Living Knowledge of Nature

A Task of the Anthroposophical Society

GA 220

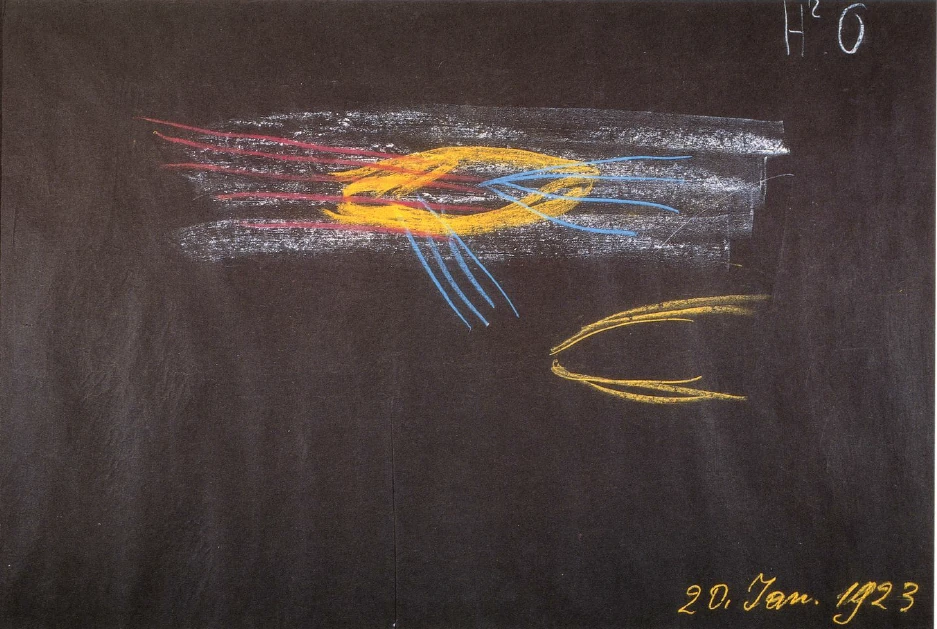

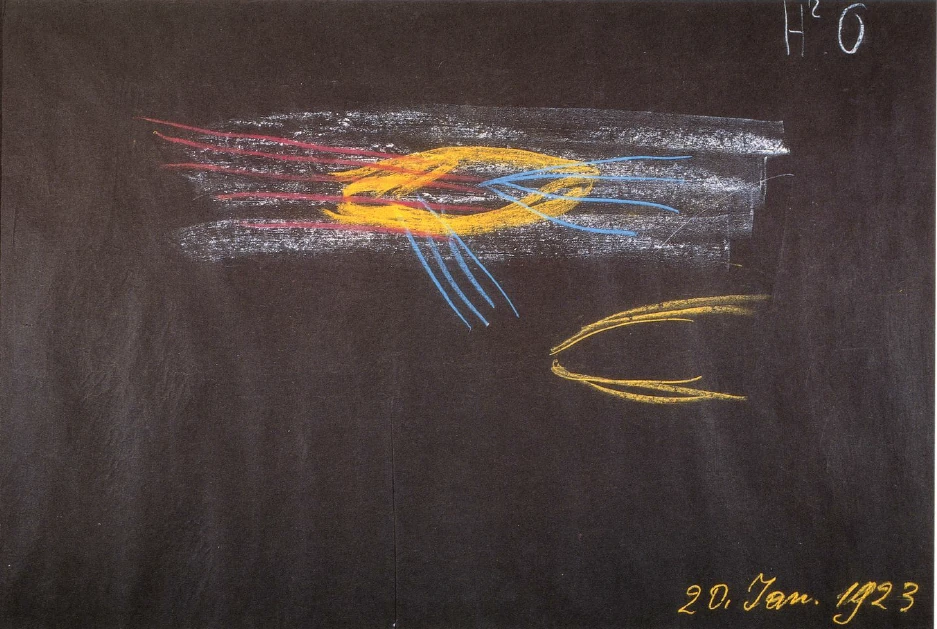

20 January 1923, Dornach

Translator Unknown

In recent lectures we have been comparing man's relationship towards Nature, towards the whole world, in olden times with that existing in our time. I pointed out, for example, how very much more concrete and actual was man's experience of Nature in more ancient times, because his inner life was much more vivid. I showed how man used to perceive his thinking process as a kind of deposition of salt in his own organism—if I may express it somewhat crudely. When man thought, he had the feeling that something hardened in his own organism. He seemed to feel the thoughts shining through his being and was aware too of a kind of etheric-astral skeleton. The sight of a cubic crystal aroused in him feelings different from those evoked by a sharply pointed one. He experienced thoughts as a hardening process within himself. Willing was to him a fiery process, a process of warmth radiating inwards.

Because man possessed such definite and vivid feelings within his own being, he could also feel outer Nature more vividly and thereby also live more concretely within it. We might say that to-day man knows little more of his inner being than the reflections cast into it by the outer world. He knows these reflections as memories and he knows the feelings, the very abstract feelings, he experiences or has experienced in connection with them; but he has lost that vivid experience of his organism being irradiated, illumined and warmed through and through. At the present time man knows of his own inner being only as much as the doctor or the scientist can tell him. Actual inner experience of his own being has ceased. Since man's external knowledge corresponds exactly to his knowledge of his own inner world, and since of this latter he knows no more than the scientist or the doctor can tell him, then also his knowledge of the outer world remains equally abstract. He informs himself about the laws of Nature but these are abstract thoughts. A really sympathetic experience of Nature is only possible in an instinctive way, though it is one which cannot be denied. Man has gradually lost knowledge of the elementary forces really working in Nature and therefore he is shut out from the rich life of Nature.

What has been preserved from former times concerning the life of Nature is now called myths and fairy tales. Certainly these myths and fairy tales express themselves in pictures, but the pictures point to something spiritual ruling in Nature. This is first of all an "elementary" spirituality expressed in indefinite outlines, but it is nevertheless spiritual, and when we penetrate through it we see a higher spirituality.

We might say that in former times man dealt not only with plants, stones, animals, but with the elementary spirits living in earth, water, air, fire, etc. When man lost himself, he also lost this experience of the Nature spirits.

A kind of dreamy resuscitation of these Nature spirits in human consciousness would not do, for it would lead to superstition. A new attitude towards Nature must lay hold of human consciousness. Man must be able to say to himself something like this: "Once upon a time men looked into themselves. They then had a lively experience of what went on within their own being. They thereby became acquainted with certain elementary spirits. When man turned his gaze inwards, those spirits began to speak to his heart and to give him that older, inner knowledge in the form of pictures which even to-day work upon us with elemental poetic force."

Those beings who were thus able to speak to man had their homes in the several human organs; for one lived as it were in the human brain, another in the human lungs, another in the human heart, etc. For man did not perceive his inner being in the way described by the anatomist to-day, he perceived it as living, active, elementary being. And when to-day with the science of initiation the path is sought to these beings, man experiences a very definite feeling about them. It seems to him that in olden times they used to speak to man through his own inner being, through each single part of this inner being. They were as if enclosed within the human skin. They inhabited the earth but they dwelt in man. They were within man, spoke to him, and gave him their knowledge. All man's knowledge of earthly existence came to him from within his own human skin.

With the development of humanity to freedom and independence these beings have lost their dwelling-place in man on the earth. They do not embody themselves in human flesh and human blood and therefore they cannot inhabit the earth in the human way; but they are still within the domain of the earth, and together with man they must reach a certain earthly goal. This is only possible if man, as it were, pays back to them what he once received from them. Then with initiation science the path to vision of these beings is trodden, it is realised that these beings once cultivated and fostered human knowledge. Much of what man is, he owes to them, for they permeated his being in his former incarnations and through them man has become what he is to-day. But they do not possess physical eyes nor physical ears. Once they lived with man. Now having left him they remain in the domain of the earth. We should recognise that once upon a time they were our teachers. Now when they have grown old we must restore to them again what they once gave to us. But that is only possible in the present phase of evolution when we approach Nature in the spirit, when we seek in the beings in Nature not only that which the abstract intellectuality of the present day seeks, but that pictorial element which is not accessible to the dead judgment of the reason but only to the developed life of feeling.

When in spirituality, that is to say, from the spiritual world-conception of Anthroposophy, we seek this pictorial element, we meet with these beings again. They may be said to observe and listen to us immersing ourselves anthroposophically in Nature; in this way they receive something from us, whereas from the ordinary knowledge of physiology and anatomy they get nothing and even have to suffer frightful deprivation. They get nothing from the lectures on anatomy nor from the operating theatres, nothing from the chemical laboratories nor the experiments in physics. They seem to ask: "Has the earth become utterly empty? Has it become a desert waste? Have they left the earth, those men to whom we once gave all we possessed? Will they not now lead us again to the things of Nature, as they alone can do?"

The fact to be realised is that there are beings who are now waiting for us to unite with them—just as we unite with other human beings on a common ground of knowledge—so that they may share in our knowledge and our actions. When a man studies physics or chemistry in the ordinary way, he is ungrateful to the fostering beings who once made him what he is. For by the side of all that man now unfolds in his consciousness these beings must starve in the domain of the earth. And man will only develop gratitude for their kindly care when again he seeks the spirit in that which he can see with his eyes, hear with his ears, and grasp with his hands. For these beings are able to share with man the spirituality permeating the perceptions of the senses. But in what is grasped in a purely material way, these beings are quite unable to participate. We human beings are only able to pay our debt of gratitude to these other beings when we really enter deeply into the content of Anthroposophy.

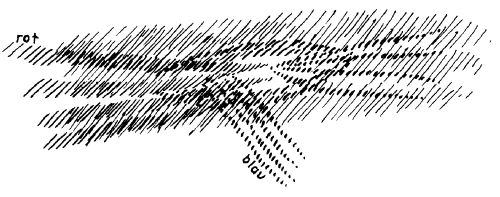

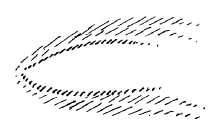

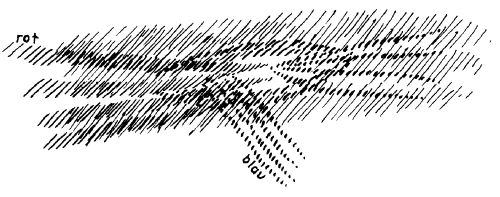

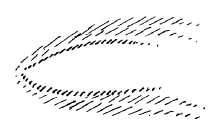

For instance, let us suppose that a man of the present day lays a fish on the table, or places a bird in a cage, and perceives it externally through his sense of sight. He is so egoistic in his knowledge that he stops at what he already perceives. Nor is it enough to picture the fish in the water or the bird in the air—this egoism only gives way when we see from the very form of the fish or of the bird, that the former is a creature of the water and by means of the water, and the latter a creature of the air and by means of the air. Let us imagine that we are observing flowing water not merely as a chemist to whom it is a chemical combination of hydrogen and oxygen, H2O, but that we look at the water in its reality. Then perhaps we find fish in it; we find that these fish consist of a soft substance developed in remarkable way into breathing organs in front; and we find that they are surrounded by a bony structure which, on account of the water, remains soft, with a delicate jaw over which the flesh, the substance of the body is laid. This bodily substance may appear to us as if proceeding out of the water, from water into which fall the rays of the sun. If we are able to perceive the sun's rays falling into this water, shining through it and warming it, and the fish swimming towards the warm illumined water, then we begin to perceive how this sun-warmth tempered by the water, and this sunlight shining in the water come towards us. This warm illumined water, together with the rhythm of the breathing, lays the soft substance of the fish's body over the jaw, and when the fish faces me with his teeth, when he comes towards me with his covered jaws and his peculiarly formed head, I feel that with this fish the shining warm water also comes towards me. And then I feel how, on the other hand, some other formative force is active in the fins. I learn gradually to perceive in the fins of the tail (I will only briefly indicate this now) and in the other fins, a tempered light, a light so tempered as to produce a substance harder than the rest of the body. Thus I learn of gradually to recognise the reflection of the sun-element in all that the fish brings towards me in its head, and the reflection of the moon-element in its hardened fins; in short, I am able to place the fish in the whole water element.

Then I look at the bird. It is impossible for the bird to develop its head in water, by swimming towards or with the sun-warmed, sun-illumined water, for the bird is adapted to the air. I learn that there is effort in its breathing. Where the breathing is not supported by water working on the gills, it becomes an effort. I perceive how the sun shines through and warms the air differently, and I become aware of the way in which the substance of the bird is pressed back from the bird's beak; I recognise that in the bird it is somewhat as if a man were to force back all the flesh that lies over his teeth thus making his jaw project. I recognise why the bird thrusts its beak towards me, whereas in the fish the jaw is held out more modestly clothed in bodily substance. I learn how the bird's head is a creation of the air, air which is everywhere filled with the warmth and light of the sun. I learn to perceive a big difference between the warm gleaming water which produces fish, and the warm illumined air which produces birds. I learn gradually to understand how, through this difference, the whole life of the bird becomes different. While the fins of the fish obtain their simple rays from the water, the bird's feathers obtain their barbs and barbules through the particular activity of the air, air that is filled with the light and warmth of the sun.

In this way I outgrow the ordinary crude view, and when the fish comes on to the table I am not too lazy to see the water as well, and when the bird is in the cage, to see the air with it. When I go further and do not limit myself to seeing the air round the bird only when it is flying in the air, but in its form I see and feel the formative element in the air, then that which lives in the forms and is filled with spirit awakens for me. In this way I learn to distinguish how differently the different animals live together with outer Nature, what a difference there is between a pachyderm, a thick-skinned animal such as a hippopotamus, and a soft-skinned animal such as a pig. I perceive that the hippopotamus has the tendency to expose his skin to the direct rays of the sun, while the pig continually withdraws his skin from the direct sunlight, preferring to withdraw into the shade. In short, I learn to recognise the particular action of Nature in each single being. My method is to pass from the several animals to the elements. I leave the path of the chemist who says that water consists of two atoms of hydrogen and one atom of oxygen! I leave the path of the physicist who tells us that air consists of oxygen and nitrogen. I pass over to concrete vision. I see the water filled with fish; I see the relationship between water and fish. To speak of water in its abstract character as hydrogen and oxygen is to be quite inadequate. In reality water, together with sun and moon, produces fish, and through the fish the elementary nature of the water speaks to my soul. To speak of the air as being a mixture of oxygen and nitrogen is too abstract—the air that is filled with light and permeated with warmth, that pushes back the flesh from the bird's beak, and that shapes the organs of breathing in fish and bird each in its own peculiar way. Through fish and bird these elements express to me their own character. What riches are brought to the inner life by this approach to Nature, what poverty by the other!

Anthroposophical spiritual science gives us opportunities everywhere to speak of things in the way just described. For Anthroposophy has no wish to be received like the products of contemporary civilization; it desires to stimulate us to a new and special perception of the world.

If what has just been characterised were to be really felt, than a gathering of people into such a society as the Anthroposophical would make this society a reality. For then every member of this Anthroposophical Society would have a certain right to say: "I return thanks to the elementary beings who were once active in my human nature and really made me what I am. Once they dwelt within my skin and spoke to me through my organs; now they have lost that possibility. But when I gaze upon the single objects in the world in this way and see how each is fashioned out of the whole of Nature, when I take seriously the descriptions in Anthroposophy, then I speak in my soul a language which these beings can understand once more. I am able to be grateful to these spiritual beings."

This is what is meant when it is said that members of the Anthroposophical Society should not merely speak of spirit in general,—the pantheist also does that,—but should be conscious of being able to live again with the spirit. Then quite of itself there would enter into the Anthroposophical Society this "living in the spirit" with other men. And it would be realised that the Anthroposophical Society is in existence for the purpose of repaying the debt we owe to those beings who nurtured us and cherished us in ancient times; then would members become aware of the reality of the spirit ruling in the Anthroposophical Society. Many of the old feelings that still live on in tradition would disappear, and be replaced by the recognition that the Anthroposophical Society has a very definite task. Then would everything else develop and be understood in its relation to life. We may indeed point with a certain inner satisfaction to the fact that during the war, when the peoples of Europe were engaged in fighting against one another, seventeen nations were working together on this Building, which has now come to such a sad end. But the reality behind the Anthroposophical Society only emerges when the various nationalities are able to burst through the narrow limitations of nationality to real unity in Anthroposophy; when behind the abstract form of the Anthroposophical Society we experience the true reality. But to this end very definite preparations are necessary.

There is a certain justification in the reproach made by the outside world against the Anthroposophists, that whereas much is said about spiritual progress there is little of it to be seen among individual Anthroposophists.

It is quite possible to make this spiritual progress; for the right reading of any one book gives this possibility. But to this end it is necessary that the content of our last lecture1Truth Beauty and Goodness, Dornach, 19.01.1923 should be taken seriously:—that the physical body is built up rightly through truthfulness, the etheric body through the sense of beauty, and the astral body through the feeling for goodness.

To speak first of truthfulness. The cultivation of truth should be a fundamental characteristic of all who really strive to unite in an Anthroposophical Society. It must first of all be acquired in life itself, and it must be something different for those who wish to develop gratitude to the beings who nurtured them in ancient times from what it is for the ignorant who prefer to remain in ignorance.

Those who do not wish to hear these things may be those who assimilate facts in accordance with their prejudices; when they desire it they may make false statements about an event or a man's character. But he who wishes to develop inner truthfulness may never go beyond what the facts of the outer world tell him. And, strictly speaking, he must always take care so to formulate his words that in respect to the outer world he only relates the facts which he has proved.

Only think how much it is the custom for people to-day to presuppose something that pleases them, and then to suppose that it is so! Anthroposophists must accustom themselves to separate all their prejudices from the true course of the facts and to describe only the pure facts. In this way Anthroposophists would of themselves act correctively in a world in which falsehood is only too often the custom.

Only think of all that is reported in the newspapers. The newspapers feel bound to report everything, no matter whether it can be proved or not. And then, when something is related, we often feel that no effort has been made to discover if the facts of the matter have been proved. If we point to this we often meet with the retort, "Why shouldn’t it be true?" With such an attitude as this we cannot acquire inner truthfulness. Anthroposophists especially should develop the capacity to describe events of the outer world in strictest accordance with the truth. Were this aim to be followed in the civilised world of the present day it would have a very remarkable result. If, through some miracle, it were to happen that a number of people were forced to coin their words in such a way as to correspond exactly to the facts, there would be widespread silence. For modern talk seldom corresponds to proved facts, but arises from all manner of opinions and passions.

It is the truth that everything we add to the outer facts apparent to the senses, everything that does not correspond to the actual facts, obliterates within us the capacity for attaining higher knowledge.

It once happened that at a gathering of students of law a little scene was carefully prepared and enacted before about twenty people. Then these twenty people were asked to write an account of what they had seen. Of course it was known exactly what had been done, for each detail had been carefully studied beforehand. Twenty people had to write an account of it afterwards. Three described it fairly accurately, seventeen wrongly. That was in a gathering of law students, where but three managed to see a fact correctly! When at the present time we listen to twenty people describing one after another something they are supposed to have seen, what they describe does not as a rule correspond in the least to the facts. We shall leave out of account altogether unusual experiences. For it has indeed happened in the fever of war that a man has taken the evening star shimmering through a cloud to be an enemy aeroplane. Certainly, such a thing may happen in a time of excitement; it is an obvious mistake. But even in everyday life great mistakes are constantly being made in regard to little things.

The growth of anthroposophical life depends upon men really acquiring this sense for the facts; it depends upon men training themselves gradually to acquire this sense for the facts, so that having observed the actual course of an outer occurrence, they do not paint in ghosts in addition when describing it afterwards. We need only read the newspapers to-day! Spectres have, of course, been done away with, but reports given in the newspapers as reliable news, are in reality nothing but spectres, phantoms of the worst kind. And the stories people relate are very often phantoms too. The first and most elementary thing we require for the ascent into the higher world is the acquisition of the sense for actual fact in the outer world. In this way only do we develop what is described in our last lecture [1] as truthfulness.

And the real feeling for beauty, as I tried to describe it vividly in my lecture, is developed in no other way than by beginning to observe the objects and beings in the world more closely,—by noticing why the bird has a beak, why the fish has that remarkable formation in front, in which a delicate jaw is hidden, etc., etc. Only by really learning to share in the life of Nature do we acquire the sense for beauty.

But it is impossible to gain a spiritual truth without a certain measure of goodness, of a sense of goodness. For man must be capable of a deep interest in his fellow men—as I was saying, morality only begins when a man feels in his own astral body the sorrows which cause the lines of care on his neighbour's brow. This is where morality begins; otherwise it is only an imitation of conventional rules or customs. What is described in my "Philosophy of Spiritual Activity" as moral action, is connected with this sympathetic experience in one's own astral body of the furrow of care, or the wrinkle caused by the smile on the countenance of another. Without this submersion of one's soul in the being of the other, it is impossible to develop the sense for the true life of the spirit.

It would therefore be an excellent foundation for the development of spirituality to have an Anthroposophical Society which is a reality, one in which each member so confronts another that he really experiences in himself that devotion to Anthroposophy felt by the other; and if the present all too human failings were not carried into the Anthroposophical Society. If the Anthroposophical Society were really a new creation whose members recognise one another as Anthroposophists—then indeed the Anthroposophical Society would be true reality. It would then be impossible for cliques and their like to appear in this society, or antipathy to a person on account of such a thing as the shape of his nose. These things which are customary in external life have entered to a large extent into the Society. In a real Anthroposophical Society personal relationships would have for their foundation mutual spiritual experiences. But the first step is the development of the sense for truth in regard to facts—which fundamentally means absolute accuracy—responsibility for one's own utterances and faithful and exact reports of the words of others.

This sense for truth is one thing. The second is the sense for the recognition of the real place of each being in the world of which it is a part—to perceive the water with the fish, the air with the bird, and then further to the sense for the understanding of our fellow men. For the sense for goodness, which is this sympathetic experience of what interests another and lives in his soul, is the third thing. Then would the Anthroposophical Society be a place where an endeavour is made towards the gradual development of the physical body, the etheric body and the astral body, each in accordance with its own purposes and its own nature. Then there would be a real beginning towards something that I have had to characterise again and again. The Anthroposophical Society should not be a society that merely enrols new members by giving each a card bearing his name and a number; it should be something that is really permeated by a common spirituality containing within itself at least the power to increase in strength and to surpass other forms of spirituality, so that at length it would mean more spiritually to a man that he should be an anthroposophist than that he should be Russian, English or German. Then only is unity really achieved.

At the present time the historic element is not yet considered essential. But it is the task of man in our time to come to the realisation of his place in history and to know that the Christian principle of universal humanity must be taken seriously: otherwise the earth loses its purpose and its inner significance. We may start by thinking of the elementary spiritual beings who long ago nurtured and fostered our human nature and remembering them with gratitude. These beings, during the last few centuries, have lost their connection with man in the civilised world of Europe and America. Man must again learn to feel gratitude towards the spiritual world. We can only arrive at the right social conditions on the earth by developing feelings of deep gratitude and love towards the beings of the spiritual world, feelings which can be present when we acquire knowledge of these beings. Then, too, feelings between man and man will change. They will be quite different from the present attitude which has had its origin in earlier conditions and has developed during recent centuries. For to-day man really regards every other human being more or less as a stranger and only himself as of importance. Yet in reality he does not know himself at all! Though he does not acknowledge it he can really only say: "Oh, I like myself best of all." If asked: "What is it in you that you like best of all?" he could only reply, "well, I must leave that to the scientist or the doctor to explain." But unconsciously, in his feelings, man really lives only in himself.

This attitude is just the opposite of what an Anthroposophical Society can give.

We must first of all realise that man must come out of himself, that the peculiarities of other men,—at least to some extent,—must interest him just as much as his own. Without this an Anthroposophical Society cannot exist. Members may be received into the Society, and, by means of rules, they may continue to hold together for a time; but that is not reality. Realities do not arise through accepting members and these members having cards on which it is stated that they are Anthroposophists. Realities never arise through anything that is written or printed, but through that which lives. The written or printed word only counts when it is an expression of life. If it is an expression of life, then a reality exists; but if what is written and printed is merely written and printed matter, the significance of which is determined by convention, then it is a corpse. For the moment I write something down I "moult" my thoughts. We know what "moulting" means; when a bird casts its feathers something dead is thrown off. When something is written down, that is a kind of "moulting". At the present time people are only too ready to "moult" their thoughts. They desire to express everything in writing. But it would be very difficult for a bird, if it had just moulted, to moult again at once. If someone were to try to make a canary moult again when it had just moulted, he would have to make imitation feathers for the purpose. Such is the case to-day. Because people only want to have dead moulted thoughts we are really no longer dealing with realities but with counterfeit realities. What men produce are chiefly imitations of reality. It is enough to drive one to despair to measure these against genuine reality. It is no longer the human being, the man, who is speaking but the government official or the solicitor or the barrister. Abstract categories speak—the "young lady", or the Dutchman or the Russian. What we must strive for is that the "man" shall speak, and not the Privy Councillor, the member of the government board, the Russian, the German, the Frenchman nor the Englishman. But first of all there must be the "man" there. But a man does not really become man so long as he only knows himself. The remarkable thing is, that just as we cannot breathe the air which we ourselves produce, neither can we live out the human being who fills our own skin, whom we feel within ourselves. We cannot breathe the air we ourselves produce; neither can we really live the human being we produce within ourselves. Our social relationships are not determined by ourselves, but by the character of others—and through what we experience in common with them. That is true humanity; that is true human life! Were we to desire to live what we produce only within ourselves, that would be the same as deciding to breathe into a vessel in order to breathe over again the same air we have ourselves produced, instead of breathing the outer air. In that case, as the physical is not as merciful as the spiritual, we should very soon die. But if a man continually breathes only what he himself experiences as a man, he also dies; though he does not know that he has died psychically, or at least spiritually.

What is really needed is that the Anthroposophical Society or Movement should, as I recently said: "Stichel!" (Wake up!) In a recent lecture I said that this anthroposophical life should be an awakening. And at the same time it must be a continual avoidance of inner death, a continual appeal to the vitality of the psychic life. In this way, the Anthroposophical Society would of itself be a reality through the inner force of the spiritual and psychic life.

Achter Vortrag

Wir haben gerade in der letzten Zeit von den Beziehungen gesprochen, welche der Mensch in älteren Zeiten zur Natur, zur ganzen Welt hatte, und von den Beziehungen, die er heute, in unserem gegenwärtigen Zeitalter dazu hat. Ich habe zum Beispiel darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wieviel realer, konkreter der Mensch in älteren Zeiten die Natur miterlebt hat, wie er die Natur deshalb konkreter miterleben konnte, weil er in sich selber auch voller erlebte. Ich habe darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie der Mensch seinen Denkprozeß einstmals empfand als eine Art - nun, wenn ich mich grob ausdrücke - Salzablagerungsprozeß im eigenen Organismus. Da verhärtet sich etwas im eigenen Organismus, so etwa fühlte der Mensch, wenn er dachte. Er fühlte gewissermaßen die Gedanken durch sein Menschenwesen hindurchstrahlen, und er fühlte eine Art ätherischastralischer Knochengerüstform. Er fühlte einen Unterschied, ob er einen Kristall ansah, der würfelförmig ist, oder einen solchen, der spitz zuläuft. Also er fühlte in sich die Gedanken wie einen Verhärtungsprozeß. Und er fühlte in sich den Willen wie einen Feuerprozeß, wie einen Prozeß der innerlich strahlenden Wärme.

Dadurch, daß der Mensch in sich so bestimmt, so voll fühlte, konnte er auch die äußere Natur voller mitfühlen und dadurch auch konkreter in dieser äußeren Natur drinnen leben. Man möchte sagen: Es ist gegenwärtig mit dem Menschen so geworden, daß er eigentlich von seinem Menscheninneren nicht viel mehr kennt als eben die Spiegelbilder, die von der Außenwelt in seinem Innern entworfen werden. Er kennt diese Spiegelbilder als Erinnerungen. Er weiß, was er gefühlsmäßig, aber sehr abstrakt gefühlsmäßig an ihnen erlebt oder erlebt hat. Aber dieses voll-lebendige Durchzuckt-, Durchstrahlt-, Durchwärmt-, Durchleuchtetwerden in seinem Organismus, das kennt der Mensch heute nicht. Der Mensch weiß heute von seinem eigenen Inneren nur so viel, als ihm der Arzt oder der Naturforscher sagen kann. Ein wirkliches inneres Erleben ist nicht mehr vorhanden. Aber alles, was der Mensch in der Außenwelt erkennt, das ist immer ganz genau entsprechend dem, was der Mensch in seiner Innenwelt erkennt. Da der Mensch heute von sich nicht viel mehr weiß als das, was ihm der Naturforscher oder der Arzt sagen kann, so bleibt er auch in bezug auf die äußere Welt abstrakt. Er erkundigt sich nur über die Naturgesetze, die abstrakte Gedanken sind. Aber ein Miterleben mit der Natur ist eigentlich nur im instinktiven Sinne, den der Mensch niemals verleugnen kann, vorhanden. Und dadurch ist dem Menschen allmählich abhanden gekommen die Einsicht, daß in der Natur wirklich elementarische Kräfte wirken. Ein reiches Leben der Natur ist dem Menschen dadurch verlorengegangen.

Der Mensch nennt heute das, was ihm aus früheren Zeiten über das Leben der Natur erhalten ist, Mythen, Märchen. Gewiß, diese Mythen und diese Märchen drücken sich in Bildern aus, aber die Bilder weisen auf ein Geistiges hin, das in der Natur waltet, das zunächst ein Elementarisch-Geistiges in unbestimmten Umrissen ist, aber das eben doch ein Geistiges ist und das, wenn man es durchdringt, dann ein höheres Geistiges zeigt. Man möchte sagen: Der Mensch ist in früheren Zeiten nicht nur mit Pflanzen, Steinen, Tieren umgegangen, sondern er ist umgegangen mit den elementarischen Geistern, die in Erde, Wasser, Luft, Feuer und so weiter leben. Indem der Mensch sich selbst verloren hat, hat er auch dieses Erleben der Naturgeister verloren.

Nun kann nicht ohne weiteres eine Art träumerischen Auflebens dieser Naturgeister im menschlichen Bewußtsein stattfinden, denn das würde zum Aberglauben führen. Es muß eine neue Art, sich zu der Natur zu verhalten, das menschliche Bewußtsein ergreifen. Man muß sich etwa sagen können: Ja, einstmals schauten die Menschen in sich selbst hinein, sie hatten ein lebhaftes Mitfühlen mit dem, was in ihrem eigenen Menschenwesen drinnen ist. Sie lernten dadurch gewisse elementarische Geister kennen. Ältere, innere Erkenntniserlebnisse, welche die Menschen in Bildern aussprachen, die heute noch mit elementarisch-poetischer Kraft auf uns wirken, waren das, was im menschlichen Inneren jene Geistigkeiten raunten, die innerlich zu dem Menschengemüte zu sprechen begannen, wenn der Mensch eben seinen Blick nach innen gewendet hatte.

Diese Wesenheiten, die eigentlich in den menschlichen Organen ihre Heimat hatten, von denen die eine sozusagen ein Bewohner des menschlichen Gehirnes, eine andere ein Bewohner der menschlichen Lunge, eine andere ein Bewohner des menschlichen Herzens war — denn man nahm ja sein Inneres nicht so wahr, wie es heute der Anatom beschreibt, sondern man nahm es als lebendig wirkende elementarische Wesenheit wahr -, diese geistigen Wesenheiten, sie konnten nun zum Menschen sprechen. Und wenn heute mit der Initiationswissenschaft der Weg zu diesen Wesenheiten gesucht wird, dann bekommt man diesen Wesenheiten gegenüber ein ganz bestimmtes Gefühl, eine ganz bestimmte Empfindung. Man sagt sich: Diese Wesenheiten sprachen einstmals durch das Menscheninnere, durch jeden einzelnen Teil dieses Menscheninneren zu dem Menschen. Sie konnten gewissermaßen nicht aus der menschlichen Haut heraus. Sie bewohnten die Erde, aber sie bewohnten sie in dem Menschen. Sie waren in dem Menschen drinnen und sprachen zu dem Menschen, gaben ihm ihre Erkenntnisse. Die Menschen konnten von dem Erdendasein nur wissen, indem sie erfuhren, was sozusagen innerhalb der menschlichen Haut von diesem Erdendasein zu erfahren ist.

Nun, mit der Entwickelung der Menschheit zur Freiheit und zur Selbständigkeit haben ja diese Wesenheiten auf Erden ihre Wohnsitze im Menschen verloren. Sie verkörpern sich nicht im menschlichen Fleische und im menschlichen Blute und können daher nicht in der Menschenart die Erde bewohnen. Aber sie sind noch immer im Erdenbereiche da, und sie müssen mit den Menschen zusammen ein gewisses Erdenziel erreichen. Das können sie nur, wenn der Mensch ihnen heute gewissermaßen zurückzahlt, was er ihnen einstmals zu verdanken hatte. Und so sagt man sich eben, wenn man mit der Initiationswissenschaft wiederum den Weg zu der Anschauung dieser Wesen hin geht: Diese Wesenheiten haben einstmals menschliche Erkenntnis gehegt und gepflegt, wir verdanken ihnen vieles von dem, was wir sind, denn sie haben uns durchdrungen in unserem früheren Lebenslauf auf Erden, und wir sind durch sie das geworden, was wir eben geworden sind. Nur haben sie nicht physische Augen noch physische Ohren. Einstmals haben sie mit den Menschen gelebt. Jetzt bewohnen sie nicht mehr den Menschen, aber sie sind im Erdenbereich da. Wir müssen uns gewissermaßen sagen: Sie waren einstmals unsere Erzieher, sie sind jetzt alt geworden, wir müssen ihnen wiederum zurückgeben, was sie uns einst gegeben haben. Das aber können wir nur, wenn wir in der heutigen Entwickelungsphase mit Geist an die Natur herandringen, wenn wir nicht nur dasjenige in den Naturwesen suchen, was die heutige abstrakte Verständigkeit sucht, sondern wenn wir das Bildhafte in den Naturwesen suchen, das, was nicht nur totem Verstandesurteile zugänglich ist, sondern was dem vollen Leben zugänglich ist, was der Empfindung zugänglich ist.

Wenn wir das in Geistigkeit, das heißt, aus dem Geiste anthroposophischer Weltanschauung heraus suchen, dann kommen diese Wesenheiten wiederum herbei. Sie schauen und hören gewissermaßen zu, wie wir uns selbst anthroposophisch in die Natur vertiefen, und sie haben dann etwas von uns, während sie von der gewöhnlichen physiologischen und anatomischen Erkenntnis nichts haben, sondern furchtbar entbehren müssen. Sie haben nichts von anatomischen Hörsälen und Seziersälen, nichts von chemischen Laboratorien und physikalischen Kabinetten. Gegenüber dem allen haben sie das Gefühl: Ist denn die Erde ganz leer, ist denn die Erde wüst geworden? Leben denn nicht jene Menschen auf Erden noch, denen wir einstmals dasjenige gegeben haben, was wir hatten? Wollen sie uns denn jetzt nicht wiederum hinführen, was sie doch alleine können, zu den Dingen der Natur?

Damit will ich nur sagen, daß es Wesen gibt, welche heute darauf warten, daß wir uns mit ihnen so vereinigen, wie wir uns mit andern Menschen in einem wirklichen Erkenntnisgefühl vereinigen, damit diese Wesenheiten teilnehmen können an dem, was wir lernen, über die Dinge zu wissen, mit den Dingen zu handeln. Wenn der Mensch heute im gewöhnlichen Sinne Physik oder Chemie studiert, so ist er gegenüber den hegenden und pflegenden Wesen, die ihn einstmals zu dem gemacht haben, was er ist, undankbar. Denn diese Wesenheiten müssen neben alledem, was der Mensch heute in seinem Bewußtsein entfaltet, im Erdenbereich erfrieren. Und dankbar wird die Menschheit erst wiederum diesen Hegern und Pflegern gegenüber, wenn sie sich dazu bequemt, für das, was sie auf der Erde mit Augen sehen, mit Ohren hören, mit Händen greifen kann, wieder den Geist zu suchen. Denn für alles, was geistig die Sinneswahrnehmungen durchdringt, haben diese Wesenheiten die Möglichkeit, es mit dem Menschen mitzuerleben. Durch das, was in bloß materieller Weise erfaßt wird, sind diese Wesenheiten nicht imstande, mit den Menschen zu leben. Sie sind ausgeschlossen davon. Wir Menschen aber können diesen Wesenheiten nur dann den Dank zollen, den wir ihnen schuldig sind, wenn wir wirklich Ernst machen mit demjenigen, was ja im Geiste anthroposophischer Weltauffassung liegt.

Nehmen wir zum Beispiel an, der heutige Mensch laßt sich einen Fisch auf den Tisch legen, er läßt sich einen Vogel in einen Käfig sperren, und er sieht äußerlich mit seinen Sinnen den Fisch an, er sieht äußerlich mit seinen Sinnen den Vogel an. Aber er ist so egoistisch in seiner Erkenntnis, daß er bei dem stehenbleibt, was unmittelbar daran haftet. Unegoistisch in der Erkenntnis wird man erst, wenn man nicht nur den Fisch im Wasser sieht und den Vogel in der Luft, sondern wenn man es schon der Form des Fisches und der Form des Vogels ansieht, daß der Fisch ein Tier aus dem Wasser und durch das Wasser ist, der Vogel ein Tier aus der Luft und durch die Luft. Man stelle sich einmal vor, daß man ein fließendes Wasser nicht bloß mit dem Verstande des Chemikers betrachtet und sagt: Nun ja, das ist eine chemische Verbindung, H2O, von Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff — sondern daß man das Wasser, wie es nun in der Realität ist, anschaut. Dann findet man vielleicht darinnen Fische; man findet diese Fische so, daß sie eine weiche Leibessubstanz in merkwürdige Atmungsgebilde nach vornehin ausbilden, und daß diese umgibt das wegen des Wassers weichbleibende Knochengerüst mit [samt] einem, ich möchte sagen, zarten Kiefer — einen Kiefer, über den sich die Körpersubstanz hinüberlegt. Diese Körpersubstanz kann einem erscheinen gleichsam unmittelbar hervorgehend aus dem Wasser, allerdings aus dem Wasser, in das die Sonnenstrahlen hineinfallen. Hat man einen Sinn dafür, daß die Sonnenstrahlen (rot) in dieses Wasser hineinfallen, es durchleuchten und erwärmen und der Fisch diesem durchleuchteten und erwärmten Wasser entgegenschwimmt, dann bekommt man ein Gefühl dafür, wie diese durch das Wasser gemilderte Sonnenwärme, wie das durch das Wasser in sich erglänzende Sonnenlicht einem entgegenkommt.

Indem mir der Fisch sozusagen entgegenschwimmt, er seine Zähne, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, entgegenträgt, aber dieses durchleuchtet-durchwärmte Wasser die weiche Fischkörpersubstanz mit dem Atmungsrhythmus über die Kiefer hinüberlegt, indem der Fisch mit der eigentümlichen Art seiner Kopfbildung mir entgegenhält seine überzogenen Kiefer, fühle ich, wie mir mit diesem Fische das durchleuchtete und durchwärmte Wasser entgegenkommt. Und ich fühle dann, wie auf der andern Seite in der Flossenbildung (blau) etwas anderes tätig ist. Ich lerne dadurch - ich will das heute nur andeuten — allmählich fühlen, wie da in der Schwanzflosse, in den andern Flossen das abgeschwächte Licht ist, das so abgeschwächte Licht, daß es nicht mehr die Körpersubstanz bezwingt zum Weichwerden, wie es da verhärtend wirkt. Ich lerne so allmählich in dem, was mir der Fisch entgegenbringt, in seinem Haupte das Sonnenhafte kennen, ich lerne so in den verhärteten Flossenbildungen das Mondartige erkennen, wie es zurückstrahlt, kurz, ich werde imstande sein, den Fisch hineinzustellen in das ganze Wasserelement.

Und ich schaue den Vogel an, der nicht die Möglichkeit hat, seinen Kopf im Wasser auszubilden, indem er dem sonnendurchwärmten, sonnendurchleuchteten Wasser entgegenschwimmt, oder mit dem sonnendurchwärmten, sonnendurchleuchteten Wasser schwimmt; den Vogel, der auf die Luft angewiesen ist. Ich lerne kennen das Anstrengende, das nun in seinem Atmen liegt, wo nicht das Wasser, das die Atmung unterstützt, auf Kiemen wirken kann, sondern wo die Atmung zu einer Anstrengung wird. Ich lerne erkennen, wie in anderer Weise das Durchwärmen der Sonne, das Durchleuchten der Sonne in der Luft wirkt, und ich werde gewahr, wie vom Vogelkiefer zurückgedrängt wird die Vogelsubstanz. Ich erkenne, wie es beim Vogel etwa so ist, wie wenn ich alles Fleisch, das an den Zähnen liegt, zurückdrängen würde und der Kiefer nach vorne verhärtet gehen würde. Ich lerne erkennen, warum mir der Vogel seinen Schnabel entgegenstreckt, während mir beim Fisch in zarterer Weise der Kiefer in Körpersubstanz hingehalten ist. Ich lerne erkennen, wie der Vogelkopf ein Geschöpf der Luft ist, aber der Luft eben, die durch die Sonne innerlich erglüht, erleuchtet wird. Ich lerne erkennen, was für ein gewaltiger Unterschied ist zwischen dem durchwärmten und durchleuchteten Wasser, das fischschöpferisch ist, und der durchwärmten und durchleuchteten Luft, die vogelschaffend ist. Ich lerne verstehen, wie durch diesen Unterschied das ganze Element, in dem der Vogel lebt, ein anderes wird; wie die Fischflosse durch das Wasserelement ihre einfache Strahlung bekommt, wie die Vogelfedern ihre Ansätze bekommen dadurch, daß da in einer bestimmten Weise hineinwirkt die Luft, in der Sonnenlicht und Sonnenwärme wirken.

Wenn ich in dieser Weise von der bloßen groben Anschauung zu einer solchen Auffassung übergehe, daß ich nicht zu faul bin, wenn der Fisch auf den Tisch kommt, das Wasser mitzusehen, und wenn der Vogel im Käfig ist, die Luft mitzusehen, wenn ich mich nicht darauf beschränke, die Luft um den Vogel herum nur dann zu sehen, wenn er in der Luft fliegt, sondern wenn ich seiner Form das Luftbildende anfühle und anschaue, dann belebt sich, dann durchgeistigt sich mir dasjenige, was schon in den Formen lebt. Und ich lerne auf diese Weise unterscheiden, was für ein Unterschied ist im Miterleben in der äußeren Natur zwischen einem Dickhäuter, einem Nilpferd meinetwillen, und einem mit weicher Haut überzogenen Tier, einem Schwein zum Beispiel. Ich lerne erkennen, daß das Nilpferd dazu veranlagt ist, seine Haut mehr dem unmittelbaren Sonnenlichte auszusetzen, das Schwein fortwährend seine Haut zurückzieht vor dem unmittelbaren Sonnenlichte, mehr eine Vorliebe hat für das, was sich dem Sonnenlichte entzieht. Kurz, ich lerne in jedem einzelnen Wesen das Walten der Natur kennen.

Ich gehe hinaus von den einzelnen Tieren zu den Elementen. Ich verlasse den Pfad des Chemikers, der da sagt, das Wasser besteht aus zwei Atomen Wasserstoff, einem Atom Sauerstoff. Ich verlasse das physikalische Betrachten, das da sagt, die Luft besteht aus Sauerstoff und Stickstoff. Ich gehe zu dem konkreten Anschauen über. Ich sehe das Wasser erfüllt von Fischen. Ich sehe die Verwandtschaft zwischen Wasser und Fisch. Ich sage: Das ist ja doch etwas ganz Ausgefallenes, wenn ich nur das Wasser in seiner Abstraktheit anspreche als Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff. In Wirklichkeit ist das Wasser mit Sonne und Mond zusammen fischschaffend, und durch die Fische spricht die elementare Natur des Wassers zu meiner Seele. Es ist bloß eine Abstraktion, wenn ich die Luft anspreche als ein Gemisch von Sauerstoff und Stickstoff, die durchleuchtete und durchwärmte Luft, die das Fleisch vom Vogelschnabel zurückschiebt und die am Fisch und am Vogel die Atmungsorgane in einer besonderen Art gestaltet. Diese Elemente sprechen mir durch Fisch und Vogel ihre besondere Eigentümlichkeit aus. Denken Sie sich, wie alles innerlich auf diese Weise reich wird, und wie alles innerlich verarmt wird, wenn man nur auf materielle Art von der Natur, die uns umgibt, spricht.

Ja, sehen Sie, zu dem, was ich jetzt eben beschrieben habe, gibt überall Veranlassung dasjenige, was uns in anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft entgegentritt. Denn das, was uns in anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft entgegentritt, will nicht in derselben Weise hingenommen werden wie die Zivilisationsprodukte der Gegenwart, sondern es will Anregung sein zu einem besonderen Anschauen der Welt.

Wenn man das fühlen würde, was ich eben jetzt habe charakterisieren wollen, dann würde ein Zusammenschluß von Menschen in einer solchen Gesellschaft, wie die Anthroposophische es ist, diese Gesellschaft zu einer Realität machen. Denn dann würde sich mit einem gewissen Recht jeder sagen, der zu dieser Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft gehört: Ich bin ein Dankbarer gegenüber den Elementarwesen, die einstmals in meiner Menschenwesenheit gewirkt haben und mich eigentlich zu dem gemacht haben, was ich heute bin, die einstmals innerhalb meiner Haut gewohnt haben und zu mir durch meine Organe gesprochen haben. Sie haben jetzt die Möglichkeit verloren, durch meine Organe zu mir zu sprechen. Wenn ich aber in dieser Weise einem jeglichen Ding der Welt ansehe, wie es herausgestaltet ist aus der ganzen Natur, wenn ich die Schilderungen, die mir in Anthroposophie gegeben werden, ernst nehme, dann spreche ich in meiner Seele eine Sprache, die diese Wesenheiten wieder verstehen. Ich werde ein Dankbarer gegenüber diesen geistigen Wesenheiten.

Das ist gemeint, wenn gesagt wird: In der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft soll nicht bloß vom Geist im allgemeinen gesprochen werden — das tut auch der Pantheist -, sondern in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft soll man sich bewußt sein, mit dem Geiste wieder leben zu können. Dann würde ja ganz von selbst in die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft einziehen dieses Im-Geist-Leben auch wiederum mit andern Menschen. Man würde sagen: Die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft ist dazu da, um unseren Hegern und Pflegern aus alten Zeiten zurückzuzahlen, was sie an uns getan haben, und man würde gewahr werden die Realität des innerhalb der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft waltenden Geistes. Und von den alten Gefühlen und den alten Empfindungen, die heute noch traditionell unter den Menschen leben, würde vieles verschwinden, und es würde sich ein reales Gefühl entwickeln von einer ganz bestimmten Aufgabe der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft. Und alles, was sich sonst ausbildet, würde jetzt erst seinen wahren Sinn erhalten.

Gewiß, wir dürfen mit einer gewissen inneren Befriedigung sagen: Ja, hier an diesem Bau, der nunmehr ein so trauriges Ende gefunden hat, haben während der Kriegszeit, als sich die Völker Europas befehdet haben, siebzehn Nationen zusammen gearbeitet. Aber dasjenige, was als Anthroposophische Gesellschaft real ist, das entsteht erst, wenn die verschiedenen Nationalitäten abstreifen, was ihnen im engen Rahmen der Nationalität anhaftet, und wenn für sie der anthroposophische Zusammenhalt ein realer wird; wenn das als etwas Reales empfunden wird, was man abstrakt anstrebt mit dem Zusammenschluß in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft. Dazu sind aber ganz bestimmte Vorbereitungen notwendig.

Es ist ein in einem gewissen Sinne berechtigter Vorwurf, den die Außenwelt den Anthroposophen macht, daß ja in der anthroposophischen Bewegung viel gesprochen wird vom geistigen Vorwärtskommen, daß man aber wenig sehe von diesem geistigen Vorwärtskommen der einzelnen Anthroposophen. Dieses Vorwärtskommen wäre durchaus möglich. Das richtige Lesen jedes einzelnen Buches gibt die Möglichkeit eines wirklichen Vorwärtskommens in geistiger Beziehung. Aber dazu ist nötig, daß diejenigen Dinge, von denen gestern gesprochen worden ist, wirklich real werden, ernsthaft genommen werden: daß der physische Leib in richtiger Weise konstituiert wird durch die Wahrhaftigkeit, der ätherische Leib durch den Schönheitssinn, der astralische Leib durch den Sinn für Güte.

Wenn wir zunächst sprechen von der Wahrhaftigkeit — diese Wahrhaftigkeit sollte sozusagen die große Vorbereiterin sein für alle, die nun wirklich anstreben, in einer Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft sich zusammenzuschließen. Wahrhaftigkeit muß zuerst im Leben erworben werden, und Wahrhaftigkeit muß etwas anderes werden für diejenigen, die dankbar werden wollen ihren Hegern und Pflegern aus alten Zeiten, als sie ist für solche, die nichts wissen und nichts wissen wollen von einem solchen Verhältnis zu den einstigen Hegern und Pflegern der Menschheit.

Diejenigen Menschen, die davon nichts wissen wollen, mögen nach ihren Vorurteilen auch die Tatsachen meistern, sie mögen, wenn ihnen etwas recht ist, sagen, es sei so oder so geschehen, sie mögen, wenn es ihnen gerade paßt, daß dieser Mensch so oder so geartet ist, sagen, er sei so oder so geartet. Wer aber innere Wahrhaftigkeit in sich ausbilden will, der darf niemals weiter gehen, als die Tatsachen der äußeren Welt zu ihm sprechen. Und er müßte eigentlich, strenge genommen, immer darauf bedacht sein, sorgfältig seine Worte so zu formulieren, daß er in bezug auf die äußere Welt nur den konstatierten Tatbestand gibt.

Denken Sie nur einmal, wie es in der heutigen Welt Sitte ist, dasjenige, was einem gefällt, irgendwie vorauszusetzen, und dazu anzunehmen, daß es so sei. Anthroposophen müßten sich angewöhnen, streng auszusondern von dem reinen Tatsachenverlauf alle ihre Vorurteile und nur zu schildern den reinen Tatsachenverlauf. Dadurch würden Anthroposophen von selbst zu einer Art von korrigierenden Wesen werden gegenüber dem, was sonst heute Sitte ist.

Denken Sie nur, was wird uns alles heute durch die Zeitungen berichtet. Die Zeitungen fühlen sich verpflichtet, alles zu berichten, gleichgültig ob irgendwie konstatiert werden kann, daß es so sei oder nicht so sei. Und dann spürt man oftmals, wenn irgend jemand etwas erzählt, wie die Bemühung fehlt, daraufzukommen, wie das konstatiert worden ist seiner Tatsächlichkeit nach. Dann hört man oftmals das Urteil: Ja, warum sollte das denn nicht so sein können? — Ganz gewiß, wenn man so an die Welt herangeht, daß man von irgend etwas, das behauptet wird, sagt: warum sollte denn das nicht sein können? — dann kann man nicht zu einer inneren Wahrhaftigkeit kommen. Denn was wir an uns erziehen im Anschauen der äußeren Sinneswelt, das muß gerade unter Anthroposophen so gestaltet werden, daß man streng stehenbleibt bei dem Konstatieren desjenigen, was in der äußeren Sinneswelt einem vor Augen getreten ist. Eine sehr merkwürdige Folge würde ja allerdings die Verfolgung eines solchen Zieles in der heutigen zivilisierten Welt haben. Wenn es durch irgendein Wunder geschehen könnte, daß viele Menschen dazu gezwungen würden, nur so ihre Worte zu prägen, wie es genau den Tatsachen entspricht, dann würde ein weitverbreitetes Verstummen entstehen. Denn das meiste, was heute geredet wird, entspricht eben nicht den konstatierten Tatsachen, sondern wird aus allerlei Meinungen, aus allerlei Leidenschaften heraus gesprochen.

Nun aber ist die Sache so, daß alles, was wir zu den äußeren Sinnesbedingungen hinzutun, und was nicht dem reinen bloßen Tatsachenverlauf entspricht - wenn wir es in Vorstellungen wiedergeben -, in uns die Fähigkeit der höheren Erkenntnis auslöscht.

Es ist einmal geschehen, daß in einem Kolleg, worin juristische Studenten gesessen haben, genau vorbereitet worden ist eine kleine Handlung, die vor etwa zwanzig Menschen ausgeführt wurde. Dann hat man diese zwanzig Menschen niederschreiben lassen, was sie gesehen haben. Natürlich wußte man ganz genau, was da getan worden war, denn jede Einzelheit war einstudiert gewesen. Zwanzig Leute sollten das hinterher aufschreiben, drei haben es halbwegs richtig aufgeschrieben, siebzehn falsch. Und das war in einem juristischen Kolleg, wo es wenigstens dazu gekommen ist, daß dreie einen Tatbestand richtig anschauten! Wenn man zwanzig Menschen heute hintereinander irgend etwas, was sie gesehen haben wollen, schildern hört, so entspricht meistens das, was sie schildern, nicht im geringsten den Tatsachen. Ich will ganz absehen davon, wenn im Menschenleben außerordentliche Momente eintreten. Da ist es ja vorgekommen unter dem Kriegsfieber, daß einer den Abendstern, der durch eine Wolke geschimmert hat, für einen fremden Flieger angesehen hat. Gewiß, solche Dinge können in der Aufregung vorkommen. Aber sie sind dann die Verirrungen im Großen. Im alltäglichen Leben in bezug auf das Kleine sind sie fortwährend vorhanden.

Aber wenn man vom Werden des anthroposophischen Lebens spricht, dann hängt das davon ab, daß dieser Tatsachensinn wirklich in die Menschen einziehe, daß sie sich sozusagen ausbilden dafür, diesen Tatsachensinn allmählich zu haben, damit sie, wenn sie die äußere Tat ihrer Tatsächlichkeit nach sehen, nicht Gespenster malen, wenn sie sie nachher schildern. Man braucht ja heute nur Zeitungen zu lesen. Nicht wahr, die Gespenster sind abgeschafft, aber was einem in den Zeitungen als sichere Nachrichten erzählt wird, sind ja lauter Gespenster in Wirklichkeit, Gespenster übelster Sorte. Und was die Leute erzählen, sind oftmals ebenso Gespenster. Darauf kommt es an, daß sozusagen das Elementarste zum Aufsteigen in die höheren Welten dieses ist: daß man sich zuerst den reinen Tatsachensinn für die sinnliche Welt aneignet. Dadurch erst kommt man zu dem, was ich gestern charakterisiert habe als Wahrhaftigkeit.

Und zu einem wirklichen Schönheitsgefühl, das ich gestern in seiner Lebendigkeit zu schildern versuchte, kommt man nicht anders, als wenn man den Anfang damit macht, den Dingen doch etwas anzusehen, also dem Vogel anzusehen, warum er einen Schnabel hat, dem Fisch anzusehen, warum er dieses eigentümliche Stanitzerl nach vorne hat, in dem sich ein zarter Kiefer verbirgt und so weiter. Wirklich lernen, mit den Dingen zu leben, das gibt erst den Schönheitssinn.

Und eine geistige Wahrheit ist ohne ein gewisses Maß von Güte, von Sinn für Güte, überhaupt nicht zu erreichen. Denn der Mensch muß die Fähigkeit haben, für den andern Menschen Interesse, Hingebung zu haben: das, was ich gestern so charakterisiert habe, daß eigentlich die Moral erst damit beginnt, wenn man in seinem astralischen Leibe die Sorgenfalten des andern selber als eine astralische Sorgenfalte ausbildet. Da beginnt die Moral, sonst wird die Moral nur Nachahmung von konventionellen Vorschriften oder Gewöhnungen sein. Was ich in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» als moralische Tat geschildert habe, das hängt zusammen mit diesem Miterleben im eigenen astralischen Leibe der Sorgenfalte oder der Falten, welche durch das Lächeln des andern entstehen und so weiter. Ohne daß im menschlichen Zusammenleben dieses Untertauchen der Seele des einen in dem Wesen des andern stattfindet, kann nicht der Sinn für das wirklich reale Leben von Geistigkeit sich ausbilden.

Daher wäre es eine besonders gute Grundlage für das Ausbilden von Geistigkeit, wenn es eine Anthroposophische Gesellschaft gäbe, die eine Realität ist, wo jeder dem andern so gegenübertritt, daß er in ihm den mit ihm gemeinsam der Anthroposophie ergebenen Menschen wirklich erlebt; wenn nicht hineingetragen würden in die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft die heutigen allzumenschlichen Gefühle und Empfindungen. Wenn die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft wirklich eine Neubildung wäre, in der als das Allererste gilt: Der andere ist eben Mit-Anthroposoph — dann würde die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft als eine Realität geschaffen werden. Dann würde es zum Beispiel unmöglich sein, daß innerhalb dieser Gesellschaft wiederum Cliquenbildungen und dergleichen auftreten, daß oftmals sogar jene Versuchung auftritt, daß das Antipathischsein von Menschen deshalb, weil ihnen die Nase so oder so gewachsen ist — was ja im äußeren Leben heute überhaupt Sitte ist —, in einem noch höheren Maße hineingetragen wird. Es würden tatsächlich die Beziehungen der Menschen zueinander dann gegründet werden können auf das, was sie gegenseitig an sich geistig erleben. Aber damit müßte eben der Anfang gemacht werden durch ein wirkliches Ausbilden des Sinnes für Wahrhaftigkeit gegenüber den Tatsachen, was im Grunde genommen einerlei ist mit der Genauigkeit, mit der Verantwortlichkeit und Pflege für exakte und genaue Wiedergabe desjenigen, was man einem andern mitteilt oder was man überhaupt sagt.

Dieser Sinn für Wahrhaftigkeit ist das eine. Und der Sinn für das Drinnenstehen eines jeden Wesens in der ganzen Welt, für das Fühlen des Wassers mit dem Fisch, der Luft mit dem Vogel, was sich dann überträgt auf den Sinn für das Verständnis des andern Menschen, das müßte das zweite sein. Und der Sinn für Güte, für dieses Miterleben all dessen, was den andern interessiert, was in der Seele des andern lebt, das müßte als das dritte walten. Dann würde die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft eine Stätte werden, in der angestrebt wird, physische Leiblichkeit, ätherische Leiblichkeit, astralische Leiblichkeit allmählich ihren Zielen und ihrem Wesen gemäß auszubilden. Dann würde ein Anfang mit dem gemacht werden, was eben von mir immer wieder und wiederum dadurch charakterisiert werden muß, daß ich sage: Die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft sollte nicht irgend etwas sein, was Karten gibt, worauf Namen stehen, und wo man bloß eingeschrieben ist, wo man die so und sovielte Nummer hat auf seiner Mitgliedskarte, sondern die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft sollte etwas sein, was von einer gemeinschaftlichen Geistigkeit wirklich durchdrungen ist, von einer Geistigkeit, die wenigstens die Anlage hat, immer stärker zu werden, immer mehr und mehr zu werden als die andern Geistigkeiten, so daß es zuletzt so würde, daß es für den Menschen mehr Bedeutung hätte, sich in der anthroposophischen Geistigkeit zu fühlen als in der russischen oder in der englischen oder in der deutschen Geistigkeit. Dann erst ist das Gemeinsame wirklich da.

Heute betrachtet man das historische Moment noch nicht als ein Wesentliches. Aber es ist den Menschen der neueren Zeit aufgegeben, ein Gefühl dafür zu haben, in der Geschichte zu leben und zu wissen, daß jetzt mit dem christlichen Prinzip der allgemeinen Menschlichkeit ernst gemacht werden muß, denn sonst verliert die Erde ihr Ziel und ihre innere Bedeutung. Man kann zuerst ausgehen von dem, daß einstmals elementarische geistige Wesen da waren, die unsere Menschheit gehegt und gepflegt haben, an die wir uns zurückerinnern sollten in Dankbarkeit; daß diese Wesenheiten in den letzten Jahrhunderten innerhalb der zivilisierten Welt Europas und Amerikas verloren haben ihren Zusammenhang mit dem Menschen; daß der Mensch lernen muß wiederum die Dankbarkeit gegenüber der geistigen Welt. Dann erst wird man auch zu richtigen sozialen Zuständen auf der Erde kommen, wenn man zu den Wesen der geistigen Welt jene starke Dankbarkeit und jene starke Liebe entwickelt, die vorhanden sein können, wenn man diese Wesenheiten als etwas Konkretes wirklich kennenlernt. Dann wird auch das Fühlen von Mensch zu Mensch ein ganz anderes werden, als es sich herausgebildet hat von älteren Zusammenhängen her, durch die Zeiten, die in den letzten Jahrhunderten abgelaufen sind, zu den neueren Zuständen, wo der Mensch jeden andern Menschen eigentlich mehr oder weniger als etwas Fremdes empfindet und nur sich selber vor allen Dingen wichtig nimmt, trotzdem er sich ja gar nicht kennt, trotzdem er eigentlich nur sagen kann, wenn er es sich auch natürlich nicht gesteht: Ach, ich habe eigentlich mich am allerliebsten. — Man kann fragen: Nun, was hast du denn da am allerliebsten? — Ja, das muß mir erst der Naturforscher sagen, oder der Arzt erklären, was das eigentlich ist, was ich da am allerliebsten habe! — Aber der Mensch ist unbewußt gefühlsmäfig eigentlich nur in sich selber lebend.

Das ist das Gegenteil von dem, was eine Anthroposophische Gesellschaft geben kann. Es muß zunächst eingesehen werden, daß der Mensch aus sich herauskommen muß, daß den Menschen, mindestens zu einem Teil, die andern mit ihren Eigentümlichkeiten ebenso interessieren müssen, wie seine eigenen Eigentümlichkeiten ihn interessieren. Wenn das nicht der Fall ist, kann eine Anthroposophische Gesellschaft nicht bestehen. Man kann Mitglieder aufnehmen, die können ja, weil man dann Regeln festsetzt, eine Weile bestehen, aber eine Realität ist das nicht. Realitäten entstehen nicht dadurch, daß man Mitglieder aufnimmt und diese Mitglieder nun Karten haben, durch die sie Anthroposophen sind. Realitäten entstehen überhaupt niemals durch das, was man schreibt oder druckt, sondern Realitäten entstehen durch dasjenige, was lebt. Und es kann das Geschriebene oder Gedruckte eben nur ein Ausdruck des Lebens sein. Ist es ein Ausdruck des Lebens, dann ist eine Realität vorhanden. Ist aber das Geschriebene und Gedruckte nur Geschriebenes und Gedrucktes, das konventionell in seiner Bedeutung festgestellt wird, dann ist es Kadaver. Denn in dem Momente, wo ich irgend etwas niederschreibe, mausere ich meine Gedanken. Sie wissen, was «mausern» heißt; wenn der Vogel seine Federn abwirft, da wird das Tote abgeworfen. Solch ein Mausern ist es, wenn ich irgend etwas aufschreibe. Heute, da streben eigentlich die Leute nur noch nach Mausern der Gedanken: sie wollen alles in Aufgeschriebenes verwandeln. Aber so einem Vogel würde es furchtbar schwer, wenn er sich eben gemausert hätte, sich gleich wieder zu mausern. Wenn irgend jemand anstreben wollte, daß ein Kanarienvogel, der sich eben gemausert hat, gleich wieder sich mausert, dann müßte er die Federn dazu nachmachen. Ja, aber so ist es heute! Weil die Leute überhaupt alles nur im toten Mauserungsprodukt haben wollen, so haben wir es eigentlich nur noch mit nachgemachten Realitäten, nicht mehr mit wirklichen Realitäten zu tun. Und meistens sind es nachgemachte Realitäten, was die Menschen von sich geben. Es ist zum Verzweifeln, wenn man das mißt an dem, was eine wirkliche Realität ist; wenn man sieht, wie gar nicht eigentlich mehr die Menschen sprechen. Es spricht ja nicht mehr der Mensch. Es spricht, nun ja, der Herr Regierungsrat oder der Herr Rechtsanwalt, es sprechen abstrakte Kategorien. Es spricht das Fräulein oder der Holländer oder der Russe. Aber was wir anstreben müssen, ist, daß nicht der Herr Hofrat, nicht der Herr Regierungsrat, nicht der Russe, nicht der Deutsche, nicht der Franzose und nicht der Engländer sprechen, sondern daß der Mensch spricht. Aber der Mensch muß doch erst wirklich da sein. Er wird aber nicht Mensch, wenn er nur sich selbst kennt. Denn das ist das Eigentümliche: Ebensowenig wie man die Luft, die man selbst erzeugt, atmen kann, ebensowenig kann man den Menschen, den man nur selber in sich ausfüllt, den man in sich selber fühlt, leben. Atmen Sie die Luft, die Sie selber in sich erzeugen! Das können Sie nicht. Aber Sie können auch den Menschen in Wirklichkeit nicht leben, den Sie selber in sich erzeugen. Sie müssen im sozialen Leben leben durch das, was die andern Menschen sind, was Sie mit den andern Menschen miterleben. Das ist wahres Menschentum, das ist wahres menschliches Leben. Das leben wollen, was man nur in sich selbst erzeugt, würde dasselbe bedeuten, wie wenn man sich entschließen wollte, statt daß man die äußere Luft in sich aufnimmt, nun in ein Gefäß hineinzuatmen, um wiederum dieselbe Luft zu atmen, die man selber als Atemluft erzeugt hat. Da würde man, weil das Physische unbarmherziger ist als das Geistige, sehr bald ersterben. Aber wenn man fortwährend nur an demselben herumatmet, was man als Mensch selber erlebt, dann erstirbt man auch, nur weiß man nicht, daß man seelisch oder wenigstens geistig gestorben ist.

Und es handelt sich darum, daß erst wirklich durch die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft oder Bewegung vollzogen wird das, was ich neulich charakterisiert habe mit den Worten aus dem Weihnachtsspiel: «Stichl, steh auf!» Ich habe es in einem der letzten Vorträge charakterisiert, daß dieses anthroposophische Leben ein Erwecken sein soll, ein Erwachen. Es muß aber zu gleicher Zeit ein fortwährendes Vermeiden des Seelentodes sein, ein fortwährender Appell an die Lebendigkeit des seelischen Lebens. Auf diese Art würde die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft von selbst durch die innere Kraft des geistig-seelischen Lebens eine Realität sein.

Eighth Lecture

We have just spoken recently about the relationships that man had with nature, with the whole world, in older times, and about the relationships that he has with it today, in our present age. I have pointed out, for example, how much more real and concretely man experienced nature in older times, how he was able to experience nature more concretely because he also experienced it more fully within himself. I have drawn attention to how man once experienced his thought process as a kind of - well, to put it crudely - salt deposition process in his own organism. Something hardens in one's own organism, that is how man felt when he thought. To a certain extent he felt the thoughts radiating through his human being, and he felt a kind of etheric-astral skeletal form. He felt a difference between looking at a crystal that was cube-shaped and one that was pointed. So he felt the thoughts within him like a hardening process. And he felt the will within himself like a process of fire, like a process of inwardly radiating warmth.

Because the human being felt so definitely, so fully within himself, he could also feel the outer nature more fully and thus also live more concretely within this outer nature. One might say that at the present time man has come to know little more of his inner self than the mirror images that the outer world creates within him. He knows these mirror images as memories. He knows what he experienced or has experienced in them emotionally, but very abstractly emotionally. But man today does not know this fully alive being flashed through, radiated through, warmed through, illuminated through in his organism. People today only know as much about their own inner being as a doctor or natural scientist can tell them. There is no longer any real inner experience. But everything that man recognizes in the outside world always corresponds exactly to what man recognizes in his inner world. Since man today does not know much more about himself than what the naturalist or the doctor can tell him, he also remains abstract with regard to the outer world. He only inquires about the laws of nature, which are abstract thoughts. But a co-experience with nature is actually only present in the instinctive sense, which man can never deny. And as a result, man has gradually lost the insight that elementary forces are really at work in nature. A rich life of nature has thus been lost to man.

Today man calls what he has preserved from earlier times about the life of nature myths, fairy tales. Certainly, these myths and fairy tales are expressed in images, but the images point to a spiritual being that rules in nature, which is initially an elemental-spiritual being in indeterminate outlines, but which is nevertheless a spiritual being and which, when one penetrates it, then reveals a higher spiritual being. One might say that in earlier times man not only dealt with plants, stones and animals, but also with the elemental spirits that live in earth, water, air, fire and so on. By losing himself, man has also lost this experience of the spirits of nature.

Now a kind of dreamy revival of these nature spirits in human consciousness cannot take place without further ado, for that would lead to superstition. A new way of relating to nature must take hold of human consciousness. One must be able to say to oneself: Yes, people once looked into themselves, they had a lively empathy with what was within their own human nature. Through this they came to know certain elemental spirits. Older, inner experiences of knowledge, which people expressed in images that still affect us today with elemental-poetic power, were what those spirits murmured within the human being, which began to speak inwardly to the human spirit when the human being had just turned his gaze inwards.

These entities, which actually had their home in the human organs, of which one was, so to speak, an inhabitant of the human brain, another an inhabitant of the human lungs, another an inhabitant of the human heart - for one did not perceive one's inner being as the anatomist describes it today, but one perceived it as a living elementary entity - these spiritual entities, they could now speak to man. And if today the path to these beings is sought with initiation science, then one gets a very specific feeling, a very specific sensation towards these beings. One says to oneself: These beings once spoke to man through the inner being, through every single part of this inner being. In a sense, they could not leave the human skin. They inhabited the earth, but they inhabited it within the human being. They were inside the human being and spoke to the human being, gave him their knowledge. People could only know about the earthly existence by experiencing what can be experienced of this earthly existence within the human skin, so to speak.

Now, with the development of humanity towards freedom and independence, these beings on earth have lost their abodes in the human being. They do not embody themselves in human flesh and human blood and therefore cannot inhabit the earth in the human species. But they are still there in the earthly realm and they must reach a certain earthly goal together with human beings. They can only do this if man today repays them to a certain extent for what he once owed them. And so one says to oneself, when one again takes the path to the view of these beings with the science of initiation: These beings once nurtured and cultivated human knowledge, we owe them much of what we are, for they have permeated us in our earlier life on earth, and through them we have become what we have just become. But they do not have physical eyes or physical ears. They once lived with humans. Now they no longer inhabit humans, but they are there in the earth realm. In a way, we have to say to ourselves: they were once our educators, they have now grown old, we have to give them back what they once gave us. But we can only do this if we approach nature with spirit in the present phase of development, if we not only seek that in the beings of nature which today's abstract understanding seeks, but if we seek the pictorial in the beings of nature, that which is not only accessible to dead intellectual judgment, but which is accessible to full life, which is accessible to sensation.

When we seek this in spirituality, that is, from the spirit of the anthroposophical world view, then these beings come to us again. They look and listen, as it were, as we ourselves immerse ourselves anthroposophically in nature, and they then have something of us, whereas they have nothing of the usual physiological and anatomical knowledge, but have to do terribly without it. They have nothing of anatomical lecture halls and dissecting rooms, nothing of chemical laboratories and physical cabinets. In the face of all this they have the feeling: Is the earth completely empty, has the earth become desolate? Are not those people still alive on earth to whom we once gave what we had? Do they not now want to lead us back to what they alone can do, to the things of nature?

With this I only want to say that there are beings who today are waiting for us to unite with them in the same way as we unite with other people in a real feeling of knowledge, so that these beings can participate in what we learn to know about things, to act with things. If man today studies physics or chemistry in the ordinary sense, he is ungrateful to the nurturing and caring beings who once made him what he is. For these beings must freeze to death in the earthly realm alongside all that the human being unfolds in his consciousness today. And humanity will only be grateful to these guardians and caretakers again when it feels comfortable to seek the spirit again for what it can see with its eyes, hear with its ears and grasp with its hands on earth. Because for everything that spiritually penetrates the sensory perceptions, these beings have the opportunity to experience it with the human being. Through what is grasped in a purely material way, these beings are not able to live with human beings. They are excluded from it. But we humans can only pay these beings the thanks we owe them if we really take seriously that which lies in the spirit of the anthroposophical world view.

Suppose, for example, that today's man has a fish placed on the table, he has a bird put in a cage, and outwardly he looks at the fish with his senses, outwardly he looks at the bird with his senses. But he is so egoistic in his cognition that he stops at what is immediately attached to it. One only becomes un-egoistic in knowledge when one not only sees the fish in the water and the bird in the air, but when one can already see from the form of the fish and the form of the bird that the fish is an animal from the water and through the water, the bird an animal from the air and through the air. Imagine that one does not merely look at flowing water with the chemist's mind and say: Well, this is a chemical compound, H2O, of hydrogen and oxygen - but that one looks at the water as it is in reality. Then perhaps one finds fish in it; one finds these fish in such a way that they form a soft bodily substance into strange respiratory formations in the foreground, and that this surrounds the skeleton, which remains soft because of the water, with [together with] a, I would say, delicate jaw - a jaw over which the bodily substance is superimposed. This bodily substance can appear to one to emerge, as it were, directly from the water, albeit from the water into which the sun's rays fall. If you have a sense that the sun's rays (red) fall into this water, illuminate and warm it, and that the fish swims towards this illuminated and warmed water, then you get a sense of how this solar warmth softened by the water, how the sunlight shining through the water in itself comes towards you.

As the fish swims towards me, so to speak, carrying its teeth, if I may put it that way, but this translucent, warmed-through water carries the soft fish body substance with the breathing rhythm over the jaws, as the fish holds its covered jaws towards me with the peculiar way it forms its head, I feel how the translucent and warmed-through water comes towards me with this fish. And then I feel how something else is at work on the other side in the formation of the fins (blue). I gradually learn - I will only hint at this today - to feel how in the caudal fin, in the other fins, there is the attenuated light, the light so attenuated that it no longer conquers the body substance to become soft, how it has a hardening effect there. In this way I will gradually learn to recognize the sun-like quality in what the fish brings to me in its head, I will learn to recognize the moon-like quality in the hardened fin formations as it radiates back, in short, I will be able to place the fish in the whole water element.

And I look at the bird that does not have the possibility of forming its head in the water by swimming towards the sun-warmed, sun-illuminated water, or swimming with the sun-warmed, sun-illuminated water; the bird that is dependent on the air. I get to know the strenuousness that now lies in its breathing, where not the water that supports breathing can act on gills, but where breathing becomes an effort. I learn to recognize how the warming of the sun, the shining through of the sun in the air works in a different way, and I become aware of how the bird's substance is pushed back by the bird's jaw. I realize how it is with the bird as if I were to push back all the flesh that is attached to the teeth and the jaw were to harden forward. I learn to recognize why the bird stretches out its beak towards me, while the fish's jaw is held out in body substance in a more delicate way. I learn to recognize how the bird's head is a creature of the air, but of the air that is inwardly glowing, illuminated by the sun. I learn to recognize what a tremendous difference there is between the warmed and illuminated water, which creates fish, and the warmed and illuminated air, which creates birds. I learn to understand how through this difference the whole element in which the bird lives becomes a different one; how the fish fin gets its simple radiation through the water element, how the bird's feathers get their beginnings through the fact that the air, in which sunlight and solar heat act in a certain way, works into it.