The History of Art

GA 292

5 October 1917, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

10. Raphael: “Disputa” – “School of Athens”

The artistic representation of the imaginative-spiritual imagery of the fourth post-Atlantean period at the beginning of the fifth, which was becoming materialistic:

Today, I do not intend to begin these lectures on art history with a series of images, but rather to offer you an introduction based essentially on two images, which will be placed in the context of the recent history of human development. We will then continue with the art-historical epochs, as we did last year, following on from this introductory lecture.

The first image you see here is the one I would like to use as a starting point for our reflections today, and one with which you are very familiar: Raphael's so-called “Disputa.”

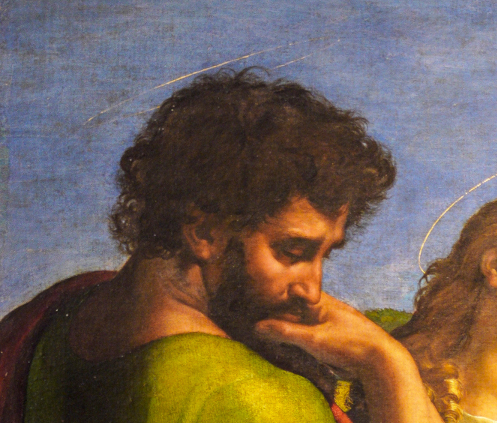

Let us briefly consider what this painting contains: at the bottom center of the painting, directly opposite us, we see a kind of altar with a chalice on it, which contains the host, the symbol of the sacrament of the altar. To the left and right, we see teachers of the Church; we recognize that they are teachers of the Church, popes, and bishops by their vestments; and we see that toward the center, the groups on the left and right become more animated, particularly in the hand movements of one figure—to your right, directly at the altar. It is precisely in her that we see that all these figures are participating in what is coming down from above. Then, when we look at the space behind this group near the altar, we see into the landscape and then — immediately above the landscape — in the upper half of the picture, we see masses of clouds beginning; we see, as it were, into the infinite horizon of space. And then we see in the middle, emerging from these masses of clouds, angelic geniuses floating on both sides of the dove, bringing the Gospels, brought out of the indeterminacy of the spiritual world. In the middle we see, represented by the symbol of the dove, the Holy Spirit. Above the Holy Spirit we have — clearly visible, but slightly set back, so that the Holy Spirit with the four angel figures carrying the Gospels would be slightly further forward in perspective — the figure of Christ Jesus and above the figure of Christ Jesus the figure of God the Father. So we have the Trinity above the chalice containing the Sanctissimum. On both sides of the figure of Christ, we now have a heavenly-spiritual group corresponding to the earthly group. We have saints on both sides of the figure of Christ; in the middle, immediately adjacent to the left and right of the figure of Christ, are the Madonna and John the Baptist; then other saints: David, Abraham, Adam, Paul, Peter, and so on. Further up in the clouds, we then have actual genius figures, spiritual individualities.

This picture we have here before us—there are, of course, much better reproductions—I would first like to place in the context of the history of human development.

First of all, let us realize the great difference that would arise for us if we were to put ourselves completely into the feelings of the time from which this picture was painted. If we were to put ourselves in the 16th century and compare this picture with the complex of feelings from which a painter today would paint something like this, we would have to say: Back then, in the 16th century, and in Rome, where Pope Julius II ruled, where Raphael, who had been called to Rome by Julius II in his mid-twenties, was working, at that time and in that place, this painting was a profound truth based on the human sensibilities that existed there at that time. Today, of course, one could paint something similar; but if this similar work were to have the same motif as this painting, it could not be true.

One must be very clear about such things, otherwise one will never arrive at a concrete view of human history, but will always remain with the abstract view of the legend—the bad legend—that is called human history in schools and universities today. All the details we can consider in order to understand this picture, to understand it artistically, to really understand it artistically, all the details are of a certain significance. Think of Raphael, this remarkable individuality Raphael, about whom we have often spoken here, coming to Rome at the beginning of the 16th century. He himself, Raphael, was in the body he was in at that time, in his mid-twenties; and we can safely assume that when he was mainly painting this picture, he was at the end of his twenties. At that time, he was completely under the influence and guidance of two old people who had already gone through great struggles in life and who had plans and ideas, ideas that were, one might say, the most far-reaching imaginable.

Let us be clear: until the papacy of Julius II, the Rome of that time was fundamentally very different from what it became under Julius II. The most prominent predecessors of Julius II were the Borgias. At the time of Alexander VI, we can say that Rome, as it had gradually developed over the years, was like a covering over the old ruins and rubble of the ancient world, with St. Peter's Basilica almost in a state of decay and unusable. However, these people were also inspired by a certain longing to revive the old artistic greatness of antiquity. But a remarkable change occurred between the Borgias and Julius II, precisely at the turn of the 15th to the 16th century. Beneath the suite of rooms and halls, which also includes the Camera della Segnatura, where the two frescoes we are discussing today are located, there is a suite of rooms and halls on the floor below, which Alexander VI had painted. It is strange that Julius II, Raphael's protector, seems to have avoided these rooms downstairs, which were the usual residence of his predecessors, as if the ghosts of cholera and the plague were constantly haunting them. He avoided them completely, not caring about the artistic, not about what had ever gone on there. Instead, he decided to have the rooms and halls on the floor above decorated in accordance with his ideas, as they can be seen today. We must consider this in the context of the fact that at the beginning of the 16th century, Pope Julius II had a completely different spirit than that which had prevailed among his predecessors.

Raphael's other protector was Bramante. He had a plan in his head for the new St. Peter's Basilica. Both Julius II and Bramante, as I have already said, were old men who had weathered the storms of life. They summoned this young man, Raphael, to Rome to serve them, to express in paint the powerful new ideas that were rumbling around in their heads, the new impulses that they believed should spread throughout humanity. We need to take a closer look at these impulses that were to spread from Rome to humanity from the beginning of the 16th century onwards. On the one hand, these impulses are closely connected with the development of the external Christian-ecclesiastical world and, in turn, with everything related to the institutions of this Christian-ecclesiastical world. On the other hand, they are intimately connected with the entire historical development of the West. Let us consider that it is extremely difficult for people today to put themselves in the place of the time from which, let us say, this painting, so often called the “Disputa,” emerged. And it is even more difficult for people today to put themselves in the shoes of those who lived in earlier centuries, even in the centuries when Christianity was already dominant. I have often mentioned that people today have the idea that human beings have always been the way they are today. But that is certainly not the case; especially with regard to the life of the soul, human beings have not always been that way. And when, nearly two millennia ago, the Mystery of Golgotha entered into human evolution, this Mystery of Golgotha was, in addition to what it became for the breadth of social human evolution, also something quite different from what it may be today in people's understanding. We imagine far too weakly what it meant that, around the time this picture was created, the following events befell humanity: first, the discovery of America at the end of the 15th century; secondly, the completely different social constitution of people that came about through the invention of printing; and finally, what arose with Copernicanism and Keplerianism in modern science.

Look at this picture. I said that if a painter were to paint it today, it would no longer be true in the same sense as it was then, for it could not be; because today one would not find souls for whom this picture would be as concrete as it was when it was painted, souls who have such a conception of the earth, which is conditioned by the fact that America has not yet been discovered. Souls who still look up at the clouds in sincere faith, in order to imagine what we today have to imagine in the spiritual world above the clouds, in a sense physically and spatially above the clouds. Such souls are no longer to be found today, not even among the most naive people. But we misrepresent the souls of that time if we do not believe that the content of this image was something that was absolutely concrete to these souls. Just think about it: what is the content of this image? Today, from our spiritual scientific point of view, we can find a name for what the content of this image is; we are familiar with speaking of imaginations as the first stage of visions ascending to the higher world. When we say that humanity up until the 16th century had an idea of the world, of the great spatial world in connection with the earthly world, which was absorbed into imaginations, then we are saying something correct. Imaginations were still something alive at that time; and Raphael painted the living imaginings that were present in people's souls. Worldview, world picture, were still something imaginative at that time.

These imaginations were driven out by the caustic power of Copernicanism, the discovery of America, and the art of printing. It was only from this time onwards that humanity replaced imagination with the external, objective conception of the entire structure of the world, with what we call imaginative knowledge, imaginative vision, so that – while modern man imagines: the sun is out there, the planets revolve around it, and so on — people did not have that at all; when they wanted to talk about something similar, they talked about imaginations. And this picture is a reflection of such imaginations. The centuries in which the imaginative vision of humanity gradually developed, reaching a certain conclusion in the 16th century with images such as these by Raphael, are the 16th, 15th, 14th, 13th, 12th, 11th, 10th, and back to the 9th century, but no further. If we want to go further back, we can no longer form any real ideas, even if we imagine the imaginative way in which people felt in the centuries mentioned, which we already find difficult enough to conjure up in our minds today.

If we want to imagine what Christianity became in the centuries before the 9th, we have to imagine Christian ideas as much more spiritual than we are usually inclined to do. Augustine took only what he needed from Christian ideas. But when you read Augustine today, you get a sense of what else lived in people's souls as a worldview and as an image of the connections between the world and human beings than later on and today. And you get particularly significant ideas when you read Scotus Eriugena, who taught during the time of Charles the Bald. One might say that in those earlier centuries before the 9th century, Christian thinking prevailed among those who elevated themselves to thinking at all; in those centuries, Christian thinking prevailed with highly spiritual ideas. One might say that when people formed a worldview in these earlier centuries, they included very little of what was provided by immediate sensory experience, but all the more of what was not provided by sensory experience, but was taken from the ancient clairvoyant vision of the world. And if we go back to the first centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha and follow Christian ideas, we find that these ideas are such that one can rather say: People at that time were interested in the heavenly Christ, the Christ as he was in the spiritual worlds; and what he had become down on earth they regarded more as an appendage. To seek Christ in the midst of spiritual beings, to think of him in connection with the supersensible-spiritual, that was the essential need; and that came from the old spiritual — albeit atavistic-spiritual — worldview. This worldview filled the old culture down into the third post-Atlantean epoch. At that time, the earth was truly thought of as a kind of appendage to the spiritual.

Now we must familiarize ourselves with an idea that is essential if we want to understand how humanity has actually developed to the present day. We must familiarize ourselves with the idea that European humanity needed to suppress spiritual ideas in order to develop its culture. One must not judge this with sympathy or antipathy; one must not judge it critically at all, but simply state the facts as they are; it was simply the fate, the karma of Europe, to arrive at the culture it had to arrive at. It was the fate of Europe to repress spiritual ideas, to hold them back, so to speak.

And so it came to pass that from the 9th century onwards it became increasingly clear and significant that Europe needed a Christianity that suppressed spiritual ideas. And one result of this necessity is the separation of the Church into the Greek Orthodox and the Roman Catholic Churches. At that time, the East separated from the West. This is something highly significant. The West has the destiny of holding back spiritual impulses toward the East. There they remain. And one really does not understand what is happening in human development if one is not clear that this European peninsula connected to Asia and Russia – I now count Russia as part of Asia – needed to push back the spiritual impulses towards the East from the 8th and 9th centuries onwards. They accumulated there, developed apart from Western and Central European life, and developed into today's Russia.

This is very significant. Let us keep this firmly in mind. Today, we are accustomed to no longer wanting to view things in context. And so an event such as the Russian Revolution seems like something that happened a few months ago — for whatever reasons one or the other might imagine — whereas in reality, the background to all this is that a certain spiritual life, which had gradually become invisible and intangible in the East over the centuries, had been pushed back, has accumulated and is now working in a still completely indefinable, chaotic way, so that the people who are involved in what is happening in the East really live in it as little as people swimming in the sea have sea water inside them — unless they are drowning; they have the sea water outside themselves. And so, too, what is working its way to the surface in the East in terms of spiritual impulses is still present in the spiritual realm. People are swimming in it and have little idea of what is pushing its way to the surface and has been pushed back to the East since the 9th century, so that it might be preserved there, so to speak, in order to undergo development in later times. The people who arose in the East, who gradually emerged in the East from the migration of peoples and other circumstances, had spiritual impulses pushed into their souls that the West and South of Europe and Central Europe could not use at first.

The West reserves something strange for itself. The East, without knowing it — most really important things happen in people's subconscious — the East, without really knowing it, remained strictly grounded in the Gospel principle: “My kingdom is not of this world.” Therefore, in the East, the physical plane still strictly follows the spiritual world, upward. The West was dependent on reversing the statement “My kingdom is not of this world” and thus making the kingdom of Christ a kingdom of this world. And then we see that Europe has the destiny of constituting the kingdom of Christ from Rome outwardly as an empire on the outer physical plane. One might say: From Rome, since the 9th century, the law was established: to break with the old saying, “My kingdom is not of this world,” but instead to constitute a worldly kingdom, which was to be the kingdom of Christ Jesus on earth, on the physical plane.

The Roman Pope gradually became the one who said: My kingdom is the kingdom of Christ; but this kingdom of Christ is of this world; and we must establish it in such a way that it is of this world, the kingdom of Christ. But there remained an awareness that this very kingdom is the kingdom of Christ, that this kingdom is the kingdom that should not be built on the mere principles of natural, external natural existence. People were aware that when they looked out into nature, when they saw everything that was created by the sun, by the morning and evening glow, by the stars, then they did not only have before them what their eyes could see, what their ears could hear, what their hands could grasp, but at the same time, in the vastness of infinite space, they had before them what was the spiritual kingdom. And everything that is here in the visible world is, in a sense, the last outflow, the last gulf of the spiritual world. And this visible world is only a whole when one is fully aware that it is the outflow of a spiritual world. This spiritual world is concrete; people have only lost sight of this spiritual world. It is hidden from people, but it is a reality, it is real. And when a person passes through the gate of death, and is particularly gifted for this, they enter the spiritual world. These people were therefore much more alive than we might be inclined to imagine today. When the dead, especially the gifted dead, had passed through the gate of death, they entered a world that we must imagine at present — penetrating the clouds, penetrating the stars, penetrating the planetary orbits. So it was something concrete that the souls of the dead form the upper group here in the picture. And the souls of the dead had the concrete mystery, the concrete secret of the Trinity in their midst, this concrete secret that is composed of the essence of the past — God the Father; of the essence of the present — Christ Jesus; of the essence of the future — the Holy Spirit.

But what unfolds there into the reality of time, if the present world, the world of the senses, is not to be a mere illusion, and if people want to live within this sensual world like animals, there must be signs in this sensual world on the physical plane of what floats and dwells invisibly in the spiritual world above the clouds. Those born later must have living signs of what those born earlier, who are now post-mortem souls, have direct insight into.

On the altar stands the chalice with the Sanctissimum, with the host. This host is not merely external matter for the people standing around it on the left and right, but this host is surrounded by its aura. And with the aura of this host, the forces that descend from the Trinity are at work. Such ideas, as they live in the minds of the Church Fathers, the bishops, the popes about the Sanctissimum on the altar, no longer exist in today's humanity. They have passed away in the course of time. And the moment is captured here in the image, in which it dawns on these people at the altar below: There is a mystery standing on the altar; something is hovering around the host. And this something is seen by the souls of the deceased, namely the blessed ones: David, Abraham, Adam and Moses, Peter, Paul — the deceased see it just as the souls here on the physical plane see the objects of the sensory world.

When we look at this lower part (197), with the Sanctissimum in the middle, then we have in what is down there, in a sense on the lowest level of the picture before us, what a man like Pope Julius II said: I want to establish such a kingdom, such an empire, in as much glory as is possible on earth from Rome – not a state, but an empire – to establish such a kingdom that in this kingdom, in this empire, things happen that are surrounded by such auras that the past lives on with its impulses in these auras. An empire, then, that is of this world, but which, in being of this world, is a sign, a signum, for what lives in the spiritual worlds.

Ideas of this kind will have been inspired in Julius II first by Bramante and then by the young Raphael. This is how it came about that the young Raphael was able to compose this painting. Julius II wanted this painting in his study, so to speak, in order to have it always before him like a sacred motto, that the empire should be founded from Rome, in which the most important things are the mysteries. But this empire should be of this world, of this world with the spiritual inclusion.

Only when one allows all these feelings we have just spoken of to affect one's soul does one get an impression of this picture, when one says to oneself: The spiritual world had been pushed back to the East since the 9th century, I would say in the same way as the clouds are pushed upward here, and now waited there until its time had come.

In contrast, the fifth post-Atlantean epoch was preparing itself — for the time being in the West — this fifth post-Atlantean epoch in which we still live and in which humanity will live for a long time, and which is entirely under the sign: My kingdom is of this world. And more and more, the kingdom of this fifth post-Atlantean epoch will be of this world. But into this kingdom, which is of this world, such things are placed, almost at the beginning, at the dawn of this fifth post-Atlantean epoch, under the influence of the old men Bramante and Julius II, by the youthful Raphael. The most important things in historical development happen unconsciously. And from unconscious but wise motives, Julius II brought Raphael to himself. We know that humanity has become younger and younger over the millennia; we know that at the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch it reached the age of twenty-eight, and is now “27 years old.” Certainly, Bramante and Julius II were old people; but they were not the ones who immediately brought into the world what only the youthful Raphael could bring with his body, which was precisely a youthful body and had the strength of a twenty-eight-year-old when he painted such things. These are significant spiritual backgrounds in the development of humanity.

And now let us imagine how Raphael painted in Rome with the idea you have just characterized, painting, as it were, the protest of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch against the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. It was not so, but let us imagine hypothetically that the following had been inspired in Raphael's soul: Raphael's soul had been confronted with this – it lived in his unconscious, but we can hypothetically place this unconscious before us – let us assume that Raphael's soul possessed the knowledge of what was to come as the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. The de-divinized, de-spiritualized world of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch was to come, in which humanity imagines the barren, desolate, icy world space, interspersed with suns and planets, imagines the desolate world space without spirit, imagines the earth itself without spirit, and attempts to construct an entire world through spiritless natural laws. Let us assume that this was placed before Raphael's soul: the reality of the spiritlessness of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. And Raphael's soul would have countered this with the impression: It must not be so; I want to throw into this spiritless age, which presents the icy universe with the spiritless nebula in the sense of Kant-Laplace's theory, the imagination of living spiritual existence. I want to fill, as much as I can, the imagination of this dreary natural-historical existence with the imaginations that arise from the ancient clairvoyant understanding of the world. - Suppose this is what it would have looked like in Raphael's soul. It looked like this in the subconscious of his soul; it even looked like this in the soul of Julius II.

Our age truly has no need to despise great minds such as Julius II or even the Borgias, as historical legend does; for history will have to pass very different judgments on our contemporaries, on the greatest figures of our age, than we have on the Borgias or Julius II or similar personalities of the past. People of the present simply do not have the distance to do so.

Raphael was born at the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, one might say, truly born as a child of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. He was indeed born out of this fifth post-Atlantean epoch, but as a soul protesting vividly against this epoch, wanting to bring into it in beauty what this epoch no longer wants to experience as truth; wanting to bring sensory spirituality into sensory materialism devoid of spirituality; wants to carry over into the fifth post-Atlantean epoch what ancient epochs have gained from spiritual vision. To bring what could be seen spiritually, translated into sensory images, into the realm of this world, a second realm in this world, into what is sensory but full of signs of the supersensible in its sensory nature – that was roughly Raphael's intention. And the truth of this is this image, a thoroughly true image, because it sprang from the living feeling of that time.

And now take the same time when the child of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch brings in all the imaginative spiritual imagery of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch and appears as the testament of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch in the fifth. Take this time. It is approximately the same time of year when a Nordic personality in Rome climbed the penitential staircase, of which it was said: if you climb so many steps, you perform such a godly deed that you are always remitted so many days of purgatory for each step you climb. In faith, in complete faith, this Nordic person in Rome, while Raphael was painting such images in the Camera della Segnatura in the Vatican, concerned for the salvation of her soul, climbed the stairs to save herself so many days in purgatory through this godly work. And as she climbs, this personality has a vision — a vision that shows her the futility of such works of piety as sliding up the stairs to save herself days in purgatory — a vision from which this personality cuts the tablecloth between herself and the world, which Raphael paints as the child of the fifth post-Atlantean age, like the testament of the fourth post-Atlantean age.

You know that this Nordic personality is Luther, Raphael's antipode. In Raphael, even if you only see it externally, everything is color and form, everything is spiritual imagery, everything is expression and sign of a supernatural world, but in sensual colors and forms, everything seeking form and creating form. And Luther, at the same time in Rome, with a soul full of song, full of poetry, but formless, living in the formlessness of the soul, rejecting this whole world that was around him in Rome. Just as in the 9th century the spiritual world of the East was pushed back, Luther pushes back for his Nordic world what had remained as a testament from the fourth post-Atlantean epoch in southern Europe. Luther pushes that back. And in the future we have the tripartite world before us: in the East, spirituality waits, held back; in the South, something that is like the testament of the fourth post-Atlantean period is taking shape, and is in turn held back and rejected. The musicality of the North takes the place of the colorful and form-rich testament of the South. Luther is the real antipode of Raphael. Raphael is the child of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, but in whose soul the entire content of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch lives on. Luther is the latecomer of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch; Luther is not a man of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch in which he lived; one might say that he was merely transferred from the fourth post-Atlantean epoch to the fifth. In his state of mind, Luther is entirely a man of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch. He thinks and feels like a person of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch; but he has been transported into the fifth post-Atlantean epoch and lives out what is now to resound into the fifth post-Atlantean epoch with its barren sensuality, with its mere natural history, with its ice fields of spiritual emptiness. Raphael is the person of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch with the soul content of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch; Luther is the person who — because he has only been transported from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean epoch — stands with his soul in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch, who rejects everything external and instead wants to build the impulses of the human soul on something that has nothing to do with the external work and external actions of human beings, on something that is based solely and exclusively on a formless inner connection between the human soul and the spiritual world, on mere faith.

Just imagine if a painter wanted to paint a picture based on Lutheranism that was as true as Raphael's painting based on southern Catholicism — what would he paint? He would paint a figure of Christ, like Albrecht Dürer painted him; or he would paint a devout person, and in the physiognomic expression one would recognize that there is something alive in the soul that has nothing at all in common with the sensual environment and the objects of the sensual environment in which this soul is placed.

Thus, one era follows another. Today, people have completely different ideas. You can see this from the fact that today, paintings are made in which Christ is depicted as a human being among other human beings: “Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest” — and the like, as human as possible:

Here in our picture (197) you have the group of bishops, of church teachers, at the bottom; in the middle, the mere sign, the symbol. But that points to a supersensible world; the Trinity is concretely present there.

We will now focus particularly on the “Trinity.” We have another picture that depicts this Trinity alone:

You see God the Father above, the Spirit and the Son below. You see these three elements highlighted as the concrete content of the future, the present, and the past. The worldview of the time would not have been able to mix what lived in the immediate perception of the gifted souls of the dead with what is the external sensory world. But in order to truthfully depict what he had to portray in accordance with the ideas of the time, Raphael needed a free view out into the vastness of natural space. He had to express in the picture, as it were, that the mere sensuality of what fills space is not true; but as truth, this enters into space. That is why you have below—you can still see the strip of the horizon—the wide perspective extending into infinity. In a sense, this expresses the protest against depicting nature merely in the sensual sense of today.

Raphael did not arrive at the composition of this painting easily. To illustrate this, let us look at two of the sketches that Raphael drew first, from which the painting gradually emerged:

We must imagine the whole process as follows: Raphael came to Rome around 1507 or 1508, received the commission from Julius II, and then tried to first put into the painting what he already had in mind. Gradually, he was instructed by Julius II; gradually, he began to understand the relationship between space, nature, and the supernatural and sensual groups of humanity as it should be.

The other sketch, too,

which deals more with the lower part of the first sketch, still shows a completely unfinished style. You can see that he has not yet come to terms with it. What Raphael had to come to was to think correctly, in the spirit of the time, about the relationship between the spiritual world and nature. In ancient times, up until the 9th century, people still had a clear idea of the connection between the human past and the natural present. People before the 9th century — as grotesque as it may sound to today's humanity — did not think that when something happened to them, it happened by chance; no, they knew that when something happened to them, it happened because the dead with whom they were karmically connected lived in the events in which they were entangled. Before the 9th century, the dead stood before people in the events that surrounded them. Then such ideas gradually faded away, and what remained was what I have characterized to you as entering the 16th century.

But if we go back once more to this 9th century, we also come to the point where we must imagine that There was no temporal separation between nature and the spiritual world for these ancient peoples. Nature was, as it were, the continuation downward — before the ninth century, I say — the continuation of the spiritual world. But Greek culture had already worked into this worldview what human beings can bring in through their own thinking, through their self-centered ego. What Raphael painted there — he himself expressed it by placing a female figure from the symbolism of the time above this painting, which a later period called “Disputa,” although certainly nothing is being disputed, bearing the motto: DIVINARUM RERUM NOTITIA = What is written of divine things. Basically, before the 9th century, the worldview was still “what was known of divine things,” and nature was only like a gulf into which the divine world stretched down, and in which man then found himself.

This whole view had, as I said, been pushed back to the East, and its echo remained in the imaginations that Raphael painted like a testament from the fourth post-Atlantean age. At that time, people wanted to establish the kingdom of Christ from the South, on Earth, on the physical plane itself, as a power empire. Pope Julius II, like other similar personalities, did not write what he actually wanted on his banner. He really wanted to establish what could not be established because Luther came, because Calvin and Zwingli came. He wanted to establish a kingdom of Christ that was of this world. But he should not have said that. Such personalities are usually regarded as somewhat esoteric. Julius II should not have marched through Italy like a military commander in order to first harness the Italian peoples into the empire, into the new Roman Empire. He said something else. He said he was marching through Italy as a military commander to liberate the Italian peoples. That is what one says. Even in later times, people say that this or that must be done to liberate the peoples, when in fact they want something completely different. But even back then, many people believed that Julius II had marched through Italy to liberate the individual Italian peoples. Of course, that never occurred to him; any more than it occurs to Woodrow Wilson, for example, or could ever occur to him, to liberate any peoples.

Now, you see, we have this powerful divide, I would say, between the two eras: the holding back of this southern element. The division in worldview had been preserved from ancient Greek times. It had been made clear: what nature sifts through from the living deeds of the dead is no longer visible when man develops what he has unfolded from the spiritual powers of his own breast, from his own soul; then he does not receive DIVINARUM RERUM NOTITIA, not that “which is written down of divine things,” but rather CAUSARUM COGNITIO, “the knowledge of what causes exist in the immediate world.” But he should be careful not to try to interpret the whole of nature. If one wants to get an idea of nature—Julius II would have proclaimed to the world in thunderous words, had he been prompted to do so—if one wants to get an idea of nature and shows in it that the sun rises, that there is morning and evening red, that there are stars, as the people of the fifth post-Atlantean age do, then one is lying. In truth, you are then denying that the Trinity is within it, that the souls of the dead are within it, that there really is something within it that you express imaginatively by looking around and depicting the souls of the dead, David, Abraham, Paul, Peter, and the Holy Trinity. You leave out what is really in nature, the ancient eons, because you only put the most recent eon in there! — That is what he would have said. Do you want to rely on yourselves? If you want to develop only what you can develop through human powers, as they are bound to the physical body, then you will only obtain an external science of the external nature of man, a science only insofar as man is not connected with the infinite vastness of the world, but is confined, interwoven in the limits he sets for himself.

That must have been roughly what Julius II said to Raphael: If you want to paint what man can know about man today through his own soul power, then you must not paint man with the infinite perspective of nature, but you must enclose man, however ingenious, however wise he may be, within the limits he has set for himself. You must enclose him in halls, show him here in these rooms from which the world is ruled—for Julius wanted to paint the world as it would have been if Luther had not come, or Zwingli, or Calvin. — If you want to paint the world as it should be ruled from these rooms, then paint on one side what is real in the vastness of nature, and on the other side what man can find if he searches only with the powers of his own soul. But then you must not paint nature, but man within the limits he sets for himself.

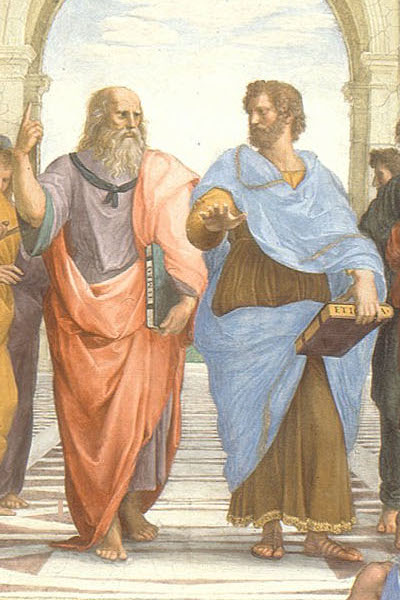

This is what we have when we let the opposite image, the one on the other side, the so-called “School of Athens,” sink in.

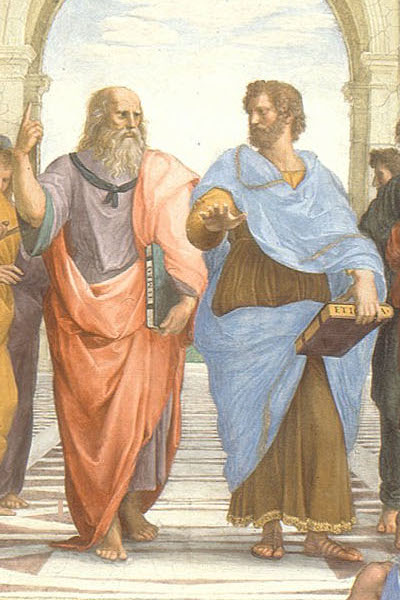

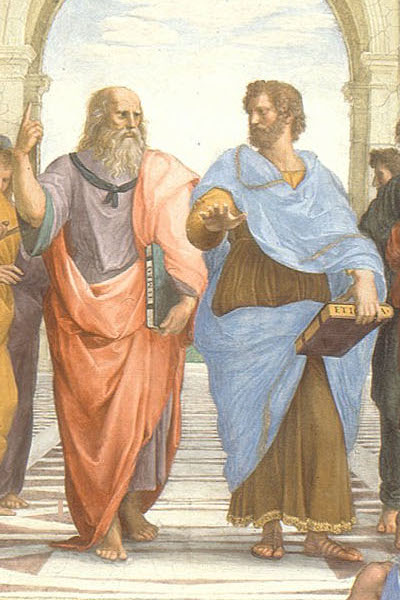

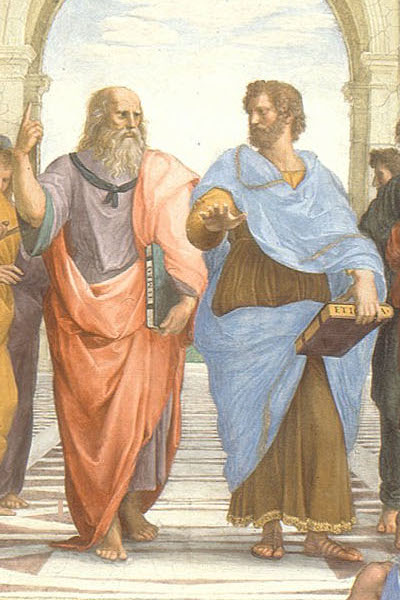

Over time, people have painted all sorts of things over this picture, which was often—but only later—called “The School of Athens.” For example, ‘Etica’ is painted on the book held by the man standing in the middle, and “Timeo” on the book held by the other man. All of this was painted over later. The painting has been damaged in many places, and of course today in Rome it is no longer possible to get a proper idea of what the painting originally looked like. In Raphael's time, it was never called “The School of Athens”; that name came later, but then people developed theories about it. Essentially, we have to imagine that The world becomes true according to the other image (197) when one looks into the infinite vastness of space and imagines nature not merely as perceptible, but permeated by all that is in eternity and temporality, permeated also by those who have passed through the gate of death. What man knows from his own soul, he must present in such a way that, if they were all together, these wise men, as here (202), he is represented with the knowledge of the heavenly, which can be found by relying only on oneself, in the one personality pointing upwards with his hand (203). There is no need to commit the unartistic folly of seeing Plato in this figure.

One can imagine that what the figure with the hand pointing upwards symbolizes is conveyed in the words spoken — indicated by the hand movement — by the figure on the right. The personality on the right begins to speak, so that it seems as if it is being expressed in words. But everything that comes from the human soul itself only becomes true when it is presented in the enclosed space, when the person remains within themselves. If the human being seeks an image of nature from within himself, he finds nothing but an image of abstract nature, as presented in the Copernican world view, not an image of concrete nature.

Thus, following the commission of Julius II, Raphael juxtaposed the divine with what can live in the human soul at the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch through this soul itself. Here we have grouped together everything that is secular science, but secular science that rises up to the comprehension of the divine, to the intellectual comprehension of the divine. If one analyzes this group, one finds the so-called seven liberal arts: grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music. Then, culminating in expression, you can find, as in the one who applies all worldly science to the divine, and in the one who expresses it for the human word, how the contrast between the beholder and the speaker lives there; this emerges from the image itself. Unartistic, amateurishly learned chatter has seen the whole of Greek philosophy in this image. That is not necessary. That has nothing to do with the work of art. But all of that has to do with the work of art we have been discussing today and what we have just hinted at, for it shows us that this picture also reflects a true human feeling in the spirit of that time. Feelings about what the soul, when left to itself in its cognition, finds about human beings.

We still have details of this picture that we want to show:

If you were to take a closer look, you would find that all of the figures on the right are connected to the central figure, who is about to speak; here on the right (205) we also have everything that is based more on inspiration, while on the left (204) we have more of what is based on imagination and the like.

Now we have another picture of the central figures:

So it is the contrast between the viewer and the speaker. Let us be clear that we can only understand the present if we try to look more and more into the past, as we can do when we perceive such images in an artistic sense. Our time is a time in which many things are returning. In our time, certain moods are returning to Europe, to Central Europe, especially in Northern Europe, and in Western Europe in general, certain moods are returning that are karmically connected with the 9th century of European development. People today do not yet understand this clearly; indeed, not only do they not understand it clearly, they do not understand it at all. What is happening today is in many ways arising from the necessity to take the opposite spiritual measure to that which had to be taken for the fate of Europe in the 9th century. Just as the spiritual world was held back in the East at that time, so now it must be incorporated into the physical plane again. The moods of the 9th century AD are returning in the present time in Western Europe, in Central Europe, in Northern Europe. In Eastern Europe, out of the chaos, out of the terrible chaos and muddle, something like moods will develop that will mysteriously echo the 16th century. And only from this harmony of the moods of the 9th and 16th centuries will the mystery arise that can shed some light on that which today's humanity must have illuminated if it wants to rise to some understanding of development.

It is very remarkable to see how, in the 16th century, everything that was most mysterious and enigmatic for nature, humanity, and God was made visible to the outside world through art. We find the sacred mystery of the Trinity presented before our souls in one of the most significant images in the world. And its antipode immediately arises: the Protestant-Evangelical mood, which wants nothing to do with the idea that these sacred mysteries should somehow be brought into the open. In Herman Grimm, a truly Nordic Lutheran spirit, you will find passages where he speaks of how what people today think about Christ is preserved in the innermost depths of his soul — is the exact opposite of the mood that Raphael painted into the world.

You see, back then, at the beginning of the 16th century, there was the Reformation, and further development through a Reformation had, in a sense, become worldless, even in Rome, even in the sphere of Julius II, the Pope. But how? — It had become so worldless that people wanted to reflect on the fact that the supersensible world is visible, but only through human development. And so — as Herman Grimm correctly discovered — Pauline Christianity, indeed the figure of Paul himself, became a particular problem for Raphael and his circle. One can say: Until well into the 16th century, Christianity was much more permeated by what might be called Petrine Christianity, Peter, who still saw the supersensible and sensible worlds as undivided, in which the sensible still perceived the supersensible within it, and the supersensible the sensible. But the supersensible world was disappearing. People were aware of this right up until the 16th century. Then what lived in Paul, the vision, the mystery of Damascus, and with it the figure of Paul himself, became a problem. That is why Raphael, in his later development, tried to capture the figure of Paul, to place the figure of Paul in his most diverse paintings. And one can say: From the south, a reformation arose that sought to convey Paul's vision of the world as I have now described it, as it lived in the paintings of Raphael, which were created under the inspiration of Julius II.

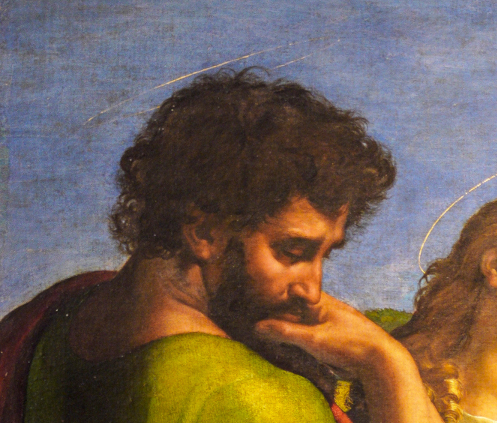

Paul was a problem for him. One senses this when one follows the figure of Paul in other paintings by Raphael. In “Saint Cecilia,” you see a pictorial expression of the music of the spheres:

It is, of course, an imprecise expression. In the left corner, meaningfully, is the figure of Paul. Raphael studies the figure of Paul pictorially. Again and again, Paul becomes a problem for him. Why? — Because Paul seeks, out of his human individuality, to see, or at least to come to see, to enter into seeing. Here, we see it in his whole posture, in his gesture: Paul, as a seeker, participating in what is self-evident to others. He develops both sides; therefore, when it comes from him, what is to happen as Christian proclamation is different. How Paul understands—you see it here; how Paul teaches—that became a problem for Raphael.

Now we have another picture: Paul speaking in Athens.

You see, Raphael studied Paul. What did Paul become to him? The hero, the spiritual hero of the Reformation, which should have succeeded from the south, but did not. This was then held back, and later Jesuitism from the south took the place of the Reformation. More on that another time. Paul should have brought about what Julius II had envisioned as a kingdom of Christ on earth.

And now, really, really take in the two Pauline heads that we have now:

These are heads that Raphael studied in order to depict in them the physiognomy that looks into the mysteries of the Christian world, into the spiritual mysteries, and that can proclaim these spiritual mysteries to the outside world through the word; and in Paul we have the link between the world that is recognized as the world of causes and the world that is accessible only to gifted vision, the supersensible world. Paul, seeing and teaching, the link between the world of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch and the ancient spiritual time. And take with you what Raphael studied in Paul's physiognomy, in Paul's gestures, right down to the movements of his fingers – here just the raised arm – take that with you and now look again at the figure in the so-called “School of Athens”:

Compare the two Pauline heads we have seen (235, 236) with the head here (203), on the right from your perspective, and you have the personality in whom seeing has become word, I would like to say: the Paul who has grown beyond the vision of the event of the mystery of Damascus, who has become the spokesman of Christianity, who makes his pact, a compromise with what can be found in the Causarum Cognitio, when one rises from the knowledge of the earthly world of causes to what man can experience of divine things. And then you will sense something of what I would call the “signature” that hovers through the Camera della Segnatura itself when you look from the painting that was later called “The Disputation” to the one called “The School of Athens.” In “The Disputation,” truth, spiritual truth, is found in a space filled with nature; if you turn your gaze to the other, opposite wall, you encounter his companion, the observer, the teaching Paul, who points to the worldly scholarship from which everything that the human soul can find within itself can spring. If you look at the fresco that is the so-called “School of Athens,”

so that the central figures represent souls whose content is depicted in the fresco opposite:

Then you have roughly the connection. Take one wall—everything that is inside the souls, which you cannot see, of which you only see the outer physicality, is on the other, opposite wall, which is the fresco of the so-called “Disputa.”

I would like to say: if one could look into the souls of these two people painted on one wall, one would see what lives in the souls of these two people on the opposite wall, in the so-called “Disputa” fresco. More on that another time.

10. Raffael: «Disputa» - «Schule Von Athen»

Die künstlerische Darstellung der imaginativ-spirituellen Bildhaftigkeit des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraums im Beginn des materialistisch werdenden fünften:

Ich denke heute nicht daran, durch eine Anzahl von Bildern diese kunstgeschichtlichen Vorträge einzuleiten, sondern als Einleitung Ihnen eine Betrachtung zu geben, die wesentlich nur an zwei Bilder anknüpfen soll, und zwar sollen diese beiden Bilder in die neuere Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit hineingestellt werden. Kunstgeschichtliche Epochen wollen wir dann, wie wir es im vorigen Jahre gemacht haben, weiter an diesen Einleitungsvortrag anknüpfen.

Sie sehen hier als erstes das Bild, an das ich vorzugsweise unsere heutigen Betrachtungen zunächst anknüpfen will und das Sie gut kennen, Raffaels sogenannte «Disputa».

Wir vergegenwärtigen uns ganz kurz, was dieses Bild enthält: Wir sehen unten in der Mitte des Bildes unmittelbar uns gegenüber eine Art Altar mit dem Kelche darauf, welcher die Hostie, also das Symbolum des Altarsakramentes enthält. Wir sehen zur Linken und zur Rechten Kirchenlehrer; wir erkennen, daß sie Kirchenlehrer, Päpste, Bischöfe sind, an ihrer Gewandung; und wir sehen, daß gegen die Mitte zu die Gruppen links und rechts bewegter werden, namentlich an der Handbewegung der einen Persönlichkeit — von Ihnen aus rechts unmittelbar am Altar. Gerade an ihr sehen wir, daß alle diese Persönlichkeiten teilnehmen an dem, was von oben herunterkommt. Wir sehen dann, wenn wir den Raum hinter dieser nahe dem Altare befindlichen Gruppe betrachten, in die Landschaft hinein und sehen dann - unmittelbar oberhalb der Landschaft - in der oberen Hälfte des Bildes Wolkenmassen beginnen; wir sehen gewissermaßen in den unendlichen Horizont des Raumes hinein. Und dann sehen wir in der Mitte aus diesen Wolkenmassen heraus durch engelartige Genien, die auf beiden Seiten der Taube schweben, die Evangelien gebracht, gebracht aus dem Unbestimmten der geistigen Welt heraus. In der Mitte sehen wir, dargestellt durch das Symbolum der Taube, den Heiligen Geist. Über dem Heiligen Geist haben wir — deutlich zu sehen, aber etwas zurückliegend, so daß also der Heilige Geist mit den vier Engelfiguren, die die Evangelien tragen, etwas weiter nach vorn liegen würde in der Perspektive —, die Figur des Christus Jesus und über der Figur des Christus Jesus die Figur des Gottvaters. Wir haben also die Dreifaltigkeit über dem Kelch, in dem sich das Sanktissimum befindet. Zu beiden Seiten der Christus-Figur haben wir nun entsprechend der irdischen Gruppe eine himmlisch-geistige Gruppe. Wir haben Heilige zu beiden Seiten der Christus-Figur; in der Mitte, unmittelbar anstoßend links und rechts an die Christus-Figur die Madonna und Johannes den Täufer; dann andere Heilige: David, Abraham, Adam, Paulus, Petrus und so weiter. Noch weiter nach oben gehend in den Wolken haben wir dann eigentliche Genien-Figuren, geistige Individualitäten.

Dieses Bild, das wir hier vor uns haben - es gibt natürlich viel bessere Nachbildungen -, möchte ich zunächst etwas in die Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit hineinstellen.

Vor allen Dingen machen wir uns zunächst den großen Unterschied klar, der sich für uns ergeben würde, wenn wir uns ganz in die Empfindungen der Zeit versetzten, aus der heraus dieses Bild gemalt worden ist. Wenn wir uns in das 16. Jahrhundert versetzen und dieses Bild mit dem Empfindungskomplex vergleichen, aus dem heraus etwa heute ein Maler so etwas malen würde, müßten wir sagen: Damals, im 16. Jahrhundert, und in Rom, da der Papst Julius II. an der Stätte herrschte, wo der in der Mitte seiner Zwanzigerjahre durch Julius II. nach Rom berufene Raffael wirkte, in jener Zeit und an jener Stätte war aus den menschlichen Empfindungen, die damals dort lebten, heraus, dieses Bild eine tiefe Wahrheit. Heute könnte man selbstverständlich etwas Ähnliches malen; wäre aber dieses Ähnliche in der Motivgestaltung so wie dieses Bild, so könnte es keine Wahrheit sein.

Solche Dinge muß man sich nur ganz klar machen, sonst wird man niemals zu einer konkreten Betrachtung der Menschheitsgeschichte kommen, sondern immer bei der abstrakten Betrachtung der Legende - der schlechten Legende - verbleiben, die man heute in den Schulen und an den Universitäten Menschheitsgeschichte nennt. Alle Einzelheiten, die wir ins Auge fassen können, um dieses Bild zu verstehen, künstlerisch zu verstehen, es wirklich künstlerisch zu verstehen, alle Einzelheiten sind von einer gewissen Bedeutung. Denken Sie, daß Raffael, diese merkwürdige Individualität Raffael, über die wir ja auch hier öfter gesprochen haben, dazumal im Beginne des 16. Jahrhunderts nach Rom kommt. Er selbst, Raffael, ist in dem Körper, in dem er damals war, in der Mitte der Zwanzigerjahre; und man kann ruhig annehmen, daß er, als er hauptsächlich an diesem Bilde gemalt hat, am Ende der Zwanzigerjahre war. Er war damals ganz unter dem Einflusse, in der Direktive von zwei alten Leuten, die bereits große Kämpfe des Lebens durchgemacht und die Pläne und Ideen hatten, Ideen die alle, könnte man sagen, die denkbar weittragendsten waren.

Machen wir uns nur einmal klar: Bis in die päpstliche Vorgängerschaft Julius II. war das Rom der damaligen Zeit doch im Grunde ein ganz anderes als es dann durch Julius II. wurde. Am hervorstechendsten sind ja aus der Vorgängerschaft Julius II. die Borgias. Zur Zeit Alexanders VI., können wir sagen, war Rom eigentlich, so wie es sich allmählich im Laufe der Jahre herausgebildet hatte, wie überdeckend das alte Ruinen- und Trümmerwerk der antiken Welt, die Peterskirche nahezu am Verfall, unbrauchbar geworden. Allerdings waren auch diese Leute schon von einer gewissen Sehnsucht beseelt, die alte künstlerische Größe der Antike wieder auferstehen zu lassen. Aber es geschieht ein merkwürdiger Einschnitt gerade zwischen den Borgias und Julius II., gerade vom 15. ins 16. Jahrhundert herüber. Unter der Zimmer-und Säleflucht, zu der auch die Camera della Segnatura gehört, in der sich die beiden Fresken befinden, von denen wir heute sprechen, also im Geschoß darunter ist eine Flucht von Zimmern und Sälen, welche Alexander VI. hat ausmalen lassen. Es ist ja doch merkwürdig, daß Julius II., der Protektor von Raffael, diese Zimmer, die da unten sind, die der gewöhnliche Aufenthaltsort seiner Vorgänger waren, so gemieden zu haben scheint, als wenn da drinnen fortwährend die Gespenster der Cholera und der Pest herumgingen. Die hat er ganz gemieden, hat sich nicht bekümmert um das Künstlerische, nicht um das, was da jemals vorgegangen war. Dagegen hat er beschlossen, im Sinne seiner Ideen die Zimmer und Säle des darüberliegenden Geschosses herrichten zu lassen, wie sie jetzt eben zu sehen sind. Wir müssen das durchaus schon im Zusammenhange damit denken, daß im Beginne des 16. Jahrhunderts aus dem Kopfe des Papstes Julius II. heraus ein ganz anderer Geist waltet als der Geist, der früher unter seinen Vorgängern gewaltet hat.

Der andere Protektor des Raffael war Bramante. Er hatte in seinem Kopfe den Plan zu der neuen Peterskirche. Beide, sowohl Julius II. wie Bramante, sagte ich schon, waren alte Leute, die die Stürme des Lebens hinter sich hatten. Diesen jugendlichen Menschen, den Raffael, beriefen sie nach Rom; der sollte ihnen dienen, malerisch zum Ausdruck zu bringen, was in ihren Köpfen an neuen Ideen mächtig rumorte, an neuen Impulsen, von denen sie dachten, daß sie durch die Menschheit gehen müßten. Man muß sie sich etwas näher anschauen, diese Impulse, die da von Rom aus in die Menschheit eindringen sollen vom Beginne des 16. Jahrhunderts ab. Diese Impulse hängen auf der einen Seite innig zusammen mit der Entwickelung der äußeren christlich-kirchlichen Welt und mit alledem wiederum, was mit den Einrichtungen dieser christlich-kirchlichen Welt zusammenhängt. Auf der andern Seite hängen sie mit der ganzen geschichtlichen Entwickelung des Abendlandes innig zusammen. Bedenken wir einmal, daß der heutige Mensch es im Grunde außerordentlich schwer hat, sich mit seinen Empfindungen und Gedanken hineinzuversetzen in die Zeit, aus der, sagen wir, dieses Bild, das man so oftmals die «Disputa» genannt hat, herausgewachsen ist. Und noch schwieriger ist es für den heutigen Menschen, sich hineinzuversetzen in noch frühere Jahrhunderte, auch in die Jahrhunderte, in denen das Christentum schon gewaltet hat. Ich habe es ja oftmals erwähnt, man hat heute die Vorstellung: Ach, die Menschen sind immer so und so gewesen, wie sie heute sind. - Das ist aber durchaus nicht der Fall; insbesondere mit Bezug auf das Seelenleben sind die Menschen nicht so gewesen. Und als vor nahezu zwei Jahrtausenden das Mysterium von Golgatha sich hereingestellt hat in die Menschheitsentwickelung, da war neben dem, was dieses Mysterium von Golgatha für die Breite der sozialen Menschheitsentwickelung geworden ist, auch das Mysterium von Golgatha etwas ganz anderes, als es heute für die Auffassung der Menschen sein kann. Man stellt sich doch viel, viel zu schwach vor, was es bedeutet hat, daß ja ungefähr um die Zeit, in der dieses Bild entstanden ist, hereingebrochen ist über die Menschheit erstens die Entdeckung Amerikas am Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts; zweitens die ganz andere soziale Verfassung der Menschen, die durch die Erfindung der Buchdruckerkunst gekommen ist; endlich das, was mit dem Kopernikanismus, mit dem Keplerismus in der neueren Naturwissenschaft entstanden ist.

Sehen Sie sich dieses Bild an. Ich sagte, heute würde es, wenn ein Maler es malen würde, nicht mehr in demselben Sinne Wahrheit sein wie dazumal, könnte es nicht sein; denn man würde heute nicht die Seelen finden, denen dieses Bild in demselben Sinne wie dazumal, als es gemalt worden ist, gegenständlich wäre, Seelen, welche eine solche Vorstellung von der Erde haben, die bedingt ist dadurch, daß Amerika noch nicht entdeckt ist. Seelen, die noch in aufrichtiger Gläubigkeit zu den Wolken aufschauen, um über den Wolken das, was wir heute in der geistigen Welt vorzustellen haben, sich gewissermaßen körperlich-räumlich über den Wolken wirklich vorzustellen. Solche Seelen werden sich heute nicht mehr finden, auch nicht unter den naivsten Menschen. Aber wir stellen uns die Seelen der damaligen Zeit falsch vor, wenn wir nicht glauben, daß der Inhalt dieses Bildes etwas war, was diesen Seelen unbedingt gegenständlich war. Denken Sie doch nur einmal: der Inhalt dieses Bildes, was ist er denn? — Wir können ja heute von unserem geisteswissenschaftlichen Standpunkt aus einen Namen finden für das, was der Inhalt dieses Bildes ist; uns ist geläufig, von Imaginationen zu reden als der ersten Stufe der Schauungen nach der höheren Welt hinauf. Wenn wir sagen, die Menschheit bis zu diesem 16. Jahrhundert hinein hatte von der Welt, von der großen Raumeswelt im Zusammenhang mit der irdischen Welt eine Vorstellung, die in Imaginationen aufging, dann sagt man etwas Richtiges. Imaginationen waren dazumal noch etwas Lebendiges; und Raffael malte die lebendigen Imaginationen, die in den Seelen vorhanden waren. Weltanschauung, Weltbild waren dazumal noch etwas Imaginatives.

Diese Imaginationen wurden vertrieben durch die kaustische Kraft des Kopernikanismus, der Entdeckung Amerikas, der Buchdruckerkunst. Die Menschheit stellte erst von dieser Zeit an das äußerlich-gegenständliche Vorstellen des gesamten Weltengebäudes an die Stelle der Imagination, an die Stelle dessen, was wir die imaginative Erkenntnis, das imaginative Schauen nennen, so daß ja - während der gegenwärtige Mensch sich also vorstellt: da draußen ist die Sonne, da kreisen die Planeten herum und so weiter — die Leute das gar nicht hatten; wenn sie über etwas Ähnliches reden wollten, so redeten sie über Imaginationen. Und Abbild solcher Imaginationen ist dieses Bild. Die Jahrhunderte, in denen sich das imaginative Anschauen der Menschheit so allmählich herausgebildet hat, daß es dann mit solchen Bildern wie diesen Raffaelischen einen gewissen Abschluß im 16. Jahrhundert gefunden hat, diese Jahrhunderte sind also das 16., 15., 14., 13., 12., 11., 10. Jahrhundert, bis ins 9. Jahrhundert zurück, aber auch nicht weiter. Wenn wir weiter zurückgehen wollen, so bekommen wir keine richtigen Vorstellungen mehr, wenn wir uns selbst die imaginative Art, wie der Mensch in den genannten Jahrhunderten empfand, wenn wir uns diese — die wir ohnedies schon schwer genug heute vor die Seele rufen können - vorstellen.

Wenn wir das, was durch das Christentum in den Jahrhunderten vor dem 9. geworden ist, vorstellen wollen, dann müssen wir uns die christlichen Vorstellungen viel spiritueller vorstellen, als man das geneigt ist, gewöhnlich zu tun. Augustinus hat aus den christlichen Vorstellungen nur das herausgenommen, was er brauchen konnte. Aber wenn man Augustinus heute liest, bekommt man ja ein Gefühl davon, was anderes noch in den Seelen lebte als Weltbild und als Bild von Zusammenhängen der Welt mit den Menschen als später dann und heute. Und besonders bedeutsame Vorstellungen bekommen Sie, wenn Sie Scotus Eriugena lesen, der zur Zeit Karls des Kahlen gelehrt hat. Man möchte sagen: In diesen älteren Jahrhunderten vor dem 9. durchsetzten das christliche Denken bei denen, die sich überhaupt zum Denken erhoben, in diesen Jahrhunderten durchsetzten das christliche Denken hochspirituelle Vorstellungen. Man möchte sagen: Wenn die Menschen sich ein Weltbild machten in diesen älteren Jahrhunderten, dann nahmen sie in dieses Weltbild noch recht wenig von dem hinein, was die unmittelbar sinnliche Erfahrung gab, sie nahmen aber in dieses Weltbild um so mehr von dem hinein, was nicht die sinnliche Erfahrung gab, sondern was herausgenommen war aus dem alten hellseherischen Erschauen der Welt. Und wenn wir in die ersten Jahrhunderte nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha zurückgehen und die christlichen Vorstellungen verfolgen, dann finden wir, daß diese Vorstellungen solche sind, daß man eher sagen kann: Die Leute interessierte damals der himmlische Christus, der Christus, wie er in den geistigen Welten war; und was er geworden war auf Erden herunten, das betrachteten sie mehr so wie ein Anhängsel. Den Christus inmitten geistiger Wesenheit zu suchen, ihn zu denken im Zusammenhange mit dem Übersinnlich-Spirituellen, das war das wesentliche Bedürfnis; und das war aus der alten spirituellen — wenn auch atavistisch-spirituellen — Weltanschauung heraus. Diese Weltanschauung, die erfüllte ja die alte Kultur bis herunter in das dritte nachatlantische Zeitalter. Da dachte man die Erde wirklich als eine Art von Anhängsel zum Geistigen.

Nun muß man sich schon bekanntmachen mit einer Vorstellung, die ganz wesentlich ist, wenn man verstehen, wenn man begreifen will, wie die Menschheit sich eigentlich bis in unsere Tage entwickelt hat. Man muß sich bekanntmachen mit der Vorstellung, daß die europäische Menschheit zur Entfaltung ihrer Kultur die Zurückdrängung der spirituellen Vorstellungen notwendig hatte. Darüber darf man nicht mit Sympathie und nicht mit Antipathie urteilen; darüber darf man überhaupt nicht mit kritischem Geist urteilen, sondern man muß die Tatsachen einfach wie sie sind hinstellen; es war einfach das Schicksal, das Karma Europas, um zu der Kultur zu kommen, zu der es eben kommen mußte. Es war das Schicksal Europas, die spirituellen Vorstellungen zurückzudrängen, zurückzustauen gewissermaßen.

Und so kam es denn, daß sich vom 9. Jahrhundert an immer klarer und bedeutungsvoller zeigte: Europa braucht ein Christentum, welches die spirituellen Vorstellungen zurückdrängt. Und ein Ergebnis dieser Notwendigkeit ist die Kirchentrennung in die griechisch-orientalische und in die römisch-katholische Kirche. Damals trennt sich der Osten von dem Westen. Das ist etwas höchst Bedeutsames. Der Westen hat das Schicksal, die spirituellen Impulse nach dem Osten hin zurückzustauen. Da verbleiben sie. Und man versteht wirklich nicht, was im menschheitlichen Werden ist, wenn man nicht eben sich klar ist, daß diese an Asien und an Rußland angeschlossene europäische Halbinsel - Rußland rechne ich Jetzt zu Asien - nötig hatte, vom 8.,9. Jahrhundert ab die spirituellen Impulse nach dem Osten zurückzustauen. Die haben sich da zusammengestaut, entwickelten sich abseits vom westeuropäischen und mitteleuropäischen Leben, entwickelten sich in das heutige Rußland hinein.

Das ist sehr bedeutsam. Man halte das nur einmal ordentlich fest. Man ist heute gewöhnt, die Dinge durchaus nicht mehr im Zusammenhange betrachten zu wollen. Und so kommt einem ein solches Ereignis wie die russische Revolution vor wie etwas, was vor ein paar Monaten entstanden ist — was weiß ich, aus welchen Gründen heraus sich der eine oder andere das vorstellt -, während in Wahrheit das vorliegt, daß im Hintergrund von alledem eben das steht, daß ein gewisses, nach und nach im Laufe der Jahrhunderte in diesem Osten unsichtbar und ungreifbar gewordenes spirituelles Leben zurückgeschoben war, sich gestaut hat und jetzt in einer noch ganz undefinierbaren, chaotischen Weise so arbeitet, daß die Menschen, die in dem, was da im Osten vorgeht, drinnenstehen, wirklich so wenig in dem wirklich drinnen leben, wie die Menschen, die in der See schwimmen, in sich - wenn sie nicht gerade am Ertrinken sind — das Meerwasser haben; das Meerwasser haben sie außer sich. Und so ist auch das, was da an spirituellen Impulsen sich an die Oberfläche arbeitet im Osten, im Geistigen noch vorhanden. Die Menschen schwimmen darinnen und haben nicht viel Ahnung von dem, was da an die Oberfläche drängt und vom 9. Jahrhundert ab nach dem Osten zurückgeschoben worden ist, damit es dort gewissermaßen aufbewahrt werde, um in späteren Zeiten eine Entwickelung durchzumachen. Den Menschen, die im Osten entstanden, die im Osten allmählich sich herausbildeten aus der Völkerwanderung und aus sonstigen Verhältnissen, denen wurde in die Seelen hineingeschoben an spirituellen Impulsen, was zunächst der Westen und der Süden Europas und Mitteleuropas nicht gebrauchen konnten.

Der Westen behält sich etwas Merkwürdiges zurück. Der Osten, ohne daß er es weiß — die meisten wirklich wichtigen Dinge verlaufen ja für die Menschen im Unterbewußten -, der Osten, ohne daß er es wirklich weiß, blieb streng stehen auf der Grundlage des Evangeliensatzes: «Mein Reich ist nicht von dieser Welt». Daher schließt sich im Osten immer noch dasjenige, was physischer Plan ist, streng nach der spirituellen Welt, nach oben hin an. Der Westen war darauf angewiesen, geradezu umzukehren den Satz «Mein Reich ist nicht von dieser Welt» und so recht zu machen das Reich Christi als ein Reich von dieser Welt. Und dann sehen wir, daß Europa das Schicksal hat, von Rom aus das Reich Christi äußerlich wie ein Imperium zu konstituieren auf dem äußeren physischen Plan. Man möchte sagen: Von Rom aus wurde seit dem 9. Jahrhundert das Gesetz aufgestellt: Bruch mit dem alten Satze «Mein Reich ist nicht von dieser Welt», dafür aber gerade ein weltliches Reich zu konstituieren, welches das Reich des Christus Jesus auf Erden, auf dem physischen Plane sein sollte.

Der römische Papst wurde allmählich der, der da sagte: Mein Reich ist das Reich des Christus; aber dieses Reich Christi ist von dieser Welt; und wir haben es so zu konstituieren, daß es von dieser Welt ist, das Reich Christi. Aber es blieb ein Bewußtsein vorhanden, daß eben dieses Reich das Reich Christi ist, daß dieses Reich dasjenige Reich ist, das nicht aufgebaut sein soll auf die bloßen Grundsätze des natürlichen, des äußeren natürlichen Daseins. Man war sich dessen bewußt: Wenn man in die Natur hinaussieht, wenn man alles das sieht, was durch die Sonne und was durch die Morgen- und Abendröte ist, was durch die Sterne ist, dann hat man nicht bloß das vor sich, was Augen sehen, was Ohren hören, was Hände greifen können, sondern dann hat man in der Weite des unendlichen Raumes zu gleicher Zeit das vor sich, was das spirituelle Reich ist. Und all das, was hier in der sichtbaren Welt ist, ist gewissermaßen der letzte Ausfluß, der letzte Golf der spirituellen Welt. Und diese sichtbare Welt ist nur ein Ganzes, wenn man sich dessen voll bewußt ist, daß sie der Ausfluß ist einer spirituellen Welt. Diese spirituelle Welt ist konkret; die Menschen haben nur das Gesicht verloren für diese spirituelle Welt. Den Menschen ist sie verborgen; aber sie ist eine Realität, sie ist eine Wirklichkeit. Und wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes tritt, und er ist dafür besonders begnadet, so tritt er ein in die spirituelle Welt. Viel lebendiger, als man geneigt sein kann, sich das heute vorzustellen, waren daher diese Menschen zu denken. Wenn die Toten, namentlich die begnadeten Toten durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen waren, dann traten sie ein in eine Welt, die man sich gegenwärtig vorstellen muß — durchdringend die Wolken, durchdringend die Sterne, durchdringend die Planetenbahnen. Es war also etwas Konkretes, daß die Totenseelen hier im Bild die obere Gruppe bilden. Und die Totenseelen hatten das konkrete Mysterium, das konkrete Geheimnis der Dreifaltigkeit in ihrer Mitte, dieses konkrete Geheimnis, das sich zusammensetzt aus dem Wesenhaften der Vergangenheit — Gottvater; aus dem Wesenhaften der Gegenwart - dem Christus Jesus; aus dem Wesenhaften der Zukunft - dem Heiligen Geiste.

Was sich aber da auseinanderlegt in die Realität der Zeit, davon muß es, wenn die gegenwärtige Welt, die sinnenfällige Welt nicht eine bloße Illusion sein soll und die Menschen innerhalb dieser sinnlichen Welt wie die Tiere leben wollen, davon muß es in dieser sinnlichen Welt auf dem physischen Plan Zeichen geben für das, was unsichtbar in der geistigen Welt über den Wolken schwebt und wohnt. Die Nachgeborenen müssen lebendige Zeichen haben von dem, wovon die Vorgeborenen, die nun schon Postmortem-Seelen sind, die unmittelbare Anschauung haben.

Auf dem Altar steht der Kelch mit dem Sanktissimum, mit der Hostie. Diese Hostie ist nicht bloß äußere Materie für die Menschen, die da links und rechts unten herumstehen, sondern diese Hostie ist rings umflossen von ihrer Aura. Und mit der Aura dieser Hostie wirken die Kräfte, die von der Dreieinigkeit herunterkommen. Solche Vorstellungen, wie sie in den Köpfen der Kirchenväter, der Bischöfe, der Päpste über das auf dem Altar befindliche Sanktissimum leben, hat die heutige Menschheit gar nicht mehr. Die sind im Laufe der Zeit vergangen. Und der Moment ist hier festgehalten im Bilde, in dem es diesen Leuten am Altare unten aufgeht: Da ist ein Mysterium, das auf dem Altar steht; da wird die Hostie von etwas umschwebt. Und dieses Etwas, das sehen die Verstorbenen-Seelen, namentlich die begnadeten: David, Abraham, Adam und Moses, Petrus, Paulus — das sehen die Verstorbenen so, wie die hier auf dem physischen Plan befindlichen Seelen die Gegenstände der sinnlichen Welt sehen.

Wenn wir uns dieses Untere (197) ansehen, mit dem Sanktissimum in der Mitte, dann haben wir in dem, was da unten, gewissermaßen in der untersten Etage des Bildes steht, das vor uns, von dem solch ein Mensch wie Papst Julius II. etwa gesagt hat: Das will ich in so großer Herrlichkeit, als es nur möglich ist, auf der Erde von Rom aus herstellen, ein solches Reich, ein solches Imperium begründen - nicht einen Staat, sondern ein Imperium -, ein solches Reich begründen, daß in diesem Reiche, in diesem Imperium Dinge geschehen, die umflossen sind von solchen Auren, daß die Vergangenheit mit ihren Impulsen in diesen Auren lebt. Ein Reich also, das von dieser Welt ist, aber das, indem es von dieser Welt ist, Zeichen ist, Signum ist für das, was in den spirituellen Welten lebt.

Vorstellungen solcher Art wird Julius II. in Bramante zuerst und dann in dem jugendlichen Raffael entzündet haben. Dadurch ist es dazu gekommen, daß der junge Raffael dieses Bild komponieren konnte. Gewissermaßen in seinem Arbeitszimmer wollte Julius II. dieses Bild haben, um es immer vor sich zu haben wie eine heilige Devise, daß von Rom aus das Imperium begründet werden solle, in dem die wichtigsten Dinge die Mysterien sind. Aber dieses Reich sollte von dieser Welt sein, von dieser Welt mit dem spirituellen Einschluß.

Nur wenn man alle diese Empfindungen, von denen wir jetzt gesprochen haben, auf seine Seele wirken läßt, hat man einen Eindruck von diesem Bilde, wenn man sich sagt: Die spirituelle Welt war nach dem Osten seit dem 9. Jahrhundert, ich möchte sagen so zurückgeschoben, wie hier die Wolken nach aufwärts geschoben sind, und wartete nun dort, bis ihre Zeit gekommen war.

Dagegen bereitete sich vor - einstweilen im Westen — das fünfte nachatlantische Zeitalter, dieses fünfte nachatlantische Zeitalter, in dem wir ja immer noch leben, und in dem die Menschheit lange leben wird, und das ganz unter der Signatur steht: Mein Reich ist von dieser Welt. Und immer mehr und mehr wird das Reich dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters von dieser Welt sein. Aber in dieses Reich, das von dieser Welt ist, werden solche Dinge hineingestellt, fast am Anfange, am Beginne dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters unter dem Einflusse der alten Leute Bramante und Julius II., von dem jugendlichen Raffael. Die wichtigsten Dinge geschehen ja in der geschichtlichen Entwickelung unbewußt. Und aus unbewußten, aber weisheitsvollen Untergründen heraus hat sich Julius II. den Raffael geholt. Wir wissen, daß die Menschheit im Laufe der Jahrtausende immer jünger geworden ist; wir wissen, daß sie im Anfange des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters das Alter der Achtundzwanzigjährigkeit erreicht hat, jetzt «27 Jahre alt» ist. Gewiß, Bramante und Julius II. waren alte Leute; aber sie waren es auch nicht, die unmittelbar in die Welt hineingestellt haben, was nur der jugendliche Raffael mit seinem Leib hineinstellen konnte, der eben ein jugendlicher Leib war und der die Kraft gerade des Achtundzwanzigjährigen hatte, als er so etwas malte. Das sind bedeutsame spirituelle Hintergründe in der Menschheitsentwickelung.

Und jetzt vergegenwärtigen wir uns, wie Raffael an dem Ihnen eben charakterisierten Gedanken in Rom malte, malte gewissermaßen den Protest des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitalters gegen das fünfte nachatlantische Zeitalter. Es war ja nicht so; aber denken wir uns hypothetisch, es wäre in Raffaels Seele das Folgende angeregt worden: Vor Raffaels Seele wäre gestellt worden - in ihrem Unbewußten lebte es, wir können dieses Unbewußte aber hypothetisch vor uns hinstellen -, nehmen wir an, in Raffaels Seele lebte das Wissen dessen, was als fünftes nachatlantisches Zeitalter kommen sollte. Kommen sollte die entgötterte, entgeistigte Welt des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters, in dem die Menschheit sich den kahlen, öden, eisigen Weltenraum denkt, durchsetzt, durchlaufen von Sonne und Planeten, geistlos den öden Weltenraum vorstellt, geistlos sich die Erde selbst vorstellt und versucht, durch geistlose Naturgesetze sich ein ganzes Weltenwerden zu konstruieren. Nehmen wir an, das wäre vor Raffaels Seele hingestellt worden: die Realität der Geistlosigkeit des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters. Und diese Seele Raffaels hätte dagegen die Impression gestellt: So darf es nicht sein; ich will hineinwerfen in dieses geistlose Zeitalter, das sich den eisigen Weltenraum mit dem geistlosen Weltennebel im Sinne der Kant-Laplaceschen Theorie hinstellt, die Imagination des lebendigen spirituellen Daseins. Ich will erfüllen, soviel ich kann, in der Vorstellung dieses öde naturhistorische Dasein mit den Imaginationen, die sich ergeben aus dem alten hellseherischen Erfassen der Welt. - Nehmen Sie an, so hätte es in der Seele Raffaels ausgesehen. Es hat so ausgesehen in dem Unterbewußten seiner Seele; es hat selbst so ausgesehen in der Seele Julius II.

Unser Zeitalter hat wahrhaftig nicht nötig, die großen Geister wie Julius II. oder selbst die Borgias so zu verachten, wie es die Geschichtslegende tut; denn die Geschichte wird über unsere Zeitgenossen, über die Größten unseres Zeitalters ganz andere Urteile noch zu fällen haben als wir über die Borgias oder Julius II. oder über ähnliche Persönlichkeiten der Vorzeit. Die Menschen der Gegenwart haben nur nicht die Distanzen dazu.

So war Raffael am Beginne des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters geboren, man möchte sagen, so recht geboren als ein Kind des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters. Er ist ja wirklich schon aus diesem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalter herausgeboren, aber wie die lebendig gegen dieses Zeitalter protestierende Seele, die in Schönheit in dieses Zeitalter hineinstellen will, was dieses Zeitalter nicht mehr als Wahrheit erleben will; die sinnenfällige Spiritualität in die spiritualitätslose Sinnenfälligkeit hineintragen will; das herübertragen will in das fünfte nachatlantische Zeitalter, was alte Zeitalter aus spirituellem Schauen heraus gewonnen haben. Was spirituell geschaut werden konnte, in sinnenfälligen Bildern übertragen in das Reich dieser Welt, ein zweites Reich in diese Welt, in das, was sinnenfällig, aber in der Sinnenfälligkeit voller Zeichen des Übersinnlichen ist, hineinstellen - das war ungefähr Raffaels Absicht. Und die Wahrheit davon ist dieses Bild, ein durch und durch wahres Bild, weil es aus dem lebendigen Empfinden der damaligen Zeit heraus entsprungen ist.