Salt, Mercury, Sulphur

GA 220

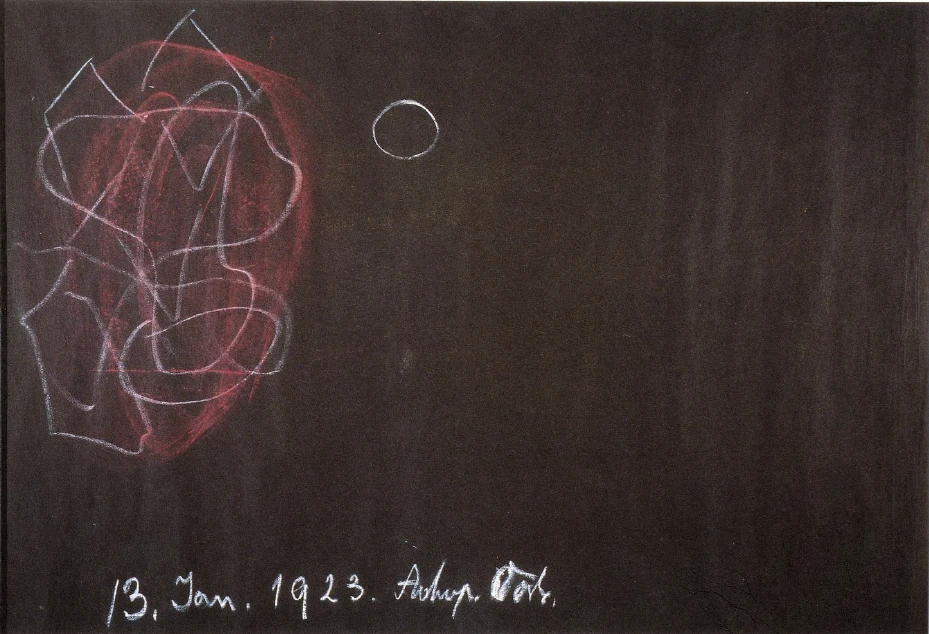

13 January 1923, Dornach

Edited by H. Collison

As I propose to follow up the theme of our lecture yesterday,1Published in Anthroposophy, Christmas, 1930. I would remind you of the three figures whose outstanding importance has lasted from the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries right on into our own times, namely, Giordano Bruno, Lord Bacon of Verulam and Jacob Boehme. We feel how they wrestled within themselves to understand man, to know something of the being of man, but yet were unable to attain their goal. In the time in which they lived, ancient knowledge of the being of man had been lost and the genuine strivings of the most eminent minds of the day were unable to lead to a new knowledge.

It was said that out of the strange and incoherent utterances of Jacob Boehme there resounds a kind of longing to know the universe in man and man in the universe. Out of the sum-total of his knowledge of the universe and of the being of man something glimmers which, to deeper insight, seems to point to man in pre-earthly existence, to man before he descends to earthly life. And yet we find in Jacob Boehme’s works no clear definition or description of man as a pre-earthly being.

I expressed this more or less as follows. I said that Jacob Boehme describes in halting words the being of pre-earthly man but the man he places before us would have had to die as a being of soul-and-spirit in the spiritual world before he could have come down to the earth. Jacob Boehme describes a rudiment only of pre-earthly man. And so he is incapable of understanding the reality of the universe in man and man in the universe.

If we then consider Giordano Bruno—semi-poet and semi-scientist—we find in him a knowledge of the universe which he expresses in pictures of great majesty. He too tries to fit man into his place within this majestic picture of the universe and he too is trying to recognise the universe in man and man in the universe. But he does not actually reach this knowledge. Giordano Bruno’s imagery is full of beauty and grandeur. On the one side it soars into infinitudes and on the other into depths of the human soul, but it all remains indefinite, even nebulous. Everything that Giordano Bruno says reveals a striving to describe the man of the present in the universe of space and the nature of the spatial universe itself.

And so while Jacob Boehme harks back ineffectually to pre-earthly man, Giordano Bruno gives us a blurred picture of man as he lives on earth in connection with space and with the cosmos too. The picture is not sufficiently clear to indicate real insight into that relation of man to the cosmos which would open up a vista of pre-earthly and post-earthly man.

If we then turn to Lord Bacon of Verulam, we find that he, in reality, no longer has any traditional ideas of the being of man. Of the old insight into human nature which had survived from ancient clairvoyant perception and from the Mysteries, there is no trace in him whatever.

Bacon, however, looks out into the world that is perceptible to the senses and assigns to human intelligence the task of combining the phenomena and objects of this world of sense-existence, of discovering the laws by which they are governed. He thus transfers the perception of the human soul into that world in which the soul is immersed during sleep, but there he only arrives at pictures of nature other than human nature. These pictures, if they are regarded as Bacon regarded them merely from the logical and abstract point of view, merely place the external aspect of human nature before us. If they are inwardly experienced, however, they gradually become vision of man’s existence after death, for a true clairvoyant perception of man’s being after death is to be obtained through this very medium of a real knowledge of nature. Thus Bacon too, at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is one of those who strive to recognise man in the universe and the universe in man.

But even his powers were inadequate for he did not intensify the pictures into a new experience. Indeed he could not do so, because the old reality was no longer living in the experiences of the soul. Bacon stands as it were at the threshold of the knowledge of life after death but does not actually attain to this knowledge.

We can therefore say: Jacob Boehme still shows signs of possessing a knowledge of pre-earthly man—a knowledge drawn from ancient tradition, but inadequate. Giordano Bruno embarks upon a description of the universe which might have led him to a knowledge of earthly man as he stands there with his life of soul on the one side and his cosmic background on the other. But Giordano Bruno fails to give an adequate description either of the cosmos or of the life of soul which, as presented by him, shrinks into an animated ‘monad.’

Bacon indicates the lines along which natural science must evolve, how it must seek with the powers of free human cognition for the spark of the Spiritual within the merely material. He points to this free activity of human knowledge, but it has no content. Had it been imbued with content Bacon would have been pointing to post-earthly man. But this he cannot do. His knowledge too remains inadequate.

All the living knowledge which in earlier epochs of human evolution it had been possible to create from the inner being, had by that time been lost. Man remained empty when he looked into his inner being with the object of finding knowledge of the universe. He had really ‘lost’ himself, together with his inner life of knowledge, and what remained to him was the vista of the outer world, of outer nature, of that which is not man. Jacob Boehme had gleaned from the Folk-Wisdom something like the following: In the human being there are three principles—salt, mercury, sulphur, as he calls them. These words have, however, an entirely different significance in his language from the significance attaching to them in modern chemistry. Indeed if we try to connect the conceptions of modern chemistry with Jacob Boehme’s magnificent, albeit stammering utterances, his words are entirely devoid of meaning. They were used, of course, by Boehme with a different meaning.

What did these expressions—salt, mercury, sulphur—still mean in the Folk-Wisdom from which Jacob Boehme derived his ideas? When Boehme spoke of the working of the salt, the mercury or the sulphur in man, he was speaking of something absolutely real and concrete. When man to-day speaks of himself, of his soul-nature, he gives voice to abstract ideas which have no real content. Jacob Boehme gathered together, as it were, the last vestiges of knowledge filled with concrete reality. Outer nature lay there perceptible to the senses, comprehensible to human reason. In this outer nature man learnt to see the existence of processes and phenomena and then in the succeeding centuries proceeded to build up an idea of the make-up of man from what he had been able to observe in nature. That is to say, understanding of the being of man was based on what was perceived to be outside man and in seeking thus to understand human nature by way of these external media, a conception of man's body too was built up without any knowledge as to whether this conception was in accordance with his true being or not.

By synthesising the processes which are to be observed in the outer, sense-perceptible world and applying them to the inner processes which take place within the limits of man’s skin, a kind of human spectre is evolved, never the real being of man. In this human spectre the faculties of thinking, feeling and willing also come into consideration, but they remain abstractions, shadowy thought-pictures filled with so-called inner experiences which are, in reality, mere reflections of processes in outer nature. At the time of Bacon there was no longer the slightest inkling of the way in which the being of spirit-and-soul penetrates into the bodily nature, and traditions which had been handed on from the old clairvoyant knowledge were not understood.

Now what has Spiritual Science to say to this? When in the first place we study the bodily nature of man, we have to do with processes connected with the senses, with nutrition, and also with those in which nutrition and sense-perception coincide. When man eats, he absorbs nutriment; he takes into himself the external substances of nature but at the same time he tastes them, so that a sense-perception is intermingled with a process which is continued from nature outside, on into man himself.

Think for a moment of the process of nutrition being accompanied by the perception of taste. We find that while the sense of taste is stimulated and the process of nutrition is set in operation, the outer substances are dissolved in the fluids and juices within the human organism. The outer substances which the plants absorb from lifeless nature are all, to begin with, given form. That which exists on earth without form, in lifeless nature, is really cloven asunder. Crystals are at the basis of all substances. And those substances which we do not find in crystallised form, but formless, in dust and the like, are really crystallisations which have been shattered. Out of crystallised, lifeless nature the plant draws its substances and builds them up into that form which is peculiar to its own nature. From this again the animal derives its nourishment. So that we may say: Out there in nature, everything has its form, its configuration. When man takes in these forms, he dissolves them. This is one form of the process which goes on in man’s organism. The forms, as they exist in outer nature, are dissolved. They are transmuted into the organic fluids.

But when the substances have been absorbed and transmuted into fluid, forms which were first dissolved begin to build up again. When we eat salt, it is first dissolved by means of the fluids in the organism, but we then give it form again. When we eat substances drawn from plants, they are dissolved and then inwardly reformed, not, this time, in the bodily fluids, but in the etheric body.

And now think of what happened in ancient times, when, for example, a man ate salt. It was dissolved and re-formed in his etheric body but he was able to perceive the whole process inwardly. He had an inner thought-experience of the formative process undergone by the salt. When he ate salt, the salt was dissolved and the salt-cube was there in his etheric body. From this he knew: salt has the shape of a cube. And so, as man experienced his being inwardly, he also experienced nature within himself. The cosmic thoughts became his thoughts. What he experienced as imaginations, as dreamlike imaginations, were forms which revealed themselves in his etheric body. They were cosmic forms, cosmic configurations.

But the age dawned when this faculty to experience in the etheric body these processes of dissolution and reconstruction was lost to man. He was obliged more and more to turn to external nature. It was no longer an inner experience to him that salt is cubic in form. He was obliged to investigate outer nature to find out the true configuration of salt.

In this way man’s attention was diverted entirely to the outer world. The radical change to this condition wherein men no longer experienced cosmic thoughts through inner perception of the etheric body, had been taking place since the beginning of the fifteenth century and had reached a certain climax at the time of Giordano Bruno, Jacob Boehme and Bacon of Verulam.

Jacob Boehme, however, had still been able to gather up those crumbs of Folk-Wisdom which told him: Man dissolves everything he assimilates from the outer world of matter. It is a process like salt being dissolved in water. Man bears this water within himself, in his vital fluids. All substances, in so far as they are foodstuffs, are salt. This salt dissolves. In the salts, the cosmic thoughts are expressed on earth. And man again gives form to these cosmic thoughts in his etheric body. This is the ‘salt-process.’

Jacob Boehme expressed in halting language that which in olden times was an inner experience. But if Anthroposophy did not shed light upon what Jacob Boehme says, we should never be able to interpret his stammering utterances. We should read into them all kinds of dark, mystical meanings. Jacob Boehme connected the thinking—the process by which the world presents itself to man in pictures—with the salt-process, that is to say, with the dissolving and re-forming process undergone by substance within the organism of man. Such was his ‘salt-process.’

It is often pathetic, although at the same time it shows up the conceit of some people, to see how they read Jacob Boehme and whenever they come across the word ‘salt,’ pretend to understand it, whereas in reality they understand nothing at all. They come along with their heads in the air saying that they have studied Jacob Boehme and find in him a profound wisdom. But there is no trace of this wisdom in the interpretations they bring forward. Were it not an evidence of conceit it would be quite pathetic to hear such people talk about matters of which Boehme himself had only a glimmering understanding from the Folk-Wisdom which he then voiced in halting words.

These things indicate the existence of an altogether different wisdom and science in olden times, a wisdom which was experienced through inner perception of the processes taking their course in the etheric body—processes which revealed themselves to man as the ever-recurring cosmic thoughts. The world constructed from the thoughts which are embodied in the crystal-formations of the earth, to which man gives form in his etheric body and consciously experiences - such was the ancient knowledge which disappeared in the course of time.

If we were able to transfer ourselves into one of the old Mystery-sanctuaries and listen spiritually to the description which an Initiate would give of the universe, it would have been something like the following: All through the universe the cosmic thoughts are weaving; the Logos is working. The crystal-formations of the earth are the embodiments of the single parts of the cosmic Word. Now the sense of taste is only one of the many senses. The processes of hearing and of sight can be dealt with in a similar way though in their case the working of the salts in etheric form must be thought of in a more outward sense. Man receives through his senses that which is embodied in the salts and re-forms it in his etheric body, experiences it within himself. Cosmic thoughts repeat themselves in the thoughts of men. The universe is recognised in man and man in the universe. With concrete and unerring intuition the Initiates of olden times were able to describe this out of their visionary, dream-like knowledge of the universe and of man.

During the course of the Middle Ages this wisdom was gradually superseded by a merely logical form of knowledge which, though of great significance, became, nevertheless, entirely academic and on the other side had trickled away into Folk-Wisdom. What was once sublime wisdom, relating both to the cosmos and to man had degenerated into sayings used by simple folk who by that time understood little of their meaning but who still felt that some great value was contained in them. It was among such people that Jacob Boehme lived. He absorbed this Folk-Wisdom and by his own genius revived it within him. He was more articulate than those among whom he lived but even he could do no more than express it in halting language.

In Giordano Bruno there was a feeling that man must learn to understand the universe, must get to know his own nature, but his faculties did not enable him to say anything so definite as: ‘Out there are the cosmic thoughts, a universal Word which enshrines itself in the crystal; man takes into himself these cosmic thoughts when, knowingly and deliberately, he dissolves the salts and gives them new form in his etheric body.’ It is so, indeed: from the concrete thoughts of the world of myriad forms, from the innermost thoughts of man, there arises an etheric world as rich in its varied forms as the world outside us.

Just think of it: This wealth of thought in regard to the cosmos and to man shrinks, in Giordano Bruno, into generalisations about the cosmos. It hovers into infinitudes but is nevertheless abstract. And that which lives in man as the world re-formed, shrinks into a picture of the animate monad—in reality, nothing but an extended point.

What I have described to you was real knowledge among the sages of old; it was their science. But in addition to the fact that these ancient sages of the Mysteries were able, by their own dream-veiled vision, to evolve this knowledge, they were able to have actual intercourse with the spiritual Beings of the cosmos. Just as here on earth a man enters into conscious relationship with other human beings, so did these ancient sages enter into relation with spiritual Beings. And from these spiritual Beings they learned something else, namely that what man has formed in his etheric body—by virtue of which he is inwardly another cosmos, a microcosm, an etheric rebirth of the macrocosm—what he thus possesses as an inner cosmos, he can in the element of air, by the process of breathing, again gradually obliterate.

And so in those ancient times man knew that within him the universe is reborn in varied forms; he experienced an inner world. Out of his inner vital fluids the whole universe arose as an etheric structure. That was ancient clairvoyance. Man experienced a real process, an actual happening. And in modern man the process is there just the same, only he cannot inwardly experience it.

Now those spiritual Beings with whom the ancient sages could have real intercourse did not enlighten them only in regard to the vital fluids from which this micro-cosmic universe was born but also in regard to the life-giving air, to the air which man takes in with his breath and which then spreads through his whole organism. This air which spreads itself over the whole of the microcosm, renders the shapes therein indistinct. The wonderful etheric universe in miniature begins, directly the breath contacts it, to become indefinite, That which formerly consisted of a myriad forms, is unified, because the ‘astral’ man lives in the airy element, just as the etheric man lives in the fluids. The astral being of man lives in this airy element and by the breaking up of the etheric thoughts, by the metamorphosis of etheric thoughts into a force, the will is born from the working of the ‘astral man’ in the ‘air man.’ And together with the will there arise the forces of growth which are connected with the will.

This knowledge again expressed a great deal more than is suggested nowadays by the abstract word ‘will.’ It is a concrete process. The astral lays hold of the airy element and spreads over that which is etheric and fluidic. And thereby a real process is set up which appears in outer nature at a different stage, when something is burnt. This process was conceived by the ancients as the sulphur-process. And from the sulphur-process there unfolded that which was then experienced in the soul as will.

In olden times men did not use the abstract word think to express something that arose in the mind as a picture. When a real knower spoke about ‘thinking’ he spoke of the salt-process just described. Nor did he speak in an abstract way of the ‘will’ but of the astral forces laying hold of the airy element in man, of the sulphur-process from which the will is born. Willing was a process of concrete reality and it was said that the adjustment between the two—for they are opposite processes—was brought about by the mercury-process, by that which is fluid and yet has form, which swings to and fro from the etheric nature to the astral nature, from the fluidic to the aeriform. The abstract ideas which were gradually evolved by Scholasticism and have since been adopted by modern science, did not exist for the thinkers of olden times. If they had been confronted with our concepts of thinking, feeling and willing they would have felt rather like frogs in a vessel from which all the air has been pumped. This is how our abstract concepts would have appeared to the thinkers of old. They would, have said: It is not possible for the soul to live or breathe with concepts like this. For the thinkers of old never spoke of a purely abstract will-process, of a purely abstract thought-process, but of a salt-process, of a sulphur-process, and they meant thereby, something that on the one hand is of the nature of soul-and-spirit and on the other of a material-etheric nature. To them, this was a unity and they perceived how the soul works everywhere in the bodily organism.

The writings of the Middle Ages which date back to the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries still showed traces of this ancient faculty of perception and of a knowledge that was at the same time inner experience. This kind of knowledge had faded away at the time of Giordano Bruno, Jacob Boehme and Bacon of Verulam. Ideas had become abstract; man was obliged to look, not into his own being but out into nature. I have told you that our concepts to-day would have made the wise men of old feel like frogs exhausted by lack of air. We, however, find it possible to exist with such ideas. The majority of people when they speak of thinking, feeling and willing, consider them at most mirror-pictures of external nature which appear in man. But precisely in our age it is possible to attain to what in olden times was not possible. Man lost the spontaneous, inner activity which gives birth to knowledge. In the interval which has elapsed since the fifteenth century, man has lost the capacity to discover anything when he merely looks into his inner being. He therefore looks out into nature and evolves his abstract concepts. None the less it is possible so to intensify these concepts that they can again be filled with content because they can be experienced. We are, of course, only at the very beginning of this phase of development, and anthroposophical Spiritual Science tries to be such a beginning.

All the processes I have described above—the salt process, the sulphur-process—are nowhere to be found in this form in external nature; they are processes which can only be known by man as taking place in his image being. In outer nature there transpires something which is related to these processes as the processes in a corpse are related to those in a living man. The salt- and sulphur-processes spoken of by modern chemistry are those which the old Folk-Wisdom living in Jacob Boehm conceived as taking place within a corpse. Such processes are dead, whereas they were once filled with inner life. And as he observed them in their living state, man saw a new world—a world which is not the world surrounding him on earth.

The ancients, then, were able with the help of their inwardly experienced knowledge, to see that which is not of the earth, which belongs to a different world. The moment we really understand these salt-and sulphur-processes we see the pre-earthly life of man. For earthly life differs from the pre-earthly life precisely in this: the sulphur- and salt-processes are dead in the external world of sense; in pre-earthly existence they are living. What we perceive with our senses between birth and death, is dead. The real salt- and sulphur-processes are living when we experience them as they are in pre-earthly existence. In other words, understanding of these processes of which Jacob Boehme speaks in halting words, is a vision of pre-earthly existence. That Jacob Boehme does not speak of pre-earthly existence is due to the fact that he did not really understand it and could only express it in faltering words.

This faculty of man to look back into pre-earthly existence has been lost—lost together with that union with the spiritual Beings who help us to see in the sulphur-process the reality of post-earthly existence. The whole attitude of the human soul has entirely changed. And Giordano Bruno, Jacob Boehme and Lord Bacon of Verulam lived precisely at the time of this change.

In the last lecture I drew your attention to the fact that of the way man felt himself placed in the universe in earlier times not the faintest notion remains to-day. Consequently no great importance is attached to information which dates back beyond comparatively recent times.

Here in Dornach we have given many performances of the play of the Three Kings. This story of the visit of the Three Kings to the Child Jesus is also given in the old German song of the “Heliand.” You are aware that it dates back to a comparatively early period of the Middle Ages and that it originated in Central Europe. There is something remarkable here. It is obvious that something else is connected with this visit of the Three Kings from the East. These Kings relate that they have come from regions where conditions were very different from what they now find (i.e., at the beginning of our era). They tell us that they are the descendants of ancestors who were possessed of a wisdom incomparably greater than any contemporary wisdom. They speak of an ancestor far back in time—an ancestor who was able to hold converse with his God. And when he came to die, this ancestor assembled all his family and told them of what his God had revealed to him, namely, that in the course of time a World-King would appear whose coming would be heralded by a star.

When search is made for an indication of this ancestor, we find—and even literature points to this—that he is Balaam, mentioned in the fourth book of Moses in the Old Testament. These three Holy Kings from the East, therefore, are referring to Balaam, the son of Beor, of whom it is related in the fourth Book of Moses that he held converse with his God and that he regulated his whole earthly life in accordance with that converse.

In short, when we examine the facts, they tell us that at the time when this old German poem originated, a consciousness still existed of ages when men had intercourse with the Gods. A very real conception of this still remained, with men. Again here, we have an indication of something which the contemplation of history revealed to these people and which proves to us that we have passed from those olden times when men felt themselves placed in a living universe, into a Philistine age. For our civilisation is really a Philistine civilisation. Even those who believe that they have grown out of it are by no means so opposed to Philistinism that they would find it possible to accept such traditions as that of Balaam being the ancestor of the Three Kings. Such people have by no means grown beyond Philistinism. The most that could be said of them is that they are ‘Bohemians!’

These things indicate what a mighty change has taken place in the attitude of the human soul. Centuries ago it was known that with their dreamy clairvoyant faculties men were able to observe the actual working of such processes as the sulphur-process and the salt-process. And because of this they were able to see into the pre-earthly state of existence.

Certain people who did not desire the upward progress, but rather the retrogression of humanity, but who were nevertheless initiated in a certain sense, saw in advance that human beings would lose this capacity; that a time would come when nothing would be known any longer about pre-existence. And so they laid it down as a dogma that there is no pre-existent life, that man’s soul is created together with his physical body. The fact of pre-existence was shrouded in the darkness of dogma. That was the first step downwards of what had once been knowledge of man’s place in the universe. It was a step downwards into ignorance for it is not possible to understand man if one part of his existence is obliterated, especially so important a part as his pre-existent life.

Now Jacob Boehme, Giordano Bruno and Lord Bacon of Verulam lived at a time when this insight into pre-existent life had faded away. And moreover the age had not yet dawned when the inner experiencing of knowledge was to give place to a spiritual perception of external nature, whereby man, who can no longer find himself in his inner being, finds himself again in nature outside. For a long time there had been Initiates who wished to lead mankind on the downward path. Such Initiates did not desire that the new faculty of insight—which was exactly the reverse of the old clairvoyance—should make headway. And they tried by means of dogma to replace the new form of knowledge by mere faith and belief in the life after death. And so, in Giordano Bruno's time, dogmatic decrees had wiped out the possibility of knowledge of pre-existent life and of life after death. Giordano Bruno stood there wrestling—wrestling more forcibly than Jacob Boehme and much more forcibly than Lord Bacon. Giordano Bruno stood there among the men of his time, unable to transmute the Dominican wisdom that lived in him into a true conception of the universe. And he expressed in poetic language the somewhat indefinite views which he was able to evolve.

But the knowledge which Giordano Bruno possessed in so nebulous a form must give birth to a definite and precise understanding of man in the universe and the universe in man, not by means of a recrudescence of inner clairvoyance but by means of new clairvoyant faculties acquired by free spiritual activity.

With these words I have indicated what must take place in the evolution of mankind. And in our day humanity is faced with the fact that the will to attain this higher knowledge is violently opposed and hated by numbers of people. This too is apparent in events of which history tells. And when we understand these events we also understand why it is that bitter opposition arises to anthroposophical conceptions of the world.

Fünfter Vortrag

Indem ich die gestrigen Betrachtungen fortsetzen will, möchte ich nur daran erinnern, daß die drei Gestalten, deren Bedeutung zu uns herüberragt aus der Wende des 16. zum 17. Jahrhundert, und die ich zu charakterisieren versuchte, Giordano Bruno, Baco von Verulam und Jakob Böhme, uns alle darauf hinweisen, wie in ihnen ein Ringen lebte, den Menschen zu verstehen, etwas zu wissen über das Wesen des Menschen selbst, und wie zu gleicher Zeit in diesen drei Gestalten eine gewisse Unfähigkeit lebte, zu einem solchen Erkennen des Menschen zu kommen. Das ist das Charakteristische, daß man deutlich sieht in dieser Zeitepoche, auf die ich hinwies, wie eine alte Menschenerkenntnis verlorengegangen ist und wie das ehrlichste, aufrichtigste Ringen der hervorragendsten Geister zu einer neuen Menschenerkenntnis nicht führt.

Wir mußten ja darauf hinweisen, daß aus der eigentümlich stammelnden Sprache des Jakob Böhme heraus etwas tönt wie die Sehnsucht, die Welt im Menschen, den Menschen in der Welt zu erkennen, wie aber aus allem, was Jakob Böhme zu einer solchen Welt- und Menschenerkenntnis zusammenbringt, etwas herausleuchtet, was sich vor der gegenwärtigen anthroposophischen Anschauung wie ein Hinweis auf das Wesen des vorirdischen Menschen darstellt, des Menschen, bevor er zum irdischen Dasein heruntergestiegen ist, und daß doch wiederum bei Jakob Böhme eine klare Darstellung dieses Wesens nicht zu finden ist. Ich sprach das etwa mit diesen Worten aus: Jakob Böhme schildert in stammelnden Worten das Wesen des vorirdischen Menschen, aber so, daß der Mensch, den er da schildert, eigentlich als geistig-seelisches Wesen in der geistigen Welt sterben mußte, bevor er auf die Erde heruntersteigen konnte. Ein Rudiment gewissermaßen des vorirdischen Menschen schildert Jakob Böhme. Also es ist bei ihm das Unvermögen vorhanden, die Welt im Menschen, den Menschen in der Welt wirklich zu verstehen.

Sehen wir dann auf den poetisierenden Giordano Bruno, so finden wir eine in Bildern dargestellte Welterkenntnis grandioser Art. Wir finden auch den Versuch, den Menschen hineinzustellen in dieses grandiose Weltenbild, also wiederum den Versuch, die Welt im Menschen, den Menschen in der Welt zu erkennen. Aber es kommt nicht zu einer solchen Erkenntnis. Giordano Brunos mächtige Bilder sind schön und grandios, sie schweifen in Unendlichkeiten auf der einen Seite, und in Tiefen der menschlichen Seele auf der andern Seite. Aber sie bleiben unbestimmt, sie bleiben sogar verschwommen. Nach allem, was Giordano Bruno spricht, finden wir bei ihm ein Streben, den gegenwärtigen Menschen im räumlichen Weltenall und das räumliche Weltenall selbst darzustellen.

Während also Jakob Böhme auf den vorirdischen Menschen in ungenügender Art hinweist, sehen wir bei Giordano Bruno eine verschwommene Darstellung des Menschen, wie er auf Erden lebt, im Zusammenhange mit dem räumlichen, also auch für den irdischen Menschen bestehenden Kosmos, aber eben ungenügend. Denn eine wirklich genügend durchgreifende Anschauung des Verhältnisses des Menschen zum Kosmos für die Gegenwart gibt einen Ausblick auf den vorirdischen Menschen und einen Ausblick auf den nachirdischen Menschen, wie ich das vor einer kurzen Zeit hier am Goetheanum in dem sogenannten Französischen Kurs dargestellt habe.

Und sehen wir wiederum auf Baco von Verulam, Lord Bacon, dann finden wir, daß er eigentlich keine traditionellen Vorstellungen vom Menschen mehr hat. Von den alten Einblicken in die menschliche Natur, welche herübergekommen waren aus alten hellseherischen Anschauungen, und von den alten Mysterienwahrheiten, findet sich ja nichts bei Baco von Verulam. Aber Baco von Verulam wendet den Blick hinaus in die Welt, die für die Sinne wahrnehmbar ist, und teilt dem menschlichen Verstande die Mission zu, die Erscheinungen und die Dinge dieser Welt des Sinnendaseins zu kombinieren, Gesetze zu finden und so weiter. Er versetzt also die Anschauung der menschlichen Seele in diejenige Welt, in welcher der Mensch als Seele ist vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen, aber er gelangt da nur zu Bildern von der nichtmenschlichen Natur. Diese Bilder, wenn sie bloß, wie sie Lord Bacon nimmt, logisch und abstrakt genommen werden, stellen nur die äußere menschliche Natur dar. Wenn sie erlebt werden, dann werden sie allmählich zu etwas, was den Ausblick gibt auf des Menschen Dasein nach dem Tode. Denn gerade aus einer wirklichen Naturerkenntnis heraus kann eine exakt clairvoyante Anschauung über das Wesen des Menschen nach dem Tode gewonnen werden. So ist auch Bacon einer, der ringt nach jener Erkenntnis des Menschen in der Welt, der Welt im Menschen, um die Wende des 16. zum 17. Jahrhundert. Aber auch seine Kräfte bleiben ungenügend, denn dasjenige, was im bloßen Bilde auftritt, weil eine alte Realität im seelischen Erleben nicht mehr vorhanden ist, das intensivierte er nicht zu einem neuen Erleben. Er steht gewissermaßen vor der Pforte zur Erkenntnis des Lebens nach dem Tode, gelangt aber nicht an diese Erkenntnis heran.

So daß wir sagen können: Jakob Böhme gibt noch eine Erkenntnis in alten Traditionen über den vorirdischen Menschen, die aber ungenügend ist. Giordano Bruno steht vor einer Weltenschilderung, die ihm den gegenwärtigen Menschen geben könnte, den irdischen Menschen mit seinem Seelischen auf der einen Seite, mit seinem Hintergrunde des Kosmos auf der andern Seite. Allein, Giordano Bruno bleibt bei einer ungenügenden Schilderung des Kosmos und bei einer ebenso ungenügenden Schilderung des seelischen Lebens, das bei ihm zu einer bloßen belebten Monade zusammenschrumpft.

Lord Bacon zeigt bereits, wie Naturwissenschaft sich entwickeln muß, wie Naturwissenschaft aus der bloßen Materie heraus den Funken des Geistigen in freier menschlicher Erkenntnis suchen muß. Er deutet hin auf diese freie menschliche Erkenntnis, aber sie bekommt keinen Inhalt. Würde sie Inhalt bekommen, so müßte er hindeuten auf den nachirdischen Menschen. Das kann er nicht. Auch seine Erkenntnisfähigkeit bleibt unvermögend.

All das, was in früheren Epochen der irdischen Menschheitsentwickelung an lebendiger Erkenntnis aus dem Innern hat geschöpft werden können, das war in jener Zeit vergangen. Der Mensch war gewissermaßen dazu gelangt, leer zu bleiben, wenn er in sein Inneres blickte und aus seinem Inneren Erkenntnis über die Welt gewinnen wollte. Der Mensch hatte, man darf schon sagen, in einer gewissen Weise sich selbst verloren, sich verloren mit dem inneren Erkenntnisleben. Und geblieben war ihm der Ausblick auf die äußere Welt, auf die äußere Natur, auf das, was nicht Mensch ist.

Jakob Böhme hatte, wie ich gestern schon andeutete, aus der Volksweisheit heraus noch so etwas genommen wie dieses: In der menschlichen Wesenheit leben drei Prinzipien, die er Salz, Merkur, Sulfur nannte. Diese Worte bedeuten noch in seiner Sprache etwas ganz anderes als in unserer heutigen chemischen Sprache. Denn verbindet man die Begriffe, die heute in der Chemie üblich sind, mit dem, was Jakob Böhme in großartiger Weise stammelt, so hat dieses Jakob Böhmesche Stammeln überhaupt keinen Sinn mehr. Die Worte wurden für anderes gebraucht. Und wofür wurden sie gebraucht? Worauf deutete selbst noch ihr Gebrauch in der Volksweisheit hin, aus der Jakob Böhme geschöpft hat? Ja, indem Jakob Böhme von einem Wirken des Salzigen, des Merkurischen, des Sulfurigen im Menschen sprach, sprach er von etwas Konkretem, von Realem.

Wenn der Mensch heute von sich selber spricht, spricht er von dem Seelischen ganz in Abstraktionen, für die er keinen Inhalt mehr bekommt; die Realität, die Wirklichkeit war aus dem menschlichen Begriff hinweggegangen. Die letzten Brocken sozusagen sammelt Jakob Böhme noch auf. Die äußere Natur lag, für die Sinne wahrnehmbar, für den Verstand zu kombinieren, vor dem Menschen ausgebreitet. Aber in dieser äußeren Natur lernte man Vorgänge, lernte man Dinge kennen, und dann baute man in den folgenden Jahrhunderten bis heute auch den Menschen auf aus demjenigen, was man in der Natur hat erkennen können. Man mußte sozusagen den Menschen durch das Aufßermenschliche begreifen. Und indem man den Menschen durch dieses Außermenschliche zu begreifen suchte, baute man, ohne daß) man es wußte, ob das auch mit der menschlichen Wesenheit wirklich stimmt, seinen Körper auf.

Man bekommt in einer gewissen Weise eine Art Aufbau eines Menschengespenstes dadurch, daß man für die Vorgänge innerhalb der menschlichen Haut jene Vorgänge kombiniert, die man draußen in der sinnlichen Natur beobachtet. Aber auf diese Weise kommt man nicht mehr an den Menschen heran. Spricht man dann über den Menschen, so redet man wohl von Denken, Fühlen, Wollen, aber das bleiben Abstraktionen, das bleiben schattenhafte Gedankenbilder, von sogenannten inneren Erlebnissen ausgefüllt. Denn diese inneren Erlebnisse sind ja nur die Spiegelungen der äußeren Natur. Wie das Geistig-Seelische eingreift in die menschliche körperliche Wesenheit, davon hatte man eigentlich keine Ahnung mehr. Und was traditionell überliefert war aus alter hellseherischer Erkenntnis, das verstand man nicht mehr.

Was hat dazu unsere heutige anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft zu sagen? Erinnern Sie sich an manches, was darüber gesagt worden ist. Wir haben es zu tun im Menschen, wenn wir zunächst auf sein Körperliches hinschauen, mit solchen Vorgängen, die sich abspielen in Anlehnung an die Sinne. Wir haben es zu tun mit Vorgängen, die sich abspielen in Anlehnung an die Ernährung des Menschen. Und wir sehen auch solche Vorgänge, wo gewissermaßen die Ernährung mit der Sinneswahrnehmung zusammenfällt. Wenn der Mensch ißt, so nimmt er die Nahrungsmittel in sich auf. Die äußeren Stoffe der Natur also nimmt er in sich auf. Aber er schmeckt sie zugleich. Also eine Sinneswahrnehmung vermischt sich mit einem Vorgang, der von der äußeren Natur in den Menschen herein geschieht.

Greifen wir einmal gerade diesen Vorgang heraus, daß in Begleitung der Geschmackswahrnehmungen sich die Ernährung vollzieht. Da finden wir zunächst, daß, während sich die Geschmackswahrnehmung abspielt und der Ernährungsvorgang eingeleitet wird, die äußeren Stoffe aufgelöst werden in den Säften, die im menschlichen Organismus enthalten sind. Die außeren Stoffe, welche die Pflanze aufnimmt aus der leblosen Natur, sind eigentlich, zunächst in ihren Prinzipien, alle gestaltet. Dasjenige auf der Erde, was nicht gestaltet ist in der leblosen Natur, ist eigentlich zerklüftet. Wir müssen eigentlich für alle Stoffe Kristalle suchen. Und diejenigen Stoffe, die wir nicht in kristallisierter Form, die wir gestaltenlos oder als Staub und dergleichen finden, die sind eigentlich zerstörte Kristallisationen. Und aus der kristallisierten leblosen Natur entnimmt die Pflanze ihre Stoffe und baut sie eben in der Form auf, welche die Pflanze haben kann. Daraus wiederum nimmt das Tier die Stoffe und so weiter. So daß wir sagen können: Draußen in der Natur hat alles seine Form, hat alles seine Gestaltungen. Indem der Mensch diese Gestaltungen aufnimmt, löst er sie auf. — Darin besteht die eine Form der Vorgänge, welche sich im Menschen vollzieht: im Auflösen der gestalteten äußeren Natur. Das alles geht gewissermaßen in das Wässerige, in das Flüssige über.

Aber indem das nun in das Wässerige, in das Flüssige übergeht, wenn der Mensch es aufnimmt, bildet er innerlich diese Gestalten wiederum aus dem, was er erst aufgelöst hat. Er schafft diese Gestalten. Wenn wir Salz zu uns nehmen, lösen wir es auf durch das Flüssige unseres Organismus, aber wir gestalten in uns dasjenige, was das Salz war. Wenn wir eine Pflanze aufnehmen, so lösen wir die Stoffe der Pflanze auf, aber wir gestalten innerlich wiederum. Aber wir gestalten das jetzt nicht im Flüssigen, wir gestalten es im Ätherleib des Menschen.

Nun ist das Folgende der Fall: Wenn Sie sich zurückversetzen in alte Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung, da nahm der Mensch zum Beispiel Salz zu sich. Er löste es auf, das Aufgelöste gestaltete er in seinem Ätherleib wiederum. Er konnte aber innerlich diesen ganzen Prozeß wahrnehmen, das heißt, er konnte aus sich heraus den Gedanken an die Salzgestalt erleben. Der Mensch aß Salz, er löste das Salz auf, in seinem Ätherleib war der Salzwürfel, und er wußte daraus: das Salz hat die Gestalt des Würfels. Und so erlebte der Mensch, indem er innerlich sich erlebte, eben auch die Natur innerlich. Die Weltengedanken wurden seine Gedanken. Das, was er als Imagination erlebte, als traumhafte Imagination, waren im Menschen sich darstellende, ätherisch sich bildende Gestaltungen, die aber die Gestaltungen der Welt waren.

Jetzt war die Zeit heraufgezogen, durch welche dem Menschen diese Fähigkeit abhanden gekommen war, innerlich seinen Auflösungsprozeß und Wiedergestaltungsprozeß im Ätherischen zu erleben, und er wurde immer mehr und mehr angewiesen, die Frage an die äußere Natur zu stellen. Er konnte nicht mehr innerlich durch Anschauen erleben, daß das Salz in Würfelform gestaltet ist. Er mußte in der äußeren Natur nachforschen, welches die Gestalt des Salzes ist. So wurde der Mensch von innen abgelenkt und auf das Äußere gelenkt. Der radikale Umschwung zu diesem Zustande, daß der Mensch innerlich die Weltengedanken nicht mehr in Selbstwahrnehmung seines Ätherleibes erlebte, der vollzog sich eben seit dem Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts, und war zum Beispiel bis zu einer gewissen Höhe gestiegen in der Zeit, in der Giordano Bruno, Jakob Böhme und Baco von Verulam lebten.

Jakob Böhme hatte aber noch eben die Brocken der Volksweisheit aufgenommen, die eigentlich so zu ihm gesprochen hat: Der Mensch löst alles, was er an äußeren Stoffen einnimmt, auf. Es ist ein Prozeß, so wie wenn man Salz in Wasser auflöst. Der Mensch tragt dieses Wasser in seiner Lebensflüssigkeit in sich. Alle Stoffe sind, insofern sie Nährstoffe sind, Salz. Das löst sich auf. Im Salz, in den Salzen sind die Weltengedanken auf der Erde ausgedrückt. Und der Mensch gestaltet wiederum diese Weltengedanken in seinem ätherischen Leibe. Das ist der Salzprozeß. So sprach Jakob Böhme stammelnd dasjenige aus, was in alten Zeiten eben durch innerliches Erleben noch erkannt worden war. Aber wenn man nicht mit den Mitteln der Anthroposophie hineinleuchtet in das, was Jakob Böhme sagt, so wird man die stammelnden Sätze doch nicht in der richtigen Weise entziffern können und allerlei mystisch-nebuloses Zeug hinein interpretieren. So daß man also besser sagen kann: Jakob Böhme brachte den Denkprozeß, den Vorgang, durch den man die Welt vorstellt in Bildern, mit dem Salzprozeß, mit dem Auflösungsprozesse und dem Wiedergestaltungsprozesse des Aufgelösten zusammen. Das war sein Salzprozeß.

Es ist manchmal, wenn es nicht zu gleicher Zeit eben den Hochmut vieler Leute verriete, rührend zu sehen, wie sie Jakob Böhme lesen und da, wo bei ihm das Wort Salz steht, irgend etwas zu verstehen glauben, während sie gar nichts verstehen. Dann kommen sie, halten den Kopf hoch, die Nase in die Lüfte und sagen, sie haben Jakob Böhme gelesen und das ist ungeheuer tiefe Weisheit. Aber diese Weisheit lebt nicht in den Interpreten, in denen, die solche Behauptungen aufstellen. Wenn es nicht hochmütig wäre, wäre es sogar rührend, wie die Leute über dasjenige sprechen, was Jakob Böhme selber nur noch annähernd verstanden hat, indem er die Volksweisheit aufgenommen und in stammelnde Sätze gebracht hat.

Aber damit ist uns ja hingedeutet auf eine ganz andersgeartete Weisheit und Wissenschaft der alten Zeiten, auf eine Weisheit, die erlebt wurde, indem der Mensch die Selbstwahrnehmung der Vorgänge in seinem Ätherleib hatte, die sich ihm darstellten als die in ihm sich wiederholenden' Weltengedanken. Die Welt, aufgebaut nach den Gedanken, die wir verkörpert sehen in den Kristallisationen der Erde, die der Mensch wiederum gestaltet in seinem Ätherleib und erkennend miterlebt: das war jenes alte Erkennen, das verschwunden war in einer gewissen Zeit.

Versetzt man sich in ein altes Mysterium und lauscht der Schilderung, die ein solcher Mysterieneingeweihter vom Weltenall gegeben hat, dann wird einem so etwas geistig-seelisch hörbar - wie die Worte, die ich eben ausgesprochen habe: Überall im Weltenall wirken die Weltengedanken, wirkt der Logos. Schauet auf die Kristallisationen der Erde! In ihnen sind Verkörperungen der einzelnen Worte des universellen Logos.

Der Geschmackssinn ist nur einer von den vielen Sinnen. Dasjenige, was der Mensch hört und was der Mensch sieht, ist in einer ähnlichen Weise zu behandeln, wenn auch da das Salz in einer mehr ätherischen Form schon äußerlich aufgefaßt werden muß. Aber der Mensch nimmt durch seine Sinne das, was in den Salzen verkörpert ist, auf und gestaltet es wieder in seinem Ätherleib, erlebt es in sich. Die Weltengedanken wiederholen sich in den Menschheitsgedanken, man erkennt die Welt im Menschen, den Menschen in der Welt. Mit einer ungeheuren Anschaulichkeit, mit einer konkreten Intensivität schilderten das aus ihren traumhaft-visionären Weltenerkenntnissen und Menschenerkenntnissen heraus die alten Eingeweihten.

Das war im Verlaufe des Mittelalters allmählich verschwunden hinter einer bloß logischen Weisheit, die allerdings sehr bedeutend, aber eben eine bloß scholastische Weisheit gewesen ist, und es war hinuntergesickert und Volksweisheit geworden. Man möchte sagen, was einstmals eine hohe kosmische und humanistische Weisheit war, war übergegangen in die Volksaussprüche, die von Leuten getan wurden, die wenig mehr davon verstanden, die aber noch fühlten, daß ihnen da ein ungeheures Gut erhalten geblieben war. Und unter solchen Leuten lebte Jakob Böhme, nahm die Dinge auf, und durch sein eigenes Talent belebten sie sich in ihm, und er konnte mehr sagen als das Volk. Aber er konnte eben auch nur zum Stammeln kommen.

In Giordano Bruno lebte nichts mehr als das allgemeine Gefühl: Man muß den Kosmos erkennen, man muß den Menschen erkennen. Aber es reichte seine Erkenntnisfähigkeit nicht aus, so etwas Konkretes zu sagen wie: Weltengedanken sind draußen, ein Weltenlogos, der sich in den Kristallen verkörpert. Der Mensch nimmt die Weltengedanken auf, indem er wahrnehmend und sich erahnend auflöst das Salzige und es wiedererstehen läßt in seinem Ätherleib, wo er ihn erlebt, den konkreten Gedanken von der vielgestaltigen Welt, und jenen konkreten Gedanken von dem menschlichen Innern, aus dem aufsprießt, ätherisch ebenso reich sich gestaltend eine Welt - wie es die Welt draußen ist. Denken Sie sich diese unendlich reichen Gedanken! Der kosmische Gedanke und der menschliche Gedanke, sie schmolzen sozusagen zusammen bei Giordano Bruno zu einer allgemeinen Schilderung des Kosmos, die allerdings, wie ich sagte, in Unendlichkeiten schweifte, aber abstrakt war. Und was im Menschen lebt als die wiedergestaltete Welt, das schmolz zusammen zu der Schilderung der lebendigen Monade: im Grunde genommen ein ausgedehnter Punkt, weiter nichts.

Dieses, was ich Ihnen geschildert habe, war in einem gewissen Sinne Einsicht der alten Mysterienweisen. Es war ihre Wissenschaft. Aber außer dem, daß die alten Mysterienweisen durch ihre besondere, in Traum gehüllte Methode eine solche Wissenschaft erringen konnten, hatten sie ja auch noch die Möglichkeit, mit geistigen Wesenheiten des Kosmos in wirkliche Verbindung zu treten. So wie hier auf Erden ein Mensch mit dem andern in bewußte Verbindung tritt, so traten diese alten Weisen in Verbindung mit geistigen Wesenheiten des Kosmos. Und von diesen geistigen Wesenheiten lernten sie nun den andern Teil, den man bei ihnen findet: Sie lernten von diesen geistigen Wesenheiten, daß nur der Mensch dasjenige, was er so im Ätherleibe gestaltet, wodurch er eigentlich innerlich eine Wiederholung des Kosmos ist — ein kleiner Kosmos, ein Mikrokosmos, eine ätherische Wiedergeburt des großen, des Makrokosmos —, daß er, was er auf diese Weise als innerlichen Kosmos hat, in dem Elemente der Luft durch den Atmungsprozeß wiederum verglimmen macht, abdämmern macht.

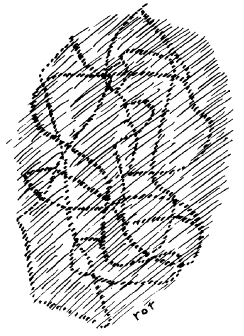

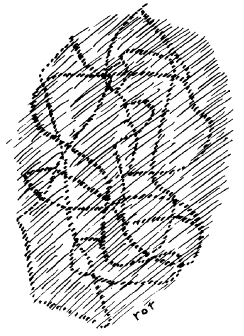

Also der Mensch konnte lernen, wie die Welt in ihm wiedergeboren wird in vielen Gestalten, so daß er eine innerlich gestaltete Welt erlebte. Aus seinem innerlichen Lebenswasser tauchte ätherisch die ganze Welt innerlich auf (siehe Zeichnung, Linien). Das war altes Hellsehen. Das ist aber ein wirklicher Prozeß, ein wirklicher Vorgang. Und im neueren Menschen ist der Vorgang auch vorhanden, nur kann er ihn nicht innerlich erleben.

Jene Wesenheiten nun, mit denen der alte Weise wirkliche Verhältnisse eingehen konnte, die wiesen ihn nicht bloß auf sein Lebenswasser hin, aus dem heraus geboren wurde dieser Mikrokosmos, sondern auf seine Lebensluft, auf das, was der Mensch als Luft mit dem Atem aufnimmt und in seinem ganzen Organismus ausbreitet. Was da ausgebreitet wird, das ergießt sich gewissermaßen wiederum über diesen ganzen Mikrokosmos, macht die Gestalten, die drinnen sind, undeutlich (rote Schraffur auf der Zeichnung). Die wunderbar ätherisch gestaltete kleine Welt beginnt, indem der Atem über sie kommt, da und dort, man möchte sagen, abzudämmern, undeutlich zu werden. Das, was vielgestaltet war, wird eines, deshalb, weil in dem Luftförmigen der astralische Mensch lebt, so wie in dem Wässerigen der ätherische Mensch lebt. Der astralische Mensch lebt darinnen, und durch den Zusammenbruch der ätherischen Gedanken, durch die Umwandlung der ätherischen Gedanken in Kraft, durch das Astralische im Luftmenschen wird der Wille geboren, und mit dem Willen die Wachstumskräfte, die verwandt sind mit dem Willen.

Wiederum haben wir nicht das abstrakte Wort Wille, sondern einen konkreten Vorgang. Wir haben den konkreten Vorgang, daß das Astralische das Luftförmige ergreift und sich über dasjenige, was ätherisch-wässerig ist, ausbreitet. Und dadurch geschieht wirklich ein Prozeß, wie er äußerlich in der Natur sich darstellt auf einer andern Stufe, wenn das Gestaltete verbrannt wird. Diesen Prozeß aber faßte man in alten Zeiten als den Sulfurprozeß auf. Und aus dem Sulfurprozeß heraus entwickelte sich dasjenige, was dann seelisch erlebt wird als der menschliche Wille.

Man sagte in alten Zeiten nicht das abstrakte Wort Denken für etwas bloß Bildhaftes, sondern wenn man vom Denken sprach und ein wirklich Erkennender war, so sprach man von dem Ihnen eben geschilderten Salzprozeß. Man sprach nicht in abstrakter Weise von dem Willen, sondern man sprach, wenn man ein Erkennender war, von dem Erfassen des vom Astralischen durchsetzten Luftförmigen, von dem Sulfurprozeß, in dem der Wille urständet, der angeschaute Wille. Und man sagte, daß der Ausgleich zwischen beiden — denn es sind ja entgegengesetzte Vorgänge — durch den Merkurprozeß vollzogen wird, durch dasjenige, was gestaltet und flüssig ist, was hin- und herpendelt gewissermaßen von dem Ätherischen zu dem Astralischen, von dem Wässerigen zu dem Luftförmigen.

Solche abstrakten Ideen, wie sie die Scholastik allmählich ausgebildet hat und wie sie die moderne Naturwissenschaft übernommen hat, gab es ja für die alten Denker gar nicht. Solche alten Denker wären sich vorgekommen, wenn man ihnen unsere Begriffe von Denken, Fühlen und Wollen gegeben hätte, wie ein Laubfrosch, den man unter den ausgepumpten Rezipienten einer Luftpumpe, in einen luftleeren Raum setzt. So wären sich die alten Denker vorgekommen mit unseren abstrakten Begriffen. Sie hätten gedacht: Damit laßt sich ja nicht seelisch leben, da kann man ja nicht seelisch Luft schnappen. Es wäre für sie überhaupt gar nichts gewesen. Sie sprachen nicht von einem bloßen abstrakten Willensprozeß, von einem bloßen abstrakten Denkprozeß, sondern von einem Salzprozeß, von einem Sulfurprozeß, und meinten damit etwas, was auf der einen Seite geistig-seelisch, aber auf der andern Seite materiellätherisch war. Das war für sie eine Einheit, und sie durchschauten das Weltwirken, indem die Seele überall im Körperlichen wirkte, das Körperliche überall vom Seelischen ergriffen war.

In den Schriften des Mittelalters, die hinaufreichen bis zum 13., 14., 15. Jahrhundert, da spukt noch nach diese alte Anschauung, die von Inhalt erfüllte, aber innerlich erlebte Erkenntnisse hatte. Die waren erstorben in der Zeit, in der Giordano Bruno, Jakob Böhme, Baco von Verulam lebten. Die Ideen waren abstrakt geworden. Der Mensch war angewiesen darauf, nicht mehr in sich hinein, sondern hinaus in die Natur zu schauen. Ich sagte Ihnen, die alten Denker wären sich mit unseren Ideen vorgekommen wie ein Laubfrosch unter dem Rezipienten der Luftpumpe. Aber wir können diese Ideen doch haben. Die meisten Menschen denken sich allerdings nichts, wenn sie von Denken, Fühlen und Wollen reden, als höchstens die Spiegelbilder der äußeren Natur, die im Menschen vorkommen. Aber man kann sich gerade in der neueren Zeit etwas erringen, was man in der alten Zeit nicht konnte. Man ist gewissermaßen von der Selbsttätigkeit, die von innen heraus zum Erkennen kommt, verlassen worden. In der Zwischenzeit, die sich da gebildet hat seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, findet der Mensch nichts mehr, wenn er bloß in sein Inneres schaut. Er schaut hinaus in die Natur, da macht er sich abstrakte Begriffe. Aber nun können diese abstrakten Begriffe eben äußerlich wiederum intensiviert werden, können wiederum zum Inhalt werden, weil sie erlebt werden können. Damit ist man ja allerdings jetzt erst im Anfange, aber diesen Anfang möchte anthroposophische Geisteserkenntnis machen.

All die Prozesse aber, auf die ich Ihnen da hingedeutet habe, dieser Salzprozeß, dieser Sulfurprozeß, sind ja Prozesse, die sich in der außerlichen Natur gar nicht vollziehen. Es sind Prozesse, die der Mensch nur erkennen konnte in seinem Innern. In der äußeren Natur vollziehen sie sich nicht. In der äußeren Natur vollzieht sich etwas, was zu diesen Prozessen sich so verhält wie die Prozesse in einem Leichnam zu den Prozessen in dem lebenden Menschen.

Wenn die heutige Chemie von Sulfurprozessen, von Salzprozessen redet, so verhalten sich diese Sulfur-, diese Salzprozesse zu dem, was Jakob Böhme noch aus der Volksweisheit aufnahm, wie sich die Vorgänge in einem Leichnam zu den Vorgängen im lebendigen Menschen verhalten. Es ist alles tot, wahrend diese alten Anschauungen innerliches Leben hatten. Man sah also hinein in eine neue Welt, die um den Erdenmenschen herum nicht ist. Dadurch aber hatte man die Gabe, mit Hilfe der selbsterlebten Erkenntnis dasjenige zu sehen, was nicht um den Erdenmenschen herum ist, sondern was einer andern Welt angehörte. In dem Augenblicke, wo man ernsthaftig etwas weiß über diese Salz- und Sulfurprozesse, sieht man eben hinein in das vorirdische Menschenleben. Denn das irdische Leben unterscheidet sich von dem vorirdischen Menschenleben dadurch, daß die lebendigen Sulfur- und Salzprozesse hier in der äußeren Sinneswelt als erstorben erscheinen. Was wir zwischen Geburt und Tod um uns herum durch unsere Sinne ertötet wahrnehmen, das ist in jenen Sulfur- und Salzprozessen lebendig, aber wir erleben es im vorirdischen Dasein. Das heißt, diese Prozesse, von denen Jakob Böhme noch stammelt, wirklich verstehen, gilt gleich mit dem Hineinschauen ins vorirdische Dasein.

Daß Jakob Böhme von diesem vorirdischen Dasein nicht spricht, das kommt eben davon her, weil er es nicht wirklich, sondern eben nur stammelnd hatte. Diese Fähigkeit des Menschen, hineinzublikken in das vorirdische Dasein, ist verlorengegangen, vergangen damit auch jene Verbindung mit den geistigen Wesenheiten der Welt, die auf das nachirdische Dasein hinweisen aus dem Sulfurprozeß. Die ganze Seelenverfassung des Menschen ist eben eine andere geworden. Und in diese Umwandlung der Seelenverfassung waren Giordano Bruno, Jakob Böhme und Baco von Verulam hineingestellt.

Ich habe schon gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß ja von der Art und Weise, wie der Mensch in älteren Epochen in die Welt hineingestellt war, heute die Menschen keinen blauen Dunst mehr haben. Daher würdigen sie Nachrichten, die aus verhältnismäßig gar nicht langer Vergangenheit herrühren, nicht stark. Ich habe hingewiesen auf die grandiose Idee von der Entstehung des Merlin. Wir können auch auf anderes hinweisen. Sehen Sie, wir führen jetzt das Dreikönigsspiel auf, haben es wiederholt aufgeführt. Aber diese Erzählung von dem Besuch der drei Könige bei dem Jesuskinde wird auch in dem altgermanischen Liede von dem «Heliand» gegeben. Sie wissen, das führt in verhältnismäßig frühe Zeiten des Mittelalters zurück, entsteht in Mitteleuropa. Aber da ist etwas sehr Merk würdiges. Da vernehmen wir, daß noch etwas anderes geknüpft wird an diesen Besuch der drei Könige aus dem Morgenlande. Die drei Könige erzählen nämlich im «Heliand», daß sie herkommen aus Gegenden, in denen es einmal ganz anders war als jetzt, das heißt, als in der Zeit zu Beginn unserer Zeitrechnung; denn sie seien die Nachkommen von Vorfahren, die noch unendlich viel weiser waren, als sie zu ihrer Zeit sein können. Und besonders einen Vorfahren haben sie, so erzählen diese drei Könige, der weit zurückliegt in der Zeit, aber dieser Vorfahr war noch ein solcher, der mit seinem Gotte Zwiesprache halten konnte. Und als er zu Tode kam, da versammelte dieser Vorfahr alle Glieder seiner weiten Familie und sagte ihnen, daß sein Gott ihm geoffenbart habe, es werde einstmals ein König der Welt erscheinen, den ein Stern ankündigen werde.

Und wenn man nachforscht, wo ein äußeres Zeichen dieses Vorfahren ist, so findet man — sogar die Literatur weist uns darauf hin, man kann das auch äußerlich belegen -, daß es aus dem Alten Testament im vierten Buch Mose Bileam ist; daß also diese Heiligen Drei Könige, die Könige aus dem Morgenlande, den Bileam meinen, der ein Sohn Beors ist, von dem da im vierten Buch Mose erzählt wird, wie er mit seinem Gotte Zwiesprache hält, und wie er sein ganzes irdisches Leben einrichtet im Sinne der Zwiesprache mit seinem Gotte. Wenn wir die ganze Tatsache nehmen, so finden wir einfach, daß zu der Zeit, als der Heliand in Mitteleuropa entstanden ist, noch ein Bewußtsein davon lebte, daß einstmals die Menschen mit den Göttern verkehrt haben. Eine reale Vorstellung von diesem Vorgang lebte in den Menschen.

Da haben wir wiederum etwas, was für diese Menschen in der Anschauung von der Geschichte darinnen stand und was uns eben beweist, daß wir übergegangen sind aus älteren Zeitaltern, wo die Menschen noch in einer lebendigen Welt lebten, wie ich gestern andeutete, in das Zeitalter des Philisteriums. Denn unsere Zivilisation ist im Grunde genommen die allgemeine Philisterzivilisation. Auch diejenigen, die meinen, daß sie aus dieser Philisterzivilisation herauswachsen, sind keineswegs das Gegenteil des Philisters in dem Sinne, daß sie noch in Weltenzusammenhängen leben könnten, die so grandios sind, wie etwa die Idee von Merlin oder die Tradition von Bileam als dem Urahnen der Heiligen Drei Könige. O nein, Nichtphilister sind diese Menschen nicht, höchstens Bohemiens.

Nun sehen Sie, wenn man diese Dinge sagt, dann merkt man erst, welch gewaltiger Umschwung sich in bezug auf Dinge, auf die man heute nicht die Aufmerksamkeit richtet, mit der Seelenverfassung der Menschheit vollzogen hat. Aber in gewissem Sinne hat man diese Dinge vorausgesehen. Was hat man denn schon vor Jahrhunderten gehabt? Man wußte, einstmals gab es ein, wenn auch traumhaftes Hellsehen. Da haben die Menschen hineingeschaut in solche Prozesse, wie den Sulfur-, wie den Salzprozeß. Dadurch haben sie sich die Möglichkeit erworben, in das präexistente Dasein hineinzuschauen.

Gewisse Leute, welche die Menschheit nicht aufwärts-, sondern abwärtsbringen wollten, die aber auch in einem gewissen Sinne eingeweiht waren, die sahen voraus: Diese Fähigkeit wird den Menschen verlorengehen, es wird eine Zeit kommen, wo die Menschen aus sich heraus nichts sagen können über das präexistente Leben. Und so haben sie dogmatisch festgesetzt: Es gibt überhaupt kein präexistentes Leben, des Menschen Seele wird geschaffen zugleich mit seiner physischen Erzeugung. Und die Tatsache der Präexistenz wurde dogmatisch in Dunkel gehüllt. Das war der erste Schritt, die erste Etappe, von der Erkenntnis des Menschen in der Welt zu der Unkenntnis des Menschen zu gehen. Denn man erkennt den Menschen nicht mehr, wenn man ein Stück von ihm wegnimmt, und noch dazu ein so wichtiges wie das präexistente Leben.

Nun, Jakob Böhme und Giordano Bruno und Lord Bacon lebten in der Zeit, wo man diesen Ausblick auf das präexistente Leben zugedeckt hatte. Und sie lebten in einer Zeit, in der dasjenige noch nicht vorhanden war, was nun sich aufdecken sollte: nicht mehr das innerliche Erleben, sondern das geistige Anschauen der Außenwelt, so daß man in der Außenwelt den Menschen wiederfindet, der sich nicht mehr in seinem Inneren finden kann.

Wiederum gab es schon vor langer Zeit Eingeweihte, die aber den Menschen abwärts-, nicht aufwärtsführen wollten, und die nicht aufkommen lassen wollten diese neue Einsicht, welche die umgekehrte alte Clairvoyance ist, und die daher dogmatische Mittel suchten, um an die Stelle der neuen Erkenntnis den bloßen Glauben an das nachirdische Leben zu setzen, den bloßen Glauben. Und so hatte man in der Zeit, in der Giordano Bruno wirkte, durch Menschensatzungen getilgt die Möglichkeit einer Erkenntnis des vorirdischen Menschen, die Möglichkeit einer Erkenntnis des nachirdischen Menschen. Und Giordano Bruno stand da wie ein Ringender; denn er war ein Ringender, mehr als Jakob Böhme, mehr natürlich als Lord Bacon, und er stand da mit dem Menschen der Gegenwart und konnte nicht umformen das, was ihm als Dominikanerweisheit geblieben war, in eine wirkliche Weltenansicht. Er poetisierte dasjenige, was sich ihm in einer unbestimmten Weise als eine solche Weltenansicht ergab.

Aber aus dem, was Giordano Bruno nur nebulos vor sich hatte, muß eben erstehen eine bestimmte Erkenntnis über die Welt im Menschen, über den Menschen in der Welt. Nicht in dem aus dem Inneren heraus wiedergeborenen Hellsehen, sondern aus dem frei errungenen Hellsehen heraus muß der ganze Mensch wiederum erkannt werden.

Damit habe ich Ihnen charakterisiert, was heraufziehen muß in der Menschheitsentwickelung. Und heute steht man vor der Tatsache, daß den Willen zum Heraufziehenlassen einer solchen Erkenntnis ungeheuer viele Menschen hassen, tief hassen, Feinde dieses Heraufziehens sind. Das kann auch historisch begriffen werden. Dann wird man begreifen, wie aus dem Innern heraus die feindseligen Gegnerschaften gegen anthroposophische Weltanschauung kommen.

Fifth Lecture

In continuing yesterday's reflections, I would just like to remind you that the three figures whose significance reaches back to us from the turn of the 16th to the 17th century, and whom I tried to characterize, Giordano Bruno, Baco of Verulam and Jakob Böhme, all point out to us how in them lived a struggle to understand man, to know something about the essence of man himself, and how at the same time in these three figures lived a certain inability to come to such a recognition of man. That is the characteristic thing that one can clearly see in this era, to which I referred, how an old knowledge of man has been lost and how the most honest, sincere struggle of the most outstanding spirits does not lead to a new knowledge of man.

We had to point out that from the peculiarly stammering language of Jakob Böhme something sounds like the longing to recognize the world in man, man in the world, but how from everything that Jakob Böhme brings together to such a knowledge of the world and man, something shines out which, in the present anthroposophical view, presents itself as an indication of the nature of pre-earthly man, of man before he descended to earthly existence, and yet again a clear depiction of this nature is not to be found in Jakob Böhme. I expressed this with these words: Jakob Böhme describes the nature of pre-earthly man in stammering words, but in such a way that the man he describes there actually had to die as a spiritual-soul being in the spiritual world before he could descend to earth. Jakob Böhme describes a rudiment, so to speak, of the pre-earthly man. So he is unable to really understand the world in man, man in the world.

If we then look at the poeticizing Giordano Bruno, we find a grandiose understanding of the world depicted in images. We also find the attempt to place man in this grandiose picture of the world, in other words the attempt to recognize the world in man, man in the world. But such a realization does not come about. Giordano Bruno's powerful images are beautiful and grandiose, they wander into infinities on the one hand, and into the depths of the human soul on the other. But they remain indeterminate, they even remain blurred. After all that Giordano Bruno says, we find in him a striving to represent the present human being in the spatial universe and the spatial universe itself.

While Jakob Böhme therefore refers to the pre-earthly man in an insufficient way, we see in Giordano Bruno a blurred depiction of man as he lives on earth, in connection with the spatial cosmos, which therefore also exists for the earthly man, but just insufficiently. For a really sufficiently penetrating view of the relationship of man to the cosmos for the present gives a view of the pre-earthly man and a view of the post-earthly man, as I presented a short time ago here at the Goetheanum in the so-called French Course.

And if we look again at Baco of Verulam, Lord Bacon, we find that he actually no longer has any traditional ideas about man. Of the old insights into human nature, which had come over from old clairvoyant views, and of the old mystery truths, there is nothing in Baco of Verulam. But Baco of Verulam turns his gaze out into the world which is perceptible to the senses, and assigns to the human mind the mission of combining the phenomena and things of this world of sense existence, of finding laws and so on. It thus transfers the view of the human soul into that world in which man is as a soul from the time he falls asleep until he wakes up, but there it only arrives at images of non-human nature. These images, if they are merely taken logically and abstractly, as Lord Bacon takes them, represent only external human nature. When they are experienced, then they gradually become something that gives a view of man's existence after death. For it is precisely from a real knowledge of nature that an exactly clairvoyant view of the nature of man after death can be gained. Thus, Bacon is also one who struggles for that knowledge of man in the world, of the world in man, around the turn of the 16th to the 17th century. But even his powers remain insufficient, for he did not intensify into a new experience that which appears in the mere image because an old reality is no longer present in the experience of the soul. He stands, as it were, at the gateway to the knowledge of life after death, but does not reach this knowledge.

So that we can say: Jakob Böhme still gives an insight in old traditions about the pre-earthly man, but it is insufficient. Giordano Bruno stands before a description of the world which could give him the present man, the earthly man with his soul on the one side, with his background of the cosmos on the other. However, Giordano Bruno remains with an inadequate description of the cosmos and an equally inadequate description of spiritual life, which shrinks to a mere animated monad in his view.

Lord Bacon already shows how natural science must develop, how natural science must seek the spark of the spiritual in free human knowledge out of mere matter. He points to this free human cognition, but it has no content. If it were given content, it would have to point to the post-earthly human being. He cannot do that. His cognitive ability also remains impotent.

All that which in earlier epochs of the earthly development of mankind could be drawn from the inside in living knowledge, that had passed in that time. To a certain extent, man had come to remain empty when he looked into his inner being and wanted to gain knowledge about the world from within. Man had, one might say, lost himself in a certain way, lost himself with the inner life of knowledge. And what remained was the view of the outer world, of outer nature, of that which is not human.

Jakob Böhme had, as I indicated yesterday, taken from popular wisdom something like this: Three principles live in the human being, which he called Salt, Mercury and Sulphur. These words mean something quite different in his language than they do in our modern chemical language. If you combine the terms that are commonly used in chemistry today with what Jakob Böhme stammered in a magnificent way, then this Jakob Böhme stammering no longer makes any sense at all. The words were used for something else. And what were they used for? What did even their use in the folk wisdom from which Jakob Böhme drew point to? Yes, by speaking of the action of the salty, the Mercurial, the sulphuric in man, Jakob Böhme was speaking of something concrete, something real.

When man speaks of himself today, he speaks of the soul entirely in abstractions for which he no longer receives any content; reality, actuality has passed away from the human concept. Jakob Böhme still collects the last bits, so to speak. External nature lay spread out before man, perceptible to the senses, to be combined for the intellect. But in this external nature one learned about processes, one learned about things, and then, in the following centuries up to the present day, one also built up the human being from what one was able to recognize in nature. Man had to be understood, so to speak, through the extra-human. And by trying to understand the human being through this extra-human aspect, one built up his body without knowing whether this was really true of the human being.

In a certain way, you get a kind of construction of a human ghost by combining the processes inside the human skin with the processes that you observe outside in sensual nature. But in this way you can no longer get close to the human being. If one then speaks about the human being, one speaks of thinking, feeling, willing, but these remain abstractions, they remain shadowy mental images, filled with so-called inner experiences. For these inner experiences are only reflections of outer nature. How the spiritual-soul intervenes in the human physical being was actually no longer known. And what was traditionally handed down from ancient clairvoyant knowledge was no longer understood.

What does today's anthroposophical spiritual science have to say about this? Remember some of the things that have been said about it. When we first look at the human body, we are dealing with processes that take place in connection with the senses. We are dealing with processes that take place in relation to the human being's nutrition. And we also see such processes where nutrition coincides to a certain extent with sensory perception. When man eats, he absorbs the food. So he absorbs the external substances of nature. But he tastes them at the same time. So a sensory perception mixes with a process that happens from external nature into the human being.

Let us single out just this process, that nutrition takes place in the company of taste perceptions. First we find that while the perception of taste takes place and the process of nourishment is initiated, the external substances are dissolved in the juices contained in the human organism. The external substances which the plant absorbs from inanimate nature are actually, initially in their principles, all formed. That on earth which is not formed in lifeless nature is actually fissured. We actually have to look for crystals for all substances. And those substances that we do not find in crystallized form, that we find without form or as dust and the like, are actually destroyed crystallizations. And the plant takes its substances from the crystallized lifeless nature and builds them up in the form that the plant can have. From this, in turn, the animal takes the substances and so on. So that we can say: Outside in nature everything has its form, everything has its formations. By absorbing these forms, man dissolves them. - This is the one form of process that takes place in man: the dissolution of the formed outer nature. In a sense, all this merges into the aqueous, into the fluid.

But as this now passes into the aqueous, into the liquid, when man absorbs it, he inwardly forms these shapes again from what he has first dissolved. He creates these forms. When we ingest salt, we dissolve it through the liquid of our organism, but we form within ourselves what the salt was. When we ingest a plant, we dissolve the substances of the plant, but we form them internally. But we do not form this now in the liquid, we form it in the etheric body of the human being.

Now the following is the case: If you go back to ancient times in the development of mankind, man consumed salt, for example. He dissolved it and formed what he had dissolved in his etheric body. But he could perceive this whole process inwardly, that is, he could experience the thought of the salt form from within himself. Man ate salt, he dissolved the salt, in his etheric body was the salt cube, and he knew from this: the salt has the form of the cube. And so man, by experiencing himself inwardly, also experienced nature inwardly. The thoughts of the world became his thoughts. What he experienced as imagination, as dreamlike imagination, were etherically forming formations in man, but they were the formations of the world.

Now the time had come through which man had lost this ability to inwardly experience his process of dissolution and re-formation in the etheric, and he was more and more instructed to put the question to external nature. He could no longer experience inwardly by looking at it that the salt was formed in the shape of a cube. He had to investigate external nature to find out what the shape of the salt was. Thus man was distracted from the inside and directed to the outside. The radical change to this state, that man no longer experienced the thoughts of the world inwardly in the self-perception of his etheric body, took place from the beginning of the 15th century, and had risen to a certain height, for example, in the time in which Giordano Bruno, Jakob Böhme and Baco of Verulam lived.

Jakob Böhme, however, had just absorbed the chunks of popular wisdom that actually spoke to him in this way: Man dissolves everything he takes in external substances. It is a process like dissolving salt in water. Man carries this water within him in his vital fluid. All substances, insofar as they are nutrients, are salt. This dissolves. The world thoughts on earth are expressed in the salt, in the salts. And the human being in turn shapes these world thoughts in his etheric body. That is the salt process. Thus Jakob Böhme stammeringly expressed what had been recognized in ancient times through inner experience. But if one does not illuminate what Jakob Böhme says with the means of anthroposophy, one will not be able to decipher the stammering sentences in the right way and will interpret all kinds of mystical and nebulous things into them. So that one can better say: Jakob Böhme brought together the thinking process, the process by which one imagines the world in pictures, with the salt process, with the dissolving process and the reshaping process of what has been dissolved. That was his salt process.

It is sometimes touching, if it did not at the same time betray the arrogance of many people, to see how they read Jakob Böhme and believe they understand something where he uses the word salt, while they understand nothing at all. Then they come along, hold their heads high, their noses in the air and say that they have read Jakob Böhme and that is tremendously profound wisdom. But this wisdom does not live in the interpreters, in those who make such claims. If it were not arrogant, it would even be touching how people talk about that which Jakob Böhme himself only approximately understood by taking up folk wisdom and putting it into stammering sentences.

But this points us to a completely different kind of wisdom and science of ancient times, to a wisdom that was experienced when man had the self-perception of the processes in his etheric body, which presented themselves to him as the ‘world thoughts’ repeating themselves in him. The world, constructed according to the thoughts that we see embodied in the crystallizations of the earth, which man in turn forms in his etheric body and experiences in a cognitive way: that was the old cognition that had disappeared in a certain time.

If you place yourself in an old mystery and listen to the description that such a mystery initiate has given of the universe, then something like this becomes spiritually and mentally audible - like the words that I have just spoken: Everywhere in the universe the world thoughts are at work, the Logos is at work. Look at the crystallizations of the earth! In them are embodiments of the individual words of the universal Logos.