The Kingdom of Childhood

GA 311

16 August 1924, Torquay

Lecture V

It will be essential for you to have some understanding of the real essence of every subject that you teach, so that you do not make use of things in your teaching that are remote from life itself. Everything which is intimately connected with life can be understood. One could even say that whatever one really understands has this intimate connection with the life of man. This is not the case with abstractions.

What we find today is that the ideas a teacher has are largely abstractions, so that in many respects he is himself remote from life. This brings very great difficulties into education and teaching. Just consider the following: Imagine that you want to think over how you first came to count things and what really happens when you count. You will probably find that the thread of your recollections breaks somewhere, and that you did once learn to count, but actually you do not really know what you do when you count.

Now all kinds of theories are thought out for the teaching of number and counting, and it is customary to act upon such theories. But even when external results can be obtained, one does not touch the whole being of the child with this kind of counting or with similar things that have no connection with real life. The modern age has proved that it lives in abstractions, by inventing such things as the abacus or bead-frame for teaching. In a business office people can use calculating machines as much as they like—that does not concern us at the moment, but in teaching, this calculating machine, which is exclusively concerned with the activities of the head, prevents one from the very start from dealing with number in a way which is in accordance with the child nature.

Counting however should be derived from life itself, and here it is supremely important to know from the beginning that we should not ever expect the child to understand every single thing we teach him. He must take a great deal on authority, but he must take it in a natural, practical way.

Perhaps you may find that what I am now going to say will be rather difficult for the child. But that does not matter. It is of great significance that there should be moments in a man's life when in his thirtieth or fortieth year he can say to himself: Now I understand what in my eighth or ninth year, or even earlier, I took on authority. This awakens new life in a man. But if you look at all the object lessons that are introduced into the teaching of today, you may well be in despair over the way things are made trivial, in order, as one says, to bring them nearer to the child's understanding.

Now imagine that you have quite a small child in front of you, one of the youngest, who is still quite clumsy in his movements, and you say to him: “You are standing there before me. Here I take a piece of wood and a knife, and I cut the wood into pieces. Can I do that to you?” The child will see for himself that I cannot do it to him. And now I can say to him: “Look, if I can cut the piece of wood in two, the wood is not like you, and you are not like the wood, for I cannot cut you in two like that. So there is a difference between you and the wood. The difference lies in the fact that you are a unit, a ‘one,’ and the wood is not a ‘one.’ You are a unit and I cannot cut you in two, and therefore I call you ‘one,’ a unit.”

You can now gradually proceed to show the child a sign for this “one.” You make a stroke: I, so that you show him it is a unit and you make this stroke for it.

Now you can leave this comparison between the wood and the child and you can say: “Look, here is your right hand but you have another hand too, your left hand. If you only had this one hand it could certainly move about everywhere as you do, but if your hand were only to follow the movement of your body you could never touch yourself in the way in which your two hands can touch each other. For when this hand moves and the other hand moves too at the same time, then they can take hold of each other, they can come together. That is different from when you simply move alone. In that you walk alone you are a unit. But the one hand can touch the other hand. This is no longer a unit, this is a duality, a ‘two.’ See, you are one, but you have two hands.” This you then show like this: II.

In this way you can work out a conception of the “one” and the “two” from the child's own form.

Now you call out another child and say: “When you two walk towards each other you can also meet and touch each other; there are two of you, but a third can join you. This is impossible with your hands.” Thus you can proceed to the three: III.

In this manner you can derive number out of what man is himself. You can lead over to number from the human being, for man is not an abstraction but a living being.

Then you can pass on and say: “Look, you can find the number two somewhere else in yourself.” The child will think finally of his two legs and feet. Now you say: “You have seen your neighbour's dog, haven't you? Does he only go on two feet also?” Then he will come to realise that the four strokes IIII are a picture of the neighbour's dog propped up on four legs, and thus he will gradually learn to build up number out of life.

The teacher must have his eyes open wherever he goes and look at everything with understanding. Now we naturally begin to write numbers with the Roman figures, because these of course will be immediately understood by the child, and when you have got to the four you will easily be able, with the hand, to pass over to five—V. You will soon see that if you keep back your thumb you can use this four as the dog does!: I I I I. Now you add the thumb and make five—V.

I was once with a teacher who had got up to this point (in explaining the Roman figures) and could not see why it occurred to the Romans not to make five strokes next to one another but to make this sign V for the five. He got on quite well up to I I I I. Then I said: “Now let us do it like this: Let us spread out our fingers and our thumb so that they go in two groups, and there we have it, V. Here we have the whole hand in the Roman five and this is how it actually originated. The whole hand is there within it.”

In a short lecture course of this kind it is only possible to explain the general principle, but in this way we can derive the idea of number from real life, and only when number has thus been worked out straight from life should you try to introduce counting by letting the numbers follow each other. But the children should take an active part in it. Before you come to the point of saying: Now tell me the numbers in order, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and so on, you should start with a rhythm; let us say we are going from 1 to 2, then it will be: 1, 2; 1, 2; 1, 2; let the child stamp on 2 and then on to 3 also in rhythm: 1, 2, 3; 1, 2, 3. In this way we bring rhythm into the series of numbers, and thereby too we foster the child's faculty of comprehending the thing as a whole. This is the natural way of teaching the children numbers, out of the reality of what numbers are. For people generally think that numbers were thought out by adding one to the other. This is quite untrue, for the head does not do the counting at all. In ordinary life people have no idea what a peculiar organ this human head really is, and how useless for our earthly life. It is there for beauty's sake, it is true, because our faces please each other. It has many other virtues too, but as far as spiritual activities are concerned it is really not nearly so much in evidence, for the spiritual qualities of the head always lead back to man's former earth-life. The head is a metamorphosis of the former life on earth, and the fact of having a head only begins to have a real meaning for man when he knows something of his former earth lives. All other activities come from somewhere else, not from the head at all. The truth is that we count subconsciously on our fingers. In reality we count from 1-1 o on our ten fingers, then eleven (adding the toes), twelve, thirteen, fourteen (counting on the toes). You cannot see what you are doing, but you go on up to twenty. And what you do in this manner with your fingers and toes only throws its reflection into the head. The head only looks on at all that occurs. The head in man is really only an apparatus for reflecting what the body does. The body thinks, the body counts. The head is only a spectator.

We can find a remarkable analogy for this human head. If you have a car and are sitting comfortably inside it, you are doing nothing yourself; it is the chauffeur in front who has to exert himself. You sit inside and are driven through the world. So it is with the head; it does not toil and moil, it simply sits on the top of your body and lets itself be carried quietly through the world as a spectator. All that is done in spiritual life is-done from the body. Mathematics are done by the body, thinking is also done by the body, and feeling too is done with the body. The bead-frame has arisen from the mistaken idea that man reckons with his head. Sums are then taught to the child with the bead-frame, that is to say, the child's head is made to work and then the head passes on the work to the body, for it is the body which must do the reckoning. This fact, that the body must do the reckoning, is not taken into account, but it is important. So it is right to let the child count with his fingers and also with his toes, for indeed it is good to call forth the greatest possible skill in the children. In fact there is nothing better in life than making the human being skilful in every way. This cannot be done through sport, for sport does not really make people skilled. What does make a man skilled is to give him a pencil, for instance, and let him hold it between his big toe and the next toe and learn to write with his foot, to write figures with his foot. This can be of real significance, for in truth man is permeated with soul and spirit in his whole body. The head is the traveller that sits back restfully inside and does nothing, whilst the body, every part of it, is the chauffeur who has to do everything.

Thus from the most varied sides you must try to build up what the child has to learn as counting. And when you have worked in this way for a time it is important to pass on and not merely take counting by adding one thing to another; indeed this is the least important aspect of counting and you should now teach the child as follows: “This is something which is ONE. Now you divide it like this, and you have something which is TWO. It is not two ONEs put together but the two come out of the ONE.” And so on with three and four. Thus you can awaken the thought that the ONE is really the comprehensive thing that contains within itself the TWO, the THREE, the FOUR, and if you learn to count in the way indicated in the diagram, 1, 2, 3, 4 and so on, then the child will have concepts that are living. He thereby comes to experience something of what it is to be inwardly permeated with the element of number.

In bygone ages our present conceptions of counting by placing one bean beside another or one bead beside another in the frame were quite unknown; in those days it was said that the unit was the largest, every two is only the half of it, and so on. So you come to understand the nature of counting

by actually looking at external objects. You should develop the child's thinking by means of external things which he can see, and keep him as far away as possible from abstract ideas.

The children can then gradually learn the numbers up to a certain point, first, let us say, up to twenty, then up to a hundred and so on. If you proceed on these lines you will be teaching the child to count in a living way. I should like to emphasise that this method of counting, real counting, should be presented to the child before he learns to do sums. The child ought to be familiar with this kind of counting before you go on to Arithmetic.

Arithmetic too must be approached out of life. The living thing is always a whole and must be presented as a whole first of all. You are doing wrong to a child if you always make him put together a whole out of its parts, and do not teach him to look first at the whole and then divide this whole into its parts; get him first to look at the whole and then divide it and split it up; this is the right path to a living conception.

Many things that the materialistic epoch has done with regard to the general culture of mankind pass unnoticed. Nowadays no one is scandalised but regards it rather as a matter of course to let children play with boxes of bricks, and build things out of the single blocks. This of itself leads them away from what is living. The child out of his very nature has no impulse to put together a whole out of parts. He has many other needs and impulses which are, admittedly, much less convenient. If you give him a watch for instance, he immediately has the desire to pull it to pieces, to break up the whole into its parts, which is actually far more in accordance with the nature of man—to see how the whole arises out of its component parts.

This is what must now be taken into account in our Arithmetic teaching. It has an influence on the whole of culture, as you will see from the following example.

In the conception of human thought up to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries very little emphasis was laid upon putting together a whole out of its parts; this arose later. The master-builder built much more from the idea of the whole (which he then split up into its parts) rather than starting with the single parts and making a building out of these. The latter procedure was really only introduced into civilisation later on. This conception then led to people thinking of every single thing as being put together out of the very smallest parts. Out of this arose the atomic theory in Physics, which really only comes from education. For atoms are really tiny little caricatures of demons, and our learned scholars would not speak about them as they do unless people had grown accustomed, in education, to putting everything together out of its parts. Thus it is that atomism has arisen.

We criticise atomism today, but criticism is really more or less superfluous because men cannot get free from what they have been used to thinking of wrongly for the last four or five centuries; they have become accustomed to go from the parts to the whole instead of letting their thoughts pass from the whole to the parts.

This is something we should particularly bear in mind in the teaching of Arithmetic. If you are walking towards a distant wood you first see the wood as a whole, and only when you come near it do you perceive that it is made up of single trees. This is just how you must proceed in Arithmetic. You never have in your purse, let us say, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 coins, but you have a heap of coins. You have all five together, which is a whole. This is what you have first of all. And when you cook pea soup you do not have 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or up to 3o or 4o peas, but you have one heap of peas, or with a basket of apples, for instance, there are not 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 apples, but one heap of apples in your basket. You have a whole. What does it matter to us to begin with, how many we have? We simply have a heap of apples which we are now bringing home (see diagram). There are, let us say, three children. We

will not now divide them so that each gets the same, for perhaps one child is small, another big. We put our hand into the basket and give the bigger child a bigger handful, the. smaller child a smaller handful; we divide our heap of apples into three parts.

Dividing or sharing out is in any case such a queer business! There was once a mother who had a large piece of bread. She said to her little boy, Henry: “Divide the bread, but you must divide it in a Christian way.” Then Henry said: “What does that mean, divide it in a Christian way?” “Well,” said his mother, “You must cut the bread into two pieces, one larger and one smaller; then you must give the larger piece to your sister Anna and keep the smaller one for yourself.” Whereupon Henry said, “Oh well, in that case let Anna divide it in a Christian way!”

Other conceptions must come to your aid here. We will do it like this, that we give this to one child, let us say {see lines in the drawing), and this heap to the second child, and this to the third. They have already learnt to count, and so that we get a clear idea of the whole thing we will first count the whole heap. There are eighteen apples. Now I have to count up what they each have. How many does the first child get? Five. How many does the second child get? Four. And the third? Nine. Thus I have started from the whole, from the heap of apples, and have divided it up into three parts.

Arithmetic is often taught by saying: “You have five, and here is five again and eight; count them together and you have eighteen.” Here you are going from the single thing to the whole, but this will give the child dead concepts. He will not gain living concepts by this method. Proceed from the whole, from the eighteen, and divide it up into the addenda; that is how to teach addition.

Thus in your teaching you must not start with the single addenda, but start with the sum, which is the whole, and divide it up into the single addenda. Then you can go on to show that it can be divided up differently, with different addenda, but the whole always remains the same. By taking addition in this way, not as is very often done by having first the addenda and then the sum, but by taking the sum first and then the addenda, you will arrive at conceptions that are living and mobile. You will also come to see that when it is only a question of a pure number the whole remains the same, but the single addenda can change. This peculiarity of number, that you can think of the addenda grouped in different ways, is very clearly brought out by this method.

From this you can then proceed to show the children that when you have something that is not itself a pure number but that contains number within it, as the human being for example, then you cannot divide it up in all these different ways. Take the human trunk for instance and what is attached to it, head, two arms and hands, two feet; you cannot now divide up the whole as you please; you cannot say: now I will cut out one foot like this, or the hand like this, and so on, for it has already been membered by nature in a definite way. When this is not the case, and it is simply a question of pure counting, then I can divide things up in different ways.

Such methods as these will make it possible for you to bring life and a kind of living mobility into your work. All pedantry will disappear and you will see that something comes into your teaching that the child badly needs: humour comes into the teaching, not in a childish but in a healthy sense. And humour must find its place in teaching.1At this. point Dr. Steiner turned to the translator and said: “Please be sure you translate the word ‘humour’ properly, for it is always misunderstood in connection with teaching!”

This then must be your method: always proceed from the whole. Supposing you had such an example as the following, taken from real life. A mother sent Mary to fetch some apples. Mary got twenty-five apples. The apple-woman wrote it down on a piece of paper. Mary comes home and brings only ten apples. The fact is before us, an actual fact of life, that Mary got twenty-five apples and only brought home ten. Mary is an honest little girl, and she really didn't eat a single apple on the way, and yet she only brought home ten. And now someone comes running in, an honest person, bringing all the apples that Mary dropped on the way. Now there arises the question: How many does he bring? We see him coming from a distance, but we want to know beforehand how many he is going to bring. Mary has come home with ten apples, and she got twenty-five, for there it is on the paper written down by the apple-woman, and now we want to know how many this person ought to be bringing, for we do not yet know if he is honest or not. What Mary brought was ten apples, and she got twenty-five, so she lost fifteen apples..

Now, as you see, the sum is done. The usual method is that something is given and you have to take away something else, and something is left. But in real life—you may easily convince yourselves of this—it happens much more often that you know what you originally had and you know what is left over, and you have to find out what was lost. Starting with the minuend and the subtrahend and working out the remainder is a dead process. But if you start with the minuend and the remainder and have to find the subtrahend, you will be doing subtraction in a living way. This is how you may bring life into your teaching.

You will see this if you think of the story of Mary and her mother and the person who brought the subtrahend; you will see that Mary lost the subtrahend from the minuend and that has to be justified by knowing how many apples the person you see coming along will have to bring. Here life, real life, comes into your subtraction. If you say, so much is left over, this only brings something dead into the child's soul. You must always be thinking of how you can bring life, not death, to the child in every detail of your teaching.

You can continue in this method. You can do multiplication by saying: “Here we have the whole, the product. How can we find out how many times something is contained in this product?” This thought has life in it. Just think how dead it is when you say: I will divide up this whole group of people, here are three, here are three more and so on, and now I ask: how many times three have we here? That is dead, there is no life in it.

If I proceed the other way round and take the whole and ask how often one group is contained within it, then I bring life into it. I can say to the children for instance: “Look, there is a certain number of you here in the class. Let us count. There are forty-five of you in the class. Now I am going to choose out five, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and put them over here.” Then I let them count up; how many times are these five contained within the forty-five? You see that here again I consider the whole and not the part. How many more of these groups of five can I make? Then I find out that there are eight more groups of five. Thus I do the thing the other way round and start with the whole, the product, and find out how often one factor is contained in it. Thereby I bring life into my arithmetical methods and above all I begin with something that the child can see before him. The chief point is that we must never, never separate thinking from visual experience, from what the child can see, for otherwise we shall bring intellectualism and abstractions to the child in early life and thereby ruin his whole being. He will become dried up and this will not only affect the soul life but the physical body also, causing desiccation and sclerosis. (We shall later have to speak of the education of spirit, soul and body as a unity.)

Here again much depends on our teaching Arithmetic in the way we have considered, so that in old age the human being is still mobile and skilful. You should teach the children to count from their own bodies as I have described, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, first with the fingers and then with the toes—yes indeed, it would be good to accustom the children actually to count up to twenty with their fingers and toes, not on a bead-frame. If you teach them thus then you will see that through this childlike kind of “meditation” you are bringing life into the body; for when you count on your fingers or toes you have to think about these fingers and toes, and this is then a meditation, a healthy kind of meditating on one's own body. If this is done a man will still be able to use his limbs skilfully in old age; the limbs can still function fully because they have learnt to count by way of the whole body. If a man only thinks with his head, rather than with his limbs and the rest of his organism, then later on the limbs lose their function and gout sets in.

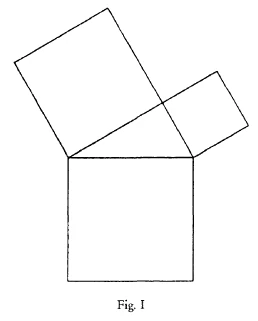

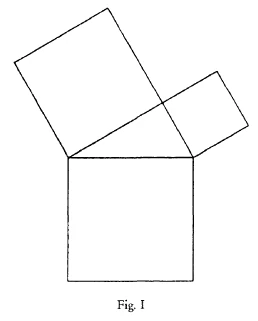

This principle, that everything in teaching and education must be worked out from what can be seen (but not from what are often called “object lessons” today)—this principle I should like to illustrate for you with an example, something which can actually play a very important part in teaching. I am referring to the Theorem of Pythagoras which as would-be teachers you must all be well acquainted with, and which you may even have already come to understand in a similar way; but we will speak of it again today. Now the Theorem of Pythagoras can be taken as a kind of goal in the teaching of Geometry. You can build up your Geometry lessons to reach their climax, their summit, in the Theorem of Pythagoras, which states that the square on the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides. It is a marvellous thing if we see it in the right light.

I once had to teach Geometry to an elderly lady because she loved it so much; she may have forgotten everything, I do not know, but she had probably not learnt much at her school, one of those schools for the “Education of Young Ladies.” At all events she knew no Geometry at all, so I began and made everything lead up to the Theorem of Pythagoras which the old lady found very striking. We are so used to it that it no longer strikes us so forcibly, but what we have to understand is simply that if I have a right-angled triangle here (see diagram) the area of the square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the other two areas, the two squares on the other two sides. So that if I am planting potatoes and put them at the same distance from each other everywhere, I shall plant the same number of potatoes in the two smaller fields together as in the larger one. This is something very remarkable, very striking, and when you look at it like this you cannot really see how it comes about.

It is just this fact of the wonder of it, that you cannot see how it comes about, that you must make use of to bring life into the more inward, soul quality of your teaching; you must build on the fact that here you have something that is not easily discernible; this must constantly be acknowledged. One might even say with regard to the Theorem of Pythagoras that you can believe it, but you always have to lose your belief in it again. You have to believe afresh every time that this square is equal to the sum of the other two squares.

Now of course all kinds of proofs can be found for this, but the proof ought to be given in a clear visual way. (Dr. Steiner then built up a proof for the Theorem of Pythagoras in detail based on the superposition of areas; he gave it in the conversational style used in this Lecture Course, and with the help of the blackboard and coloured chalks. For those who are interested a verbatim report of this proof, with diagrams, can be found in the Appendix on page 106.)

If you use this method of proof, i.e. laying one area over the other, you will discover something. If you cut it out instead of drawing it you will see that it is quite easy to understand. Nevertheless, if you think it over afterwards you will have forgotten it again. You must work it out afresh every time. You cannot easily hold it in your memory, and therefore you must rediscover it every time. That is a good thing, a very good thing. It is in keeping with the nature of the Theorem of Pythagoras. One must arrive at it afresh every time. One should always forget that one has understood it. This belongs to the remarkable quality of the Theorem of Pythagoras itself, and thereby you can bring life into it. You will soon see that if you make your pupils do it again and again, they have to ferret it out by degrees. They do not get it at once, they have to think it out each time. But this is in accordance with the inner living quality of the Theorem of Pythagoras. It is not good to give a proof that can be understood in a flat, dry kind of way; it is much better to forget it again constantly and work it out every time afresh. This is inherent in the very wonder of it, that the square on the hypotenuse is equal to the squares on the other two sides.

With children of eleven or twelve you can quite well take Geometry up to the point of explaining the Theorem of Pythagoras by this comparison of areas, and the children will enjoy it immensely when they have understood it. They will be enthusiastic about it, and will always be wanting to do it again, especially if you let them cut it out. There will perhaps be a few intellectual good-for-nothings who remember it quite well and can always do it again. But most of the children, being more reasonable, will cut it out wrong again and again and have to puzzle it out till they discover how it has to go. That is just the wonderful thing about the Theorem of Pythagoras, and we should not forsake this realm of wonder but should remain within it.

APPENDIX TO LECTURE 5

I. Proof for the Theorem of Pythagoras.

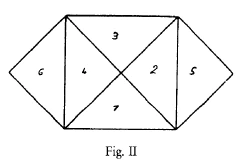

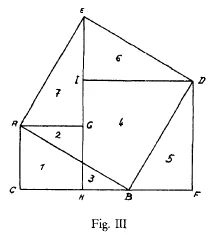

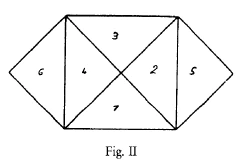

(As it has been impossible to reproduce the diagrams in colour, the forms which Dr. Steiner referred to by their colours have been indicated by letters or numbers.) It is quite easy to do this proof if the triangle is isosceles. If you have here a right-angled isosceles triangle (see diagram a.), then this is one side, this is the other and this the hypotenuse. This square (1, 2, 3, 4) is the square on the hypotenuse. The squares (2, 5) and (4, 6) are the squares on the other two sides.

Now if I plant potatoes evenly in these two fields (2, 5) and (4, 6), I shall get just as many as if I plant potatoes in

this field (1, 2, 3, 4). (1, 2, 3, 4) is the square on the hypotenuse, and the two fields (2, 5) and (4, 6) are the squares on the other two sides.

You can make the proof quite obvious by saying: the parts (2) and (4) of the two smaller squares fall into this space here (1, 2, 3, 4, the square on the hypotenuse); they are already within it. The part (5) exactly fits in to the space (3), and if you cut out the whole thing you can take the triangle (6) and apply it to (1), and you will see at once that it is the same. So that the proof is quite clear if you have a so-called right-angled isosceles triangle.

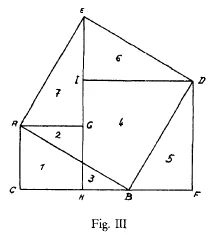

If however you have a triangle that is not isosceles, but has unequal sides (see diagram b.), you can do it as follows:

draw the triangle again ABC; then draw the square on the hypotenuse ABDE. Proceed as follows: draw the triangle ABC again over here, DBF. Then this triangle ABC or DBF (which is the same), can be put up there, AGE. Since you now have this triangle repeated over there, you can draw the square over one of the other sides, CAGH.

As you see, I can now also draw this triangle DEI congruent to BCA. Then the square DIHF is the square on the other side. Here I have both the square on the one side and the square on the other side. In the one case I use the side AG and in the other case the side DI. The two triangles AEG and DEI are congruent. Where is then the square on the hypotenuse? It is the square ABDE. Now I have to show from the figure itself that (1, 2) and (3, 4, 5) together make up (2, 4, 6, 7). Now I first take the square (1, 2); this has the triangle (2) in common with the square on the hypotenuse ABDE and section (4) of the square on the other side HIDF is also contained in ABDE. Thus I get this figure (2, 4) which you see drawn here and which is actually a piece of the square ABDE. This only leaves parts (1, 3 and 5) of the squares AGHC and DIHF to be fitted into the square on the hypotenuse ABDE. Now you can take part (5) and lay it over part (6), but you will still have this corner (1, 3) left over. If you cut this out you will discover that these two areas (1, 3) fit into this area (7). Of course it can be drawn more clearly but I think you will understand the process.

Fünfter Vortrag

Wenn man einem Kinde etwas beibringen will, muß man schon etwas von dem eigentlichen Wesen der Sache verstehen, um nicht sich im Unterrichte und in der Erziehung in Dingen zu bewegen, die dem Leben fernliegen. Alles, was dem Leben naheliegt, kann man verstehen. Man könnte auch sagen: Was man in Wirklichkeit versteht, muß dem Leben naheliegen. Die Abstraktionen liegen dem Leben nicht nahe.

Nun ist es heute so, daß der Lehrende, der Erziehende, von gewissen Dingen von vornherein nur Abstraktionen hat, daß er mit gewissen Dingen dem Leben nicht nahesteht. Das macht für die Erziehung und den Unterricht die allergrößten Schwierigkeiten. Bedenken Sie nur das Folgende: Sie wollen einmal darüber nachdenken, wie Sie dazu gekommen sind, Dinge zu zählen; was eigentlich damit getan ist, daß Sie zählen. Sie werden wahrscheinlich finden, daß der Faden Ihrer Untersuchungen irgendwo abreißt, daß Sie wohl Zählen gelernt haben, aber nicht recht eigentlich wissen, was Sie tun mit dem Zählen.

Nun werden allerlei Theorien für die Pädagogik ersonnen, wie man den Begriff der Zahl, wie man das Zählen einem Kinde beibringen soll, und gewöhnlich richtet man sich dann auch nach solchen Theorien. Wenn man damit auch äußerlich Erfolge erzielen kann, an den ganzen Menschen kommt man mit diesem Zählen oder mit solchen Dingen, die dem Leben fernliegen, nicht heran. Die neuere Zeit hat ja gerade dadurch bewiesen, wie sie in Abstraktionen lebt, daß sie solche Dinge wie die Rechenmaschine für den Unterricht erfunden hat. Im kaufmännischen Büro mögen die Leute Rechenmaschinen benützen, wie sie wollen, das geht uns jetzt nichts an, aber im Unterricht verhindert die Rechenmaschine, die sich ausschließlich an den Kopf wendet, von vorneherein, daß man in einer wesensgemäßen Weise mit der Zahl an das Kind herankommt.

Es handelt sich darum, daß man das Zählen wirklich aus dem Leben heraus gewinnt. Dabei wird vor allen Dingen wichtig sein, daß man von vornherein weiß, es kann sich gar nicht darum handeln, daß das Kind restlos alles versteht, was man ihm beibringt. Das Kind muß vieles auf Autorität aufnehmen, aber es muß es naturgemäß, sachgemäß aufnehmen.

Daher können Sie finden, daß das, was ich Ihnen nun über das Beibringen des Zählens sagen werde, vielleicht noch schwierig ist für das Kind. Aber das schadet nichts. Es ist außerordentlich bedeutsam, daß im Leben des Menschen solche Momente eintreten, wo man sich im 30., 40. Jahre sagt: Jetzt verstehe ich etwas, was ich damals im 8. oder 9. Jahre oder sogar noch früher in mich auf Autorität hin aufgenommen habe. - Das belebt. Wer dagegen all die Dinge betrachtet, die man heute als Anschauungsunterricht in den Unterricht einführen will, der kann tatsächlich ins Verzweifeln geraten, wie trivial die Dinge gemacht werden, um sie, wie man sagt, dem Verständnis des Kindes näherzubringen.

Denken Sie einmal, Sie nehmen selbst das kleinste Kind, das sich noch recht ungeschickt dabei benimmt, und Sie sagen ihm: Sieh einmal, du stehst jetzt da. Hier nehme ich ein Stück Holz. Da habe ich ein Messer. Ich zerschneide nun dieses Stück Holz. Kann ich das auch mit dir machen? - Da wird das Kind doch selber darauf kommen, daß ich das mit ihm nicht machen kann. Und nun kann ich dem Kinde sagen: Sieh einmal, wenn ich das Holz zerschneiden kann, dann ist das Holz also nicht so wie du, und du nicht so wie das Holz, denn dich kann ich nicht zerschneiden. Es ist also ein Unterschied zwischen dir und dem Holz. Der Unterschied besteht darinnen, daß du eine Einheit bist. Das Holz ist keine Einheit. Du bist eine Einheit. Dich kann ich nicht zerschneiden. Dasjenige, was du bist, deshalb, weil ich dich nicht zerschneiden kann, das nenne ich eine Einheit.

Nun, man wird jetzt allmählich dazu übergehen, dem Kinde ein Zeichen für diese Einheit beizubringen. Man macht einen Strich: I. Man bringt also dem Kinde bei, daß es eine Einheit ist, und man macht dafür diesen Strich.

Nun kann man abgehen von dem Holz und dem Vergleiche mit dem Kinde, und kann jetzt zu dem Kind sagen: Sieh einmal, da hast du deine rechte Hand, da hast du auch deine linke Hand. Und man wird dem Kinde beibringen können: Wenn du nur diese eine Hand hättest, dann könnte sich diese eine Hand überall hin bewegen, wie du selber. Aber wenn du so weitergehst, dann kannst du dir nicht begegnen, du kannst dich nicht angreifen. Wenn sich aber diese Hand und diese Hand bewegen, dann können sie sich angreifen, dann können sie zusammenkommen. Das ist etwas anderes, als wenn du bloß allein gehst. Weil du allein gehst, bist du eine Einheit. Aber die eine Hand kann der anderen Hand begegnen. Das ist nicht mehr eine Einheit, das ist eine Zweiheit. Siehst du, du bist einer, aber du hast zwei Hände. Das bezeichnest du dann so: II.

Auf diese Weise bringen Sie den Begriff der Einheit und der Zweiheit aus dem Kinde selbst heraus zustande.

Nun gehen Sie weiter, rufen ein zweites Kind heraus und sagen: Wenn ihr aber geht, könnt ihr euch auch begegnen, könnt ihr euch auch berühren. Ihr seid eine Zweiheit. Es kann aber noch einer dazukommen. Das kann bei den Händen nicht der Fall sein. So kann man übergehen beim Kinde zur Dreiheit: III.

Auf diese Weise kann man aus dem, was der Mensch selber ist, die Zahl ableiten: Man kommt vom Menschen zu der Zahl. Der Mensch ist etwas Lebendiges, nichts Abstraktes.

Und man kann übergehen und sagen: Sieh einmal, du hast noch irgendwo eine Zweiheit. - Man treibt das so lange, bis das Kind zu seinen beiden Beinen und Füßen kommt. Jetzt sagt man: Aber du hast schon des Nachbars Hund gesehen, ist der auch nur auf zwei Füßen? - Dann wird das Kind dazu kommen, in den vier Strichen IIII das sich Aufstützen von des Nachbars Hund kennenzulernen, und es wird so aus dem Leben heraus allmählich die Zahl aufbauen lernen.

Da ist es nun gut, wenn der Lehrer wieder überall offene Augen hat und alles mit Verständnis anschaut. So könnte ganz gut, weil man zuerst, wie es Ja auch natürlich ist, diese sogenannten römischen Zahlen anfängt zu schreiben - denn das ist dasjenige, was das Kind selbstverständlich gleich auffaßt - nun der Übergang gefunden werden von der Vier mit Hilfe der Hand zu der Fünf: V. Da wird man dem Kinde sagen: Das ist so, wenn du das (den Daumen) zurückhältst, so kannst du diese vier so benützen wie der Hund: IIII. Dann aber kommt noch der Daumen dazu, jetzt sind es fünf: V.

Ich stand einmal einem Lehrer gegenüber, der in der Erklärung der römischen Zahlen bis zu vier gekommen war, aber nicht darauf kommen konnte, warum es den Römern eingefallen ist, nun nicht fünf Striche nebeneinander zu machen, sondern dieses Zeichen V zu machen für die Fünf. Bis zu IIII konnte er es ganz gut bringen. Da sagte ich: Nun, machen wir es einmal so, legen wir die fünf Finger so auseinander, daß sie zwei Reihen bilden, und dann haben wir es: Da haben wir in der römischen Fünf die Hand drinnen. Das ist auch die Entstehung der römischen Fünf. Die Hand ist da drinnen.

In einem so kurzen Kurs kann man natürlich nur das Prinzip erklären. Aber auf diese Weise bekommt man die Möglichkeit, die Zahl selber unmittelbar aus dem Leben abzulesen. Und dann erst, wenn man in dieser Weise unmittelbar aus dem Leben die Zahl herausgewirkt hat, versucht man, das Zählen durch Anführen der Zahlen nacheinander durchzunehmen. Aber man versuche dieses so durchzunehmen, daß es den Kindern nicht gleichgültig bleibt. Ehe man ihm sagt: Jetzt sage mir einmal die Zahlen hintereinander auf: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 und so weiter, - gehe man zunächst vom Rhythmus aus. Sagen wir, wir gehen von 1 zu 2 = 1 2, 1 2, 1 2; wir lassen das Kind stärker auftreten bei dem 2, gehen zu 3 auch so ins Rhythmische hinüber = 1 2 3, 1 2 3. Auf diese Weise legen wir den Rhythmus in die Zahlenreihe hinein und bilden so auch die Fähigkeit beim Kiinde, die Dinge zusammenzufassen. Wir gelangen so wirklich in einer naturgemäßen Weise dazu, dem Kinde aus dem Wesen der Zahl heraus die Zahlen beizubringen.

Der Mensch glaubt gewöhnlich, er habe die Zahlen ausgedacht, indem er immer eins zum andern hinzugefügt hat. Das ist aber gar nicht wahr, der Kopf zählt überhaupt nicht. Man glaubt im gewöhnlichen Leben gar nicht, welch ein merkwürdiges, unnützes Organ für das Erdenleben dieser menschliche Kopf eigentlich ist. Er ist zur Schönheit da, gewiß, weil das Antlitz den anderen gefällt. Er hat noch mancherlei andere Tugenden, aber zu den geistigen Tätigkeiten ist er eigentlich gar nicht so stark da, denn dasjenige, was er geistig in sich hat, führt immer zurück in das frühere Erdenleben; er ist das umgestaltete frühere Erdenleben. Und einen richtigen Sinn hat es eigentlich nur dann für den Menschen, einen Kopf zu haben, wenn er etwas weiß von seinen früheren Erdenleben. Alles andere kommt gar nicht aus dem Kopf. Wir zählen nämlich in Wirklichkeit im Unterbewußten nach den Fingern. In Wirklichkeit zählen wir 1-10 an den Fingern und 11, 12, 13, 14 an den Zehen weiter. Das sieht man zwar nicht, aber man macht das so bis 20. Und dasjenige, was man im Körper auf diese Weise tut, das spiegelt sich im Kopfe nur ab. Der Kopf schaut nur bei allem zu. Der Kopf im Menschen ist wirklich nur ein Spiegelungsapparat von dem, was der Körper macht. Der Körper denkt, zählt; der Kopf ist nur ein Zuschauer.

Dieser Kopf hat eine merkwürdige Ähnlichkeit mit etwas anderem. Wenn Sie hier ein Auto haben (es wird gezeichnet) und Sie sitzen bequem darinnen, so tun Sie gar nichts, der Chauffeur da vorne muß sich plagen. Sie sitzen drinnen und werden durch die Welt gefahren. So ist es auch mit dem Kopf; der plagt sich nicht, der ist einfach auf Ihrem Körper, läßt sich ruhig durch die Welt tragen und schaut allem zu. Dasjenige, was getan wird im geistigen Leben, das wird alles vom Körper aus gemacht. Mathematisiert wird vom Körper aus, gedacht wird auch vom Körper aus, gefühlt wird auch vom Körper aus. - Die Rechenmaschine entspringt eben dem Irrtum, als ob der Mensch mit dem Kopf rechnete. Man bringt dann dem Kinde mit der Rechenmaschine die Rechnungen bei, das heißt, man strengt seinen Kopf an, und der Kopf strengt dann damit den Körper an, denn rechnen muß doch der Körper. Man berücksichtigt nicht, daß der Körper rechnen muß. Das ist wichtig. Deshalb ist es richtig, daß man das Kind mit den Fingern und auch mit den Zehen zählen läßt, wie es überhaupt ganz gut wäre, wenn man möglichste Geschicklichkeit bei den Kindern herausfordern würde. Es ist zum Beispiel nichts besser im Leben, als wenn man den Menschen im ganzen geschickt macht! Das kann man nicht durch Sport; der macht nicht eigentlich geschickt. Aber geschickt macht es zum Beispiel, wenn man den Menschen einen Griffel zwischen der großen und der nächsten Zehe halten läßt und ihn schreiben lernen läßt mit dem Fuß, Ziffern schreiben läßt mit dem Fuß. Das ist etwas, was durchaus Bedeutung haben kann, weil in Wahrheit der Mensch mit seinem ganzen Körper seelendurchdrungen, geistdurchdrungen ist. Der Kopf ist der sich anlehnende und nichtstuende Fahrende, währenddem der Körper überall der Chauffeur ist; der muß alles tun.

Und so muß man von den verschiedensten Seiten her versuchen, dasjenige, was das Kind als Zählen lernen soll, aufzubauen. So ist es wichtig, daß man, wenn man eine Zeitlang so gearbeitet hat, auch dazu kommt, das Zählen nicht bloß durch Zulegen von einem zum anderen - das ist sogar das allerwenigst wichtigste Zählen - hervorruft, sondern man bringt dem Kinde bei: Das ist die Einheit. Jetzt teilt man das ab (siehe Zeichnung): Das ist die Zweiheit. Es ist da nicht eine Ein! heit neben die andere gelegt zur Zweiheit, sondern da ist die Zweiheit aus der Einheit hervorgegangen. Das ist die Einheit (siehe oben), das ist nun die Dreiheit. Auf diese Weise kann man die Vorstellung hervorrufen, daß die Einheit eigentlich das Umfassende ist, dasjenige, was die Zweiheit, die Dreiheit, die Vierheit zusammenfaßt. Wenn man auf diese Weise zählen lernt (siehe Schema) 1, 2, 3, 4, und so weiter, werden die Begriffe des Kindes lebendig. Dadurch entsteht in dem Kinde ein innerliches Durchdringen des Zahlenmäßigen.

In gewissen Zeiten des Altertums hat man überhaupt unsere Begriffe des Zählens, wo immer nur eine Bohne neben die andere gelegt oder eine Kugel an der Rechenmaschine neben die andere gesetzt wird, gar nicht so gekannt, sondern man hat eben gesagt: Die Einheit ist das größte; jedes zwei ist nur die Hälfte davon und so weiter. Auf diese Weise kommen Sie in das Wesen des Zählens hinein, anschaulich, am Außending. Man soll das Denken des Kindes immer nur am Außending, am Anschaulichen entwickeln, die Abstraktion möglichst fernhalten.

Das Kind bekommt dann nach und nach die Möglichkeit, die Zahlenreihe zu haben bis zu einem gewissen Grade, meinetwillen zuerst bis 20, dann 100 und so weiter. Aber man gehe auf diese Weise vor, um dem Kinde das Zählen lebendig beizubringen. Ein Kind kann dann zählen. Wirklich zählen soll das Kind zuerst lernen - ich sage das ausdrücklich -, nicht gleich rechnen, sondern zählen. Das Kind soll zählen können, bevor man ans Rechnen geht.

Wenn man nun dem Kinde das Zählen nahegebracht hat, so wird es sich darum handeln, ans Rechnen heranzudringen. Auch das Rechnen muß aus dem Lebendigen herausgeholt werden. Das Lebendige ist immer ein Ganzes und als Ganzes zuerst gegeben. Man verübt Schlechtes an dem Menschen, wenn man ihn dazu veranlaßt, immer aus den Teilen ein Ganzes zusammenzusetzen, wenn man ihn nicht dazu erzieht, auf ein Ganzes hinzuschauen und dieses Ganze dann in Teile zu gliedern. Dadurch, daß man das Kind veranlaßt, auf ein Ganzes hinzuschauen, es zu gliedern und zu teilen, dadurch führt man das Kind an das Lebendige heran.

Man bemerkt ja vieles nicht, was die materialistische Zeit eigentlich mit Bezug auf die Menschheitskultur getrieben hat. Heute wird man gar keinen besonderen Anstoß daran nehmen, sondern es als etwas Selbstverständliches betrachten, Kinder mit dem Baukasten spielen zu lassen, einzelne Steinchen zu haben und aus denen so ein Gebäude zusammenzusetzen. Das ist von vornherein ein Wegführen des Kindes vom Lebendigen. Das Kind hat aus seiner Wesenheit heraus gar nicht das Bedürfnis, aus Teilen ein Ganzes zusammenzusetzen. Das Kind hat viele andere, allerdings unbequemere Bedürfnisse. Das Kind hat, wenn es nur einmal darauf kommt, gleich das Bedürfnis, wenn man ihm eine Uhr gibt, sie gleich zu zerteilen, das Ganze in die Teile zu zerlegen, und das entspricht viel mehr der Wesenheit des Menschen, nachzusehen, wie sich ein Ganzes in die Teile gliedert.

Das ist dasjenige, was nun auch beim Rechenunterricht berücksichtigt werden muß. Daß das auf die ganze Kultur einen Einfluß hat, mögen Sie aus folgendem Beispiel ersehen.

So bis ins 13., 14. Jahrhundert herein legte man gar keinen so großen Wert darauf, im menschlichen Denken ein Ganzes aus seinen Teilen zusammenzusetzen. Das kam erst später auf. Der Baumeister baute viel mehr aus der Idee des Ganzen heraus und gliederte in die Teile, als daß er aus Teilen ein Gebäude zusammengesetzt hätte. Das Zusammensetzen aus Teilen kam eigentlich erst später in die Menschheitszivilisation hinein. Und das hat dann dazu geführt, daß die Menschen überhaupt angefangen haben, alles aus kleinsten Teilen sich zusammengesetzt zu denken. Daraus kam die atomistische Theorie in der Physik. Die kommt nur aus der Erziehung. Unsere hohen Gelehrten würden gar nicht so sprechen von diesen winzigen kleinen Karikaturen von Dämonen - denn es sind Karikaturen von Dämonen -, von den Atomen, wenn man sich nicht in der Erziehung daran gewöhnt hätte, aus Teilen alles zusammenzusetzen. So ist der Atomismus gekommen. Wir kritisieren heute den Atomismus; aber eigentlich sind die Kritiken ziemlich überflüssig, weil die Menschen nicht loskommen von dem, was sie sich seit vier bis fünf Jahrhunderten angewöhnt haben verkehrt zu denken: Statt von dem Ganzen in die Teile hinein zu denken, von den Teilen auf das Ganze zu denken.

Das ist etwas, was man sich besonders beim Rechenunterricht sagen sollte. Wenn Sie von ferne auf einen Wald zugehen, haben Sie doch zuerst den Wald, und dann erst, wenn Sie nahe kommen, gliedern Sie den Wald in die einzelnen Bäume. So müssen Sie auch beim Rechnen vorgehen. Sie haben ja niemals in Ihrer Börse, sagen wir, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, sondern Sie haben einen Haufen Geldstücke. Sie haben die 5 zusammen. Das ist ein Ganzes. Das haben Sie zuerst. Sie haben auch gar nicht, wenn Sie sich eine Erbsensuppe kochen, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 bis 30, 40 Erbsen, sondern Sie haben einen Haufen. Sie haben auch nicht, wenn Sie ein Körbchen Äpfel haben, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 und so weiter Äpfel, sondern einen Haufen Äpfel in Ihrem Körbchen. Sie haben ein Ganzes. Was geht es uns zunächst an, wieviel wir haben, wir haben einen Haufen Äpfel (es wird gezeichnet). Jetzt kommen wir mit diesem Haufen Äpfel nach Hause. Drei Kinder sind da. Wir wollen zunächst gar nicht darauf ausgehen, die Teilung gleich so vorzunehmen, daß jedes das gleiche bekommt. Vielleicht ist das eine Kind klein, das andere groß. Wir greifen hinein, geben dem größeren Kind einen größeren Haufen, dem kleineren Kind einen kleineren Haufen; wir gliedern den Haufen Äpfel, den wir haben, in drei Teile.

Beim Teilen ist es ohnehin so eine merkwürdige Geschichte! Da hatte einmal eine Mutter ein großes Stück Brot und sagte zu dem einen Kind, das Heinrich hieß: Du mußt jetzt teilen, aber christlich teilen. - Da fragte der Heinrich: Was heißt denn das, christlich teilen? - Nun ja, sagte die Mutter, du mußt das Brot in ein kleineres und ein größeres Stück schneiden, das größere gibst du deiner Schwester Anna, du behältst das kleinere. - Darauf sagte Heinrich: Nein, dann soll nur die Anna christlich teilen!

Da muß man noch andere Begriffe zu Hilfe nehmen. Wir machen das so, daß wir zum Beispiel dem einen Kind das geben (siehe Abgrenzung bei der Zeichnung), dem zweiten Kind diesen Haufen und dem dritten Kind diesen Haufen. Damit wir es ordentlich überschauen können, zählen wir zunächst den ganzen Haufen, denn zählen kann das Kind schon. Es sind 18 Äpfel. Jetzt habe ich es zu zählen. Wieviel hat das erste Kind? 5. Wieviel hat das zweite Kind? 5. Wieviel hat das dritte Kind? 8.

Somit bin ich vom Ganzen ausgegangen, vom ganzen Haufen Äpfel, und habe ihn in drei Teile aufgeteilt.

Sehr häufig macht man es im Unterricht so, daß man sagt: Du hast 5 und noch einmal 5 und 8; die zählst du zusammen, dann gibt das 18. Da gehen Sie vom Einzelnen aus und kommen zum Ganzen. Aber das gibt dem Kind tote Begriffe, keine lebendigen Begriffe. Gehen Sie vom Ganzen aus, von den 18, und teilen Sie es auf in die Summanden, so bekommen Sie die Addition.

Unterrichten Sie also nicht so, daß Sie ausgehen von dem einzelnen Addenden oder Summanden, sondern gehen Sie von der Summe aus - die ist das Ganze - und gliedern Sie sie in die einzelnen Addenden. Dann können Sie dazu kommen, nun zu sagen: Aber ich kann jetzt auch anders aufteilen. Ich kann so teilen ... ich habe nun andere Addenden, das Ganze bleibt immer gleich. Dadurch, daß Sie die Addition nicht so nehmen, wie man sie sehr häufig nimmt, indem man zuerst die Addenden hat und dann die Summe, sondern zuerst die Summe gibt und dann die Addenden, kommen Sie zu ganz lebendigen, beweglichen Begriffen. Sie kommen auch darauf, daß da, wo es nur auf die Zahl ankommt, das Ganze eben etwas Gleichbleibendes ist; die einzelnen Summanden, Addenden, können sich ändern. Dieses Eigentümliche der Zahl, daß man sich die Addenden in verschiedener Art gruppiert denken kann, das kommt dabei sehr schön heraus.

Dann können Sie übergehen und sagen: Wenn aber etwas nicht nur Zahl ist, sondern die Zahl in sich hat, wie der Mensch, dann kann man nicht in verschiedener Weise teilen. So zum Beispiel wenn Sie den menschlichen Rumpf nehmen und dasjenige, was daran hängt, Kopf, Arme und Füße, da können Sie nicht in beliebiger Weise das Ganze aufteilen, da können Sie nicht sagen: Ich schneide den einen Fuß so heraus, die Hand so heraus und so weiter, sondern das ist in bestimmter Weise schon von der Natur aus gegliedert.

Wo es bloß auf das Zählen ankommt, da ist nicht von der Natur aus gegliedert, da kann ich in verschiedener Weise aufteilen.

Das ist dasjenige, wodurch Sie überhaupt die Möglichkeit bekommen, Leben und lebendiges Fließen in den Unterricht hineinzubringen. Alle Pedanterie fällt heraus aus dem Unterricht, und Sie werden sehen, es kommt etwas in den Unterricht hinein, was das Kind außerordentlich gut braucht: Es kommt in gesundem Sinne, nicht in kindischem Sinne, Humor in den Unterricht hinein. Und Humor muß in den Unterricht hineinkommen.

Übersetzen Sie das Wort «Humor» gut; das wird immer im Unterricht mißverstanden!

So müssen Sie überhaupt im Unterricht vorgehen: Überall von dem Ganzen ausgehen. Nehmen Sie einmal an, Sie wollen, ganz aus dem Leben heraus, folgendes machen. Die Mutter hat das Mariechen geschickt, Äpfel zu holen. Das Mariechen hat 25 Äpfel bekommen. Das hat die Kaufmannsfrau auf einen Zettel aufgeschrieben. Das Mariechen kommt nach Hause und bringt nur 10 Äpfel. Die Tatsache liegt vor, die ist aus dem Leben: Das Mariechen hat 25 Äpfel bekommen und hat nur 10 nach Hause gebracht. Das Mariechen ist ein ehrliches Mariechen, hat wirklich keinen einzigen Apfel auf dem Wege aufgegessen, hat aber doch nur 10 Äpfel nach Hause gebracht. Jetzt kommt jemand nachgelaufen, der auch ehrlich ist, und bringt alle die Äpfel nach, die das Mariechen auf dem Weg verloren hat. Jetzt wird die Frage entstehen: Wieviel bringt der nach? Man sieht ihn erst von ferne kommen. Jetzt will man vorher wissen, wieviele er nachbringt. Nun, das Mariechen ist angekommen, 10 Äpfel hat es gebracht, 25 hatte es bekommen, das sieht man auf dem Zettel, auf dem die Frau es aufgeschrieben hat. Es hat also 15 Äpfel verloren.

Sehen Sie, jetzt haben Sie die Rechnung gemacht. Gewöhnlich macht man es so: Etwas ist gegeben, man soll etwas abziehen, und dann bleibt etwas übrig. Aber im Leben - Sie werden sich davon überzeugen - kommt es viel häufiger vor, daß man dasjenige, was man ursprünglich bekommen hat, und dasjenige, was übriggeblieben ist, weiß, und man muß dasjenige, was verlorengegangen ist, aufsuchen. Man soll also die Subtraktion, damit man die Sache lebendig treibt, so machen, daß man vom Minuend und vom Rest ausgeht, und den Subtrahend sucht; nicht vom Minuend und Subtrahend ausgehen und den Rest suchen. Das ist tot. Lebendig ist es, vom Minuend und vom Rest auszugehen und den Subtrahenden zu suchen. Dadurch bekommen Sie Leben in den Unterricht hinein.

Sie werden das schon sehen, wenn Sie die Sache von der Mutter und dem Mariechen ins Auge fassen und den, der den Subtrahenden bringt. Das Mariechen hat vom Minuend den Subtrahend verloren, und das will man so rechtfertigen, daß man von dem, der da nachkommt, den man herankommen sieht, wissen will, wieviel er bringen muß. Da kommt in die ganze Subtraktion Leben, wirkliches Leben hinein. Wenn man nur danach fragt: Wieviel bleibt übrig - bringt das nur Totes in die Seele des Kindes hinein. Sie müssen immer darauf bedacht sein, überall das Lebendige, nicht das Tote in das Kind hineinzubringen.

Und so können Sie dann weitergehen. Sie können die Multiplikation so treiben, daß Sie sagen: Das Ganze, das Produkt ist vorhanden; wie kann man finden, wievielmal irgend etwas in diesem Produkt drinnensteckt? Sehen Sie, da kommen Sie auf Lebendiges. Denken Sie einmal, wie tot es ist, wenn Sie sagen: Ich teile mir diese ganze Gruppe von Menschen ab, da sind drei, da sind noch einmal drei und so weiter, und ich frage jetzt: wievielmal drei sind da? - Das ist tot, da ist kein Leben drinnen.

Wenn ich umgekehrt vorgehe und das Ganze nehme und frage, wie oft irgendeine Gruppe drinnen stecke, dann kann ich Leben hineinbringen. Ich kann zum Beispiel zu den Kindern so sagen: Seht, ihr seid hier in der Klasse eine gewisse Zahl. Zählen wir es ab. Ihr seid 45. Jetzt suche ich mir 5 heraus, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, die stelle ich da her. Nun lasse ich abzählen, wievielmal sind diese 5 da drinnen in diesen 45? Sehen Sie, da gehe ich wieder aufs Ganze, nicht in den Teil. Wieviel solcher Fünfer-Gruppen kann ich noch machen? Da komme ich darauf, es sind noch acht Fünfer-Gruppen da drinnen. Also ich mache die Sache umgekehrt, gehe vom Ganzen aus, vom Produkt, und suche, wie oft ein Faktor da drinnen steckt. Dadurch belebe ich mir die Rechnungsarten und gehe vor allen Dingen vom Anschaulichen aus. Und darauf kommt es an, daß wir das Denken nie, nie, nie loslösen von dem Anschaulichen, sonst kommt an das Kind früh der Intellektualismus, die Abstraktion heran, und wir verderben das ganze Kind. Wir machen es trocken, und außerdem züchten wir in ihm - wir werden noch sprechen von der geistig-seelisch-physischen Erziehung -, wir züchten in ihm die Austrocknung auch des physischen Leibes, die Sklerose.

Wiederum hängt viel davon ab, daß wir so rechnen lehren, wie es hier beobachtet worden ist, damit der Mensch im Alter noch beweglich bleibt, noch geschickt ist. Wenn Sie am menschlichen Körper, so wie ich es beschrieben habe, zählen lehren, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 und dann weiter mit den Zehen - ja es wäre schon ganz gut, wenn man die Kinder gewöhnen würde, bis 20 wirklich mit Fingern und Zehen zu zählen, nicht mit der Rechenmaschine -, wenn Sie das die Kinder lehren, dann werden Sie sehen, durch dieses kindliche Meditieren - denn wenn man an den Fingern zählt, wenn man mit den Zehen zählt, so muß man auch an die Finger und Zehen denken, das ist ein Meditieren über den eigenen Körper, und zwar ein gesundes Meditieren -, da bringt man Leben hinein in den Körper. Man ist dann im Alter mit den Gliedern noch geschickt; sie behaupten sich, weil sie am ganzen Organismus das Zählen gelernt haben. Wenn man nur mit dem Kopfe denkt, nicht mit den Gliedern und dem übrigen Organismus denkt, dann können sie sich später auch nicht behaupten, und man kriegt die Gicht.

Wie man aus dem Anschaulichen heraus, nicht aus dem, was man heute oftmals «Anschauungsunterricht» nennt, alles in Erziehung und Unterricht besorgen muß, das möchte ich Ihnen nun an einem bestimmten Fall zeigen, der ja tatsächlich im Unterricht eine ganz besondere Rolle spielen kann. Es ist der Fall des pythagoreischen Lehrsatzes, den Sie ja wohl alle kennen, wenn Sie unterrichten werden, den Sie vielleicht schon in einer ähnlichen Weise durchschaut haben, aber wir wollen ihn heute doch noch besprechen. Sehen Sie, der pythagoreische Lehrsatz bedeutet etwas, was man sich tatsächlich im Unterrichte so als ein Ziel hinstellen kann für die Geometrie. Man kann schon die Geometrie so aufbauen, daß man sagt: Man will alles so gestalten, daß sie gipfelt in dem pythagoreischen Lehrsatz, daß das Quadrat der Hypotenuse eines rechtwinkligen Dreiecks gleich ist der Summe der beiden Kathetenquadrate. Es ist etwas ganz Grandioses, wenn man das so recht ins Auge faßt.

Ich habe einmal einer Dame, die dazumal schon älter war, weil sie das so liebte, Geometrie beibringen sollen. Ich weiß nicht, ob sie alles vergessen hatte - aber vermutlich hatte sie nicht viel gelernt gehabt in den Mädchenerziehungsinstituten, in denen man so als Mädchen erzogen wird -, jedenfalls wußte sie nichts von Geometrie. Ich fing nun an und gipfelte das Ganze bis zum pythagoreischen Lehrsatz hin. Nun hatte der pythagoreische Lehrsatz für die Dame in der Tat etwas außerordentlich Frappierendes. Man ist nur gewöhnt an dieses Frappierende. Aber nicht wahr, man soll einfach das verstehen, daß, wenn ich hier ein rechtwinkliges Dreieck habe (es wird gezeichnet), die Fläche, die als Quadrat über der Hypotenuse errichtet wird, gleich ist der Summe dieser beiden Quadratflächen über den Katheten (Fig. I). Daß, wenn ich also Kartoffeln pflanze, und sie überall in den gleichen Entfernungen anordne, ich, wenn ich dieses Feld und dieses zusammen mit Kartoffeln bepflanze, genau soviel Kartoffeln anpflanzen werde, wie hier auf diesem Felde. Das ist etwas Frappierendes, etwas ganz Frappierendes, und wenn man es so ansieht, kann man es nicht eigentlich durchschauen.

Und gerade das, daß man es nicht durchschauen kann, daß es etwas so Wunderbares ist, sollte man zum inneren Beleben des Seelischen im Unterricht benutzen; man sollte darauf bauen, daß man da etwas nicht so furchtbar Durchsichtiges hat, das man doch immer wieder zugeben muß. Man möchte sagen, beim pythagoreischen Lehrsatz ist es so: Man kann an ihn glauben, aber man muß den Glauben immer gleich wieder verlieren. Man muß immer von neuem wieder daran glauben, daß das Hypotenusenquadrat gleich ist der Summe der beiden Kathetenquadrate.

Nun kann man ja allerlei Beweise finden, und der Beweis sollte eigentlich ganz anschaulich geliefert werden. Er ist leicht zu liefern, solange das Dreieck gleichschenklig ist. Wenn Sie hier ein gleichschenklig-rechtwinkliges Dreieck haben (es wird gezeichnet, Fig. II), so ist dieses hier die eine Kathete, dies ist die andere Kathete, das ist die Hypotenuse. Das, was ich jetzt orange zeichne (1, 2, 3, 4), ist das Quadrat über der Hypotenuse. Das, was ich blau zeichne, sind die Quadrate über den beiden Katheten (2, 5; 4, 6).

Nun ist es wiederum so, wenn ich in der richtigen Weise hier über diesen beiden blauen Feldern (2, 5; 4, 6) Kartoffeln anpflanze, bekomme ich gleich viel, wie wenn ich in dem orangen Feld (1, 2, 3, 4) Kartoffeln anpflanze. Das orange Feld ist das Quadrat über der Hypotenuse, die beiden blauen Felder (2, 5; 4, 6) sind die Quadrate über den beiden Katheten.

Nun können Sie ja den Beweis einfach machen, indem Sie sagen: Die zwei Stücke (2, 4) von den beiden blauen Quadraten, die fallen da (ins Hypotenusenquadrat) herein, die sind schon drinnen. Das da (5) können Sie hier heraufsetzen (auf 3). Wenn Sie sich das Ganze ausschneiden, können Sie das Stück (6) hier darauflegen (auf 1), und Sie haben es gleich. Also, da ist die Sache ganz durchsichtig, wenn man ein sogenanntes rechtwinklig-gleichschenkliges Dreieck hat. Aber hat man nicht ein rechtwinklig-gleichschenkliges Dreieck, sondern eines von verschiedenen Seiten (wie Fig. ID), da kann man das Folgende machen: Zeichnen Sie sich dieses Dreieck noch einmal heraus (Fig. II: ABC). Zeichnen Sie jetzt das Quadrat über der Hypotenuse ABDE. Nun können Sie in folgender Weise zeichnen: Sie können das Dreieck ABC, das Sie hier haben, hier daran zeichnen: BDF. Dann können Sie dieses Dreieck ABC, respektive dieses BDF, was dasselbe ist, noch einmal hierher zeichnen: AEG. Dadurch, daß Sie dieses Dreieck hier noch einmal haben, können Sie sich das Quadrat über dieser einen Kathete so herzeichnen (rot) CAGH. Jetzt ist das, was ich rot gezeichnet habe, das Quadrat über der einen Kathete (CAGH).

Ich kann nun auch, wie Sie sehen, das Dreieck hierher zeichnen: DEI. Hier habe ich es auch. Dann habe ich in dem, was ich hier jetzt grün zeichne, das Quadrat über der anderen Kathete: DIHF; dann habe ich da zwei, das Quadrat über der einen Kathete, das Quadrat über der anderen Kathete. Ich benutze nur bei dem einen diese Kathete AG, bei dem anderen diese Kathete DI. Die Dreiecke sind da (AEG) und da (DEI); aber gleich (das heißt kongruent). Wo habe ich das Quadrat über der Hypotenuse? Das will ich nun violett hineinzeichnen, damit wir es gut unterscheiden können: ABDE. Das Quadrat über der Hypotenuse habe ich hier. Jetzt soll ich an der Figur selber zeigen, daß rot (1, 2) und grün (3, 4, 5) zusammen violett (2, 4, 6, 7) gibt.

Nun werden Sie ja leicht einsehen können: Ich nehme dieses rote Quadrat (1, 2) hier zuerst; dasjenige, was die beiden Quadrate gemeinschaftlich haben (2), das fällt ja übereinander. Nun kommt da noch das Stück vom grünen Quadrat (4) herein. So habe ich also diese Figur (2, 4), die Sie da gezeichnet sehen und die nichts anderes ist als ein Stück von dem violetten Quadrat ABDE, richtig ein Stück von dem violetten Quadrat. Dieses Stück von dem violetten Quadrat ABDE enthält dieses Stück von dem roten Quadrat (2); bleibt davon nur noch der Zipfel hier übrig (1); den enthält es noch nicht. Aber außerdem enthält diese Figur diesen Zipfel von dem grünen Quadrat (4). Jetzt muß ich nur noch darauf kommen, das unterzubringen, was mir da übriggeblieben ist (1, 3, 5).

Nun müssen Sie einmal sehen: Da ist Ihnen ein Stückchen vom roten Quadrat übriggeblieben (1), da ein Stückchen vom grünen Quadrat (3), und da ist Ihnen dieses ganze Dreieck (5) übriggeblieben, das auch zum grünen Quadrat DIHF gehört. Jetzt nehmen Sie das, was Sie hier haben, was Ihnen da noch übriggeblieben ist, und setzen es da an; dasjenige, was Ihnen hier noch übriggeblieben ist (5), nehmen Sie und setzen es da an (6). Jetzt haben Sie auch noch die Zipfel da (1, 3). Wenn Sie das ausschneiden, kommen Sie richtig darauf, daß diese beiden Flächen (1, 3) in diese Fläche (7) hineingefallen sind. Es kann natürlich noch deutlicher gezeichnet werden, aber ich denke, Sie werden die Sache durchschauen. Es handelt sich jetzt nur noch darum, daß es sich durch die Sprache noch näher mitteilt. Auf diese Weise haben Sie einfach durch das Flächen-Übereinanderlegen gezeigt, daß der pythagoreische Lehrsatz richtig ist. Wenn Sie gerade diese Art des Übereinanderlegens nehmen, so werden Sie etwas finden. Sie werden zwar sehen, wenn Sie die Sache ausschneiden, statt daß Sie es aufzeichnen, daß sie sehr leicht überschaubar ist; trotzdem, wenn Sie später darüber nachdenken, wird es Ihnen wieder entfallen. Sie müssen es immer wieder von neuem suchen. Sie können es sich nicht ganz gut im Gedächtnis merken, daher muß man es immer wieder aufs neue suchen. Und das ist gut. Das ist nämlich ganz gut. Das entspricht dem pythagoreischen Lehrsatz. Man soll immer wieder von neuem darauf kommen. Daß man ihn einsieht, soll man immer wieder vergessen. Das entspricht dem Frappierenden, was der pythagoreische Lehrsatz hat. Dadurch bekommen Sie das Lebendige in die Sache hinein. Sie werden schon sehen, wenn Sie dieses von den Schülern wieder und wieder machen lassen, die müssen es herausdrucksen. Sie kommen nicht gleich wieder darauf, sie müssen jedesmal nachdenken. Das entspricht aber dem InnerlichLebendigen des pythagoreischen Lehrsatzes. Es ist gar nicht gut, wenn man den pythagoreischen Lehrsatz so beweist, daß er platt philiströs einzusehen ist; es ist viel besser, daß man ihn immer wieder vergißt und immer wieder von neuem suchen muß. Das entspricht dem Frappierenden, daß es doch etwas Sonderbares ist, daß das Hypotenusenquadrat gleich ist der Summe der beiden Kathetenquadrate.

Nun können Sie ganz gut mit elf- oder zwölfjährigen Kindern die Geometrie so weit bringen, daß Sie den pythagoreischen Lehrsatz in einem solchen Flächenvergleich erklären; die Kinder werden eine ungeheure Freude haben, wenn sie das eingesehen haben, und sie bekommen Eifer. Das hat sie gefreut. Jetzt wollen sie es immer wieder machen, besonders, wenn man sie es ausschneiden läßt. Es wird nur ein paar intellektualistische Taugenichtse geben, die sich das ganz gut merken, die es immer wieder zustande bringen. Die meisten, vernünftigeren Kinder, werden immer wieder sich verschneiden und daran herumdrucksen, bis sie herausbekommen, wie es sein muß. Das entspricht aber dem Wunderbaren des pythagoreischen Lehrsatzes, und man soll nicht aus diesem Wunderbaren herauskommen, sondern drinnen stehenbleiben.

Fifth Lecture

If you want to teach a child something, you have to understand something of the actual nature of the subject, so that you do not stray into teaching and educating them about things that are far removed from life. Everything that is close to life can be understood. One could also say: what one understands in reality must be close to life. Abstractions are not close to life.

Nowadays, teachers and educators have only abstractions of certain things from the outset, meaning that they are not close to life in certain respects. This causes the greatest difficulties for education and teaching. Just consider the following: think about how you came to count things; what actually happens when you count. You will probably find that the thread of your investigations breaks off somewhere, that you have learned to count, but do not really know what you are doing when you count.

Now all kinds of theories are being devised for education, how to teach a child the concept of numbers, how to teach counting, and usually such theories are then followed. Even if this may lead to outward success, it is not possible to reach the whole person with this counting or with such things that are far removed from life. Recent times have proven how much they live in abstractions by inventing things like the calculating machine for teaching. People may use calculators in commercial offices as they please; that is none of our concern. But in the classroom, the calculator, which appeals exclusively to the head, prevents us from approaching the child in a way that is appropriate to its nature.

The point is that counting is really learned from life. Above all, it is important to know from the outset that it is impossible for the child to understand everything that is taught to them. The child must accept many things on authority, but they must accept them naturally and appropriately.

Therefore, you may find that what I am about to tell you about teaching counting is perhaps still difficult for the child. But that does not matter. It is extremely important that there are moments in a person's life when, at the age of 30 or 40, they say to themselves: Now I understand something that I absorbed on authority when I was 8 or 9, or even earlier. That is invigorating. On the other hand, anyone who considers all the things that are being introduced into teaching today as visual aids may indeed despair at how trivial things are being made in order to bring them closer to the child's understanding, as they say.

Just imagine, you take even the smallest child, who is still quite clumsy, and you say to him: Look, you are standing there now. Here I have a piece of wood. Here I have a knife. I am now going to cut this piece of wood. Can I do the same with you? The child will realize for himself that I cannot do that with him. And now I can say to the child: Look, if I can cut the wood, then the wood is not like you, and you are not like the wood, because I cannot cut you. So there is a difference between you and the wood. The difference is that you are a unity. The wood is not a unity. You are a unity. I cannot cut you. What you are, because I cannot cut you up, I call a unity.

Now, we will gradually move on to teaching the child a sign for this unity. We make a line: I. So we teach the child that it is a unity, and we make this line for it.

Now we can move away from the wood and the comparison with the child, and say to the child: Look, you have your right hand, and you also have your left hand. And we can teach the child: If you only had this one hand, then this one hand could move everywhere, just like you yourself. But if you continue like this, you cannot meet yourself, you cannot touch yourself. But when this hand and this hand move, they can touch each other, they can come together. This is different from when you walk alone. Because you walk alone, you are a unity. But one hand can meet the other hand. This is no longer a unity, it is a duality. You see, you are one, but you have two hands. You then describe this as: II.

In this way, you bring out the concept of unity and duality from the child itself.

Now you go on, call out a second child and say: But when you walk, you can also meet each other, you can also touch each other. You are a duality. But another one can join you. That cannot be the case with hands. In this way, you can move on to the trinity with the child: III.

In this way, you can derive the number from what the human being is: you come from the human being to the number. The human being is something living, not something abstract.

And you can move on and say: Look, you still have a duality somewhere. You continue this until the child comes to its two legs and feet. Now you say: But you have already seen the neighbor's dog, does it also stand on only two feet? Then the child will come to recognize the neighbor's dog standing on its two legs in the four strokes IIII, and will gradually learn to construct the number from life itself.

Now it is good if the teacher again has open eyes everywhere and looks at everything with understanding. It could be quite good, because first, as is natural, one begins to write these so-called Roman numerals – for that is what the child naturally understands right away – now the transition can be made from the four with the help of the hand to the five: V. The child will be told: this is how it is, if you hold back (your thumb), you can use these four like the dog: IIII. But then the thumb is added, and now there are five: V.

I once stood opposite a teacher who had come to four in his explanation of Roman numerals, but couldn't figure out why the Romans had decided not to make five lines next to each other, but to make this sign V for five. He was able to explain it quite well up to IIII. So I said: Well, let's do it this way, let's spread our five fingers out so that they form two rows, and then we have it: there we have the Roman five in our hand. That is also the origin of the Roman five. The hand is in there.

In such a short course, of course, one can only explain the principle. But in this way, one has the opportunity to read the number directly from life itself. And only then, when one has derived the number directly from life in this way, does one try to go through counting by listing the numbers one after the other. But try to do this in such a way that the children do not remain indifferent. Before you say to them, “Now tell me the numbers one after the other: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and so on,” start with the rhythm. Let's say we go from 1 to 2 = 1 2, 1 2, 1 2; we let the child emphasize the 2 more strongly, then move on to 3 in the same rhythmic way = 1 2 3, 1 2 3. In this way, we put rhythm into the number sequence and thus also develop the child's ability to summarize things. In this way, we really manage to teach the child numbers in a natural way, based on the essence of numbers.

People usually believe that they invented numbers by adding one to the other. But that is not true at all; the head does not count at all. In everyday life, we do not realize what a strange, useless organ the human head actually is for earthly life. It is there for beauty, of course, because the face pleases others. It has many other virtues, but it is not really that strong when it comes to intellectual activities, because what it has intellectually within itself always leads back to its previous earthly life; it is the transformed previous earthly life. And it only really makes sense for humans to have a head if they know something about their previous earthly lives. Everything else does not come from the head at all. In reality, we count on our fingers in our subconscious. In reality, we count 1-10 on our fingers and 11, 12, 13, 14 on our toes. You can't see it, but you do this up to 20. And what you do in your body in this way is only reflected in your head. The head just watches everything. The head in humans is really only a mirror of what the body does. The body thinks, counts; the head is only a spectator.This head bears a strange resemblance to something else. If you have a car here (it is drawn) and you sit comfortably inside it, you do nothing at all; the chauffeur up front has to do all the work. You sit inside and are driven through the world. It is the same with the head; it does not struggle, it is simply on your body, lets itself be carried quietly through the world and watches everything. Everything that is done in intellectual life is done from the body. Mathematics is done from the body, thinking is also done from the body, feeling is also done from the body. The calculating machine arises from the misconception that humans calculate with their heads. Children are then taught arithmetic with the calculating machine, which means they strain their heads, and their heads then strain their bodies, because it is the body that has to do the calculating. No consideration is given to the fact that the body has to do the calculations. This is important. That is why it is right to let children count with their fingers and toes, just as it would be good to encourage children to develop as much dexterity as possible. For example, there is nothing better in life than making people dexterous as a whole! This cannot be achieved through sport; sport does not actually make people dexterous. But it does make them dexterous, for example, if you let them hold a stylus between their big toe and the next toe and let them learn to write with their foot, writing numbers with their feet. This is something that can be very important, because in truth, the human being is imbued with soul and spirit throughout their entire body. The head is the leaning, idle passenger, while the body is the driver everywhere; it has to do everything.

And so one must try from various angles to build up what the child should learn as counting. It is important, after working in this way for a while, not only to teach counting by adding one to another – which is actually the least important form of counting – but also to teach the child: This is the unity. Now you divide it (see drawing): this is the duality. It is not one unity placed next to another to form a duality, but rather the duality has emerged from the unity. This is the unity (see above), this is now the trinity. In this way, one can evoke the idea that unity is actually the comprehensive, that which encompasses duality, triality, and quadruality. When one learns to count in this way (see diagram) 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on, the child's concepts come alive. This creates an inner penetration of the numerical in the child.

In certain periods of antiquity, our concepts of counting, where one bean is placed next to another or one ball is placed next to another on the abacus, were not known at all. Instead, it was simply said: The unit is the largest; each two is only half of it, and so on. In this way, you get into the essence of counting, vividly, on the outside. One should always develop the child's thinking only on the outside, on the vivid, keeping abstraction as far away as possible.

The child is then gradually given the opportunity to learn the number sequence to a certain extent, for my part first up to 20, then 100, and so on. But one should proceed in this way in order to teach the child to count in a lively manner. A child can then count. The child should first learn to count – I say this explicitly – not to calculate, but to count. The child should be able to count before moving on to arithmetic.