Man's Fall and Redemption

GA 220

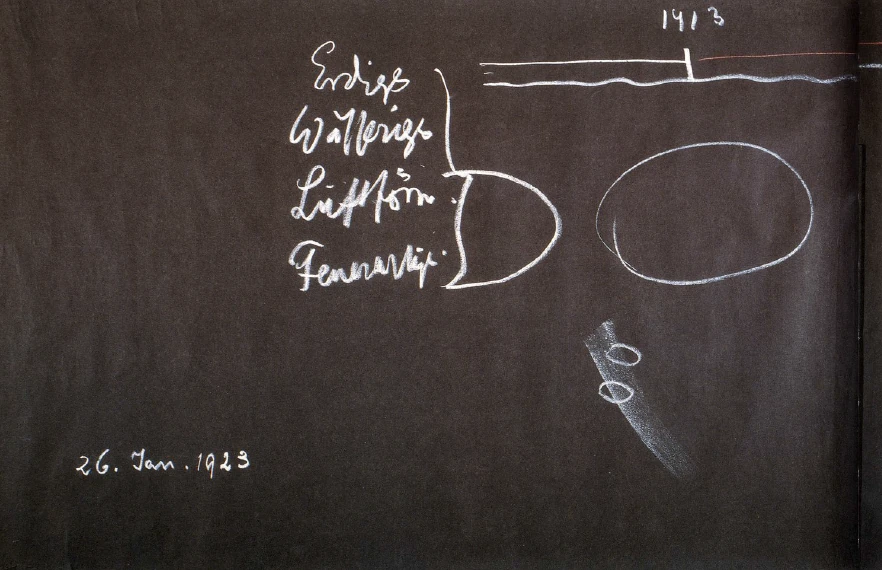

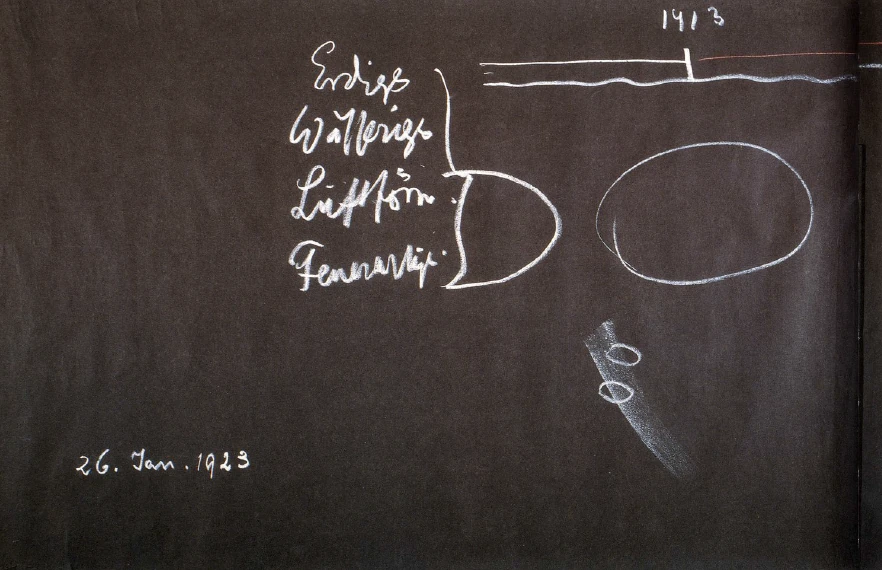

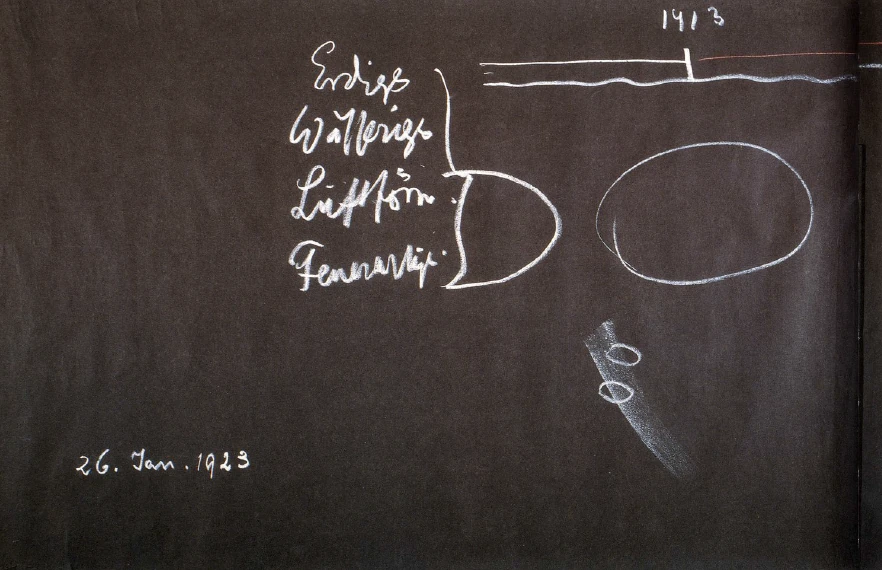

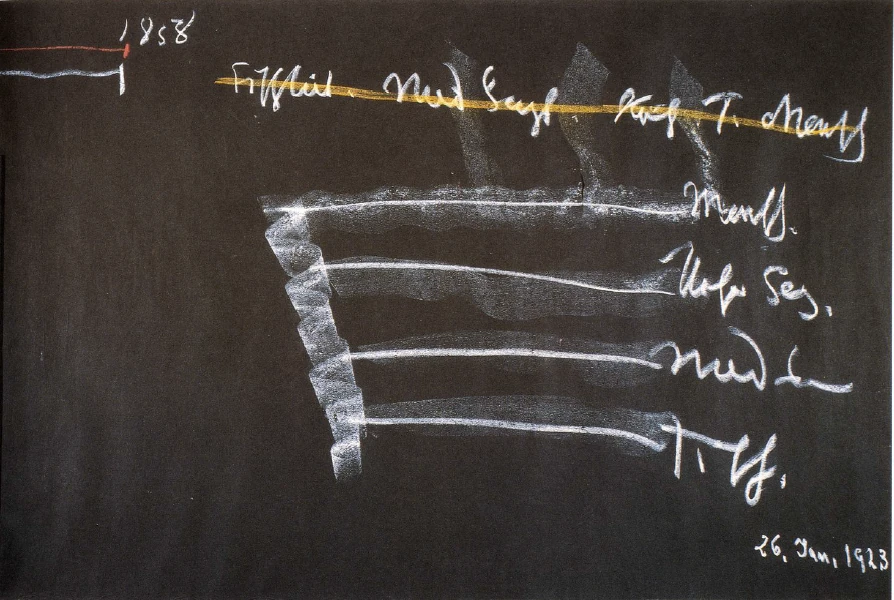

26 January 1923, Dornach

Translator Unknown

In my last lectures, I spoke of man's fall into sin and of an ascent from sin. I spoke of this ascent as something that must arise in the present age from human consciousness in general, as a kind of ideal for man's striving and willing. I have pointed out the more formal aspect of the fall of man, as it appears in the present time, by showing how the fall of man influences intellectual life. What people say concerning the limitations of our knowledge of Nature, really arises from the view that man has no inner strength enabling him to reach the spiritual, and that he must therefore renounce all efforts that might lift him above earthly contemplation. I said that when people speak to-day of the limits of knowledge, this is only the modern intellectual interpretation of how man was cast down into sin; this was felt in older times and particularly during the Middle Ages. To-day I should like to speak more from a material aspect, in order to show that modern humanity cannot reach the goal of the evolution of the earth, if the views acquired in a more recent age—especially in the course of an intellectual development—do not change. Through the consciousness of sin, the general consciousness of to-day has, to a certain extent, suffered this very fall of man. Modern intellectualism already bears the marks of this fall and decay; indeed, the decay is so strong that, unless the intellectual civilisation of the present time changes, there is no hope of attaining mankind's goal in the evolution of the earth. To-day it is necessary to know that in the depths of the human soul forces are living that are, as it were, better than the present state of the consciousness of our civilisation. It is necessary to contemplate quite clearly the nature of the consciousness of our civilisation.

The consciousness of our civilisation arose, on the one hand, from a particular conception of the thinking human being, and, on the other hand, from a particular conception of the willing human being. To-day man uses his thinking chiefly in order to know as much as possible of the outer kingdoms of Nature, and to grasp human life with the methods of thinking gained through the usual way of looking at Nature. To-day natural science teaches us to think, and we consider social life, too, in the light of this thinking, acquired through the natural sciences as they are known to-day.

Many people believe that this conception of the thinking human being, of man who observes Nature and thinks, is an unprejudiced conception. All kinds of things are mentioned that science is unprejudiced, and so on. But I have shown repeatedly that these arguments are not of much value. For, everything that a thinker applies when he is bent on his scientific investigations (according to which other people then arrange their life) has evolved from earlier ways of thinking. Modern thinking is the direct outcome of mediaeval thinking. I have pointed out already that even the arguments of the opponents of mediaeval thinking are thought out with the methods of thinking that have evolved from mediaeval thinking. An essential trait of mediaeval thinking which entered modern thinking is that the activity of thought is contemplated only in the form in which it is applied in the observation of the outer phenomena of Nature. The process of thinking is ignored altogether and there is no philosophy leading to the contemplation of thinking itself. No notice at all is taken of the process of thought and of its inner living force.

The reason for this lies in the considerations that I have already set forth. Once I said that a modern man's thoughts on Nature are really corpses, all our thoughts on the kingdoms of Nature are dead thoughts. The life of these thought corpses lies in man's pre-earthly existence. The thoughts that we form to-day on the kingdoms of Nature and on the life of man are dead while we are thinking them; they were endowed with life in our pre-earthly existence.

The abstract, lifeless thoughts that we form here on earth in accordance with modern habits of thinking were alive, were living elementary beings during our pre-earthly existence, before we descended to a physical incarnation on earth. Then, we lived in these thoughts as living beings, just as to-day we live in our blood. During our life on earth, these thoughts are dead and for this reason they are abstract. But our thinking is dead only as long as we apply it to Nature outside: as soon as we look into our own selves it appears to us as something living, for it continues working there, within us, in a way which remains concealed from the usual consciousness of to-day. There it continues to elaborate what existed during our pre-earthly life. The forces that seize our organism when we incarnate on earth, are the forces of these living thoughts. The force of these living, pre-earthly thoughts makes us grow and forms our organs. Thus, when the philosophers of a theory of knowledge speak of thinking, they speak of a lifeless thinking. Were they to speak of the true nature of thinking; not of its corpse, they would realise the necessity of considering man's inner life. There they would discover that the force of thinking, which becomes active when a human being is born or conceived, is not complete in itself and independent, because this inner activity of thought is the continuation of the living force of a pre-earthly thinking.

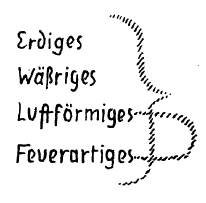

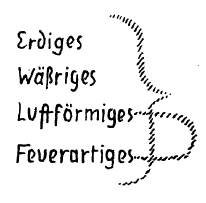

Even when we observe the tiny child (I will not now consider the embryo in the mother's body) and it's dreamy, slumbering life on earth, we can see the living force of pre-earthly thinking in its growth and even in its fretful tempers, provided we have eyes to see. Then we shall understand why the child slumbers dreamily and only begins to think later on. This is so, because in the, beginning of its life, when the child does nothing but sleep and dream, thoughts take hold of its entire organism. When the organism gradually grows firmer and harder, the thoughts, no longer seize the earthly and watery elements in the organism, but only the air element and the fire or warmth element. Thus we may say that in the tiny child thought takes possession of all four elements. The later development of a child consists in this, that thought takes hold only of the elements of air and fire. When an adult thinks, his force of thinking is contained only in the continuation of the breathing process and of the process which spreads warmth throughout his body.

Thus the force of thinking abandons the firmer parts of the physical organism for the air-like, evanescent, imponderable parts of the body. Thus thinking became the independent element that it now is, and bears us through the life between birth and death. The continuation of the pre-earthly force of thinking asserts itself only when we are asleep, i.e. when the weaker force of thinking acquired on earth no longer works in the warmth and air of the body. Thus we may say that modern man will understand something of the true nature of thinking only if he really advances towards an inner contemplation of man, of himself. Any other theory of knowledge is quite abstract.

If we bear this in mind rightly we must say that whenever we contemplate the activity that forms thoughts and ideas, our gaze opens out into pre-earthly existence.

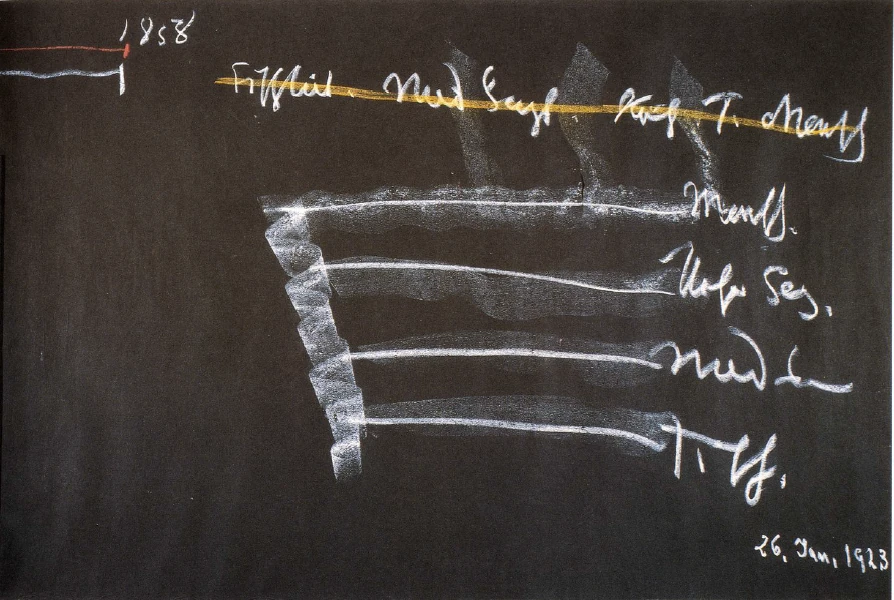

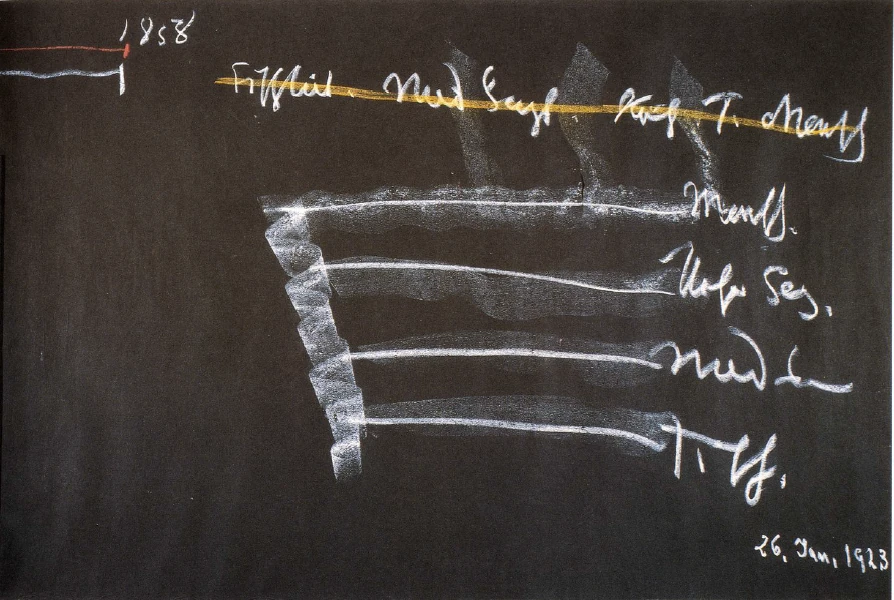

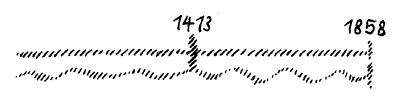

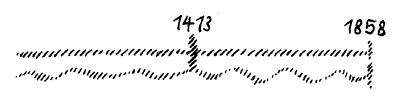

Mediaeval thinking, still possessing a certain amount of strength, was not allowed to enter pre-earthly existence. Man's pre-existence was declared dogmatically as a heresy. Something that is forced upon mankind for centuries gradually becomes a habit. Think of the more recent evolution of humanity—take, for instance, the year 1413; people habitually refrained from allowing their thoughts to follow lines that might lead them to a pre-earthly existence, because they were not allowed to think of pre-earthly existence. People entirely lost the habit of directing their thoughts to a pre-earthly existence. If men had been allowed to think of pre-earthly life (they were forbidden this, up to 1413), evolution would have taken quite another direction. In this case we should very probably have seen this is a paradox, but it is true indeed we may say that undoubtedly we should have seen that when Darwinism arose in 1858, with its exterior theories on Nature's evolution, the thought of pre-earthly existence would have flashed up from all the kingdoms of Nature, as the result of a habit of thinking that took into consideration a pre-earthly existence. In the light of the knowledge of human pre-existence, another kind of natural science would have arisen. But men were no longer accustomed to consider pre-earthly life, and a science of Nature arose which considered man—as I have often set forth—as the last link in the chain of animal evolution. It could not reach a pre-earthly, individual life, because the animal has no pre-earthly, individual life.

Therefore we can say: When the intellectual age began to dawn, the old conception of the fall of mankind was responsible for the veto on all thoughts concerning pre-existence. Then science arose as the immediate offspring of this misunderstood fall of man. Our science is sinful, it is the direct outcome of the misunderstanding relating to the fall of man. This implies that the earth cannot reach the goal of its evolution as long as the natural sciences remain as they are; man would develop a consciousness that is not born of his union with a divine-spiritual origin, but of his separation from this divine-spiritual origin.

Hence present-day talk of the limitations of knowledge is not only a theoretical fact, for what is developing under the influence of intellectualism positively shows something that is pushing mankind below its level. Speaking in mediaeval terms, we should say that the natural sciences have gone to the devil.

Indeed, history speaks in a very peculiar way. When the natural sciences and their brilliant results arose (I do not mean to contest them to-day), those who still possessed some feeling for the true nature of man were afraid that natural science might lead them to the devil. The fear of that time—a last remnant of which can be seen in Faust, when he says farewell to the Bible and turns to Nature—consisted in this, that man might approach a knowledge of Nature under the sign of man's fall and not under the sign of an ascent from sin. The root of the matter really lies far deeper than one generally thinks. Whereas in the early Middle Ages there were all kinds of traditions consisting in the fear that the devilish poodle might stick to the heels of the scientist, mankind has now become sleepy, and does not even think of these matters.

This is the material aspect of the question. The view that there are limits to a knowledge of Nature is not only a theory; the fall and decay of mankind, due to its fall in the intellectual-empirical sphere, indeed exists to-day.

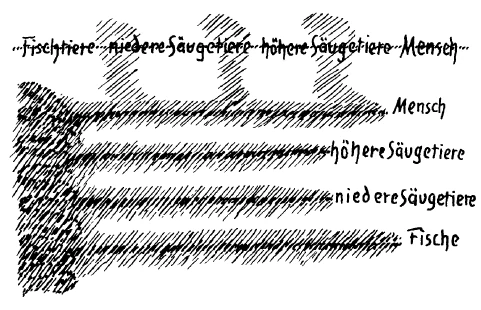

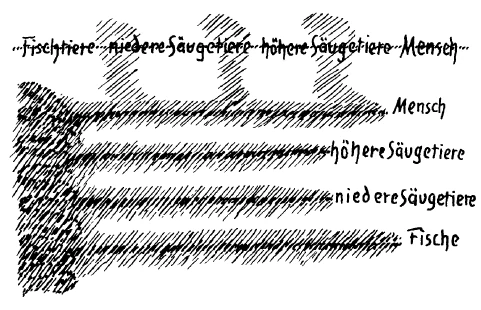

If this were not so, we should not have our modern theory of evolution. Normal methods of research would show, reality would show the following: There are, let us say, fish, lower mammals, higher mammals, man. To-day, this represents more or less the straight line of evolution. But the facts do not show this at all. You will find, along this whole line of evolution, that the facts do not coincide.

Marvels are revealed by a real scientific investigation of Nature; what scientists say about Nature is not true. For, if we consider the facts without any prejudice we obtain the following: Man, higher mammals, lower mammals, fish. (Of course, I am omitting details.) Thus we descend from man to the higher mammals, the lower mammals, etc. until we reach the source of origin of all, where everything is spiritual, and in the further evolution of man we can see that his origin is in the spirit. Gradually man assumed a higher spirituality. The lower beings, also, have their origin in the spirit, but they have not assumed a higher spirituality. Facts show us this.

Man

Higher Mammals

Lower Mammals

Fish.

Correct views of these facts could have been gained if human habits of thinking had not obeyed the veto on belief in pre-existence or pre-earthly life. Then, for instance, a mind like Darwin could not possibly have reached the conclusions set forth above; he would have reached other conclusions deriving from habits of thought, not from necessities dictated by scientific investigation.

Goethe's theory of metamorphosis could thus have been continued in a straight line. I have always pointed out to you that Goethe was unable to develop his theory of metamorphosis. If you observe with an unprejudiced mind how matters stood with Goethe, you will find that he was unable to continue. He observed the plant in its development and found the primordial plant (Urpflanze). Then he approached the human being and tried to study the metamorphosis of the human bones. But he came to a standstill and could not go on.

If you peruse Goethe's writings on the morphology of the human bony system you will see that, on the one hand, his ideas are full of genius. The cleft skull of a sheep which he found on the Lido in Venice, showed him that the skull-bones are transformed vertebrae, but he could not develop his idea further than this.

I have drawn your attention to some notes that I found in the Goethe-Archives when I was staying at Weimar. In these notes Goethe says that the entire human brain is a transformed spinal ganglion. Again, he left it at this point. These notes are jotted down in pencil in a note-book and the last pencil-marks plainly show Goethe's discontent and his wish to go further. But scientific research was not advanced enough for this. To-day it is advanced enough and has reached long ago the point of facing this problem. When we contemplate the human being, even in his earliest embryonic stages, we find that the form of the present skull-bones cannot possibly have evolved from the vertebrae of the spine. This is quite out of the question. Anyone who knows something of modern embryology argues as follows: what we see in man to-day, does not justify the statement that the skull-bones are transformed vertebrae. For this reason we can indeed say that when Gegenbauer investigated this matter once more at a later date, results proved that as far as the skull-bones and especially the facial bones were concerned, matters stood quite differently from what Goethe had assumed.

But if we know that the present shape of the skull-bones leads us back to the bones of the body of the preceding incarnation, we can understand this metamorphosis. Exterior morphology itself then leads us into the teaching of repeated lives on earth. This lies in a straight line with Goethe's theory of metamorphosis. But the stream of evolution that finally led to Darwin and still rules official science, cannot advance as far as truth. For the misunderstood fall of man has ruined thinking and has caused its decay. The question is far more serious than one is inclined to imagine to-day.

We must realise that the consciousness of mankind has changed in the course of time. For instance, we may describe something as beautiful. But if we ask a philosopher of today to explain what beauty is (for he should know something about these things, should he not?), we shall receive the most incredibly abstract explanation. “Beautiful” is a word which we sometimes use rightly, instinctively, out of our feeling. But modern man has not the slightest notion of what, for instance, a Greek imagined when he spoke of the beautiful, in his meaning of the word. We do not even know what the Greek meant by “Cosmos.” For him it was something quite concrete. Take our word “Universe.” What a confused jumble of thoughts it contains! When the Greek spoke of the Cosmos, this word held within it something beautiful, decorative, adorning, artistic. The Greek knew that when he spoke of the whole universe he could not do otherwise than characterise it with the idea of beauty. Cosmos does not only mean Universe—it means Nature's order of laws which has become universal beauty. This lies in the word “Cosmos.”

When the Greek saw before him a beautiful work of art, or when he wished to mould the form of a human being, how did he set to work? By forming it in beauty. Even in Plato's definitions we can feel what the Greek meant when he wished to form the human being artistically. The expression that Plato used means more or less the following: “Here on earth man is not at all what he should be. He comes from heaven and I have so portrayed his form that men may see in it his heavenly origin.” The Greek imagined man in his beauty, as if he had just descended from heaven, where of course, his exterior form does not resemble that of ordinary human beings. Here on earth human beings do not look as if they had just descended from heaven. Their form shows everywhere the Cain-mark, the mark of man's fall. This is the Greek conception. In our age, when we have forgotten man's connection with a pre-earthly, heavenly existence, we may not even think of such a thing.

Thus we may say that “beautiful” meant for the Greek that which reveals its heavenly meaning. In this way the idea of beauty becomes concrete. For us today it is abstract. In fact, there has been an interesting dispute between two authorities on aesthetics—the so-called “V” Vischer (because he spelt his name with a “V”), the Swabian Vischer, a very clever man, who wrote an important book on aesthetics (important, in the meaning of our age), and the formalist Robert Zimmermann, who wrote another book on aesthetics. The former, V-Vischer defines beauty as the manifestation of the idea in sensible form. Zimmermann defines beauty as the concordance of the parts within the whole. He defines it therefore more according to form, Vischer more according to content.

These definitions are really all like the famous personage who drew himself up into the air by his own forelock. What is the meaning of the expression “the appearance of the idea in sensible form?” First we must know what is meant by “the idea.” If the thought-corpse that humanity possesses as “idea” were to appear in physical shape, nothing would appear. But when we ask in the Greek sense: what is a beautiful human being? this does indeed signify something. A beautiful human being is one whose human shape is idealised to such an extent that it resembles a god. This is a beautiful man, in the Greek sense. The Greek definition has a meaning and gives us something concrete.

What really matters is that we should become aware of the change in the content of man's consciousness and in his soul-disposition in the course of time. Modern man believes that the Greek thought just as he thinks now. When people write the history of Greek philosophy—Zeller, for instance, who wrote an excellent history of Greek philosophy (excellent, in the meaning of our present age)—they write of Plato as if he had taught in the 19th century at the Berlin University, like Zeller himself, and not at the Platonic Academy. When we have really grasped this concretely, we see how impossible it is, for obviously Plato could not have taught at the Berlin University in the 19th century. Yet all that tradition relates of Plato is changed into conceptions of the 19th century, and people do not realise that they must transport their whole disposition of soul into an entirely different age, if they really wish to understand Plato.

If we acquire for ourselves a consciousness of the development of man's soul-disposition, we shall no longer think it an absurdity to say: In reality, human beings have fallen completely into sin, as far as their thoughts about external Nature and man himself are concerned.

Here we must remember something which people today never bear in mind—indeed, something which they may even look upon as a distorted idea. We must remember that the theoretical knowledge of to-day, which has become popular and which rules in every head even in the farthest corner of the world and in the remotest villages, contains something that can only be redeemed through the Christ. Christianity must first be understood in this sphere.

If we were to approach a modern scientist, expecting him to understand that his thinking must be saved by the Christ, he would probably put his hands to his head and say: “The deed of Christ may have an influence on a great many things in the world, but we cannot admit that it took place in order to redeem man from the fall into sin on the part of natural science.” Even when theologians write scientific books (there are numerous examples in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, one on ants, another on the brain, etc., and in most cases these books are excellent, better than those of the scientists, because the style is more readable), these books also breathe out, even more strongly, the need of taking a true Christology seriously. This means that particularly in the intellectual sphere we need a true ascent from sin, which must work against man's fall.

Thus we see that intellectualism has been contaminated by what has arisen out of the misunderstandings relating to the consciousness of sin—not out of the Fall as such, but from the misunderstandings with regard to the consciousness of sin. This consciousness of sin, which can be misunderstood so easily, must place the Christ in the centre of the evolution of the earth, as a higher Being, and from this point it must find the way out from the Fall. This requires a deeper and more detailed study of human evolution, also in the spiritual sphere.

You see, if we study mediaeval scholasticism as it is usually studied to-day, let us say as far back as Augustine, we shall achieve nothing. Nothing can result, because nothing is seen except that the modern scientific consciousness continues to evolve. The higher things, extending beyond this, are ignored.

In this hall I once tried to give an account of mediaeval scholasticism, showing all the connections. I gave a short course of lectures on Thomism and all that is connected with it. But it is a painful fact, and one that is of little help to our anthroposophical movement, that such ideas are not taken up. The relationship between the brilliant scientific conditions of to-day and the new impulse which must enter science is not sought. If this is not sought, then our scientific laboratories, which have cost so much real sacrifice, will remain unfruitful.

For these, progress would best be achieved by taking up such ideas and by avoiding futile discussions on atomism. In all spheres of fact, modern science has reached a point where it strives to cast aside the mass of sterile thoughts contained in modern scientific literature. Enough is known of the human being, anatomically and physiologically, to reach, by the right methods of thoughts, even such a bold conclusion as that of the metamorphosis of the form of the head from the bodily form of the preceding life. Naturally, if we cling to the material aspect, we shall not reach this point. Then we shall argue, very intelligently, that the bones must in this case remain physical matter, in order that they may undergo a gradual material metamorphosis in the grave! It is important to bear in mind that the material form is an external form and that it is the formative forces that undergo a metamorphosis.

On the one hand thinking has been fettered, because darkness has been thrown over pre-existence. On the other hand, we are concerned with post-existence, or the life after death. Life after death can be understood only with the aid of super-sensible knowledge. If super-sensible knowledge is rejected, life after death remains an article of faith, accepted purely on the ground of authority. A real understanding of the process of thinking leads to a pre-existent life, provided such thoughts are not forbidden. A knowledge of post-existent life can, however, only be acquired through super-sensible knowledge. Here the method described in my “Knowledge of the Higher Worlds” must be introduced. But this method is rejected by the consciousness of our times.

Thus two influences are at work: on the one hand, the continued effects of the decree prohibiting thought on man's pre-existence; on the other hand, the rejection of super-sensible knowledge. If both continue to work, the super-sensible world will remain an unexplored region, inaccessible to knowledge, i.e. it will remain an article of faith, and Christianity, too, will remain a matter of faith, not of knowledge. And Science, that claims the name of “science,” will not allow itself to have anything to do with the Christ. Thus we have our present-day conditions.

At the beginning of to-day's considerations, I said, with regard to the consciousness that is filled to-day with intellectualism, that humanity has slipped entirely into the consequences of the Fall. If this persists, humanity will be unable to raise itself. This means that it will not reach the goal of the evolution of the Earth. Modern science makes it impossible to reach the goal of the evolution of the Earth. Nevertheless, the depths of the human soul are still untouched: If man appeals to these soul-depths and develops super-sensible knowledge in the spirit of the Christ-impulse he will attain redemption once more, even in the intellectual sphere redemption from the intellectual forces, that have fallen—if I may express it in this way—into sin.

Consequently, the first thing which is needed is to realise that intellectual and empirical scientific research must become permeated with spirituality. But this spirituality cannot reach man as long as the content of space is investigated merely according to its spatial relationships, and the events taking place in the course of time are investigated merely in their chronological sequence.

If you study the shape of the human head, especially with regard to its bony structure, and compare it with the remainder of the skeleton (skull-bones compared to cylindrical bones, vertebrae and ribs) you will obtain no result whatever. You must go beyond time and space, to conceptions formed in spiritual science, for these grasp the human being as he passes from one earthly life to another. Then you will realise that to-day we may look upon the human skull-bones as transformed vertebrae. But the vertebrae of the present skeleton of a human being can never change into skull-bones in the sphere of earthly existence. They must first decay and become spiritual, in order to change into skull-bones in the next life on earth.

An instinctively intuitive mind like Goethe's sees in the skull-bones the metamorphosis of vertebrae. But spiritual science is needed in order to pursue this intuitive vision as far as the domain of facts. Goethe's theory of metamorphosis acquires significance only in the light of spiritual science. For this reason it could not satisfy even Goethe. This is why a knowledge gained through anthroposophical science is the only one that can bring man into a right relationship to the Fall and the re-ascent from sin. For this reason too, anthroposophical ideas are to-day something which seeks to enter into human evolution not only in the form of thoughts but as the content of life.

Zehnter Vortrag

Ich habe in den letzten Vorträgen hier gesprochen von Sündenfall und Sündenerhebung und die Sündenerhebung als etwas bezeichnet, was aus dem allgemeinen Bewußtsein der Menschheit in der gegenwärtigen Epoche als eine Art Ideal für menschliches Streben und menschliches Wollen erkannt werden muß. Nun habe ich mehr die formale Seite des Sündenfalles hervorgehoben, wie er sich noch in unserer Zeit äußert, indem ich darauf hingewiesen habe, wie in das intellektuelle Leben der Sündenfall hereinspielt. Was man über Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis sagt, das ist ja im Grunde genommen entsprungen aus der Anschauung, daß der Mensch nicht die innere Kraft habe, zum Geistigen zu kommen, daß er daher zu einer Erhebung aus dem Anschauen des Irdischen gar nicht aufstreben soll. Und ich sagte: Wenn heute gesprochen wird von den Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis, so ist das eigentlich nur die moderne intellektuelle Art, von der Sündenbedrücktheit des Menschen zu sprechen, die in älteren Zeiten und insbesondere durch die mittelalterliche Zivilisation hindurch üblich war. Ich möchte heute mehr von einer materiellen Seite der Sache sprechen und darauf hinweisen, wie die Menschheit der heutigen Zeit, wenn sie bei den Anschauungen verbleibt, die im Laufe der neueren Entwickelung, vorzugsweise im Laufe der intellektualistischen Entwickelung, heraufgezogen sind, gar nicht das Erdenziel erreichen kann. Das allgemeine heutige Bewußtsein ist nämlich gewissermaßen schon durch das Bewußtsein vom Sündenfall diesem selbst verfallen. Der Intellektualismus hat heute bereits den Charakter des Verfalls, und zwar eines so starken Verfalls, daß, wenn die intellektualistische Kultur so verbleibt, wie sie gegenwärtig gestaltet ist, von der Erreichung des Erdenzieles für die Menschheit gar nicht gesprochen werden kann. Notwendig ist heute zu wissen, daß in den Tiefen der Menschenseelen noch Kräfte walten, die gewissermaßen besser sind als die Bewußtseinskultur, welche bis heute Platz gegriffen hat.

Um das zu verstehen, ist es notwendig, sich deutlich den Charakter dieser Bewußtseinskultur vor Augen zu stellen. Diese Bewußtseinskultur ist ja entsprungen auf der einen Seite aus einer bestimmten Auffassung des denkenden Menschen, und auf der andern Seite aus einer bestimmten Auffassung des wollenden Menschen. Der fühlende Mensch liegt zwischendrinnen, und man betrachtet auch den fühlenden Menschen, wenn man einerseits den denkenden, andererseits den wollenden Menschen betrachtet. Nun verwendet heute die Menschheit ihr Denken lediglich darauf, die äußeren Naturreiche im weitesten Umfange kennenzulernen und auch das Menschenleben im Sinne der aus der gebräuchlichen Naturanschauung gewohnten Denkungsart aufzufassen. Man lernt heute denken an der Naturwissenschaft und betrachtet dann auch das soziale Leben mit diesem Denken, das man an der Naturwissenschaft, wie sie heute üblich ist, heranerzogen hat.

Nun glaubt man ja vielfach, daß diese Empfindung unbefangen ist, die man vom denkenden Menschen hat, vom Menschen, der die Natur denkend betrachtet. Man redet von allem möglichen, von Voraussetzungslosigkeit der Wissenschaft und dergleichen. Aber ich habe schon öfter betont: mit dieser Voraussetzungslosigkeit ist es nicht weit her. Denn alles, was heute der Denker anwendet, wenn er sich wissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen hingibt, nach denen sich dann die übrige Menschheit in ihrem Leben richtet, alles das hat sich ja herausentwickelt aus früheren Arten zu denken. Und zwar hat sich das neuere Denken ganz und gar herausentwickelt aus dem mittelalterlichen Denken. Auch was heute — auch das habe ich schon betont - von Gegnern des mittelalterlichen Denkens gesagt wird, wird mit den Denkmethoden gedacht, die sich selbst aus dem mittelalterlichen Denken heraus entwickelt haben. Und ein wesentlicher Charakter des mittelalterlichen Denkens ist in das heutige Denken dadurch hereingekommen, daß man das Denken selbst eigentlich nur danach betrachtet, wie es sich auf die äußere Natur anwendet, daß man den Gedankenvorgang eigentlich gar nicht betrachtet, daß man sich gar keiner Anschauung hingibt, die auf die Betrachtung des Denkens selber geht. Vom Denken selber, in seiner inneren Lebendigkeit, nimmt man ja keine Notiz.

Das geschieht aus einem Grunde, der aus meinen hier vorgetragenen Betrachtungen hervorgeht. Ich sagte einmal hier: Die Gedanken, die sich der moderne Mensch über die Natur macht, sind eigentlich Gedankenleichen. Wenn wir über die Reiche der Natur nachdenken, so denken wir in Gedankenleichen; denn das Leben dieser Gedankenleichen fällt in das vorirdische Dasein des Menschen. Was wir heute an Gedanken entwickeln über die Reiche der Natur und auch über das Leben des Menschen, das ist, indem wir denken, tot; aber es lebte in unserem vorirdischen Dasein.

In unserem vorirdischen Dasein, bevor wir heruntergestiegen sind in die physische Erdenverkörperung, da waren die abstrakten, toten Gedanken, die wir hier auf der Erde heute nach den Gepflogenheiten unseres Zeitalters entwickeln, lebendig, elementarisch-lebendige Wesenheiten. Da lebten wir in diesen Gedanken als lebendige Wesenheiten, wie wir heute hier auf der Erde etwa in unserem Blute leben. Jetzt hier für das Erdendasein sind diese Gedanken erstorben, daher abstrakt geworden. Aber nur solange wir dabei stehenbleiben, unser Denken in der Anwendung auf die äußere Natur zu betrachten, ist es ein Totes. Sobald wir in uns selbst hineinschauen, offenbart es sich uns als Lebendiges, denn da in uns selber arbeitet es weiter, auf eine allerdings für das gewöhnliche heutige Bewußtsein unbewußte Art. Da arbeitet das weiter, was in unserem vorirdischen Dasein vorhanden war. Denn die Kräfte dieser lebendigen Gedanken sind es, die von unserem physischen Organismus bei der Erdenverkörperung Besitz ergreifen. Die Kraft dieser lebendigen vorirdischen Gedanken ist es, die uns wachsen macht, die unsere Organe formt. So daß, wenn heute zum Beispiel die gebräuchlichen Erkenntnistheoretiker vom Denken sprechen, sie von etwas Totem sprechen. Denn wollten sie von der wahren Natur des Denkens, nicht von seinem Leichnam sprechen, darin müßten sie eben gewahr werden, daß sie nach innen schauen müßten, und im Innern würden sie bemerken, daß keine Selbständigkeit desjenigen vorhanden ist, was da mit der Geburt oder mit der Empfängnis des Menschen auf Erden begonnen hat, sondern daß sich in diesem innerlichen Arbeiten des Gedankens fortsetzt die lebendige Kraft des vorirdischen Denkens.

Selbst wenn wir nur das noch ganz kleine Kind betrachten - ich will gar nicht auf den Menschenkeim im mütterlichen Leibe heute Rücksicht nehmen -, selbst im kleinen Kinde, das noch sein traumhaft-schlummerndes Erdenleben führt, sehen wir an dem, was im Kinde wächst, selbst in dem, was im Kinde tobt, noch die lebendige Kraft des vorirdischen Denkens, wenn wir in der Lage sind, das anzuerkennen, was sich wirklich darbietet. Und wir werden dann gewahr, worauf es beruht, daß das Kind eigentlich noch traumhaft schlummert und erst später anfängt, Gedanken zu haben. Das beruht darauf, daß in der ersten Lebenszeit des kleinen Kindes, wo es noch traumhaft schlummert, sein ganzer Organismus von Gedanken erfaßt wird. Wenn aber der Organismus allmählich sich in sich verfestigt, dann wird nicht mehr im Organismus das Erdige und Wäßrige stark vom Gedanken erfaßt, sondern nur noch das Luftförmige und das Feuerartige, das Wärmeartige. So daß wir sagen können: Beim ganz kleinen Kinde werden alle vier Elemente erfaßt vom Gedanken. — Die spätere Entwickelung besteht gerade darin, daß nur das Luftförmige und Feuerartige vom Gedanken erfaßt wird, denn das ist unser erwachsenes Denken, daß wir die Kraft des Denkens nur eigentlich in unseren fortgesetzten Atmungsprozeß und in unseren den Körper durchwärmenden Prozeß hineinbringen.

Es geht also die Gedankenkraft herauf, möchte ich sagen, von den festeren Partien des physischen Organismus in die luftförmigen, flüchtigen, unschweren Partien des Körpers. Dadurch wird das Denken eben jenes selbständige Element, das uns dann durch das Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode trägt. Und nur wenn wir schlafen, wenn also die auf Erden erworbene Gedankenkraft, die schwächer ist, nicht auf dem Umwege durch Wärme und Luft den physischen Organismus ergreift, dann macht sich im Schlafe auch noch die Fortsetzung der vorirdischen Gedankenkraft geltend. Und so können wir sagen, daß erst dann, wenn der heutige Mensch übergeht zu einer wirklichen Innenbetrachtung des Menschen, seiner selbst, ihm etwas klar wird über die wahre Natur des Denkens. Alle übrige Erkenntnistheorie bleibt eigentlich im Grunde genommen abstraktes Zeug. Wenn man das richtig ins Auge faßt, dann muß man sagen: Es tut sich, wenn man den Vorstellungs-, den Denkprozeß faßt, überall der Ausblick in das vorirdische Dasein auf.

Aber dem mittelalterlichen Denken, das noch eine gewisse Stärke hatte, war verboten worden, zum vorirdischen Dasein zu gehen. Die Präexistenz des Menschen war dogmatisch als Ketzerei erklärt. Nun, was jahrhundertelang der Menschheit aufgedrängt wird, dahinein gewöhnt sich diese Menschheit. Denken Sie sich einmal die Zeit in der Entwickelung der neueren Menschheit bis, sagen wir, 1413. Da ist diese Menschheit durch das Verbot des Denkens an das vorirdische Dasein daran gewöhnt worden, die Gedankenrichtung gar nicht dahin auszubilden, wo sie nach dem vorirdischen Dasein hinkommen könnte. Man hat sich das gründlich abgewöhnt, die Gedankenrichtung nach dem vorirdischen Dasein hin zu orientieren. Wäre bis 1413 der Menschheit nicht verboten gewesen, über das vorirdische Dasein zu denken, dann wäre eine ganz andere Entwickelung heraufgekommen, und wir würden, nicht wahrscheinlich, sondern man kann sogar sagen, ganz gewiß erlebt haben - es ist paradox, wenn ich das ausspreche, aber es ist eben doch eine Wahrheit -: Als, sagen wir, 1858 der Darwinismus auftrat, der äußerlich die Natur in ihrer Entwickelung betrachtete, würde ihm durch die andere Gedankengewöhnung überall, aus allen Naturreichen, der Gedanke des vorirdischen Daseins aufgeleuchtet haben. Er würde eine Naturwissenschaft im Lichte des vorirdischen Daseins des Menschen begründet haben. Statt dessen war der Menschheit abgewöhnt das Hinblicken auf das vorirdische Dasein, und es trat jene Naturwissenschaft auf, die den Menschen, wie ich oftmals ausgesprochen habe, nur als den Schlußpunkt der Tierreihe betrachtete, also gar nicht zu einem vorirdischen, individuellen Leben kommen konnte, weil das Tier eben ein vorirdisches individuelles Leben nicht hat.

So daß man sagen kann: Aus der alten Anschauung vom Sündenfall ist, als der Intellektualismus heraufzudämmern begann, das Gebot geboren worden, nicht von der Präexistenz zu sprechen. Dadurch ist die Naturwissenschaft heraufgediehen direkt als das Kind des mißverstandenen Sündenfalles. Und wir haben eine sündige Naturwissenschaft, wir haben eine Naturwissenschaft, die unmittelbar aus dem Mißverständnisse des Sündenfalles heraus hervorgegangen ist. Das heißt, würde diese Naturwissenschaft bleiben, dann würde die Erde nicht an das Ziel ihrer Entwickelung kommen können, sondern die Menschheit würde ein Bewußtsein entwickeln, das nicht aus der Verbindung mit ihrem göttlich-geistigen Ursprung, sondern aus der Abspaltung vom göttlich-geistigen Ursprung herkommt.

Also wir haben heute tatsächlich nicht nur theoretisch das Reden von den Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis, sondern wir haben positiv, materiell, in dem, was unter dem Einfluß des Intellektualismus sich entwickelt, eben eine schon unter ihr Niveau heruntergesunkene Menschheit. Würde man im Sinne des Mittelalters, das heißt, mit den Worten des Mittelalters sprechen, dann würde man sagen müssen: Die Naturwissenschaft ist dem Teufel verfallen.

Ja, die Historie spricht da ganz merkwürdig. Als die Naturwissenschaft heraufkam mit ihren glänzenden Resultaten, die auch heute nicht etwa von mir angefochten werden sollen, da fürchteten sich die Leute, die noch etwas Empfindung hatten für den wahren Charakter des Menschen, davor, daß die Naturwissenschaft die Menschen dem Teufel nahebringen könnte. Das, was dazumal Furcht und Angst war, was noch im Faust nachdämmert, indem er der Bibel Valet sagt und an die Natur herangeht, das ist die Angst, der Mensch könnte nicht unter dem Zeichen der Sündenerhebung, sondern unter dem Zeichen des Sündenfalles die Erkenntnis der Natur antreten. Die Sache geht wirklich viel tiefer, als man gewöhnlich meint. Und während noch im Anfang des Mittelalters so allerlei traditionelle Empfindungen da waren, in der Furcht, daß sich der teuflische Pudel an die Fersen der Naturforscher heften könne, hat sich in der neueren Zeit die Menschheit die Schlafmütze über den Kopf gezogen und denkt über diese Dinge überhaupt nicht mehr nach.

Das ist die materielle Seite der Sache. Es ist nicht nur ein theoretisches Reden unter dem Einfluß des Sündenfalles in dem Reden von den Grenzen des Naturerkennens vorhanden, sondern es ist der Verfall der Menschheit infolge des Sündenfalles auf intellektualistisch-empirischem Gebiete heute tatsächlich vorhanden. Denn wäre das nicht da, dann hätten wir zum Beispiel nicht eine solche Entwickelungslehre, wie wir sie heute haben, sondern da würde sich durch die gewöhnliche Forschung, die das ja auch in Wirklichkeit ergibt, das Folgende herausgestellt haben: Man hat also, sagen wir Fischtiere, niedere Säugetiere, höhere Säugetiere, Mensch. Heute konstruiert man so annähernd eine Entwickelungslinie, die gerade verläuft. Dafür aber sprechen die Tatsachen gar nicht. Sie werden überall finden: Wo diese Entwickelungslinie gezogen wird, stimmen die Tatsachen nicht.

Die eigentliche naturwissenschaftliche Forschung ist großartig; das, was die Naturforscher über sie sagen, stimmt nicht. Denn würde man die Tatsache unbefangen betrachten, so bekäme man dieses: Mensch, höhere Säugetiere, niedere Säugetiere, Fische. Ich lasse natürlich einzelnes aus. Man kommt also vom Menschen aus in eine Zeit von den höheren, von den niederen Säugetieren und so weiter, bis man zu einer Ursprungsstätte kommt, wo noch alles geistig ist, und an der man sieht, wie der Mensch in seiner weiteren Entwickelung direkt davon abstammt und nach und nach seine höhere Geistigkeit aufgenommen hat, und wie die niedrigeren Wesen eben auch davon abstammen, aber keine höhere Geistigkeit aufgenommen haben. Das ergibt sich unmittelbar aus den Tatsachen. Richtige Anschauungen über diese Tatsache würden wir haben, wenn nicht durch das Verbot, an die Präexistenz, an das vorirdische Dasein zu glauben, die menschlichen Denkgewohnheiten so gelenkt worden wären, daß zum Beispiel ein Geist wie Darwin gar nicht darauf kommen konnte, daß die Sache so sein könnte, wie sie hier dargestellt ist, sondern daß er auf das andere verfallen mußte, eben aus den Denkgewohnheiten heraus, nicht aus der Notwendigkeit der Forschung.

Ebenso wäre es möglich gewesen, in gerader Linie die Goethesche Metamorphosenlehre fortzubilden. Goethe ist ja, wie ich Ihnen immer wieder ausgeführt habe, mit seiner Metamorphosenlehre steckengeblieben. Man betrachte nur unbefangen, wie bei Goethe die Sache aussieht. Er ist steckengeblieben: Er hat die Pflanze betrachtet in ihrer Entwickelung, ist zu der Urpflanze gekommen, ist dann zum Menschen gekommen, hat versucht, am Menschen die Metamorphose der Knochen zu betrachten; da ist er steckengeblieben, völlig steckengeblieben.

Sehen Sie sich doch nur an, was Goethe über die Morphologie des Knochensystems beim Menschen geschrieben hat: genial auf der einen Seite. An einem zerspaltenen Schöpsenschädel, der ihm auffiel am Lido in Venedig, erkannte er, daß die Kopfknochen umgewandelte Wirbelknochen sind. Aber weiter ging es nicht.

Ich habe aufmerksam gemacht auf eine Notiz, die ich während meines Weimarer Aufenthaltes im Goethe-Archiv gefunden habe, wo Goethe darauf hinweist: Das ganze Gehirn des Menschen ist ein umgewandeltes Rückenmarksganglion. Aber weiter ging es wieder nicht. Dieser Satz steht mit Bleistift geschrieben in einem Notizbuch, und man möchte sagen, man sieht es den letzten Bleistiftstrichen dieser Notiz an, wie Goethe unbefriedigt von der Sache war, wie er weiter wollte. Nur war dazu die einzelne Forschung nicht weit genug. Heute ist sie weit genug, sie ist schon lange weit genug, um zu der Frage Stellung zu nehmen. Wenn wir den Menschen von einem noch so frühen Embryonalstadium an betrachten, es kann gar keine Rede davon sein, daß die Form der heutigen Schädelknochen aus den Rückenmarkswirbeln irgendwie hervorgegangen wäre — es kann gar keine Rede davon sein. Wer heutige Embryologie kennt, der weiß: Aus dem, was wir heute am Menschen haben, da fruchtet es nichts, anzunehmen, daß die Schädelknochen umgewandelte Wirbelknochen seien. Deshalb kann man natürlich sagen: Als später Gegenbaur die Sache noch einmal untersuchte, da fand sich für die Schädelknochen, namentlich für die Gesichtsknochen, alles anders, als Goethe vorausgesetzt hatte.

Aber wenn man weiß, daß die heutige Form der Schädelknochen zurückführt auf die Körperknochen des früheren Erdenlebens, dann versteht man die Metamorphose. Da wird man durch die äußere Morphologie selbst hineingetrieben in die Lehre von den wiederholten Erdenleben. Das liegt in der geraden Linie der Goetheschen Metamorphosenlehre. Aber es ist unmöglich, daß diejenige Entwikkelungsströmung, die dann bei Darwin gelandet hat, und die heute noch immer geltend ist in der offiziellen Wissenschaft, zur Wahrheit vordringt. Denn der mißverstandene Sündenfall hat das Denken ruiniert, das Denken in Verfall gebracht. Die Sache ist eben ernster, als man heute geneigt ist zuzugeben.

Man muß eben durchaus sich klar darüber sein, wie sich das Bewußtsein der Menschheit im Laufe der Zeit geändert hat, um solche Dinge, wie ich sie eben jetzt ausgesprochen habe, im richtigen Lichte zu sehen. Wir reden heute davon, daß irgend etwas schön sein könne. Aber wenn Sie heute die Philosophen fragen - und die sollten doch über solche Dinge etwas wissen, nicht wahr, denn dazu sind sie ja da -—, worin die Schönheit besteht, da werden Sie sehen, daß Sie die unglaublichsten Abstraktionen bekommen. «Schön» ist eben ein Wort, das man aus der Empfindung heraus zuweilen instinktmäfßig richtig anwendet. Aber was zum Beispiel ein Grieche sich vorgestellt hat, wenn er in seiner Art vom Schönen gesprochen hat, davon hat man heute ja keine Ahnung. Man weiß nicht einmal, daß der Grieche vom Kosmos gesprochen hat, der für ihn etwas sehr Konkretes war. Unser «Weltall», das ist ein Wort — nun, was in diesem Haufen durcheinanderwirbelt, wenn der Mensch unter dem Einfluß des heutigen Denkens vom Weltall spricht, darüber wollen wir uns lieber heute nicht unterhalten! Der Grieche sprach vom Kosmos. Kosmos ist ein Wort, das Schönheit, Schmückendes, Zierendes, Künstlerisches in sich schließt. Der Grieche wußte: Sobald er von der ganzen Welt spricht, kann er nicht anders, als so von ihr sprechen, daß er sie charakterisiert mit dem Begriff der Schönheit. Kosmos heißt nicht bloß das Weltenall, Kosmos heißt die zur Allschönheit gewordene Naturgesetzmäßigkeit. Das liegt im Worte Kosmos.

Und wenn der Grieche das einzelne schöne Kunstwerk vor sich hatte, oder sagen wir, wenn er den Menschen bilden wollte — wie wollte er ihn bilden, indem er ihn schön bildete? Wenn man noch die Definitionen Platons nimmt, bekommt man ein Gefühl davon, was der Grieche meinte, wenn er den Menschen künstlerisch darstellen wollte. In dem Worte, das er dafür prägte, liegt ungefähr das: Hier auf Erden ist der Mensch gar nicht das, was er sein soll. Er stammt vom Himmel, und ich habe ihn in seiner Form so dargestellt, daß man ihm seinen himmlischen Ursprung ansieht. — Wie wenn er vom Himmel heruntergefallen wäre, so etwa stellte der Grieche sich den Menschen als schön vor, wie wenn er eben vom Himmel gekommen wäre, wo er natürlich ganz anders ist, als die Menschen in ihrer äußeren Gestalt. Die sehen nicht so aus, als ob sie eben vom Himmel heruntergefallen wären, die haben das Kainszeichen des Sündenfalles überall in ihrer Form. Das ist griechische Vorstellung. Wir dürfen uns so etwas gar nicht gestatten in unserer Zeit, wo wir eben den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem vorirdischen, das heißt, mit dem himmlischen Dasein vergessen haben. So daß man sagen kann, bei den Griechen heißt schön = seine himmlische Bedeutung offenbarend. Da wird der Schönheitsbegriff konkret. Sehen Sie, bei uns ist er abstrakt.

Ja, es hat einen interessanten Streit gegeben zwischen zwei Ästhetikern, dem sogenannten V-Vischer - weil er sich mit V schrieb -, dem Schwaben-Vischer, einem sehr geistreichen Manne, der eine außerordentlich bedeutende Ästhetik, bedeutend im Sinne unseres Zeitalters, geschrieben hat, und dem Formalisten Robert Zimmermann, der eine andere Ästhetik geschrieben hat. Der eine, VVischer, definiert das Schöne als die Offenbarung der Idee in der sinnlichen Form. Zimmermann definiert das Schöne als das Zusammenstimmen der Teile in einem Ganzen, also der Form nach; Vischer mehr dem Inhalte nach.

Eigentlich sind diese Definitionen alle wie jene berühmte Gestalt, die sich an ihrem eigenen Haarschopf immer wieder in die Höhe zieht. Denn wenn einer sagt: Das Erscheinen der Idee in der sinnlichen Form - ja, was ist die Idee? Da müßte man erst etwas haben, was die Idee ist. Denn der Gedankenleichnam, den die Menschheit als Idee hat, wenn der in sinnlicher Form erscheint -, ja, da wird nichts daraus! Aber das heißt etwas, wenn man im griechischen Sinne fragt: Was ist ein schöner Mensch? - Ein schöner Mensch ist derjenige, der die Menschengestalt so idealisiert enthält, daß er einem Gotte ähnlich sieht — das ist im Griechischen ein schöner Mensch. Da kann man etwas anfangen mit einer solchen Definition, da hat man etwas in einer solchen Definition.

Darum handelt es sich, daß man sich bewußt wird, wie der Bewußtseinsinhalt, die Seelenverfassung der Menschen im Laufe der Zeit sich geändert hat. Der moderne Mensch glaubt ja, der Grieche hätte ebenso gedacht, wie man heute denkt. Und wenn wirklich heute Geschichten der griechischen Philosophie geschrieben werden, so ist es ja so: zum Beispiel wenn Zeller eine ausgezeichnete Geschichte der griechischen Philosophie schreibt - im Sinne des heutigen Zeitalters ist sie ausgezeichnet -, da ist es so, wie wenn Platon nicht in der Platonischen Akademie, sondern im 19. Jahrhundert gelehrt hätte, so wie Zeller selbst an der Berliner Universität gelehrt hat. Sobald man den Gedanken konkret faßt, sieht man ihm seine Unmöglichkeit an, denn Platon hätte selbstverständlich im 19. Jahrhundert nicht an der Berliner Universität lehren können, das wäre ja nicht gegangen. Aber was von ihm überliefert ist, das übersetzt man dann in die Begriffe des 19. Jahrhunderts und hat gar kein Gefühl dafür, daß man ja zurückgehen muß mit seiner ganzen Seelenverfassung in ein anderes Zeitalter, wenn man Platon wirklich treffen will.

Wenn man dann sich ein Bewußtsein dafür aneignet, wie die Dinge in der Seelenverfassung des Menschen geworden sind, dann wird man es nicht mehr so absurd finden, wenn man sagt: Eigentlich ist, mit Bezug auf sein Denken über die äußere Natur und über den Menschen selbst, der Mensch dem Sündenfall ganz verfallen.

Und da muß an etwas gedacht werden, an das die heutigen Menschen nicht denken, ja, das sie vielleicht sogar als etwas verdreht betrachten. Es muß davon gesprochen werden, daß in der theoretischen Erkenntnis von heute, die populär geworden ist und alle Köpfe bis in die letzten Winkel der Welt, bis in die letzten Dörfer heute beherrscht, etwas lebt, was erst durch Christus erlöst werden muß. Es muß erst das Christentum verstanden werden auf diesem Gebiet.

Nun, wenn man heute einem naturwissenschaftlichen Denker zumuten würde, er müsse begreifen, daß sein Denken durch Christus erlöst werden muß, ja, dann wird er sich an den Kopf greifen und sagen: Die Tat des Christus mag für alles mögliche geschehen sein in der Welt, aber zur Erlösung von dem Sündenfall der Naturwissenschaft — dazu lassen wir uns nicht herbei! - Aber auch wenn Theologen naturwissenschaftliche Bücher schreiben, wie sie es ja im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert zahlreich getan haben, die einen über Ameisen, die andern über anderes, über das Gehirn und so weiter -, und diese Bücher sind sogar meistens ausgezeichnet, besser als von Naturforschern, weil diese Leute in etwas lesbarerer Form schreiben können -, aber auch dann atmen diese auf dem wissenschaftlichen Felde geschriebenen Bücher erst recht das Bedürfnis: hier muß Ernst gemacht werden mit einer wahren Christologie, das heißt, wir brauchen heute gerade auf intellektualistischem Gebiete eine wirkliche Sündenerhebung, die dem Sündenfall entgegentreten muß.

So sehen wir auf der einen Seite, daß der Intellektualismus angefressen ist von dem, was entstanden ist aus dem mißverständlichen Sündenbewußtsein, nicht aus der Tatsache des Sündenfalles, sondern aus dem mitßverständlichen Sündenbewußtsein. Denn das unmißverständliche Sündenbewußtsein muß eben den Christus als ein höheres Wesen in den Mittelpunkt der Erdenentwickelung stellen und von da aus den Weg herausfinden aus dem Sündenfall. Dazu bedarf es einer tieferen Einzelbetrachtung der menschlichen Entwickelung auch auf geistigem Gebiete.

Wenn man, so wie es heute gewöhnlich geschieht, die mittelalterliche Scholastik betrachtet, bis meinetwillen selbst zu Augustinus zurück, so kann ja daraus gar nichts folgen. Es kann nichts daraus folgen, weil man nichts anderes sieht, als daß sich nun gewissermaßen das moderne naturwissenschaftliche Bewußtsein weiterentwikkelt, aber man läßt außer acht das Höhere, das Übergreifende.

Nun habe ich hier einmal in diesem Saale versucht, die mittelalterliche Scholastik darzustellen, so daß man die ganzen Zusammenhänge sehen kann. Ich habe hier einmal über den Thomismus und was damit zusammenhängt, einen kleinen Zyklus gehalten. Aber das ist ja gerade das Schmerzliche, was unserer anthroposophischen

Bewegung so wenig förderlich ist, daß solche Anregungen gar nicht aufgegriffen werden, daß der Zusammenhang des heutigen glänzenden naturwissenschaftlichen Zustandes mit dem, was nun hineinfahren muß in die Naturwissenschaften, eben nicht gesucht wird! Und wenn das nicht gesucht wird, dann müßten unsere wirklich mit großen Opfern errungenen Forschungsinstitute unfruchtbar bleiben. Bei denen würde es sich darum handeln, solche Anregungen wirklich zu benützen, um vorwärtszukommen, nicht sich in unfruchtbare Polemiken über den Atomismus einzulassen.

Unsere Naturwissenschaft ist heute in ihrem Tatsachengebiete überall so weit, daß sie danach drängt, endlich jene sterilen Denkereien zu verlassen, die wir heute in den naturwissenschaftlichen Büchern haben. Man kennt ja den Menschen anatomisch, physiologisch genug, um, wenn man die richtigen Denkmethoden wählt, selbst zu solchen heute noch kühn erscheinenden Folgerungen kommen zu können wie von der Metamorphose der Kopfesform aus der Körperform im früheren Leben. Aber natürlich, wenn man am Materiellen haftet, dann kann man nicht dazu kommen, denn dann fragt man in sehr geistreicher Weise: Ja, dann müßten ja die Knochen materiell bleiben, daß sie sich materiell nach und nach im Grabe umwandeln können. — Es handelt sich eben darum, daß die materielle Form eine äußerliche Form ist und daß die Formkräfte der Metamorphose unterliegen.

Auf der einen Seite wurde das Denken dadurch in Fesseln geschlagen, daß auf die Präexistenz die Finsternis geworfen worden ist. Auf der andern Seite handelt es sich um die Postexistenz, um das Leben nach dem Tode. Das Leben nach dem Tode kann aber durch keine andere Erkenntnis errungen werden als durch eine übersinnliche Erkenntnis. Weist man die übersinnliche Erkenntnis zurück, dann bleibt das Leben nach dem Tode ein Glaubensartikel, der auf Autorität hin bloß geglaubt werden kann. Ein richtiges Verständnis des Denkprozesses führt zum präexistenten Leben, wenn darüber zu denken nicht verboten ist. Das postexistente Leben kann aber nur durch übersinnliche Erkenntnis eben Erkenntnis werden. Da muß jene Methode eintreten, die ich in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» beschrieben habe. Diese aber wiederum verpönt man aus dem heutigen Zeitbewußtsein heraus.

Und so wirken zwei Dinge zusammen: auf der einen Seite die Fortwirkung des Verbotes, an das präexistente Leben des Menschen heranzugehen, auf der andern Seite das Perhorreszieren der übersinnlichen Erkenntnis. Wenn man beides zusammenbringt, dann bleibt alle übersinnliche Welt die Domäne einer Nichterkenntnis, nämlich des bloßen Glaubens, und dann bleibt das Christentum eine Sache des Glaubens, nicht der Erkenntnis. Und dann läßt sich diejenige Wissenschaft, die «Wissenschaft» sein will, nicht herbei, mit dem Christus überhaupt etwas zu tun haben zu wollen. Und dann haben wir den heutigen Zustand.

Aber ich sagte schon im Eingange der heutigen Betrachtungen: In bezug auf das Bewußtsein, das heute ganz vom Intellektualismus angefüllt ist, ist die Menschheit den Folgen des Sündenfalles verfallen und wird sich nicht erheben können, das heißt, das Erdenziel nicht erreichen können. Mit der heutigen Wissenschaftlichkeit laßt sich das Erdenziel nicht erreichen. Aber der Mensch ist in den Tiefen seiner Seele eben trotzdem heute noch ungebrochen. Holt er diese Tiefen seiner Seele heraus, entwickelt er übersinnliche Erkenntnis im Sinne des Christus-Impulses, dann kommt er dadurch auch wiederum für das intellektuelle Gebiet zur Erlösung von dem heutigen, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, der Sünde verfallenen Intellektualismus.

Das erste also, was notwendig ist, das ist, einzusehen, daß durchdrungen werden muß gerade das intellektuell empirische Forschen mit demjenigen, was aus der Geistigkeit der Welt heraus erfaßt werden kann. Also die Wissenschaft muß durchdrungen werden mit der Geistigkeit. Aber diese Geistigkeit kann nicht an den Menschen herankommen, wenn nur immer dasjenige, was im Raume nebeneinander ist, nach seinem Nebeneinander untersucht wird, oder was in der Zeit aufeinanderfolgt, nach seinem Nacheinander.

Wenn Sie die Form des menschlichen Hauptes, namentlich in bezug auf seinen Knochenbau, untersuchen und ihn nur mit dem übrigen Knochenbau vergleichen: Röhrenknochen, Wirbelknochen, Rippenknochen mit Kopfknochen — dann kommen Sie eben auf nichts. Sie müssen über Raum und Zeit hinausgehen zu jenen Begriffen, die hier in der Geisteswissenschaft entwickelt werden, indem man von Erdendasein zu Erdendasein den Menschen erfaßt. Also Sie müssen sich klar sein darüber: Wenn heute die Kopfknochen angesehen werden, so kann man sie ansehen als verwandelte Wirbelknochen. Aber dasjenige, was Rückenmarkswirbel heute am Menschen sind, das verwandelt sich nie in Kopfknochen in dem Bereich des Erdendaseins; die müssen erst verfallen, müssen erst ins Geistige umgewandelt werden, um in einem nächsten Erdenleben zu Kopfknochen werden zu können.

Wenn dann ein instinktiv-intuitiver Geist kommt wie Goethe, so sieht er das den Formen der Kopfknochen an, daß sie umgewandelte Wirbelknochen sind. Aber um von dieser Anschauung zu den Tatsachen zu kommen, dazu braucht man Geisteswissenschaft. Goethes Metamorphosenlehre gewinnt überhaupt erst innerhalb der Geisteswissenschaft einen Sinn. Sie hat keinen Sinn ohne die Geisteswissenschaft. Daher war sie für Goethe selber in ihrem letzten Ende unbefriedigend. Aber deshalb sind es auch allein diese Erkenntnisse, die mit anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft zusammenhängen, die den Menschen in ein rechtes Verhältnis bringen zwischen Sündenfall und Sündenerhebung. Daher sind diese anthroposophischen Erkenntnisse heute etwas, was sich nicht bloß in der Betrachtung, sondern als Lebensgehalt lebendig in die Menschenentwickelung hineinstellen will.

Tenth Lecture

In the last lectures I have spoken here of the Fall and the elevation of sin, and have described the elevation of sin as something that must be recognized in the general consciousness of mankind in the present epoch as a kind of ideal for human striving and human volition. Now I have emphasized more the formal side of the Fall, as it still manifests itself in our time, by pointing out how the Fall plays into intellectual life. What is said about the limits of the knowledge of nature has basically arisen from the view that man does not have the inner strength to reach the spiritual, that he should therefore not aspire to an elevation from the contemplation of the earthly. And I said: When people today speak of the limits of the knowledge of nature, this is actually only the modern intellectual way of speaking of man's oppression by sin, which was common in older times and especially throughout medieval civilization. Today I would like to speak more of the material side of the matter and point out how mankind of today, if it remains with the views that have arisen in the course of recent development, preferably in the course of intellectualistic development, cannot reach the goal on earth at all. For the general consciousness of today has to a certain extent already become a slave to the Fall itself through the consciousness of the Fall. Intellectualism today already has the character of decay, and such a strong decay at that, that if intellectualist culture remains as it is at present, there can be no talk of humanity reaching its goal on earth. Today it is necessary to know that in the depths of the human souls there are still forces at work that are, in a sense, better than the culture of consciousness that has taken hold to this day.

In order to understand this, it is necessary to clearly visualize the character of this culture of consciousness. This culture of consciousness has arisen on the one hand from a certain conception of the thinking human being, and on the other hand from a certain conception of the willing human being. The feeling man lies in between, and one also considers the feeling man when one considers the thinking man on the one hand and the willing man on the other. Nowadays mankind only uses its thinking to get to know the outer realms of nature to the widest possible extent and also to understand human life in the sense of the way of thinking we are accustomed to from the customary view of nature. Today we learn to think from the natural sciences and then also view social life with this way of thinking, which we have learned from the natural sciences as they are customary today.

Now people often believe that this perception of the thinking person, of the person who looks at nature in a thinking way, is unbiased. People talk about all sorts of things, about the unconditionality of science and the like. But I have often emphasized that this lack of presuppositions is not far off. For everything that the thinker applies today when he devotes himself to scientific investigations, which the rest of humanity then follows in its life, has developed out of earlier ways of thinking. In fact, modern thinking has developed entirely out of medieval thinking. Even what is said today - and I have already emphasized this - by opponents of medieval thinking is thought with the methods of thinking that themselves developed out of medieval thinking. And an essential character of medieval thinking has entered into today's thinking by the fact that thinking itself is actually only considered according to how it applies itself to external nature, that the thought process is actually not considered at all, that one does not devote oneself to any view that goes to the consideration of thinking itself. One takes no notice of thinking itself, in its inner vitality.

This happens for a reason that emerges from my reflections presented here. I once said here: The thoughts that modern man has about nature are actually corpses of thought. When we think about the realms of nature, we think in corpses of thought, for the life of these corpses of thought falls into the pre-earthly existence of man. The thoughts we develop today about the realms of nature and also about the life of man are dead when we think, but they were alive in our pre-earthly existence.

In our pre-earthly existence, before we descended into the physical embodiment on earth, the abstract, dead thoughts that we develop here on earth today according to the customs of our age were alive, elemental, living entities. Then we lived in these thoughts as living entities, just as we live in our blood here on earth today. Now, here on earth, these thoughts have died and become abstract. But only as long as we stop to consider our thinking in its application to external nature is it dead. As soon as we look into ourselves, it reveals itself to us as living, for there within ourselves it continues to work, albeit in a way that is unconscious to the ordinary consciousness of today. That which was present in our pre-earthly existence continues to work there. For it is the forces of these living thoughts that take possession of our physical organism during our incarnation on earth. It is the power of these living pre-earthly thoughts that makes us grow, that forms our organs. So that today, for example, when the usual epistemologists speak of thinking, they speak of something dead. For if they wanted to speak of the true nature of thought, not of its corpse, they would have to realize that they would have to look within, and inwardly they would notice that there is no independence of that which began with the birth or conception of man on earth, but that in this inward working of thought the living power of pre-earthly thought continues.

Even if we only look at the still very small child - I do not want to take the human germ in the mother's body into consideration today - even in the small child, which still leads its dreamlike slumbering earth life, we still see in what grows in the child, even in what rages in the child, the living power of pre-earthly thinking, if we are able to recognize what really presents itself. And we then become aware of the reason why the child is actually still slumbering like a dream and only later begins to have thoughts. This is due to the fact that in the first period of a small child's life, when it is still slumbering like a dream, its whole organism is seized by thoughts. But when the organism gradually solidifies within itself, then the earthy and watery parts of the organism are no longer strongly seized by thought, but only the airy and fiery, the warmth-like parts. So that we can say: In the very young child all four elements are grasped by thought. - The later development consists precisely in the fact that only the airy and fiery is grasped by thought, for that is our adult thinking, that we only actually bring the power of thought into our continuing breathing process and into our body-warming process.

So the power of thought goes up, I would say, from the more solid parts of the physical organism into the airy, volatile, non-heavy parts of the body. Thus thinking becomes the independent element that carries us through life between birth and death. And only when we sleep, that is, when the power of thought acquired on earth, which is weaker, does not take hold of the physical organism in a roundabout way through warmth and air, does the continuation of the pre-earthly power of thought also assert itself in sleep. And so we can say that only when the man of today passes over to a real inner contemplation of man, of himself, does something become clear to him about the true nature of thought. All other epistemology actually remains basically abstract stuff. If one considers this correctly, then one must say: if one grasps the process of imagination, the process of thinking, the view into the pre-earthly existence opens up everywhere.

But medieval thinking, which still had a certain strength, was forbidden to go to the pre-earthly existence. The pre-existence of man was dogmatically declared to be heresy. Now, what has been imposed on mankind for centuries, mankind becomes accustomed to. Just think of the time in the development of modern humanity up to, say, 1413, when, through the prohibition of thinking about the pre-earthly existence, this humanity became accustomed to not developing the direction of thought to where it could go after the pre-earthly existence. They have thoroughly gotten out of the habit of orienting the direction of thought towards the pre-earthly existence. If up to 1413 mankind had not been forbidden to think about the pre-earthly existence, then a quite different development would have come about, and we would, not probably, but one can even say, quite certainly have experienced - it is paradoxical when I say this, but it is nevertheless a truth -: When, let us say, Darwinism appeared in 1858, which outwardly looked at nature in its development, the thought of the pre-earthly existence would have lit up for it everywhere, from all kingdoms of nature, through the different habit of thought. He would have founded a natural science in the light of man's pre-earthly existence. Instead of this, mankind had become accustomed to looking at the pre-earthly existence, and that natural science arose which, as I have often said, regarded man only as the end of the animal series, and therefore could not come to a pre-earthly, individual life, because the animal does not have a pre-earthly individual life.

So that one can say: From the old view of the Fall of Man, when intellectualism began to dawn, the commandment was born not to speak of pre-existence. As a result, natural science emerged directly as the child of the misunderstood Fall of Man. And we have a sinful natural science, we have a natural science that has emerged directly from the misunderstanding of the Fall. This means that if this natural science were to remain, then the earth would not be able to reach the goal of its development, but humanity would develop a consciousness that does not come from the connection with its divine-spiritual origin, but from the separation from the divine-spiritual origin.

So today we actually have not only theoretical talk of the limits of knowledge of nature, but we have positively, materially, in what is developing under the influence of intellectualism, a humanity that has already sunk below its level. If one were to speak in the sense of the Middle Ages, that is, with the words of the Middle Ages, then one would have to say: Natural science has fallen to the devil.

Yes, history speaks quite strangely. When natural science emerged with its brilliant results, which I do not wish to dispute today, people who still had some feeling for the true character of man were afraid that natural science might bring people close to the devil. That which was then fear and anxiety, which still lingers in Faust as he says farewell to the Bible and approaches nature, is the fear that man might come to the knowledge of nature not under the sign of the elevation of sin, but under the sign of the fall of man. The matter really goes much deeper than is usually thought. And while at the beginning of the Middle Ages there were still all kinds of traditional sentiments, in the fear that the devilish poodle could attach itself to the heels of natural scientists, in more recent times mankind has pulled its sleeping cap over its head and no longer thinks about these things at all.

This is the material side of the matter. Not only is there theoretical talk under the influence of the Fall in the talk of the limits of the knowledge of nature, but the decline of mankind as a result of the Fall in the intellectual-empirical field is actually present today. For if this were not the case, then we would not have, for example, the theory of evolution that we have today, but the following would have emerged through ordinary research, which in reality also reveals the following: We have, say, fish animals, lower mammals, higher mammals, man. Today we construct an approximate line of development that runs in a straight line. But the facts do not support this at all. You will find it everywhere: Wherever this line of development is drawn, the facts are not correct.

The actual scientific research is great; what the natural scientists say about it is not true. For if one were to look at the facts impartially, one would get this: Man, higher mammals, lower mammals, fish. Of course, I'm leaving out some of them. So one comes from man into a time of the higher mammals, of the lower mammals and so on, until one comes to a place of origin where everything is still spiritual, and where one sees how man in his further development descends directly from it and has gradually absorbed its higher spirituality, and how the lower beings also descend from it, but have not absorbed any higher spirituality. This follows directly from the facts. We would have a correct view of this fact if the prohibition of believing in pre-existence, in pre-earthly existence, had not directed human habits of thought in such a way that, for example, a mind like Darwin could not come to the conclusion that the matter could be as it is presented here, but that he had to fall back on the other, precisely out of the habits of thought, not out of the necessity of research.

It would also have been possible to develop Goethe's theory of metamorphosis in a straight line. As I have repeatedly explained to you, Goethe got stuck with his theory of metamorphosis. Just take an impartial look at how things look with Goethe. He got stuck: He looked at the plant in its development, came to the primordial plant, then came to man, tried to look at the metamorphosis of bones in man; there he got stuck, completely stuck.

Just look at what Goethe wrote about the morphology of the bone system in humans: brilliant on the one hand. From a split skull he noticed on the Lido in Venice, he recognized that the head bones are transformed vertebral bones. But that was as far as it went.

I drew attention to a note that I found in the Goethe Archive during my stay in Weimar, where Goethe refers to this: The entire human brain is a transformed spinal cord ganglion. But that was as far as it went. This sentence is written in pencil in a notebook, and you could say that you can see from the last pencil strokes of this note how Goethe was unsatisfied with the matter, how he wanted to continue. But individual research was not far enough along. Today it is far enough, it has been far enough for a long time, to take a stand on the question. If we look at the human being from an early embryonic stage, there can be no question of the shape of today's skull bones having somehow emerged from the spinal cord vertebrae - there can be no question of that. Anyone familiar with modern embryology knows that from what we have in humans today, it is useless to assume that the skull bones are transformed vertebral bones. Therefore, one can of course say that when Gegenbaur later re-examined the matter, everything was found to be different for the skull bones, especially the facial bones, than Goethe had assumed.

But if one knows that the present form of the skull bones leads back to the body bones of the earlier life on earth, then one understands the metamorphosis. Through the external morphology itself one is driven into the doctrine of repeated earth lives. This lies in the straight line of Goethe's theory of metamorphosis. But it is impossible that the current of development which then ended up with Darwin, and which is still valid today in official science, should penetrate to the truth. For the misunderstood Fall of Man has ruined thinking, brought thinking into decay. The matter is more serious than one is inclined to admit today.

One must be quite clear about how the consciousness of mankind has changed in the course of time in order to see such things as I have just said in the right light. Today we talk about anything being beautiful. But if you ask the philosophers today - and they should know something about such things, shouldn't they, because that's what they're there for - what beauty consists of, you'll see that you get the most incredible abstractions. “Beautiful” is just a word that one sometimes uses correctly out of instinct. But today we have no idea what a Greek, for example, had in mind when he spoke of beauty in his own way. We don't even know that the Greek spoke of the cosmos, which for him was something very concrete. Our “universe”, that's a word - well, we'd rather not talk about what gets mixed up in this heap when people speak of the universe under the influence of today's thinking! The Greek spoke of the cosmos. Cosmos is a word that includes beauty, adornment, decoration, artistry. The Greek knew that as soon as he spoke of the whole world, he could only speak of it in such a way that he characterized it with the concept of beauty. Cosmos does not merely mean the universe, cosmos means the lawfulness of nature that has become universal beauty. This lies in the word cosmos.

And if the Greek had the individual beautiful work of art in mind, or let us say, if he wanted to form man - how did he want to form him by making him beautiful? If we take Plato's definitions, we get a sense of what the Greek meant when he wanted to represent man artistically. The word he coined for this is something like this: Here on earth, man is not what he is supposed to be. He comes from heaven, and I have depicted him in his form in such a way that one can see his heavenly origin. - As if he had fallen from heaven, the Greek imagined man as beautiful, as if he had just come from heaven, where he is naturally quite different from man in his outer form. They do not look as if they had just fallen from heaven, they have the mark of Cain's fall everywhere in their form. That is Greek imagination. We must not allow ourselves such a thing in our time, when we have forgotten the connection of man with the pre-earthly, that is, with the heavenly existence. So that one can say that for the Greeks, beautiful = revealing its heavenly meaning. There the concept of beauty becomes concrete. You see, with us it is abstract.

Yes, there was an interesting dispute between two aestheticians, the so-called V-Vischer - because he wrote with a V - the Swabian Vischer, a very witty man who wrote an extraordinarily important aesthetic, important in the sense of our age, and the formalist Robert Zimmermann, who wrote a different aesthetic. The one, VVischer, defines beauty as the revelation of the idea in sensual form. Zimmermann defines beauty as the harmony of the parts in a whole, i.e. in terms of form; Vischer more in terms of content.

In fact, these definitions are all like that famous figure who keeps pulling herself up by her own hair. For when someone says: The appearance of the idea in sensual form - yes, what is the idea? One would first have to have something that is the idea. For the corpse of thought which mankind has as an idea, if it appears in sensuous form - yes, nothing will come of it! But that means something if you ask in the Greek sense: What is a beautiful person? - A beautiful person is one who contains the human form in such an idealized way that he resembles a god - that is a beautiful person in Greek. You can do something with such a definition, you have something in such a definition.