An Occult Physiology

GA 128

20 March 1911, Prague

1. The Being of Man

This lecture-cycle deals with a subject which concerns Man very closely, namely, the exact nature and life of Man himself. Although so close to man, because it concerns himself; the subject is a difficult one to approach. For if we turn our attention to the challenge ”Know thyself!”, a challenge that has forced itself upon man through all the ages, as we may say, from mystic, occult heights, we see at once that a real, true self-knowledge is very hard of attainment. This applies not only to individual, personal self-knowledge, but above all to knowledge of the human being as such. Indeed it is precisely because man is so far from knowing his own being and has such a long way to go in order to know himself, that the subject we are about to discuss in the course of these few days will be in a certain respect something alien to us, something for which much preparation is necessary. Moreover it is not without reason that I myself have only reached the point where I can at last speak upon this theme as the result of mature reflection covering a long period of time. For it is a theme which cannot be approached with any prospect of arriving at a true and honest observation unless a certain attitude, often left out of account in ordinary scientific observation, be adopted. This attitude is one of reverence in the presence of the essential nature and Being of Man. It is, then, of vital importance that we maintain this attitude as a fundamental condition underlying the following reflections.

How can one truly maintain this reverence? In no other way, than by first disregarding what he appears to be in everyday life, whether it be oneself or another is of no consequence, and then by uplifting ourselves to the conception: Man, with all that he has evolved into, is not here for his own sake; he is here as revelation of the Divine Spirit, of the whole World. He is a revelation of the Godhead of the World! And, when a man speaks of aspiring after self-knowledge, of aspiring to become ever more and more perfect, in the spiritual-scientific sense which has just been indicated, this should not be due to the fact that he desires merely from curiosity, or from a mere craving or knowledge, to know what man is; but rather that he feels it to be his duty to fashion ever more and more perfectly this representation, this revelation, of the World Spirit through Man, so that he may find some meaning in the words, “to remain unknowing is to sin against Divine destiny!” For the World Spirit has implanted in us the power to have knowledge; and, when we do not will to acquire knowledge, we refuse what we really ought not to refuse, namely, to be a revelation of the World Spirit; and we represent more and more, not a revelation of the World Spirit, but a caricature, a distorted image of it. It is our duty to strive to become ever increasingly an image of the World Spirit. Only when we can give meaning to these words, “to become an image of the World Spirit”; only when it becomes significant for us in this sense to say, “We must learn to know, it is our duty to learn to know,” only then can we sense aright that feeling of reverence we have just demanded, in the presence of the Being of Man. And for one who wishes to reflect, in the occult sense, upon the life of man, upon the essential quality of man's being, this reverence before the nature of man is an absolute necessity, for the simple reason that it is the only thing capable of awakening our spiritual sight, our entire spiritual faculty for seeing and beholding the things of the spirit, of awakening those forces which permit us to penetrate into the spiritual foundation of man's nature. Anyone who, as seer and investigator of the Spirit, is unable to have the very highest degree of reverence in the presence of the nature of man, who cannot permeate himself to the very fibres of his soul with the feeling of reverence before man's nature, must remain with closed eyes (however open they may be for this or that spiritual secret of the world) to all that concerns what is really deepest in the Being of Man. There may be many clairvoyants who can behold this or that in the spiritual environment of our existence; yet, if this reverence is lacking, they lack also the capacity to see into the depths of man's nature, and they will not know how to say anything rightly with regard to what constitutes the Being of Man.

In the external sense the teaching about life is called physiology. This teaching should not here be regarded in the same way as in external science but as it presents itself to the spiritual eye; so that we may look beyond the forms of the outer man, beyond the form and functions of his physical organs into the spiritual, super-sensible foundation of the organs, of the life-forms and life processes. And since it is not our intention here to pursue this “occult physiology,” as it may be called, in any unreal way, it will be necessary in several cases to refer with entire candour to things which from the very beginning will sound rather improbable to anyone who is more or less uninitiated. At the same time, it may be stated that this cycle of lectures, even more than some others I have delivered, forms a whole, and that no single part of any one lecture, especially the earlier ones—for much that is to find expression in the course of this cycle will have to be affirmed without restraint—should be torn from its context and judged separately. On the contrary, only after having heard the concluding lectures will it be possible to form a judgment with regard to what really has been said. For this reason, therefore, it will be necessary to proceed in a somewhat different way, in this occult physiology, from that of external physiology. The foundations for our introductory statements will be confirmed by what meets us at the conclusion. We shall not be called upon to draw a straight line, as it were, from the beginning to the end; but we shall proceed in a circle so that we shall return again, at the end, to the point from which we started.

It is an examination, a study, of Man, that is to be presented here. At first he appears before our external senses in his outer form. We know, of course, that to what in the first place the layman with his purely external observation can know concerning man, there is to-day a very great deal which science has added through research. Therefore, when considering what we are able to know of the human being at the present time through external experience and observation, we must of necessity combine what the layman is in a position to observe in himself and others with what science has to say, including those branches of scientific observation which come to their results through methods and instruments worthy of our admiration.

If we bear in mind first, purely as regards external man, all that a layman may observe in him (or may perhaps have learned from some sort of popular description of the nature of man), then it will perhaps not seem incomprehensible if, from the very beginning, attention is called to the fact that even the outer shape of man, as it meets us in the outside world, really consists of a duality. And for anyone who wishes to penetrate into the depths of human nature, it is absolutely necessary that he becomes conscious of the fact, that even external man, as regards his form and stature, presents fundamentally a duality.

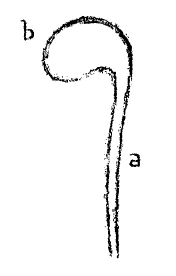

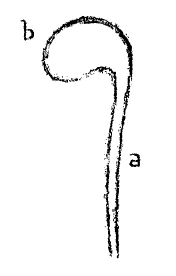

One part of man, which we can clearly distinguish, consists of everything that is to be found enclosed in organs affording the greatest protection against the outside world: that is, all that we may include within the region of the brain and the spinal cord. Everything belonging in this connection to the nature of man, to the brain and spinal cord, is firmly enclosed in a secure protective bony structure. Taking a side view, we observe that what belongs to these two systems may be illustrated in the following way. If a in this diagram represents all the super-imposed vertebrae along the whole length of the spinal cord, and b the cranium and the bones of the skull, then inside the canal which is formed by these super-imposed vertebrae, as well as by the bones of the skull, is enclosed everything belonging to the sphere of the brain and the spinal cord. One cannot observe the human being without becoming conscious of the fact that everything pertaining to this region forms a totality complete within itself; and that the rest of man (which we might group physiologically in the most varied ways, as the neck, the trunk, the limb-structure) keeps its connection with all that we reckon as brain and spinal cord by means of more or less thread-like or ribbon-shaped formations, pictorially speaking, which must first break through this protective sheath, in order that a connection may be brought about between the portion enclosed within this bony structure and the portion attached to it as exterior nature of man. Thus we may say that, even to a superficial observation, everything constituting man proves itself to be a duality, the one portion lying within the bony structure we have described, the firm and secure protective sheath, and the other portion without.

At this point we must cast a purely superficial glance at that which lies within this bony structure. Here again we can quite easily distinguish between the large mass embedded within the skull-bones in the form of a brain, and that other portion which is appended to it like a stalk or cord and which, while organically connected with the brain, extends in this thread-like outgrowth of the brain into the spinal canal. If we differentiate between these two structures we must at once call attention to something which external science does not need to consider, something of which occult science, however, since its task is to penetrate into the depths of the being of things, must indeed take note. We must call attention to the fact that everything which we consider as the basis of a study of man refers, in the first place, only to Man. For the moment we enter into the deeper fundaments of the separate organs, we become aware (and we shall see in the course of these lectures that this is true) that any one of these organs, through its deeper significance in the case of man, may have an entirely different task from that of the corresponding organ in the animal world. Or, to put it more exactly, anyone who looks upon such things with the help of ordinary external science will say: “What you have been telling us here may be just as truly affirmed with reference to the animals.” That which is said here, however, with reference to the essential nature of the organs in the case of the human being, cannot be said in the same way with regard to the animal. On the contrary the occult task is to consider the animal by itself, and to investigate whether that which we are in a position to state regarding man with reference to the spine and the brain, is valid also for animals. For the fact that the animals closely related to man also have a spine and a brain does not prove that these organs, in their deeper significance, have the same task in both man and animal; just as the fact that a man holds a knife in his hand does not indicate whether it is for the purpose of carving a piece of veal or in order to erase something. In both cases we have to do with a knife; and he who considers only the form of the knife, that is, the knife as knife, will believe that in both cases it amounts to the same thing. In both cases, he who stands on the basis of a science that is not occult will say that we have to do with a spinal cord and a brain; and he will believe, since the same organs are to be found in man and animal, that these organs must therefore have the same function. But this is not true. It is something that has become a habit of thought in external science, and has led to certain inaccuracies; and it can be corrected only if external science will accustom itself gradually to enter into what can be stated from out of the depths of super-sensible research regarding the different living beings.

Now, when we consider the spinal cord on the one hand, and the brain on the other, we can easily see that there is a certain element of truth in something already pointed out more than a hundred years ago by thoughtful students of nature. There is a certain rightness in the statement that when one observes the brain carefully it looks, so to speak, like a transformed spinal cord. This becomes all the more intelligible when we remember that Goethe, Oken, and other similarly reflective observers of nature, turned their attention primarily to the fact that the skull-bones bear certain resemblances of form to the vertebrae of the spine. Goethe, for example, was impressed very early in his reflections by the fact that when one imagines a single vertebra of the spinal column transformed, levelled and distended there may appear through such a reshaping of the vertebrae the bones of the head, the skull-bones; thus, if one should take a single vertebra and distend it on all sides so that it has elevations here and there, and at the same time is smooth and uniform in its expansions, the form of the skull might in this way be gradually derived from a single vertebra. Thus we may in a certain respect call the skull-bones reshaped vertebrae.

Now, just as we can look upon the skull-bones which enclose the brain as transformed vertebrae, as the transformation of such bones as enclose the spinal cord, so we may also think of the mass of the spinal cord distended in a different way, differentiated, more complex, till we obtain out of the spinal cord, so to speak, through this alteration, the brain. We might likewise, for instance, think how out of a plant, which at first has only green foliage, there grows forth the blossom. And so we might imagine that through the reshaping of a spinal cord, through its elevation to higher stages, the entire brain could be formed. (Later on, it will become clear how this matter is to be considered scientifically.) We may accordingly imagine our brain as a differentiated spinal cord.

Let us now look at both of these organs from this standpoint. Which of the two must we naturally look upon as the younger? Certainly not that one which shows the derived form, but rather the one which shows the original form. The spinal cord is at the first stage, it is younger; and the brain is at the second stage, it has gone through the stage of a spinal cord, is a transformed spinal cord, and is therefore to be considered as the older organ. In other words, if we fix our attention upon this new duality which meets us in man as brain and spinal cord, we may say that all the latent tendencies, all the forces, which lead to the building of a brain must be older forces in man; for they must first, at an earlier stage, have formed the tendency to a spinal cord, and must then have worked further toward the re-forming of this beginning of a spinal cord into a brain. A second start, as it were, must therefore have been made, in which our spinal cord did not progress far enough to reach the second stage but remained at the stage of the spinal cord. We have, accordingly, in this spine and nerve system (if we wish to express ourselves with pedantic exactness) a spine of the first order; and in our brain a spinal cord of the second order, a re-formed spinal cord which has become older—a spinal cord which once was there as such, but which has been transformed into a brain.

Thus we have, in the first place, shown with absolute accuracy just what we need to consider when we fix our attention objectively upon the organic mass enclosed; within this protective bony sheath. Here, however, something else must be taken into account, namely, something which really can confront us only in the field of occultism. A question may suggest itself, when for instance we speak as we have just been doing about the brain and the spinal cord, taking perhaps the following form: when such a re-formation as this takes place, from the plan of an organ at a first stage to the plan of an organ at a second stage, the evolutionary process may be progressive, or it may be retrogressive. That is, the process before us may either be one which leads to higher stages of perfection of the organ, or one which causes the organ to degenerate and gradually to die. We might say therefore, when we consider an organ like our spinal cord as it is to-day, that it seems to us to be at the present time a relatively young organ since it has not yet succeeded in becoming a brain. We may think about this spinal cord in two different ways. First, we may consider that it has in itself the forces through which it may also one day become a brain. In that case, it would be in a position to pass through a progressive evolution, and to become what our brain is to-day; or secondly, we may consider that it has not at all the latent tendency to attain to this second stage. In that case its evolution would be leading toward extinction; it would pass into decadence and be destined to suggest the first stage and not to arrive at the second. Now, if we reflect that the groundwork of our present brain is what was once the plan or beginning of a spinal cord, we see that that former spinal cord undoubtedly had in it the forces of a progressive evolution, since it actually did become a brain. If, on the other hand, we consider at this point our present spinal cord, the occult method of observation reveals that what to-day is our spinal cord has not within itself, as a matter of fact, the latent tendency to a forward-directed evolution, but is rather preparing to conclude its evolution at this present stage.

If I may express myself grotesquely, the human being is not called upon to believe that one day his spinal cord, which now has the form of a slender string, will be puffed out as the brain is puffed out. We shall see later what underlies the occult view, so as to enable us to say this. Yet, through this simple comparison of the form of this organ in man and in the lower animals, where it first appears, you will find an external intimation of what has just been stated. In the snake, for example, the spine adds on to itself a series of innumerable rings behind the head and is filled out with the spinal cord, and this spinal column extends both forward and backward indefinitely. In the case of man the spinal cord, as it extends downward from the point where it is joined to the brain, actually tends more and more to a conclusion, showing less and less clearly that formation which it exhibits in its upper portions. Thus, even through external observation, one may notice that what in the case of the snake continues its natural evolution rearward, is here hastening toward a conclusion, toward a sort of degeneration. This is a method of observation through external comparison, and we shall see how the occult view affects it.

To summarise, then, we may say that within the bony structure of the skull we have a spinal cord which through a progressive development has become a brain, and is now at a second stage of its evolution; and in our spinal cord we have, as it were, the attempt once again to form such a brain, an attempt, however, which is destined to fail and cannot reach its full growth into a real brain.

Let us now proceed from this reflection to that which can be known even from an external, layman's observation, to the functions of the brain and the spinal cord. It is more or less known to everyone that the instrument of the so-called higher soul-activities, is in a certain respect, in the brain, that these higher soul-activities are directed by the organs of the brain. Furthermore, it is recognised that the more unconscious soul-activities are directed from the spinal cord. I mean those soul-activities in which very little deliberation interposes itself between the reception of the external impression and the action which follows it. Consider for a moment how you jerk back your hand when it is stung. Not very much deliberation intervenes between the sting and the drawing back. Such soul-activities as these are in fact, and with a certain justification, even regarded by natural science in such a way as to attribute to them the spinal cord as their instrument.

We have other soul-activities in which a more mature reflection interposes itself between the external impression and that which finally leads to action. Take, for example, an artist who observes external nature, straining every sense and gathering countless impressions. A long time passes, during which he works over these impressions in an inner activity of soul. He then proceeds to establish after a long interval through outward action what has grown, in long-continued soul-activity, out of the external impressions. Here there intervenes, between the outer impression and that which the man produces as a result of the outer impression, a richer activity of soul. This is also true of the scientific investigator; and, indeed, of anyone who reflects about the things that he wishes to do, and does not rush wildly at every external impression, who does not as it were, in reflex action fly into a passion like a bull when he sees the colour red, but thinks about what he wishes to do. In every instance where reflection intervenes, we encounter the brain as an instrument of soul-activity.

If we go still deeper into this matter we may say to ourselves: True, but how then does this soul-activity of ours, in which we use the brain, manifest itself? We perceive, to begin with, that it is of two different kinds, one of which takes place in our ordinary waking day-consciousness. In this consciousness we accumulate, through the senses, external impressions; and these we work over by means of the brain in rational reflection. To express it in popular language—we shall have to go into this still more accurately—we must picture to ourselves that these outer impressions find their way inside us through the doors of the senses, and stimulate certain processes in the brain. If we should wish, purely in connection with the external organisation, to follow what there takes place, we should see that the brain is set into activity through the stream of external impressions flowing into it; and that what this stream becomes, as a result of reflection, that is the deeds, the actions, which we ascribe to the instrumentality of the spinal cord.

Then, there also mingles in human life as it is to-day, between the wide-awake life of day and the unconscious life of sleep, the picture-life of dreams. This dream-life is a remarkable intermingling of the wide-awake life of day, which lays full claim to the instrument of our brain, and the unconscious life of sleep. Merely in outline, in a way that the lay thinker may observe for himself, we will now say something about this life of dreams.

We see that the whole of the dream-life has a strange similarity, from one aspect, to that subordinate soul-activity which we associate with the spinal cord. For, when dream-pictures emerge in our soul they do not appear as representations resulting from reflection, but rather by reason of a certain necessity, as, for instance, a movement of the hand results when a fly settles on the eye. In this latter case an action takes place as an immediate, necessary movement of defense. In dream-life something different appears, yet likewise because of an immediate necessity. It is not an action which here appears but rather a picture upon the horizon of the soul. Yet, just as we have no deliberate influence upon the movement of the hand in the wide-awake life of day, but make this movement of necessity, even so do we have no influence over the way that dream-pictures shape themselves, as they come and go in the chaotic world of dreams. We might say, therefore, that if we look at a man during his wide-awake life of day, and see something of what goes on within him in the form of reflex movements of all sorts, when he does things without reflecting, in response to external impressions; if we observe the sum-total of gestures and physiognomic expressions which he accomplishes without reflection, we then have a sum of actions which through necessity become a part of this man as soul-actions. If we now consider a dreaming man we have a sum of pictures, in this case something possessing the character not of action but of pictures, which work into and act upon his being. We may say, therefore, that just as in the wakeful life of day those human actions are carried out which arise and take shape without reflection, so do the dream-conceptions, chaotically flowing together, come about within a world of pictures.

Now, if we look back again at our brain, and wished to consider it as being in a certain way the instrument also of the dream-consciousness, what should we have to do? We should have to suppose that there is in some way or other something inside the brain which behaves in a way similar to the spinal cord that guides the unconscious actions. Thus, we have, as it were, to look upon the brain as primarily the instrument of the wide-awake soul-life, during which we create our concepts through deliberation, and underlying it a mysterious spinal cord which does not express itself; however, as a complete spinal cord but remains compressed inside the brain, and does not attain to actions. Whereas our spinal cord does attain to actions, even though these are not brought about through deliberation; the brain in this case induces merely pictures. It stops midway, this mysterious thing which lies there like the groundwork of a brain. Might we not say, therefore, that the dream-world enables us in a most remarkable way to point, as in a mystery, to that spinal cord lying there at the basis of the brain?

If we consider the brain, in its present fully-developed state, as the instrument of our wide-awake life of day, its appearance for us is that which it has when removed from the cavity of the skull. Yet there must be something there, within, when the wakeful life of day is blotted out. And here occult observation shows us that there actually is, inside the brain, a mysterious spinal cord which calls forth dreams. If we should wish to make a drawing of it, we could represent it in such a way that, within the brain which is connected with the world of ideas of the life of day, we should have an ancient mysterious spinal cord, invisible to external perception, in some way or other secreted inside it. I shall first state quite hypothetically that this spinal cord becomes active when man sleeps and dreams, and is active at that time in a manner characteristic of a spinal cord, namely, that it calls forth its effects through necessity. But, because it is compressed within the brain, it does not lead to actions, but only to pictures and picture-actions; for in dreams we act, as we know, only in pictures. So that because of this peculiar, strange, chaotic life that we carry on in dreams, we should have to point to the fact that underlying the brain, which we quite properly consider to be the instrument of our wide-awake life of day, is a mysterious organ which perhaps represents an earlier form of the brain—which has evolved itself to its present state out of this earlier form—and that this mysterious organ is active to-day only when the new form is inactive. It then reveals what the brain once was. This ancient spinal cord conjures up what is possible, considering the way it is enclosed, and induces, not completed actions, but only pictures.

Thus the observation of life leads us, of itself, to separate the brain into two stages. The very fact that we dream indicates that the brain has passed through two stages and has evolved to the wide-awake life of day. When, however, this wakeful day-time life is stilled, the ancient organ again exerts itself in the life of dreams. Thus we have first made types out of what external observation of the world furnishes us, which shows us that even observation of the soul-life adds meaning to what a consideration of the outer form can give us, namely, that the wide-awake life of day is related to dream-life in the same way as the perfected brain at the second stage of its evolution is related to its groundwork, to the ancient spinal cord which is at the first stage of its evolution. In a remarkable way, which we shall justify in the following lectures, occult, clairvoyant vision can serve us as a basis for a comprehensive observation of human nature, as it expresses itself in those organs enclosed within the bony mass of the skull and vertebrae.

In this connection you already know, from spiritual-scientific observations, that man's visible body is only one part of the whole human being, and that in the moment the seer's eye is opened the physical body reveals itself as enclosed, embedded, in a super-sensible organism, in what, roughly speaking, is called the “human aura.” For the present this may be here affirmed as a fact, and later we shall return to it to see how far the statement is justified. This human aura, within which physical man is simply enclosed like a kernel, shows itself to the seer's eye as having different colours. At the same time, we must not imagine that we could ever make a picture of this aura, for the colours are in continual movement; and every picture of it, therefore, that we sketch with pigment can be only an approximate likeness, somewhat in the same way that it is impossible to portray lightning, since one would always end by painting it only as a stiff rod, a rigid image. Just as it is never possible to paint lightning, so is it even less possible to do this in the case of the aura, because of the added fact that the auric colours are in themselves extraordinary unstable and mobile. We cannot, therefore, express it otherwise than to say that at best we are representing it symbolically.

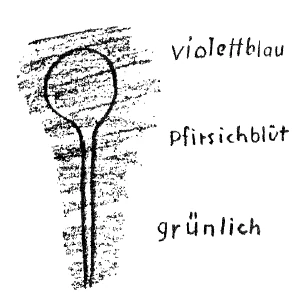

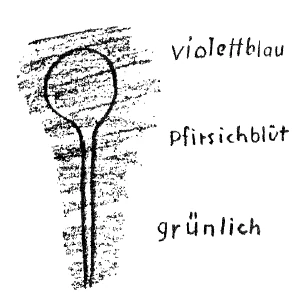

Now, these auric colours show themselves as differing very remarkably, depending upon the fundamental character of the whole human organism. And it is interesting to call attention to the auric picture which presents itself to the clairvoyant eye, if we imagine the cranium and the spine observed from the rear. There we find that the appearance of that portion of the aura belonging to this region is such that we can only describe the whole man as embedded in the aura. Although we must remember that the auric colours are in a state of movement within the aura, yet it is evident that one of the colours is especially distinct, namely around the lower parts of the spine. We may call this greenish. And again we may mention another distinct colour, which does not in any other part of the body appear so beautiful as here, around the region of the brain; and this in its ground-tone is a sort of lilac-blue. You can get the best conception of this lilac-blue if you imagine the colour of the peach-blossom; yet even this is only approximate. Between this lilac-blue of the upper portion of the brain, and the green of the lower parts of the spine, we have other colour nuances surrounding the human being which are hard to describe, since they do not often appear among the ordinary colours present in the surrounding world of the senses. Thus, for instance, adjoining the green is a colour which is neither green, blue, nor yellow, but a mixture of all three. In short, there appear to us, in this intermediate space, colours which actually do not exist in the physical world of sense. Even though it is difficult to describe what is here within the aura, one thing may nevertheless be stated positively: beginning above with the puffed-out spinal cord, we have lilac-blue colour and then, coming down to the end of the spine, we have a more distinctly greenish shade.

This I wish to state as a fact, along with what has been said to-day in connection with a purely external observation of the human form and of human conduct. Following this, we shall endeavour to observe also that other part of the human being which is attached to the portion we have discussed to-day, in the form of neck, trunk, limbs, etc., as constituting the second part of the human duality, to the end that we may then be able to proceed to a consideration of what is presented to us in the complete interaction of this human duality.

Erster Vortrag

In diesem Vortragszyklus, der auf Veranlassung unserer Prager Freunde gehalten wird, soll ein Thema behandelt werden, welches dem Menschen ungeheuer naheliegt, weil es ja das genauere Wesen des Menschen unmittelbar berührt und von dem handelt, was sich auf sein physisches Leben selber bezieht. Wenn dieses Thema auch auf der einen Seite dem Menschen so naheliegt, weil es ihn ja selbst betrifft, so darf man doch sagen, daß es auf der anderen Seite ein sehr schwer zugängliches Thema ist. Denn schon der Blick auf die durch alle Zeiten, man möchte sagen, aus mystisch-okkulten Höhen an den Menschen dringende Forderung «Erkenne dich selbst» zeigt uns die Tatsache, daß Selbsterkenntnis, wirkliche, wahre Selbsterkenntnis, im Grunde genommen dem Menschen recht schwierig ist, und das bezieht sich nicht nur auf die individuelle, persönliche Selbsterkenntnis, sondern vor allen Dingen auch auf die Erkenntnis der menschlichen Wesenheit überhaupt. Und weil der Mensch — wie man sehen kann aus dieser ewigen Forderung «Erkenne dich selbst» - sich selbst seiner Wesenheit nach so sehr fernsteht, einen so weiten Weg hat, um sich selbst zu verstehen, deshalb wird in einer gewissen Beziehung das, was Gegenstand der folgenden Betrachtungen dieser Tage werden wird, als etwas Fernliegendes erscheinen, zu dessen Verständnis sehr Verschiedenes notwendig ist. Nicht ohne Grund ging ich selbst erst nach längerer Zeit und reiflicher Überlegung daran, auch einmal über dieses Thema zu sprechen. Denn es ist ein Thema, demgegenüber — soll man zu einer wahren, wahrhaften Betrachtung kommen — etwas unbedingt notwendig ist, was bei einer gewöhnlichen wissenschaftlichen Betrachtung so oft außer acht gelassen wird: Notwendig ist, daß man vor der Wesenheit des Menschen — wohlgemerkt, nicht vor der Wesenheit des einzelnen Menschen, insbesondere dann nicht, wenn dieser einzelne Mensch wir selber sind —, daß man vor dem Wesen des Menschen im allgemeinen Ehrfurcht habe. Und es muß als eine Grundbedingung für unsere folgenden Betrachtungen angesehen werden, daß man Ehrfurcht habe vor dem, was die menschliche Wesenheit in Wahrheit bedeutet.

Wie kann man denn davor wahrhafte Ehrfurcht haben? Auf keine andere Art, als daß man zunächst absieht von dem, wie der Mensch — ganz gleichgültig, ob wir selbst oder ein anderer — uns im alltäglichen Leben erscheint, und indem man sich aufschwingt zu der Anschauung: Dieser Mensch mit seiner gesamten Entwickelung ist nicht um seiner selbst willen da, er ist da zur Offenbarung des Geistes, der ganzen Welt des Göttlich-Geistigen, er ist eine Offenbarung der Weltengottheit, des Weltengeistes. Und für diejenigen, die erkennen, daß alles, was uns umgibt, Ausdruck ist für göttlich-geistige Kräfte, für die ist es auch möglich, diese Ehrfurcht zu empfinden, nicht nur für das Göttlich-Geistige selbst, sondern auch für die Offenbarungen dieses Göttlich-Geistigen. Und wenn wir davon sprechen, daß der Mensch nach immer vollkommenerer Selbsterkenntnis trachte, so sollen wir uns darüber klar sein, daß nicht bloß Neugierde, meinetwillen auch Wißbegierde, uns veranlassen soll, nach Selbsterkenntnis zu streben, sondern daß wir es als Pflicht empfinden müssen, die Erkenntnis der Offenbarungen des Weltengeistes durch den Menschen immer vollkommener und vollkommener zu gestalten. In diesem Sinne sind die Worte zu verstehen: Unwissend zu bleiben, wo Erkenntnis möglich ist, bedeutet eine Versündigung gegen die göttliche Bestimmung des Menschen. Denn der Weltengeist hat in uns die Kraft gelegt, wissend zu werden; und wenn wir nicht erkennend werden wollen, so lehnen wir es ab — was wir eigentlich nicht dürften —, eine Offenbarung des Weltengeistes zu sein, und stellen immer mehr und mehr nicht eine Offenbarung des Weltengeistes dar, sondern eine Karikatur, ein Zerrbild von ihm. Es ist unsere Pflicht, nach Erkenntnis zu streben, um immer mehr und mehr ein Bild des Weltengeistes zu werden. Erst wenn wir mit diesen Worten einen Sinn verbinden können, «ein Bild des Weltengeistes zu werden», erst wenn es uns bedeutungsvoll wird, in diesem Sinne zu sagen: Wir müssen erkennen, es ist unsere Pflicht zu erkennen -, erst dann können wir das vorhin geforderte Gefühl von Ehrfurcht gegenüber der Wesenheit des Menschen so recht empfinden. Und für den, der im okkulten Sinne das Leben des Menschen, das Wesen des Menschen betrachten will, für den ist diese Durchdringung mit Ehrfurcht vor der menschlichen Natur schon deshalb eine unbedingte Notwendigkeit, weil diese Durchdringung mit Ehrfurcht einzig und allein geeignet ist, unsere geistigen Augen und unsere geistigen Ohren, unser ganzes geistiges Schauvermögen wachzurufen, das heißt diejenigen Kräfte, die uns eindringen lassen in die geistigen Untergründe der menschlichen Natur. Wer als Seher, als Geistesforscher nicht im höchsten Grade Ehrfurcht haben könnte vor der menschlichen Natur, wer sich nicht durchdringen kann bis in die innersten Fibern seiner Seele mit dem Gefühl von Ehrfurcht gegenüber der Menschennatur, dem Abbild des Geistes, dem bliebe das Auge, wenn es noch so geöffnet ist für diese oder jene geistigen Geheimnisse der Welt, verschlossen für alles das, was sich auf die eigentlich tiefere Wesenheit des Menschen selber bezieht. Und es mag viele Hellseher geben, welche dieses oder jenes schauen können in dem geistigen Umkreis unseres Daseins: Wenn ihnen diese Ehrfurcht fehlt, dann fehlt ihnen das Vermögen, in die Tiefen der menschlichen Natur hineinzuschauen, und sie werden nichts Richtiges über das zu sagen wissen, was des Menschen Wesenheit ist.

Man nennt ja die Lehre von den Lebensvorgängen des Menschen «Physiologie». Diese Lehre soll hier nicht in der Weise betrachtet werden, wie es in der äußeren Wissenschaft geschieht, sondern so, wie sie dem geistigen Auge sich darbietet, so daß wir von den äußeren Gestaltungen des Menschen, von der Form und den Lebensvorgängen seiner Organe immer hinblicken auf die geistige, übersinnliche Grundlage der Organe, der Lebensformen, der Lebensprozesse. Und da nicht die Absicht besteht, diese «okkulte Physiologie», wie man auch sagen könnte, in irgendeiner unsachlichen Weise hier zu treiben, so wird es notwendig sein, daß in einer gewissen unbefangenen Weise an manchen Stellen Hindeutungen gemacht werden auf Dinge, welche dem mehr oder weniger Außenstehenden am Anfang recht unwahrscheinlich klingen werden. Es muß ausdrücklich betont werden, daß dieser Vortragszyklus, noch mehr als mancher andere, den ich gehalten habe, ein Ganzes bildet und daß aus einzelnen Vorträgen, insbesondere aus den Anfangsvorträgen, nichts aus dem Zusammenhang herausgerissen beurteilt werden kann, weil manches unbefangen wird gesagt werden müssen. Und erst, wenn man die Schlußvorträge gehört haben wird, wird man sich ein Urteil bilden können über das, was eigentlich gesagt werden soll. Denn das Thema wird hier in einer etwas anderen Weise behandelt werden als in der äußeren Physiologie. Die Anfangsgründe werden sich auch bestätigen durch das, was uns zuletzt entgegentreten wird. Wir werden sozusagen nicht eine gerade Linie vom Anfang bis zum Ende zu beschreiben haben, sondern wir werden in einer Kreislinie vorgehen, so daß wir am Ende dort wieder ankommen, von wo wir ausgegangen sind.

Eine Betrachtung des Menschen soll es sein, was hier dargeboten wird. Zunächst tritt uns dieser Mensch für die äußeren Sinne seiner äußeren Form nach entgegen. Wir wissen ja, daß zu dem, was zunächst die reine äußere laienhafte Betrachtung über den Menschen wissen kann, heute schon sehr vieles kommt, was die Wissenschaft hinzuerforscht hat. Daher müssen wir das, was wir in äußerer Weise, aus der äußeren Erfahrung und Beobachtung über den Menschen heute wissen können, notwendigerweise zusammenstellen aus dem, was schon der Laie an sich und an anderen Menschen zu beobachten in der Lage ist, und dem, was der Wissenschaft gelungen ist zu erforschen, welche durch bewunderungswürdige Methoden, durch bewunderungswürdige Instrumente zu ihren Resultaten über die Leiblichkeit des Menschen kommt.

Wenn man alles zusammenhält, was man als Laie rein äußerlich am Menschen sehen kann, was man vielleicht auch schon aus irgendwelchen populären Beschreibungen kennengelernt hat, dann wird es vielleicht nicht unverständlich sein, wenn darauf aufmerksam gemacht wird, daß schon die äußere Gestalt des Menschen, wie sie uns in der Außenwelt entgegentritt, aus einer Zweiheit besteht. Für den, der in die Tiefen der Menschennatur eindringen will, ist es durchaus notwendig, sich bewußt zu werden, daß schon der äußere Mensch seiner Form und Gestaltung nach im Grunde genommen eine Zweiheit darstellt.

Das eine, das wir am Menschen deutlich unterscheiden können, ist alles das, was sich als eingeschlossen erweist in Organe, die den größtmöglichen Schutz gegen die Außenwelt gewähren. Es ist alles das, was wir zählen können zum Bereich des Gehirns und des Rükkenmarkes. Alles, was in dieser Beziehung zur menschlichen Natur gehört, zu Gehirn und Rückenmark, ist fest umschlossen von sicheren, Schutz gewährenden Knochengebilden. Wenn wir schematisch darstellen wollen, was zu diesen beiden Bereichen gehört, so können wir uns das in folgender Weise veranschaulichen: Wenn a (siehe Zeichnung) schematisch darstellt die Summe der übereinandergelagerten Wirbelknochen, die längs des Rückenmarkes verlaufen, b die Schädeldecke und die Schädelknochen, so ist eingeschlossen innerhalb des Kanales, der gebildet wird durch die übereinandergelagerten Wirbelknochen sowie durch die Knochen des Schädels, alles, was in den Bereich des Gehirns und des Rückenmarkes gehört. Man kann den Menschen nicht betrachten, ohne sich bewußt zu werden, daß alles, was in diesen Bereich gehört, im Grunde genommen eine in sich geschlossene Ganzheit bildet und daß alles übrige vom Menschen, das wir in verschiedenster Weise physiologisch angliedern können — Hals, Rumpf, Gliedmaßengebilde -, mit Gehirn und Rückenmark in Verbindung steht durch, bildlich gesprochen, mehr oder weniger fadenförmige oder bandförmige Gebilde. Diese müssen erst die Schutzhülle durchbrechen, damit eine Verbindung hergestellt werden kann mit dem innerhalb dieser Knochengebilde eingeschlossenen Teil. So können wir sagen: Es erweist sich schon einer oberflächlichen Betrachtung gegenüber alles, was am Menschen ist, als eine Zweiheit; das eine liegt innerhalb der charakterisierten Knochengebilde in festen und sicheren Schutzhüllen, das andere außerhalb derselben.

Nun müssen wir zunächst einen ganz oberflächlichen Blick auf das werfen, was innerhalb dieser Knochengebilde liegt. Da können wir wieder leicht unterscheiden zwischen jener großen Masse, die in die Schädelknochen eingebettet ist als Gehirn, und dem anderen Teil, der wie ein Stiel oder Strang daranhängt, der in organischer Verbindung mit dem Gehirn steht und sich wie eine Art fadenförmiger Auswuchs desselben in den Rückgratkanal hineinstreckt, das Rückenmark. Wenn wir diese zwei Gebilde voneinander unterscheiden, dann müssen wir schon auf etwas aufmerksam machen, worauf die äußere Wissenschaft nicht aufmerksam zu machen braucht, worauf aber die okkulte Wissenschaft, die in die Tiefe des Wesens der Dinge einzudringen hat, wohl aufmerksam machen muß. Es muß darauf aufmerksam gemacht werden, daß alles, was wir auf dem Boden einer Betrachtung über den Menschen sagen, sich zunächst nur auf den Menschen bezieht. Denn in dem Augenblick, wo man in die tieferen Gründe der einzelnen Organe eindringt, wird man gewahr — wir werden im Laufe der Vorträge schon sehen, daß es so ist -—, daß ein Organ eine ganz andere Aufgabe haben kann in seiner tieferen Bedeutung beim Menschen als ein ähnliches oder gleichartiges Organ in der tierischen Welt. Wer in der gewöhnlichen äußeren Wissenschaft die Dinge betrachtet, wird sagen: Was du uns hier gesagt hast, kann man ja auch sagen in bezug auf die Säugetiere. - Aber, was über die Bedeutung der Organe in bezug auf den Menschen gesagt wird, das kann nicht, wenn man tiefer in die Sache dringt, in gleicher Weise für die Tiere gesagt werden, sondern die okkulte Wissenschaft hat die Aufgabe, die Tiere für sich zu betrachten und nachzusehen, ob dasselbe, was für den Menschen in bezug auf Rückenmark und Gehirn zu sagen ist, auch für die Tiere gilt. Denn daß die Tiere, die dem Menschen nahestehen, auch Rückenmark und Gehirn haben, das beweist noch nicht, daß diese Organe für Mensch und Tier dieselben Aufgaben haben, so wie man, um einen Vergleich zu gebrauchen, ein Messer in der Hand haben kann, um damit meinetwillen ein Kalb zu tranchieren oder auch um damit zu radieren. Beide Male hat man es mit einem Messer zu tun, und wer nur Rücksicht nimmt auf die Form des Messers, der wird glauben, daß es sich in beiden Fällen um dasselbe handelt. In derselben Lage wäre derjenige, welcher glaubt, weil sich bei Mensch und Tier dieselben Organe Gehirn und Rückenmark - finden, so würden diese zu denselben Verrichtungen dienen. Das ist aber nicht wahr. Das ist etwas, was in der äußeren Wissenschaft gang und gäbe geworden ist und zu gewissen Ungenauigkeiten geführt hat und was nur wird korrigiert werden können, wenn sich die äußere Wissenschaft dazu bequemen wird, allmählich auf das einzugehen, was aus den Tiefen der übersinnlichen Forschung über die Charaktere der Wesenheiten gesagt werden kann.

Wenn wir nun betrachten das Rückenmark auf der einen Seite, das Gehirn auf der anderen Seite, so werden wir leicht sehen, daß das eine gewisse Wahrheit hat, worauf denkende Naturbetrachter schon seit mehr als hundert Jahren aufmerksam gemacht haben. Es hat eine gewisse Richtigkeit zu sagen: Wenn man das Gehirn betrachtet, so ‚sieht es gleichsam aus wie ein umgebildetes Rückenmark. — Das wird ja noch leichter begreiflich, wenn man sich daran erinnert, daß Goethe, Oken und andere Naturbetrachter vor allen Dingen den Blick darauf gerichtet haben, daß die Schädelknochen gewisse Formähnlichkeiten haben mit den Wirbelknochen des Rückgrates. Es war Goethe, der die Formähnlichkeiten der Organe aufmerksam betrachtet hat, sehr früh in seinen Betrachtungen aufgefallen, daß, wenn man einzelne Wirbelknochen sich umgestaltet denkt, verflacht und aufgetrieben, daß man dann durch eine solche Umgestaltung der Wirbelknochen zum Kopfknochen, zum Schädelknochen kommt. Gleichsam dadurch, daß man einen Wirbelknochen nach allen Seiten aufbläst, so daß er flach wird in seinen Ausdehnungen, wird man nach und nach aus einem Wirbelknochen die Form des Schädelknochens ableiten können. So kann man in einer gewissen Beziehung die Schädelknochen umgestaltete Wirbelknochen nennen. Geradeso nun, wie man die Schädelknochen, die das Gehirn umschließen, als umgebildete Wirbelknochen ansehen kann, so kann man sich die Masse des Rückenmarkes gleichsam aufgetrieben denken, differenzierter, komplizierter gemacht, und man bekommt aus dem Rückmark, gewissermaßen durch Umwandlung, das Gehirn. So etwa, wie eine Pflanze, die zunächst nur grüne Blätter hat, diese umbildet, differenziert, um buntfarbige Blütenblätter hervorzubringen, wie also die Blüten differenzierte Blätter sind, so können wir uns denken, daß durch Umgestaltung, durch Differenzierung der Form, durch Heraufheben des Rückenmarkes auf eine höhere Stufe, das Gehirn gebildet werden konnte. Man kann sich also vorstellen, daß wir in unserem Gehirn ein differenziertes Rückenmark sehen können.

Nun schauen wir von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus uns die beiden Organe an. Welches dieser Organe müssen wir auf natürliche Weise als das jüngere betrachten? Das ist die Frage, die wir uns vorlegen müssen. Doch zweifellos nicht dasjenige, welches die abgeleitete Form zeigt, sondern das, welches die ursprüngliche Form hat. Das heißt, wir müssen uns denken, das Rückenmark steht auf einer ersten Stufe der Entwickelung, es ist jünger, und das Gehirn steht auf einer zweiten Stufe. Es hat zuerst die Stufe des Rückenmarkes durchgemacht, es ist ein verwandeltes Rückenmark und ist also als das ältere Organ zu betrachten. Mit anderen Worten, wenn wir diese neue Zweiheit, die uns am Menschen als Gehirn und Rückenmark entgegentritt, ins Auge fassen, so können wir sagen: Es müssen alle Kräfte, die zur Gehirnbildung führten, ältere Kräfte sein, denn sie müssen auf einer früheren Stufe erst die Anlage zum Rückenmark gebildet haben und dann weitergewirkt haben zur Umbildung des Rückenmarkes zum Gehirn. Es muß also gleichsam ein zweiter Ansatz gemacht worden sein in unserem Rückenmark, das als solches noch nicht so weit fortgeschritten ist, sondern eben stehengeblieben ist auf einer früheren Stufe der Entwickelung. Wir haben also, wenn wir uns jetzt pedantisch genau ausdrücken wollen, in dem RückenmarkNervensystem ein Rückenmark erster Ordnung zu sehen und in unserem Gehirn ein Rückenmark zweiter Ordnung, ein umgebildetes älteres Rückenmark, ein Rückenmark, das einmal ein solches war, aber zum Gehirn umgebildet worden ist.

Damit haben wir zunächst in ganz genauer Weise auf das hingewiesen, was notwendig in Betracht zu ziehen ist, wenn wir die Organmassen, welche innerhalb dieser Knochenschutzhüllen eingeschlossen sind, sachgemäß ins Auge fassen wollen. Nun aber kommt etwas anderes in Betracht, was uns erst auf dem Felde des Okkultismus entgegentreten kann. Man kann eine Frage aufwerfen, nämlich: Wenn eine solche Umbildung stattfindet von einer Organanlage erster Stufe zu einer Organanlage zweiter Stufe, ist dann der Entwikkelungsprozeß ein fortschreitender oder ein rückläufiger? Das heißt, kann es ein solcher Prozeß sein, der zu höheren Vollkommenheitsstufen eines Organes führt, oder aber ein solcher Prozeß, der das Organ zum Degenerieren, zum allmählichen Absterben bringt? Betrachten wir ein Organ wie zum Beispiel unser Rückenmark. So wie es jetzt ist, so erscheint es uns als ein verhältnismäßig wenig fortgeschrittenes Organ, man könnte es als jung bezeichnen, denn es hat es noch nicht dahin gebracht, ein Gehirn zu werden. Wir können aber in zweifacher Weise über dieses Rückenmark denken. Einmal können wir uns denken, es habe in sich die Kräfte, auch einmal ein Gehirn zu werden, dann ist es in fortschreitender Entwickelung. Oder es habe gar nicht die Anlage dazu, diese zweite Stufe je zu erreichen, dann wäre es in absteigender Entwickelung, es würde in die Dekadenz gehen und bestimmt sein, die erste Stufe anzudeuten, jedoch nicht zur zweiten Stufe zu kommen. Wenn wir uns nun denken, daß unserem jetzigen Gehirn einmal ein Rückenmark zugrunde gelegen hat, so hat das damalige Rückenmark zweifellos fortschreitende Kräfte gehabt, denn es ist ja zum Gehirn geworden. Fragen wir uns aber jetzt nach unserem jetzigen Rückenmark, dann sagt uns die okkulte Betrachtungsweise: So wie unser Rückenmark heute ist, hat es in der Tat nicht in sich die Anlage zu einer fortschreitenden Entwickelung, sondern es bereitet sich vor, seine Entwickelung auf der gegenwärtigen Stufe abzuschließen. -— Wenn ich mich grotesk ausdrücken darf: Der Mensch hat nicht zu glauben, daß er einmal sein Rückenmark, wie es heute ist in Form eines dünnen Stranges, so aufgeplustert haben wird wie das heutige Gehirn. Wir werden noch sehen, was der okkulten Betrachtung zugrunde liegt, um so etwas sagen zu können. Schon aus einem reinen Vergleiche der Form dieses Organes, des Rückenmarkes, wie es beim Menschen auftritt und wie beim Tiere, sehen Sie eine äußere Hindeutung auf das, was jetzt gesagt worden ist. Da sehen Sie, wenn Sie zum Beispiel eine Schlange nehmen, wie in unzähligen Ringen hinter dem Kopf das Rückgrat ansetzt, ausgefüllt ist vom Rückenmark und wie das Rückgrat in einer Art gebildet ist, die fast endlos so weiter verlaufen könnte. Beim Menschen sehen wir, wie das Rückenmark von der Stelle, wo es sich an das Gehirn ansetzt, nach unten zu verlaufend, in der Tat immer mehr und mehr sich zusammenschließt und nach unten hin immer undeutlicher und undeutlicher jene Bildung zeigt, die es in den oberen Partien aufweist. So kann auch durch die äußere Betrachtung schon auffallen, wie das, was sich bei der Schlange nach rückwärts fortsetzt, beim Menschen einem Abschluß, einer Art Degeneration zueilt. Das ist zunächst eine äußere vergleichende Betrachtungsweise. Wir werden sehen, wie sich die okkulte Betrachtung ausnimmt.

Wenn wir dies jetzt zusammenhalten, so dürfen wir sagen: Wir haben eingeschlossen in jenes Knochengebilde des Schädels ein Rükkenmark, das in fortschreitender Bildung zum Gehirn geworden ist, das auf einer zweiten Stufe seiner Entwickelung steht. Und wir haben gleichsam noch einmal einen Versuch, ein solches Gehirn zu bilden in unserem Rückenmark, aber einen Versuch, der schon jetzt zeigt, daß er nicht gelingen wird.

Sehen wir jetzt von dieser Betrachtung ab und gehen zu dem über, was wir auch wieder schon aus einer äußeren laienhaften Betrachtung kennen: zu den Aufgaben, die Gehirn und Rückenmark zu erfüllen haben. Es ist ja jedem mehr oder weniger bekannt, daß das Werkzeug für die sogenannten höheren Seelentätigkeiten das Gehirn ist, daß diese höheren Seelentätigkeiten von dem Organ des Gehirns dirigiert werden. Es ist weiterhin jedem bekannt, daß die mehr unbewußten Seelentätigkeiten vom Rückenmark und den sich anschließenden Nerven dirigiert werden, diejenigen Seelentätigkeiten nämlich, bei welchen zwischen dem äußeren Eindruck und der Handlung, die auf den äußeren Eindruck folgt, wenig Überlegung sich einschiebt. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel von einem Insekt in die Hand gestochen werden, ziehen Sie die Hand zurück, Sie zucken zurück; da schiebt sich zwischen Stich und Zurückziehen der Hand keine große Überlegung ein. Diese Seelentätigkeiten werden mit Recht schon von der äußeren Wissenschaft so angesehen, daß ihnen als ihr Werkzeug das Rückenmark zugeteilt ist. Wir haben andere Seelentätigkeiten, bei denen sich zwischen den äußeren Eindruck und das, was zuletzt zur Handlung führt, eine reichere Überlegung einschiebt; diese haben ihr Organ im Gehirn. Denken Sie, um gleich ein markantes Beispiel zu nehmen, an einen Künstler, der die äußere Natur betrachtet, der seine Sinne anstrengt und unzählige Eindrücke sammelt; dann geht eine lange Zeit vorüber, in der er diese Eindrücke in seiner Seele verarbeitet. Endlich, oft erst nach Jahren, geht er dazu über, das, was aus den äußeren Eindrücken in langer Seelentätigkeit geworden ist, durch äußere Handlungen zu fixieren. Da schiebt sich zwischen äußeren Eindruck und das, was durch den Menschen aus dem äußeren Eindruck gemacht wird, eine reichere Seelentätigkeit ein. Dasselbe ist auch beim wissenschaftlichen Forscher der Fall, aber auch bei jedem Menschen, der sich die Dinge, die er tun will, überlegt und nicht wild darauflosstürzt wie ein Stier, wenn er rote Farbe sieht. Überall, wo der Mensch nicht aus einer Reflexbewegung handelt, sondern sich seine Handlungen überlegt, sprechen wir vom Gehirn als einem Werkzeug der Seelentätigkeit.

Wenn wir noch tiefer auf diese Sache eingehen, werden wir uns fragen: Ja, wie zeigt sich denn diese unsere Seelentätigkeit, für welche wir das Gehirn als Werkzeug in Anspruch nehmen? Sie zeigt sich in zweifacher Art. Zunächst werden wir sie gewahr in unserem wachen Tagesleben. Was tun wir da? Wir sammeln durch die Sinne die äußeren Eindrücke und verarbeiten diese durch das Gehirn durch vernünftige Überlegung. Wir müssen uns vorstellen, daß die äußeren Eindrücke durch die Tore der Sinne in uns hineinwandern und gewisse Prozesse in unserem Gehirn anregen. Wenn wir hineinblikken könnten in das Gehirn und in das, was da geschieht, so würden wir sehen, wie unser Gehirn in Tätigkeit versetzt wird durch den sich hineinergießenden Strom der äußeren Eindrücke, und wir würden sehen, was aus diesen Eindrücken wird durch das, was die menschliche Überlegung bewirkt. Wir würden dann sehen, wie sich hinzugesellen auch die weniger von Überlegung beeinflußten Folgen dieser Eindrücke, das heißt Taten und Handlungen, die wir mehr seinem Werkzeug, dem Rückenmark, zuzuschreiben haben.

Jetzt müssen wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit richten auf die zwei Zustände, in welchen der heutige Mensch das ganze Leben hindurch abwechselnd lebt, das wache Tagesleben und das bewußtlose Schlafleben. Aus früheren Vorträgen ist es uns geläufig, daß am Tage die vier Wesensglieder des Menschen zusammen sind, während beim Schlafen Astralleib und Ich sich herausheben. Nun kennen wir alle jenen eigentümlichen Zustand, der sich mischt zwischen das wache Tagesleben und das bewußtlose Schlafleben: das Traumleben. Es soll zunächst in keiner anderen Weise über das Traumleben gesprochen werden als so, wie es der Laie beobachten kann. Wir sehen, daß das Traumleben eine merkwürdige Ähnlichkeit hat mit jener untergeordneten Seelentätigkeit, die wir an das Rückenmark knüpfen. Denn wenn die Iraumbilder auftreten in unserer Seele, treten sie nicht auf als Vorstellungen, die der Überlegung entspringen, sondern sie treten mit Notwendigkeit auf, ähnlich wie etwa die unwillkürliche Handbewegung auftritt, wenn wir eine Fliege verjagen, die sich auf unsere Hand setzt; als unmittelbare, notwendige Abwehrbewegung tritt da eine Handlung auf. Beim Traumleben ist es etwas anders; es kommt nicht zu einer Handlung, aber mit einer ebenso unmittelbaren Notwendigkeit treten Bilder in unseren Seelenhorizont hinein. Aber so wenig, wie wir im wachen Tagesleben einen Überlegungseinfluß haben auf die Handbewegung, die wir machen, wenn sich eine Fliege auf unsere Hand setzt, ebensowenig haben wir einen Einfluß auf die chaotisch in uns auf- und abwogenden Traumbilder. Daher können wir sagen: Wenn wir einen Menschen im wachen Tagesleben erblikken und absehen von alle dem, was in ihm vorgeht, wenn wir nur seine Reflexbewegungen betrachten, alle Gesten und physiognomischen Ausdrücke, die er nur auf äußere Eindrücke hin, also ohne Überlegung vollbringt, so haben wir da eine Summe von solchen Handlungen vor uns, die aus Notwendigkeit beim Menschen eintreten. Erblicken wir dagegen einen träumenden Menschen, so sehen wir eine Summe von Bildern in das Wesen des Menschen hineinwirken, die jetzt nicht zu Handlungen führen, sondern nur Bildcharakter haben. Wie im wachen Tagesleben die ohne Überlegungen vor sich gehenden Handlungen des Menschen sich vollziehen, so erscheint im Menschen die Bilderwelt der chaotisch ineinanderwogenden Traumvorstellungen.

Wenn wir nun hinblicken auf unser Gehirn und es auch ansehen wollen als ein Werkzeug des Traumbewußtseins, was müssen wir da tun? Wir müssen uns denken, daß in diesem Gehirn etwas drinnen ist, was sich in gewisser Weise ähnlich benimmt wie unser Rückenmark, das zu den unbewußtten Handlungen führt. Wir haben ja das Gehirn zunächst anzusehen als Werkzeug des wachen Seelenlebens, wo wir unsere überlegten Vorstellungen schaffen. Wir müßten nun finden, wie den Traumvorstellungen gleichsam ein geheimnisvolles Rückenmark zugrundeliegt, das wie eingepreßt im Gehirn sitzt, das es aber nicht zu Handlungen bringt, sondern nur zu Bildern. Während unser Rückenmark es zu Handlungen bringt, wenn sie auch nicht durch Überlegung zustande kommen, bringt es das Gehirn in diesem Falle bloß zu Bildern. Es bleibt gewissermaßen auf halbem Wege stehen; es ist etwas im Gehirn wie eine geheimnisvolle Unterlage für eine unbewußte Seelentätigkeit, das wie eine Art Einschiebsel mit dem Charakter des Rückenmarks sich vorstellen läßt. Könnten wir also nicht sagen: Die Traumwelt führt uns in merkwürdiger Weise dazu, geheimnisvoll hindeuten zu können auf jenes alte Rükkenmark, das einst dem Gehirn zugrundelag? — Wenn wir unser Gehirn betrachten, wie es heute ausgebildet ist als Werkzeug des wachen Tageslebens, so ist es uns so bekannt, wie es erscheint, wenn wir es aus der Schädelhöhle herausnehmen. Aber es muß etwas darinnen eingeschlossen sein, das auftritt, wenn das wache Tagesleben ausgelöscht ist. Und das zeigt die okkulte Betrachtung, daß in dem Gehirn ein geheimnisvolles Rückenmark darinnen ist als das Werkzeug des Traumlebens (siehe Zeichnung S. 24, schraffiert).

Wenn wir es uns schematisch zeichnen wollen, könnten wir es so darstellen, daß in dem Gehirn der Vorstellungswelt des wachen Tageslebens ein für die äußere Wahrnehmung unsichtbares geheimnisvolles altes Rückenmark liegt, das irgendwie da hineingeheimnißt ist. Ich will es zunächst ganz hypothetisch aussprechen, daß dieses Rückenmark dann in Tätigkeit kommt, wenn der Mensch schläft und träumt, und dann so tätig ist, wie es sich für ein Rückenmark schickt, nämlich so, daß es mit Notwendigkeit seine Wirkungen hervorbringt. Aber weil es eingepreßt ist in das Gehirn, führt es nicht zu Handlungen, sondern zu bloßen Bildern, zu Bildhandlungen; denn wir handeln ja im Traume nur in Bildern. So hätten wir auch aus diesern eigentümlichen, sonderbaren chaotischen Leben heraus, das wir im Traume führen, Hinweise darauf, daß unserem Werkzeug des wachen Tageslebens, als welches wir mit Recht unser Gehirn betrachten, ein geheimnisvolles Organ zugrundeliegt, das vielleicht eine ältere Bildung ist, aus der es sich herausentwickelt hat. Wenn die Neubildung, das heutige Gehirn, schweigt, dann zeigt sich das, was das Gehirn einmal war; da zaubert dieses alte Rückenmark das heraus, was es kann. Aber weil es eingeschlossen ist, bringt es dieses alte Rückenmark nicht zu Handlungen, sondern bloß zu Bildern.

So also trennt uns die Betrachtung des Lebens selbst das Gehirn in zwei Stufen. Die Tatsache, daß wir träumen können, weist darauf hin, daß das Gehirn eine Entwicklung durchgemacht hat, in der es noch auf der Stufe des heutigen Rückenmarks stand, bevor es sich entwickelt hat zum Werkzeug des wachen Tageslebens. Wenn aber das wache Tagesleben schweigt, dann macht sich das alte Organ noch geltend.

So haben wir durch das bisher Gesagte schon etwas Typisches gewonnen, das sich durch eine äußere Betrachtung der Formen schon nachweisen läßt: Das wache Tagesleben verhält sich zum Traumleben wie das ausgebildete Gehirn zum Rückenmark. Wenn wir nun fortschreiten zu einer seherischen Betrachtung, können wir zu dem, was uns die Formbetrachtung geben kann, etwas hinzufügen. In welcher Weise das okkulte Schauen, das seherische Auge als Unterlage dienen kann für die ganz wesenhafte Betrachtung der menschlichen Natur und auf welche okkulte Forschung sich die Anschauungen über die im Schädel und in der Wirbelsäule eingeschlossenen Organe stützen, werden wir später noch sehen.

Nun wissen wir ja aus früheren Betrachtungen, daß des Menschen sichtbarer Leib nur ein Teil der gesamten Wesenheit des Menschen ist. In dem Augenblick, wo sich das hellseherische Auge öffnet, macht man die Erfahrung, daß dieser physische Leib sich eingeschlossen, eingebettet zeigt in einen übersinnlichen Organismus, in das, was man, grob gesprochen, die menschliche Aura nennt. Es wird dies hier zunächst wie eine Tatsache angeführt, und wir werden später darauf zurückkommen, inwiefern sie sich rechtfertigen läßt. Diese menschliche Aura, in welcher der physische Mensch nur wie ein Kern drinnen ist, zeigt sich für das seherische Auge als ein Farbengebilde, in dem verschiedene Farben auf- und abfluten. Man darf sich aber nicht vorstellen, daß man diese Aura malen könnte. Man kann sie nicht mit gewöhnlichen Farben wiedergeben, denn die Farben der Aura sind in fortwährender Bewegung, in fortwährendem Entstehen und Vergehen begriffen. Jedes Bild, das man von ihr malen wollte, könnte nur annähernd richtig sein, so wie auch niemand einen Blitz richtig malen kann, es würde nur ein starres Gebilde werden. Wie man den Blitz nicht richtig malen kann, so kann man das noch weniger bei der Aura, denn die aurischen Farben sind ungemein labil und beweglich, sie entstehen und vergehen fortwährend.

Nun ziehen sich die aurischen Farben in merkwürdigster Weise verschieden über den ganzen menschlichen Organismus hin; und es ist interessant, auf das aurische Bild hinzuweisen, das sich für das hellseherische Auge ergibt, wenn wir Schädeldecke und Rückgrat von rückwärts betrachten. Wenn wir uns den Teil der Aura vorstellen — von rückwärts betrachtet —, in den Schädel und Rückgrat, also Gehirn und Rückenmark, eingebettet sind, so zeigt sich, daß wir für den Teil der Aura, der zu den unteren Partien des Rückenmarks gehört, eine besonders deutliche Grundfarbe angeben können: er zeigt sich grünlich. Und wir können wiederum eine deutliche Farbe angeben, die in ihrer Art in keinem anderen Teile des Körpers zutage tritt, für die oberen Partien des Kopfes, wo das Gehirn ist: es ist eine Art Violettblau. Diese Farbe legt sich gleich einer Kappe oder einem Helm von rückwärts nach vorne über den Schädel.

Unterhalb der violettblauen Partien sieht man in der Regel eine Nuance, von der Sie sich am ehesten eine Vorstellung machen können, wenn Sie sie mit der Farbe einer jungen Pfirsichblüte vergleichen. Zwischen dieser Farbe und der grünlichen Farbe der unteren Teile des Rückgrats haben wir im mittleren Teil des Rückens andere, unbestimmte Farbnuancen, die außerordentlich schwer zu beschreiben sind, weil sie unter den gewöhnlichen, uns aus unserer sinnlichen Umwelt bekannten Farben nicht vorkommen. So schließt sich an das Grün eine Farbe an, die nicht grün, nicht blau und nicht gelb ist, sondern wie ein Gemisch von allen dreien; es zeigen sich Farben zwischen Gehirn und Rückgratende, die es im Grunde genommen innerhalb der physisch-sinnlichen Welt überhaupt nicht gibt. Wenn das nun auch schwierig zu beschreiben ist, so ist doch eines mit Bestimmtheit zu sagen, daß wir oben bei jenem sozusagen aufgeblasenen Rückenmark ein Violettblau haben und, hinuntergehend zum Ende des Rückgrates, zu einem deutlich grünlichen Farbton kommen.

Wir haben also heute an eine rein äußere Betrachtung der menschlichen Gestalt einige Tatsachen angeknüpft, die nur die hellseherische Forschung lehrt. Morgen soll nun versucht werden, auch die anderen Teile des physischen Menschenleibes, die sich an die bereits besprochenen angliedern, in ihrer Zweiheit zu betrachten, damit wir dann weiter vorgehen können und sehen, wie die ganze menschliche Wesenheit sich uns darstellt.

First Lecture

In this series of lectures, which is being held at the request of our friends in Prague, we will address a topic that is extremely close to people's hearts because it touches directly on the very essence of human beings and deals with what relates to their physical life itself. Although this topic is so close to human beings because it concerns them directly, it must also be said that it is very difficult to grasp. For even a glance at the demand that has been made of human beings throughout the ages, one might say from mystical and occult heights, “Know thyself,” shows us that self-knowledge, real, true self-knowledge, is basically quite difficult for human beings, and this applies not only to individual, personal self-knowledge, but above all to the knowledge of human nature in general. And because human beings—as can be seen from this eternal demand to “know thyself”—are so far removed from their own nature, have such a long way to go to understand themselves, what will be the subject of the following reflections in the coming days will, in a certain sense, appear to be something distant, requiring a great deal of different things in order to be understood. It was not without reason that I myself waited a long time and gave it careful consideration before deciding to speak about this topic. For it is a topic which, if one is to arrive at a true and genuine understanding, requires something that is so often overlooked in ordinary scientific observation: It is necessary to have reverence for the essence of human beings in general—mind you, not for the essence of individual human beings, especially not when that individual human being is ourselves—before we can consider the essence of human beings. And it must be regarded as a basic condition for our following considerations that we have reverence for what the human essence truly means.

How can one have true reverence for this? In no other way than by first disregarding how human beings — whether ourselves or others — appear to us in everyday life, and by rising to the view that This human being, with his entire development, is not here for his own sake; he is here to reveal the spirit, the entire world of the divine-spiritual; he is a revelation of the world deity, of the world spirit. And for those who recognize that everything around us is an expression of divine-spiritual forces, it is also possible to feel this reverence, not only for the divine-spiritual itself, but also for the revelations of this divine-spiritual. And when we speak of man striving for ever more perfect self-knowledge, we must be clear that it is not mere curiosity, or even a thirst for knowledge for its own sake, that should prompt us to strive for self-knowledge, but that we must feel it our duty to make the knowledge of the revelations of the world spirit through man ever more perfect. In this sense, the words must be understood: to remain ignorant where knowledge is possible is a sin against the divine destiny of man. For the world spirit has placed within us the power to become knowledgeable; and if we do not want to become knowledgeable, we reject—which we should not do—being a revelation of the world spirit, and we increasingly represent not a revelation of the world spirit, but a caricature, a distorted image of it. It is our duty to strive for knowledge in order to become more and more an image of the world spirit. Only when we can connect a meaning with these words, “to become an image of the world spirit,” only when it becomes meaningful to us to say in this sense: We must recognize that it is our duty to recognize — only then can we truly feel the sense of reverence toward the essence of the human being that was demanded earlier. And for those who, in the occult sense, want to consider the life of the human being, the essence of the human being, this permeation with reverence for human nature is an absolute necessity, because this permeation with reverence is the only thing capable of awakening our spiritual eyes and ears, our entire spiritual vision, that is, those forces that allow us to penetrate the spiritual foundations of human nature. Anyone who, as a seer, as a spiritual researcher, cannot have the highest degree of reverence for human nature, who cannot penetrate to the innermost fibers of his soul with a feeling of reverence for human nature, the image of the spirit, would remain blind, even if his eyes were wide open to this or that spiritual mystery of the world, to everything that relates to the deeper essence of the human being himself. And there may be many clairvoyants who can see this or that in the spiritual sphere of our existence: if they lack this reverence, then they lack the ability to look into the depths of human nature, and they will have nothing true to say about what constitutes the essence of the human being.

The study of human life processes is called “physiology.” This teaching is not to be considered here in the way it is in external science, but as it presents itself to the spiritual eye, so that we always look from the external forms of the human being, from the form and life processes of his organs, to the spiritual, supersensible foundation of the organs, the life forms, the life processes. And since it is not our intention to pursue this “occult physiology,” as one might call it, in any unscientific way, it will be necessary to make references in a certain unbiased manner to things that will sound rather improbable to the more or less uninitiated at first. It must be expressly emphasized that this series of lectures, even more than many others I have given, forms a whole, and that individual lectures, especially the introductory ones, cannot be judged out of context, because some things will have to be said in an unbiased manner. Only after hearing the final lectures will it be possible to form an opinion about what is actually being said. For the subject is being treated here in a somewhat different way than in external physiology. The initial principles will also be confirmed by what we will encounter at the end. We will not, so to speak, have to describe a straight line from beginning to end, but will proceed in a circle so that we arrive back where we started.

What is presented here is an observation of the human being. At first, this human being appears to us through the external senses in his external form. We know that today, in addition to what can be known about the human being through pure external, lay observation, there is a great deal that science has discovered. Therefore, we must necessarily compile what we can know about human beings today in an external way, from external experience and observation, from what the layman is already able to observe in himself and in other human beings, and from what science has succeeded in researching, which, through admirable methods and instruments, has arrived at its results about the physicality of human beings.

If we take together everything that we as laymen can see in the human being from a purely external point of view, everything that we may already have learned from popular descriptions, then it will perhaps not be incomprehensible when it is pointed out that even the external form of the human being, as it appears to us in the external world, consists of a duality. For those who want to penetrate the depths of human nature, it is absolutely necessary to become aware that even the outer human being, in terms of its form and structure, is basically a duality.

The one thing we can clearly distinguish in human beings is everything that is enclosed in organs that provide the greatest possible protection against the outside world. It is everything we can count as belonging to the brain and spinal cord. Everything that belongs to human nature in this respect, to the brain and spinal cord, is firmly enclosed by secure, protective bone structures. If we want to schematically represent what belongs to these two areas, we can illustrate this as follows: If a (see drawing) schematically represents the sum of the vertebrae stacked on top of each other, which run along the spinal cord, and b represents the skull cap and the bones of the skull, then everything that belongs to the brain and spinal cord is enclosed within the canal formed by the stacked vertebrae and the bones of the skull. One cannot look at a human being without realizing that everything that belongs in this area basically forms a self-contained whole and that everything else in the human body that we can physiologically classify in various ways—the neck, torso, and limbs—is connected to the brain and spinal cord by, figuratively speaking, more or less thread-like or ribbon-like structures. These must first break through the protective shell before a connection can be established with the part enclosed within these bone structures. Thus we can say that even a superficial observation reveals that everything in the human being is dual in nature; one part lies within the characteristic bone structures in firm and secure protective shells, the other outside them.

Now we must first take a very superficial look at what lies within these bone structures. Here we can again easily distinguish between the large mass embedded in the skull bones as the brain, and the other part, which hangs from it like a stem or strand, which is organically connected to the brain and extends into the spinal canal like a kind of thread-like outgrowth of the brain, the spinal cord. When we distinguish these two structures from each other, we must draw attention to something that external science does not need to draw attention to, but which occult science, which has to penetrate into the depths of the nature of things, must draw attention to. It must be pointed out that everything we say on the basis of a consideration of the human being initially refers only to the human being. For the moment we penetrate into the deeper causes of the individual organs, we become aware — we shall see in the course of these lectures that this is so — that an organ can have a completely different function in its deeper meaning in the human being than a similar or identical organ in the animal world. Those who view things from the perspective of ordinary external science will say: What you have told us here can also be said in relation to mammals. But what is said about the significance of organs in relation to humans cannot, if one delves deeper into the matter, be said in the same way for animals. Occult science has the task of considering animals for themselves and seeing whether what can be said about humans in relation to the spinal cord and brain also applies to animals. For the fact that animals closely related to humans also have spinal cord and brain does not prove that these organs have the same functions for humans and animals, just as, to use a comparison, one can hold a knife in one's hand in order to carve a calf or to erase something. In both cases, one is dealing with a knife, and anyone who only considers the form of the knife will believe that it is the same thing in both cases. The same would be true of someone who believes that because humans and animals have the same organs, the brain and spinal cord, these must serve the same purpose. But that is not true. This is something that has become common practice in external science and has led to certain inaccuracies, and it can only be corrected when external science deigns to gradually address what can be said about the characters of beings from the depths of supersensible research.