehmungen, so lassen wir den Bewegungen der Himmelskörper entgegenströmen eine Kraft (siehe Zeichnung rechts, gelbe Pfeile), die den Sterneindrücken entgegengesetzt ist, und diese Kraft ist die Willenskraft. Was in unserer Willenskraft liegt, würden wir, wenn wir mit dem inspirierten Bewußtsein rechneten, eben als Inspiration wahrnehmen.

Wenn wir den Menschen in dieser Weise studieren, dann sagen wir uns also: Wir finden in seinem Erdenbewußtsein zunächst dasjenige, in dem er am meisten wach ist, das Vorstellungs-Sinnesleben. Eigentlich sind wir nur in diesem Vorstellungs-Sinnesleben im gewöhnlichen Erdenbewußtsein ganz wach. Dagegen ist nur traumhaft vorhanden unser Gefühlsleben. Unser Gefühlsleben ist nicht intensiver, nicht heller als Träume sind, nur sind Träume Bilder, während das Gefühlsleben die allgemeine, durch das Leben bestimmbare Seelenverfassung, eben die des Fühlens, ist. Aber diesem Fühlen liegt zugrunde die Metallwirkung der Erde. Noch tiefer — das habe ich öfter auseinandergesetzt —, noch dumpfer ist das Bewußtsein des Willens. Der Mensch weiß nicht, was sein Wille in ihm eigentlich ist. Ich habe es oft so ausgesprochen, daß ich sagte: Der Mensch hat

den Gedanken, er strecke den Arm aus, er greife mit der Hand etwas. Diesen Gedanken kann er mit seinem wachen Bewußtsein haben. Dann sieht er wiederum den Tatbestand des Ergreifens. Aber was eigentlich dazwischen liegt, dieses Hineinschießen des Willens in die Muskeln und so weiter, das bleibt dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein ebenso verborgen wie die Erlebnisse des tiefen traumlosen

Schlafes. Im Fühlen traumen wir, im Wollen schlafen wir. Aber dieser im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein schlafende Wille ist eben auch dasjenige, was der Mensch auf die Sterneindrücke geradeso entgegnet, wie er in seinen Vorstellungen auf die Sinneseindrücke des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins entgegnet. Und was der Mensch in seinen Gefühlen träumt, das ist die Gegenwirkung auf die Metallwirkung der Erde.

Wenn wir als heutiger Erdenmensch wachen, so nehmen wir die Dinge um uns herum wahr. Unser Vorstellungsvermögen wirkt ihnen entgegen. Dazu brauchen wir unseren physischen und unseren Ätherleib. Ohne den physischen und ohne den Ätherleib können wir nicht die Kräfte entwickeln, welche in der horizontalen Richtung wahrnehmend, vorstellungsmäßig wirken. So daß wir, wenn wir uns das schematisch vorstellen wollen, sagen können: physischer Leib, Ätherleib erfüllen sich für das Tagesbewußtsein mit den Eindrücken der Sinne und des Vorstellungsvermögens (siehe Zeichnung, gelb). Wenn der Mensch nun schläft, so sind ja sein astralischer Leib und seine Ich-Organisation außerhalb. Sie sind es nun, welche die Eindrücke von unten und von oben bekommen. Sie sind es, das Ich und der astralische Leib, die eigentlich schlafen in dem, was von der Erde aus Metallausströmung ist und was von oben herunter die Strömungen der Planetenbewegungen und der Fixsternkonstellationen sind. Was so in der Umgebung der Erde erzeugt wird, was aber in der Richtung der Horizontale keine Kraftwirkung hat, sondern als Kräfte von oben nach unten wirkt, das ist dasjenige, in dem wir während der Nacht sind.

Wenn Sie den Versuch machen würden, vom gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein zur Imagination zu kommen, so daß das wirkliche imaginierende Bewußtsein da ist, so müßte das, vermöge des gegenwärtigen Zeitalters der Menscheitsentwickelung, so sein, daß gleichmäßig alle menschlichen Organe von diesem Bewußtsein ergriffen werden. Es darf nicht etwa, sagen wir, bloß das Herz ergriffen werden, sondern es müssen alle Organe gleichmäßig ergriffen werden. Ich sagte vorhin, das Herz nimmt das Gold wahr, das in der Erde ist. Aber es kann niemals allein das Gold wahrnehmen, denn die Sache ist so: Solange das Ich und der astralische Leib mit dem physischen Leib und mit dem Ätherleib in einer solchen Verbindung sind, wie das beim normalen wachenden Menschen der Fall ist, so lange kann ja überhaupt nichts von einer Wahrnehmung bewußt werden. Erst dann, wenn das Ich und der astralische Leib, wie das bei der Imagination der Fall ist, bis zu einem gewissen Grade selbständig gemacht werden, so daß sie von dem physischen und dem Ätherleib unabhängig werden, dann können wir sagen: Es werden der astralische Leib und die Ich-Organisation in der Nähe der Herzgegend fähig, etwas von diesem Ausströmen des Metallischen in der Erde zu wissen. Und da kann man sagen: Das Zentrum für die Einwirkungen der Goldausströmung liegt im astralischen Leibe in der Gegend des Herzens. Das Herz nimmt wahr, weil der astralische Leib, der dieser Partie, dem Herzen, zugehört, das eigentlich Wahrnehmende ist. Das physische Organ nimmt nicht wahr, sondern .es nimmt der astralische Leib wahr.

Wenn nun das imaginative Bewußtsein erworben wird, dann muß der gesamte astralische Leib und auch die gesamte Ich-Organisation in einem Zustande sein, daß diejenigen Partien wahrnehmen, die allen menschlichen Organen entsprechen. Das heißt, der Mensch nimmt dann die gesamte Metallität der Erde, allerdings in Differenzierungen, wahr. Einzelheiten kann er darin nur wahrnehmen, wenn er sich besonders darauf trainieren und es zu seinem besonderen okkulten Studium machen würde, die Metallität der Erde kennenzulernen. Diese Erkenntnis ist etwas, was für die gegenwärtige Zeitepoche nicht eine gewöhnliche Erkenntnis für den Menschen sein soll. Der Mensch sollte diese Erkenntnis heute nicht in den Dienst seines nützlichen und nutzbringenden Lebens stellen. Weil dieses Weltgesetz ist, würde sofort, wenn jemand diese Metallerkenntnis der Erde nur im geringsten in den Dienst des gewöhnlichen nutzenden Lebens stellen wollte, die imaginative Erkenntnis genommen werden.

Es kann aber vorkommen, daß durch krankhafte Zustände irgendwo im Menschen oder auch im allgemeinen der innige Zusammenhang, der zwischen dem astralischen Leib und den Organen eigentlich da sein sollte, unterbrochen ist, so daß der Mensch gewissermaßen in einer sehr leisen Art wachend schläft. Wenn er wirklich schläft, so ist auf der einen Seite sein physischer Leib und sein Ätherleib, auf der andern Seite sein astralischer Leib und sein Ich auseinander. Aber es gibt auch ein so leises Schlafen, daß der Mensch kaum bemerkbar benommen herumgeht in einem Zustande, der einem sogar vielleicht sehr interessant ist, weil solche Menschen merkwürdig «mystisch» aussehen, so mystische Augen haben und dergleichen. Das kann davon herrühren, daß ein ganz leises Schlafen auch während des Wachens vorhanden ist. Es ist immer eine Art Vibrieren des physischen und des Ätherleibes gegenüber der Ich-Organisation und dem astralischen Leibe. Das vibriert so hin und her. Und solche Menschen sind dann geeignet, als Metallfühler gebraucht zu werden. Aber es beruht die Fähigkeit, da oder dort spezielles Metallisches im Irdischen zu fühlen, immer auf einer gewissen krankhaften Anlage. Natürlich, sobald man die Sache bloß technisch anschaut und in den Dienst des Technisch-Irdischen stellt, kann es einem ganz gleichgültig sein -— wenn ich grausam sprechen will -—, ob die Leute ein bißchen krank sind oder nicht. Man sieht ja auch sonst nicht so sehr auf die Mittel, durch die man dieses oder jenes Nützliche bewerkstelligt. Aber innerlich angesehen, vom Standpunkt einer höheren Weltauffassung, ist es immer etwas Krankhaftes, wenn der Mensch dazukommt, auf diese Weise nicht nur in der Horizontalen in der Erdenumgebung, sondern nach unten hin wahrzunehmen, und zwar nicht durch Löcher, sondern direkt. Dann ist es natürlich notwendig, daß der Mensch dasjenige, was er da ausdrückt, auch nicht auf gewöhnliche Weise kundgibt. Wenn man eine Feder nimmt und etwas aufschreibt, da ist das gewöhnliche Vorstellungsleben darin, das muß tot sein. Aber dieses gewöhnliche Vorstellungsvermögen, das — wenn ich mich des Ausdrucks bedienen darf: verleuchtet, als Gegensatz zum Verdunkeln -, das verleuchtet die Wahrnehmung, die von unten heraufkommt. Und so ist es notwendig, daß man andere Zeichen macht, als wenn man schreibt oder spricht, wenn man durch krankhafte Zustände speziell Metallisches in der Erde wahrnimmt. Ich bemerke, daß zum Beispiel Wasser auch ein Metall ist. Solche krankhaften Personen können gerade darauf trainiert werden, nicht bloß unbewußt wahrzunehmen, sondern für die Wahrnehmung auch unbewußt Zeichen zu machen. Wenn man solchen Menschen etwa eine Rute in die Hand gibt, dann machen sie damit die Zeichen. Worauf beruht das Ganze? Es beruht eben darauf, daß jene leise Unterbrechung zwischen dem Ich und dem astralischen Leib auf der einen Seite und dem physischen Leib und dem Ätherleib auf der andern Seite da ist, und dadurch der Mensch nicht nur dasjenige wahrnimmt, was neben ihm ist, approximativ gesprochen, sondern, indem er seinen physischen Leib ausschaltet, sich zum Sinnesorgan macht und das Innere der Erde wahrnimmt, ohne daß er Löcher hineinmacht. Aber wenn diese Richtung wirkt, die sonst nur die Normalrichtung des Fühlens ist, dann kann er sich auch nicht so ausdrücken, wie es dem Vorstellungsvermögen entspricht. Er spricht es nicht in Worten aus. Er kann es nur in der Weise, wie ich angedeutet habe, in Zeichen aussprechen.

In einer ähnlichen Weise aber kann angeregt werden, daß der Mensch die Wahrnehmung hat, die von oben herunterkommt. Sie hat einen andern inneren Charakter. Sie ist nun nicht Metallwahrnehmung, sondern sie ist Inspiration, welche Sternbewegungen oder Sternkonstellationen wiedergibt. Und da nimmt der Mensch dann ebenso, wie er von unten her die Konstitution der Erde wahrnimmt, von oben herunter dasjenige wahr, was also auch nur durch diese krankhaften Zustände eintritt, wenn in diesem Falle das Ich vom astralischen Leibe etwas abgelockert ist. Er nimmt dann von oben herunter dasjenige wahr, was eigentlich der Welt die Zeiteinteilung, den Zeitenfluß gibt. Dadurch sieht er tiefer hinein in das Geschehen der Welt, nicht nur nach der Vergangenheit, sondern auch nach gewissen Ereignissen, die allerdings nicht solche sind, die aus dem freien menschlichen Willen fließen, sondern die aus der Notwendigkeit der Weltenordnung fließen. Er sieht dann gewissermaßen prophetisch in die Zukunft, er sieht in die Zeitenordnung hinein.

Ich wollte Ihnen durch diese Dinge nur andeuten, daß durch gewisse krankhafte Zustände allerdings der Mensch sein Wahrnehmungsvermögen erweitern kann. In gesunder Weise wird es durch Imagination und Inspiration erweitert. Was auf diesem Felde das Gesunde und Krankhafte bedeutet, das wird Ihnen vielleicht durch folgendes klarwerden: Es ist für einen normalen Menschen ganz gut, wenn er, sagen wir, auch einen normalen Geruch hat. Wenn ein Mensch einen normalen Geruch hat, dann wird er die Gegenstände um sich herum durch den Geruch wahrnehmen. Aber wenn er für irgendwelche Dinge der Umgebung, die riechen, einen abnormalen Geruch hat, so kann es passieren, daß er an Idiosynkrasie erkrankt, wenn diese oder jene Gegenstände in seiner Umgebung sind. Es kann Menschen geben, die zum Beispiel wirklich durch den Geruch ganz krank werden, wenn sie in ein Zimmer gehen, in dem eine einzige Erdbeere ist; sie brauchen sie gar nicht zu essen. Das ist nicht gerade ein wünschenswerter Zustand. Dennoch könnte es unter Umständen geschehen, daß jemand, der nicht auf den Menschen sieht, sondern vielleicht darauf, daß irgendwo durch den Menschen gestohlene Erdbeeren gefunden werden könnten, oder überhaupt gestohlene zu riechende Gegenstände, dieses besondere Vermögen des Menschen verwendet. Wenn der Mensch sein Riechvermögen so ausbilden könnte wie die Hunde, so brauchte man keine Polizeihunde, sondern man könnte den Menschen dazu verwenden.

Aber man darf das nicht tun. Sie werden daher verstehen, wenn ich sage, daß auch das Wahrnehmungsvermögen nach unten und nach oben nicht in einer unrichtigen Weise, so daß es mit dem Krankhaften zusammenhängt, entwickelt werden darf, denn das ist so beschaffen, daß es direkt zerstörerisch für des Menschen ganze Organisation ist. Also Metallfühler geradezu auszubilden, zu trainieren, würde ganz gleichkommen dem Unternehmen, Menschen als Polizeihunde, als Spürhunde auszubilden. Nur daß das rein Menschlich-Sträfliche hier in einer viel intensiveren Weise vorliegt. Aber eben nur durch krankhafte Zustände kann bei dem einen oder andern Menschen so etwas auftreten.

Sie werden alle Dinge, die Ihnen in einer zumeist laienhaft verworrenen, nebulosen Weise zukommen, sowohl hinsichtlich ihres Theoretischen verstehen können, wie Sie ermessen können, wie diese Dinge im ganzen Weltzusammenhang des Menschen bewertet werden müssen. Das ist die eine Seite der Sache.

Aber die andere Seite der Sache ist diese, daß es auch eine gerechte Anwendung solcher Erkenntnisse gibt. Um den Menschen Gold zu verschaffen, darf derjenige, der die imaginative Erkenntnis besitzt, nicht die imaginative Kraft des astralischen Leibes anwenden, die in der Herzgegend sitzt. Aber er kann sie anwenden, um die Konstruktion, die wahren Aufgaben, die Innerlichkeit des Herzens selber zu erkennen. Er kann sie anwenden im Sinne der menschlichen Selbsterkenntnis. Das entspricht auch im physischen Leben der gerechten Anwendung, sagen wir des Geruchsvermögens oder des Sehvermögens oder dergleichen. Und so lernt man jedes Organ des Menschen erkennen, indem man zusammenzufügen vermag das, was man von unten, und das, was man von oben erkennt.

Sie lernen zum Beispiel das Herz erkennen, wenn Sie den Goldgehalt der Erde, wie er ausströmt und durch das Herz wahrgenommen werden kann, erkennen, und wenn Sie auf der. andern Seite die Willensströmung von der Sonne oben herein, das heißt, die Gegenströmung von der Sonnenströmung als Wille erkennen, so daß im Zusammenwirken der Sonnenströmung von oben, von der Zenitstellung der Sonne aus, mit der Golderkenntnis von unten, indem Sie diese zwei zusammenbringen, Sie sich von dem Goldgehalt der Erde zur Imagination, von der Sonne aus zur Inspiration anregen lassen, dann bekommen Sie die Herzerkenntnis des Menschen. Und so die Erkenntnis der andern Organe. Der Mensch muß also tatsächlich, wenn er sich kennenlernen will, die Elemente dieser Erkenntnisse aus dem Kosmos auf sich einwirken lassen.

Wir haben damit ein Gebiet betreten, das nun in einer noch konkreteren Weise, als ich das manchmal schon früher getan habe, hinweist auf den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Kosmos. Wenn Sie dazu die Vorträge nehmen, die ich über die Entwickelung der Naturerkenntnis in der neueren Zeit abgeschlossen habe, so werden Sie gerade aus dem gestrigen Vortrage ersehen haben, wie es im wesentlichen das Tote ist, das der Mensch durch die gegenwärtige Stufe der Naturwissenschaft erkennt. Er erkennt sich’ selbst ja nicht, wie er in Wirklichkeit ist, sondern eigentlich hinsichtlich seines Toten. Und eine wirkliche Erkenntnis des Menschen wird erst erblühen aus dem Zusammenschauen dessen, was man am Menschen als tote Organe erkennt, als Organe in ihrer Torheit, mit dem, was man von oben und von unten für diese Organe erkennen. kann.

Dadurch erlangt man eine Erkenntnis mit vollem Bewußtsein. Früheres instinktives Erkennen war die Folge einer andern Einschaltung des astralischen Leibes in den ätherischen Leib, als sie heute der Fall ist. Heute ist die Einschaltung diese, daß der Mensch als Erdenmensch ein freier Mensch werden kann. Dazu ist aber notwendig, daß der Mensch erstens erkennt das tote Gegenwärtige, die Lebensgrundlage der Vergangenheit durch dasjenige, was von unten heraufkommt von der Metallizität der Erde, und das Belebende von oben als Sternenwirkungen und Sternenkonstellationen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 55).

Und bei jedem Organ wird eine wahre Menschenkenntnis suchen müssen diese Dreiheit - nach Totem oder Physischem, nach der Lebensgrundiage oder dem Seelischen, nach dem Belebenden oder dem Geistigen. Und so wird man bis in die Einzelheiten der menschlichen Natur überall suchen müssen nach dem PhysischKörperlichen, nach dem Seelischen, nach dem Geistigen. Und der Ausgangspunkt dafür muß vernünftigerweise gewonnen werden aus einer richtigen Einschätzung desjenigen, was wir als das bisherige Ergebnis der Naturwissenschaft erkannt haben. Es muß erkannt werden, daß uns der gegenwärtige Stand der Naturwissenschaft überall zu dem Erdengrabe hinführt und daß wir herausfinden müssen aus dem Erdengrab das Lebendige.

Das finden wir, wenn wir in der Tat gewahr werden, wie die neuere Geisteswissenschaft alte Ahnungen beleben muß. Ahnungen von diesen Dingen waren immer da. Ich habe in diesen Tagen den Arbeitenden auf den verschiedensten Gebieten Verschiedenes geraten. Ich möchte nun den Literaturhistorikern auch anraten, wenn sie von Goetheanismus reden wollen, sich doch einmal an die Goethesche Ahnung zu halten, die sie im zweiten Teil von «Wilhelm Meister, in «Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahren», finden, wo ein Wesen vorkommt, das durch einen krankhaften Seelen-Geisteszustand Sternbewegungen mitlebt. Ihr ist ein Astronom an die Seite gegeben. Aber diesem Wesen steht eine andere Person entgegen, die Metallfühlerin. Ihr ist der Montanus, der Bergmann, an die Seite gegeben, der Geologe. Darin liegt eine tiefe Ahnung, eine Ahnung, die viel tiefer ist als alles, was an physikalischen Wahrheiten seit Goethe in der naturwissenschaftlichen Entwickelung zutage getreten ist, so groß diese auch sind. Denn diese naturwissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse gehören dem Umkreise des Menschen an; Goethe hat hingedeutet im zweiten Teil seines «Wilhelm Meister», in «Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahren», auf dasjenige, was den Welten angehört, mit denen der Mensch nach oben hin zu den Sternen, nach unten hin in die Tiefe der Erde zusammenhängt.

Und von solchen Dingen können noch sehr viele gefunden werden sowohl in den nutzbringenden Wissenschaften wie in den Luxuswissenschaften. Aber auch diese Dinge werden erst als wirkliche Erkenntnisschätze gehoben werden, wenn man einmal den Goetheanismus auf der andern Seite so ernst nehmen wird, daß man manches, was bei Goethe Ahnung ist, durch Geisteswissenschaft erleuchtet, oder aber auch vielleicht das Geisteswissenschaftliche dadurch zu etwas umgestaltet, was einem eine gewisse historische Freude macht, indem man die Dinge, die jetzt als Erkenntnis auftreten, bei Goethe als eine Art Ahnung in romanhafter Form verarbeitet findet.

Durch alles das aber möchte ich eben darauf hindeuten, daß, wenn die Rede davon ist, daß wissenschaftliche Bestrebungen innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung gepflegt werden sollen, sie mit dem tiefen Ernst gepflegt werden sollen, der nicht die Anthroposophie in die Gefahr bringt, nach der heutigen Chemie oder der heutigen Physik oder der heutigen Physiologie und dergleichen abgeleitet zu werden, sondern der in den wirklichen Strom anthroposophisch lebendiger Erkenntnis die einzelnen Wissenschaften einbezieht. Hören möchte man, daß die Chemiker, daß die Physiker, daß die Physiologen, daß die Mediziner anthroposophisch reden. Denn das wird nicht weiterführen, daß die einzelnen Spezialisten dazu kommen, Anthroposophie zu zwingen, chemisch oder physikalisch oder physiologisch zu reden. Dadurch wird Anthroposophie doch nur Gegnerschaft erwecken, während endlich vorwärtsgekommen werden muß, indem die Anthroposophie sich auch für diese Spezialisten als Anthroposophie erweist, und nicht bloß als irgend etwas, was seiner Terminologie nach genommen wird, wo die einzelnen Termini hinübergestülpt werden über das, was man sonst auch schon hat. Es ist ganz gleichgültig, ob man anthroposophische oder andere Termini über den Wasserstoff oder über den Sauerstoff und so weiter stülpt, oder ob man bei den alten Termini bleibt. Worauf es ankommt, ist, mit seinem ganzen Menschen die Anthroposophie aufzunehmen. Dann wird man in der richtigen Weise Anthroposoph auch als Chemiker, als Physiologe, als Arzt sein.

Ich wollte gerade, daß dieser Kursus, für den man von mir verlangt hat, eine Darstellung der Geschichte naturwissenschaftlicher Denkweise zu geben, wirklich diejenige Erkenntnis aus dieser historischen Betrachtung bringt, die auch fruchtbar werden kann. Denn fruchtbar zu werden auf den verschiedensten Gebieten, wirklich fruchtbar, das hat die anthroposophische Bewegung durchaus nötig. Davon werde ich dann in meinem nächsten Vortrag für diejenigen, die dann da sein werden, weiter sprechen.

Third Lecture

Today I would like to follow up the previous lecture with an observation within the organized course, which, however, should bring somewhat more far-fetched results of spiritual science about man. Results which are intended to show how man is placed in the universe. We speak of man in such a way that we first look at his physical organization, then at that which reveals itself to spiritual research, the etheric or life body, the astral body and the ego organization. But we do not yet understand this organization of the human being if we simply list these things in order, for each of these members is arranged in a different way in the universe. And only then, when we understand the classification of the various members in the universe, can we get an idea of man's position in the universe.

When we look at man as we have him before us, these four members of human nature are joined together in an initially indistinguishable way, united in an interaction, and in order to understand them, they must first be kept apart, so to speak, and each considered in its own particular relationship to the universe. We will be able to make such an observation, not in a comprehensive way, but from a certain point of view, if we do so in the following manner.

Let us turn our attention to the more peripheral aspects of man, to the external, to the perimeter. Here we first encounter the senses. We know, however, from other anthroposophical observations that we only discover certain senses when we go beneath the surface of the human form, so to speak, into the human interior. But essentially we would also have to look for the senses that inform us of our own inner being in a very unconscious way in their starting point, precisely on the inside of the surface of the human being. So that one can say that everything that is meaningful about man is to be sought on the surface. One need only look at one of the most conspicuous senses, for example the eye itself or the ear, and one will find that man must have certain impressions from outside. How they really behave, of course, must first be seen in a more detailed examination, in a more detailed research, which we have already carried out for some senses here in this room. But the way things present themselves in everyday life, we can say that a sense such as the eye or the ear perceives things through external impressions.

Now the position of man in earthly life is such that it is easy to see that the main direction in which the effects of things arrive, so that he comes to sensory perceptions, could be called approximately “horizontal”. A closer examination would also show that the assertion I have now made is entirely correct. For if it seems as if we were perceiving in a different direction, this is merely based on an illusion. Every direction of perception must ultimately fall into the horizontal. And the horizontal is the line that is parallel to the earth. So if I draw schematically, I would have to "say: If this is the surface of the earth and the perceiving person on it, then the main direction of his perception is this, which is parallel to the earth (drawing p. 42, left). The directions of all our perceptions run in this direction.

And if we look at the human being, we can easily say: Perceptions come from the outside, from the outside to the inside, so to speak. - What do we bring to them from the inside? We bring them thinking, the power of imagination, from within. You only need to visualize this process. You will say to yourself: When I perceive through the eye, the impression comes from the outside, the imagination comes from the inside (drawing p. 42, right). The impression comes from the outside when I see the table. The fact that I can then also keep the table in my memory with the help of an imagination is due to the power of imagination from within. So that we can say: If we imagine a person schematically, we have the direction of perception from the outside to the inside, the direction of imagination from the inside to the outside. What we have in mind here refers to the perceptions of the everyday life of the earthman, that earthman as he manifests himself outwardly in our present age of earthly development. It is what I have mentioned above, the facts of ordinary consciousness. But if you go through the anthroposophical literature, you will find that there are other possibilities of consciousness than those which are present for the earthling in everyday life.

Now try, even if only approximately and vaguely, to form a picture of what is perceived by the earthly human being. They see what is present on earth in colors, hear it in sounds, perceive it in sensations of warmth, and so on. You create contours for what is perceived, so that you perceive things in a structured way. But what we know ourselves to be in together with our surroundings is only the fact of ordinary everyday consciousness. There are other possibilities of consciousness which remain more unconscious in earthly man, which are pushed into the depths of the soul life, but which are of just as great, often much greater importance for this human life than those facts of consciousness which are exhausted in what I have mentioned so far.

For the human constitution, for what man is on earth, that which is within the surface of the earth is just as important as that which is in the circumference of the earth. The circumference of the earth, what is around the earth, that is what is perceptible to the ordinary senses, what can become the consciousness of the ordinary human being on earth through the power of imagination that meets sensory perception.

But let us first consider the interior of the earth. Ordinary reasoning will tell you that the interior of the earth is closed to ordinary consciousness. Certainly, we can dig a short distance into the earth and then observe in the holes, say in mines, just as we observe on the surface. But it is no different than when we observe the corpse of a human being. When we observe a corpse, we are only observing something that is actually no longer the whole human being, something that is a remnant of the whole human being; those who can look at these things correctly must even say: something that is the opposite of the human being. What is real about man on earth is man walking around alive, and that which he carries within him in terms of bones, muscles and so on is appropriate to him. The bone structure, muscle structure, nerve structure, heart, lungs and so on correspond to the living human being as a truth. When I have the corpse in front of me, it no longer corresponds to the human being. There is no reason for there to be a lung, a heart or a muscular system in the structure that I have before me as a corpse. That is why they disintegrate. For a while they retain the form that is imposed on them. But a corpse is actually an untruth, because it cannot exist as it is, it must disintegrate. It is not a reality. In the same way, what I find inside the earth when I dig into it is not a reality, because the closed earth has a different effect on the person standing on it than what the person, when he stands on the earth, sees as the surroundings of the earth through his senses. You can say, if you first look at the matter from a spiritual point of view: The surroundings of the earth are able to have an effect on man's ordinary senses and to be comprehended through the imaginative faculty of the ordinary earth-consciousness. What is inside the earth also has an effect on man, but it does not work in a horizontal direction, it works from the bottom up. It passes through the human being (drawing p. 46, left, red arrow). And during ordinary consciousness man does not perceive that which works from below upwards in the same way as he perceives that which is in his earthly surroundings through his ordinary senses. For if man were to perceive that which works upwards from the earth in the same way as he perceives that which is in his earthly surroundings, then he would have to have, as it were, a kind of eye or a kind of touch to reach into the earth without digging a hole in it, to reach through the earth just as one reaches through the air when one is attacking something, or as one looks through the air when one is looking at something. When you look through the air, you are not digging a hole through the air. If you were to dig a hole through the air and then look at it, you would look at the surroundings in the same way as you look at the earth in a mine. So if you did not need to dig a hole to see the inside of the earth, then you would have to have a sense organ that can see without digging holes in the earth, for which the earth, as it is, is transparent or perceptible. In a certain sense it is for man. But in ordinary earthly life man does not become aware of the perceptions in question. For what man would perceive there are the differentiated metals of the earth.

Just think how many metals the earth contains! Just as you perceive animals, plants, minerals, artifacts of various kinds in your air environment, so you perceive metals from within the earth. But the perceptions of metals, if they really came to your consciousness, would not be objective perceptions, they would be imaginations. And these imaginations are also constantly coming up from below into the human being. Just as the visual impressions come from the horizontal, so the metal irradiations continually come up from below, not the visual perceptions of the minerals, but something of the inner nature of the minerals works up through the human being into imaginations, into images. The human being does not perceive these images, but they weaken. They are suppressed, so to speak, because man's earthly consciousness is not such that he can perceive the imaginations. They weaken into feelings.

For example, if you think of all the gold that is in the earth . somehow in crevices and so on, your heart actually perceives an image that corresponds to the gold in the earth (drawing p. 46, left, purple). But this image is just imagination, and therefore it is not perceived by the ordinary consciousness, but is dulled to a mere inner feeling of life, a feeling of life which man cannot even interpret, let alone perceive the corresponding image. It is the same with other organs, for example, the liver perceives all the earth's tin in a certain image and so on.

These are all subconscious impressions, which only arise in a generally horizontal way, the perceptions come from the earth's surroundings and are met from within by the power of imagination, just as the metal perceptions, especially the metal perceptions, come from below and are met by feeling for the consciousness, just as the ordinary perceptions are met by the power of imagination (drawing on the left, yellow arrows). But for people living on earth today it remains chaotic and unclear. Only a general feeling of life emerges.

If this earthly man had a gift for imagination, he would know that his being is also connected with the metallic of the earth. Actually every human organ is a sense organ, and if we use it for something else, or if it appears that we use it for something else, it is still a sense organ. Its use in earthly life is actually only a vicarious one. With all the organs that man has, he actually perceives something. Man is completely and utterly a great sense organ, and again as such a great sense organ, differentiated into its individual organs as special sense organs.

The human being therefore has metal perceptions from below, and the emotional life corresponds to the metal perception. We have our feelings as a counter-effect to everything that has a metallic effect on us from the earth, just as we have our imagination as a counter-effect to everything that penetrates our sensory perception from our surroundings. But just as the human being has the metal effects from below, so that which is the movement and form of the heavenly bodies acts from above downwards from the world space. Just as we have sense perception in our surroundings, so we have inspiration from every planetary movement, from the constellation of the fixed stars, for a consciousness that would act as an inspired consciousness. And just as we let the power of imagination flow against the ordinary sense perceptions, so we let a force flow against the movements of the heavenly bodies (see drawing on the right, yellow arrows), which is opposed to the impressions of the stars, and this force is the power of will. What lies in our willpower, if we were to reckon with the inspired consciousness, we would perceive as inspiration.

When we study man in this way, then we say to ourselves: In his earthly consciousness we first find that in which he is most awake, the imaginative sensory life. Actually, we are only fully awake in this imaginative sensory life in ordinary earth consciousness. In contrast, our emotional life is only dreamlike. Our emotional life is no more intense, no brighter than dreams are, only dreams are images, while the emotional life is the general condition of the soul that can be determined by life, that of feeling. But this feeling is based on the metal effect of the earth. The consciousness of the will is even deeper - as I have often pointed out - and even duller. Man does not know what his will actually is within him. I have often expressed it in such a way that I said: Man has

the thought that he is stretching out his arm, that he is grasping something with his hand. He can have this thought with his waking consciousness. Then again he sees the fact of grasping. But what actually lies in between, this shooting of the will into the muscles and so on, remains just as hidden from ordinary consciousness as the experiences of deep dreamless

Sleep. In feeling we dream, in willing we sleep. But this will, which is asleep in ordinary consciousness, is precisely that which man responds to the impressions of the stars in exactly the same way as he responds to the sense impressions of ordinary consciousness in his ideas. And what man dreams in his feelings is the counter-effect to the metal effect of the earth.