From Jesus to Christ

GA 131

9 October 1911, Karlsruhe

Lecture V

If you recall that in the course of our lectures we have come to look upon the Christ-Impulse as the most profound event in human evolution, you will doubtless agree that some exertion of our powers of mind and spirit is needed to understand its full meaning and range of influence. Certainly in the widest circles we find the bad habit of saying that the highest things in the world must be comprehensible in the simplest terms. If what someone is constrained to say about the sources of existence appears complicated, people turn away from it because ‘the truth must be simple’. In the last resort it certainly is simple. But if at a certain stage we wish to learn to know the highest things, it is not hard to see that we must first clear the way to understanding them. And in order to enter into the full greatness, the full significance, of the Christ-Impulse, from a particular point of view, we must bring together many different matters.

We need only turn to the Pauline Epistles and we shall soon see that Paul, who sought especially to bring within range of human minds the super-sensible nature of the Christ-Being, has drawn into the concept, the idea, of the Christ, the whole of human evolution, so to speak. If we let the Pauline Epistles work upon us, we have finally something which, through its extraordinary simplicity and through the deeply penetrating quality of the words and sentences, makes a most significant impression. But this is so only because Paul, through his own initiation, had worked his way up to that simplicity which is not the starting-point of what is true, but the consequence, the goal. If we wish to penetrate into what Paul was able finally to express in wonderful, monumental, simple words concerning the Christ-Being, we must come nearer to an understanding of human nature, for whose further development on Earth the Christ-Impulse came. Let us therefore consider what we already know concerning human nature, as shown through occult sight.

We divide the life of Man into two parts: the period between birth and death, and the period which runs its course between death and a new birth. Let us first of all look at man in his physical body. We know that occult sight sees him as a four-fold being, but as a four-fold being in process of development. Occult sight sees the physical body, etheric body, astral body and the Ego. We know that in order to understand human evolution we must learn the occult truth that this Ego, of which we become aware in our feelings and perceptions when we simply look away from the external world and try to live within ourselves, goes on from incarnation to incarnation. But we also know that this Ego is, as it were, ensheathed—although ‘ensheathed’ is not a good expression, we can use it for the present—by three other members of human nature, the astral body, the etheric body and the physical body. Of the astral body we know that in a certain respect it is the companion of the Ego through the various incarnations. For though during the Kamaloka time much of the astral body must be shed, it remains as a kind of force-body, which holds together the moral, intellectual and aesthetic progress we have stored up during an incarnation. Whatever constitutes true progress is held together by the power of the astral body, is carried from one incarnation to another, and is linked, as it were, with the Ego, which passes as the fundamentally eternal in us from incarnation to incarnation. Further, we know that from the etheric body, too, very much is cast off immediately after death, but an extract of this etheric body remains with us, an extract we take with us from one incarnation to another. In the first days directly after death we have before us a kind of backward review, like a great tableau, of our life up to that time, and we take with us a concentrated etheric extract. The rest of the etheric body is given over into the general etheric world in one form or another, according to the development of the person concerned.

When, however, we look at the fourth member of the human being, the physical body, it seems at first as if the physical body simply disappears into the physical world. One might say that this can be externally demonstrated, for to external sight the physical body is brought in one way or another to dissolution. The question, however, which everyone who occupies himself with Spiritual Science must put to himself is the following. Is not all that external physical cognition can tell us about the fate of our physical body perhaps only Maya? The answer does not lie very far away for anyone who has begun to understand Spiritual Science. When a man can say to himself, ‘All that is offered by sense-appearance is Maya, external illusion’, how can he think it really true that the physical body, delivered over to the grave or to the fire, disappears without trace, however crudely the appearance may obtrude on his senses? Perhaps, behind the external Maya, there lies something much deeper. Let us go further into this.

You will realise that in order to understand the evolution of the Earth, we must know the earlier embodiments of our planet; we must study the Saturn, Sun, and Moon embodiments of the Earth. We know that the Earth has gone through its ‘incarnations’ just as every human being has done. Our physical body was prepared in the course of human evolution from the Saturn period of the Earth. With regard to the ancient Saturn time we cannot speak at all of etheric body, astral body, and Ego in the sense of the present day. But the germ for the physical body was already sown, was embodied, during the Saturn evolution. During the Sun period of the Earth this germ was transformed, and then in this germ, in its altered form, the etheric was embodied. During the Moon period of the Earth the physical body was again transformed, and in it, and at the same time in the etheric body, which also came forth in an altered form, the astral body was incorporated. During the Earth period the Ego was incorporated. And is it conceivable that the part of us which was embodied during the Saturn period, our physical body, simply decomposes or is burned up and disappears into the elements, after the most significant endeavours had been made by divine-spiritual Beings through millions and millions of years, during the Saturn, Sun and Moon periods, in order to produce this physical body? If this were true, we should have before us the very remarkable fact that through three planetary stages, Saturn, Sun, Moon, a whole host of divine Beings worked to produce a cosmic element, such as our physical body is, and that during the Earth period this cosmic element is destined to vanish every time a person dies. It would be a remarkable drama if Maya—and external observation knows nothing else—were right. So now we ask: Can Maya be right?

At first it certainly seems as though occult knowledge declares Maya to be correct, for, strangely enough, occult knowledge seems in this case to harmonise with Maya. When we study the description given by spiritual knowledge of the development of man after death, we find that scarcely any notice is taken of the physical body. We are told that the physical body is thrown off, is given over to the elements of the Earth. We are told about the etheric body, the astral body, the Ego. The physical body is not further touched upon, and it seems as though the silence of spiritual knowledge were giving tacit assent to Maya-knowledge. So it seems, and in a certain way we are justified by Spiritual Science in speaking thus, for everything further must be left to a deeper grounding in Christology. For concerning what goes beyond Maya with regard to the physical body we cannot speak at all correctly unless the Christ-Impulse and everything connected with it has first been sufficiently explained.

If we observe how this physical body was experienced at some definite moment in the past, we shall reach a quite remarkable result. Let us enquire into three kinds of folk-consciousness, three different forms of human consciousness concerning all that is connected with our physical body, during decisive periods in human evolution. We will enquire first of all among the Greeks.

We know that the Greeks were that remarkable people who rose to their highest development in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch of civilisation. We know that this epoch began about the eighth century before our era, and ended in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries after the Event of Palestine. We can easily confirm what is said about this period from external information, traditions, and documents. The first dimly clear accounts concerning Greece hardly go back farther than the sixth or seventh century before our era, though legendary accounts come down from still earlier times. We know that the greatness of the historical period of Greece has its source in the preceding period, the third post-Atlantean epoch. The inspired utterances of Homer reach back into the period preceding the fourth post-Atlantean epoch; and Aeschylus, who lived so early that a number of his works have been lost, points back to the drama of the Mysteries, of which he offers us but an echo. The third post-Atlantean epoch extends into the Greek age, but in that age the fourth epoch comes to full expression. The wonderful Greek culture is the purest expression of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch.

Now there falls upon our ear a remarkable saying from this land of Greece, a saying which permits us to see deeply into the soul of the man who felt himself truly a Greek, the saying of the hero (Achilles, in the Odyssey): ‘Better a beggar in the upper world, than a king in the land of shades.’ Here is a saying which betrays the deep susceptibility of the Greek soul. One might say that everything preserved to us of Greek classical beauty and classical greatness, of the gradual formation of the human ideal in the external world—all this resounds to us from that saying.

Let us recall the wonderful training of the human body in Greek gymnastics and in the great Games, which are only caricatured in these days by persons who understand nothing of what Greece really was. Every period has its own ideal, and we must keep this in mind if we want to understand how this development of the external physical body, as it stands there in its own form on the physical plane, was a peculiar privilege of the Greek spirit. So, too, was the creation of human ideals in plastic art, the enhancement of the human form in sculpture. And if we then look at the character of the Greek consciousness, as it held sway in a Pericles, for example, when a man had a feeling for the universally human and yet could stand firmly on his own feet and feel like a lord and king in the domain of his city—when we let all this work upon us, then we must say that the real love of the Greek was for the human form as it stood there before him on the physical plane, and that aesthetics, too, were turned to account in the development of this form. Where this human form was so well loved and understood, one could give oneself up to the thought: ‘When that which gives to man this beautiful form on the physical plane is taken away from human nature, one cannot value the remainder as highly as the part destroyed by death.’ This supreme love for the external form led unavoidably to a pessimistic view of what remains of man when he has passed through the gate of death. And we can fully understand that the Greek soul, having looked with so great a love upon the outer form, felt sad when compelled to think: ‘This form is taken away from the human individuality. The human individuality lives on without this form!’ If for the moment one looks at it solely from the point of view of feeling, then we must say: We have in Greece that branch of the human race which most loved and valued the human body, and underwent the deepest sorrow when the body perished in death. Now let us consider another consciousness which developed about the same time, the Buddha consciousness, which had passed over from Buddha to his followers. There we have almost the opposite of the Greek attitude. We need only remember one thing: the kernel of the four great truths of Buddha is that human individuality is drawn by longing, by desire, into the existence where it is enshrouded by an external form. Into what kind of existence? Into an existence described in the Buddha-teaching as ‘Birth is sorrow, sickness is sorrow, old age is sorrow, death is sorrow!’ The underlying thought in this kernel of Buddhism is that by being enshrouded in an external bodily sheath, our individuality, which at birth comes down from divine-spiritual heights and returns to divine-spiritual heights at death, is exposed to the pain of existence, to the sorrow of existence. Only one way of salvation for men is expressed in the four great holy truths of Buddha: to become free from external existence, to throw off the external sheath. This means transforming the individuality so that it comes as soon as possible into a condition which will permit this throwing off. We note that the active feeling here is the reverse of the feeling dominant among the Greeks. Just as strongly as the Greek loved and valued the external bodily sheath, and felt the sadness of casting it aside, just as little did the adherent of Buddhism value it, regarding it as something to be cast aside as quickly as possible. And linked with this attitude was the struggle to overcome the craving for existence, an existence enshrouded by a bodily sheath.

Let us go a little more deeply into these Buddhist thoughts. A kind of theoretical view meets us in Buddhism concerning the successive incarnations of man. It is not so much a question of what the individual thinks about the theory, as of what has penetrated into the consciousness of the adherents of Buddhism. I have often described this. I have said that we have perhaps no better opportunity of feeling what an adherent of Buddhism must have felt in regard to the continual incarnations of man, than by immersing ourselves in the traditional conversation between King Milinda and a Buddhist sage. ‘Thou hast come in thy carriage: then reflect, O great King,’ said the sage Nagasena, ‘that all thou hast in the carriage is nothing but the wheels, the shaft, the body of the carriage and the seat, and beyond these nothing else exists except a word which covers wheels, shaft, body of carriage, seat, and so on. Thus thou canst not speak of a special individuality of the carriage, but thou must clearly understand that “carriage” is an empty word if thou thinkest of anything else than its parts, its members.’ And another simile was chosen by Nagasena for King Milinda. ‘Consider the almond-fruit which grows on the tree, and reflect that out of another fruit a seed was taken and laid in the earth and has decayed; out of that seed the tree has grown, and the almond-fruit upon it. Canst thou say that the fruit on the tree has anything else in common other than name and external form with the fruit from which the seed was taken and laid in the earth, where it decayed?’ A man, Nagasena meant to say, has just as much in common with the man of his preceding incarnation as the almond-fruit on the tree has with the almond-fruit which, as seed, was laid in the earth. Anyone who believes that the form which stands before us as man, and is wafted away by death, is anything else than name and form, believes something as false as he who thinks that in the carriage—in the name ‘carriage’—something else is contained than the parts of the carriage—the wheels, shaft, and so on. From the preceding incarnation nothing of what man calls his Ego passes over into the new incarnation.

That is important! And we must repeatedly emphasise that it is not to the point how this or that person chooses to interpret this or that saying of the Buddha, but how Buddhism worked in the consciousness of the people, what it gave to their souls. And what it gave to their souls is indeed expressed with intense clearness and significance in this parable of King Milinda and the Buddhist sage. Of what we call the ‘Ego’, and of which we say that it is first felt and perceived by man when he reflects upon his inner being, the Buddhist says that fundamentally it is something that flows into him, and belongs to Maya as much as everything else that does not go from incarnation to incarnation.

I have elsewhere mentioned that if a Christian sage were to be compared with the Buddhist one, he would have spoken differently to King Milinda. The Buddhist said to the King: ‘Consider the carriage, wheels, shaft, and so on; they are parts of the carriage, and beyond these parts carriage is only a name and form. With the word carriage thou hast named nothing real in the carriage. If thou wilt speak of what is real, thou must name the parts.’ In the same case the Christian sage would have said: ‘O wise King Milinda, thou hast come in thy carriage; look at it! In it thou canst see only the wheels, the shaft, the body of the carriage and so on, but I ask thee now: Canst thou travel hither with the wheels only? Or with the shaft only, or with the seat only? Thou canst not travel hither on any of the separate parts. So far as they are parts they make the carriage, but on the parts thou canst not come hither. In order that the assembled parts can make the carriage, something else is necessary than their being merely parts. There must first be the quite definite thought of the carriage, for it is this that brings together wheels, shaft, and so on. And the thought of the carriage is something very necessary: thou canst indeed not see the thought, but thou must recognise it!’

The Christian sage would then turn to man and say: ‘Of the individual person thou canst see only the external body, the external acts, and the external soul-experiences; thou seest in man just as little of his Ego as in the name carriage thou seest its separate parts. Something quite different is established within the parts, namely that which enables thee to travel hither. So also in man: within all his parts something quite different is established, namely that which constitutes the Ego. The Ego is something real which as a super-sensible entity goes from one incarnation to another.’

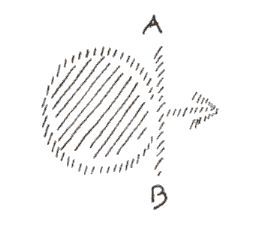

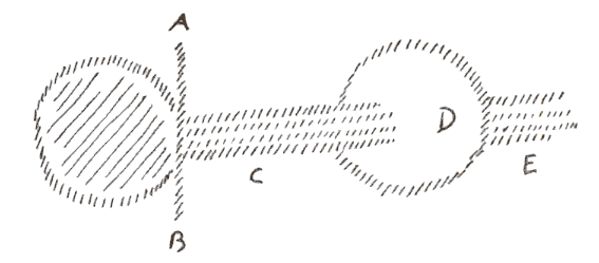

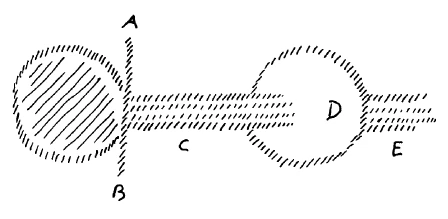

How can we make a diagram of the Buddhist teaching of reincarnation, so that it will represent the corresponding Buddhist theory? With the circle we indicate a man between birth and death. The man dies. The time when he dies is marked by the point where the circle touches the line A–B. Now what remains of all that has been spellbound within his existence between birth and death? A summation of causes: the results of acts, of everything a man has

done, good or bad, beautiful or ugly, clever or stupid. All that remains over in this way works on as a set of causes, and so forms the causal nucleus (C) for the next incarnation. Round this causal nucleus new body-sheaths (D) are woven for the next incarnation. These body-sheaths go through new experiences, as did the body-sheaths around the earlier causal nucleus. From these experiences there remains again a causal nucleus (E). It includes experiences that have come into it from earlier incarnations, together with experiences from its last life. Hence it serves as the causal nucleus for the next incarnation, and so on. This means that what goes through the incarnations consists of nothing but causes and effects. There is no continuing Ego to connect the incarnations; nothing but causes and effects working over from one incarnation into the next. So when in this incarnation I call myself an ‘Ego’, this is not because the same Ego was there in the preceding incarnation. What I call my Ego is only a Maya of the present incarnation.

Anyone who really knows Buddhism must picture it in this way, and he must clearly understand that what we call the Ego has no place in Buddhism. Now let us go on to what we know through anthroposophical cognition.

How has man ever been able to develop his Ego? Through the Earth-evolution. Only in the course of the Earth-evolution has he reached the stage of developing his Ego. It was added to his physical body, etheric body and astral body on the Earth. Now, if we remember all we had to say concerning the evolutionary phases of man during the Saturn, Sun and Moon periods, we know that during the Moon period the human physical body had not yet acquired a quite definite form; it received this first on Earth. Hence we speak of the Earth-existence as the epoch in which the Spirits of Form first took part, and metamorphosed the physical body of man so that it has its present form. This forming of the human physical body was necessary if the Ego were to find a place in man. The physical Earth-body, set down on the physical Earth, provided the foundation for the dawn of the Ego as we know it. If we keep this in mind, what follows will no longer seem incomprehensible.

With regard to the valuation of the Ego among the Greeks, we saw that for them it was expressed externally in the human form. Let us now recall that Buddhism, according to its knowledge, sets out to overcome and cast off as quickly as possible the external form of the human physical body. Can we then wonder that in Buddhism we find no value attached to anything connected with this bodily form? It is the essence of Buddhism to value the external form of the physical body as little as it values the external form which the Ego needs in order to come into being: indeed, all this is completely set aside. Buddhism lost the form of the Ego through the way in which it undervalued the physical body.

Thus we see how these two spiritual currents are polarically opposed: the Greek current, which set the highest value on the external form of the physical body as the external form of the Ego, and Buddhism, which requires that the external form of the physical body, with all craving after existence, shall be overcome as soon as possible, so that in its theory it has completely lost the Ego.

Between these two opposite world-philosophies stands ancient Hebraism. Ancient Hebraism is far from thinking so poorly of the Ego as Buddhism does. In Buddhism, it is heresy to recognise a continuous Ego, going on from one incarnation to the next. But ancient Hebraism held very strongly to this so called heresy, and it would never have entered the mind of an adherent of that religion to suppose that his personal divine spark, with which he connected his concept of the Ego, is lost when he goes through the gate of death. If we want to make clear how the ancient Hebrew regarded the matter, we must say that he felt himself connected in his inner being with the Godhead, intimately connected; he knew that through the finest threads of his soul-life, as it were, he was dependent on the being of this Godhead.

With regard to the concept of the Ego, the ancient Hebrew was quite different from the Buddhist, but in another respect he was also very different from the Greek. When we survey those ancient times as a whole, we find that the estimation of human personality, and hence that valuation of the external human form which was peculiar to the Greek, is not present in ancient Hebraism. For the Greek it would have been absolute nonsense to say: ‘Thou shalt not make to thyself any image of thy God.’ He would not have understood if someone had said to him: ‘Thou shalt not make to thyself any image of thy Zeus, or thy Apollo.’ For he felt that the highest thing was the external form, and that the highest tribute a man could offer to the Gods was to clothe them with this human form which he himself valued so much. Nothing would have seemed more absurd to him than the commandment: ‘Thou shalt make to thyself no image of God.’ As artist, the Greek gave his human form to his gods. He thought of himself as made in the likeness of the Divine, and he carried out his contests, his wrestling, his gymnastics and so on, in order to become a real copy of the God.

But the ancient Hebrew had the commandment, ‘Thou shalt make to thyself no image of God!’ This was because he did not value the external form as the Greeks had done; he regarded it as unworthy in relation to the Divine. The ancient Hebrew was as far removed on the one side from the disciple of Buddhism, who would have much preferred to cast off the human form entirely on passing through death, as he was on the other side from the Greek. He was mindful of the fact that it was this form that gave expression to the commands, the laws, of the Divine Being, and he clearly understood that a ‘righteous man’ handed down through the following generations what he, as a righteous man, had gathered together. Not the extinguishing of the form, but the handing on of the form through the generations was what concerned the ancient Hebrew. His point of view stood midway between that of the Buddhist, who had lost the value of the Ego, and that of the Greek, who saw in the form of the body the very highest, and felt it as sorrowful when the bodily form had to disappear with death.

So these three views stand over against one another. And for a closer understanding of ancient Hebraism we must make it clear that what the Hebrew valued as his Ego was in a certain sense also the Divine Ego. The God lived on in humanity, lived within man. In his union with the God, the Hebrew felt at the same time his own Ego, and felt it to be coincident with the Divine Ego. The Divine Ego sustained him; the Divine Ego was active within him. The Greek said: ‘I value my Ego so greatly that I look with horror on what will happen to it after death.’ The Buddhist said: ‘That which is the cause of the external form of man must fall away from man as soon as possible.’ The Hebrew said: ‘I am united with God; that is my fate, and as long as I am united with Him I bear my fate. I know nothing else than the identification of my Ego with the Divine Ego.’

This old Judaic mode of thought, standing midway between Greek thought and Buddhism, does not involve, as Greek thought does from the outset, a predisposition to tragedy in face of the phenomenon of death, but tragic feeling is indirectly present in it. It is truly Greek for the hero to say: ‘Better a beggar in the upper world’—i.e. with the human bodily form—‘than a king in the realm of shades’, but a Hebrew could not have said it without something more. For the Hebrew knows that when in death his bodily form falls away, he remains united with God. He cannot fall into a tragic mood simply through the fact of death. Still, the predisposition to tragedy is present indirectly in ancient Hebraism, and is expressed in the most wonderfully dramatic story ever written in ancient times, the story of Job.

We see there how the Ego of Job feels bound up with his God, how it comes into conflict with his God, but differently from the way in which the Greek Ego comes into conflict. We are shown how misfortune after misfortune falls upon Job, although he is conscious that he is a righteous man and has done all he can to maintain the connection of his Ego with the Divine Ego. And while it seems that his existence is blessed and ought to be blessed, a tragic fate breaks over him.

Job is not aware of any sin; he is conscious that he has acted as a righteous man must act towards his God. Word is brought to him that all his possessions have been destroyed, all his family slain. Then his external body, this divine form, is stricken with grievous disease. There he stands, the man who can consciously say to himself: “Through the inward connection I feel with my God, I have striven to be righteous before my God. My fate, decreed to me by this God, has placed me in the world. It is the acts of this God which have fallen so heavily upon me.” And his wife stands there beside him, and calls upon him in strange words to deny his God. These words are handed down correctly. They are one of the sayings which correspond exactly with the Akashic record: ‘Renounce thy God, since thou hast to suffer so much, since He has brought these sufferings upon thee, and die!’ What endless depth lies in these words: Lose the consciousness of the connection with thy God; then thou wilt fall out of the Divine connection, like a leaf from the tree, and thy God can no longer punish thee! But loss of the connection with God is at the same time death! For as long as the Ego feels itself connected with God, death cannot touch it. The Ego must first tear itself away from connection with God; then only can death touch it.

According to outward appearance everything is against righteous Job; his wife sees his suffering and advises him to renounce God and die; his friends come and say: ‘You must have done this or that, for God never punishes a righteous man.’ But he is aware, as far as his personal consciousness is concerned, that he has done nothing unrighteous. Through the events he encounters in the external world he stands before an immense tragedy: the tragedy of not being able to understand human existence, of feeling himself bound up with God and not understanding how what he is experiencing can have its source in God.

Let us think of all this lying with its full weight upon a human soul. Let us think of this soul breaking forth into the words which have come down to us from the traditional story of Job: ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth! I know that one day I shall again be clothed with my bones, with my skin, and that I shall look upon God with whom I am united.’ This consciousness of the indestructibility of the human individuality breaks forth from the soul of Job in spite of all the pain and suffering. So powerful is the consciousness of the Ego as the inner content of the ancient Hebrew belief! But here we meet with something in the highest degree remarkable. ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth,’ says Job, ‘I know that one day I shall again be covered with my skin, and that with mine eyes I shall behold the glory of my God.’ Job brings into connection with the Redeemer-thought the external body, skin and bones, eyes which see physically. Strange! Suddenly, in this consciousness that stands midway between Greek thought and Buddhism—this ancient Hebrew consciousness—we meet a consciousness of the significance of the physical bodily form in connection with the Redeemer-thought, which then becomes the foundation, the basis, for the Christ-thought. And when we take the answer of Job's wife, still more light falls on everything Job says. ‘Renounce thy God and die.’ This signifies that he who does not renounce his God does not die. That is implied in these words. But then, what does ‘die’ mean? To die means to throw off the physical body. External Maya seems to say that the physical body passes over into the elements of the earth, and, so to speak, disappears. Thus in the answer of Job's wife there lies the following: ‘Do what is necessary that thy physical body may disappear!’ It could not mean anything else, or the words of Job that follow would have no sense. For man can understand anything only if he can understand the means whereby God has placed us in the world; if, that is, he can understand the significance of the physical body. And Job himself says, for this too lies in his words: ‘O, I know full well that I need not do anything that would bring about the complete disappearance of my physical body, for that would be only an external appearance. There is a possibility that my body may be saved, because my Redeemer liveth. This I cannot express otherwise than in the words: My skin, my bones, will one day be recreated. With my eyes I shall behold the Glory of my God. I can lawfully keep my physical body, but for this I must have the consciousness that my Redeemer liveth.’

So in this story of Job there comes before us for the first time a connection between the Form of the physical body, which the Buddhist would strip off, which sadly the Greek sees pass away, and the Ego-consciousness. We meet for the first time with something like a prospect of deliverance for that which the host of Gods from ancient Saturn, Sun, and Moon, down to the Earth itself, have brought forth as the Form of the physical body. And if the Form is to be preserved, if we are to say of it that what has been given us of bones, skin and sense-organs is to have an outcome, then we must add: ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth.’

This is strange, someone might now say. Does it really follow from the story of Job that Christ awakens the dead and rescues the bodily Form which the Greeks believed would disappear? And is there perhaps anything in the story to indicate that for the general evolution of humanity it is not right, in the full sense of the word, that the external bodily Form should disappear completely? May it not be interwoven with the whole human evolutionary process? Has this connection a part to play in the future? Does it depend upon the Christ-Being?

These questions are set before us. And they mean that we shall have to widen in a certain connection what we have so far learnt from Spiritual Science. We know that when we pass through the gate of death we retain at least the etheric body, but we strip off the physical body entirely; we see it delivered up to the elements. But its Form, which has been worked upon through millions and millions of years—is that lost in nothingness, or is it in some way retained?

We will consider this question in the light of the explanations you have heard today, and tomorrow we will approach it by asking: How is the impulse given to human evolution by the Christ related to the significance of the external physical body—that body which throughout Earth evolution is consigned to the grave, the fire or the air, although the preservation of its Form is necessary for the future of mankind?

Fünfter Vortrag

Wenn Sie bedenken, daß aus unseren Vorträgen hervorgegangen ist, daß der Christus-Impuls als der tiefgehendste in den Entwickelungsvorgängen der Menschheit angesehen werden muß, so werden Sie es ohne Zweifel auch selbstverständlich finden, daß einige Anstrengung unserer Geisteskräfte notwendig ist, um die volle Bedeutung und den ganzen Umfang dieses Christus-Impulses zu verstehen. Es ist ja gewiß in den weitesten Kreisen die Unart vorhanden, daß man sagt, was das Höchste in der Welt sei, müsse in der allereinfachsten Weise zu begreifen sein; und wenn jemand über die Quellen des Daseins kompliziert zu sprechen gezwungen wäre, müsse man dies schon aus dem Grunde ablehnen, weil der Satz gelten müsse: die Wahrheit muß einfach sein. Zuletzt ist sie ja auch gewiß einfach. Aber wenn wir das Höchste kennenlernen wollen auf einer gewissen Stufe, so ist es unschwer einzusehen, daß wir erst einen Weg machen müssen, um das Höchste zu begreifen. Und so werden wir wieder mancherlei zusammentragen müssen, um uns von einem bestimmten Gesichtspunkte aus hineinzufinden in die ganze Größe und die ganze Bedeutung des Christus-Impulses.

Wir brauchen nur die Briefe des Paulus aufzuschlagen und wir werden bald finden, daß Paulus — von dem wir ja wissen, daß er versuchte, gerade das Übersinnliche der Christus-Wesenheit der Menschenbildung einzuverleiben — daß Paulus zum Begriffe, zur Idee des Christus sozusagen die ganze Menschheitsentwickelung herangezogen hat. Allerdings ist es ja so, wenn wir die Briefe des Paulus auf uns wirken lassen, daß wir zuletzt etwas vor uns haben, was durch seine ungeheuere Einfachheit und durch das tief Eindringliche der Worte und Sätze einen allerbedeutsamsten Eindruck macht. Aber nur aus dem Grunde ist das der Fall, weil Paulus selbst durch seine eigene Initiation sich hinaufgearbeitet hat zu jener Einfachheit, die nicht der Ausgangspunkt des Wahren, sondern die Konsequenz, das Ziel des Wahren sein kann. Wenn wir nun eindringen wollen in das, was zuletzt bei Paulus von der Christus-Wesenheit mit wunderbar monumental einfachen Worten zum Ausdruck kommt, so werden wir schon in unserer geisteswissenschaftlichen Art uns nähern müssen einem Verständnis der menschlichen Natur, zu deren Fortentwickelung innerhalb der Erde der Christus-Impuls ja gekommen ist.

Betrachten wir deshalb, was wir schon wissen über die menschliche Natur, wie sie uns für den okkulten Blick entgegentritt! Da teilen wir ja das menschliche Leben in jene zwei Glieder, die wir betrachten in bezug auf die zeitlichen Abläufe: die Zeit zwischen der Geburt oder der Empfängnis und dem Tod, und jene Zeit, welche abläuft zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Wenn wir zunächst den Menschen vor uns hinstellen, wie er im physischen Leben vor uns steht, so wissen wir, daß ihn der okkulte Blick als eine Vierheit sieht, aber als eine Vierheit, die in Entwickelung begriffen ist, als den physischen Leib, den Ätherleib, den astralischen Leib und das Ich. Und wir wissen, daß wir uns zum Verständnis der menschlichen Entwickelung bekanntmachen müssen mit der okkulten Wahrheit, daß dieses Ich — das wir gewahr werden in den Gefühlen und Empfindungen, wenn wir einfach von der Außenwelt absehen und in uns selber zu leben versuchen — daß dieses Ich für den okkulten Blick von Inkarnation zu Inkarnation geht. Wir wissen aber auch, daß dieses Ich gleichsam umhüllt ist — obwohl «umhüllt» kein guter Ausdruck ist, aber wir können ihn zunächst gebrauchen — von den drei andern Gliedern der menschlichen Natur, dem Astralleib, Ätherleib und physischen Leib. Von dem Astralleib wissen wir, daß er in einer gewissen Beziehung ein Begleiter des Ich durch die verschiedenen Inkarnationen hindurch ist. Wenn auch während der Kamaloka-Zeit vieles von dem Astralleib ausgeschieden werden muß, so bleibt uns doch dieser Astralleib durch die Inkarnationen hindurch als eine Art von Kraftleib, der zusammenhält, was wir in uns an moralischem, intellektuellem und ästhetischem Fortschritt innerhalb einer Inkarnation aufgespeichert haben. Was wirklicher Fortschritt ist, das wird zusammengehalten durch die Kraft des Astralleibes, von einer Inkarnation in die andere hineingetragen und gleichsam zusammengefügt mit dem Ich, das als das Grund-Ewige in uns von Inkarnation zu Inkarnation geht. Und weiter wissen wir, daß vom Ätherleib zwar sehr viel abgestreift wird unmittelbar nach dem Tode, daß aber doch ein Extrakt dieses Äther- oder ätherischen Leibes uns bleibt, den wir mitnehmen von einer Inkarnation in die andere hinein. Es ist das ja so, daß wir in den ersten Tagen unmittelbar nach dem Tode eine Art Rückschau haben, wie ein großes Tableau, auf unser bisheriges Leben, und daß wir die Zusammenfassung dieser Rückschau — den Extrakt — als ätherisches Resultat mit uns nehmen. Das Übrige des Ätherleibes wird der allgemeinen Ätherwelt übergeben in der einen oder andern Form, je nach der Entwickelung des betreffenden Menschen. Wenn wir nach dem vierten Gliede der menschlichen Wesenheit, nach dem physischen Leibe unser Auge richten, so sieht es zunächst so aus, als ob dieser physische Leib einfach in der physischen Welt verschwände. Das kann ja geradezu auch, man möchte sagen, äußerlich in der physischen Welt nachgewiesen werden; denn dieser physische Leib wird in der einen oder andern Weise seiner Auflösung, für den äußeren Anblick, zugeführt. Die Frage ist nur die — und ein jeder, der sich mit Geisteswissenschaft beschäftigt, sollte sie sich stellen: Ist vielleicht alles, was uns die äußere physische Erkenntnis auch über die Schicksale unseres physischen Leibes sagen kann, Maja? Und die Antwort liegt eigentlich nicht so fern für den, der angefangen hat die Geisteswissenschaft zu verstehen. Wenn man angefangen hat, die Geisteswissenschaft zu verstehen, so sagt man sich: Alles, was der Sinnenschein bietet, ist Maja, ist äußere Illusion. Wie kann man da noch erwarten, daß es wirklich wahr ist, wenn es sich auch noch so grob aufdrängt, daß der physische Leib, wenn er dem Grabe oder dem Feuer übergeben wird, spurlos verschwindet? Vielleicht verbirgt sich gerade hinter der äußeren Maja, die sich für den Sinnenschein aufdrängt, etwas viel Tieferes!

Aber wir wollen noch etwas weiter gehen: Bedenken Sie, daß wir, um die Erdentwickelung zu verstehen, die früheren Verkörperungen unseres Planeten kennen müssen; daß wir die Saturn-, die Sonnen- und die Mondverkörperung der Erde studieren müssen. Wir müssen sagen: Wie jeder einzelne Mensch, so hat auch die Erde ihre Verkörperungen durchgemacht, und das, was unser physischer Leib ist, das ist vorbereitet worden in der menschlichen Evolution seit der Saturnzeit der Erde. Während von unserem Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich in dem heutigen Sinne zur alten Saturnzeit noch gar nicht gesprochen werden kann, wird der Keim zum physischen Leibe schon während der Saturnzeit gelegt, wird gleichsam der Evolution einverleibt. Während der Sonnenzeit der Erde wird dieser Keim umgestaltet; ihm wird dann in der umgestalteten Form der Ätherleib einverleibt. Während der Mondenzeit der Erde wird wieder der physische Leib umgestaltet und ihm einverleibt — neben dem Ätherleib, der auch in umgeänderter Form wieder herauskommt — der Astralleib. Und während der Erdenzeit wird ihm das Ich einverleibt. Und nun müßten wir also, wenn der Sinnenschein richtig wäre, sagen, daß das, was uns während der Saturnzeit einverleibt worden ist, unser physischer Leib, einfach verwest oder verbrennt und in den äußeren Elementen aufgeht, nachdem Jahrmillionen und aber Jahrmillionen hindurch, während der Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenzeit die bedeutendsten Anstrengungen übermenschlicher, das heißt göttlich-geistiger Wesen gemacht worden sind, um diesen physischen Leib herzustellen! Wir hätten also die sehr merkwürdige Tatsache vor uns, daß durch vier, oder meinetwillen durch drei planetarische Stufen hindurch, Saturn, Sonne, Mond, eine ganze Götterschar arbeitet an der Herstellung eines Weltelementes, wie es unser physischer Leib ist, und dieses Weltelement wäre dazu bestimmt, während der Erdenzeit jedesmal zu verschwinden, wenn ein Mensch stirbt. Es wäre ein sonderbares Schauspiel, wenn Maja — und ein anderes weiß ja die äußere Beobachtung da nicht — recht hätte.

Nun fragen wir uns: Kann Maja recht haben?

Zunächst scheint es ja allerdings, als wenn für diesen Fall die okkulte Erkenntnis der Maja recht gäbe; denn sonderbarerweise scheint die okkulte Beobachtung in diesem Falle mit der Maja übereinzustimmen. Wenn Sie durchgehen, was uns von der Geist-Erkenntnis geschildert wird als die Entwickelung des Menschen nach dem Tode, so wird in der Tat bei dieser Schilderung zunächst auf den physischen Leib kaum Rücksicht genommen. Es wird erzählt: der physische Leib wird abgeworfen, wird übergeben den Elementen der Erde. Dann wird erzählt von dem Ätherleib, von dem Astralleib, von dem Ich, und der physische Leib wird weiter nicht berücksichtigt, und es scheint, als ob durch das Schweigen der Geist-Erkenntnis der MajaErkenntnis recht gegeben wäre. So scheint es. Und es ist in einer gewissen Weise von der Geisteswissenschaft berechtigt, so zu sprechen, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil alles Weitere überlassen werden muß der tieferen Begründung der Christologie. Denn über das, was in bezug auf den physischen Leib über Maja hinausgeht, können wir gar nicht richtig sprechen, ohne daß vorher der Christus-Impuls und alles, was damit zusammenhängt, einmal in genügender Weise erklärt wird.

Wenn wir diesen physischen Leib zunächst einmal so betrachten, wie er in einem entscheidenden Momente vor dem Bewußtsein der Menschen dagestanden hat, so ergibt sich uns etwas ganz Merkwürdiges. Und da wollen wir einmal bei drei Völkerbewußtseinsarten, bei drei verschiedenen Formen des menschlichen Bewußtseins Anfrage halten, welches Bewußtsein man gehabt hat gerade in einer entscheidenden Epoche der Menschheitsentwickelung über alles, was mit unserem physischen Leibe zusammenhängt. Fragen wir zunächst einmal bei den Griechen an!

Wir wissen, daß die Griechen jenes bedeutsame Volk sind, das in der vierten nachatlantischen Kulturepoche seine richtige Entwickelungszeit hatte. Wir wissen, daß diese vierte nachatlantische Kulturepoche für uns zu beginnen hat etwa mit der Zeit des siebenten, achten, neunten Jahrhunderts vor unserer Zeitrechnung, und daß sie endet im dreizehnten, vierzehnten, fünfzehnten Jahrhundert unserer Zeitrechnung, nach dem Ereignisse von Palästina. Wir können ja auch leicht aus den äußeren Mitteilungen, Überlieferungen und Urkunden gerade in bezug auf diesen Zeitraum das, was eben gesagt worden ist, durchaus rechtfertigen. Wir sehen, daß die ersten, dämmerhaft klaren Nachrichten über das Griechentum kaum hinaufreichen über das sechste, siebente Jahrhundert vor unserer Zeitrechnung, während sagenhafte Nachrichten herunterkommen von noch früheren Zeiten her. Wir wissen aber auch, daß das, was die Größe der historischen Zeit des Griechentums ausmacht, noch hereinreicht aus der vorhergehenden Zeit, wo man es also dann mit der dritten nachatlantischen Kulturepoche auch im Griechentum zu tun hatte. So reichen Homers Inspirationen hinein in den Zeitraum, der dem vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum voranging; und Aeschylos, der so früh gelebt hat, daß eine Anzahl von seinen Werken ganz verlorengegangen ist, weist uns zurück auf die Mysteriendramatik, wovon er nur einen Nachklang bietet. So ragt herein die dritte nachatlantische Kulturperiode in das Griechenzeitalter; aber die vierte nachatlantische Kulturperiode kommt im Griechenzeitalter voll zum Ausdruck. Und wir müssen sagen: die wunderbare Griechenkultur ist der reinste Ausdruck des vierten nachatlantischen Kulturzeitalters. Da tönt uns denn ein merkwürdiges Wort aus diesem Griechentum herauf, ein Wort, das uns tief in die Seele desjenigen Menschen hineinschauen läßt, der ganz griechisch fühlte, das Wort des Heros: Lieber ein Bettler sein in der Oberwelt, als ein König im Reiche der Schatten! — Das ist ein Wort, das tiefe, tiefe Empfindungen der Griechenseele verrät. Man möchte sagen: Alles was uns auf der einen Seite erhalten ist aus der griechischen Zeit von klassischer Schönheit und klassischer Größe, von Ausgestaltung des Menschheitsideales in der Außenwelt, das alles tönt uns in einer gewissen Weise aus diesem Worte heraus. Da gedenken wir, wenn wir des Griechentums gedenken, jener wunderbaren Ausbildung des menschlichen Leibes in der griechischen Gymnastik, in den großen griechischen Wertspielen, welche karikaturenhaft in der Gegenwart nur ein solcher Mensch nachahmt, der nichts versteht von dem, was das Griechentum wirklich war. Daß eine jegliche Zeit ihre eigenen Ideale haben muß, das muß man berücksichtigen, wenn man verstehen will, wie diese Ausbildung des äußeren physischen Leibes, so wie er dasteht in seiner Form auf dem physischen Plan, ein besonderes Privileg des griechischen Geistes war; und wie weiterhin die Ausprägung des plastischen Kunstideals des Menschen, diese Steigerung der äußeren Menschengestalt in der Plastik, wieder ein Privileg des Griechentums sein mußte. Und wenn wir dazu die Ausgestaltung des menschlichen Bewußtseins ansehen, wie es zum Beispiel einen Perikles beherrschte, wo der Mensch auf der einen Seite nach dem allgemeinen Menschlichen sah und auf der anderen Seite wieder ganz auf seinen Füßen stand und sich wie ein Herr und König auf dem Erdboden innerhalb seines Stadtgebietes fühlte, — wenn wir alles das auf uns wirken lassen, dann müssen wir sagen: Die eigentliche Liebe war zugewendet der menschlichen Form, wie sie vor uns dastand auf dem physischen Plan, und auch die Ästhetik war zugewendet der Ausgestaltung dieser Form. Wo man so liebte und so das verstand, was vom Menschen auf dem physischen Plane steht, da konnte man sich auch dem Gedanken hingeben: Wenn das, was dem Menschen diese schöne Form auf dem physischen Plane gibt, abgenommen wird der menschlichen Natur, dann bleibt ein Rest, den man nicht so hoch schätzen kann wie das, was einem im Tode genommen wird! Diese höchste Liebe zur äußeren Form führte notwendig dazu, mit einem pessimistischen Blick anzuschauen, was vom Menschen übrig bleibt, wenn er durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten ist. Und wir können es an der griechischen Seele voll verstehen, daß dasselbe Auge, das mit so großer Liebe auf die äußere Form blickte, sich traurig fühlte, wenn die Seele denken mußte: Diese Form wird weggenommen der menschlichen Individualität, und die menschliche Individualität lebt ohne diese Form weiter! Nehmen wir das, was so sich zugetragen hat, zunächst nur in dieser gefühlsartigen Weise, dann müssen wir sagen: Wir haben im Griechentum dasjenige Menschentum, das die äußere Form des physischen Leibes am meisten liebte und schätzte und alle Traurigkeit durchmachte, die bei seinem Untergange im Tode durchgemacht werden konnte.

Und jetzt betrachten wir ein anderes Bewußtsein, das sich ungefähr zur selben Zeit entwickelte. Betrachten wir einmal das BuddhaBewußtsein, das dann von Buddha in seine Bekenner übergegangen ist. Da haben wir ungefähr das Gegenteil des Griechentums vor uns. Wir brauchen uns ja nur des einen zu erinnern: der Nerv der vier großen Wahrheiten des Buddha ist ja damit gegeben, daß gesagt wird, die menschliche Individualität wird in dieses Dasein, in dem es umschlossen ist von der äußeren physischen Form, durch die Begierde zum Dasein hereingebracht. In was für ein Dasein? In ein Dasein, dem gegenüber die Buddha-Lehre sagen muß: Geburt ist Leiden, Krankheit ist Leiden, Alter ist Leiden, Tod ist Leiden! Es liegt in diesem Nerv des Buddhismus, sich zu sagen: Durch alles, wodurch wir umschlossen werden von einer äußeren körperlichen Hülle, wird unsere Individualität, die aus göttlich geistigen Höhen herabkommt mit der Geburt, und die wieder hinaufgeht in göttliche Höhen, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des "Todes schreitet, durch alles das wird diese Individualität dem Schmerz des Daseins, dem Leid des Daseins ausgeliefert; und es kann im Grunde genommen nur ein Heil geben für den Menschen, das in den vier großen heiligen Wahrheiten des Buddha ausgedrückt wird, um frei zu werden von dem äußeren Dasein, abzuwerfen die äußere Hülle, das heißt: soweit die Individualität umzugestalten, daß sie baldmöglichst in der Lage ist, alles abzuwerfen, was äußere Hülle ist. Wir merken also: hier ist die umgekehrte Empfindung tätig von dem, wie der Grieche empfand. Ebenso stark, wie der Grieche geliebt und geschätzt hat die äußere körperliche Hülle und traurig empfunden hat das Abwerfen dieser körperlichen Hülle, ebenso gering schätzte der Buddha-Bekenner diese körperliche Hülle und betrachtete sie als das, was so schnell als möglich abgeworfen werden muß. Und damit war verbunden, daß der Drang nach Dasein, das von einer äußeren Körperhülle umschlossen ist, bekämpft wird.

Und jetzt gehen wir noch ein wenig tiefer gerade in diese BuddhaGedanken ein. Da tritt uns entgegen, was im Buddhismus als eine Art theoretischer Anschauung vorhanden ist über die aufeinanderfolgenden Inkarnationen des Menschen. Es handelt sich dabei nun weniger darum, was der einzelne denkt über die Theorie des Buddha, als um das, was in das Bewußtsein der buddhistischen Bekenner eingedrungen ist. Das habe ich auch schon öfter charakterisiert. Ich habe gesagt: Man hat vielleicht keine bessere Gelegenheit, nachzufühlen, was ein Bekenner des Buddhismus fühlen mußte gegenüber den fortlaufenden Inkarnationen des Menschen, als wenn man sich vertieft in jene Rede, welche uns überliefert ist als die Rede des Königs Milinda mit einem buddhistischen Weisen. Da wird der König Milinda von dem buddhistischen Weisen Nagasena darüber belehrt, daß, wenn er zu Wagen gekommen sei, er bedenken solle, ob der Wagen außer den Rädern, der Deichsel, dem Wagenkasten, dem Sitz und so weiter noch irgend etwas habe. «Bist du gekommen in deinem Wagen, so bedenke, o großer König», sagt der Weise Nagasena zum König, «daß alles, was du im Wagen vor dir hast, nichts anderes ist als die Räder, die Deichsel, der Wagenkasten, der Sitz — und nichts ist außerdem vorhanden als ein Wort, das zusammenfaßt die Räder, Deichsel, Wagenkasten, Sitz und so weiter. Du kannst also nicht von einer besonderen Individualität des Wagens sprechen; sondern du mußt dir klar sein, daß Wagen ein leeres Wort ist, wenn du an etwas anderes denkst als an seine Teile, seine Glieder.» Und noch ein anderes Gleichnis wählt Nagasena, der Weise, dem König Milinda gegenüber. «Betrachte die Mandelfrucht, die auf dem Baume wächst», sagte er, «und bedenke, daß aus einer anderen Frucht ein Same genommen ist, der in die Erde gelegt und verfault ist; daraus ist der Baum gewachsen und darauf die Mandelfrucht. Kannst du sagen, daß die Frucht auf dem Baume etwas anderes gemeinsam hat als Name und äußere Form mit jener Frucht, die als Same genommen, in die Erde gelegt und verfault ist?» — So viel, will Nagasena sagen, hat der Mensch gemeinsam mit dem Menschen seiner vorhergehenden Inkarnation, wie die Mandelfrucht auf dem Baume mit der Mandelfrucht, die als Same in die Erde gelegt ist; und wer da glaubt, daß das, was als Mensch vor uns steht, was mit dem Tode hinweggeweht wird, irgend etwas anderes sei als Name und Form, der glaubt etwas ebenso Falsches als der, der da glaubt, daß in dem Wagen — in dem Namen Wagen — etwas anderes enthalten ist als die Teile des Wagens: Räder, Deichsel und so weiter. Von der vorherigen Inkarnation geht in die neue Inkarnation nicht so etwas über, wie es der Mensch mit seinem Ich benennt.

Das ist wichtig! Und es ist immer wieder und wieder zu betonen: es kommt nicht darauf an, wie es dem einen oder dem anderen einfällt, dieses oder jenes Wort Buddhas zu interpretieren, sondern wie der Buddhismus im Bewußtsein der Bevölkerung gewirkt hat, was er den Seelen gegeben hat! Und was er den Seelen gegeben hat, das ist eben ungeheuer klar und bedeutsam mit diesem Gleichnis ausgedrückt, das uns von dem König Milinda und dem buddhistischen Weisen überliefert ist. Was wir das Ich nennen, und wovon wir sagen, daß es gefühlt und empfunden wird zunächst vom Menschen, wenn er auf sein Inneres reflektiert, von dem sagt der Buddhist: Es ist im Grunde genommen etwas, was dahinfließt, und was der Maja angehört, ebenso wie alles andere, was nicht von einer Inkarnation in die andere geht.

Ich habe schon einmal erwähnt: ein christlicher Weiser, der zu parallelisieren wäre mit dem buddhistischen Weisen, würde anders zu dem König Milinda gesprochen haben. Der buddhistische Weisesagte zu dem König: Betrachte dir den Wagen! Räder, Deichsel und so weiter, das sind die Teile des Wagens, und über diese Teile hinaus ist «Wagen» nur Name und Form. Du hast nichts Reales gegeben in dem Wagen mit dem Namen Wagen; sondern wenn du zum Realen gehen willst, mußt du die Teile nennen. — Der christliche Weise würde über denselben Fall in folgender Art gesprochen haben: O weiser König Milinda, du bist zu Wagen gekommen. Sieh dir an den Wagen: du kannst an dem Wagen nur sehen die Räder, die Deichsel, den Wagenkasten und so weiter. Aber ich frage dich einmal: Kannst du mit den bloßen Rädern hierher fahren?, kannst du mit der bloßen Deichsel hierher fahren?, kannst du mit dem bloßen Sitz hierher fahren? und so weiter. Du kannst also auf allen Teilen nicht hierher fahren! Sofern sie Teile sind, machen sie den Wagen; aber auf den Teilen kannst du nicht hierherkommen. Wenn aber die Teile zusammen den Wagen ausmachen, so ist noch etwas anderes notwendig, als daß sie Teile sind. Das ist zunächst für den Wagen der ganz bestimmte Gedanke, der Räder, Deichsel, Wagenkasten und so weiter zusammenfügt. Und der Gedanke des Wagens ist etwas ganz Notwendiges, was du zwar nicht sehen kannst, was du aber darum doch anerkennen mußt! — Und der Weise würde dann übergehen auf den Menschen und sagen: Von dem einzelnen Menschen kannst du nur sehen den äußeren Leib, die äußeren Taten und die äußeren seelischen Erlebnisse; du siehst aber an dem Menschen so wenig sein Ich, wie du den Namen Wagen an seinen einzelnen Teilen siehst. Aber wie etwas ganz anderes in den Teilen begründet ist, — nämlich das, was dich hierher fahren läßt, so ist auch beim Menschen in allen seinen Teilen etwas ganz anderes begründet, nämlich das, was das Ich ausmacht. Das Ich ist etwas Reales, was als ein Übersinnliches von Inkarnation zu Inkarnation geht.

Wie müssen wir uns etwa das Schema der buddhistischen Reinkarnationslehre denken, wenn es entsprechend der bloß buddhistischen Theorie dargestellt werden soll?

Mit dem Kreis wollen wir zeichnen die Erscheinung eines Menschen zwischen Geburt und 'Tod. Der Mensch stirbt. Der Zeitpunkt seines Sterbens sei mit der Linie AB angedeutet. Was bleibt nun übrig von allem, das in das gegenwärtige Dasein zwischen Geburt und Tod hineingebannt ist? Eine Summe von Ursachen, die Ergebnisse der Taten, alles was der Mensch Gutes oder Böses, Schönes oder Häßliches, Gescheites oder Dummes getan hat, bleibt übrig. Was da übrig bleibt, wirkt als Ursachen weiter und bildet einen Ursachenkern C für die nächste Inkarnation. Da herum gliedern sich in der nächsten Inkarnation D neue Leibeshüllen; die erleben neue Tatsachen, neue Erlebnisse gemäß diesem früheren Ursachenkern. Es bleibt dann von diesen Erlebnissen und so weiter wieder ein Kern von Ursachen E für die folgende Inkarnation, die das, was von der früheren Inkarnation in sie hereinragt, umschließen kann, und das dann mit dem, was als etwas ganz Selbständiges während dieser Inkarnation hinzukommt, wieder den Ursachenkern für die nächste Inkarnation bildet und so fort. Das heißt: es erschöpft sich das, was durch die Inkarnationen hindurchgeht, in Ursachen und Wirkungen, die, ohne daß ein gemeinschaftliches Ich die Inkarnationen zusammenhält, von einer Inkarnation in die andere hinüberwirken. Wenn ich mich also in dieser Inkarnation mit «Ich» nenne, ist das nicht aus dem Grunde, weil dasselbe Ich auch in der vorhergehenden Inkarnation da war, denn von der vorherigen Inkarnation ist nur das vorhanden, was die karmischen Resultate sind, und was ich mein Ich nenne, ist nur eine Maja der gegenwärtigen Reinkarnation.

Wer den Buddhismus wirklich kennt, muß ihn in dieser Weise darstellen; und er muß sich klar sein, daß das, was wir das Ich nennen, gar keinen Platz hat innerhalb des Buddhismus.

Nun gehen wir aber zu dem, was wir wissen aus der anthroposophischen Erkenntnis: Wodurch ist denn der Mensch überhaupt imstande geworden sein Ich auszubilden? Durch die Erdenentwickelung! Und erst im Laufe der Erdenentwickelung ist der Mensch dazu gekommen, sein Ich auszubilden. Es kam hinzu zu seinem physischen Leib, Ätherleib und Astralleib auf der Erde sein Ich. Nun wissen wir, wenn wir uns erinnern an alles, was wir zu sagen hatten über die Entwickelungsphasen des Menschen während der Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenzeit, daß noch während der Mondenzeit der menschliche physische Körper eine ganz bestimmte Form nicht hatte, daß er erst auf der Erde diese Form erhalten hat. Daher sprechen wir auch von dem Erdendasein als derjenigen Epoche, in welcher die Geister der Form erst eingriffen und den physischen Leib des Menschen so umgestalteten, daß er jetzt seine Form hat. Diese Formung des menschlichen physischen Leibes war aber notwendig, damit das Ich Platz greifen konnte im Menschen, damit das, was als physischer Erdenleib geformt der physischen Erde gegenübersteht, die Grundlage bietet für die Entstehung des Ich, wie wir es kennen. Wenn wir das bedenken, wird uns das Folgende nicht mehr unbegreiflich erscheinen.

Wir haben in bezug auf die Schätzung des Ich bei den Griechen davon gesprochen, daß dieses Ich seinen äußeren Ausdruck in der äußeren Menschenform findet. Gehen wir jetzt zum Buddhismus über, und erinnern wir uns, daß der Buddhismus mit seiner Erkenntnis die äußere Form des menschlichen physischen Leibes möglichst rasch abwerfen und überwinden will. Können wir uns da noch verwundern, daß wir bei ihm keine Schätzung dessen finden, was mit dieser Form des physischen Leibes zusammenhängt? So wenig, wie aus dem innersten Nerv des Buddhismus heraus die äußere Form des physischen Leibes geschätzt wird, so wenig wird die äußere Form, die das Ich braucht, um zum Dasein zu kommen, geschätzt, — ja, sogar vollständig abgelehnt. Der Buddhismus hat also die Form des Ich verloren durch die Art, wie er die Form des physischen Leibes schätzte.

So sehen wir, wie diese zwei Geistesströmungen einander polarisch gegenüberstehen: das Griechentum, von dem wir fühlen, daß es die äußere Form des physischen Leibes als die äußere Form des Ich am höchsten schätzte, und der Buddhismus, der da verlangt, daß die äußere Form des physischen Leibes mit allem Drang nach Dasein möglichst bald überwunden wird, und der daher in seiner Theorie das Ich vollständig verloren hat.

Zwischen diesen beiden einander entgegengesetzten Weltanschauungen steht das althebräische Altertum mitten drinnen. Dieses ist weit davon entfernt, von dem Ich so gering zu denken, wie etwa der Buddhismus. Sie brauchen sich nur zu erinnern, daß es innerhalb des Buddhismus eine Ketzerei ist, ein fortlaufendes Ich von einer Inkarnation zur nächsten Inkarnation anzuerkennen. Aber das althebräische Altertum hält es sehr stark mit dieser Ketzerei. Und es wäre keinem Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums in den Sinn gekommen, daß das, was im Menschen lebt als sein eigentlicher göttlicher Funke — womit er seinen Ich-Begriff verbindet — sich verliert, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes geht. Wenn wir uns klarmachen wollen, wie der Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums zu der Sache stand, so müssen wir sagen: Er fühlt sich in seinem Innern mit der Gottheit verbunden, innig verbunden; er weiß, daß er gleichsam mit den besten Fäden seines Seelenlebens an dem Wesen dieser Gottheit hängt. So ist der Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums in bezug auf den Ich-Begriff weit verschieden von dem buddhistischen Bekenner, aber er ist auf der anderen Seite auch weit verschieden von dem Griechen. Wenn man das ganze Altertum durchgeht: jene Schätzung der Persönlichkeit und damit auch jene Schätzung der äußeren menschlichen Form, wie sie dem Griechen eigen ist, ist im hebräischen Altertum nicht vorhanden. Für den Griechen wäre es schlechterdings ein absoluter Unsinn gewesen zu sagen: Du sollst dir von deinem Gotte kein Bild machen! Das würde er nicht verstanden haben, wenn ihm jemand gesagt hätte: Du sollst dir von deinem Zeus, von deinem Apollo und so weiter kein Bild machen! Denn er hatte das Gefühl, daß das Höchste die äußere Form ist, und daß das Höchste, was der Mensch den Göttern antun kann, das ist, sie mit dieser von ihm geschätzten menschlichen Form zu bekleiden; und nichts wäre ihm absurder vorgekommen als ein Gebot: Du sollst dir von dem Gotte kein Bild machen! Seine Menschheitsform gab der Grieche als Künstler auch seinen Göttern. Und um das wirklich zu werden, was er sich dachte — ein Ebenbild der Gottheit —, dazu führte er seine Kämpfe, übte seine Gymnastik und so weiter, um so recht ein Abbild des Gottes zu werden.

Das althebräische Altertum hatte aber das Gebot: Du sollst dir kein Bild machen von dem Gotte! aus dem Grunde, weil der Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums die äußere Form nicht so schätzte wie die Griechen, weil er sie für unwürdig gehalten hätte dem Wesen der Göttlichkeit gegenüber. So weit also der Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums auf der einen Seite entfernt war von dem Anhänger des Buddhismus, der am liebsten die menschliche Form beim Durchschreiten des Todes ganz abgestreift hätte, so weit war er auf der anderen Seite entfernt von dem Griechen. Er war darauf bedacht, daß diese Form gerade zum Ausdruck brachte, was die Gebote, die Gesetze der göttlichen Wesenheit sind, und er war sich klar, daß der, welcher ein «Gerechter» war, in den folgenden Generationen durch die Geschlechter fortpflanzte, was er als Gerechtes gesammelt hatte. Nicht die Auslöschung der Form, sondern die Fortpflanzung der Form durch die Geschlechter war es, was dem Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums vor Augen stand. Als ein drittes stand also die Ansicht eines Anhängers des althebräischen Volkes mitten drinnen zwischen der Anschauung des Buddhisten, der die Wertung des Ich verloren hatte, und dem Griechen, der in der Leibesform das Höchste sah, und der es als traurig empfand, wenn die Leibesform mit dem "Tode verschwinden mußte.

So standen sich die drei Anschauungen gegenüber. Und um das althebräische Altertum noch besser zu verstehen, müssen wir uns klarmachen, daß dem Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums das, was er als sein Ich schätzte, zugleich das göttliche Ich in einer gewissen Beziehung war. Der Gott lebte weiter in der Menschheit, lebte in dem Menschen drinnen. Und in der Verbindung mit dem Gotte fühlte der alte Hebräer zugleich sein Ich. So war das Ich, das er fühlte, zusammenfallend mit dem göttlichen Ich. Das göttliche Ich trug ihn; das göttliche Ich war aber auch wirksam in ihm. Sagte der Grieche: Ich schätze mein Ich so stark, daß ich nur mit Schaudern hinschaue auf das, was mit dem Ich nach dem Tode wird!, sagte der Buddhist: Es soll möglichst bald das, was die Ursache der äußeren Form des Menschen ist, abfallen von dem Menschen!, so sagte der Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums: Ich bin mit dem Gotte verbunden; es ist mein Schicksal. Und solange ich mit ihm verbunden bin, trage ich mein Schicksal. Ich kenne nichts anderes als die Identifizierung meines Ich mit dem göttlichen Ich! In dieser Denkweise des alten Judentums, weil sie in der Mitte steht zwischen Griechentum und Buddhismus, liegt nicht wie im Griechentum selbst von vornherein die Anlage zur Tragik gegenüber der Erscheinung des Todes, sondern diese Tragik liegt in einer mittelbareren Weise darin. Und wenn es echt griechisch ist, daß der Heros sagt: Lieber ein Bettler sein in der Oberwelt — das heißt mit der menschlichen Leibesform — als ein König im Reich der Schatten —, so hätte der Bekenner des althebräischen Altertums dies nicht ohne weiteres sagen können. Denn er weiß, wenn im Tode seine Leibesform abfällt, bleibt er mit dem Gotte verbunden. Einfach durch die Tatsache des Todes kann er nicht in tragische Stimmung verfallen. Dennoch ist — wenn auch mittelbar — die Anlage zur Tragik im althebräischen Altertum vorhanden, und sie ist ausgedrückt in der wunderbarsten dramatischen Erzählung, die im Altertum überhaupt geschrieben worden ist, in der Hiob-Erzählung.

Da sehen wir, wie das Ich des Hiob sich angeknüpft fühlt an seinen Gott und in Konflikt kommt mit seinem Gott — aber auf andere Art, als das griechische Ich in Konflikt kommt. Da wird uns geschildert, wie über Hiob hereinbricht Unglück über Unglück, trotzdem er sich bewußt ist, daß er ein gerechter Mann ist und alles getan hat, was aufrechterhalten kann den Zusammenhang seines Ich mit dem göttlichen Ich. Und während es schien, daß sein Dasein gesegnet ist und gesegnet sein mußte, bricht das tragische Schicksal herein. Er ist sich keiner Sünde bewußt; er ist sich bewußt, daß er getan hat, was ein Gerechter gegenüber seinem Gotte tun muß. Da wird ihm angekündigt, daß zerstört ist all sein Hab und Gut, getötet seine ganze Familie; da wird er selbst in bezug auf seinen äußeren Leib, diese göttliche Form, mit schwerer Krankheit und Drangsal belegt. Da steht er, der sich bewußt ist: Was in mir mit meinem Gotte zusammenhängt, das hat sich bemüht, gerecht zu sein gegenüber seinem Gotte, und mein von diesem Gotte verhängtes Schicksal ist das, was mich hereingestellt hat in die Welt. Dieses Gottes Taten, sie haben mich so schwer getroffen! Und da steht sein Weib neben ihm und fordert ihn auf mit eigentümlichem Worte, seinem Gotte abzusagen. Diese Worte sind richtig überliefert. Was da sein Weib spricht, ist eines von denjenigen Worten, die unmittelbar dem entsprechen, was auch die Akasha-Chronik sagt: «Sage deinem Gotte ab, da du so leiden mußt, da er diese Leiden über dich gebracht hat, und stirb!» Wieviel Unendliches liegt in diesen Worten: Verliere das Bewußtsein des Zusammenhanges mit deinem Gotte; dann fällst du heraus aus dem göttlichen Zusammenhange, fällst ab wie ein Blatt vom Baum, und dein Gott kann dich nicht mehr strafen! — Das Verlieren des Zusammenhanges mit dem Gotte ist aber zugleich der Tod! Denn solange sich das Ich zusammenhängend fühlt mit dem Gotte, kann der "Tod es nicht erreichen. Es muß sich von dem Zusammenhange mit dem Gotte abreißen; dann kann der Tod es erst erreichen. Der äußere Schein spricht so, daß im Grunde genommen alles gegen den Gerechten Hiob ist; seine Frau sieht die Leiden, rät ihm dazu, dem Gotte abzusagen und zu sterben; seine Freunde kommen und sagen, du mußt das und das getan haben; denn Gott straft keinen Gerechten! Er ist sich aber bewußt, daß das, was sein persönliches Bewußtsein umfaßt, keine Ungerechtigkeit getan hat. Er steht so durch das, was ihm in der äußeren Welt entgegentritt, vor einer ungeheuren Tragik, vor der Tragik des Nichtverstehenkönnens der ganzen menschlichen Wesenheit, des Sichverbundenfühlens mit dem Gotte und des Nichtverstehens, wie aus dem Gotte das fließen kann, was er erlebt.

Denken wir uns das in aller Stärke auf eine menschliche Seele abgelagert, und denken wir uns jetzt aus dieser Seele hervorbrechend die Worte, die uns aus der Hiob-Überlieferung erzählt sind: «Ich weiß, daß mein Erlöser lebt! Ich weiß, daß ich einmal wieder umkleidet sein werde mit meinem Gebein, mit meiner Haut — und anschauen werde den Gott, mit dem ich zusammen bin!» — Dieses Bewußtsein der Unzerstörbarkeit der menschlichen Individualität bricht hervor trotz alles Leides und aller Schmerzen aus Hiobs Seele. So stark ist das Ich-Bewußtsein als Inneres in dem althebräischen Bekenntnis enthalten. Aber etwas höchst Merkwürdiges tritt uns da entgegen. «Ich weiß, daß mein Erlöser lebt!» — sagt Hiob — «Ich weiß, daß ich einstmals wieder umgeben sein werde mit meiner Haut und aus meinen Augen sehen werde die Herrlichkeit meines Gottes!» Mit dem Erlöser-Gedanken bringt Hiob in Zusammenhang den äußeren Leib, Haut und Gebein, Augen, die physisch sehen. Sonderbar: plötzlich tritt uns gerade in diesem, zwischen Griechentum und Buddhismus mitten drinnen stehenden althebräischen Bewußtsein ein Bewußtsein von der Bedeutung der physischen Leibesform entgegen im Zusammenhange mit dem Erlöser-Gedanken, der dann der Grund und Boden geworden ist für den Christus-Gedanken! Und wenn wir die Antwort des Weibes des Hiob nehmen, fällt noch mehr Licht auf die ganze Aussage des Hiob. «Sage deinem Gotte ab und stirb!», das heißt: wer also nicht seinem Gotte absagt, der stirbt nicht. Das liegt in diesen Worten. Was heißt denn aber sterben? Sterben heißt, den physischen Leib abwerfen. Die äußere Maja scheint zu sagen, daß der physische Leib in die Elemente der Erde übergeht und sozusagen verschwindet. In der Antwort der Frau des Hiob liegt also: Mache, was nötig ist, damit dein physischer Leib verschwindet. — Denn anders könnte es nicht heißen; sonst könnten die nachfolgenden Worte des Hiob keinen Sinn haben. Dann allein kann man so etwas verstehen, wenn man das, wodurch uns der Gott hineinversetzt hat in die Welt, verstehen kann: nämlich die Bedeutung des physischen Leibes. Hiob selber aber sagt — denn das liegt wieder in seinen Worten: O ich weiß ganz genau, ich brauche nicht das zu tun, was meinen physischen Leib völlig verschwinden läßt, was nur der äußere Schein darbietet. Es gibt eine Möglichkeit, daß das gerettet werden kann dadurch, daß mein Erlöser lebt — was ich nicht anders als mit den Worten zusammenfassen kann: Ich werde einmal regeneriert zusammenhaben meine Haut, mein Gebein und werde mit meinen Augen sehen die Herrlichkeit meines Gottes; ich werde erhalten können die Gesetzmäßigkeit meines physischen Leibes; aber dazu muß ich das Bewußtsein haben, daß mein Erlöser lebt!

So tritt uns in dieser Hiob-Erzählung, zum ersten Male, möchte man sagen, ein Zusammenhang entgegen zwischen der physischen Leibesform — was der Buddhist abstreifen möchte, was der Grieche abfallen sieht und darüber Trauer empfindet — und dem IchBewußtsein. Es tritt uns zum ersten Male etwas entgegen wie eine Aussicht auf eine Rettung dessen, was die Schar der Götter von dem alten Saturn, Sonne und Mond bis zur Erde herein als die physische Leibesform hervorgebracht hat und was notwendig macht, wenn es erhalten werden soll, wenn man von ihm sagen soll, daß es ein Resultat hat, was uns in Knochen, Haut und Sinnesorganen gegeben ist, daß man das andere dazufügt: Ich weiß, daß mein Erlöser lebt!

Sonderbar, — so könnte jemand nach dem jetzt Gesagten die Frage aufwerfen — geht etwa aus der Hiob-Erzählung hervor, daß der Christus die Toten auferwecke, die Leibesform rette, von der die Griechen glaubten, daß sie verschwinden würde? Und liegt vielleicht darin etwa, daß es nicht richtig ist, im vollen Sinne des Wortes, für die Gesamtentwickelung der Menschheit, daß die äußere Leibesform ganz verschwindet? Wird sie etwa einverwoben dem ganzen Entwickelungsprozeß der Menschheit? Spielt das eine Rolle in der Zukunft, und hängt das mit der Christus-Wesenheit zusammen?

Diese Frage wird uns aufgegeben. Und da kommen wir dazu, das, was wir in der Geisteswissenschaft bisher gehört haben, in einer gewissen Weise zu erweitern. Wir hören, daß, wenn wir durch die Pforte des Todes gehen, wir den Ätherleib wenigstens beibehalten, den physischen Leib aber ganz abstreifen, ihn äußerlich den Elementen ausgeliefert sehen. Aber seine Form, an der durch Jahrmillionen und Jahrmillionen gearbeitet worden ist, geht sie wesenlos verloren oder wird sie in einer gewissen Weise erhalten?

Diese Frage betrachten wir als das Resultat der heutigen Auseinandersetzung und treten morgen an die Frage heran: In welchem Verhältnisse steht der Impuls des Christus für die Menschheitsentwickelung zu der Bedeutung des äußeren physischen Leibes, der durch die ganze Erdentwickelung dem Grabe, dem Feuer oder der Luft übergeben worden ist, und der in seiner Erhaltung in bezug auf seine Form für die Zukunft der Menschheit nötig ist?

Fifth Lecture

When you consider that our lectures have shown that the Christ impulse must be regarded as the most profound in the evolutionary processes of humanity, you will undoubtedly find it self-evident that some effort of our mental powers is necessary in order to understand the full meaning and entire scope of this Christ impulse. It is certainly a widespread misconception that what is highest in the world must be comprehensible in the simplest possible way, and that if someone is compelled to speak in a complicated manner about the sources of existence, this must be rejected on the grounds that truth must be simple. Ultimately, it is certainly simple. But if we want to get to know the highest on a certain level, it is not difficult to see that we must first make a journey in order to understand the highest. And so we will again have to gather together many things in order to find our way, from a certain point of view, into the whole greatness and meaning of the Christ impulse.

We need only open the letters of Paul and we will soon find that Paul — whom we know tried to incorporate precisely the supersensible aspect of the Christ being into human development — that Paul drew upon the entire development of humanity, so to speak, in order to arrive at the concept, the idea of Christ. However, when we allow Paul's letters to work on us, we ultimately find ourselves faced with something that makes a most significant impression through its tremendous simplicity and the profound poignancy of its words and sentences. But this is only because Paul himself, through his own initiation, worked his way up to that simplicity which cannot be the starting point of truth, but only its consequence, its goal. If we now want to penetrate what Paul ultimately expresses about the Christ being in wonderfully monumental, simple words, we will have to approach, in our spiritual scientific way, an understanding of human nature, for whose further development the Christ impulse came to Earth.

Let us therefore consider what we already know about human nature as it appears to the occult gaze! We divide human life into two parts, which we consider in relation to the passage of time: the time between birth or conception and death, and the time that elapses between death and a new birth. When we first place the human being before us as he stands before us in physical life, we know that the occult view sees him as a fourfold being, but as a fourfold being in the process of development: the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and the I. And we know that in order to understand human development, we must familiarize ourselves with the occult truth that this I — which we become aware of in our feelings and sensations when we simply disregard the external world and try to live within ourselves — that this I, from the occult point of view, passes from incarnation to incarnation. But we also know that this I is, as it were, enveloped — although “enveloped” is not a good expression, but we can use it for the time being — by the three other members of human nature, the astral body, the etheric body, and the physical body. We know that the astral body is, in a certain sense, a companion of the I through the various incarnations. Even though much of the astral body must be shed during the Kamaloka period, this astral body remains with us throughout the incarnations as a kind of force body that holds together what we have stored within ourselves in terms of moral, intellectual, and aesthetic progress during an incarnation. What real progress is, is held together by the power of the astral body, carried from one incarnation to another and, as it were, joined together with the ego, which as the fundamental eternal element in us passes from incarnation to incarnation. And we know further that although much is stripped away from the etheric body immediately after death, an extract of this etheric body remains with us, which we take with us from one incarnation to the next. It is indeed the case that in the first days immediately after death we have a kind of review, like a large tableau, of our previous life, and that we take the summary of this review — the extract — with us as an etheric result. The rest of the etheric body is handed over to the general etheric world in one form or another, depending on the development of the individual human being. When we turn our gaze to the fourth member of the human being, the physical body, it initially appears as if this physical body simply disappears into the physical world. This can even be proven externally in the physical world, for this physical body is, in one way or another, subjected to decomposition, as far as the external eye can see. The question is simply this — and everyone who is concerned with spiritual science should ask themselves this question: Is perhaps everything that our external physical knowledge can tell us about the fate of our physical body Maya? And the answer is not so far-fetched for those who have begun to understand spiritual science. Once you have begun to understand spiritual science, you say to yourself: Everything that the senses offer is Maya, is external illusion. How can you still expect it to be really true, even if it imposes itself so crudely, that the physical body disappears without a trace when it is committed to the grave or to fire? Perhaps something much deeper is hidden behind the outer Maya that imposes itself on the senses!