The Christmas Conference

GA 260

Part I. Introductory

23 December 1923, Dornach

I. Introduction to the Eurythmy Performance

Today our guests from further afield who have already arrived make up the majority of those present at this opening performance of eurythmy. There is no need for me to speak particularly about the nature of eurythmy, for our friends know about this from various writings which have appeared in print. But especially since we are gathering once more for an anthroposophical undertaking I should like to introduce this performance with a few words.

In the first instance eurythmy is that art which has originated entirely from the soil of Anthroposophy. Of course it has always been the case that every artistic activity which was to bring something new into civilization originated in super-sensible human endeavour. Whether you look at architecture, sculpture, painting, or the arts of music or poetry, you will always find that the impulses visible in the external course of human evolution are rooted in some way in occult, super-sensible ground, ground we may seek in connection with the Mysteries. Art can only flow into human evolution if it contains within it forces and impulses of a super-sensible kind. But the present-day view of art arises in the main from the entirely materialistic tendency in thinking which has seized hold of Europe and America since the fifteenth century. And though a certain kind of scientific knowledge can flourish in this materialism, anything genuinely artistic cannot. True art can only come forth out of spiritual life.

Therefore it is as a matter of course that a special art has arisen out of the spiritual life of the Anthroposophical Movement. It is necessary to understand that art must be born out of the super-sensible realm through the mediation of the human being. Considering the descending scale stretching from the super-sensible realm down to externally perceptible phenomena, you find the faculty of Intuition at the top, at the point where—if I may put it like this—the human being merges with the spirit. Inspiration has to do with the capacity of the human being to face the super-sensible on his own, hearing it and letting it reveal itself. And when he is able to link what he receives through Inspiration so intensely with his own being that he becomes capable of moulding it, then Imagination comes about.

In speech we have something which makes its appearance in an external picture, though it is an external picture which is extraordinarily similar to Inspiration. We might say that what we bear in our soul when we speak resembles Intuition; and what lies on our tongue, in our palate, comes out between our teeth and settles on our lips when we speak is the sense-perceptible image of Inspiration.

But where is the origin of what we push outwards from our inner soul life in speech? It originates in the mobile shape of our body, or I could say in our bodily structure in movement. Our ability to move our legs as well as our arms and hands and fingers is what gives us as little children our first opportunity to sense our relationship with the outside world. The first experience capable of entering into the consciousness of our soul is what we have in the physical movement of arms, hands and legs. The other movements are more connected with the human being. But the limbs which we stretch out into the space around us are what gives us a sense of the world. And when we stretch out our legs in a stride or a leap, or our arms to grasp something, or our fingers to feel something, then whatever we experience in doing this streams back to us. And as it streams back, it seizes hold of tongue, palate and larynx and becomes speech.

Thus in his organism the human being is through movement an expression of man as a whole. When you begin to understand this you sense that what in speech resembles Inspiration can descend into Imagination. We can call back something that is a gift to our limbs, to our tongue, our larynx and our palate and so on, we can recall it and let it stream back, asking: What kind of feelings, what kind of sensations stream outwards in our organism in order to create the sound Ah? We shall always discover that an Ah arises through something which expresses itself in one way or another in the air, through a particular movement of our organs of speech; or an Eh in optical axes crossing over, and so on. Then we shall be able to take what has streamed out in this way and become a sound or element of speech, and send it back into our whole being, into our human being of limbs, thus receiving in place of what causes speech to resemble Inspiration something else instead, something which can be seen and shaped and which therefore resembles Imagination.

So actually eurythmy came into existence when what works unconsciously in the human being to transform his capacity for movement into speech is subsequently recalled from speech and returned to the capacity for movement. Thus an element which belongs to Inspiration becomes an element belonging to Imagination.

Therefore an understanding of eurythmy is closely linked with discovering through eurythmy how Intuition, Inspiration and Imagination are related. Of course we can only show this in pictures, but the pictures speak clearly.

Consider, dear friends, a poem living in your soul. When you have entirely identified yourself inwardly with this poem and have taken it into yourself to such an extent and so strongly that you no longer need any words but have only feelings and can experience these feelings in your soul, then you are living in Intuition. Then let us assume that you recite or declaim the poem. You endeavour, in the vowel sounds, in the harmonies, in the rhythm, in the movement of the consonants, in tempo, beat and so on, to express in speech through recitation or declamation what lies in those feelings. What you experience when doing this is Inspiration. The element of Inspiration takes what lives purely in the soul, where it is localized in the nervous system, and pushes it down into larynx, palate and so on.

Finally let this sink down into your human limbs, so that in your own creation of form through movement you express what lies in speech; then, in the poem brought into eurythmy, you have the third element, Imagination.

In the picture of the descent of world evolution down to man you have that scale which human beings have to reascend, from Imagination through Inspiration to Intuition. In the poem transformed into eurythmy you have Imagination; in the recitation and declamation you have Inspiration as a picture; and in the entirely inward experience of the poem, in which there is no need to open your mouth because your experience is totally inward and you are utterly identified with it and have become one with it, in this you have Intuition.

In a poem transformed into eurythmy, experienced inwardly and recited, you have before you the three stages, albeit in an external picture. In eurythmy we have to do with an element of art which had from inner necessity to emerge out of the Anthroposophical Movement. What you have to do is bring into consciousness what it means to achieve knowledge of the ascent from Imagination to Inspiration, and to Intuition.

The shorthand report ends here. The eurythmy performance began after a few more words on the actual programme.

The Christmas Foundation Conference was opened on 24 December. It had been preceded during the course of the year by a number of general meetings of the Anthroposophical Society in Switzerland at which the problems needing an early solution were discussed. The discussions had been particularly lively during the conference of delegates from the Swiss branches of 8 December 1923,20Reports of these meetings will be included in GA 259. See Note 2. and preparatory meetings had also taken place on 22 April and 10 June. A good many representatives of non-Swiss groups had been present as early on as the general meeting of the Verein des Goetheanum21See Rudolf Steiner Aufbaugedanken und Gesinnungsbildung, Dornach 1942. To be included in the Complete Works in the series ‘Zur Geschichte der anthroposophischen Bewegung und Gesellschaft’ (The History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society). on 17 June. These non-Swiss representatives had arrived in large numbers for the international meeting of delegates from 20 to 22 July,22Report to be included in GA 259. See Note 2. which had been devoted to the problems of rebuilding the Goetheanum and establishing it on a firm financial footing.

Dr Steiner had agreed to be present at these consultations but was not prepared to take the chair. His opinion had been sought quite a number of times, and he had emphasized above all the need for a moral basis. Rudolf Steiner und die Zivilisations-aufgabe der Anthroposophie contains many of the contributions he gave on that occasion. In the minutes of the meeting of 22 April we find the following:

‘Let me add a few words, not as a statement but simply in the realm of feeling, to what has been said so far today.

‘What we would look forward to in the outcome of the recent meeting in Stuttgart,23See Rudolf Steiner Awakening to Community, op cit. and also of today's meeting—and I hope similar meetings in other countries will follow—is that they should take a definite positive course, so that something positive can genuinely emerge from the will of the meeting. Mention has been made of the way the Anthroposophical Society is organized. But you see it has to be said that what marks the Anthroposophical Society is the very fact that it is not organized in any way at all. Indeed, for the most part the membership has wanted to have nothing to do with any organizing whatever, even on a purely human level. This was manageable to a certain degree up to a particular moment. But in view of the conditions prevailing now it is impossible to carry on in this way. It is necessary now to bring about a situation in which at least the majority of the membership can represent the affairs of the Society in a positive way, or at least start by following them with interest.

‘The other day I was asked what I myself expect from this meeting. I had to point out that it is now necessary for the Anthroposophical Society to set itself a genuine task, so that it can take its place as something, with its own identity, that exists beside the Anthroposophical Movement; the Society as such must set itself a task. Until this task has emerged, the situation we have been speaking about today will never change. On the contrary, it will grow worse and worse. The organization of the opposition exists and is a reality. But for the majority of members the Anthroposophical Society is not a reality because it lacks a positive task which could arise out of a positive decision in the will. This was the reason for calling the meetings in Stuttgart and here. In Stuttgart the delegates meeting could not decide on a task for the Society. Instead it sought a way out in the suggestion that the membership of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany should be divided into two parts in the hope that out of the mutual relationship between these two Societies something might gradually develop of a kind that was not forthcoming from the delegates meeting. Today's meeting should have the great and beautiful aim of showing how the Anthroposophical Society can be set a positive and effective task which can also win the respect of those on the outside. Something great could come about today if those present would not merely sit back and listen to what individuals are putting forward so very well, as has happened so far, but if indeed out of the Society itself, out of the totality of the Society a common will could arise. If it does not, this meeting, too, will have run its course to no purpose and without result.

‘I beg you, my dear friends, not to break up today without a result. Come to the point of setting a task for the Anthroposophical Society which can win a certain degree of respect from other people.’

The Christmas Foundation Conference for the founding of the General Anthroposophical Society was opened at 10 o'clock on the morning of 24 December. Dr Steiner greeted those present and introduced the lecture by Herr Albert Steffen on the history and destiny of the Goetheanum.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie-Darbietung

Meine lieben Freunde!

Da ja heute vor allem unsere auswärtigen Gäste, sofern sie schon angekommen sind, bei dieser eröffnenden Eurythmie-Vorstellung anwesend sind, so habe ich nicht nötig, im besonderen zu sprechen über das Wesen der Eurythmie. Es ist ja unseren Freunden bekannt aus den Darstellungen, die in unseren Gesamtschriften jetzt schon erschienen sind. Dagegen möchte ich nun gerade mit Rücksicht darauf, daß wir wiederum einmal zu einer anthroposophischen Unternehmung beieinander sind, auch diese Eurythmievorstellung mit ein paar Worten einleiten.

In der Eurythmie haben wir ja zunächst diejenige Kunst, welche aus anthroposophischem Boden ganz ursprünglich hervorgegangen ist. Nun war es ja immer so in der Welt, daß eine jede künstlerische Betätigung, die etwas Neues in die Zivilisation hineinbrachte, hervorging aus übersinnlichem Menschheitsstreben. Man kann hinschauen auf Architektur, auf Plastik, auf Malerei, auf das Musikalische, auf das Dichterische, überall wird man zunächst finden, daß die Impulse, die einem entgegentreten im äußeren Verlauf der künstlerischen Menschheitsentwickelung, doch in irgendeiner Weise zurückgehen auf okkulte, übersinnliche Grundlagen, Grundlagen, die wir geradezu im Mysterienwesen zu suchen haben. Die Kunst kann eben nur in die Menschheitsentwickelung hineinfließen, wenn sie Kräfte, Impulse übersinnlicher Art in sich hat. Und die Anschauungen, die man in der Gegenwart über die Kunst hat, sie sind ja im wesentlichen zusammenhängend mit der ganzen materialistischen Denkrichtung, die Europa und Amerika ergriffen hat seit dem 15. Jahrhundert. Aber wenn auch eine gewisse Art von wissenschaftlicher Erkenntnis in diesem Materialismus gedeihen kann, Künstlerisches, wirklich Künstlerisches kann da drinnen nicht gedeihen. Wirklich Künstlerisches kann nur hervorgehen aus spirituellem Leben.

Und deshalb darf man es als etwas, ich möchte sagen, Selbstverständliches ansehen, daß auch eine besondere Kunstrichtung hervorging aus dem spirituellen Leben der anthroposophischen Bewegung. Man muß sich ja darüber klar sein, daß das Künstlerische durch die Vermittlung des Menschen herausgeboren werden muß aus dem Übersinnlichen. Geht man von dem Übersinnlichen abwärts bis zu der äußeren sinnlichen Erscheinung, so hat man oben, möchte ich sagen, da, wo der Mensch zusammenfließt mit dem Übersinnlichen, die Intuition. Wenn der Mensch schon selbständig dem Übersinnlichen gegenübersteht, es vernimmt, es sich offenbaren lassen kann, dann hat man es zu tun mit der Inspiration. Und wenn der Mensch das Inspirierte so intensiv mit seiner eigenen Wesenheit verknüpfen kann, daß er es zu gestalten in der Lage ist, dann tritt die Imagination ein.

In der Sprache haben wir etwas, was allerdings im äußeren Bilde auftritt, aber in diesem äußeren Bilde der Inspiration außerordentlich ähnlich ist. Wir können schon sagen: Was wir eigentlich in der Seele tragen, wenn wir sprechen, ist der Intuition ähnlich; und was sich uns auf die Zunge, in den Gaumen, durch die Zähne auf die Lippen legt, indem wir sprechen, das ist das sinnliche Bild der Inspiration. Aber woher rührt dasjenige, was wir da von unserem inneren Seelenleben nach auswärts drängen in der Sprache? Es rührt her von unserer beweglichen Körpergestaltung, ich könnte auch sagen, von unserer Körpergestaltung in Beweglichkeit. Die Bewegungsmöglichkeit sowohl der Beine wie der Arme und Hände, der Finger, sie ist es, in denen der Mensch als ganz kleines Kind zunächst sein Verhältnis zur Außenwelt fühlt. Das erste Erlebnis, das ins Bewußtsein der Seele hereindringen kann, ist dasjenige, was wir in der physischen Bewegung der Arme, der Hände, der Beine haben. Die anderen Bewegungen sind mehr mit dem Menschen zusammenhängend; aber gerade diejenigen Glieder, die der Mensch sozusagen von sich ab in die Weite streckt, die geben ihm Weltgefühl. Und ebenso wie der Mensch sein Bein ausstreckt zum Gehen oder Springen, wie er seine Arme zum Greifen, seine Finger zum Fühlen ausstreckt, so strömt, was er da erlebt, wiederum zurück. Und beim Zurückströmen ergreift es Zunge, Gaumen, Kehlkopf und so weiter und wird zur Sprache.

Und so ist der Mensch in seinem Organismus der bewegte Ausdruck des ganzen Menschen. Und indem man anfängt, dies zu verstehen, empfindet man, wie das, was in der Sprache mehr der Inspiration ähnlich ist, heruntergehen kann in die Imagination. Wir können das, was ja ein Geschenk ist an unsere Gliedmaßen, an Zunge, Kehlkopf, Gaumen und so weiter wieder zurückholen, können es zurückströmen lassen, können in der folgenden Weise fragen: Welche Art von Gefühlen, welche Art von Empfindungen strömt im Organismus nach auswärts, so daß es ein A gibt? Wir werden immer finden: Ein A entsteht durch etwas, was in dieser oder jener Weise in der Luft sich ausdrückt durch eine besondere Bewegung unserer Sprachorgane oder in Augenachsen sich ausdrückt, die sich kreuzen, und so weiter. Und wir werden dann dasjenige, was auf diese Weise herausgeströmt ist und zum Laut, zum Sprachelemente geworden ist, wiederum zurücksenden können in den ganzen Menschen, in den Gliedmaßen-Menschen, und werden für das, was die Sprache der Inspiration ähnlich macht, etwas bekommen, was anzuschauen ist, was gestaltet ist, was der Imagination ähnlich ist.

Und so ist eigentlich die Eurythmie dadurch zustande gekommen, daß dasjenige, was unbewußt im Menschen wirkt, damit seine Bewegungsmöglichkeit zur Sprache wird, nun wiederum zurückgeholt wird aus der Sprache in die Bewegungsmöglichkeit. Und so wird ein inspiratives Element zu einem imaginativen Element gemacht.

Deshalb ist es schon mit dem Verständnis der Eurythmie verknüpft, daß man geradezu durch sie darauf kommt, wie zusammenhängen Intuition, Inspiration, Imagination. Man hat ja natürlich da nur die Bilder, aber die Bilder sprechen klar.

Nehmen Sie einmal, meine lieben Freunde, das Gedicht - das Gedicht, wie es bloß in der Seele lebt. Wenn der Mensch sich ganz innerlich identifiziert mit dem Gedichte, wenn er es, sagen wir, so sehr in sich aufgenommen hat, so stark in sich aufgenommen hat, daß er gar nicht mehr die Worte gebraucht, sondern die Empfindungen hat und diese Empfindungen in der Seele erleben kann: er lebt in der Intuition. Nehmen wir an, er kommt jetzt dazu, das Gedicht zu rezitieren oder zu deklamieren. Er versucht, in dem Vokalklang, in der Harmonie, in dem Rhythmus, in den konsonantischen Bewegungen, im Tempo, Takt und so weiter, er versucht also, in der Sprache rezitatorisch oder deklamatorisch das zum Ausdruck zu bringen, was in der Empfindung liegt: Inspiration ist, was so erlebt wird. Aus dem rein Seelischen, wo es im Nervensystem lokalisiert ist, wird durch das Inspirationselement die Sache hinuntergedrängt in Kehlkopf, Gaumen und so weiter.

Jetzt lassen wir es hinuntersinken in die menschlichen Gliedmaßen, so daß der Mensch in seiner eigenen bewegten Gestaltenbildung das zum Ausdrucke bringt, was Sprache ist, dann haben wir im eurythmisierten Gedicht das dritte Element: die Imagination.

Sie haben, ich möchte sagen, im Bild des Hinuntersteigens der Weltentwickelung bis zum Menschen jene Skala, die der Mensch wiederum zurückmachen muß: von der Imagination durch die Inspiration zur Intuition. In dem eurythmisierten Gedichte haben Sie Imagination, in der Rezitation und Deklamation Inspiration im Bilde, und in dem nur innerlich erlebten Gedicht, bei dem man nicht den Mund aufmacht, sondern es nur innerlich erlebt, sich selbst damit identifiziert, eins wird mit ihm, Intuition.

Und so haben Sie in der Tat, wenn Sie ein eurythmisiertes Gedicht vor sich haben, das Sie innerlich erleben, das rezitiert wird, die drei Stufen - allerdings in einem äußerlichen Bilde - vor sich. Wir haben es hier in der Eurythmie mit einem künstlerischen Element zu tun, das ganz aus innerer Notwendigkeit aus der anthroposophischen Bewegung hervorgehen mußte. Es handelt sich darum, sich zum Bewußtsein zu bringen, was es für eine Bewandtnis damit hat, Erkenntnis zu gewinnen zum Aufsteigen von der Imagination zur Inspiration, zur Intuition. —

Bis hierher wurde nachgeschrieben. Nach einigen auf das Programm bezüglichen Worten erfolgte die eurythmische Darbietung.

Am 24. Dezember wurde die Weihnachtstagung eröffnet, deren Programm wir hier einfügen [siehe Seiten 28/29]. Ihr waren im Laufe des Jahres einige Generalversammlungen der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft in der Schweiz vorangegangen, bei denen über die demnächst zu lösenden Probleme gesprochen worden war; besonders lebhaft war dies der Fall während der Delegiertenversammlung der Schweizer Zweige vom 8. Dezember 1923, aber auch schon vorbereitend bei den Versammlungen vom 22. April und 10. Juni. Bei der am 17. Juni stattgefundenen Generalversammlung des Vereins des Goetheanum waren bereits viele Vertreter der ausländischen Gruppen anwesend. In großer Zahl strömten sie heran zur internationalen Delegiertenversammlung, die vom 20. bis 22. Juli dauerte, den Fragen des Wiederaufbaus des Goetheanums gewidmet war und seine finanzielle Fundierung sichern wollte.

Dr. Steiner willigte ein, bei diesen Beratungen anwesend zu sein, nicht aber den Vorsitz dabei zu führen. Doch wurde er mehrmals gebeten, sich zu äußern. Er betonte vor allem die Notwendigkeit der moralischen Fundierung. In «Aufbaugedanken und Gesinnungsbildung» finden wir manche der damals von ihm gehaltenen Ansprachen. Im Protokoll der Versammlung vom 22. April finden wir unter andern die folgende Äußerung:

«Ich will nur mit ein paar Worten, nicht einmal ausdrücklich, sondern nur der Empfindung nach anknüpfen an dasjenige, was heute schon gesagt worden ist.

Von der kürzlich stattgefundenen Versammlung in Stuttgart und der heutigen hier - und ich hoffe, daß in andern Ländern solche nachfolgen werden — möchte man erwarten, daß sie in einer gewissen positiven Weise ablaufen, so daß wirklich aus dem Willen der Versammlung ein Positives hervorgeht. Es wurde darauf hingewiesen, wie die Gesellschaft organisiert ist. Nun muß man gerade sagen, daß ja die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft sich dadurch auszeichnet, daß sie nicht organisiert ist - in keiner Weise -, ja, daß der größte Teil der Mitgliedschaft von einem auch nur menschlichen Organisieren bisher nichts hat wissen wollen. Dies ging ja in einem gewissen Grade bis zu einem bestimmten Zeitpunkt. Aber angesichts der heutigen Verhältnisse ist es unmöglich, daß das also weitergehe. Es ist notwendig, daß wirklich so etwas auftritt, von dem es gelten kann, daß wenigstens für den größten Teil der Mitgliedschaft die Angelegenheiten der Gesellschaft als solche auch positiv von den Mitgliedern vertreten werden, mit Interesse verfolgt werden zunächst.

Als ich jüngst gefragt wurde, was ich selbst von dieser Versammlung erwarte, da mußte ich darauf hinweisen, wie es eben notwendig ist, daß die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft sich eine wirkliche Aufgabe setzt, so daß sie als Gesellschaft da ist, daß sie also etwas Besonderes noch ist neben der anthroposophischen Bewegung, also von Gesellschafts wegen sich eine Aufgabe setzt. Denn solange diese Aufgabe nicht da ist, werden die Verhältnisse, von denen heute gesprochen worden ist, niemals anders werden; im Gegenteil, sie werden sich immer mehr und mehr verschlimmern. Die Organisation der Gegnerschaft ist vorhanden, ist eine Realität; die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft ist aber für den größten Teil der Mitgliedschaft durchaus keine Realität, weil eigentlich keine positive Aufgabe, die aus einer positiven Willensentschließung hervorgehen könnte, da ist. Aus diesem Grunde wurden die Verhandlungen in Stuttgart und diese hier gehalten. In Stuttgart suchte man - weil sich die Delegiertenversammlung nicht entschließen konnte, der Gesellschaft eine solche Aufgabe zu setzen - gewissermaßen zu dem Auskunftsmittel zu greifen, die Mitgliedschaft dahin zu führen, daß sie sich in zwei Mitgliedschaften für die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft in Deutschland trenne, damit man hoffen könne, daß aus dem gegenseitigen Verhältnis dieser beiden Gesellschaften nun dasjenige nach und nach sich entwickele, was aus der Delegiertenversammlung nicht hervorgegangen ist. Die heutige Versammlung sollte das große, schöne Ziel haben, ein Beispiel dafür zu geben, wie man der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft als solcher eine positive wirksame Aufgabe setzen kann, die den Menschen draußen auch Respekt einflößt. Also es kann heute etwas Großes hier geschehen, wenn nicht bloß dem zugehört wird, was einzelne Persönlichkeiten in so schöner Weise ausführen, wie das heute geschehen ist, sondern wenn in der Tat aus der Gesellschaft selbst, aus dem Ganzen der Gesellschaft, ein gemeinsames Wollen hervorgeht. Sonst wird diese Versammlung eben auch resultatlos, ergebnislos verlaufen.

Ich bitte Sie, meine lieben Freunde, gehen Sie heute nicht ergebnislos auseinander, sondern kommen Sie dazu, der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft als solcher eine Aufgabe zu setzen, vor der die Menschen einen gewissen Respekt haben können.»

Die Eröffnung der Weihnachtstagung zur Begründungsversammlung der Allgemeinen Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft fand am 24. Dezember um 10 Uhr morgens statt. Dr. Steiner begrüßte die Anwesenden und sprach die einleitenden Worte zu dem Vortrag von Herrn Albert Steffen: «Aus der Schicksalsgeschichte des Goetheanums».

Address on the Eurythmy Performance

My dear friends!

Since most of our guests from out of town, insofar as they have already arrived, are present at this opening eurythmy performance today, I do not need to speak in particular about the nature of eurythmy. Our friends are already familiar with it from the descriptions that have appeared in our collected writings. However, in view of the fact that we are once again gathered together for an anthroposophical undertaking, I would like to introduce this eurythmy performance with a few words.

In eurythmy, we have first of all the art that originated entirely from anthroposophical ground. Now, it has always been the case in the world that every artistic activity that brought something new into civilization arose from supersensible human striving. One can look at architecture, sculpture, painting, music, poetry, and everywhere one will find that the impulses that confront us in the external course of human artistic development can be traced back in some way to occult, supersensible foundations, foundations that we must seek in the mysteries. Art can only flow into human development if it has forces and impulses of a supernatural nature within it. And the views that people have about art today are essentially connected with the whole materialistic way of thinking that has taken hold in Europe and America since the 15th century. But even if a certain kind of scientific knowledge can flourish in this materialism, art, true art, cannot flourish there. True art can only emerge from spiritual life.

And that is why it can be regarded as something, I would say, self-evident that a special art movement also emerged from the spiritual life of the anthroposophical movement. One must be clear that art must be born from the supersensible through the mediation of the human being. If one goes down from the supersensible to the outer sensory appearance, one has, I would say, intuition at the top, where the human being converges with the supersensible. When human beings independently encounter the supersensible, perceive it, and allow it to reveal itself, then we are dealing with inspiration. And when human beings can connect the inspired so intensely with their own being that they are able to shape it, then imagination comes into play.

In language, we have something that appears in the outer image, but is extremely similar to this outer image of inspiration. We can already say that what we actually carry in our soul when we speak is similar to intuition; and what is placed on our tongue, on our palate, through our teeth and on our lips when we speak is the sensory image of inspiration. But where does that which we express outwardly in language from our inner soul life come from? It comes from our mobile body structure, or I could also say, from our body structure in mobility. It is in the ability to move the legs, arms, hands, and fingers that the human being, as a very small child, first feels his or her relationship to the outside world. The first experience that can penetrate the consciousness of the soul is that which we have in the physical movement of the arms, hands, and legs. The other movements are more connected with the human being; but it is precisely those limbs that the human being stretches out, so to speak, from himself into the distance that give him a sense of the world. And just as humans stretch out their legs to walk or jump, just as they stretch out their arms to grasp and their fingers to feel, so what they experience flows back again. And as it flows back, it takes hold of the tongue, palate, larynx, and so on, and becomes speech.

And so, in their organism, humans are the moving expression of the whole human being. And when you begin to understand this, you feel how that which in language is more like inspiration can descend into the imagination. We can bring back what is a gift to our limbs, to our tongue, larynx, palate, and so on; we can let it flow back; we can ask in the following way: What kind of feelings, what kind of sensations flow outward in the organism so that there is an A? We will always find that an A arises from something that expresses itself in this or that way in the air through a particular movement of our speech organs or expresses itself in the axes of the eyes that cross, and so on. And we will then be able to send back what has flowed out in this way and become sound, become elements of speech, back into the whole human being, into the limb-human, and we will receive something for what makes speech similar to inspiration, something that can be seen, that is formed, that is similar to imagination.

And so eurythmy actually came about through the fact that what works unconsciously in the human being, so that its potential for movement becomes speech, is now brought back again from speech into the potential for movement. And so an inspirational element is made into an imaginative element.

That is why understanding eurythmy is linked to the realization of how intuition, inspiration, and imagination are connected. Of course, one only has the images, but the images speak clearly.

Take, my dear friends, the poem—the poem as it lives in the soul. When a person identifies completely with the poem, when he has absorbed it so deeply, so strongly, that he no longer needs the words, but has the feelings and can experience these feelings in his soul: he lives in intuition. Let us suppose that he now comes to recite or declaim the poem. He tries, in the vowel sound, in the harmony, in the rhythm, in the consonantal movements, in the tempo, beat, and so on, he tries, in other words, to express in recitative or declamatory language what lies in the feeling: inspiration is what is experienced in this way. From the purely spiritual, where it is located in the nervous system, the element of inspiration pushes the matter down into the larynx, palate, and so on.

Now we let it sink down into the human limbs, so that the human being expresses what language is in his own moving form, then we have the third element in the eurythmized poem: imagination.

In the image of the descent of world development down to the human being, you have, I would say, the scale that the human being must in turn climb back up: from imagination through inspiration to intuition. In the eurythmized poem you have imagination, in recitation and declamation you have inspiration in the image, and in the poem experienced only inwardly, where you do not open your mouth but only experience it inwardly, identifying yourself with it, becoming one with it, you have intuition.

And so, when you have a eurythmized poem in front of you that you experience inwardly, that is recited, you actually have the three stages in front of you, albeit in an external image. In eurythmy, we are dealing with an artistic element that had to emerge entirely from an inner necessity of the anthroposophical movement. It is a matter of becoming aware of what it means to gain insight into the ascent from imagination to inspiration, to intuition. —

This is where the transcript ends. After a few words about the program, the eurythmy performance began.

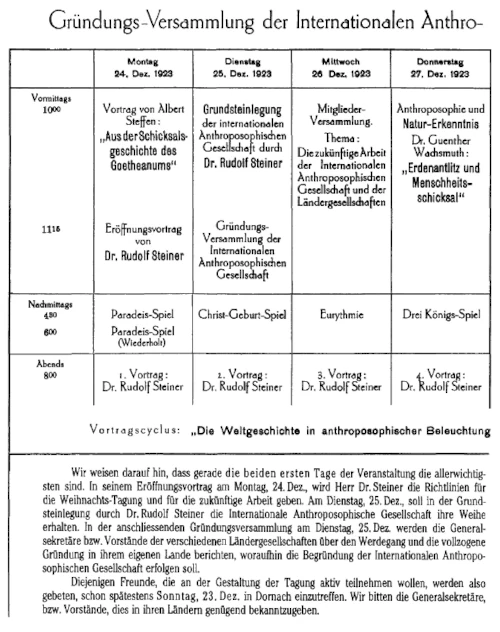

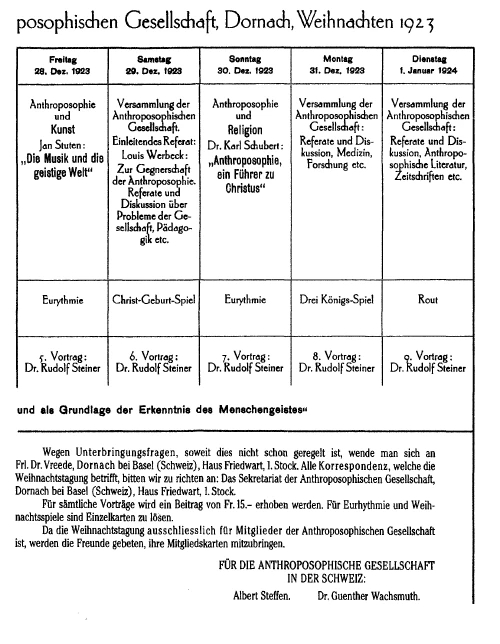

The Christmas Conference opened on December 24, and we have included the program here [see pages 28/29]. It was preceded in the course of the year by several general meetings of the Anthroposophical Society in Switzerland, at which the problems to be solved in the near future were discussed; this was particularly lively during the delegates' meeting of the Swiss branches on December 8, 1923, but also in the preparatory meetings on April 22 and June 10. Many representatives of foreign groups were already present at the general meeting of the Goetheanum Association on June 17. They flocked in large numbers to the international delegates' meeting, which lasted from July 20 to 22, was devoted to questions of rebuilding the Goetheanum, and sought to secure its financial foundation.

Dr. Steiner agreed to be present at these deliberations, but not to chair them. However, he was asked several times to speak. He emphasized above all the need for a moral foundation. In “Aufbaugedanken und Gesinnungsbildung” (Thoughts on Reconstruction and Attitude Formation), we find some of the speeches he gave at that time. In the minutes of the meeting on April 22, we find, among other things, the following statement:"I would like to follow up on what has already been said today with just a few words, not even explicitly, but only in terms of my feelings.

One would expect that the recent meeting in Stuttgart and today's meeting here — and I hope that others will follow in other countries — would proceed in a certain positive manner, so that something positive would truly emerge from the will of the assembly. It has been pointed out how the Society is organized. Now it must be said that the Anthroposophical Society is characterized by the fact that it is not organized — in any way — indeed, that the majority of its members have so far wanted nothing to do with even human organization. To a certain extent, this was the case until a certain point in time. But in view of today's circumstances, it is impossible for this to continue. It is necessary that something really does happen which means that, at least for the majority of the membership, the affairs of the Society as such are also represented positively by the members and followed with interest, at least initially.

When I was recently asked what I myself expect from this meeting, I had to point out how necessary it is for the Anthroposophical Society to set itself a real task, so that it exists as a society, so that it is still something special alongside the anthroposophical movement, so that it sets itself a task as a society. For as long as this task is not there, the conditions that have been discussed today will never change; on the contrary, they will become worse and worse. The organization of the opposition exists, it is a reality; but for the majority of its members, the Anthroposophical Society is by no means a reality, because there is actually no positive task that could arise from a positive resolution of will. For this reason, the negotiations in Stuttgart and these here were held. In Stuttgart, because the delegates' meeting could not decide to set the Society such a task, the attempt was made to resort to a kind of expedient, namely to lead the membership to divide itself into two memberships for the Anthroposophical Society in Germany, so that one could to set such a task for the Society, they sought, in a sense, to resort to the means of information, to lead the membership to divide itself into two memberships for the Anthroposophical Society in Germany, so that one could hope that the mutual relationship between these two societies would gradually develop what had not emerged from the delegates' meeting. Today's meeting should have the great and beautiful goal of setting an example of how the Anthroposophical Society as such can be given a positive and effective task that also commands respect from people outside the Society. So something great can happen here today, if we do not just listen to what individual personalities say in such a beautiful way, as has happened today, but if a common will actually emerges from the Society itself, from the whole of the Society. Otherwise, this meeting will also be fruitless and inconclusive.

I ask you, my dear friends, not to leave today without results, but to come to an agreement on a task for the Anthroposophical Society as such, one that people can have a certain respect for."

The Christmas Conference for the founding meeting of the General Anthroposophical Society opened at 10 a.m. on December 24. Dr. Steiner welcomed those present and gave the introductory words to the lecture by Mr. Albert Steffen: “From the History of the Goetheanum.”