An Occult Physiology

GA 128

21 March 1911, Prague

2. Human Duality

We shall encounter again and again, in the course of our reflections, the difficulty of keeping in our mind's eye ever more exactly the exterior organism of man, in order that we may learn to know the transitory, the perishable. But we shall also see that this very road will lead us to a knowledge of the imperishable, the eternal in human nature. Also it will be necessary, in order to attain this goal, to sustain the effort of looking upon the exterior human organism in all reverence, as a revelation of the spiritual world.

When once we have permeated ourselves in some measure with spiritual-scientific concepts and feelings, we shall come quite easily to the thought that the human organism in its stupendous complexity must be the most significant expression, the greatest and most important manifestation, of those forces which live and weave as Spirit throughout the world. We shall, indeed, have to find our way upward ever more and more from the outer to the inner.

We have already seen that external observations, both from the point of view of the layman and from that of the scientific inquirer, must lead us to look upon man in a certain sense as a duality. We have characterised this duality of the human being—only hastily yesterday, to be sure, for we shall have to go into this still more accurately—as being enclosed within the protecting bony sheath of the skull and the spinal vertebrae. We have seen that, if we ascend beyond the exterior form of this part of man, we may gain a preliminary view of the connection between the life which we call our waking life of day, and that other life, in the first place very full of uncertainty for us, which we call the life of dreams. And we have seen that the external forms of that portion of human nature which we have described give us a kind of image, signify in a way a revelation, on the one hand of dream-life, the chaotic life of pictures; and on the other hand the waking day life, which is endowed with the capacity to observe in sharp outlines.

To-day we shall first cast a fleeting glance over that part of the human duality which may be found outside the region we had in mind yesterday. Even the most superficial glance over this second portion of the human being can teach us that this portion really presents a picture in a certain respect the opposite of the other one. In the brain and the spinal cord we have the bony formation as the outer circumference, the covering. If we consider the other portion of man's nature, we are surely obliged to say that here we have the bony formation disposed rather more within the organs. And yet this would be only a very superficial observation. We shall be carried deeper into the construction of this other portion of man's nature if, for the moment, we keep the most important systems of organs apart one from another, and compare them, first, outwardly, with what we learned yesterday.

The systems of organs, or systems of instruments, of the human organism to be considered first in this connection, must be the apparatus of nutrition and all that lies between this apparatus and that wonderful structure the heart, which we readily experience as a sort of central point of the whole human organism... And here even a superficial glance shows us at once that these systems of instruments, especially the apparatus of nutrition as we may call it in everyday speech, are intended to take in the substances of our external, earthly world and prepare them for further digestive work in the physical organism of man. We know that this apparatus of digestion begins by extending downward from the mouth, in the form of a tube, to the organ which everyone knows as the stomach. And a superficial observation teaches us that, from those articles of food which are conveyed through this canal into the stomach, the portions which are to a certain extent unassimilated are simply excreted, whereas other portions are carried over by the remaining digestive organs into the organism of the human body.

It is also well known that, adjoining the actual digestive apparatus in the narrower sense of the term, and for the purpose of taking over from it in a transformed condition the nutritive substances with which it has been supplied, is what we may call the lymph-system. I shall at this point speak merely in outline. We may repeat accordingly that, adjoining the apparatus of nutrition in so far as this is attached chiefly to the stomach, there is this system of organs called the lymph-system, consisting of a number of canals, which in their turn spread over the whole body; and that this system takes over, in a certain way, what has been worked over by the rest of the digestive apparatus, and delivers it into the blood.

And then we have the third of these systems of organs, the blood-vessel system itself, with its larger and smaller tubes extending throughout the entire human organism and having the heart as the central point of all its work. We know also that, going out from the heart, those blood-vessels or blood-filled vessels which are called arteries, convey the blood to all parts of our organism; that the blood goes through a certain process in the separate parts of the human organism, and then is carried back to the heart by means of other similar vessels which bring it back, however, in a transformed condition as so called “blue blood” in contrast to its red state. We know that this transformed blood, no longer useful for our life, is conducted from the heart into the lungs; that it there comes into contact with the oxygen taken up from the outer air; and that, by means of this, it is renewed in the lungs and conducted back again to the heart, to go its way afresh throughout the whole human organism.

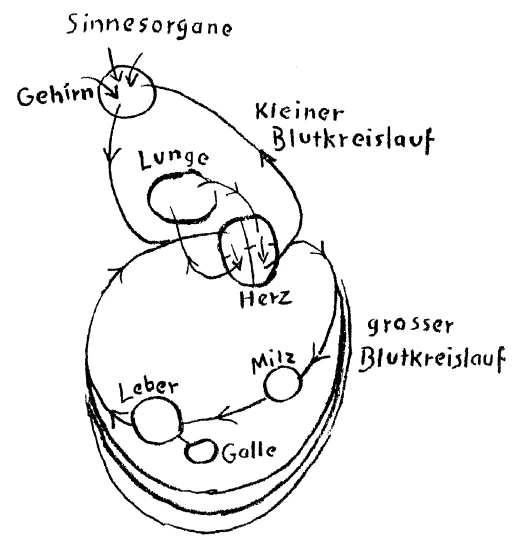

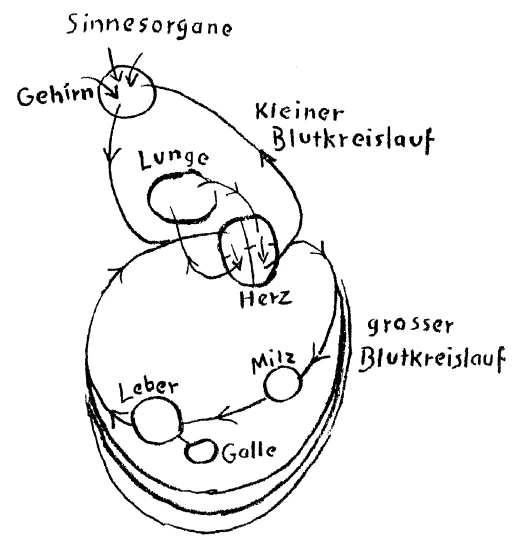

If we are to consider these systems in their completeness, in order to have in our external method of observation a foundation for the occult method, let us begin by holding to that system which must, at the very outset, obviously be for everyone the central system of the entire human organism, namely, the blood-and-heart system. Let us, moreover, keep in mind that after the stale blood has been freshened in the lungs, transformed from blue blood into red blood, it returns once more to the heart and then goes out again from the heart as red blood, to be used in the organism. Notice, that everything which I intend to draw will be in mere outline, so that we shall be dealing only with sketches.

Let us now briefly recall that the human heart is an organ which, properly speaking, consists in the first place of four parts or chambers, so separated by interior walls that one can distinguish between the two larger spaces lying below and the two smaller ones lying above, the two lower ones being the ventricles, as they are generally called, and the two upper ones the auricles. I shall not speak about the “valves” to-day, but shall rather call attention, quite sketchily, to the course of the most important organic activities. And here, to begin with, one thing is clear: after the blood has streamed out of the left auricle into the left ventricle, it flows off through a large artery and from this point is conducted through the entire remainder of the organism. Now, let us bear in mind that this blood is first distributed to every separate organ of the whole organism; that it is then used up in this organism so that it is changed into the so-called blue blood, and as such returns to the right auricle of the heart; and that from there it flows into the right ventricle in order that it may go out again from this into the lungs, there again to be renewed and take a fresh course throughout the organism.

When we begin to visualise all this it is important, as a basis for an occult method of study, that we also add the fact that what we may call a subsidiary stream branches out from the aorta very near the heart; that this subsidiary stream leads to the brain, thus providing for the upper organs, and from there leads back again in the form of stale blood into the right auricle; and that it is there transformed, as blood which has passed through the brain, so to speak, in the same way as that blood is transformed which comes from the remaining members of the organism. Thus we have a smaller, subsidiary circuit of the blood, in which the brain is inserted, separate from the other main circuit which provides for the entire remaining organism. Now, it is of extraordinary importance for us to bear this fact in mind. For we can only arrive at an important conception, affording us a basis for everything that will enable us to ascend to occult heights, if at this point we first ask ourselves the following question: In the same way in which the upper organs are inserted in the smaller circuit, is there something similar inserted within the circuit of the blood which provides for the rest of the organism. Here we come, as a matter of fact, to a conclusion which even the external, superficial method of study can supply, that is, that there is inserted in the large circuit of the blood the organ we call the spleen; that further on is inserted the liver; and, still further on, the organ which contains the gall prepared by the liver.

Now, when we ask about the functions of these organs, external science answers by saying that the liver prepares the gall; that the gall flows out into the digestive canal, and takes part in digesting the food in such a way that this may then be taken up by the lymph-system and conducted over into the blood. Much less, however, does external science tell us with regard to the spleen, the third of the organs here considered as inserted in the main circuit. When we reflect upon these organs, we must first give attention to the fact that they have to occupy themselves with the preparation of the nutritive matter for the human organism; but that, on the other hand, they are all three inserted as organs into the circulatory course of the blood. It is not without reason that they are thus inserted, for, in so far as nutritive matter is taken up into the blood, to be conveyed by means of the blood to the human organism in order to continuously supply this with substances for its up-building, these three organs take part in the whole process of working over this nutritive matter.

Now arises the question: Can we already draw some sort of conclusion, from an external aspect, as to just how these organs take part in the joint activity of the human organism? Let us first fix our attention on this one external fact, namely, that these organs are inserted into the lower circulatory course of the blood in the same way in which the brain is inserted into the upper course; and let us now see for a moment, while first actually holding to this external method of study, which must later be deepened, whether it is possible that these organs really have a task similar to that of the brain. At the same time, wherein may such a task consist?

Let us begin by considering the upper portions of the human organism. It is these that receive the sense-impressions through the organs of sense, and work over the material contained in our sense-perceptions. We may say, therefore, that what takes place in the human head, in the upper part of the organism, is a working over of those impressions which flow in from outside through the sense-organs; and that what we may describe as the cause of everything that takes place in these upper parts is to be found in its essence in the external impressions or imprints. And, since these external impressions send their influences, together with what results from these influences in the working over of the outer impressions, into the upper organs of the organism, they therefore change the blood, or contribute to its change, and in their own way send this blood back to the heart transformed, just as the blood is sent back to the heart transformed from the rest of the organism.

Is it not obvious that we should now ask ourselves this other question: Since this upper part of the human organism opens outward by means of the sense-organs, opens doors to the outside world in the form of sense- organs, is there not a certain sort of correspondence between the working-in of the external world through these sense-organs upon the upper part of the human organism and that which works out of the three interior organs, the spleen, the liver, and the gall-bladder? Whereas, accordingly, the upper part of the organism opens outward in order to receive the influences of the outside world; and whereas the blood flows upwards, so to speak, in order to capture these impressions of the outside world, it flows downwards in order to take up what comes from these three organs. Thus we may say that, when we look out upon the world round about us, this world exercises its influence through our senses upon our upper organisation. And what thus flows in from outside, through the world of sense, we may think of as pressed together, contracted, as if into one centre; so that what flows into our organism from all sides is seen to be the same thing as that which flows out from the liver, the gall-bladder and the spleen, namely, transformed outside world. If you go further into this matter you will see that it is not such a very strange reflection.

Imagine to yourselves the different sense-impressions that stream into us; imagine these contracted, thickened or condensed, formed into organs and placed inside us. Thus the blood presents itself inwardly to the liver, gallbladder and spleen, in the same way as the upper part of the human organism presents itself to the outside world. And so we have the outside world which surrounds our sense-organs above, condensed as it were into organs that are placed in the interior of man, so that we may say: At one moment the world is working from outside, streaming into us, coming into contact with our blood in the upper organs, acting upon our blood; and the next moment that which is in the macrocosm works mysteriously in those organs into which it has first contracted itself, and there, from the opposite direction, acts upon our blood, presenting itself again in the same way as it does in the upper organs.

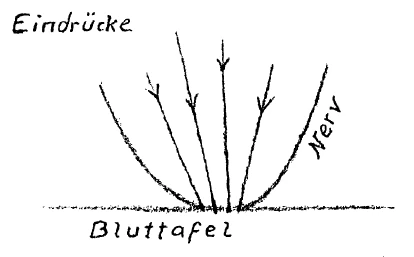

If we were to draw a sketch of this, we could do it by imagining the world on the one hand, acting from all directions upon our senses, and the blood exposing itself like a tablet to the impressions of this world; that would be our upper organism. And now let us imagine that we could contract this whole outer world into single organs, thus forming an extract of this world; that we could then transfer this extract into our interior in such a way that what is working from all directions now acts upon the blood from the other side of the tablet. We should then have formed in a most extraordinary way a pictorial scheme of the exterior and the interior of the human organism. And we might already to a certain extent be able to say that the brain actually corresponds to our inner organism, in so far as this latter occupies the breast and the abdominal cavity. The world has, as it were been placed in our inner man.

Even in this organisation, which we distinguish as a subordinate one, and which serves primarily for the carrying forward of the process of nutrition, we have something so mysterious as the fusion of the whole outer cosmos into a number of inner organs, inner instruments. And, if we now observe these organs more closely for a moment, the liver, the gall-bladder, and the spleen, we shall be able to say that the spleen is the first of these to offer itself to the blood-stream. This spleen is a strange organisation, embedded in plethoric tissue, and in this tissue there is a great number of tiny little granules—something which, in contrast to the rest of the mass of tissue, has the appearance of little white granules.

When we observe the relation between the blood and the spleen, the latter appears to us like a sieve through which the blood passes in order that it may offer itself to an organ of the kind which, in a certain sense, is a shrivelled-up portion of the macrocosm. Again, the spleen stands in connection with the liver. At the next stage we see how the blood offers itself to the liver, and how the liver in its turn, as a third step, secretes the gall, which then goes over into the nutritive substances, and from there comes with the transformed nutritive substances into the blood.

This offering of itself on the part of the blood to these three organs we cannot think of in any but the following way: The organ which first meets the blood is the spleen, the second is the liver, and the third is the gallbladder, which has really a very complicated relation to the entire blood system, in that the gall is given over to the food and takes part in its digestion. On such grounds, the occultists of all times have given certain names to these organs. Now, I beg of you most earnestly not to think of anything special for the time being in connection with these names, but rather to think of them only as names that were originally given to these organs and to disregard the fact that the names signify also something else in connection with these organs. Later on we shall see why just these names were chosen. Because the spleen is the first of the three organs to present itself to the blood—we can say this by way of a purely external comparison—it appeared to the occultists of old to be best designated by the name belonging to that star which, to these ancient occultists and their observations, was the first within our solar system to show itself in cosmic space. For this reason they called the spleen “saturnine,” or an inner Saturn in man; and, similarly, the liver they called an inner Jupiter; and the gallbladder, an inner Mars. Let us begin by thinking of nothing in connection with these names, except that we have chosen them because we have arrived at the concept, at first hypothetical, that the external worlds, which otherwise are accessible rather to our senses, have been contracted into these organs and that in these organs inner worlds, so to speak, come to meet us, just as outer worlds meet us in the planets. We may now be able to say that, just as the external worlds show themselves to our senses in that they press in upon us from outside, so do these inner worlds show themselves as acting upon the blood-system in that they influence that for which the blood-system is there.

We shall find, to be sure, a significant difference between what we spoke of yesterday as the peculiarities of the human brain and that which here appears to us as a sort of inner cosmic system. This difference lies simply in the fact that man, to begin with, knows nothing about what takes place within his lower organism: that is, he knows nothing about the impressions which the inner worlds, or planets, as we may call them, make upon him, whereas the very characteristic of the other experience is that the outer worlds do make their impressions upon his consciousness. In a certain respect, therefore, we may call these inner worlds the realm of the unconscious, in contrast to the conscious realm we have learned to know in the life of the brain.

Now, precisely that which lies in this “conscious” and this “unconscious” is more clearly explained when we employ something else to assist us. We all know that external science states that the organ of consciousness is the nerve-system, together with all that pertains to it. Now we must bear in mind, as a basis for our occult study, a certain relationship which the nerve-system has to the blood-system, that is, to what we have to-day considered in a sketchy way. We then see that our nerve-system everywhere enters in certain ways into relation with our blood-system, that the blood everywhere presses upon our nerve-system. Moreover, we must here first take notice of something which external science in this connection holds to be already established. This science looks upon it as a settled matter that in the nerve-system is to be found the sole and entire regulator of all activity of consciousness, of everything, that is, which we characterise as “soul-life.” We cannot here refrain from recalling, although at first only by way of allusion for the purpose of authenticating this later on, that for the occultist the nerve-system exists only as a sort of basis for consciousness. For precisely in the same way that the nerve-system is a part of our organism and comes into contact with the blood-system, or at least bears a certain relation to it, so do the ego and that which we call the astral body make themselves a part of the whole human being. And even an external observation, which has frequently been employed in my lectures, can show us that the nerve-system is in a certain way a manifestation of the astral body. Through such an observation we can see that, in the case of ordinary inanimate beings in nature, we can ascribe only a physical body to that part of their being which they present to us. When, however, we ascend from inanimate, inorganic natural bodies to animate natural bodies, to organisms, we are obliged to suppose that these organisms are permeated by the so-called ether-body, or life-body, which contains in itself the causes of the phenomena of life. We shall see later on that anthroposophy, or occultism, does not speak of the ether-body, or life-body, in the same way that people in the past spoke of “life-force.” Rather does anthroposophy, when it speaks of the ether-body, speak of some thing which the spiritual eye actually sees, that is, of something real underlying the external physical body. When we consider the plants we are obliged to attribute to them an ether-body. And, if we ascend from the plants to sentient beings, to the animals, we find that it is this element of sentiency, of inner life, or, better still, of inner experience, which primarily differentiates the animal externally from the plant. If mere life-activity, which cannot yet sense itself inwardly, cannot yet attain to the kindling of feeling, is to be able to kindle feeling, to sense life inwardly, the astral body must become a part of the animal's organism. And in the nerve-system, which the plants do not yet have, we must recognise the external instrument of the astral body, which in turn is the spiritual prototype of the nerve-system. As the archetype is related to its manifestation, to its image, so is the astral body related to the nerve-system.

Now when we come to man—and I said yesterday that in occultism our task is not as simple as it is for the external scientific method in which everything can, so to speak, be jumbled together—we must always, when we study the human organs, be aware of the fact that these organs, or systems of organs, are capable of being put to certain uses for which the corresponding systems of organs in the animal organism, even when these appear similar, cannot be used. At this point we shall merely affirm in advance what will appear later as having a still more profound basis, that, in the case of man, we must designate the blood as an external instrument for the ego, for all that we denote as our innermost soul-centre, the ego; so that in the nerve-system we have an external instrument of the astral body, and in our blood an external instrument of the ego. Just as the nerve-system in our organism enters into certain relations with the blood, so do those inner regions of the soul which we experience in ourselves as concepts, feelings or sensations, etc., enter into a certain relation with our ego.

The nerve-system is differentiated in the human organism in manifold ways the inner nerve-fibres for example, at the points where these develop into nerves of hearing, of seeing, etc., show us how diverse are its differentiations. Thus the nerve-system is something that reaches out everywhere through the organism in such a way as to comprise the most manifold inner diversities. When we observe the blood as it streams through the organism it shows us, even taking into account the transformation from red into blue blood, that it is, nevertheless, a unity in the whole organism. Having this character of unity, it comes into contact with the differentiated nerve-system, just as does the ego with the differentiated soul-life, for it also is made up of conceptions, sensations, will-impulses, feelings and the like. The further you pursue this comparison—and it is given meanwhile only as a comparison—the more clearly you will be shown that a far-reaching similarity exists in the relations of the two archetypes, the ego and the astral body, to their respective images, the blood-system and the nerve-system. Now, of course, one may say at this point that blood is surely everywhere blood. At the same time, it undergoes a change in flowing through the organism; and consequently we can draw a parallel between these changes that take place in the blood and what goes on in the ego. But our ego is a unity. As far back as we can remember in our life between birth and death we can say: “This ego was always present, in our fifth year just as in our sixth year, yesterday just as to-day. It is the same ego.” And yet, if we now look into what this ego contains, we shall discover this fact: This ego that lives in me is filled with a sum-total of conceptions, sensations, feelings, etc., which are to be attributed to the astral body and which comes into contact with the ego. A year ago this ego was filled with a different content, yesterday it contained still another, and to-day its content is again different. Thus the ego, we see, comes into contact with the entire soul-content, streams through this entire soul-content. And, just as the blood streams through the whole organism and comes everywhere into contact with the differentiated nerve-system, so does the ego come together with the differentiated life of the soul, in conceptions, feelings, will-impulses and the like. Already, therefore, this merely comparative method of study shows us that there is a certain justification in looking upon the blood system as an image of the ego, and the nerve system as an image of the astral body, as higher, super-sensible members of the nature of man.

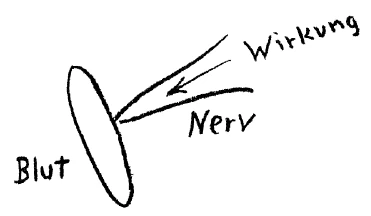

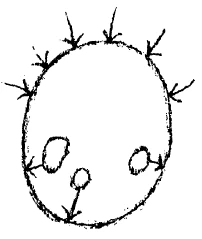

It is necessary for us to remember that the blood streams throughout the organism in the manner already indicated; that on the one side it presents itself to the outer world like a tablet facing the impressions of the outer world; on the other side, it faces what we have called the inner world. And so indeed it is with our ego also. We first direct this ego of ours toward the outside world and receive impressions from it. There results from this a great variety of content within the ego; it is filled with these impressions coming from outside. There are also such moments when the ego retires within itself and is given up to its pain and suffering, pleasure and happiness, inner feelings and so forth, when it permits to arise in the memory what it is not receiving at this moment directly through contact with the external world, but what it carries within itself. Thus, in this connection also, we find a parallel between the blood and the ego; for the blood, like a tablet, presents itself at one time to the outside world and at another time to the inner world; and we could accordingly represent this ego by a simple sketch [see earlier drawing] exactly as we have represented the blood. We can bring the external impressions which the ego receives, when we think of them as concepts, as soul-pictures in general, into the same sort of relation to the ego as that which we have brought about between our blood and the real external occurrences coming to us through the senses. That is, exactly as we have done in the case of the physical bodily life and the blood, so could we bring what is related to the soul-life into connection with the ego.

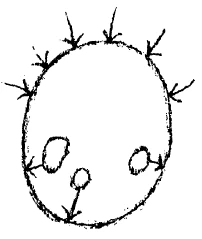

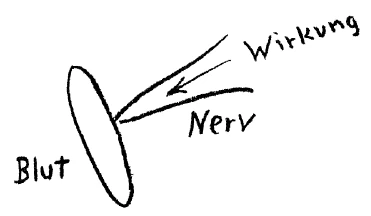

Let us now observe from this standpoint the cooperation, the mutual interaction, between the blood and the nerves. If we consider the eye, we see that outer impressions act upon this organ. The impressions of colour and light act upon the optic nerve. So long as they affect the optic nerve, having for themselves an active instrument in the nerve-system, we are able to affirm that they have an effect upon the astral body. We may state that, at the moment when a connection takes place between the nerves and the blood, the parallel process which takes place in the soul is, that the manifold conceptions within the life of the soul come into connection with the ego. When, therefore, we consider this relationship between the nerves and the blood, we may represent by another sketch how that which streams in from outside through the nerves when we see an object, forms a certain connection with those courses of the blood which come into the neighbourhood of the optic nerve.

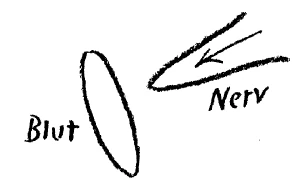

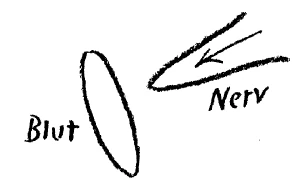

This connection is something of extraordinary importance for us, if we wish to observe the human organism in such a way that our observation shall provide a basis for arriving at the occult foundations of human nature. In ordinary life the process that takes place is such that each influence transmitted by means of the nerves inscribes itself in the blood, as on a tablet, and in doing so records itself in the instrument of the ego. Let us suppose for a moment, however, that we should artificially interrupt the connection between the nerve and the circulation of the blood, that is, that we should artificially put a man in such a condition that the activity of the nerve should be severed from the circulation of the blood, so that they could no longer act upon each other. We can indicate this by a diagram in which the two parts are shown more widely separated, so that a reciprocal action between the nerves and the blood can no longer take place. In this case the condition may be such that no impression can be made upon the nerve. Something of this sort can be brought about if, for example, the nerve is cut. If, indeed, it should come to pass by some means that no impression is made upon the nerve, then it is also not strange if the man himself is unable to experience anything especial through this nerve. But let us suppose that in spite of the interrupting of the connection between the nerve and the blood a certain impression is made upon the nerve. This can be brought to pass through an external experiment by stimulating the nerve by means of an electric current. Such external influence on the nerve does not, however, concern us here. But there is still another way of affecting the nerve under conditions in which it cannot act upon the course of the blood normally connected with it.

It is possible to bring about such a condition of the human organism; and this is done in a particular way, by means of certain concepts, emotions and feelings which the human being has experienced and made a part of himself, and which, if this inner experiment is to be truly successful, ought, properly speaking, to be really lofty, moral or intellectual concepts. When a man practises a rigorous inner concentration of the soul on such imaginative concepts, forming these into symbols let us say, it then happens, if he does this in a state of waking consciousness, that he takes complete control of the nerve and, as a result of this inner concentration, draws it back to a certain extent from the course of the blood. For when man simply gives himself up to normal, external impressions, the natural connection between the nerve and the circulation is present; but if, in strict concentration upon his ego, he holds fast to what he obtains in a normal way, apart from all external impressions and apart from what the outside world brings about in the ego, he then has something in his soul which can have originated only in the consciousness and is the content of consciousness, and which makes a special demand upon the nerve and separates its activity then and there from its connection with the activity of the blood. The consequence of this is that, by means of such inner concentration, which actually breaks the connection between the nerve and the blood, that is, when it is so strong that the nerve is in a certain sense freed from its connection with the blood-system, the nerve is at the same time freed from that for which the blood is the external instrument, namely, from the ordinary experiences of the ego. And it is, indeed, a fact—this finds its complete experimental support through the inner experiences of that spiritual training designed to lead upward into the higher worlds—that as a result of such concentration the entire nerve-system is removed from the blood-system and from its ordinary tasks in connection with the ego. It then happens, as the particular consequence of this, that whereas the nerve-system had previously written its action upon the tablet of the blood, it now permits what it contains within itself as working power to return into itself, and does not permit it to reach the blood. It is, therefore, possible purely through processes of inner concentration, to separate the blood-system from the nerve-system, and thereby to cause that which, pictorially expressed, would otherwise have flowed into the ego, to course back again into the nerve-system.

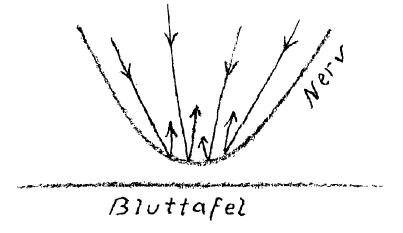

Now, the peculiar thing is that once the human being actually brings this about through such inward exertion of the soul, he has then an entirely different sort of inner experience. He stands before a completely changed horizon of consciousness which may be described somewhat as follows: When the nerve and the blood have an appropriate connection with each other, as is the case in normal life, man brings into relation with the ego the impressions which come from within his inner being and those which come from the outer world. The ego then conserves those forces which reach out along the entire horizon of consciousness, and everything is related to the ego. But when, through inner concentration, he separates his nerve-system, lifts it, that is to say, through inner soul-forces out of his blood-system, he does not then live in his ordinary ego. He cannot then say “I” with respect to that which he calls his “Self,” in the same sense in which he had previously said “I” in his ordinary normal consciousness. It then seems to the man as if he had quite consciously lifted a portion of his real being out of himself, as if something which he does not ordinarily see, which is super-sensible and works in upon his nerves, does not now impress itself upon his blood-tablet or make any impression upon his ordinary ego. He feels himself lifted away from the entire blood-system, raised up, as it were, out of his organism; and he meets something different as a substitute for what he has experienced in the blood-system. Whereas the nerve-activity was previously imaged in the blood-system, it is now reflected back into itself. He is now living in something different; he feels himself in another ego, another Self, which before this could at best be merely divined. He feels a super-sensible world uplifted within him.

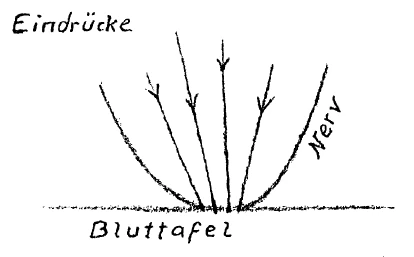

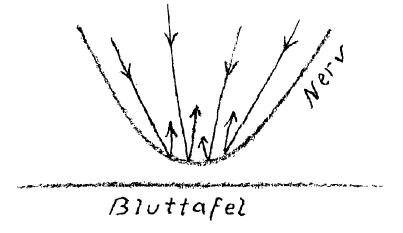

If once more we draw a sketch, showing the relation between the blood and the nerve, or the entire nerve-system, as this receives into itself the impressions from the outside world, this may be done in the following way.

The normal impressions would then image themselves in the blood-system, and thus be within it. If, however, we have removed the nerve-system, nothing goes as far as the tablet of the blood, nothing goes into the blood-system; everything flows back again into the nerve-system; and thus a world has opened to us of which we had previously no intimation. It has opened as far as the terminations of our nerve-system, and we feel the recoil. To be sure, only he can feel this recoil who goes through the necessary soul-exercises. In the case of the normal consciousness, man feels that he takes into himself whatever sort of world happens to face him, so that everything is inscribed upon the blood-system as on a tablet, and he then lives in his ego with these impressions. In the other case, however, he goes with these impressions only to that point where the terminations of the nerves offer him an inner resistance. Here, at the nerve-terminals, he rebounds as it were, and experiences himself in the outside world. Thus, when we have a colour impression, which we receive through the eye, it passes into the optic nerve, images itself upon the tablet of the blood, and we feel what we express as a fact when we say: “I see red.” But now, after we have made ourselves capable of doing so, let us suppose that we do not go with our impressions as far as the blood, but only to the terminations of the nerves; that at this point we rebound into our inner life, rebound before we reach the blood. In that case we live, as a matter of fact, only as far as our eye, our optic nerve. We recoil before the bodily expression of our blood, we live outside our Self and are actually within the light-rays which penetrate our eyes. Thus we have actually come out of ourselves; indeed, we have accomplished this by reason of the fact that we do not penetrate as deep down into our Self as we ordinarily do, but rather go only as far as the nerve-terminals. The effect on a soul-life such as this, if we have brought it to the stage where we turn back at the terminations of the nerves into our inner being, so that we do not go as far as our blood, is that we have in this case disconnected the blood; whereas otherwise the normal consciousness of the inner man ordinarily goes down into the blood, and the soul-life identifies itself with the physical man, feels itself at one with him.

As a result of these external observations we have to-day succeeded in disconnecting the entire blood-system, which we have thought of as a kind of tablet that presents itself on the one side to the external, on the other side to the internal impressions, from what we may call the higher man, the man we may become if we find release from our Selves and become free. Now, we shall best be able to study the whole inner nature of this blood-system if we do not make use of general phrases, but observe what exists as reality in man, namely, the super-sensible, invisible man to whom we can lift ourselves when we go only as far as the terminations of our nerves, and if we also observe man as he is when he goes all the way into the blood. For we can then advance further, to the thought that man can really live in the outside world, that he can pour himself out over the whole external world, can go forth into this world and view from the reverse standpoint, as it were, the inner man, or what is usually meant by that term. In short, we shall learn to know the functions of the blood, and of those organs which are inserted into the circulatory course of the blood, when we can answer the following questions: What does a more accurate knowledge show us, when that which comes from a higher world, to which man can raise himself, is portrayed upon the tablet of the blood? It shows us that everything connected with the life of the blood is the very central point of the human being, when, without coining phrases, but rather looking only at sensible as well as super-sensible realities, we consider carefully the relationship of this wonderful system to a higher world. For this is in truth to be our task: to learn to see clearly the whole visible physical Man as an image of that other “Man” who is rooted and lives in the spiritual world. We shall thereby come to find that the human organism is one of the truest images of that Spirit which lives in the universe, and we shall attain to a very special understanding of that Spirit.

Zweiter Vortrag

Wir werden zwar innerhalb dieser Betrachtungen immer wieder in die Schwierigkeit versetzt werden, den äußeren menschlichen Organismus genauer ins Auge zu fassen, um sozusagen das Vergängliche, das Zerbrechliche zu erkennen. Aber wir werden auch sehen, daß gerade dieser Weg uns führen wird zu einer Erkenntnis des Bleibenden, des Unvergänglichen, des Ewigen in der menschlichen Natur. Allerdings ist es notwendig, wenn unsere Betrachtungen dieses Ziel haben sollen, daß wir das streng einhalten, was gestern schon in der Einleitung bemerkt worden ist: den Gesichtspunkt, den äußeren physischen Organismus in aller Ehrfurcht als eine Offenbarung aus geistigen Welten zu betrachten.

Wenn wir uns schon einigermaßen mit geisteswissenschaftlichen Begriffen und Empfindungen durchdrungen haben, können wir uns ja sehr leicht in den Gedanken hineinfinden, daß der menschliche Organismus in seiner ungeheuren Kompliziertheit der bedeutsamste Ausdruck, die größte und bedeutendste Offenbarung der Kräfte sein muß, die als geistige Kräfte die Welt durchweben und durchleben. Wir werden allerdings sozusagen vom Äußeren immer mehr und mehr in das Innere aufzusteigen haben.

Wir haben gestern schon gesehen, wie uns die äußerliche Betrachtung sowohl des Laien als auch der Wissenschaft dazu führen muß, den Menschen gewissermaßen als eine Zweiheit anzusehen. Wir haben diese Zweiheit der menschlichen Wesenheit gestern schon flüchtig charakterisiert - wir werden darauf noch genauer einzugehen haben -, und wir haben dasjenige an der menschlichen Wesenheit genauer betrachtet, was eingeschlossen ist in die schützende Knochenhülle des Schädels und der Rückenwirbel. Dabei haben wir gesehen, wie wir, wenn wir ausgehen von der äußeren Gestaltung und Form dieses Teils des Menschen, schon einen vorläufigen Ausblick gewinnen können in den Zusammenhang desjenigen Lebens, das wir unser waches Tagesleben nennen, mit jenem anderen, zunächst für uns natürlich sehr von Zweifeln durchwobenen Leben, das wir das Traumleben nennen. Wir haben gesehen, daß schon die äußeren Formen des charakterisierten Teiles der Menschennatur eine Art Abbild geben, eine Art Offenbarung bedeuten: auf der einen Seite des Traumlebens, dieses chaotischen Bilderlebens, und auf der anderen Seite des mit scharf umrissener Beobachtung ausgestatteten wachen Tageslebens. Heute werden wir zunächst einen flüchtigen Blick zu werfen haben auf das andere Glied der menschlichen Zweiheit, das sich gewissermaßen außerhalb des Bereiches befindet, den wir gestern ins Auge gefaßt haben. Schon der alleroberflächlichste Blick auf diesen zweiten Teil der menschlichen Wesenheit kann uns darüber belehren, daß dieser in gewisser Beziehung das entgegengesetzte Bild dessen zeigt, was wir bei Gehirn und Rückenmark ins Auge gefaßt haben. Gehirn und Rückenmark sind von Knochenbildungen als schützender Hülle umschlossen. Betrachten wir den anderen Teil der menschlichen Natur, so müssen wir entschieden sagen, daß wir hier die Knochenbildung mehr in den Organismus hineingegliedert finden. Doch das wäre nur eine ganz oberflächliche Betrachtung. Tiefer hinein in das Gefüge dieses anderen Teiles der Menschennatur werden wir schon geführt, wenn wir die bedeutendsten Organsysteme auseinanderhalten und sie zunächst äußerlich vergleichen mit dem, was wir gestern kennengelernt haben.

Diejenigen Organsysteme, Werkzeugsysteme des menschlichen Organismus, welche dabei zuerst in Betracht kommen werden, sollen sein der Ernährungsapparat und alles das, was zwischen dem Ernährungsapparat und jenem wunderbaren Gebilde liegt, das wir unschwer wie eine Art Mittelpunkt der ganzen menschlichen Organisation empfinden können, dem Herzen. Da zeigt uns gleich der oberflächliche Blick, daß der Ernährungsapparat — wie man ihn im populären Sinne nennen kann — dazu bestimmt ist, die Stoffe unserer äußeren irdischen Umwelt aufzunehmen und für die weitere Verarbeitung im physischen Organismus des Menschen vorzubereiten. Wir wissen, daß dieser Verdauungsapparat zunächst von unserem Munde aus röhrenförmig zu dem Organ sich erstreckt, das jeder als den Magen kennt. Und schon eine oberflächliche Betrachtung lehrt uns, daß von jenen Nahrungsmitteln, die durch diesen Kanal in den Magen eingeführt werden, gewissermaßen unverwendete Teile einfach abgesondert werden, während andere Teile von den weiteren Verdauungsorganen in den menschlichen Leibesorganismus übergeführt werden. Es ist ja auch wohl bekannt, daß an den eigentlichen Verdauungsapparat im engeren Sinne sich das anschließt, was wir das Lymphsystem nennen - ich will jetzt zunächst nur schematisch sprechen -, um die vom Verdauungsapparat hineingelieferten Nahrungsstoffe in verwandeltem Zustande aufzunehmen. So daß wir sagen können, daß an den Verdauungsapparat, soweit er sich an den Magen angliedert, ein Organsystem sich anschließt, das Lymphsystem, als eine Summe von Kanälen, die durch den ganzen Körper gehen, ein System, welches das übernimmt, was durch den Verdauungsapparat verarbeitet ist, und die umgewandelten Stoffe abliefert an das Blut. Und dann haben wir das dritte Glied der Menschennatur, das Blutgefäßsystem selber mit seinen weiteren oder engeren Röhren, wie es sich durch den ganzen menschlichen Organismus zieht und das zum Mittelpunkte seines ganzen Wirkens das Herz hat. Wir wissen ja, daß vom Herzen diejenigen bluterfüllten Gefäße ausgehen, die wir die Arterien nennen, und daß diese nach allen Teilen unseres Organismus das sogenannte rote Blut hinführen. Das Blut macht einen gewissen Prozeß in den einzelnen Gliedern des menschlichen Organismus durch, wird dann wiederum zurückgeführt durch andere Gefäße, die Venen, die es aber jetzt in verändertem, verwandeltem Zustande als sogenanntes blaues Blut zu dem Herzen zurückbringen. Wir wissen auch, daß dieses verwandelte, unbrauchbar gewordene Blut von dem Herzen in die Lunge geleitet wird, daß es dort in Berührung kommt mit dem von außen aufgenommenen Sauerstoff der Luft, daß es dadurch erneuert und dann wiederum in Venen zum Herzen zurückgeleitet wird, um von neuem den Umlauf durch den ganzen menschlichen Organismus zu beginnen.

Um diese komplizierten Systeme zu betrachten, wollen wir uns, damit wir in der äußeren Betrachtungsweise gleich eine Grundlage haben für die okkulte Betrachtungsweise, zunächst an dasjenige System halten, das von vornherein jedem als das eigentliche Mittelpunktsystem des ganzen menschlichen Organismus erscheinen muß: das Blut-Herzsystem. Wir wollen dabei zunächst ins Auge fassen, wie das Blut, nachdem es als verbrauchtes Blut in der Lunge aufgefrischt ist, also aus dem sogenannten blauen Blut wieder in rotes Blut verwandelt worden ist, wieder zum Herzen zurückkehrt und dann vom Herzen als rotes Blut wiederum ausströmt in den Organismus, um hier verwendet zu werden. (Es wird an die Tafel gezeichnet.) Beachten Sie, daß alles, was ich hier zeichne, nur ganz schematisch ist. Rufen wir uns kurz ins Gedächtnis, daß das menschliche Herz ein Organ ist, das eigentlich aus vier Gliedern zunächst besteht, aus vier Kammern, die durch Innenwände so abgegrenzt sind, daß man unterscheiden kann zwei größere Räume nach unten gelegen und zwei kleinere nach oben gelegen, die beiden unteren die beiden Herzkammern, wie man sie gewöhnlich nennt, während die oberen die Vorkammern genannt werden. Ich will heute noch nicht von den Herzklappen sprechen, sondern den Gang der wichtigsten Organtätigkeiten ganz schematisch ins Auge fassen. Da zeigt sich zunächst, daß das Blut, nachdem es aus der linken Vorkammer in die linke Herzkammer geströmt ist, durch eine große Schlagader abfließt und von da aus in den ganzen Organismus geleitet wird. Nun wollen wir ins Auge fassen, daß dieses Blut zunächst in alle einzelnen Organe des Organismus sich verteilt, daß es dann im Organismus verbraucht wird, wodurch es in das sogenannte blaue Blut verwandelt wird und als solches wieder zum Herzen in die rechte Vorkammer zurückkehrt, von dort in die rechte Herzkammer fließt, um von hier aus wieder in die Lunge zu gehen, wieder erneuert zu werden und den Gang durch den Organismus von neuem zu machen.

Wenn wir uns dies vorstellen, so ist es zur Grundlage einer okkulten Betrachtungsweise wichtig zu bedenken, daß sehr früh von der Hauptschlagader eine Nebenströmung abgeht, welche ins Gehirn führt, die oberen Organe des Menschen versorgt und von dort als verbrauchtes Blut wieder zurückfließt in die rechte Vorkammer, und daß es als das Gehirn passiert habendes Blut ebenso verwandelt wird wie das Blut, das aus den übrigen Gliedern des Organismus kommt. Wir haben also einen kleineren Nebenkreislauf des Blutes, in welchen Sinnesorgane das Gehirn eingeschaltet ist, abgetrennt von dem anderen, großen Kreislauf, der den ganzen übrigen Organismus versorgt. Nun ist es außerordentlich wichtig, daß wir gerade diese Tatsache ins Auge fassen. Denn wir bekommen eine richtige Vorstellung, die uns eine Grundlage geben kann für alles, was uns möglich machen wird, in die okkulten Höhen hinaufzusteigen, nur dann, wenn wir uns die Frage stellen: Ist denn - in ähnlicher Weise, wie in den kleinen Blutkreislauf die oberen Organe eingeschaltet sind, namentlich das Gehirn - in den großen Blutkreislauf, der den übrigen Organismus versorgt, etwas ähnliches eingeschaltet? — Da kommen wir in der Tat zu dem Ergebnis, das schon die äußere oberflächliche Betrachtungsweise liefern kann, daß in den großen Blutkreislauf zunächst das Organ eingeschaltet ist, welches wir die Milz nennen, daß weiter darin eingeschaltet ist die Leber und jenes Organ, welches die von der Leber zubereitete Galle enthält. Diese Organe sind alle in den großen Blutkreislauf eingeschaltet.

Wenn wir jetzt nach der Aufgabe dieser Organe fragen, so gibt uns die äußere Wissenschaft darauf die Antwort, daß die Leber die Galle bereitet, daß die Galle über die Gallenwege abfließt in den Verdauungskanal und an der Verarbeitung der Nahrungsmittel so mitwirkt, daß diese dann aufgenommen werden können vom Lymphsystem und übergeleitet werden können in das Blut. Weniger Genaues sagt die äußere Wissenschaft über die Milz. Wenn wir diese Organe betrachten, haben wir nun zunächst den Blick darauf zu richten, daß dieselben sich sozusagen zu beschäftigen haben mit der Umwandlung der Nahrung für den menschlichen Organismus, daß aber auf der anderen Seite alle drei Organe eingeschaltet sind in den großen Blutkreislauf. In diesen sind sie nun nicht umsonst eingeschaltet. Denn insofern die Nahrungsstoffe aufgenommen werden in das Blut, um durch das Blut dem menschlichen Organismus zugeführt zu werden und demselben die Baustoffe fortwährend zu ersetzen, da beteiligen sich diese drei Organe an der notwendigen Verarbeitung der Nahrungsstoffe. Es ist nun die Frage: Können wir aus einer äußeren Beobachtung schon entnehmen, wie sich diese drei Organe an der Gesamttätigkeit des menschlichen Organismus beteiligen? — Richten wir dazu den Blick zunächst auf eine Äußerlichkeit, darauf, daß diese Organe so eingeschaltet sind in den unteren Blutkreislauf, wie das Gehirn in den oberen Kreislauf eingeschaltet ist; und fragen wir einmal - wenn wir uns zunächst wirklich an diese äußerliche Betrachtungsweise halten, die später vertieft werden soll —, ob diese Organe möglicherweise eine ähnliche, eine verwandte Aufgabe haben könnten wie das Gehirn oder überhaupt wie die höhergelegenen Teile des menschlichen Organismus. Worin könnte diese Aufgabe bestehen?

Betrachten wir einmal diese höheren Teile des menschlichen Organismus; es sind ja die Organe, welche die äußeren Sinneseindrücke aufnehmen und das Material unserer Sinneswahrnehmung verarbeiten. Daher können wir sagen: Was im menschlichen Haupt, in den oberen Partien des menschlichen Organismus geschieht, das ist Verarbeitung der Außenwelt, Verarbeitung jener Eindrücke, die von außen durch die Sinnesorgane einfließen. Die wesentlichen Ursachen für das, was in den oberen Partien des Menschen geschieht, haben wir zu sehen in den äußeren Impressionen, in den äußeren Eindrücken. Indem diese äußeren Eindrücke ihre Wirkungen hineinsenden in die oberen Organe des menschlichen Organismus, verändern sie das Blut oder tragen jedenfalls dazu bei und senden dieses Blut ebenso verändert zum Herzen zurück, wie aus dem übrigen Organismus das Blut verändert zum Herzen zurückgesandt wird. Liegt es nun nicht nahe, daran zu denken, daß das, was durch das Tor der Sinnesorgane von der Außenwelt in den oberen Teil des menschlichen Organismus hereinwirkt, in gewisser Weise demjenigen entspricht, was aus den im Innern gelegenen Organen — Milz, Leber, Galle — heraus wirkt? Der obere Teil des menschlichen Organismus schließt sich nach außen auf, um die Wirkungen der Außenwelt zu empfangen, und während das Blut nach oben strömt, um diese Eindrücke der Außenwelt aufzunehmen, strömt es nach unten, um dasjenige aufzunehmen, was von den unteren Organen kommt. Wie wir gesagt haben, werden von der Umwelt durch die Sinne Wirkungen auf unsere obere Organisation ausgeübt. Denken wir uns dies einmal zusammengezogen, zusammengepreßt in einem Zentrum, so können wir darin etwas Analoges sehen zu dem, was durch Leber, Galle und Milz bewirkt wird: Umwandlung von Stoffen, die der Außenwelt entnommen sind. Wenn wir näher darauf eingehen, werden Sie sehen, daß das keine so ganz absonderliche Betrachtungsweise ist.

Denken Sie sich die verschiedenen hereinfließenden Sinneseindrücke der Außenwelt wie zusammengezogen, gleichsam zu Organen verdichtet, ins Innere des Menschen verlegt und eingeschaltet in das Blut, so bietet sich der obere Teil des menschlichen Organismus dem Blute ebenso dar, wie sich von innen die Organe Leber, Galle, Milz dem Blute darbieten. Also wir haben die Außenwelt, die oben unsere Sinne umgibt, gleichsam in Organe zusammengedrängt und ins Innere des Menschen verlegt, so daß wir sagen können: Einmal berührt uns die Welt von außen, sie strömt durch die Sinnesorgane in unseren oberen Organismus ein und wirkt auf unser Blut, und einmal wirkt auf geheimnisvolle Weise die Welt von innen in Organen, in die sich erst zusammengezogen hat, was draußen im Makrokosmos vorgeht, und wirkt da entgegen unserem Blut, das sich ihm ebenso darbietet. Wenn wir das schematisch zeichnen wollten, könnten wir also sagen: Denken wir uns auf der einen Seite die Welt, von allen Seiten wirkend auf die Sinne, und das Blut, wie eine Tafel den Eindrücken der Außenwelt sich darbietend, so haben wir unsere obere Organisation. Denken wir uns jetzt, wir könnten diese ganze Welt zusammenziehen, in einzelne Organe zusammenziehen, einen Extrakt dieser Welt bilden, und könnten ihn in das Innere herein verlegen, so daß gewissermaßen die ganze Welt auf die andere Seite des Blutes wirkt, dann hätten wir ein schematisches Bild des Außen und des Innen des menschlichen Organismus in einer ganz sonderbaren Weise geformt. So könnten wir in einer gewissen Weise schon sagen: Es entspricht das Gehirn eigentlich unserer Innenorganisation; insoweit sie Brust- und Bauchhöhle ausfüllt, ist gleichsam die Außenwelt in unser Inneres verlegt.

Schon in dieser Organisation, die wir ja als eine untergeordnete erkennen, die hauptsächlich der Fortführung des Ernährungsprozesses dient, haben wir etwas so Geheimnisvolles wie eine Zusammenfügung der ganzen Außenwelt in eine Summe von inneren Organen, von inneren Werkzeugen. Und wenn wir nun diese Organe Leber, Galle, Milz einmal näher betrachten, können wir sagen: Zunächst ist es die Milz, die sich der Blutströmung darbietet. Die Milz ist ein sonderbares Organ, in der in blutreiche Gewebe eingebettet ist eine ganze Summe von kleinen Körnchen, die sich gegenüber der übrigen Gewebemasse weiß ausnehmen. Wenn wir das Blut im Verhältnis zur Milz betrachten, erscheint uns die Milz wie ein Sieb, durch welches das Blut hindurchgeht, um sich einem solchen Organ darzubieten, das in gewisser Weise ein zusammengeschrumpfter Teil des Makrokosmos ist. Als nächste Stufe sehen wir dann, wie sich das Blut der Leber darbietet und wie die Leber ihrerseits die Galle absondert, die in einem besonderen Organ aufbewahrt wird, dann in die Nahrungsstoffe übergeht und von dort aus mit den verwandelten Nahrungsstoffen in das Blut gelangt.

Dieses innere Sichdarbieten des Blutes an die drei Organe können wir uns nicht anders als in folgender Weise vorstellen: Das erste Organ, das sich dem Blut entgegenstellt, ist die Milz, das zweite die Leber, und das dritte, das eigentlich ein sehr kompliziertes Verhältnis schon zum gesamten Blutsystem hat, ist die Galle. Weil die Galle den Nahrungsstoffen dargeboten wird und an der Verarbeitung derselben beteiligt ist, wird sie als besonderes Organ gezählt. Aus bestimmten Gründen haben die Okkultisten aller Zeiten diesen Organen gewisse Namen gegeben. Ich bitte Sie nun recht sehr, vorläufig bei diesen Namen, die diesen Organen gegeben sind, an nichts Besonderes zu denken und davon abzusehen, daß diese Namen noch etwas anderes in der großen Welt bedeuten. Wir werden später noch sehen, warum gerade diese Namen genommen wurden. Weil die Milz sich dem Blut zuerst darbietet - so können wir rein äußerlich vergleichsweise sagen -, erschien sie den alten Okkultisten am besten mit jenem Namen bezeichnet, der dem Stern zukommt, der sich im Weltenraum zuerst im Sonnensystem darbietet; deshalb nannten sie die Milz Saturnus oder einen inneren Saturn im Menschen. In ähnlicher Weise nannten sie die Leber einen inneren Jupiter und die Galle einen inneren Mars. Wollen wir zunächst bei diesen Namen uns gar nichts anderes denken, als daß wir sie aus dem Grunde wählen, weil wir die Anschauung gewonnen haben, zunächst hypothetisch, daß die äußeren Welten, die sonst unseren Sinnen zugänglich sind, zusammengezogen sind in diesen Organen und uns gleichsam als innere Welten entgegentreten, wie uns äußerliche Welten in den Planeten entgegentreten. Wir würden aber jetzt schon sagen können: Wie die äußeren Welten unseren Sinnen erscheinen, indem sie von außen eindringen und auf das Blut wirken, so erscheinen uns die Innenwelten wirksam auf das Blut, indem sie dasselbe ebenfalls beeinflussen.

Wir werden nun allerdings einen bedeutungsvollen Unterschied finden zwischen dem, was wir gestern besprochen haben als Eigentümlichkeiten des menschlichen Gehirns, und dem, was wie eine Art inneres Weltensystem auf unser Blut wirkt. Dieser Unterschied liegt einfach darin, daß der Mensch zunächst nichts von dem weiß, was sich innerhalb seines unteren Organismus abspielt; das heißt, er weiß nichts von den Eindrücken, welche die innere Welt — gleichsam die inneren Planeten — auf ihn machen, wogegen es ja gerade charakteristisch ist, daß die äußeren Welten auf sein Bewußtsein ihre Eindrücke machen. In einer gewissen Beziehung dürfen wir also diese innere Welt als die Welt des Unbewußten bezeichnen gegenüber der bewußten Welt, welche wir im Gehirnleben kennengelernt haben.

Nun wird sich uns gerade das, was in diesem Bewußten und Unbewußten liegt, dadurch näher aufklären, daß wir etwas anderes zu Hilfe nehmen. Sie wissen alle, daß die äußere Wissenschaft davon spricht, daß das Nervensystem das Organ des Bewußtseins ist mit allem, was dazugehört. Nun müssen wir als Grundlage für unsere okkulten Betrachtungen eine gewisse Beziehung ins Auge fassen, die das Nervensystem zum Blutsystem hat, das heißt zu dem, was wir ja heute schematisch ins Auge gefaßt haben. Da sehen wir, daß unser Nervensystem überall in gewisse Beziehungen tritt zu unserem Blutsystem, daß das Blut überall an unser Nervensystem herandringt. Dabei müssen wir nun zunächst auf das Rücksicht nehmen, was die äußere Wissenschaft diesbezüglich für etwas Ausgemachtes hält. Sie ‚hält das für ausgemacht, daß im Nervensystem der gesamte Regulator liege aller Bewußtseinstätigkeit, alles dessen, was wir als bewußtes Seelenleben bezeichnen. Wir können nicht umhin — zunächst auch nur andeutungsweise, um es später zu belegen -, uns zum Bewußtsein zu bringen, daß das Nervensystem für den Okkultisten nur wie eine Art von Grundlage des Bewußtseins dasteht. Denn gerade so, wie sich in unseren Organismus eingliedert das Nervensystem und berührt wird oder wenigstens in einem gewissen Verhältnis steht zum Blutsystem, so gliedert sich in die Gesamtwesenheit des Menschen dasjenige ein, was wir nennen des Menschen astralischen Leib und des Menschen Ich. Und schon eine äußerliche Betrachtung kann uns zeigen — und ich habe ja öfter in meinen Vorträgen darüber gesprochen -, daß das Nervensystem in einer gewissen Weise eine Offenbarung des Astralleibes ist und das Blut eine Offenbarung des Ich. Wenn wir in die unbelebte Natur gehen, so sehen wir ja, wie wir den Gesteinen, Mineralien und so weiter nur einen physischen Leib zuzuschreiben haben in den Teilen, die sie uns darbieten. Wenn wir dann von den unbelebten, unorganischen Naturkörpern zu den belebten Naturkörpern aufsteigen zu den Organismen, so müssen wir uns denken, daß diese Organismen durchsetzt sind von dem sogenannten Ätherleib oder Lebensleib, der in sich die Ursachen der Lebenserscheinungen enthält. Wir werden später schon sehen, daß die Geisteswissenschaft von diesem Ather- oder Lebensleib nicht so spricht, wie die äußere Wissenschaft von einer spekulativen Lebenskraft gesprochen hat. Wenn die Geisteswissenschaft vom Ätherleibe spricht, spricht sie von etwas, was das geistige Auge wirklich sieht, also von einem Realen, das dem äußeren, physischen Leibe zugrundeliegt. Wenn wir die Pflanzen betrachten, müssen wir ihnen einen Ätherleib zuschreiben. Steigen wir hinauf von den Pflanzen zu den empfindenden Wesen, den Tieren, so ist es das Element des Empfindens, des inneren Erlebens, welches das Tier von der Pflanze unterscheidet. Wenn wir uns nun fragen, was muß sich eingliedern dem tierischen Organismus, damit er hinaufgehoben werden kann von den bloßen Lebensvorgängen zu Empfindungen, die die Pflanzen noch nicht haben, so ist die Antwort: Soll die bloße Lebenstätigkeit, die sich noch nicht verinnerlichen kann, noch nicht zur Empfindung entzünden kann, sich zur Empfindung, zum innerlichen Erleben entzünden können, so muß sich in den tierischen Organismus eingliedern der Astralleib. Und in dem Nervensystem, das die Pflanzen noch nicht haben, müssen wir den äußeren Ausdruck, das Werkzeug des Astralleibes sehen. Der Astralleib ist das geistige Urbild des Nervensystems. Wie das Urbild zu seiner Offenbarung, zu seinem Abbild, so verhält sich der Astralleib zu dem Nervensystem.

Wenn wir nun mit unserer Betrachtung beim Menschen einsetzen — und ich habe schon gestern gesagt, daß wir es im Okkultismus nicht so gut haben wie die äußere wissenschaftliche Betrachtungsweise, daß wir nicht sozusagen alles durcheinanderwerfen können -, dann müssen wir, wenn wir die menschlichen Organe betrachten, uns immer bewußt sein, daß diese Organe oder Organsysteme zu etwas gebraucht werden können, wozu die analogen Organsysteme im tierischen Organismus, wenn sie auch ähnlich ausschauen, nicht gebraucht werden können. Beim Menschen müssen wir das Blut als äußeres Werkzeug für das Ich ansehen, für alles, was wir als unser innerstes Seelenzentrum, das Ich, bezeichnen. So haben wir im Nervensystem ein äußeres Werkzeug des Astralleibes und in unserem Blut ein äußeres Werkzeug des Ich. Geradeso wie das Nervensystem im Organismus in gewisse Beziehungen tritt zum Blut, so treten diejenigen inneren Seelengebilde, die wir als unsere Vorstellungen, Wahrnehmungen, Empfindungen und so weiter erleben, in eine Beziehung zu unserem Ich. Das Nervensystem ist in der mannigfaltigsten Weise im menschlichen Organismus differenziert. Es zeigt sich uns als die inneren Nervenstränge, da, wo es sich aufschließt zum Beispiel zu Gehörnerven, Gesichtsnerven und so weiter. Das Nervensystem ist also etwas, was sich durch den Organismus so hinerstreckt, daß es in der mannigfaltigsten Weise differenziert ist, innere Mannigfaltigkeiten enthält. Wenn wir das Blut, durch den Organismus durchströmend, betrachten, so zeigt es sich uns — wenn wir absehen wollen von der Veränderung von rotem in blaues Blut im ganzen Organismus doch als einheitliches Blut. Als ein solches Einheitliches tritt es dem differenzierten Nervensystem entgegen, wie das Ich dem Seelenleben entgegentritt, das sich gliedert in Vorstellungen, Empfindungen, Willensimpulse, Gefühle und dergleichen. Je weiter Sie diesen Vergleich verfolgen werden - und das soll ja zunächst auch nur vergleichsweise gesagt sein —, desto mehr wird sich Ihnen zeigen, daß eine weitgehende Ähnlichkeit besteht in der Beziehung der beiden Urbilder Ich und Astralleib zu ihren Abbildern, ihren Werkzeugen: Blutsystem und Nervensystem. Nun können wir allerdings sagen: Blut ist überall Blut, aber indem es durch den Organismus strömt, verändert es sich. Wir können diese Veränderungen des Blutes in Parallele bringen mit den Veränderungen, die das Ich durch die verschiedenen Seelenerlebnisse erfährt. Auch unser Ich ist ein Einheitliches. So weit wir zurückdenken können im Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, können wir von uns sagen: Ich war da! In unserem fünften Jahr wie in unserem sechsten Jahr, gestern wie heute ist es dasselbe Ich. -— Aber wenn wir jetzt auf den Inhalt eingehen, auf das, was dieses Ich enthält, so werden wir finden, daß dieses Ich, wie es in mir lebt, angefüllt ist mit einer größeren oder kleineren Summe von Vorstellungen, Empfindungen, Gefühlen und so weiter, die dem Astralleibe zuzuschreiben sind und mit dem Ich in Berührung kommen. Vor einem Jahre war unser Ich mit einem anderen Inhalt erfüllt, gestern hatte es einen anderen Inhalt und heute wieder einen anderen. Das Ich kommt also mit dem gesamten Seeleninhalt in Berührung, durchströmt diesen gesamten Seeleninhalt. Geradeso wie das Blut den ganzen Organismus durchströmt und überall mit dem differenzierten Nervensystem in Berührung kommt, so kommt das Ich zusammen mit dem differenzierten Leben der Seele, mit Vorstellungen, Gefühlen, Willensimpulsen und dergleichen. So also zeigt uns schon diese nur vergleichsweise Betrachtung, daß eine gewisse Berechtigung existiert, in dem Blutsystem ein Abbild des Ich zu sehen und in dem Nervensystem ein Abbild des Astralleibes, dieser beiden höheren, übersinnlichen Glieder der menschlichen Natur, während der Ätherleib sich mehr an den physischen Leib anschließt.

Nun ist es notwendig, uns zu erinnern, daß das Blut, welches in der angedeuteten Weise durch den Organismus strömt, auf der einen Seite sich darbietet der Außenwelt, vergleichsweise wie eine Tafel den Eindrücken der Außenwelt entgegentritt, auf der anderen Seite sich dem entgegenhält, was wir die innere Welt genannt haben. Ja, so ist es auch mit unserem Ich. Wir richten unser Ich zunächst auf die Außenwelt, nehmen die äußeren Eindrücke auf. Da ergibt sich ein mannigfaltiger Inhalt in unserem Ich; es wird erfüllt von den Impressionen, die von außen kommen. Dann gibt es auch diejenigen Augenblicke, wo das Ich sozusagen in sich selber bleibt, wo es hingegeben ist seinem Schmerz, seinem Leid, an Lust und Freude, an die inneren Gefühle und so weiter, wo es sogar aus dem Gedächtnis aufsteigen läßt, was es jetzt nicht unmittelbar durch die Berührung mit der Außenwelt empfängt, sondern das, was es in sich trägt. Also auch in dieser Beziehung ist das Ich zu parallelisieren mit dem Blut, daß es sich wie eine Tafel darbietet einmal der äußeren Welt und einmal der inneren Welt; und wir könnten dieses Ich genauso schematisch darstellen, wie wir das Blut schematisch dargestellt haben (siehe Zeichnung Seite 42). Wir können die äußeren Eindrücke, die das Ich bekommt, indem es sie als Vorstellungen, als Seelengebilde faßt, in dieselbe Beziehung bringen zum Ich, wie wir die realen, durch die Sinne zu uns kommenden äußeren Vorgänge zum Blut in Beziehung gebracht haben; wir können also die Seelenereignisse, genauso wie beim körperlichen Leben, auf der einen Seite zum Blut, auf der anderen Seite zum Ich in Beziehung bringen.

Betrachten wir von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus das Zusammenwirken und das Einander-Entgegenwirken von Blut und Nerven. Wenn wir zum Beispiel unser Auge auf die Außenwelt hinwenden, so wirken die äußeren Impressionen — Farben, Lichteindrücke und so weiter — auf die Sehnerven. Solange wir die Augen auf die Außenwelt richten, so lange können wir auch davon sprechen, daß die Eindrücke der Außenwelt auf unsere Sehnerven, also das Werkzeug des Astralleibes, eine Wirkung haben. In dem Augenblick, wo ein Verhältnis eintritt zwischen Nerven und Blut, können wir davon sprechen, daß der parallele Seelenvorgang der ist, daß die mannigfaltigen Vorstellungen des Seelenlebens zu dem Ich in Beziehung treten. Wir müssen also, wenn wir das schematisch zeichnen wollen, uns das Verhältnis von Nerven und Blut so denken, wie wenn das, was durch die Nerven von außen einströmt, in Beziehung tritt zu den Blutläufen, die in die Nähe der Sehnerven kommen.

Diese Beziehung ist nun etwas außerordentlich Wichtiges, wenn man den menschlichen Organismus so betrachten will, daß die Betrachtung eine Grundlage für die okkulte Anschauung der menschlichen Natur ergeben kann. Dann müssen wir uns sagen: Beim gewöhnlichen Leben, wie es im allgemeinen verfließt, geschieht der Vorgang so, daß eine Wirkung, die durch den Nerv sich fortpflanzt, in das Blut sich einschreibt wie in eine Tafel und dadurch in das Werkzeug des Ich sich eingeschrieben hat. Nehmen wir aber einmal an, wir würden die Beziehung zwischen Blutlauf und Nerv künstlich unterbrechen, das heißt, wir würden also künstlich den Menschen in eine solche Lage bringen, daß gleichsam der Nerv in seiner Wirksamkeit von dem Blutlauf entfernt wird, so daß sie nicht mehr aufeinander wirken können. Das kann man schematisch in der Weise zeichnen, daß man die beiden Glieder weiter auseinander zeichnet, so daß eine Wechselwirkung zwischen Nerv und Blut nicht mehr stattfinden kann. Da kann die Sache so liegen, daß zunächst auf den Nerven kein Eindruck gemacht wird. So etwas kann man ja erreichen, indem man zum Beispiel den Nerv durchschneidet. Wenn es auf irgendeine Weise zustande kommt, daß ein Nerv durchschnitten ist, daß also auf den Nerv kein Eindruck gemacht wird, dann ist es ja nicht weiter wunderbar, daß der Mensch auch nichts Besonderes durch diesen Nerv erleben kann. Nehmen wir aber an, es werde — trotzdem die Beziehung zwischen Nerv und Blut unterbrochen ist — ein gewisser Eindruck gemacht. Im äußeren Experiment kann das ja dadurch herbeigeführt werden, daß man zum Beispiel durch einen elektrischen Strom den Nerv reizt. Diese äußere Beeinflussung des Nervs geht uns hier aber nichts an. Es gibt aber noch eine andere Beeinflussung des Nervs, die zu einem Zustande führt, wo er auf die Blutbahn nicht wirken kann. Dieser Zustand kann für den menschlichen Organismus herbeigeführt werden — und er wird auch herbeigeführt — durch gewisse Vorstellungen, gewisse Ideen, Empfindungen und Gefühle, die der Mensch erlebt und sich angeeignet hat und die, damit ein solches Experiment gelinge, höhere moralische oder intellektuelle Vorstellungen sein sollten. Wenn der Mensch sich solche Vorstellungen macht, zum Beispiel von Sinnbildern, und sich in scharfer innerer Konzentration der Seele übt, dann bewirkt das, daß er gleichsam den Nerv voll in Anspruch nimmt und ihn dadurch zurückzieht vom Blutlaufe. Wenn der Mensch im wachen Bewußtsein sich den normalen äußeren Eindrücken überläßt, wie sie gerade kommen, dann ist die natürliche Verbindung zwischen Nerv und Blutlauf da. Wenn der Mensch aber sich durch scharfe innere Konzentration von der Wirkung der äußeren Eindrücke abzieht, dann hat er ja das in der Seele, was erst im Bewußtsein entsteht; was Inhalt des Bewußstseins ist, nimmt den Nerv vorzugsweise in Anspruch und trennt dadurch die Nerventätigkeit ab von der Bluttätigkeit. Die Folge einer solchen inneren Konzentration, die — wenn sie stark genug ist— wirklich die Leitung zwischen Nerv und Blut unterbricht, ist, daß der Nerv in einer gewissen Weise befreit wird von dem Zusammenhang mit dem Blutsystem, ja auch befreit wird von dem, wofür das Blutsystem das äußere Werkzeug ist, das heißt also befreit wird von den gewöhnlichen Erlebnissen des Ich. Und es ist in der Tat so — und das kann vollständig experimentell belegt werden -, daß durch die Erlebnisse der geistigen Schulung, die in die höheren Welten hinaufführen soll, durch die anhaltende scharfe Konzentration das gesamte Nervensystem zeitweise dem gewöhnlichen Zusammenhang mit dem Blutsystem und dessen Aufgaben für das Ich entrückt wird. Da tritt nun eine gewisse Folge ein, nämlich die, daß das Nervensystem, das früher seine Wirkung auf die Tafel des Blutes geschrieben hat, nunmehr das, was es als Wirkung in sich enthält, in sich selbst zurücklaufen läßt, in sich zurückniimmt und diese Wirkung nicht bis zum Blut hinkommen läßt. Es ist also möglich, rein durch Vorgänge innerer Konzentration, sein Blutsystem von dem Nervensystem gleichsam abzutrennen und dadurch dasjenige, was sonst in das Ich - bildlich gesprochen — hineingeflossen wäre, zum Zurücklaufen in das Nervensystem zu bringen.

Nun ist das Eigentümliche, daß der Mensch, wenn er durch innere Seelentätigkeit wirklich so etwas bewirkt, dann eine ganz andere Art des inneren Erlebens hat und damit vor einem vollständig veränderten Bewußtseinshorizont steht. Wir können sagen: Wenn Nerven und Blut in der gewöhnlichen Weise miteinander in Wechselwirkung stehen, wie es im normalen Leben der Fall ist, dann bezieht der Mensch die Eindrücke, die von außen kommen, auf sein Ich. Wenn er aber durch innere Konzentration, durch innere Seelentätigkeit sein Nervensystem heraushebt aus der Wirkung auf sein Blutsystem, dann lebt er auch nicht in seinem bisherigen gewöhnlichen Ich; er kann dann nicht in demselben Sinne zu dem, was er jetzt als sein Selbst hat, «Ich» sagen. Der Mensch erscheint sich dann so, wie wenn er einen Teil seiner Wesenheit ganz bewußt aus sich herausgehoben hätte, abgesondert von seinem Blutsystem; es ist so, wie wenn etwas, was man sonst nicht sieht, ein Übersinnliches, in unsere Nerven hereinwirkt, das sich nicht auf unsere Bluttafel abdruckt und auf unser gewöhnliches Ich keinen Eindruck macht. Der Mensch fühlt sich hinweggehoben von dem ganzen Blutsystem, gleichsam herausgehoben aus dem Organismus. Es ist ein bewußtes Herausheben des Ich aus dem Wirkungsbereich des Astralleibes. Während nun früher die Nerventätigkeit im Blutsystem abgebildet wurde, wird sie jetzt in sich selbst zurückreflektiert; jetzt lebt der Mensch in etwas anderem, da empfindet er sich in einem anderen Ich, in einem [makrokosmischen] Ich, das früher nur geahnt werden konnte: Er fühlt das Hereinragen einer übersinnlichen Welt.

Wenn wir noch einmal die Beziehung zwischen dem Nerv oder dem gesamten Nervensystem, wie es die Eindrücke einer äußeren Welt in sich hereinnimmt, zum Blut genauer schematisch zeichnen wollen, so kann es in folgender Weise geschehen:

Würden äußere Eindrücke, äußere Erlebnisse einfließen, dann würden sie sich abdrücken im Blutsystem. Haben wir aber das Nervensystem herausgehoben aus dem Blutsystem, dann fließt alles innerhalb des Nervensystems zurück, dann ergießt sich eine Welt, von der wir früher keine Ahnung hatten, gleichsam bis an die Enden unseres Nervensystems, und das fühlen wir als Rückstoß. Während es beim gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein so ist, daß man eine Welt aufnimmt, die hineingeht bis zum Blutsystem, dem Blutsystem wie auf einer Tafel eingeschrieben wird, geht man nunmehr mit den Eindrükken nur bis dahin, wo die Nerven endigen und in sich selbst einen Widerstand finden. An diesen Nervenendungen prallt man gleichsam zurück und lebt sich hinaus in die übersinnliche Welt. Wenn wir einen Farbeneindruck haben, den wir durch das Auge empfangen, so geht er in unseren Sehnerv hinein, drückt sich ab auf der Tafel des Blutes, und wir fühlen das, was wir mit den Worten ausdrücken: Ich sehe rot. - Nehmen wir aber an, wir gehen mit unseren Eindrücken nicht bis zum Blut hin, sondern nur bis zur Endung des Nervs, prallen da zurück, so leben wir im Grunde genommen bis zu unserem Sehnerv hin. Wir prallen vor dem körperlichen Ausdruck unseres Blutes zurück, leben außerhalb unserer selbst; wir sind eigentlich in den Strahlen des Lichtes, die sonst den Eindruck «rot» in uns hervorriefen, darinnen. Wir sind also wirklich aus uns herausgekommen, und zwar dadurch, daß wir nicht so tief in unser Inneres hereindringen, wie wir es sonst tun, sondern daß wir nur bis zu den Nervenenden gehen. Das bewirkt aber ein solches Seelenleben, das den physischen Menschen wie etwas Äußerliches empfindet und sich nicht länger mit ihm identifiziert. Das normale Bewußtsein geht bis zum Blute hin. Wenn wir aber die Seele so entwickelt haben, daß wir gleichsam an den Nervenenden kehrtmachen, dann haben wir das Blut ausgeschaltet von dem, was wir den höheren Menschen nennen, zu dem wir kommen können, wenn wir von uns selber loskommen.

Durch diese Betrachtungen haben wir zunächst eine Anschauung von den Vorgängen gewonnen, die eintreten, wenn wir das Blutsystem, welches wir betrachtet haben wie eine Art Tafel, die sich auf der einen Seite den äußeren, auf der anderen Seite den inneren Eindrücken darbietet, ausgeschaltet haben von dem, was wir nennen können den höheren Menschen, zu dem wir uns entwickeln können, wenn wir von uns selber loskommen und frei werden von den Einwirkungen des gewöhnlichen Ich. Wir werden nun am besten die ganze innere Natur dieses Blutsystems studieren können, wenn wir uns nicht in allgemeinen Phrasen bewegen, sondern das am Menschen betrachten, was real ist, den übersinnlichen, unsichtbaren Menschen, zu dem wir uns selber aufschwingen können. Wenn wir diesen übersinnlichen Menschen so betrachten, wie er sich hineinbegibt bis zum Blute hin, dann werden wir zu dem Gedanken vorrücken können, daß der Mensch in der Außenwelt leben kann, daß er sich ergießen kann über die ganze Außenwelt, aufgehen kann in dieser Außenwelt und daß er gleichsam den umgekehrten Standpunkt einnehmen kann zu seinem inneren Wesen. Kurz, wir werden die Funktionen des Blutes und der Organe, die in den Blutkreislauf eingeschaltet sind, dadurch kennenlernen, daß wir die Frage beantworten: Wie muß nun diese höhere Welt, zu der sich der Mensch aufschwingen kann, die er genau kennenlernen kann, sich auf die Tafel des Blutes abmalen? — Da wird sich uns das ganze differenzierte Blutleben als der Mittelpunkt des Menschen ergeben, wenn wir unmittelbar die Beziehungen dieses wunderbaren Systems zu einer höheren Welt betrachten. Denn das wird ja unsere Aufgabe sein, daß wir den Menschen ansehen können als eine Offenbarung des Übersinnlichen, daß wir den äußeren Menschen ansehen können als ein Abbild desjenigen Menschen, der in der geistigen Welt wurzelt. Dadurch werden wir den menschlichen Organismus erkennen können als ein getreues Abbild des Geistes.

Second Lecture

Within these considerations, we will repeatedly encounter the difficulty of examining the external human organism more closely in order to recognize, so to speak, what is transitory and fragile. But we will also see that it is precisely this path that will lead us to an understanding of what is lasting, imperishable, and eternal in human nature. However, if our considerations are to have this goal, it is necessary that we strictly adhere to what was already noted yesterday in the introduction: the point of view that the outer physical organism should be regarded with all reverence as a revelation from spiritual worlds.