World History in the Light of Anthroposophy

and as a Foundation for Knowledge of the Human Spirit

GA 233

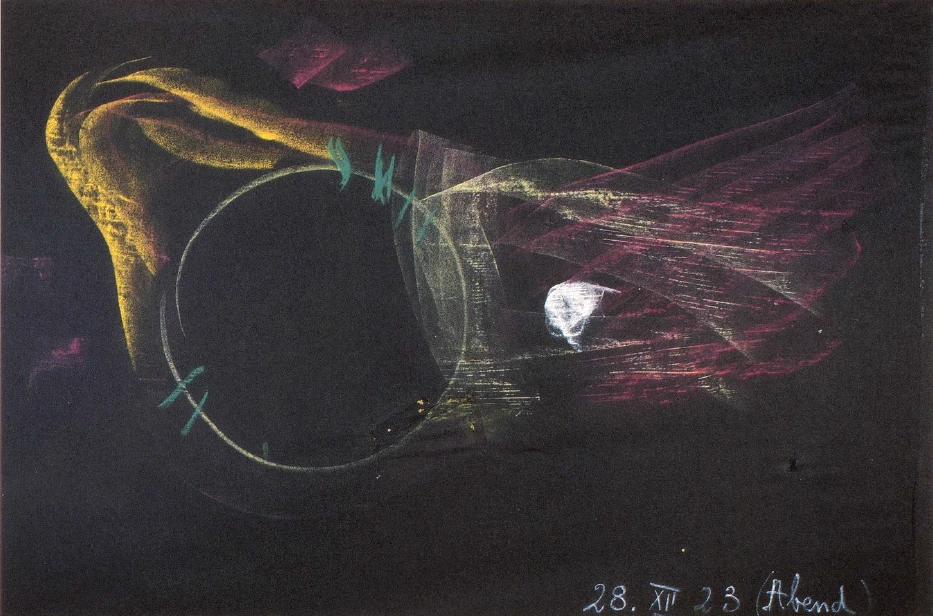

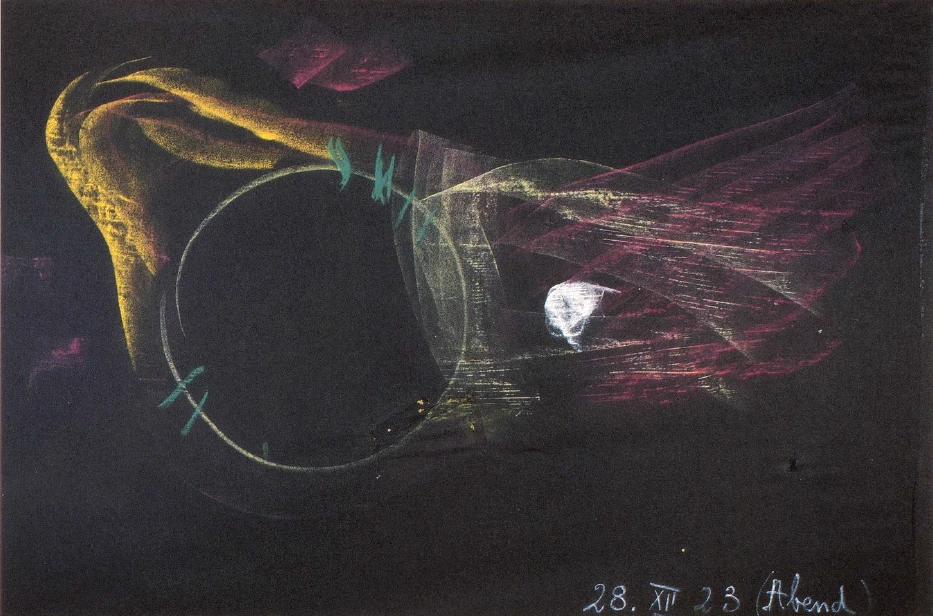

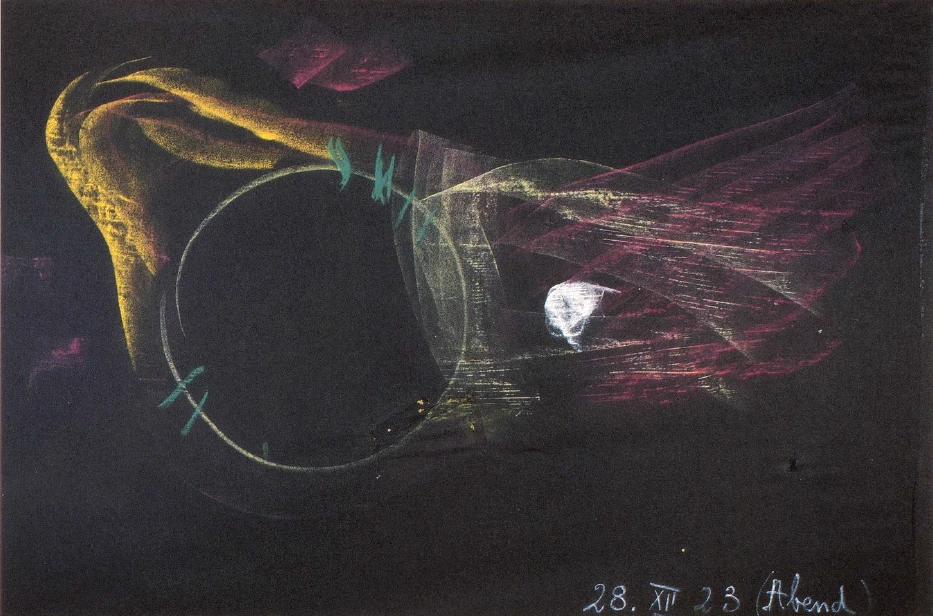

28 December 1923, Dornach

Lecture V

Among the mysteries of ancient times Ephesus holds a unique position. You will remember that in considering the part played by Alexander in the evolution of the West, I had to mention also this Mystery of Ephesus. Let us try to see wherein lies the peculiar importance of this Mystery.

We can only grasp the significance of the events of earlier and of more recent times when we understand and appreciate the great change that took place in the character of the Mysteries (which were in reality the source whence all the older civilisations sprang) in passing from the East to the West, and, in the first place, to Greece. This change was of the following nature.

When we look back into the older Mysteries of the East, we have everywhere the impression: The priests of the Mysteries are able, from their own vision, to reveal great and important truths to their pupils. The farther back we go in time, the more are these Wise Men or Priests in a position to call forth in the Mysteries the immediate presence of the Gods themselves, the Spiritual Beings who guide the worlds of the planets, who guide the events and phenomena of Earth. The Gods were actually there present.

The connection of the human being with the macrocosm was revealed in many different Mysteries in an equally sublime manner to that I pictured for you yesterday, in connection with the Mysteries of Hibernia and also with the teachings that Aristotle had still to give to Alexander the Great. An outstanding characteristic of all ancient Oriental Mysteries was that moral impulses were not sharply distinguished from natural impulses. When Aristotle points Alexander to the North-West, where the Spirits of the element of Water held dominion, it was not only a physical impulse that came from that quarter—as we to-day feel how the wind blows from the North-West and so forth—but with the physical came also moral impulses. The physical and the moral were one. This was possible, because through the knowledge that was given in these Mysteries—the Spirit of Nature was actually perceived in the Mysteries—man felt himself one with the whole of Nature. Here we have something in the relation of man to Nature, that was still living and present in the time that intervened between the life of Gilgamesh and the life of the individuality Gilgamesh became, who was also in close contact with the Mysteries, namely, with the Mystery of Ephesus. There was still alive in men of that time a vision and perception of the connection of the human being with the Spirit of Nature. This connection they perceived in the following way. Through all that the human being learned concerning the working of the elementary spirits in Nature, and the working of the Beings of Intelligence in the planetary processes, he was led to this conclusion: All around me I see displayed on every side the plant-world—the green shoots, the buds and blossoms and then the fruit. I see the annual plants in the meadows and on the country-side, that grow up in Spring-time and fade away again in Autumn. I see, too, the trees that go on growing for hundreds of years, forming a bark on the outside, hardening to wood and reaching downwards far and wide into the Earth with their roots. But all that I see out there—the annual herbs and flowers, the trees that take firm hold into the Earth—once upon a time, I, as man, have borne it all within me.

You know how to-day, when there is carbonic acid in the air, that has come about through the breathing of human beings, we can feel that we ourselves have breathed out the carbonic acid, we have breathed it into space. We have therefore still to-day this slight connection with the Cosmos. Through the airy part of our nature, through the air that gives rise to the breathing and other air-processes that go on in the human organism, we have a living connection with the great Universe, with the Macrocosm. The human being to-day can look upon his out-breathed breath, upon the carbonic acid that was in him and is now outside him. But just as we are able to-day to look upon the carbonic acid we have breathed out—we do not generally do so, but we could—so did the initiates of olden times look upon the whole plant-world. Those who had been initiated in the Oriental Mysteries, or had received the wisdom that streamed forth from the Oriental Mysteries, were able to say: I look back in the evolution of the world to an ancient Sun epoch. In that time I bore still within me the plants. Then afterwards I let them stream forth from me into the far circles of Earth existence. But as long as I bore the plants within me, while I was still that Adam Cadmon who embraced the whole Earth and the plant-world with it, so long was this whole plant-world watery-airy in substance. Then the human being separated off from himself this plant-world. Imagine that you were to become as big as the whole Earth, and then to separate off, to secrete, as it were, inwardly something plant-like in nature, and this plant-like substance were to go through metamorphoses in the watery element—coming to life, fading away, growing up, being changed, taking on different shapes and forms—and you will by this imagination call up again in your soul feelings and experiences that once lived in it. Those who received their education and training in the East at about the time of Gilgamesh were able to say to themselves that these things had once been so.

And when they looked abroad upon the meadows and beheld all the growth of green and flowers, then they said: We have separated the plants from ourselves, we have put them forth from us in an earlier stage of our evolution; and the Earth has received them. The Earth it is that has lent them root, and has given them their woody nature; the tree-nature in the world of plants comes from the Earth. But the whole plant-nature as such has been cast off, as it were, by the human being, and received by the Earth. In this way man felt an intimate and near relationship with everything of a plant-nature.

With the higher animals the human being did not feel a relationship of this kind. For he knew that he could only work his way rightly and come to his true place on the Earth by overcoming the animal form, by leaving the animals behind him in his evolution. The plants he took with him as far as the Earth; then gave them over to her that she might receive them into her bosom. For the plants he was upon Earth the Mediator of the Gods, the Mediator between the Gods and the Earth.

Men who had this great experience acquired a feeling that may be put quite simply in a few words. The human being comes hither to the Earth from the World-All. The question of number does not come into consideration; for, as I said yesterday, they were all and each within the other. That which afterwards becomes the plant-world separates off from man, the Earth receives it and gives it root. The human being felt as though he had folded the Earth about with a garment of plant growth, and as though the Earth were thankful for this enfolding and took from him the watery-airy plant element that he was able, as it were, to breathe on to her.

In entering into this experience men felt themselves intimately associated with the God, with the chief God of Mercury. Through the feeling: We have ourselves brought the plants on to the Earth, men came into a special relation with the God Mercury.

Towards the animals, on the other hand, man had a different feeling. He knew that he could not bring them with him to Earth, he had to cast them off, he had to make himself free from them, otherwise he would not be able to evolve his human form in the right way. He thrust the animals from him; they were pushed out of the way and had then to go through an evolution on their own account on a lower level than the level of humanity. Thus did the man of olden times—of the Gilgamesh time and later—feel himself placed between the animal kingdom and the plant kingdom. In relation to the plant kingdom he was the bearer, who bore the seed to the Earth and fructified the Earth with it, doing this as Mediator for the Gods. In relation to the animal kingdom he felt as though he had pushed it away from him, in order that he might become man without the encumbrance of the animals, who have consequently been stunted and retarded in their development.

The whole animal-worship of Egypt has to do with this perception. The deep fellow-feeling, too, with animals that we find in Asia is connected with it. It was a sublime conception of Nature that man had, feeling his relationship on the one hand with the plant world and on the other hand with the world of animals. In relation to the animal he had a feeling of emancipation. In relation to the plant he felt a near and intimate kinship. The plant world was to him a bit of himself, and he felt a sincere love for the Earth inasmuch as the Earth had received into herself the bit of humanity that gave rise to the plants, had let these take root in her, had even given of her own substance to clothe the trees in bark. There was always a moral element present when man took cognisance of the physical world around him. When he beheld the plants in the meadow, it was not only the natural growth that he perceived. In this growth he perceived and felt a moral relation to man. With the animal man felt again another moral relation: he had fought his way up beyond them.

Thus we find in the Mysteries over in the East a sublime conception of Nature and of Spirit in Nature. Later there were Mysteries in Greece, too, but with a much less real perception of Nature and of Spirit in Nature. The Greek Mysteries are grand and sublime, but they are essentially different from the Oriental Mysteries. It is characteristic of these that they do not tend to make man feel himself on the Earth, but that through them man feels himself a part of the Cosmos, a part of the World-All. In Greece, on the other hand, the character of the Mysteries had changed and the time was come when man began to feel himself united with the Earth. In the East the spiritual world itself was either seen or felt in the Mysteries. It is absolutely true to say that in the ancient Oriental Mysteries the Gods themselves appeared among the priests, who did sacrifice there and made prayers. The Mystery Temples were at the same time the earthly Guest Houses of the Gods, where the Gods bestowed upon men through the priests what they had to give them from the treasures of Heaven. In the Greek Mysteries appeared rather the images of the Gods, the pictures, as it were, the phantoms,—true and genuine, but phantoms none the less; no longer the Divine Beings, no longer the Realities, but phantoms. And so the Greek had a wholly different experience from the man who belonged to the ancient Oriental culture. The Greek had the feeling: There are indeed Gods, but for man it is only possible to have pictures of these Gods, just as we have in our memory pictures of past experiences, no longer the experiences themselves.

That was the fundamental feeling that took rise in the Greek Mysteries. The Greek felt that he had, as it were, memories of the Cosmos, not the appearance of the Cosmos itself, but pictures; pictures of the Gods, and not the Gods themselves. Pictures, too, of the events and processes on Saturn, Sun and Moon; no longer a living connection with what actually took place on Saturn, Sun and Moon,—the kind of living connection the human being has with his own childhood. The men of the Oriental civilisation had this real connection with Sun, Moon and Saturn, they had it from their Mysteries. But the Mysteries of the Greeks had a pictorial or image-character. There appeared in them the shadow-spirits of Divine-Spiritual Reality. And something else went with this as well that was very significant. For there was yet another difference between the Oriental Mysteries and the Greek.

In the Oriental Mysteries, if one wanted to know something of the sublime and tremendous experience that was possible in these Mysteries, one had always to wait until the right time. Some experience or other could perhaps only be found by making the appropriate sacrifice, the appropriate super-sensible ‘experiments’ as it were, in Autumn,—another only in Spring, another again at Midsummer, and another in the depth of Winter. Or again it might be that sacrifices were made to certain Gods at a time determined by a particular constellation of the Moon. At that special time the Gods would appear in the Mysteries, and men would come thither to be present at their manifestations. When the time had gone by one would have to wait, perhaps thirty years, until the opportunity should come again when those Divinities should once more reveal themselves in the Mysteries. All that related to Saturn, for example, could only enter the region of the Mysteries every thirty years; all that was concerned with the Moon about every eighteen years. And so on. The priests of the Oriental Mysteries were dependent on time, and also on place and on all manner of circumstances for receiving the sublime and tremendous knowledge and vision that came to them. Quite different manifestations were received deep in a mountain cave and high on the mountain top. Or again, the revelations were different, according as one was far inland in Asia or on the coast. Thus a certain dependence on place and time was characteristic of the Mysteries of the East.

In Greece the great and awful Realities had disappeared. Pictures there still were. And the pictures were dependent not on the time of year, on the course of the century, or on place; but men could have the pictures when they had performed this or that exercise, or had made this or that personal sacrifice. If a man had reached a certain stage of sacrifice and of personal ripeness, then for the very reason that he as a human being had attained thus far, he was able to have view of the shadows of the great world-events and of the great world-Beings.

That is the important change in the nature of the Mysteries that meets us when we pass from the ancient East to Greece. The ancient Oriental Mysteries were subject to the conditions of space and locality, whilst in the Greek Mysteries the human being himself came into consideration and what he brought to the Gods. The God, so to speak, came in his phantom or shadow-picture, when the human being, through the preparations he had undergone, had been made worthy to receive the God in phantom form. In this way the Mysteries of Greece prepared the road for modern humanity.

Now, the Mystery of Ephesus stood midway between the ancient Oriental Mysteries and the Greek Mysteries. It held a unique position. For in Ephesus those who attained to initiation were able still to experience something of the tremendous majestic truths of the ancient East. Their souls were still stirred with a deep inward experience of the connection of the human being with the Macrocosm and with the Divine-Spiritual Beings of the Macrocosm. In Ephesus men could still have sight of the super-earthly, and in no small measure. Self-identification with Artemis, with the Goddess of the Mystery of Ephesus, still brought to man a vivid sense of his relation to the kingdoms of nature. The plant world, so it taught him, is yours; the Earth has only received it from you. The animal world you have overcome. You have had to leave it behind. You must look back on the animals with the greatest possible compassion, they have had to remain behind on the road, in order that you might become Man. To feel oneself one with the Macrocosm: this was an experience that was still granted to the Initiate of Ephesus, he could still receive it straight from the Realities themselves.

At the same time, the Mysteries of Ephesus were, so to speak, the first to be turned westward. As such, they had already that independence of the seasons, or of the course of years and centuries; that independence too of place on Earth. In Ephesus the important things were the exercises that the human being went through, making himself ripe, by sacrifice and devotion, to approach the Gods. So that on the one hand, in the content of its Mystery truths, the Mystery of Ephesus harked back to the Ancient East, whilst on the other hand it was already directed to the development of man himself, and was thus adapted to the nature and character of the Greek. It was the very last of the Eastern Mysteries of the Greeks, where the great and ancient truths could still be brought near to men; for in the East generally the Mysteries had already become decadent.

It was in the Mysteries of the West that the ancient truths remained longest. The Mysteries of Hibernia still existed, centuries after the birth of Christianity. These Mysteries of Hibernia are nevertheless doubly secret and occult, for you must know that even in the so-called Akashic Records, it is by no means easy to search into the hidden mysteries of the statues of which I told you yesterday—the Sun Statue and the Moon Statue, the male and the female. To approach the pictures of the Oriental Mysteries and to call them forth out of the astral light is, comparatively speaking, easy for one who is trained in these things. But let anyone approach, or want to approach, the Mysteries of Hibernia in the astral light, and he will at first be dazed and stupefied. He will be beaten back. These Irish, these Hibernian Mysteries will not willingly let themselves be seen in the Akashic pictures, albeit they continued longest in their original purity.

Now you must remember, my dear friends, that the individuality who was in Alexander the Great had come into close contact with the Hibernian Mysteries during the Gilgamesh time, when he made his journey westward to the neighbourhood of the modern Burgenland. These Mysteries had lived in him, lived in him after a very ancient manner, for it was in the time when the West resounded still with powerful echoes of the Atlantean age. And now all this experience was carried over into the condition of human existence that runs its course between death and a new birth. Then later the two friends, Eabani and Gilgamesh, found themselves together again in life in Ephesus, and there they entered into a deeply conscious experience of what they had experienced formerly during the Gilgamesh time more or less unconsciously or sub-consciously, in connection with the Divine-Spiritual worlds.

Their life during this Ephesus time was comparatively peaceful, they were able to digest and ponder what they had received into their souls in more stormy days.

Let me remind you of what it was that passed over into Greece before these two appeared again in the decadence of the Greek epoch and the rise of the Macedonian. The Greece of olden time, the Greece that had spread abroad and embraced Ephesus also within its bounds, and had even penetrated right into Asia Minor, had still in her shadow-pictures the after-echo of the ancient time of the Gods. The connection of man with the spiritual world was still experienced, though in shadows. Greece was however gradually working herself free from the shadows; we may observe how step by step the Greek civilisation was wresting its way out of what we may call divine civilisation and taking on more and more the character of a purely earthly one.

My dear friends, it is only too true that the very most important things in the history of human evolution are simply passed over in the materialistic external history of to-day. Of extraordinary importance for the understanding of the whole Greek character and culture is this fact: that in the Greek civilisation we find no more than a shadow-picture, a phantom of the old Divine Presence wherein man had contact with the super-sensible worlds, for man was already gradually emerging out of this Divinity and learning to make use of his own individual and personal spiritual faculties. Step by step we can see this taking place. In the dramas of Æschylus we may see placed before us in an artistic picture the feeling that yet remained to man of the old time of the Gods. Scarcely however has Sophocles come forward when man begins to tear himself away from this conscious sense of union with Divine-Spiritual existence. And then something else appears that is coupled with a name which from one point of view we cannot over-estimate—but of course there are many points of view to be considered.

In the older Grecian time there was no need to make written history. Why was this? Because men had the living shadow of everything of importance that had happened in the past. History could be read in what came to view in the Mysteries. There one had the shadow-pictures, the living shadow-pictures. What was there then to write down as history?

But now came the time when the shadow pictures became submerged in the lower world, when human consciousness could no longer perceive them. Then came the impulse to make records. Herodotus,1Herodotus of Halicarnassos, the first Greek historian, lived in the fifth century B.C. Wrote history of the Persian Wars. the first prose historian, appeared. And from this time onward, many could be named who followed him, the same impulse working in them all,—to tear mankind away from the Divine-Spiritual and to set him down in the purely earthly. Nevertheless, as long as Greek culture and civilisation lasted, there is a splendour and a light shed abroad over this earth-directed tendency, a light of which we shall hear tomorrow that it did not pass over to Rome nor to the Middle Ages. In Greece, a light was there. Of the shadow-pictures, even the fading shadow-pictures of the evening twilight of Greek civilisation, man still felt that they were divine in their origin.

In the midst of all this, like a haven of refuge where men found clear enlightenment concerning what was present, as it were in fragments, in Greek culture,—in the midst stood Ephesus. Heraclitus received instruction from Ephesus, as did many another great philosopher; Plato, too, and Pythagoras. Ephesus was the place where the old Oriental wisdom was preserved up to a certain point. And the two souls who dwelt later in Aristotle and Alexander the Great were in Ephesus a little after the time of Heraclitus and were able to receive there of the heritage from the old knowledge of the Oriental Mysteries that the Mystery of Ephesus still retained. Notably the soul of Alexander entered into an intimate union with the very Being of the Mysteries as far as it was living in the Mystery of Ephesus.

And now we come to one of those historical events of which people may think that they are mere chance, but which have their foundations deep down in the inner connections of the evolution of humanity. In order to gain an insight into the significance of this event, let us call to mind the following. We must remember that in the two souls who afterwards became Aristotle and Alexander the Great, there was living in the first place all that they had received in a far-off time in the past and had subsequently elaborated and pondered. And then there was also living in their souls the treasure of untold value that had come to them in Ephesus. We might say that the whole of Asia—in the form that it had assumed in Greece, and in Ephesus in particular—was living in these two, and more especially in the soul of Alexander the Great, that is to say, of him who afterwards became Alexander the Great.

Picture to yourselves the part played by this personality. I described him for you as he was in the Gilgamesh time; and now you must imagine how the knowledge that belonged to the ancient East and to Ephesus, a knowledge which we may also call a “beholding,” a “perceiving,”—this knowledge was called up again in the intercourse between Alexander the Great and Aristotle, in a new form. Picture this to yourselves; and then think what would have happened if Alexander, in his incarnation as Alexander, had come again into contact with the Mystery of Ephesus, bearing with him in his soul the gigantic document of the Mystery of Ephesus, for this majestic document of knowledge lived with extraordinary intensity in the souls of these two. If we can form a idea of this, we can rightly estimate the fact that on the day on which Alexander was born, Herostratus threw the flaming torch into the Sanctuary of Ephesus; on the very day on which Alexander was born, the Temple of Diana of Ephesus was treacherously burnt to the ground. It was gone, never to return. Its monumental document, with all that belonged to it, was no longer there. It existed only as a historical mission in the soul of Alexander and in his teacher Aristotle.

And now you must bring all this that was alive in the soul of Alexander into connection with what I said yesterday, when I showed you how the mission of Alexander the Great was inspired by an impulse coming from the configuration of the Earth. You will readily understand how that which in the East had been real revelation of the Divine-Spiritual was as it were extinguished with Ephesus. The other Mysteries were at bottom only Mysteries of decadence, where traditions were preserved, though it is true these traditions did still awaken clairvoyant powers in specially gifted natures. The splendour and the glory, the tremendous majesty of the olden time were gone. With Ephesus was finally put out the light that had come over from the East.

You will now be in a position to appreciate the resolve that Alexander made in his soul: to restore to the East what she had lost; to restore it at least in the form in which it was preserved in Greece, in the phantom or shadow-picture. Hence his idea of making an expedition into Asia, going as far as it was possible to go, in order to bring to the East once more—albeit in the shadow form in which it still existed in the Grecian culture—what she had lost.

And now we see what Alexander the Great is really doing, and doing in a most wonderful way, when he makes this expedition. He is not bent on the conquest of existing cultures, he is not trying to bring Hellenism to the East in any external sense. Wherever he goes, Alexander the Great not only adopts the customs of the land, but is able too to enter right into the minds and hearts of the human beings who are living there, and to think their thoughts. When he comes to Egypt, to Memphis, he is hailed as a saviour and deliverer from the spiritual fetters that have hitherto bound the people. He permeates the kingdom of Persia with a culture and civilisation which the Persians themselves could never have produced. He penetrates as far as India.

He conceives the plan of effecting a balance, a harmony between Hellenic and Oriental civilisations. On every hand he founds academies. The academies founded in Alexandria, in Northern Egypt, are the best known and have had the greatest significance for later times. Of the first importance however is the fact that all over Asia larger and smaller academies were founded, in which the works of Aristotle were preserved and studied for a long time to come. What Alexander began in this way continued to work for centuries in Asia Minor, repeating itself again and again as it were in feebler echoes. With one mighty stroke Alexander planted the Aristotelian Knowledge of Nature in Asia, even as far as India. His early death prevented his reaching Arabia, though that had been one of his chief aims. He went however as far east as India, and also into Egypt. Everywhere he implanted the spiritual Knowledge of Nature that he had received from Aristotle, establishing it in such a way that it could become fruitful for men. For everywhere he let the people feel it was something that was their own,—not a foreign element, a piece of Hellenism, that was being imposed upon them. Only a nature such as Alexander's, able to fire others with his own enthusiasm, could ever have accomplished what he did. For everywhere others came forward to carry on the work he had begun. In the years that followed, many more scholars went over from Greece. Apart from Edessa it was one academy in particular, that of Gondishapur, which received constant reinforcements from Greece for many centuries to come.

A marvellous feat was thus performed! The light that had come over from the East,—extinguished in Ephesus by the flaming torch of Herostratus,—this light, or rather its phantom shadow, now shone back again from Greece, and continued so to shine until the dramatic moment when beneath the tyranny of Rome2Justinian, Byzantine Emperor from 527–565, son of a peasant, sent an edict to Athens in 529 forbidding the teaching of philosophy and law. Thereupon the last seven Athenian philosophers left the Roman Empire and emigrated to Persia. the Schools of the Greek philosophers were ultimately closed. In the 6th century A.D. the last of the Greek philosophers fled away to the academy of Gondishapur.

In all this we see two elements interworking; one that had gone, so to speak, in advance, and one that had remained behind. The mission of Alexander was founded, more or less unconsciously, upon this fact: the waves of civilisation had advanced in Greece in a Luciferian manner, whilst in Asia they had remained behind in an Ahrimanic manner. In Ephesus was the balance. And Alexander, on the day of whose birth the physical Ephesus had fallen, resolved to found a spiritual Ephesus that should send its Sun-rays far out to East and West. It was in very truth this purpose that lay at the root of all he undertook: to found a spiritual Ephesus, reaching out across Asia Minor eastward to India, covering also Egyptian Africa and the East of Europe.

It is not really possible to understand the spiritual evolution of Western humanity unless we can see it on this background. For soon after the attempt had been made to spread abroad in the world the ancient and venerated Ephesus, so that what had once been present in Ephesus might now be preserved in Alexandria,—be it only in a faltering hand instead of in large shining letters—soon after this second blooming of the flower of Ephesus, an altogether new power began to assert itself, the power of Rome. Rome, and all the word implies, is a new world, a world that has nothing to do with the shadow-pictures of Greece, and suffers man to keep no more than memories of these olden times. We can study no graver or more important incision in history than this. After the burning of Ephesus, through the instrumentality of Alexander the plan is laid for the founding of a spiritual Ephesus; and this spiritual Ephesus is then pushed back by the new power that is asserting itself in the West, first as Rome, later under the name of Christianity, and so on. And we only understand the evolution of mankind aright when we say: We, with our way of comprehending things through the intellect, with our way of accomplishing things by means of our will, we with our feelings and moods can look back as far as ancient Rome. Thus far we can look back with full understanding. But we cannot look back to Greece, neither can we look back to the East. There we must look in Imaginations. Spiritual vision is needed there. Yes, we can look South, as we go back along the stream of evolution; we can look South with the ordinary prosaic understanding, but not East. When we look East, we have to look in Imaginations. We have to see standing in the background the mighty Mystery Temples of primeval post-Atlantean Asia, where the Wise Men, the Priests, made plain to each one of their pupils his connection with the Divine-Spiritual of the Cosmos, and where was to be found a civilisation that could be received from the Mysteries in the Gilgamesh time, as I have described to you. We have to see these wonderful Temples scattered over Asia; and in the foreground Ephesus, preserving still within its Mystery much that had faded away in the other Temples of the East, whilst at the same time it had already itself made the transition and become Greek in character. For in Ephesus, man no longer needed to wait for the constellations of the stars or for the right time of year, nor to wait until he himself had attained a certain age, before he could receive the revelations of the Gods. In Ephesus, if he were ripe for it, he might offer up sacrifices and perform certain exercises that enabled him so to approach the Gods that they drew graciously near to him.

It was in this world that stands before you in this picture that the two personalities of whom we have spoken were trained and prepared, in the time of Heraclitus. And now, in 356 A.D. on the birth-day of Alexander the Great, we behold the flames of fire burst forth from the Temple of Ephesus.

Alexander the Great is born, and finds his teacher Aristotle. And it is as though from out of the ascending flames of Ephesus a mighty voice went forth for those who were able to hear it: Found a spiritual Ephesus far and wide over the Earth, and let the old physical Ephesus stand in men's memory as its centre, as its midmost point.

Thus we have before us this picture of ancient Asia with her Mystery centres, and in the foreground Ephesus and her pupils in the Mysteries. We see Ephesus in flames, and a little later we see the expeditions of Alexander that carried over into the East what Greece had to give for the progress of mankind, so that there came into Asia in picture-form what she had lost in its reality.

Looking across to the East and letting our imagination be fired by the tremendous events that we see taking place, we are able to view in a true light that ancient chapter in man's history,—for it needs to be grasped with the imagination. And then we see gradually rise up in the foreground the Roman world, the world of the Middle Ages, the world that continues down to our own time.

All other divisions of history into periods—ancient, medieval and modern, or however else they may be designated—give rise to false conceptions. But if you will study deeply and intently the picture that I have here set before you, it will give you a true insight into the hidden workings that run through European history down to the present day.

Fünfter Vortrag

Unter den alten Mysterien nimmt dasjenige von Ephesus eine ganz besondere Stellung ein. Ich habe ja mit jenem Entwickelungselemente in der Geschichte des Abendlandes, das sich anknüpft an den Namen des Alexander, auch dieses Mysteriums von Ephesus gedenken müssen. Man begreift den Sinn der neueren und älteren Geschichte nur, wenn man eingeht auf den Umschwung, den das Mysterienwesen, von welchem ja alle älteren Zivilisationen ausgegangen sind, erfahren hat vom Orient herüber nach dem Okzident, nach Griechenland also zunächst. Und dieser Umschwung besteht in dem Folgenden.

Sehen Sie, wenn man in alle älteren Mysterien des Morgenlandes hineinschaut, überall bekommt man den Eindruck: Da sind die Mysterienpriester in der Lage, große, bedeutsame Wahrheiten aus ihren Schauungen an ihre Schüler zu offenbaren. Ja, in je ältere Zeiten man zurückgeht, desto mehr sind diese Priesterweisen imstande, in den Mysterien die unmittelbare Gegenwart der Götter selber, der geistigen Wesenheiten, welche die planetarischen Welten, welche die Erdenerscheinungen lenken, hervorzurufen, so daß die Götter wirklich da waren.

Der Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Makrokosmos, er enthüllte sich ja in verschiedenen Mysterien auf eine ähnlich großartige Weise, wie ich sie Ihnen gestern für die Mysterien von Hybernia dargestellt habe und auch für dasjenige, was noch Aristoteles Alexander dem Großen zu sagen hatte. Vor allen Dingen lag aber das vor in allen altorientalischen Mysterien, daß das Moralische, die moralischen Impulse nicht streng geschieden waren von den natürlichen Impulsen. Indem Aristoteles den Alexander nach Nordwesten wies, wo die Geister des Wasserelementes die herrschenden waren, kam von dort nicht bloß ein physischer Impuls, wie heute vom Nordwesten der Wind oder andere rein physische Dinge kommen, sondern es kamen auch moralische Impulse mit den physischen Impulsen. Das Physische und das Moralische war eines. Das konnte es sein, weil überhaupt durch jene Erkenntnisse, welche in diesen Mysterien gegeben wurden, der Mensch sich mit der ganzen Natur er nahm ja den Geist der Natur wahr - als eine Einheit fühlte. Da ist zum Beispiel eines in dem Verhältnis des Menschen zur Natur, das etwa gerade in der Zeit liegt, die verflossen ist zwischen der Lebenszeit des Gilgamesch und der Lebenszeit jener Individualität, zu der er in seiner nächsten Inkarnation wurde in der Nähe des Mysteriums von Ephesus. Gerade in der Zeit finden wir noch ganz lebendig eine Anschauung über den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Geistnatur. Dieser Zusammenhang ist der folgende. Durch alles das, was da der Mensch kennenlernte über die Wirkung der Elementargeister in der Natur, über die Wirkung der intelligenten Wesenheiten in den planetarischen Vorgängen, kam der Mensch zu der Überzeugung: Da draußen sche ich überall ausgebreitet die Pflanzenwelt, die grünende, die sprießende, die sprossende, die fruchtende Pflanzenwelt. Da sehe ich die einjährigen Pflanzen auf der Wiese, auf dem Felde, die im Frühling heranwachsen, die im Herbste wieder vergehen; da sehe ich jahrhundertelang wachsende Bäume, welche Rinde und Holz außen bekommen und mit ihren Wurzeln weit in die Erde hineinreichen. Das alles, was da draußen wurzelt in den einjährigen Kräutern und Blumen, was da wächst mit festen Impulsen hinein in die Erde, das habe ich als Mensch einmal in mir getragen.

Sehen Sie, heute fühlt der Mensch, wenn irgendwo in einem Raume Kohlensäure ist, die durch die Atmung der Menschen entstanden ist: Diese Kohlensäure habe ich mit ausgeatmet. — Das fühlt der Mensch, daß er in den Raum die Kohlensäure hineingeatmet hat. Der Mensch ist ja heute, ich möchte sagen, nur noch in einem geringen Zusammenhange mit dem Kosmos. In dem luftigen Teile seines Wesens, in der Luft, die der Atmung und den sonstigen Luftprozessen, die im Organismus vor sich gehen, zugrunde liegt, da ist der Mensch ganz im lebendigen Zusammenhange mit der großen Welt, mit dem Makrokosmos. Er kann hinschauen auf die ausgeatmete Atemluft, auf die Kohlensäure, die in ihm war und die jetzt draußen ist. Aber so, wie der Mensch heute - er tut es ja nicht, aber er könnte es - hinschaut auf die ausgeatmete Kohlensäure, so schaute der Mensch, der in den orientalischen Mysterien entweder eingeweiht war oder aufgenommen hatte die Weisheit, die aus den orientalischen Mysterien nach außen geströmt ist, die ganze Pflanzenwelt an. Er sagte sich: Ich schaue zurück in der Weltenentwickelung auf eine alte Sonnenzeit. Da habe ich die Pflanzen noch in mir getragen. Und dann habe ich sie herausströmen lassen in die weiten Kreise des Erdenseins. Aber als ich die Pflanzen noch in mir trug, als ich noch jener Adam Kadmon war, der die ganze Erde umfaßte und die Pflanzenwelt mit, da war diese ganze Pflanzenwelt noch etwas Wässerig-Luftiges.

Der Mensch sonderte von sich ab diese Pflanzenwelt. Wenn Sie sich vorstellen, Sie würden die Größe erlangen der ganzen Erde und dann nach innen absondern Pflanzliches, das nun im wäßrigen Elemente sich metamorphosierend entsteht, vergeht, heranwächst, anders wird, verschiedene Gestalten eben annimmt, dann würden Sie in Ihr Gemüt heraufrufen, wie es einmal war. Und daß es einmal so war, das sagten sich diejenigen, die etwa in der Gilgamesch-Zeit im Oriente drüben ihre Bildung aufgenommen hatten. Und schauten sie dann auf das Pflanzenwachstum auf den Wiesen hin, dann sagten sie sich: Wir haben die Pflanzen abgesondert in einem früheren Stadium unserer Entwickelung, aber die Erde hat die Pflanzen aufgenommen. Das Wurzelhafte ist ihnen erst von der Erde verliechen worden, ebenso alles dasjenige, was das Holzige ist, was die Baumesnatur des Pflanzenhaften ist. - Aber das allgemein Pflanzenhafte, das hat der Mensch von sich abgesondert, und das ist von der Erde aufgenommen worden. Eine innige Verwandtschaft fühlte der Mensch mit allem Pflanzlichen.

Nicht eine gleiche Verwandtschaft fühlte der Mensch mit dem höheren Tierischen, denn er wußte, er konnte sich nur dadurch auf die Erde heraufarbeiten, daß er überwunden hat die tierische Bildung, daß er zurückgelassen hat auf seinem Entwickelungswege die Tiere. Die Pflanzen hat er bis zur Erde mitgenommen, sie dann der Erde übergeben, so daß die Erde sie in ihren Schoß aufnahm. Er wurde für die Pflanzen auf der Erde der Vermittler der Götter, der Vermittler zwischen den Göttern und der Erde.

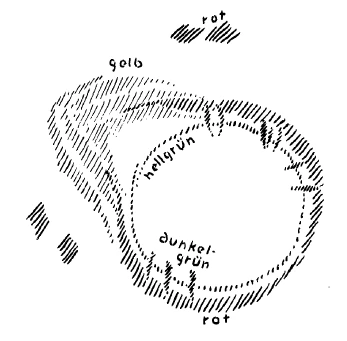

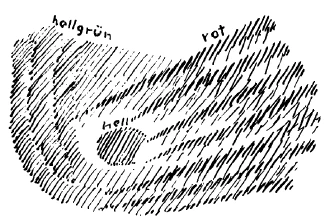

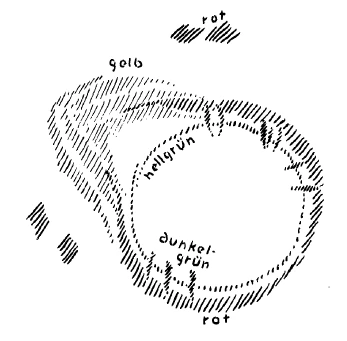

Daher fühlten solche Menschen, die nun wirklich jenes große Erlebnis hatten, das man skizzenhaft ganz einfach darstellen kann (siehe Zeichnung): Der Mensch kommt an die Erde heran aus dem Weltenall (gelb). Die Zahl kommt ja nicht in Betracht, da, wie ich schon gestern sagte, die Menschen ineinanderstaken. Er sondert alles Pflanzliche ab, und die Erde nimmt das Pflanzliche auf und gibt ihm das Wurzelhafte (dunkelgrüne Striche). - So fühlte der Mensch, wie wenn er mit dem Pflanzenwachstum gewissermaßen die Erde umschlungen hätte (rote Umhüllung) und wie wenn die Erde dankbar gewesen wäre für dieses Umschlungenwerden und aufgenommen hat dasjenige, was ihr der Mensch an wäßtig-luftigen Pflanzenelementen zuhauchen konnte. Und diejenigen, die solches fühlten, die fühlten sich in bezug auf dieses Pflanzenbringen zur Erde als innig verwandt mit dem Gotte, mit dem Hauptgotte des Merkur. Durch diese Empfindung, man habe selber die Pflanzen auf die Erde gebracht, kam man in eine besondere Beziehung zu dem Gotte Merkur.

Dagegen fühlte man gegenüber den Tieren: man konnte sie nicht mit auf die Erde bringen, man mußte sie absondern, man mußte sich freimachen von ihnen, sonst hätte man die menschliche Gestalt nicht in der richtigen Weise entwickeln können. Man schob gewissermaßen die Tiere von sich ab, so daß die Tiere eben weggeschoben wurden vom Menschen (rote Striche nach außen) und dann für sich eine Entwickelung durchmachen mußten auf einer niedrigeren Stufe, als der Mensch selber steht. So fühlte sich auf der einen Seite der alte Mensch gerade der Gilgamesch-Zeit und der folgenden Zeit hineingestellt zwischen das Tierreich und das Pflanzenreich. Dem Pflanzenreich gegenüber fühlte er sich als der Träger, der die Erde sozusagen besamt in Vertretung der Götter. Dem Tierreich gegenüber fühlte er sich so, als ob er es von sich abgestoßen hätte, um Mensch zu werden ohne die Belastung mit den Tieren, die dadurch verkümmert sind. Der ganze ägyptische Tierdienst hängt übrigens mit dieser Anschauung zusammen. Vieles in Asien drüben von jenem tiefen Mitleid, das man da findet gegenüber den Tieren, hängt damit zusammen. Und es war eben eine großartige Naturanschauung, die so fühlte die Verwandtschaft des Menschen mit der Pflanzenwelt auf der einen Seite, mit der tierischen Welt auf der anderen Seite. Der Tierwelt gegenüber fühlte man die Befreiung, der pflanzlichen Welt gegenüber fühlte man die innige Verwandtschaft mit ihr. Man fühlte als Mensch die Pflanzenwelt als ein Stück von sich selber, und man fühlte die Erde in inniger Liebe, weil die Erde dieses Stück Menschentum, das die Pflanzen sind, in sich aufgenommen hat, in sich einwurzeln ließ, ja sogar aus ihrem Material sie mit Rinde überzog in den Bäumen. Überall war Moralisches in der Beurteilung der physischen Umwelt vorhanden. Man ging an die Pflanzen der Wiese heran und empfand in diesen nicht nur das natürliche Wachstum, sondern eine moralische Beziehung des Menschen zu diesem Wachstum. Man empfand den Tieren gegenüber wieder eine moralische Beziehung: man hat sich über sie hinausgerungen.

Dagegen fühlte man gegenüber den Tieren: man konnte sie nicht mit auf die Erde bringen, man mußte sie absondern, man mußte sich freimachen von ihnen, sonst hätte man die menschliche Gestalt nicht in der richtigen Weise entwickeln können. Man schob gewissermaßen die Tiere von sich ab, so daß die Tiere eben weggeschoben wurden vom Menschen (rote Striche nach außen) und dann für sich eine Entwickelung durchmachen mußten auf einer niedrigeren Stufe, als der Mensch selber steht. So fühlte sich auf der einen Seite der alte Mensch gerade der Gilgamesch-Zeit und der folgenden Zeit hineingestellt zwischen das Tierreich und das Pflanzenreich. Dem Pflanzenreich gegenüber fühlte er sich als der Träger, der die Erde sozusagen besamt in Vertretung der Götter. Dem Tierreich gegenüber fühlte er sich so, als ob er es von sich abgestoßen hätte, um Mensch zu werden ohne die Belastung mit den Tieren, die dadurch verkümmert sind. Der ganze ägyptische Tierdienst hängt übrigens mit dieser Anschauung zusammen. Vieles in Asien drüben von jenem tiefen Mitleid, das man da findet gegenüber den Tieren, hängt damit zusammen. Und es war eben eine großartige Naturanschauung, die so fühlte die Verwandtschaft des Menschen mit der Pflanzenwelt auf der einen Seite, mit der tierischen Welt auf der anderen Seite. Der Tierwelt gegenüber fühlte man die Befreiung, der pflanzlichen Welt gegenüber fühlte man die innige Verwandtschaft mit ihr. Man fühlte als Mensch die Pflanzenwelt als ein Stück von sich selber, und man fühlte die Erde in inniger Liebe, weil die Erde dieses Stück Menschentum, das die Pflanzen sind, in sich aufgenommen hat, in sich einwurzeln ließ, ja sogar aus ihrem Material sie mit Rinde überzog in den Bäumen. Überall war Moralisches in der Beurteilung der physischen Umwelt vorhanden. Man ging an die Pflanzen der Wiese heran und empfand in diesen nicht nur das natürliche Wachstum, sondern eine moralische Beziehung des Menschen zu diesem Wachstum. Man empfand den Tieren gegenüber wieder eine moralische Beziehung: man hat sich über sie hinausgerungen.

Also eine großartige Geistnatur-Anschauung strömte aus von diesen Mysterien drüben im Oriente. Mysterien waren dann auch, aber mit einer weit weniger realen Geistnatur- Anschauung, in Griechenland. Die griechischen Mysterien sind grandios, gewiß, aber sie unterscheiden sich ganz wesentlich von den orientalischen Mystetien. Es ist eben alles so in den orientalischen Mysterien, daß der Mensch sich eigentlich nicht auf der Erde fühlt durch sie, sondern sich angegliedert fühlt an den Kosmos, an das Weltenall. In Griechenland war auch das Mysterienwesen zuerst auf der Stufe angekommen, wo der Mensch sich mit der Erde in Verbindung fühlte. Daher war dasjenige, was im Oriente entweder erschien oder empfunden wurde in den Mysterien, die wesenhaft geistige Welt selber. Man schildert eben die absolute Wahrheit, wenn man sagt: In den altorientalischen Mysterien erschienen die Götter selber unter den Priestern, die da opferten und die Gebete verrichteten. — Die Mysterientempel waren zu gleicher Zeit die irdischen Gaststätten der Götter, wo die Götter eben das den Menschen schenkten dutch die Priesterweisen, was sie ihnen an Himmelsgütern zu schenken hatten. In den griechischen Mysterien erschienen nur mehr die Bilder der Götter, die Abbilder, etwas wie die Schattenbilder; wahrhafte, echte Bilder, aber wie Schattenbilder, nicht mehr die göttlichen Wesenheiten, nicht mehr die Realitäten, sondern die Schattenbilder. So daß der Grieche eine ganz andere Empfindung hatte als derjenige, welcher der alten orientalischen Kultur angehörte. Der Grieche hatte die Empfindung: Es gibt Götter, aber den Menschen ist nur möglich, Bilder von diesen Göttern zu haben, so wie man in der Erinnerung die Bilder der Erlebnisse hat, nicht mehr die Erlebnisse selber.

Das war die tiefe Grundempfindung, die aus den griechischen Mysterien herauskam, daß die Menschen die Empfindung hatten, sie haben etwas wie Erinnerungen an den Kosmos, nicht die Erscheinung des Kosmos selber, Bilder vom Kosmos, Bilder der Götter, nicht die Götter selber, Bilder von den Vorgängen auf Saturn, Sonne, Mond, nicht mehr die lebendige Verbindung mit dem, was real war auf Saturn, Sonne, Mond, wie der Mensch etwa die reale Verbindung mit seiner Kindheit hat. Und diese reale Verbindung mit Sonne, Mond, Saturn hatten eben die Menschen der orientalischen Zivilisation aus ihren Mysterien heraus. So hatte das Mysterienwesen der Griechen etwas Bildhaftes. Es erschienen eben die Schattengeister der göttlich-geistigen Wirklichkeit. Aber das hatte etwas bedeutsames anderes gebracht. Denn sehen Sie, es gab noch einen Unterschied zwischen den orientalischen Mysterien und den griechischen.

Bei den orientalischen Mysterien war es doch immer so, daß wenn man irgend etwas von dem Großartigen, Gigantischen, das man da erfahren konnte, wissen wollte, daß man erst die rechte Zeit abzuwarten hatte. Da war es so, daß man irgend etwas nur erfahren konnte, wenn man den Opferdienst, der dazugehörte, also gewissermaßen die übersinnlichen Experimente, im Herbste machte, andere im Frühling, andere zur Hochsommetzeit, andere im tiefen Winter. Und wiederum, es war möglich, daß zu irgendeiner Zeit, die man dadurch als die richtige erkannte, daß die Mondkonstellation eine bestimmte war, irgendwelchen Göttern geopfert wurde. Dann erschienen sie in den Mysterien. Man kam zu ihren Öffenbarungen. Dann mußte man wiederum, sagen wir, dreißig Jahre warten, bis wiederum dieselbe Gelegenheit war, daß irgendeine Götterwesenheit sich in den Mysterien zeigte. Zum Beispiel alles dasjenige, was sich auf Saturn bezog, konnte nur alle dreißig Jahre irgendwie in den Bereich der Mysterien treten, alles was sich auf den Mond bezog, ungefähr immer in achtzehn Jahren und so weiter. So daß die Priesterweisen der orientalischen Mysterien die grandiosen, gigantischen Erkenntnisse und Anschauungen, die sie gewannen, eben nur in Abhängigkeit von Zeit und Raum und allem möglichen bekamen. Man bekam zum Beispiel ganz andere Offenbarungen tief in Berghöhlen drinnen, andere Offenbarungen auf den Gipfeln der Berge. Man bekam andere Offenbarungen, wenn man irgendwie tiefer in Asien drüben war oder an der Küste war und dergleichen. Also eine gewisse Abhängigkeit von Raum und Zeit auf der Erde, das war das Charakteristische gerade der Mysterien des Orients.

In Griechenland waren die großen gigantischen Realitäten dahingeschwunden. Bilder waren noch da. Aber die Bilder konnte man jetzt haben nicht in Abhängigkeit von Jahreszeit oder Jahrhundertlauf oder dem Orte, sondern die Bilder konnte man haben, wenn man sich als Mensch in der richtigen Weise vorbereitete, wenn man diese oder jene Exerzitien machte, diese oder jene persönlichen Opfer brachte. Wenn man dann auf einer gewissen Stufe der Opfer und der persönlichen Reife angekommen war, dann konnte man deshalb, weil man das als Mensch erreicht hatte, die Wahrnehmungen der Schatten der großen Weltereignisse und Weltwesenheiten haben.

Das ist der große Umschwung im Mysterienwesen vom alten Orient nach Griechenland herüber, daß die alten orientalischen Mysterien unterworfen waren den Bedingungen von Erdenort und Erdenraum, daß die griechischen Mysterien diejenigen waren, wo der Mensch in Betracht kam mit dem, was er den Göttern entgegenbrachte. Der Gott kam sozusagen in seinem Schattenbilde, in seinem Spektrum, wenn der Mensch gewürdigt werden konnte durch die Vorbereitungen, die er dazu gemacht hatte, daß der Gott im Spektrum zu ihm kam. Dadurch sind die griechischen Mysterien wirklich die Vorbereitung der neueren Menschheit geworden.

Nun, mitten drinnen zwischen den alten orientalischen und den griechischen Mysterien stand das von Ephesus. Es hatte eben seine besondere Stellung. Denn in Ephesus konnten jene, die dort die Einweihung gewannen, durchaus noch etwas von den gigantischen, majestätischen Wahrheiten des alten Orients erfahren. Sie wurden noch berührt von dem inneren Empfinden und Fühlen des Zusammenhanges des Menschen mit dem Makrokosmos und dem göttlich-geistigen Wesen des Makrokosmos. Oh, in Ephesus war noch viel von dem wahrzunehmen, was überirdisch war. Und die Identifizierung mit der Artemis, mit der Göttin des Mysteriums von Ephesus, die brachte eben noch jenen lebendigen Zusammenhang: Die Pflanzenwelt ist die deine, die Erde hat sie nur aufgenommen. Die Tierwelt hast du überwunden, du hast sie zurücklassen müssen. Du mußt möglichst mit Mitleid schauen auf die Tiere, die auf dem Wege zurückbleiben mußten, damit du Mensch werden konntest. — Dieses Sich-eins-Fühlen mit dem Makrokosmos, das wurde noch aus den unmittelbaren Erlebnissen, noch aus den Realitäten dem Eingeweihten von Ephesus überliefert.

Aber es war in Ephesus schon als dem ersten Mysterium, das gegen das Abendland zugekehrt war, die Unabhängigkeit von den Jahreszeiten oder von dem Jahrhundertlauf, kurz, von Ort und Zeit auf Erden. In Ephesus kam es schon an auf die Exerzitien, die der Mensch machte, auf die Art und Weise, wie er sich durch Opferung und Hingabe an die Götter reif gemacht hatte. So daß in der Tat das Mysterium von Ephesus auf der einen Seite durch den Inhalt der Mysterienwahrheiten noch hinweist nach dem alten Oriente, und dadurch, daß es schon herangerückt war an die menschliche Entwickelung, an das Menschentum, war das Mysterium von Ephesus wiederum dem Griechentum schon zugeneigt. Es war sozusagen das letzte Mysterium da drüben im Osten, wo noch die alten gigantischen Wahrheiten an die Menschen herantraten, herantreten konnten. Denn im Osten waren sonst die Mysterien schon in die Dekadenz gekommen.

Wo die alten Wahrheiten sich am längsten erhalten haben, das ist in den Mysterien des Westens. Von Hybernia kann man noch erzählen Jahrhunderte nach der Entstehung des Christentums. Aber ich möchte sagen: Die Geheimnisse von Hybernia, sie sind im Grunde genommen doppelt geheimnisvoll. - Denn sehen Sie, das, was ich Ihnen gestern erzählt habe von diesen zwei Statuen, wovon die eine eine Sonnen-, die andere eine Mondesstatue ist, eine männliche und eine weibliche Statue ist, diese Geheimnisse von den Statuen sind heute so, daß sie selbst aus der sogenannten Akasha-Chronik noch schwer zu erforschen sind. Es ist verhältnismäßig gar nicht schwierig für denjenigen, der in diesen Dingen geschult ist, heranzukommen an die Bilder der orientalischen Mysterien und aus dem Astrallichte heraus diese Bilder zu holen. Aber kommt man oder will man an die Mysterien von Hybernia herankommen, will man sich ihnen nähern im Astrallichte, so bekommt man zunächst etwas wie eine Betäubung. Es schlägt einen zurück. Sie wollen selbst in den Akasha-Nachbildungen sich heute nicht mehr sehen lassen, trotzdem sie am längsten bestanden haben in ursprünglicher Echtheit, diese irischen, diese hybernischen Mysterien.

Nun bedenken Sie: Berührt von den hybernischen Mysterien war ja die Individualität, die in Alexander dem Großen steckte, während der Gilgamesch-Zeit, während des Zuges nach dem Westen bis in die Gegend des heutigen Burgenlandes. Es lebte in dieser Menschenindividualität und lebte auf eine sehr alte Art in der Zeit, in der eben durchaus noch starke Anklänge in diesem Westen waren an die atlantische Zeit. Das war nun durch den seelischen Zustand, der zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt verfließt, hindurchgetragen. Dann waren die beiden Freunde, Eabani und Gilgamesch, wiederum eben gerade in Ephesus, um dort mit einer großen Bewußtheit dasjenige zu erleben, was mehr oder weniger noch unbewußt, unterbewußt im Zusammenhange mit der göttlich-geistigen Welt vorher während der Gilgamesch-Zeit erlebt worden war. Aber es war während der ephesischen Zeit ein verhältnismäßig ruhiges Leben, ein Verdauen, Verarbeiten desjenigen, was in früheren, bewegteren Zeiten in die Seelen hineingezogen war.

Nun muß man bedenken: Bevor diese Individualitäten wiederum erschienen in der Dekadenz der Griechenzeit, in dem Aufblühen der makedonischen Zeit, was war da über Griechenland hinweggegangen! Dieses Griechenland der alten Zeit, das im Grunde genommen sich über das Meer hinüber ausdehnte und auch Ephesus umfaßte, bis tief nach Kleinasien hineinging, dieses Griechenland, das hatte eben in den Schattenbildern durchaus noch den Nachklang der alten Götterzeit. Im Schatten wurde der Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der geistigen Welt wohl erlebt. Aber aus dem Schatten arbeitete sich das Griechentum allmählich heraus, und wir sehen ja stufenweise, wie sich die griechische Zivilisation aus einer sozusagen göttlichen Zivilisation in eine rein irdische hineinarbeitet.

Oh, die wichtigsten Dinge des geschichtlichen Werdens werden ja gar nicht berührt in dem, was heute ganz materialistisch äußere Geschichte ist! Wichtig für die ganze Auffassung des Griechentums ist das allerdings, weil nur mehr ein Schattenbild da war in der griechischen Zivilisation von der alten Göttlichkeit, in der der Mensch zusammenhing mit den übersinnlichen Welten, daß der Mensch allmählich herauskam aus der Götterwelt und zu dem Gebrauche seiner eigenen, ganz individuell persönlichen geistigen Fähigkeiten kam. Das ging stufenweise vor sich. Wir können es den Dramen des Äschylos noch ansehen, wie da dasjenige, was noch gefühlt wird von der alten Götterzeit, wie das nun noch auftritt in künstlerischem Bilde. Aber kaum kommt Sophokles, so reißt schon sozusagen der Mensch sich ab von diesem Sich-zusammen-Fühlen mit dem göttlich-geistigen Dasein. Und dann, dann tritt etwas ein, was an einen Namen geknüpft ist, der ganz gewiß nicht hoch genug zu schätzen ist von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus; aber es gibt ja verschiedene Gesichtspunkte in der Welt.

Sehen Sie, in älteren griechischen Zeiten hatte man wahrhaftig nicht notwendig, Geschichte aufzuzeichnen. Wozu denn? Es war ja die lebendige Abschattung da des wichtigen Vergangenen. Die Geschichte las man ab in demjenigen, was sich in den Mysterien zeigte. Da waren die Schattenbilder, die lebendigen Schattenbilder. Was sollte man denn aufschreiben als Geschichte? Da kam die Zeit, wo diese Schattenbilder hinuntergingen in die untere Welt, wo das menschliche Bewußtsein sie nicht mehr aufnehmen konnte. Da entstand zuerst der Drang, nun Geschichte aufzuschreiben. Da kam der erste Prosaiker der Geschichte, Herodot, herauf. Und man könnte von da an viele Namen nennen, immer zielt das daraufhin, sozusagen herauszureißen die Menschheit aus dem Göttlich-Geistigen, sie hinzustellen in das rein Irdische. Aber immerhin war über diesem ganzen Irdischwerden während des Griechentums ein Glanz, ein Glanz, von dem wir morgen hören werden, daß er eben nicht auf das Römertum und nicht auf das Mittelalter übergegangen ist. Ein Glanz war da. Den Schattenbildern, auch den in der Abenddämmerung der griechischen Zivilisation verglimmenden Schattenbildern spürte man es noch an, empfand man es an, daß sie göttlichen Ursprungs waren.

Und inmitten von all dem, wie die Zufluchtsstätte, wo man Aufklärung fand über all das, was da in Griechenland, ich möchte sagen, in Fragmenten der Kultur vorhanden war, inmitten von all dem stand Ephesus. Heraklit, viele der größten Philosophen, auch Platon, Pythagoras, sie alle haben noch von Ephesus gelernt. Ephesus war wirklich dasjenige, was bis zu einem gewissen Punkte bewahrt hatte die alten orientalischen Weistümer. Und auch diejenigen Individualitäten, die in Aristoteles und Alexander dem Großen waren, in Ephesus konnten sie erfahren, etwas später als Heraklit, was dann noch an altem Wissen in den orientalischen Mysterien war, das als Erbstück geblieben ist dem Mysterium von Ephesus. Innig verbunden insbesondere mit der Alexanderseele war dasjenige, was in Ephesus an Mysterienwesen lebte. Und nun geschah eines jener historischen Ereignisse, von denen die Triviallinge annehmen, daß sie ein äußerer Zufall sind, die aber gerade tief, tief begründet sind in den inneren Zusammenhängen der Menschheitsentwickelung.

Um die Bedeutung dieses historischen Ereignisses einsehen zu können, rufen wir uns das Folgende einmal vor die Seele. Denken Sie daran, daß ja in den beiden Seelen, in der Seele desjenigen, der dann Aristoteles wurde, und desjenigen, der Alexander der Große wurde, zunächst das lebte, was innerlich verarbeitet war aus uralter Zeit heraus, dann das lebte, was in Ephesus ihnen ungeheuer wertvoll geworden war. Ich möchte sagen, ganz Asien, aber in der Form, in der es griechisch geworden war in Ephesus, lebte in den beiden, insbesondere in der Seele desjenigen, der später Alexander der Große geworden ist. Nun stelle man sich auch den Charakter vor — ich habe ihn geschildert aus der Gilgamesch-Zeit -, und man denke sich, daß sich ja nun im lebendigen Verkehr zwischen Alexander und Aristoteles das Wissen, das an den alten Orient und an Ephesus gebunden war, wiederholte, aber in der neuen Form des Wissens wiederholte. Man stelle sich das nur vor. Man stelle sich vor, was hätte werden müssen, wenn das gigantische Dokument, das eigentlich in diesen Seelen mit einer ungeheuren Intensität gelebt hat, wenn dieses gigantische Dokument, das Mysterium von Ephesus, dagewesen wäre, wenn also auch in der Alexander-Inkarnation Alexander das Mysterium von Ephesus noch angetroffen hätte! Man stelle sich das vor, und man würdige dann die Tatsache, daß an dem Tage, an dem Alexander geboten wurde, Herostrat die Brandfackel in das Heiligtum von Ephesus geworfen hat, so daß der Dianentempel von Ephesus an dem Tage, an dem Alexander geboren wurde, durch Frevlerhand abgebrannt ist. Es ward nicht mehr gefunden dasjenige, was gerade geknüpft war an seine Denkmal-Dokumente. Das war nun nicht da; das war im Grunde genommen allein jetzt als historische Mission in der Seele des Alexander und in seinem Lehrer Aristoteles.

Und nun verbinden Sie dasjenige, was da in ihnen als Seelisches lebte, mit dem, was ich gestern, als wie aus der Konfiguration der Erde heraus folgend, in der Mission Alexanders des Großen zeigte. Und nun werden Sie verstehen können, daß ja mit Ephesus wie ausgelöscht war dasjenige, was im Orient real, reale Offenbarung des Göttlich-Geistigen war. Die anderen Mysterien waren im Grunde genommen nur noch Dekadenzmysterien, in denen Traditionen aufbewahrt wurden, wenn auch manchmal sehr lebhafte Traditionen, und Traditionen, die in besonders veranlagten Naturen allerdings hellseherische Kräfte hervorriefen. Aber die Großartigkeit, das Gigantische der alten Zeit war nicht da. Mit Ephesus war ausgelöscht dasjenige, was aus Asien herübergekommen war. Nun würdigen Sie den Entschluß in der Seele Alexanders des Großen: Diesem Orient, der verloren hat dasjenige, was er einst hatte, muß es wenigstens gebracht werden in der Form, in der es in Griechenland im Schattenbilde sich bewahrt hat! - Damit entstand der Gedanke Alexanders des Großen, hinüberzuziehen nach Asien, so weit als nur gezogen werden konnte, um das, was der Orient verloren hatte, ihm im Schattenbilde in der griechischen Kultur wiederum zu bringen.

Und nun sehen wir, wie mit diesem Zug Alexanders des Großen tatsächlich in einer ganz wunderbaren Weise nicht eine Kultureroberung gemacht wird, wie man nicht versucht, irgendwie Hellenentum in einer äußeren Weise dem Orientalen zu bringen, sondern Alexander der Große nimmt überall nicht nur die Sitten des Landes an, sondern er ist überall imstande, aus den Herzen, aus den Gemütern der Menschen heraus zu denken. Als er nach Ägypten, nach Memphis kommt, wird er als ein Befreier von all dem geistigen Sklavenzeug angesehen, das bis dahin geherrscht hat. Das Perserreich durchdringt er mit einer Kultur, mit einer Zivilisation, zu der die Perser niemals imstande gewesen sind. Bis nach Indien dringt er vor. Den Plan faßt er, den Ausgleich, die Harmonisierung zu bewirken zwischen hellenischer und orientalischer Zivilisation. Überall gründet er Akademien. Die bedeutsamsten für die Nachwelt sind ja dann die Akademien, die er in Alexandria, in Nordägypten, gründete. Aber das allerwichtigste ist, daß er überall in Asien drüben große und kleine Akademien gründet, in denen dann in der folgenden Zeit die Werke des Aristoteles, auch die Traditionen des Aristoteles gepflegt werden. Und das hat durch Jahrhunderte in Vorderasien weitergewirkt, so weitergewirkt, daß, ich möchte sagen, immerfort noch wie im schwachen Nachbilde sich das wiederholt hat, was Alexander inaugurierte. Alexander hat zunächst in einem mächtigen Stoß das Naturwissen drüben in Asien gepflanzt bis nach Indien hinein durch seinen frühen Tod war er nur nicht imstande, bis nach Arabien zu kommen: Das war sein Hauptziel. Bis nach Indien hinein, bis nach Ägypten hinein, überallhin verpflanzte er das, was er als Naturgeist-Wissen von Aristoteles aufgenommen hatte. Und er hat es überall so hingestellt, daß es fruchtbar werden konnte dadurch, daß die Menschen, die es aufnehmen sollten, es als ihr Eigenes empfanden, nicht als ein fremdes Hellenisches, das ihnen aufgedrängt werden sollte. Es konnte tatsächlich nur eine so feuersprühende Natur wie Alexander der Große dies bewirken, was da bewirkt worden ist. Denn immerdar kamen Nachschübe. Viele Gelehrte der späteren Zeit gingen wiederum von Griechenland hinüber, und insbesondere war es eine der Akademien - außer Edessa war es die Akademie von Gondishapur -, welche durch Jahrhunderte hindurch immer wieder und wiederum Nachzüge aus Griechenland erfahren hat.

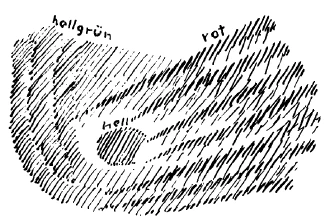

Da wurde das Ungeheure vollzogen, daß dasjenige, was vom Oriente herübergekommen war (es wurde gezeichnet, wobei sich die beiden Zeichnungen überschnitten; siehe Originaltafel 8. Rot von rechts nach links, heller Fleck), was in Ephesus gestoppt worden ist dutch die Brandfackel des Herostrat, daß das von seinem Schattenbilde, das in Griechenland war, zurück beleuchtet wurde (hellgrün von links nach rechts) bis zum letzten Akt, als durch oströmische Tyrannei die griechischen Philosophenschulen geschlossen wurden im 6. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderte und die letzten der griechischen Philosophen sich hinüberflüchteten nach der Akademie von Gondishapur.

Es war dieses ein Ineinanderarbeiten desjenigen, was vorangegangen war, und desjenigen, was zurückgeblieben war. Dadurch war in der Tat in dieser Mission, wenn auch mehr oder weniger unbewußt, aber es war darinnen, daß ja in einer gewissen Weise in Griechenland die Welle des Zivilisationslebens angekommen war auf eine luziferische Art, in Asien drüben sie zurückgeblieben war auf eine ahrimanische Art; in Ephesus war der Ausgleich. Und Alexander wollte, da Ephesus physisch an seinem Geburtstage zugrunde gegangen war, ein geistiges Ephesus, das seine Sonnenstrahlen über Orient und Okzident ausstrahlen sollte, begründen. In tieferem Sinne lag dem Wollen Alexanders zugrunde, ein geistiges Ephesus zu begründen über Vorderasien bis nach Indien hinein, über das ägyptische Afrika, über den Osten von Europa.

Man kann nicht die geschichtliche Entwickelung der abendländischen Menschheit verstehen, wenn man diesen Hintergrund nicht hat. Denn bald nachdem dies geschehen war, nachdem hier versucht worden war, das uralt ehrwürdige Ephesus auf breitem Raum auszubreiten, wurde im Grunde genommen in Alexandrien in Ägypten, wenn auch in matten Schriftzeichen, dasjenige bewahrt, was in leuchtenden weiten Lettern einmal vorhanden war in Ephesus. Und nachdem geblüht hat diese Nachblüte von Ephesus, machte sich ja geltend weiter im Westen drüben das Römertum, das nun eine ganz andere Welt ist, das nichts mehr zu tun hat mit den griechischen Schattenbildern, sondern das im menschlichen Wesen eben nur die Erinnerungen an diese alten Zeiten zurückbehält. Daher ist der wichtigste Einschnitt, der in der Geschichte studiert werden kann, der, als nach dem Brande von Ephesus begründet werden soll durch Alexander ein geistiges Ephesus, das dann zurückgeschoben wird von demjenigen, was sich weiter im Westen geltend macht, zuerst als Römertum, dann als Christentum und so weiter. Und man versteht die Entwickelung der Menschheit nur, wenn man sich sagt: So wie wir sind, mit unserer Art, mit dem Verstand aufzufassen, mit unserer Art, aus dem Willen heraus zu wirken, mit unserer Gemütsstimmung, so können wir zurückschauen in das alte Rom. Da versteht man alles. Aber man kann nicht zurückschauen nach Griechenland, nicht nach dem Oriente. Da muß man in Imaginationen schauen, dazu ist geistiges Schauen notwendig.

Ja, nach Süden dürfen wir schauen auch im geschichtlichen Werden mit dem gewöhnlichen, nüchtern prosaischen Verstande, nicht aber nach dem Osten. Denn wenn wir nach dem Osten schauen, müssen wir in Imaginationen schauen: hinten auf dem Hintergrunde die mächtigen Mysterientempel des uralten Asien der nachatlantischen Zeit, wo die Priesterweisen jedem ihrer Schüler seinen Zusammenhang mit dem Göttlich-Geistigen des Kosmos klarlegten, wo eine Zivilisation war, wie sie, wie ich Ihnen geschildert habe, in der Gilgamesch-Zeit aufgenommen werden konnte. Dann müssen wir sehen, indem wir über Asien zerstreut diese wunderbaren Tempel schauen, wie im Vordergrunde Ephesus steht, bewahrend noch vieles von dem, was schon abgeblaßt war in den über Asien zerstreuten Tempeln, vieles von dem noch bewahrend, aber schon ins Griechentum übergegangen. Schon braucht der Mensch nicht mehr auf die Sternkonstellationen und Jahreszeiten zu warten und auf seine eigenen Lebensalter, um die Offenbarungen der Götter zu empfangen in Ephesus, sondern schon kann er durch dasjenige, was er, wenn er reif ist, opfert, wenn er Exerzitien macht, sich den Göttern nahen, so daß sie gnadevoll zu ihm kommen. Und nun sehen wir in einer Welt, die durch dieses Bild wiedergegeben wird, in der Heraklit-Zeit, vorbereitet die Persönlichkeiten, von denen ich Ihnen gesprochen habe, nun sehen wir 356, am Geburtstage Alexanders des Großen, die Feuerflammen auflodern aus dem Tempel von Ephesus. Alexander der Große wird geboren, findet seinen Lehrer Aristoteles. Und es ist, wie wenn aus diesen zum Himmel aufsteigenden Feuerflammen von Ephesus heraus ertönen würde für diejenigen, die verstehen konnten: Begründet ein geistiges Ephesus, wo in den Weiten das alte physische Ephesus wie sein Mittelpunkt, wie sein Zentrum in der Erinnerung dastehen kann.

Und so sehen wir dieses Bild des alten Asien mit seinen Mysterienstätten, im Vordergrunde Ephesus, brennend, seine Schüler, und gleichzeitig fast, in etwas späterer Zeit, die Alexanderzüge, die das, was Griechenland im Fortschritte der Menschheit geben konnte, hinübertrugen, so daß im Bilde nach Asien kam, was Asien an Realität verloren hatte.

Und indem wir da hinüberschauen, unsere Imagination beflügelt sein lassen von dem, was sich da als Ungeheutes ergibt, sehen wir zurück auf den wahrhaften alten Abschnitt der Geschichte, den man imaginativ fassen muß. Und dann sehen wir erst im Vordergrunde sich erheben die römische Welt, die Welt des Mittelalters, die Welt, die bis zu uns herein geht. Und alle anderen Einteilungen - Altertum, Mittelalter und Neuzeit, oder wie sonst die Gliederungen heißen -, die rufen im Grunde genommen nur falsche Vorstellungen hervor. Dieses Bild allein, das ich jetzt vor Sie hingestellt habe, kann Ihnen, wenn Sie es tiefer und immer tiefer verfolgen, einen wirklichen Einblick geben auch in die Geheimnisse, die sich bis zum heutigen Tage in dem Werden der europäischen Geschichte ergeben haben. Davon dann morgen weiter.

Fifth Lecture

Among the ancient mysteries, that of Ephesus occupies a very special position. I have also had to remember this mystery of Ephesus in connection with that element of development in the history of the West which is linked to the name of Alexander. One can only understand the meaning of the more recent and older history if one considers the change that the mystery system, from which all older civilizations have emanated, has undergone from the Orient to the Occident, to Greece first. And this change consists in the following.

You see, if you look into all the older mysteries of the Orient, everywhere you get the impression that the mystery priests are able to reveal great, significant truths from their visions to their disciples. Indeed, the older one goes back in time, the more these priestly ways are able to evoke in the Mysteries the immediate presence of the gods themselves, the spiritual beings who govern the planetary worlds, who govern the earthly phenomena, so that the gods were really there.

The connection of man with the macrocosm revealed itself in various mysteries in a similarly magnificent way as I described to you yesterday for the mysteries of Hybernia and also for what Aristotle still had to say to Alexander the Great. Above all, however, what was present in all the ancient Oriental mysteries was that the moral, the moral impulses were not strictly separated from the natural impulses. When Aristotle pointed Alexander to the north-west, where the spirits of the water element were dominant, not only did a physical impulse come from there, as today the wind or other purely physical things come from the north-west, but moral impulses also came with the physical impulses. The physical and the moral were one. This could be because, through the knowledge given in these mysteries, man felt himself to be one with the whole of nature - he perceived the spirit of nature. There is, for example, a relationship between man and nature that lies in the time that elapsed between the lifetime of Gilgamesh and the lifetime of the individuality that he became in his next incarnation in the vicinity of the Mystery of Ephesus. It is precisely in that time that we still find a very vivid view of the connection between the human being and the spirit nature. This connection is as follows. Through everything that man came to know about the effect of the elemental spirits in nature, about the effect of the intelligent beings in the planetary processes, man came to the conviction: Out there I see the plant world spread out everywhere, the greening, the sprouting, the sprouting, the fruiting plant world. There I see the annual plants in the meadow, in the field, which grow up in spring and die again in autumn; there I see trees that have been growing for centuries, which grow bark and wood on the outside and reach far into the earth with their roots. Everything that takes root out there in the annual herbs and flowers, everything that grows with firm impulses into the earth, I once carried within me as a human being.

You see, today man feels when there is carbonic acid somewhere in a room, which has arisen through the breathing of people: I have exhaled this carbonic acid. - Man feels that he has breathed the carbonic acid into the room. Today man is, I might say, only in a slight connection with the cosmos. In the airy part of his being, in the air that underlies breathing and the other air processes that take place in the organism, man is completely in a living connection with the great world, with the macrocosm. He can look at the air he breathes out, at the carbonic acid that was inside him and is now outside. But just as man today - he does not do it, but he could - looks at the exhaled carbonic acid, so man, who was either initiated into the Oriental Mysteries or had absorbed the wisdom that flowed outwards from the Oriental Mysteries, looked at the whole plant world. He said to himself: "I look back in the development of the world to an ancient solar time. I still carried the plants within me. And then I let them flow out into the wide circles of the earth's being. But when I still carried the plants within me, when I was still that Adam Kadmon who encompassed the whole earth and the plant world with it, this whole plant world was still something watery and airy.

Man separated this plant world from himself. If you imagine that you would attain the size of the whole earth and then separate inwardly plant life, which now metamorphoses in the watery element, develops, passes away, grows up, becomes different, takes on different forms, then you would call up in your mind how it once was. And that it was once like this is what those who had taken up their education over there in the Orient in the time of Gilgamesh said to themselves. And when they looked at the plant growth in the meadows, they said to themselves: "We have separated the plants in an earlier stage of our development, but the earth has absorbed the plants. The roots were first given to them by the earth, as well as all that which is woody, which is the tree nature of plant life. - But that which is generally plant-like, man has separated from himself, and this has been taken up by the earth. Man felt an intimate kinship with all plant life.

Man did not feel the same kinship with the higher animal, because he knew he could only work his way up to earth by overcoming the animal formation, by leaving the animals behind on his path of development. He took the plants with him as far as the earth, then handed them over to the earth, so that the earth took them into its womb. He became the mediator of the gods for the plants on earth, the mediator between the gods and the earth.

Therefore such people, who now really had that great experience, which can be sketched quite simply (see drawing), felt: Man approaches the earth from the universe (yellow). The number is out of the question because, as I said yesterday, human beings interlock. He separates everything plant-like, and the earth takes up the plant-like and gives it the root-like (dark green lines). - Thus man felt as if he had enveloped the earth with the plant growth (red envelopment) and as if the earth had been grateful for this envelopment and had absorbed what man could breathe into it of watery-airy plant elements. And those who felt this felt themselves to be intimately related to the god, to the chief god of Mercury, with regard to this bringing of plants to the earth. Through this feeling that they themselves had brought the plants to earth, they came into a special relationship with the god Mercury.