Soul Economy

Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education

GA 303

23 December 1921, Stuttgart

I. The Three Phases of the Anthroposophic Movement

Before the conference began, Rudolf Steiner addressed the participants gathered in the White Hall of the Goetheanum:

“Ladies and Gentlemen, before beginning this lecture course, allow me to bring up an administrative matter. Originally, this course was meant for a smaller group, but it has drawn such a response that it has become clear that we cannot gather in this tightly-packed hall. It would be impossible, and you would soon realize this if you were to attend both the lectures and the translations. Consequently, I have decided to present the lectures twice—the first each day at ten A.M. and again at eleven, for those who wish to hear it translated into English. For technical reasons this is the only way to proceed. Therefore, I will begin the earlier lectures exactly at ten and second at eleven o’clock. I will ask those who came from England, Holland, and Scandinavia to attend the later lectures and everyone else to attend the first.”

First of all I would like to express my great joy at meeting so many of you here in this hall. Anyone whose life is filled with enthusiasm for the movement centered here at the Goetheanum is bound to experience happiness and a deep inner satisfaction at witnessing the intense interest for our theme, which your visit has shown. I would therefore like to begin this introductory lecture by welcoming you all most warmly. And I wish to extend a special welcome to Mrs. Mackenzie, whose initiative and efforts have brought about this course. On behalf of the anthroposophic movement, I owe her a particular debt of gratitude.

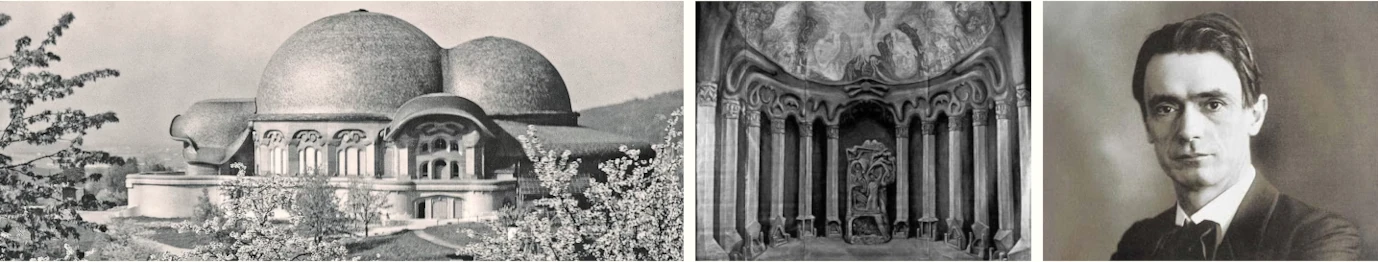

I would like to add that it is not just a single person who is greeting you here, but that, above all, it is this building, the Goetheanum itself, that receives you. I can fully understand if some of you feel critical of certain features of this building as a work of art. Any undertaking that appears in the world in this way must be open to judgment, and any criticism made in good faith is appreciated—certainly by me. But, whatever your reactions may be to this building, it is the Goetheanum itself that welcomes you. Through just its forms and artistic composition, you can see that the aim here was not to erect a building for specific purposes, such as education, for example. The underlying spirit and style of this building shows that it was conceived and erected from the spirit of our time, to serve a movement and destined to play its part in our present civilization. And because education represents an integral part of human civilization, it is proper for it to be nurtured here at this center.

The close relationship between anthroposophic activities and problems of education will occupy us in greater detail within the next few days. Today, however, as part of these introductory remarks, I would like to talk about something that really is a part of any established movement. In a sense, you have come here to familiarize yourselves with the various activities centered here at the Goetheanum, and in greeting you most warmly as guests, I feel it right to begin by introducing you to our movement.

The aims of this anthroposophic movement, which has been in existence now for some twenty years, are only gradually beginning to manifest. It is only lately that this movement has been viewed by the world at large in ways that are consistent with its original aims. Nevertheless, this movement has gone through various phases, and a description of these may provide the most proper introduction.

Initially, the small circle of its adherents saw anthroposophy as a movement representing a very narrow religious perspective. This movement tended to attract people who were not especially interested in its scientific background and were not inclined to explore its artistic possibilities. Nor were they aware of how its practical activities might affect society as a whole. The first members were mainly those dissatisfied with traditional religious practice. They were the sort of people whose deepest human longings prompted them to search for answers to the problems inherent in the human soul and spirit—problems that could not be answered for them by existing religious movements.

For me it often was quite astonishing to see that what I had to say about the fundamentals of anthroposophy was not at all understood by members who, nevertheless, supported the movement with deep sympathy and great devotion. When matters of a more scientific nature was discussed, these initial members extracted what spoke to their hearts and appealed to their immediate feelings and sentiments. And I can truly say that it was the most peaceful time within the anthroposophic movement, though this was certainly not what I was looking for. Because of this situation, during its first phase the anthroposophic movement was able to join another movement (though only outwardly and mainly from an administrative perspective), which you might know as the Theosophical Society.

Unless they can discern the vital and fundamental differences, those who search with a simple heart for knowledge of the eternal in human nature will find either movement equally satisfactory. The Theosophical Society is concerned primarily with a theoretical knowledge that embraces cosmology, philosophy, and religion and uses the spoken and printed word as its means of communication. Those who are satisfied with their lives in general, but wish to explore the spirit beyond what traditional doctrines offer, might find either movement equally satisfying. But (and only a few members noticed this) once it became obvious that, in terms of cosmology, philosophy, and religion, anthroposophic goals were never intended to be merely theoretical but to enter social life in a direct and practical way according to the demands of the spirit of our times—only then did it gradually become obvious that our movement could no longer work within the Theosophical Society. For in our time (and this will become clear in the following lectures), any movement that limits itself to theories of cosmology, philosophy, and religion is bound to degenerate into intolerable dogmatism. It was the futility of dogmatic arguments that finally caused the separation of the two movements.

It is obvious that no one who is sensible and understands western culture could seriously consider what became the crux of these dogmatic quarrels that led to this split. These quarrels were sparked by claims that an Indian boy was the reincarnation of Christ. Since such a claim was completely baseless, it was unacceptable.

To waste energy and strength on theoretical arguments is not the way of anthroposophy, which aims to enter life directly. When it became necessary to work in the artistic, social, scientific, and—above all—in the educational realm, the true aims of anthroposophy made it necessary to separate from the Theosophical Society. Of course, this did not happen all at once; essentially, all that happened in the anthroposophic movement after 1912 demonstrated that this movement had to fight for its independence in the world, if it was going to penetrate ordinary life.

In 1907, during a Theosophical Society congress in Munich, I realized for the first time that it would be impossible for me to work with this movement. Along with my friends from the German section of the Theosophical Society, I had been given the task of arranging the program for this congress. Apart from the usual items, we included a performance of a mystery play by Edouard Schuré (1841–1929), The Sacred Drama of Eleusis. We decided to create a transition from the movement’s religious theories to a broader view that would encourage artistic activity. From our anthroposophic perspective, we viewed the performance as an artistic endeavor. But there were people in the movement who tried to satisfy their sometimes egotistical religious feelings by merely looking for a theoretical interpretation. They would ask, What is the meaning of this individual in the drama? What does that person mean? Such people would not be happy unless they could reduce the play to theoretical terms.

Any movement that cannot embrace life fully because of a lopsided attitude will certainly become sectarian. Spiritual science, on the other hand, is not the least inclined toward sectarianism, because it naturally tends to bring ideals down to earth and enter life in practical ways.

These attempts to free the anthroposophic movement from sectarianism by entering the artistic sphere represent the second phase of its history. Gradually, as membership increased, a need arose for the thought of philosophy, cosmology, and religion to be expressed artistically, and this in turn prompted me to write my mystery plays. And these must not be interpreted theoretically or abstractly, because they are intended to be experienced directly on the stage. To bring this about, my plays were performed in ordinary, rented theaters in Munich, from 1910 to 1913. And this led to an impulse to build a center for the anthroposophic movement. The changing situation made it clear that Munich was inappropriate for such a building, and so we were led to Dornach hill, where the Goetheanum was built as the right and proper place for the anthroposophic movement.

These new activities showed that, in keeping with its true spirit, the anthroposophic movement is always prepared to enter every branch of human life. Imagine that a different movement of a more theoretical religious character had decided to build a center; what would have happened? First, its members would collect money from sympathizers (a necessary step, unfortunately). Then they would choose an architect to design the building, perhaps in an antique or renaissance style or in a gothic or baroque or some other traditional style.

However, when the anthroposophic movement was in the happy position of being able to build its own home, such a procedure would have been totally unacceptable to me. Anything that forms an organic living whole cannot be assembled from heterogeneous parts. What relationship could any words, spoken in the spirit of anthroposophy, have had with the forms around a listener in a baroque, antique, or renaissance building? A movement that expresses only theories can present only abstractions. A living movement, on the other hand, must work into every area of life through its own characteristic impulses. Therefore, the urge to express life, soul, and spirit in practical activity (which is characteristic of anthroposophy) demanded that the surrounding architecture—the glowing colors of the wall paintings and the pillars we see—should speak the same language that is spoken theoretically in ideas and abstract thoughts. All of the movements that existed in the world previously were equally comprehensive; ancient architecture was certainly not isolated from its culture, but grew from the theoretical and practical activities of the time. The same can be said of the renaissance—certainly of the gothic, but also of the baroque.

To avoid a sectarian or theoretical ideology, anthroposophy had to find its own architectural and artistic styles. As mentioned before, one may find this style unsatisfactory or even paradoxical, but the fact is, according to its real nature, anthroposophy simply had to create its own physical enclosure. Let me make a comparison that may appear trivial but may, nevertheless, clarify these thoughts. Think of a walnut and its kernel. It is obvious that both nut and shell were created by the same forces, since together they make a whole. If anthroposophy had been housed in an incongruous building, it would be as if a walnut kernel had been found in the shell of a different plant. Nature produces nut and shell, and they both speak the same language. Similarly, neither symbolism nor allegory was needed here; rather, it was necessary that anthroposophic impulses flow directly into artistic creativity. If thoughts are to be expressed in this building, they must have a suitable shell, from artistic and architectural points of view. This was not easy to do, however, because the sectarian tendency is strong today, even among those looking for a broadening of religious ideals. But anthroposophy must not be influenced by people’s sympathies or antipathies. It must remain true to its own principles, which are closely linked to the needs and yearnings of our times, as will be shown in the next few days.

And so anthroposophy entered the practical domain—as far as this was possible in those days. At the time, I surprised some members by saying, “Anthroposophy wants to enter all walks of life. Although conditions do not allow this today, I would love to open banks that operate according to anthroposophic principles.” This may sound strange, but it was meant to show that anthroposophy is in its right element only when it can fertilize every aspect of life. It must never be seen merely as a philosophical and religious movement.

We now come to the catastrophic and chaotic time of the World War, which produced its own particular needs. In September 1913, we laid the foundation stone of this building. In 1914, when war broke out, we were building the foundation of the Goetheanum. Here I want to say only that, at a time when Europe was torn asunder by opposing nationalistic aspirations, here in Dornach we successfully maintained a place where people from all nations could meet and work together in peace, united by a common spirit. This was a source of deep inner satisfaction. Those war years could be considered as the second phase in the development of our movement.

Despite efforts to continue anthroposophic work during the war, the outer activities of the anthroposophic movement were mostly paralyzed. But one could experience how peoples everywhere gradually came to feel an inner need for spiritual sustenance, which, in my opinion, anthroposophy was able to offer. After 1918, when the war had ended, at least outwardly, there was an enormous, growing interest in spiritual renewal, such as anthroposophy wished to provide. Between autumn 1918 and spring 1919, numerous friends—many from Stuttgart—came to see me in Dornach. They were deeply concerned about the social conditions of the time, and they wanted the anthroposophic movement to take an active role in trying to come to terms with the social and economic upheavals. This led to the third phase of our movement.

It happened that Southern Germany—Württemberg in particular—was open to such anthroposophic activities, and one had to work wherever this was possible. These activities, however, were colored a little by the problems of that particular region, problems caused by the prevailing social chaos. An indescribable misery had spread over the whole of Central Europe at the time. Yet, seen in a broader context, the suffering caused by material needs was small compared to what was happening in the soul realm of the population. One could feel that humanity had to face the most fundamental questions of human existence. Questions once raised by Rousseau, which led to visible consequences in the French Revolution, did not touch the most basic human yearnings and needs as did the questions presented in 1919, within the very realms where we wished to work.

In this context, awareness of a specific social need began to grow in the hearts of my friends. They realized that perhaps the only way to work effectively toward a better future would be to direct our efforts toward the youth and their education. Our friend Emil Molt (who at the time was running the Waldorf- Astoria Cigarette Factory in Stuttgart) offered his services for such an effort by establishing the Waldorf school for his workers’ children, and I was asked to help direct the school. People were questioning everything related to the organization of society as it had developed over the past centuries from its tribal and ethnic elements. This prompted me to present a short proclamation concerning the threefold social order to the German people and to the civilized world in general, and also to publish my book Towards Social Renewal.

Many other activities connected with the social question also occurred, at first in South Germany, which resulted from this general situation and prevailing mood. It was essential then, though immensely difficult, to touch the most fundamental aspirations of the human soul. Despite their physical and mental agony, people were called upon to search, quite abstractly, for great and sublime truths; but because of the general upheaval they were unable to do so. Many who heard my addresses said to me later, “All this may be correct and even beautiful, but it concerns the future of humanity. We have faced death often during the last years and are no longer concerned about the future; we must live from day to day. Why should we be more interested in the future now than when we had to face the guns every day?” Such comments characterize the prevaling apathy of that time toward the most important and fundamental questions of human development.

Before the war, one could observe all sorts of educational experiments in various special schools. It was out of the question, however, that we would establish yet another country boarding school or implement a certain brand of educational principles. We simply wished to heal social ills and serve the needs of humankind in general. You will learn more about the fundamentals of Waldorf education during the coming lectures. For now, I merely wish to point out that, as in every field, anthroposophy sees its task as becoming involved in the realities of a situation as it is given. It was not for us to open a boarding school somewhere in a beautiful stretch of open countryside, where we would be free to do as we pleased. We had to fit into specific, given conditions. We were asked to teach the children of a small town—that is, we had to open a school in a small town where even our highest aspirations had to be built entirely upon pragmatic and sound educational principles. We were not free to choose a particular locality nor select students according to ability or class; we accepted given conditions with the goal of basing our work on spiritual knowledge. In this way, as a natural consequence of anthroposophic striving, Waldorf education came into existence.

The Waldorf school in Stuttgart soon ceased to be what it was in the beginning—a school for the children of workers at the Waldorf-Astoria Cigarette Factory. It quickly attracted students from various social backgrounds, and today parents everywhere want to send their children. From the initial enrollment of 140 children, it has grown to more than 600, and more applications are coming in all the time. A few days ago, we laid the foundation stone for a very necessary extension to our school, and we hope that, despite all the difficulties one must face in this kind of work, we will soon be able to expand our school further.

I wish to emphasize, however, that the characteristic feature of this school is its educational principles, based on knowledge of the human being and its ability to adapt those principles to external, given realities. If one can choose students according to ability or social standing, or if one can choose a locality, it is relatively easy to accomplish imaginary, even real, educational reforms. But it is no easy task to establish and develop a school on educational principles closely connected with the most fundamental human impulses, while also being in touch with the practical demands of life.

Thus, during its third phase, our anthroposophic movement has spread into the social sphere, and this aspect will naturally occupy us in greater depth during the coming days. But you must realize that what has been happening in the Waldorf school until now represents only a beginning of endeavors to bring our fundamental goals right down into life’s practicalities.

Concerning other anthroposophic activities that developed later on, I would like to say that quite a number of scientifically trained people came together in their hope and belief that the anthroposophic movement could also fertilize the scientific branches of life. Medical doctors met here, because they were dissatisfied with the ways of natural science, which accept only external observation and experimentation. They were convinced that such a limited attitude could never lead to a full understanding of the human organism, whether in health or illness. Doctors came who were deeply concerned about the unnecessary limitations established by modern medical science, such as the deep chasm dividing medical practice into pathology and therapy.

These branches coexist today almost as separate sciences. In its search for knowledge, anthroposophy uses not just methods of outer experimentation—observation of external phenomena synthesized by the intellect—but, by viewing the human being as body, soul, and spirit, it also utilizes other means, which I will describe in coming days. Instead of dealing with abstract thoughts, spiritual science is in touch with the living spirit. And because of this, it was able to meet the aspirations of those urgently seeking to bring new life into medicine. As a result, I was asked to give two courses here in Dornach to university-trained medical specialists and practicing doctors, in order to outline the contribution spiritual science could make in the field of pathology and therapy. Both here in Dornach and in nearby Arlesheim, as well as in Stuttgart, institutes for medical therapy have sprung up, working with their own medicines and trying to utilize what spiritual science can offer to healing, in dealing with sickness and health. Specialists in other sciences have also come to look for new impulses arising from spiritual science; thus, courses were given in physics and astronomy. In this way, anthroposophic spirit knowledge was called upon to bring practical help to the various branches of science.

Characteristic of this third phase of the anthroposophic movement is the fact that gradually—despite a certain amount of remaining opposition—people have come to see that spiritual science, as practiced here, can meet every demand for an exact scientific basis of working and that, as represented here, it can work with equal discipline and in harmony with any other scientific enterprise. In time, people will appreciate more and more the potential that has been present during these past twenty years in the anthroposophic movement.

Yet another example shows how the most varied fields of human endeavor can be fructified through spiritual science, through the creation of a new art of movement we call eurythmy. It uses the human being as an instrument of expression, and it aims toward specific results. So we try to let anthroposophic life—not anthroposophic theories—flow into all sorts of activities—for example, the art of recitation and speech, about which you will hear more in the next few days.

This last phase with its educational, medical, and artistic impulses is the most characteristic one of the anthroposophic movement. Spiritual science has many supporters as well as many enemies—even bitter enemies. But now it has entered the very stage of activities for which it has been waiting. And so it was a satisfying experience during my stay in Kristiania [Oslo], from November twenty-third to December fourth this year to speak of anthroposophic life to educators and to government economists, as well as to Norwegian students and various other groups. All of these people were willing to accept not theories or religious sectarian ideas, but what waits to reveal itself directly from the spirit of our time in answer to the great needs of humanity.

So much for the three phases of the anthroposophic movement. As an introduction to our course I merely wanted to acquaint you with this movement and to mention its name to you, so to speak. Tomorrow, we will begin our actual theme. Nevertheless, I want you to know that it is the anthroposophic movement, with its deep educational interests, that gladly welcomes you all here to the Goetheanum.

Erster Vortrag

Vor Beginn des pädagogischen Kurses richtete Rudolf Steiner an die Teilnehmer, die im «weißen Saal» des ersten Goetheanum versammelt waren, folgende Worte:

«Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, gestatten Sie, bevor ich beginne mit meinen Auseinandersetzungen, eine administrative Sache vorzubringen. Der Kursus war ursprünglich nur für einen intimen Kreis veranlagt, und nun hat er einen so zahlreichen Besuch erfahren, daß ja vorauszusehen ist, daß wir den Kurs nicht in entsprechender Weise absolvieren können, wenn wir hier in diesem Saal so gedrängt sitzen. Das würde unmöglich sein; Sie würden das schon bemerken, wenn Sie eben da sein müßten während des Vortrags und während der Übersetzung. Deshalb muß ich mich dazu entschließen, den Kursus zweimal zu halten, und zwar das erstemal jeden Tag um 10 Uhr, und dann für diejenigen Herrschaften vor allen Dingen, welche an der Übersetzung teilnehmen wollen, weil das ja technisch sich nicht anders machen läßt, um 11 Uhr dann. Ich werde also den ersten Vortrag jeden Tag pünktlich um 10 Uhr beginnen, und die Wiederholung dann um 11 Uhr. Ich bitte, vielleicht die Sache so einzuteilen, daß alle die verehrten Anwesenden, welche aus England, Holland, Skandinavien da sind, eben an dem zweiten Vortrag teilnehmen, und die anderen an dem ersten.»

Das erste Wort, das ich ausspreche, soll ein Wort der herzlichen Freude und der innigen Befriedigung sein über Ihren Besuch, meine Damen und Herren. Derjenige, welcher für die Bewegung, welche von dem Goetheanum hier ihren Ausgangspunkt nehmen möchte, am intensivsten enthusiasmiert ist, der muß gegenüber einem Interesse, das sich in einer so außerordentlichen Weise durch Ihren Besuch zeigt, eben tiefst erfreut und innigst befriedigt sein. Und aus dieser Freude und dieser Befriedigung heraus gestatten Sie mir, daß ich Sie hier heute im Beginne dieses einleitenden Vortrages in der herzlichsten Weise begrüße.

Insbesondere darf ich Frau Professor Mackenzie begrüßen, deren Bemühungen es gelungen ist, diesen Kursus zu inaugurieren, und der ich deswegen im Namen der anthroposophischen Bewegung ganz besonderen Dank schulde. Aber Sie alle begrüße ich auf das herzlichste aus dem ganzen Geist und dem Sinn unserer Bewegung heraus. Und, meine Damen und Herren, es ist ja hier so, daß nicht nur eine einzelne Persönlichkeit Sie begrüßt, sondern daß Sie vor allen Dingen hier der Bau, das Goetheanum selber begrüßt.

Es ist mir durchaus begreiflich, daß der eine oder der andere von Ihnen an diesem Goetheanum als Bau, als Kunstwerk, manches auszusetzen haben wird. Allein, alles dasjenige, was in dieser Weise in die Welt tritt, unterliegt selbstverständlich der Kritik, und jeder Widerspruch, der aus guter Meinung heraus kommt, wird insbesondere mir selbst durchaus willkommen sein. Aber dennoch begrüßt Sie dieses Goetheanum, dessen Form und dessen künstlerische Ausgestaltung Sie ja darauf hinweisen wird, daß es sich hier nicht allein darum handelt, ein einzelnes Gebiet der menschlichen Lebenspraxis zu inaugurieren, auch nicht etwa in einseitiger Weise bloß das erzieherische Unterrichtsgebiet. Der ganze Geist dieses Baues und das Dasein dieses Baues kann Ihnen anzeigen, daß es sich hier um eine aus dem Geist unserer Zeit heraus gedachte und heraus gewollte Bewegung für unsere ganze Zivilisation handelt. Und insoferne Erziehung und Unterricht wesentliche Teile der menschlichen Zivilisation sind, müssen insbesondere auch Erziehung und Unterricht von hier aus ihre besondere Pflege finden.

Die intimen Beziehungen zwischen dem anthroposophischen Wollen und den Erziehungs- und Unterrichtsfragen werden uns ja in den nächsten Tagen in ausführlicher Weise vor die Seele treten können. Heute aber gestatten Sie mir, daß ich zu dem herzlichsten Gruße, den ich Ihnen darbringe, etwas hinzufüge, was gewissermaßen auf dem Boden einer ja auch gesellschaftlichen Bewegung sich in gewissem Sinne selbst versteht.

Sie sind gewissermaßen hierhergekommen, um sich zu informieren, wie es steht mit den Bewegungen, die vom Goetheanum in Dornach ausgehen. Indem ich Sie in herzlicher Weise in diesem Goetheanum als willkommene Gäste begrüße, fühle ich mich aber verpflichtet, wie das ja sonst auch im gesellschaftlichen Verkehre der Menschen durchaus in ähnlichem Falle Pflicht ist, Ihnen vor allen Dingen die Bewegung, die von hier aus ihren Ausgangspunkt findet, einmal vorzustellen.

Dasjenige, was mit dieser anthroposophischen Bewegung schon seit ihrem Anfang vor zwanzig Jahren gewollt worden ist, das kommt eigentlich erst jetzt langsam zur Offenbarung. Im Grunde genommen — Sie werden das aus den folgenden Vorträgen ersehen — war diese Bewegung von vorneherein als dasjenige gedacht, als was sie heute im zustimmenden Sinne, und vor allen Dingen auch im ablehnenden Sinne, von der Welt genommen wird. Heute erst beginnt man von dieser anthroposophischen Bewegung so zu sprechen, wie sie ursprünglich gedacht war. Allein diese anthroposophische Bewegung hat die verschiedensten Phasen durchgemacht, und an diesen Phasen werde ich Ihnen am leichtesten diese Bewegung zunächst einmal rein äußerlich vorstellen können.

Zunächst wurde die anthroposophische Bewegung von dem kleinen Kreise, der sich zu ihr bekannte, wie eine Art im engeren Sinne religiöser Weltanschauung genommen. Menschen, die sich wenig bekümmerten um wissenschaftliche Fundierung, die sich wenig bekümmerten um künstlerische Ausgestaltungen und um die Konsequenzen der anthroposophischen Lebenspraxis für das gesamte soziale Leben, solche Menschen kamen zunächst an diese anthroposophische Bewegung heran. Menschen, die vor allen Dingen sich unbefriedigt fühlten innerhalb der gegenwärtigen traditionell religiösen Bekenntnisse, Menschen, die dasjenige suchten, was aus den tiefsten menschlichen Sehnsuchten heraus kommt in bezug auf die großen Fragen der menschlichen Seele und des menschlichen Geistes, Menschen, die sich in bezug auf diese Fragen von den traditionellen Vorstellungen vorhandener Religionsbekenntnisse tief unbefriedigt fühlten, kamen an diese Bewegung heran, und sie nahmen zunächst diese Bewegung auf mit ihrem Gefühl, mit ihrer Empfindung.

Für mich selbst war es oftmals erstaunlich, zu sehen, wie dasjenige, was ich über Anthroposophie auszusprechen hatte, eigentlich in bezug auf seine Fundierung auch von den Anhängern durchaus nicht durchschaut worden ist, wie aber dieser anthroposophischen Bewegung aus schlichten und elementaren menschlichen Empfindungen Sympathie und Anhängerschaft entgegengebracht worden ist. Aus dem, was von Anfang an im Grunde genommen eine wissenschaftliche Orientierung hatte, hörten diese ersten Anhänger dasjenige heraus, was zu ihren Herzen sprach, was zu ihrem unmittelbaren Gefühle, zu ihrer Empfindung sprach. Und man kann sagen, es war dieses die ruhigste Zeit — obwohl Ruhe nach dieser Richtung nicht immer erwünscht ist —, es war dieses die ruhigste Zeit der anthroposophischen Bewegung.

Weil dies so war, konnte diese anthroposophische Bewegung in ihrer ersten Phase durchaus zunächst aufgenommen werden und mitgehen — rein äußerlich allerdings, in bezug auf das bloß administrative Mitgehen — mit derjenigen Bewegung, die Sie vielleicht kennen als die Bewegung der Theosophischen Gesellschaft.

Menschen, welche in der geschilderten Art aus ihrem schlichten Herzen heraus nach den Fragen des Ewigen in der menschlichen Natur suchen, sie finden zuletzt, wenn sie manches Wesentliche und Fundamentale eben übersehen, gleichmäßig ihre Befriedigung in der theosophischen Bewegung und in der anthroposophischen Bewegung. Allein die theosophische Bewegung war von vorneherein nach einer gewissen bloß theoretischen Seite hin orientiert. Die theosophische Bewegung will eine Lehre sein, wie sie sich in Worten ausspricht, welche eine Kosmologie, eine Philosophie und eine Religion umfaßt, und insofern man die Kosmologie, Philosophie und Religion durch Worte verkündigen kann, will sich die theosophische Bewegung ausleben. Menschen, die in bezug auf die übrigen Verhältnisse des Lebens eigentlich in ihrer Lebenslage zufrieden sind und nur etwas anderes über die Fragen des Ewigen hören wollen, als die traditionellen Religionsbekenntnisse liefern können, solche Menschen finden in gleicher Weise oftmals ihre Befriedigung in der einen und in der anderen Bewegung. Und erst als sich zeigte, trotzdem es damals wenig bemerkt worden ist, daß Anthroposophie etwas sein will, was nicht bloß theoretisch sich ergehen will über Kosmologie, Philosophie und Religion, sondern was gemäß den Forderungen des gegenwärtigen Zeitgeistes in die wirkliche Lebenspraxis auf allen Gebieten einzugreifen hat, da stellte sich allmählich durch innere Gründe die Unmöglichkeit heraus, daß anthroposophische Bewegung weiter zusammen wirke mit der theosophischen Bewegung. Denn heute - auch das wird sich uns in den weiteren Vorträgen zeigen — artet jede Art von Bewegung, die sich auf diese drei Gebiete, auf Kosmologie, auf Philosophie und Religion in einem mehr theoretischen Sinne beschränkt, es artet jede solche Bewegung in ein zuletzt unerträgliches Dogmengezänke aus. Und ein Dogmengezänke, das sich im Grunde genommen in Nichtigkeiten bewegte, war es, was dann äußerlich die Abtrennung der anthroposophischen Bewegung von der theosophischen bewirkte.

Es ist selbstverständlich für jeden vernünftigen, mit der Bildung der abendländischen Welt ausgerüsteten Menschen, dasjenige, was dazumal als Dogmen auftrat innerhalb der Theosophischen Gesellschaft, als die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft von ihr abgetrennt wurde, es ist ein solches Dogmengezänke über die Präponderanz indischer Weltanschauung oder abendländischer Weltanschauung, eine Diskussion, die so geführt wird, wie sie damals geführt wurde, und vor allen Dingen der Dogmenstreit über einen Inderknaben als zukünftigen Christus, etwas, was nicht ernst zu nehmen ist, was durchaus keinen seriösen Charakter tragen kann, sondern im Grunde genommen auf Nichtigkeiten hinausläuft.

Anthroposophische Bewegung aber ist ihren ursprünglichen Anlagen nach nicht dazu angetan, in theoretischen Streitigkeiten sich zu erschöpfen, sondern sie will unmittelbar in das Leben eintreten, sie will im Leben wirken. Und daher ergab sich die innerliche Trennung von der Theosophischen Gesellschaft, als die Notwendigkeit auftrat, aus den Grundbedingungen anthroposophischer Bewegung heraus allmählich zu künstlerischer, zu sozialer, zu wissenschaftlicher und vor allen Dingen auch zu pädagogischer Wirksamkeit überzugehen. Nicht gleich trat das hervor; aber im Grunde genommen war alles dasjenige, was innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung nach dem Jahre 1912 geschehen ist, nur Dokument dafür, daß diese Bewegung sich ihre selbständige Stellung in der Welt als eine lebenspraktische Bewegung erringen mußte.

Das erste wichtige Aperçu, das sich mir ergab für eine Unmöglichkeit eines innerlichen Zusammengehens mit einer bloßen theosophischen Bewegung, das war mir 1907 vor Augen getreten, als von der Theosophischen Gesellschaft ein Kongreß in München veranstaltet worden ist. Die Dinge festzustellen, die zum Programm dieses Kongresses gehörten, das oblag ja dazumal mir und meinen Freunden von der Deutschen Sektion der theosophischen Bewegung. Wir fügten den traditionellen Programmen, die innerhalb der theosophischen Bewegung figurierten, ein eine Vorstellung eines Mysterienspieles von Edouard Schuré: «Das heilige Drama von Eleusis». Damit vollzogen wir den Übergang von einer bloßen theoretisch-religiösen Bewegung zu einer umfassenderen Weltbewegung, die auch das Künstlerische als einen notwendigen Faktor in sich aufnehmen muß.

Wir hatten, das stellte sich sehr bald heraus, insofern wir auf anthroposophischem Boden standen, die Aufführung des Dramas von Eleusis als etwas Künstlerisches genommen. Von den Persönlichkeiten, welche innerhalb der Bewegung nur die Befriedigung religiöser Gefühle, die manchmal sehr egoistisch sein können, suchten, wurde auch dasjenige, was als ein erster künstlerischer Versuch auftrat, nur im Sinne einer Vorlage für theoretische Interpretation genommen. Man fragte sich daher: Was bedeutet die eine Persönlichkeit des Dramas? Was bedeutet die andere Persönlichkeit? Und man brachte das ganze Drama, man war froh, wenn man das konnte, zuletzt auf eine Art bloßer Terminologie.

Nun, eine Bewegung, die sich in so einseitiger Weise entwickelt, daß sie nicht die volle Lebenspraxis in sich aufnehmen kann, und die sich auf das charakterisierte Gebiet erstreckt, muß notwendigerweise durch sich selbst eine sektiererische Bewegung werden, muß eine Sektenbewegung werden. Anthroposophische Bewegung war vom Anfange an eben nicht dazu veranlagt, eine Sektenbewegung zu werden, denn in ihren Anlagen liegt alles, was zum Gegenteil einer Sektenbewegung führen muß. In ihrer Anlage liegt alles dasjenige, was diese Bewegung zu einer ganz allgemeinen menschlich lebenspraktischen machen muß. Und im Grunde genommen war es das Herausarbeiten aus dem Sektiererischen, was nun mit der zweiten Phase der anthroposophischen Bewegung eintrat, die ich das Hineinarbeiten in das Künstlerische nennen möchte.

Allmählich kam es dann dazu, daß bei einer größeren Anzahl der nun hinzukommenden Anhänger das Bedürfnis entstand, dasjenige, was nur gedacht wird als Philosophie, als Kosmologie, als religiöser Inhalt, auch vor der unmittelbaren Anschauung zu haben. Das kann aber nur, wenn es letztlich befriedigend auftreten soll, in künstlerischer Weise geschehen. Und so trat denn an mich die Notwendigkeit heran, in meinen Mysteriendramen auf künstlerische Weise, zunächst dichterisch, dasjenige zum Ausdrucke zu bringen, was man eigentlich innerhalb solcher Bewegungen bis dahin nur theoretisch zu hören gewöhnt war.

Diese Mysteriendramen dürfen nicht abstrakt theoretisch interpretiert werden. Sie gelten der unmittelbaren künstlerischen Anschauung. Und um diese unmittelbare künstlerische Anschauung unter unseren Anthroposophen zu pflegen, wurden diese Mysterien vom Jahre 1910 bis zum Jahr 1913 in München in der Umrahmung von gewöhnlichen Theatern aufgeführt. Aus alldem heraus entstand dann das Bedürfnis, der anthroposophischen Bewegung ein eigenes Haus zu bauen. Und die verschiedenen Verhältnisse, die es dann untunlich erscheinen ließen, dieses Haus in München aufzuführen, brachten uns zuletzt hier herauf auf den Dornacher Hügel, wo dieses Goetheanum erstand, um allmählich eine der anthroposophischen Bewegung entsprechende Stätte zu werden.

Aber gerade dabei zeigte sich, wie diese anthroposophische Bewegung ihrer ganzen Anlage nach als etwas Allgemein-Menschliches aufgefaßt und gewollt werden muß. Was wäre geschehen, wenn irgendeine andere, theoretische religiöse Bewegung genötigt gewesen wäre, sich ein eigenes Haus zu bauen? Diese Bewegung, das kann man ja in einem solchen Falle leider nicht umgehen, hätte selbstverständlich zunächst Gelder gesammelt bei ihren Freunden, dann hätte man sich an einen Baumeister gewandt, der im antiken oder im Renaissance-, im gotischen oder im Barockstil oder in einem ähnlichen Baustil, der eben traditionell gewesen wäre, einen Bau ausgeführt hätte.

Dies erschien mir in dem Augenblicke, als die anthroposophische Bewegung so glücklich war, zu einem eigenen Haus zu kommen, eine völlige Unmöglichkeit. Denn dasjenige, was innerlich organisch lebensvoll ist, setzt sich niemals aus zwei heterogenen oder aus mehreren heterogenen Stücken zusammen. Was hätte das Wort, das aus anthroposophischem Geiste heraus gesprochen worden wäre, in einem Barock-, in einem antiken oder einem Renaissancebau mit den Formen zu tun gehabt, welche einen dann ringsherum umgeben hätten? Eine theoretische Bewegung ist eben nur imstande, sich durch Ideen, durch Abstraktionen auszusprechen. Eine lebensvolle Bewegung wirkt in alle Zweige des Lebens mit ihren charakteristischen Impulsen hinein. Und was Anthroposophie als Lebens-, Seelen- und Geistespraxis ist, das erfordert, daß die Form, die einem bei der Umhüllung entgegentritt, daß das Malerische, das einem von der Wand entgegenleuchtet, daß die Säulen, die einem entgegentreten, daß alle diese Formen und Farben dieselbe Sprache sprechen, welche theoretisch in Ideen, in abstrakten Gedanken gesprochen wird. Jede solche lebensfähige Bewegung, die in der Welt auftrat, war in dieser Weise umfassend. Die antike Baukunst steht nicht als etwas der antiken Kultur Fremdes gegenüber. Sie ist herausgewachsen aus demjenigen, was im übrigen Theorie und Lebenspraxis war. Ebenso die Renaissance, und ganz besonders zum Beispiel die Gotik, auch das Barock.

Sollte die Anthroposophie nicht etwas Sektiererisches, etwas 'Theoretisches bleiben, so mußte sie zu ihrem eigenen Bau-, zu ihrem eigenen Kunststil kommen. Diesen Bau-, diesen Kunststil, ich sagte es schon, man kann ihn heute noch ungenügend finden oder vielleicht sogar paradox, aber die Tatsache besteht, daß Anthroposophie ihrer ganzen Veranlagung nach nicht anders konnte, als sich ihre eigene, für sie charakteristische Umhüllung schaffen. Lassen Sie mich einen Vergleich gebrauchen, der scheinbar trivial ist, der aber das Wesentliche ausspricht. Nehmen Sie eine Nuß. Sie haben den Kern der Nuß, Sie haben die Schale. Es ist unmöglich, daß bei dem organischen Gebilde der Nuß die Schale aus anderen Kräften hervorgehe als der Kern. Dieselben Kräfte, die den Kern bilden, sie bilden auch die Schale, denn Schale und Kern sind ein Ganzes. So aber wäre es gewesen, wenn von einem fremden Baustile das anthroposophische Wollen eingehüllt worden wäre. Es wäre, wie wenn die Nuß in einer ihr fremden Schale auftreten würde. Dasjenige, was naturhaft ist, und das ist anthroposophische Anschauungsweise, das bringt Kern und Schale hervor, und beides spricht das gleiche aus. So mußte es hier geschehen. So mußte unmittelbar, nicht in eine Symbolik, nicht in eine Allegorie, sondern in unmittelbares künstlerisches Schaffen das anthroposophische Wollen einfließen. Wenn hier in Gedanken gesprochen wird, so sollen diese Gedanken keinen anderen Stil haben als dasjenige, was als Bau- und Kunststil am Goetheanum vorhanden ist. So wuchs wie von selbst anthroposophische Bewegung in künstlerische Bestrebungen hinein.

Es war dies nicht ganz leicht, denn ganz stark machen sich die sektiererischen Tendenzen gerade heute geltend, gerade bei dem nach religiösen Aufschlüssen verlangenden Menschenherzen. Jene innere Freiheit und Offenheit der Seele, die es als selbstverständlich findet, den Übergang zu suchen von demjenigen, was der Seelenorganismus als. religiöse Befriedigung anstrebt, zur äußeren, auch künstlerischen Offenbarung des Geistigen und Seelischen, diese Gesinnung ist vielleicht gerade bei denen wenig zu finden, die in ganz aufrichtiger und inniger Weise in der charakterisierten Art ihre Seelenbefriedigung suchen. Aber anthroposophische Bewegung richtet sich nicht nach den Sympathien und Antipathien dieser oder jener Menschen, sondern anthroposophische Bewegung kann sich nur nach dem richten, was in ihren eigenen Anlagen liegt, die aber allerdings innig zusammenhängen mit den Bedürfnissen und Sehnsuchten des Zeitgeistes, wie wir wohl auch in den nächsten Tagen näher sehen werden.

Und so waren wir daran, in dasjenige praktische Gebiet Anthroposophie hineinzuführen, das uns zunächst zugänglich war. Ich habe in der Zeit, in der wir uns also in die Kunst hineinarbeiteten, manchmal innerhalb des Kreises der Anhänger der anthroposophischen Bewegung ein paradoxes Wort ausgesprochen. Ich habe gesagt: Anthroposophie will auf allen Gebieten in das praktische Leben hinein. — Man läßt uns heute zunächst nicht in die Welt hinein mit der Lebenspraxis, sondern nur in diejenigen Gebiete, die die Welt bedeuten, auf die Bühne oder höchstens in die Kunst, obwohl man da auch viele Türen zuschließt. Aber ich sagte: Am liebsten würde ich aus anthroposophischem Geiste heraus Banken gründen. - Das mag paradox geklungen haben; es sollte nur in seiner paradoxen Art andeuten, wie mir Anthroposophie als das erschien, was nicht nur theoretische oder einseitig religiöse sektiererische Bewegung sein soll, sondern was in alle Gebiete des Lebens befruchtend hineinwirken soll und nach meiner Überzeugung auch kann.

Damit wären wir an diejenige Zeit herangekommen, welche aus dem allgemeinen katastrophalen Menschenchaos heraus ganz besondere Bedürfnisse für die gegenwärtige Menschheit zeitigte, wir waren herangelangt bis zu der furchtbaren Kriegskatastrophe. 1913, im September, hatten wir den Grundstein zu diesem Bau gelegt. 1914 waren wir mit seinem Anfange beschäftigt, als die Kriegskatastrophe über die Menschheit hereinbrach. In diesem Zusammenhange will ich nur sagen, daß in der Zeit, in der Europa in nationale Aspirationen gespalten war, die wenig und immer weniger Berührungspunkte miteinander hatten, daß es uns in dieser Zeit hier in Dornach gelungen ist, immerdar während des ganzen Kriegsverlaufes eine Stätte zu haben, in der sich Persönlichkeiten aller Nationalitäten begegnen konnten und in ausgiebigem Maße auch wirklich zum Zusammenwirken in Frieden und im Geiste sich zusammenfanden. Das war etwas, was von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus mit tiefer Befriedigung erfüllen konnte, daß hier im Goetheanum eine Stätte war, wo, während die Nationen sich sonst zerfleischten und verbluteten, sich Angehörige aus allen europäischen Nationen zu friedwärtigem geistigem Zusammenarbeiten fanden. Damit habe ich Ihnen die zweite Phase unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung charakterisiert.

Während der Kriegsdauer war ja das äußere Wirken der anthroposophischen Bewegung vielfach gelähmt. So viel innerhalb ihrer geleistet werden konnte, wurde aber versucht. Ganz abgesehen aber von diesen äußeren Vorgängen konnte man durch die ganze Kriegsdauer hindurch sehen, wie innerhalb weiter Menschheitskreise das Bedürfnis nach solchen Erkenntnissen wuchs, wie sie nach meiner Überzeugung durch die Anthroposophie gegeben werden können. Und man kann sagen, nachdem die Kriegskatastrophe zunächst 1918 einen äußerlichen Abschluß gefunden hatte, war in einem unbegrenzten Maße das Interesse für eine solche Bewegung, wie sie die anthroposophische sein will, gewachsen. Dann aber, als der Herbst 1918 hereinbrach und das Frühjahr 1919, da kamen zunächst eine Anzahl von Freunden aus Deutschland zu mir, speziell aus Stuttgart, und die Aspirationen dieser Freunde leiteten eigentlich die dritte Phase unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung ein. Denn aus diesen Aspirationen heraus war die anthroposophische Bewegung genötigt, gewissermaßen ihre Impulse nun auch in das soziale Leben der Menschheit im weitesten Umfange hineinzustrahlen.

Ein anderes Gebiet als Deutschland und speziell Süddeutschland, Württemberg, war ja der anthroposophischen Bewegung in diesem Zeitraume nicht zugänglich. Aber man wollte innerhalb desjenigen Gebietes wirken, innerhalb dessen sich eben wirken ließ. Und dieses Wirken hatte selbstverständlich in der Zeit seines Auftretens auf sozialem Gebiete eine gewisse Farbnuance angenommen von dem, was gerade in Süddeutschland das damals Maßgebliche war. Und dieses Maßgebliche war eigentlich das soziale Chaos. Man kann schon sagen, ein . unbeschreibliches Elend auch in physisch-materieller Beziehung lastete dazumal über Mitteleuropa. Aber selbst dieses unermeßlich große physisch-materielle Elend war eigentlich für den, der solche Dinge unbefangen zu beobachten vermag, klein gegenüber der seelischen Not. Diese seelische Not hatte ja auch die Menschheit gerade in bezug auf das soziale Wollen in eine Art von Chaos auf diesem Gebiete geworfen. Man fühlte, in bezug auf das soziale Leben war die Menschheit vor die allerursprünglichsten Fragen der Menschheitsentwickelung überhaupt gestellt. Die Fragen, die einst Rousseau aufgeworfen hat, die Fragen, welche dann eine äußere Gestaltung in der Französischen Revolution erfahren haben, sie rührten nicht so stark an die ursprünglichsten, elementarsten menschlichen Sehnsuchten und Bedürfnisse, wie die Fragen, die eigentlich im Jahre 1919 auf den Gebieten da waren, auf denen wir gerade zu wirken hatten.

Alles, was seit Jahrhunderten den sozialen Organismus, wie er sich aus den verschiedenen Völkerschaften heraus gebildet hat, konstituierte, das kam in Frage. Und aus dieser Stimmung heraus entstand sowohl mein kurzer «Aufruf» über die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus «an das deutsche Volk und an die Kulturwelt», wie auch mein Buch «Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage in den Lebensnotwendigkeiten der Gegenwart und Zukunft», und aus dieser Stimmung heraus entstand dann alles dasjenige, was zunächst innerhalb Süddeutschlands an Behandlung der sozialen Frage unternommen worden ist. Damals war es im Grunde genommen notwendig, aber ungeheuer schwierig, an die Elementarsehnsuchten der menschlichen Herzen zu rühren. Die Menschen mußten aus physischem und seelischem Elend heraus abstrakt nach einem Größten suchen, und nach der Verfassung der Zeit waren sie unfähig dazu. Und gar mancher sagte mir am Schlusse dieser oder jener Rede, die ich gehalten habe: Das mag alles schön sein, aber es beschäftigt sich ja damit, wie es in der Zukunft unter den Menschen ausschauen soll; wir sind so oft dem Tode gegenübergestanden in den letzten Jahren, daß uns das Denken über die Zukunft gleichgültig geworden ist. Warum sollten wir jetzt mehr Interesse der Zukunft entgegenbringen, als wir ihr entgegenbringen durften, als die Kanonen auf unsere Leiber gerichtet waren! - So ungefähr charakterisierte man immer wiederum die durch das Elend und die Not gegebene Interesselosigkeit gegenüber dem Notwendigsten in der Menschheitsentwickelung.

Aus dem, was dazumal meiner Freunde Herzen und Seelen bewegte, entstand dann, ich möchte es nennen ein Spezialgebiet sozialen Wirkens, indem man sich sagte: Für die Zukunft kann man vielleicht nur in der wirksamen Weise vorarbeiten, wenn man sich an die Jugend, wenn man sich an die Kindheit der Menschheit wendet. — Und unser Freund Emil Molt in Stuttgart, der selbst Fabrikant und Unternehmer ist, trat in den Dienst gerade eines solchen Wollens. Er begründete zunächst mit den Kindern seiner Waldorf-Astoria-Fabrik die Waldorfschule in Stuttgart, und mir wurde zunächst die pädagogisch-didaktische Durchführung des Waldorfschul-Planes übertragen.

Man hatte in der Zeit, die der Kriegskatastrophe vorangegangen ist, viel erlebt an allerlei Erziehungs- und pädagogischen Versuchen. Hier handelte es sich nicht um die Begründung von Landerziehungsheimen, nicht um die Begründung irgendwelcher, aus Partialwünschen hervorgehender Sonderschulbestrebungen, hier handelte es sich um etwas, was im ganzen Rahmen des sozialen Menschheitsstrebens gelegen ist. Wir werden ja über all diese Grundlagen einer Waldorfschul-Pädagogik in den nächsten Tagen zu sprechen haben. Hier will ich nur so viel andeuten, daß Anthroposophie, wie sonst, so auch hier genötigt war, mit der Realität, mit der vollen Realität zu rechnen. Wir konnten nicht irgendwo in der schönen freien Waldnatur draußen ein Landerziehungsheim gründen, wo man alles dasjenige machen kann, was einem gefällt; wir hatten ganz bestimmte reale Verhältnisse zunächst. Wir hatten die Kinder einer Kleinstadt, mußten eine Schule in der Kleinstadt begründen, waren angewiesen darauf, dasjenige, was durch diese Schule auch vielleicht mit den sozial höchsten Zielen geleistet werden sollte, aus rein pädagogisch-didaktischer Fundierung heraus zu leisten. Wir konnten uns weder Lokalität noch Schüler aussuchen etwa nach Ständen oder Klassen. Wir hatten fest gegebene Verhältnisse und waren angewiesen darauf, dasjenige, was wir tun konnten, aus dem Geiste heraus zu tun. So entstand als eine ganz notwendige Konsequenz der anthroposophischen Bewegung ihr Wirken auf pädagogisch-didaktischem Gebiete, das uns ja.in den nächsten Tagen ganz besonders beschäftigen soll.

Die Waldorfschule in Stuttgart, die nun längst nicht mehr das ist, was sie im Anfang war, nämlich eine Schulanstalt für die Kinder der Waldorf-Astoria-Zigarettenfabrik, diese Waldorfschule ist schnell eine Schule für alle Stände geworden, und von überallher strebt man heute schon darnach, die Kinder in diese Waldorfschule zu bringen. Von hundertvierzig Kindern, mit denen wir die Schule begründet haben, ist sie jetzt angewachsen zu sechshundert Kindern, und die Anmeldungen stellen sich jedesmal in erhöhter Zahl ein. Wir haben in den letzten Tagen den Grundstein zu einem Neubau für diese Schule legen müssen und hoffen, daß wir sie trotz aller Schwierigkeiten, die heute gerade einem solchen Wirken gegenüberstehen, immerhin doch zu gewissen Entfaltungsmöglichkeiten bringen können.

Aber betonen muß ich, daß das Wesentliche dieser Schule in dem Pädagogisch-Didaktischen liegt, in der Anpassung dieses PädagogischDidaktischen an die gegebenen realen Verhältnisse des Lebens, in dem Sich-Halten an die unmittelbare Lebenspraxis. Wenn man sich die Klasse auswählen kann, aus der man die Schüler nimmt, wenn man sich die Lokalität der Schule auswählen kann, so ist es eben ein leichtes, damit eine eingebildete oder vielleicht auch eine wirkliche Schulreform durchzuführen; es stellt aber eben Aufgaben, welche wiederum zusammenhängen mit den Urimpulsen alles Menschlichen, wenn aus rein pädagogisch-didaktischer Fundierung eine solche Schule gegründet und weitergeführt werden soll.

Damit aber war während der dritten Phase unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung diese Bewegung ausgedehnt worden auf das soziale und das pädagogische Gebiet. Und wegen dieses letzteren sind Sie ja hierher gekommen, und dieses pädagogische Gebiet wird uns in den nächsten Tagen ganz besonders zu beschäftigen haben. Es ist tatsächlich erst der Anfang gemacht worden damit, in der äußeren Wirklichkeit auszubauen, was der anthroposophischen Bewegung durch ihre Anlagen von allem Anfange an als ihr Fundament gegeben war.

Zu dem, was dann hinzugekommen ist, gehört, daß eine große Anzahl von Menschen in den letzten Jahren mit wissenschaftlicher Bildung und mit wissenschaftlichen Aspirationen sich gefunden haben, welche einsahen, daß die anthroposophische Bewegung auch das unmittelbar wissenschaftliche Leben der Neuzeit befruchten kann. Mediziner fanden sich, welche durchdrungen waren davon, daß die an die äußere Beobachtung und an das äußere Experiment allein sich haltende Naturwissenschaft den gesunden und kranken menschlichen Organismus nicht in seiner Totalität zu begreifen vermag. Ärzte fanden sich, welche die zu überwindenden Grenzen der heute geltenden Medizin in dieser Art tief empfanden, vor allen Dingen die Kluft tief empfanden, welche heute für die anerkannte Medizin besteht zwischen der Pathologie und Therapie. Pathologie und Therapie stehen heute wie unvermittelt nebeneinander. Anthroposophie, die ihre Erkenntnisse nicht nur durch das äußere Experiment, durch die Beobachtung und den kombinierenden Verstand sucht, sondern mit denjenigen Mitteln, die ich in den nächsten Tagen charakterisieren werde, sie betrachtet den Menschen nach Leib, Seele und Geist, und faßt den Geist in seiner Lebendigkeit, nicht in seiner Abstraktion als eine Summe von Gedanken, wie das in der neueren Zeit üblich geworden ist. Damit aber konnte Anthroposophie den Aspirationen gerade solcher Menschen entgegenkommen, die zum Beispiel aus der Medizin heraus eine Befruchtung ihres Gebietes heute dringend suchen. Und so kam es, daß ich zwei Lehrkurse für akademische Mediziner und praktizierende Ärzte hier in Dornach zu halten hatte über dasjenige, was Anthroposophie für Pathologie und Therapie zu leisten imstande ist. Sowohl hier in Dornach, in Arlesheim drüben, wie auch in Stuttgart, sind medizinisch-therapeutische Institute entstanden, welche mit eigenen Heilmitteln arbeiten, welche vor allen Dingen das praktisch fruchtbar zu machen versuchen, was aus Anthroposophie für die Menschenheilung, für Menschengesundheit und Krankheit kommen kann.

Und auch von anderer Seite haben die einzelnen Wissenschaften die Befruchtung gesucht durch die Anthroposophie. Physikalische, astronomische Kurse mußten gehalten werden. Nach den verschiedensten wissenschaftlichen Gebieten hin mußte von der Anthroposophie heraus das geleistet werden, was eben aus einer wirklichen Geist-Erkenntnis für die heutige Wissenschaft geleistet werden kann.

Diese dritte Phase der anthroposophischen Bewegung charakterisiert sich gerade dadurch, daß man da, wo man streng wissenschaftliche Fundierung fordert, allmählich, wenn das auch heute noch vielfach angefochten ist, dennoch findet, daß diejenige Geisteswissenschaft, wie sie hier gepflegt wird, jeder wissenschaftlichen Forderung nach Fundierung genügen kann, daß die Anthroposophie, die hier gemeint ist, mit voller Strenge und im vollen Einklange mit jedem wissenschaftlichen Ernste arbeiten kann. Indem dieses immer mehr und mehr wird eingesehen werden, wird man verstehen, was in der anthroposophischen Bewegung eigentlich von vornherein vor zwanzig Jahren wenigstens veranlagt war.

Daß die verschiedensten Gebiete befruchtet werden können durch Anthroposophie, es zeigt sich ja auch dadurch, daß wir in der Lage waren, in unserer Eurythmie eine besondere Bewegungskunst zu begründen, eine Kunst, welche sich des Menschen selber als ihres Ausdrucksmittels, als ihres Instrumentes bedient, und welche gerade dadurch zu ihren besonderen Wirkungen zu kommen sucht. — So versuchen wir auch auf anderen Gebieten, ich werde davon noch zu reden haben im Laufe der nächsten Tage, zum Beispiel auf dem Gebiete der Rezitations- und Deklamationskunst eine Befruchtung herbeizuführen durch dasjenige, was genannt werden darf nicht anthroposophische Theorie, sondern anthroposophisches Leben.

Und so ist vielleicht doch diese letzte Phase der anthroposophischen Bewegung mit ihrem pädagogischen, medizinischen, ihrem künstlerischen Einschlage dasjenige, was am meisten für Anthroposophie charakteristisch ist. Anhänger hat die Anthroposophie gefunden; Gegner, wütende Gegner hat sie gefunden; aber sie ist einmal in der Gegenwart in dasjenige Stadium ihres Wirkens eingetreten, das sie eigentlich suchen muß. Und so war es für mich befriedigend, daß es während meines Aufenthaltes in Kristiania vom 23. November bis zum 4. Dezember dieses Jahres möglich war, das anthroposophische Leben zur Sprache zu bringen innerhalb pädagogischer Gesellschaften, innerhalb staatsökonomischer Gesellschaften, innerhalb der Studentenschaft Norwegens und auch innerhalb weitester Kreise, solcher Kreise, die durchaus gewillt sind, nicht bloß eine Theorie, ein religiöses Sektiererisches entgegenzunehmen, sondern schon dasjenige, was aus dem unmittelbaren Geist unserer Zeit als eine große Menschheitsforderung heute innerhalb der Welt sich offenbaren will.

Diese drei Phasen hat die anthroposophische Bewegung in ihrer Entwickelung aufzuweisen. Indem ich sie kurz vor Ihnen skizzierte, meine Damen und Herren, habe ich vielleicht in einer ausführlicheren Weise zunächst nur den Namen genannt für die anthroposophische Bewegung. Allein das ist es ja, was ich wollte. Ich wollte Ihnen diese anthroposophische Bewegung heute zunächst einleitungsweise vorstellen, das heißt, vor Ihnen ihren Namen nennen, und ich werde mir erlauben, auf unser eigentliches Thema von morgen ab vor Ihnen einzutreten. Diese anthroposophische Bewegung als solche, insbesondere aber mit ihren pädagogisch-didaktischen Konsequenzen, sie ist es, welche Ihnen aus tiefbefriedigter Seele über Ihren Besuch heute den ersten Gruß entgegenbringen wollte.

First Lecture

Before the educational course began, Rudolf Steiner addressed the participants gathered in the “white hall” of the first Goetheanum with the following words:

“Ladies and gentlemen, before I begin my discussions, allow me to raise an administrative matter.

The course was originally intended for a small group, but now it has attracted so many participants that it is clear we will not be able to complete the course in the intended manner if we are all sitting here in this crowded hall. That would be impossible; you would notice this if you were here during the lecture and during the translation. Therefore, I have decided to hold the course twice, the first time every day at 10 a.m., and then, especially for those who wish to participate in the translation, because technically there is no other way, at 11 a.m. So I will begin the first lecture every day punctually at 10 a.m., and then repeat it at 11 a.m. I would ask that you perhaps arrange things so that all those present who are from England, Holland, and Scandinavia attend the second lecture, and the others attend the first.”

The first words I utter are to be words of heartfelt joy and deep satisfaction at your visit, ladies and gentlemen. Anyone who is most enthusiastic about the movement that wishes to take its starting point here at the Goetheanum must be deeply delighted and profoundly satisfied by the interest you have shown in such an extraordinary way through your visit. And out of this joy and satisfaction, allow me to welcome you here today in the warmest possible way at the beginning of this introductory lecture.

In particular, I would like to welcome Professor Mackenzie, whose efforts have succeeded in inaugurating this course, and to whom I therefore owe a special debt of gratitude on behalf of the anthroposophical movement. But I welcome you all most warmly in the spirit and meaning of our movement. And, ladies and gentlemen, it is not only an individual personality who welcomes you here, but above all the building itself, the Goetheanum.

I fully understand that some of you may have criticisms of the Goetheanum as a building, as a work of art. However, everything that comes into the world in this way is naturally subject to criticism, and any objections that come from good intentions will be most welcome, especially to me. Nevertheless, this Goetheanum welcomes you, and its form and artistic design will show you that it is not only a matter of inaugurating a single area of human life, nor is it a matter of focusing solely on the field of education. The whole spirit of this building and the existence of this building can show you that this is a movement for our entire civilization, conceived and desired out of the spirit of our time. And insofar as education and teaching are essential parts of human civilization, education and teaching in particular must also find their special care here.

The intimate relationship between anthroposophical will and questions of education and teaching will be presented to us in detail over the next few days. But today, allow me to add something to the warmest greetings I offer you, something that, in a sense, is self-evident on the basis of a social movement.

You have come here, in a sense, to find out about the movements that originate from the Goetheanum in Dornach. As I warmly welcome you as guests to this Goetheanum, I feel obliged, as is usually the case in social interactions, to first introduce you to the movement that originated here.

What has been intended with this anthroposophical movement since its inception twenty years ago is only now slowly coming to light. Basically — as you will see from the following lectures — this movement was conceived from the outset as what it is perceived to be today by the world, both in a positive and, above all, in a negative sense. Only now are people beginning to speak of this anthroposophical movement as it was originally intended. However, this anthroposophical movement has gone through many different phases, and it will be easiest for me to introduce this movement to you, at least outwardly, by describing these phases.

Initially, the anthroposophical movement was taken by the small circle that professed it as a kind of religious worldview in the narrower sense. People who were not particularly concerned with scientific foundations, who were not particularly concerned with artistic expressions and with the consequences of anthroposophical life practice for social life as a whole, were the first to approach this anthroposophical movement. People who, above all, felt dissatisfied with current traditional religious beliefs, people who were searching for something that came from the deepest human longings in relation to the great questions of the human soul and the human spirit, people who felt deeply dissatisfied with the traditional ideas of existing religious beliefs in relation to these questions, were drawn to this movement, and they initially embraced this movement with their feelings, with their sensibilities.

For me personally, it was often astonishing to see how what I had to say about anthroposophy was not really understood by its followers in terms of its foundations, but how this anthroposophical movement was met with sympathy and support based on simple and elementary human feelings. From what was basically a scientific orientation from the outset, these first followers heard what spoke to their hearts, what spoke to their immediate feelings, to their sensibilities. And one can say that this was the quietest time — although quietness in this direction is not always desirable — this was the quietest time of the anthroposophical movement.

Because this was the case, this anthroposophical movement could initially be accepted and go along — purely externally, however, in terms of mere administrative participation — with the movement that you may know as the Theosophical Society.

People who, in the manner described, search from their simple hearts for the questions of the eternal in human nature, ultimately find satisfaction in both the theosophical movement and the anthroposophical movement, even if they overlook some essential and fundamental aspects. However, the theosophical movement was oriented from the outset toward a certain purely theoretical aspect. The theosophical movement aims to be a teaching expressed in words, encompassing cosmology, philosophy, and religion, and insofar as cosmology, philosophy, and religion can be proclaimed through words, the theosophical movement aims to live itself out. People who are actually satisfied with their life situation in relation to other circumstances and only want to hear something different about the questions of the eternal than what traditional religious confessions can provide often find satisfaction in both movements in the same way. And only when it became apparent, although little noticed at the time, that anthroposophy wanted to be something that did not merely indulge in cosmology, philosophy, and religion in a theoretical way, but which, in accordance with the demands of the current zeitgeist, had to intervene in real life in all areas, it gradually became clear for internal reasons that it was impossible for the anthroposophical movement to continue to work together with the theosophical movement. For today — as we will see in the following lectures — any kind of movement that limits itself to these three areas, cosmology, philosophy, and religion, in a more theoretical sense, degenerates into an ultimately intolerable quarrel over dogma. And it was a dogmatic dispute, which was basically about trivialities, that then brought about the external separation of the anthroposophical movement from the theosophical movement.

It is self-evident to any reasonable person educated in the Western world that what appeared as dogma within the Theosophical Society when the Anthroposophical Society separated from it such dogmatic squabbling about the preponderance of the Indian worldview or the Western worldview, a discussion conducted as it was conducted at that time, and above all the dogmatic dispute about an Indian boy as the future Christ, is something that cannot be taken seriously, that cannot possibly be regarded as serious, but basically amounts to trivialities.

However, the anthroposophical movement, in accordance with its original intentions, is not inclined to exhaust itself in theoretical disputes, but wants to enter directly into life, it wants to have an effect on life. And so the inner separation from the Theosophical Society came about when the need arose to gradually move from the basic conditions of the anthroposophical movement to artistic, social, scientific, and above all, educational activity. This did not happen immediately, but basically everything that happened within the anthroposophical movement after 1912 was merely evidence that this movement had to gain its independent position in the world as a practical movement.

The first important insight I had into the impossibility of an inner connection with a purely theosophical movement came to me in 1907, when the Theosophical Society held a congress in Munich. It was up to me and my friends from the German section of the theosophical movement to determine the agenda for this congress. We added to the traditional programs that featured within the theosophical movement a performance of a mystery play by Edouard Schuré: “The Sacred Drama of Eleusis.” In doing so, we made the transition from a purely theoretical-religious movement to a more comprehensive world movement, which must also incorporate the artistic as a necessary factor.

It soon became clear that, insofar as we stood on anthroposophical ground, we had taken the performance of the drama of Eleusis as something artistic. Those within the movement who sought only the satisfaction of religious feelings, which can sometimes be very selfish, took what appeared to be a first artistic attempt only as a template for theoretical interpretation. They therefore asked themselves: What does one character in the drama mean? What does the other character mean? And the whole drama was ultimately reduced to a kind of mere terminology, which people were happy to do if they could.

Now, a movement that develops in such a one-sided way that it cannot absorb the full practice of life, and which extends to the characterized area, must necessarily become a sectarian movement, must become a sectarian movement. From the beginning, the anthroposophical movement was not predisposed to become a sectarian movement, because its foundations contain everything that must lead to the opposite of a sectarian movement. Its foundations contain everything that must make this movement a very general, practical human movement. And basically, it was the working out of the sectarian that now entered with the second phase of the anthroposophical movement, which I would like to call the working into the artistic.

Gradually, a large number of the new followers felt the need to have what was only thought of as philosophy, cosmology, or religious content, also available for immediate observation. However, if this is to be ultimately satisfying, it can only be done in an artistic way. And so I felt the need to express in my mystery dramas, in an artistic way, initially poetically, what until then had only been heard theoretically within such movements.

These mystery dramas must not be interpreted in an abstract, theoretical way. They are intended for direct artistic perception. And in order to cultivate this direct artistic perception among our anthroposophists, these mysteries were performed in Munich from 1910 to 1913 in the setting of ordinary theaters. All of this gave rise to the need to build a home for the anthroposophical movement. And the various circumstances that made it impractical to build this home in Munich ultimately brought us up here to the Dornach hill, where this Goetheanum was built, gradually becoming a place befitting the anthroposophical movement.

But this is precisely where it became apparent that the anthroposophical movement, in its entirety, must be understood and desired as something universal and human. What would have happened if some other theoretical religious movement had been compelled to build its own house? In such a case, this movement would, of course, first have collected funds from its friends, then turned to a builder who would have constructed a building in the ancient or Renaissance, Gothic or Baroque style, or in a similar architectural style that would have been traditional.

This seemed to me, at the moment when the anthroposophical movement was so fortunate as to acquire its own building, to be a complete impossibility. For that which is organically alive within never consists of two or more heterogeneous parts. What would the word, spoken from the anthroposophical spirit, have had to do with the forms that would have surrounded it in a Baroque, antique, or Renaissance building? A theoretical movement is only capable of expressing itself through ideas, through abstractions. A movement full of life influences all branches of life with its characteristic impulses. And what anthroposophy is as a practice of life, soul, and spirit requires that the form that confronts one in the envelope, that the painterly that shines out from the wall, that the columns that confront one, that all these forms and colors speak the same language that is spoken theoretically in ideas, in abstract thoughts. Every such viable movement that occurred in the world was comprehensive in this way. Ancient architecture does not stand as something foreign to ancient culture. It grew out of what was otherwise theory and life practice. The same is true of the Renaissance, and especially, for example, the Gothic and Baroque periods.

If anthroposophy was not to remain something sectarian, something ‘theoretical’, it had to develop its own architectural and artistic style. This architectural style, this artistic style, as I have already said, may still be considered inadequate or perhaps even paradoxical today, but the fact remains that anthroposophy, given its entire disposition, could not help but create its own characteristic envelope. Let me use a comparison that may seem trivial, but which expresses the essence of the matter. Take a nut. You have the kernel of the nut, you have the shell. It is impossible for the shell of the nut, as an organic structure, to arise from forces other than those that form the kernel. The same forces that form the kernel also form the shell, for shell and kernel are one. But that is what would have happened if anthroposophical will had been enveloped in a foreign architectural style. It would have been as if the nut appeared in a shell that was foreign to it. That which is natural, and that is the anthroposophical way of looking at things, produces the kernel and the shell, and both express the same thing. This is how it had to be here. The anthroposophical will had to flow directly into immediate artistic creation, not into symbolism or allegory. When thoughts are expressed here, these thoughts should have no other style than that which is present in the architectural and artistic style of the Goetheanum. In this way, the anthroposophical movement grew into artistic endeavors as if by itself.

This was not entirely easy, because sectarian tendencies are particularly strong today, especially in the hearts of people who long for religious enlightenment. That inner freedom and openness of soul which finds it natural to seek the transition from what the soul organism strives for as religious satisfaction to the outer, artistic revelation of the spiritual and soul life – this attitude is perhaps least to be found in those who seek soul satisfaction in the manner described, in a completely sincere and heartfelt way. But the anthroposophical movement is not guided by the sympathies and antipathies of this or that person; rather, the anthroposophical movement can only be guided by what lies in its own predispositions, which are, however, closely connected with the needs and longings of the spirit of the times, as we will see more clearly in the coming days.

And so we were in the process of introducing ourselves to the practical field of anthroposophy that was initially accessible to us. During the time when we were working our way into art, I sometimes uttered a paradoxical statement within the circle of followers of the anthroposophical movement. I said: Anthroposophy wants to enter practical life in all areas. — Today, we are not allowed to enter the world with the practice of life, but only in those areas that mean the world, on the stage or at most in art, although many doors are closed there as well. But I said: I would most like to found banks out of the anthroposophical spirit. That may have sounded paradoxical; it was only meant to indicate, in its paradoxical way, how anthroposophy appeared to me as something that should not only be a theoretical or one-sided religious sectarian movement, but something that should have a fruitful effect on all areas of life and, in my conviction, can do so.

This brings us to the time when the general catastrophic chaos of humanity gave rise to very special needs for the people of that time; we had reached the terrible catastrophe of war. In September 1913, we laid the foundation stone for this building. In 1914, we were busy with its construction when the catastrophe of war broke out over humanity. In this context, I would just like to say that at a time when Europe was divided by national aspirations, which had little and less and less in common with each other, we succeeded here in Dornach in to have a place throughout the entire war where personalities of all nationalities could meet and, to a large extent, really come together to work together in peace and in spirit. From a certain point of view, it was deeply satisfying that here at the Goetheanum there was a place where, while the nations were otherwise tearing each other apart and bleeding each other dry, members of all European nations found each other in peaceful spiritual cooperation. With this I have characterized the second phase of our anthroposophical movement.

During the war, the external activities of the anthroposophical movement were largely paralyzed. However, every effort was made to achieve as much as possible within its confines. Quite apart from these external events, however, it was possible to see throughout the war how the need for such insights, which I am convinced can be provided by anthroposophy, grew within broad circles of humanity. And it can be said that after the catastrophe of the war had come to an external conclusion in 1918, interest in a movement such as anthroposophy aspires to be had grown immeasurably. But then, as autumn 1918 and spring 1919 approached, a number of friends from Germany, especially from Stuttgart, came to me, and the aspirations of these friends actually initiated the third phase of our anthroposophical movement. For out of these aspirations, the anthroposophical movement was compelled, as it were, to radiate its impulses into the social life of humanity in the broadest sense.