From Jesus to Christ

GA 131

10 October 1911, Karlsruhe

Lecture VI

By taking our start from what was said yesterday, we shall be able to come nearer to the fundamental questions of Christianity and to penetrate into its essential nature. We shall see that only by this means can we see into the heart of what the Christ-Impulse has become for the evolution of humanity and what it will become in the future.

People are always insisting that the answers to the highest questions must not be complicated; the truth must be brought directly to each person in the simplest way. In support of this they argue, for example, that the Apostle John in his last years expressed the quintessence of Christianity in words of truth: ‘Children, love one another.’ No one, however, should conclude that a person who simply pronounces the words, ‘Children, love one another’, knows the essence of Christianity and of all truth for men. Before the Apostle John was entitled to pronounce these words, he had fulfilled various preconditions. We know it was at the end of a long life, in his ninety-fifth year, that he came to this utterance; only by then, in that particular incarnation, had he earned the right to use such words, Indeed, he stands there as a witness that this saying, if it came from any chance individual, would not have the power it had from him. For he had achieved something else, also. Although the critics dispute it, he was the author of the John Gospel, the Apocalypse, and the Epistles of John. Throughout his life he had not always said, ‘Children, love one another!’ He had written a work which belongs to the most difficult productions of man, the Apocalypse, and the John Gospel, which penetrates most intimately and deeply into the human soul. He had gained the right to pronounce such a saying only through a long life and through what he had accomplished. If anyone lives a life such as his, and does what he did, and then says, as he did, ‘Children, love one another!’ there are no grounds for objecting to it. We must, however, be quite clear that although some things can be compressed into a few words, so that these few words signify very much, the same few words may also say nothing. Many a person who pronounces a word of wisdom which in its proper setting would perhaps signify something very deep, believes that by merely uttering it he has said a very great deal.

The writer of the Apocalypse and of the John Gospel, in his greatest age, could speak the words ‘Children, love one another!’ out of the essence of Christianity, but the same words from the mouth of another person may be a mere phrase. We must gather matters for the understanding of Christianity from far a field, so that we may apply them to the simplest truths of daily life.

Yesterday we had to approach the question, so fateful for modern thought: What are we to make of the physical body in relation to the four-fold being of man?

We shall see how the points brought out yesterday in looking at the differing views of the Greeks, the ancient Hebrews and the Buddhists will lead us further towards understanding the nature of Christianity. But if we are to learn more concerning the fate of the physical body, we must first take up a question which is central to the whole Christian cosmic conception; a question which lies at the very core of Christianity: How it is with the Resurrection of Christ? Must we not assume that for the understanding of Christianity it is essential to reach an understanding of the Resurrection?

To see how important this is, we need only recall a passage in the first Epistle of Paul to the Corinthians, (I Corinthians 15:14–20):

If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain, and your faith is in vain. We are even found to be misrepresenting God, because we testified of God that he raised Christ, whom he did not raise if it is true that the dead are not raised. For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If in this life we who are in Christ have only hope, we are of all men most to be pitied. But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep.

(Quotations from the New Testament are in the Revised Standard Version, 1946.)

We must remember that Christianity, in so far as it has extended over the world, began with Paul. And if we are disposed to take these important words seriously, we cannot simply pass them over by saying that we must leave the question of the Resurrection unexplained. For what is it that Paul says? That the whole of Christianity has no justification, and the whole Christian Faith no meaning, if the Resurrection is not true! That is what is said by Paul, with whom Christianity as a fact of history had its starting-point. And it means that anyone who is willing to give up the Resurrection must give up Christianity as Paul understood it.

And now let us pass over almost two thousand years and ask people of the present day how, according to the requirements of modern culture, they stand with regard to the question of the Resurrection. I shall not now take note of those who simply deny Jesus entirely; it is naturally quite easy for them to be clear regarding the question of the Resurrection. If Jesus never lived, one need not trouble about the Resurrection. Leaving such persons aside, we will turn to those who about the middle or in the last third of the nineteenth century had accepted the current ideas of our time—the time in which we are still living. We will ask them what they think, in conformity with the whole culture of our day, concerning the question of the Resurrection.

We will take a man who has gained great influence over the way of thinking of those who consider themselves best informed—David Friedrich Strauss. In his work on Reimarus, a thinker of the eighteenth century, we read: ‘The Resurrection of Jesus is really a shibboleth, concerning which not only the various conceptions of Christianity, but the various world-philosophies and stages of spiritual evolution, are at variance.’ And in a Swiss journal almost of the same date we read: ‘As soon as I can convince myself of the reality of the Resurrection of Christ, this absolute miracle, I tear down the modern conception of the world. This breach in what I believe to be the inviolable order of Nature would make an irreparable rent in my system, in my whole thought-world.’

Let us ask how many persons of our present time who, according to the modern standpoint, must and do subscribe to these words, would say, ‘If I were obliged to recognise the Resurrection as historical fact, I would tear down my whole system of thought, philosophical or otherwise.’ Let us ask how should the Resurrection, as historical fact, fit in with a modern man's outlook on the world.

Let us recall something indicated in my first public lecture on this subject, that the Gospels are to be taken first and foremost as Initiation writings. The leading events depicted in the Gospels are fundamentally Initiation events—events which had formerly taken place within the secret places of the temples of the Mysteries, when this or that person, who had been deemed worthy, was initiated by the hierophants. Such a person, after he had been prepared for a long time, went through a kind of death and a kind of resurrection. He had also to go through certain situations in life which reappear for us in the Gospels—in the story of the Temptation, the story set on the Mount of Olives, and other similar ones. That is why the accounts of ancient Initiates, which do not aim to be biographies in the usual sense, show such resemblance to the Gospel stories of Christ Jesus. And when we read the history of the greatest initiates, of Apollonius of Tyana, or indeed even of Buddha or Zarathustra, or the life of Osiris or of Orpheus, it often seems that important characteristics of their lives are the same as those narrated of Christ Jesus in the Gospels. But although we must grant that we have to seek in the Initiation ceremonies of the old Mysteries for the prototypes of important events narrated in the Gospels, on the other hand we see quite clearly that the great teachings of the life of Christ Jesus are saturated throughout with individual details which are not intended as a mere repetition of Initiation ceremonies, but make it very plain that what is described is actual fact. Must we not say that we receive a remarkably factual impression when the following is pictured for us in the Gospel of John XX:1–10:

Now on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene came to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb. So she ran, and went to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one whom Jesus loved, and said to them, ‘They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him.’ Peter then came out with the other disciple, and they went towards the tomb. They both ran, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first; and stooping to look in, he saw the linen cloths lying there, but he did not go in. Then Simon Peter came, following him, and he went into the tomb; he saw the linen cloths lying, and the napkins, which had been on his head, not lying with the linen cloths but rolled up in a place by itself. Then the other disciple, who reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed; for as yet they did not know the scripture, that he must rise from the dead. Then the disciples went back to their homes.

But Mary stood weeping outside the tomb, and as she wept she stooped to look into the tomb; and she saw two angels in white, sitting where the body of Jesus had lain, one at the head and one at the feet. They said to her, ‘Woman, why are you weeping?’ She said to them, ‘Because they have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him.’ Saying this, she turned and saw Jesus standing, but she did not know that it was Jesus.

Jesus said to her, ‘Woman, why are you weeping? Whom do you seek?’ Supposing him to be the gardener, she said to him, ‘Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him and I will take him away.’ Jesus said to her, ‘Mary.’ She turned and said to him in Hebrew,

‘Rabboni!’ (which means Teacher). Jesus said to her,

‘Do not hold me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father; but go to my brethren and say to them, I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.’

Here is a situation described in such detail that if we wish to picture it in imagination there is hardly anything lacking—when, for example, it is said that the one disciple runs faster than the other, or that the napkin which had covered the head was laid aside in another place, and so on. In every detail something is described which would have no meaning if it did not refer to a fact. Attention was drawn on a former occasion to one detail, that Mary did not recognise Christ Jesus, and we asked how was it possible that after three days anyone could fail to recognise in the same form a person previously known. Hence we had to note that Christ appeared to Mary in a changed form, or these words would have no meaning.

Here, therefore, a distinction must be kept in mind. First, we have to understand the Resurrection as a translation into historic fact of the awakening that took place in the holy Mysteries of all times, only with the difference that he who in the Mysteries raised up the individual pupil was the hierophant; while the Gospels indicate that He who raised up Christ is the Being whom we designate as the Father—that the Father Himself raised up the Christ. Here we are shown that what had formerly been carried out on a small scale in the depths of the Mysteries was now and once for all enacted for humanity by Divine Spirits, and that the Being who is designated as the Father acted as hierophant in the raising to life of Christ Jesus. Thus we have here, enhanced to the highest degree, something which formerly had taken place on a small scale in the Mysteries.

That is the first point. The other is that, interwoven with matters which carry us back to the Mysteries, there are descriptions so detailed that even today we can reconstruct from the Gospels the situations even to their minute particulars, as we have just seen in the passage read to you. But this passage includes one detail that calls for particular attention. There must be a meaning in the words, ‘For they did not as yet know the Scripture, that He must rise from the dead. Then the disciples went back to their homes.’ Let us ask: Of what had the disciples been able so far to convince themselves? It is described as clearly as anything can be that the linen wrappings are there, but the body is not there, is no longer in the grave. The disciples had not been able to convince themselves of anything else, and they understood nothing else when they now went home. Otherwise the words have no meaning. The more deeply you enter into the text, the more you must say that the disciples who were standing by the grave were convinced that the linen wrappings were there, but that the body was no longer in the grave. They went home with the thought: ‘Where has the body gone? Who has taken it out of the grave?’

And now, from the conviction that the body is not there, the Gospels lead us slowly to the events through which the disciples were finally convinced of the Resurrection. How were they convinced? Through the fact that, as the Gospels relate, Christ appeared to them by degrees, so that they could say, ‘He is there!’, and this went so far that Thomas, called the Doubter, could lay his finger in the prints of the wounds. In short, we can see from the Gospels that the disciples became convinced of the Resurrection through Christ having come to them after it as the Risen One. The proof for the disciples was that He was there. And if these disciples, who had gradually come to the conviction that Christ was alive, although He had died, had been asked what they actually believed, they would have said: ‘We have proofs that Christ lives.’ But they certainly would not have spoken as Paul spoke later, after he had gone through his experience on the road to Damascus.

Anyone who allows the Gospels and the Pauline Epistles to work upon him will notice the deep underlying difference between the fundamental tone of the Gospels as regards the understanding of the Resurrection, and the Pauline conception of it. Paul, indeed, draws a parallel between his conviction of the Resurrection and that of the Gospels, for in saying ‘Christ is risen’, he indicates that Christ, after He had been crucified, appeared as a living Being to Cephas, to the Twelve, then to five hundred brethren at one time; and last of all to himself, Paul, as to one born out of due time, Christ had appeared from out of the fiery glory of the Spiritual. Christ had appeared to the disciples also; Paul refers to that, and the events lived through with the Risen One were the same for Paul as they had been for the disciples. But what Paul immediately joins to these, as the outcome for him of the event of Damascus, is his wonderful and easily comprehensible theory of the Being of Christ.

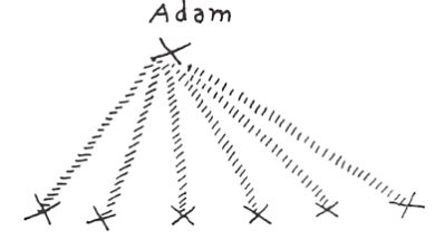

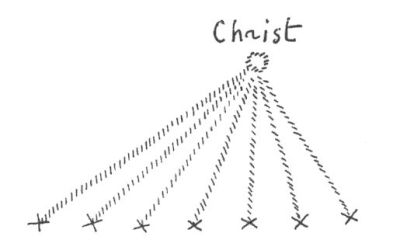

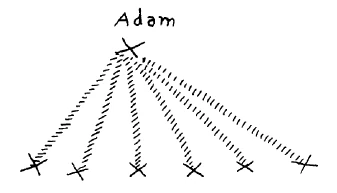

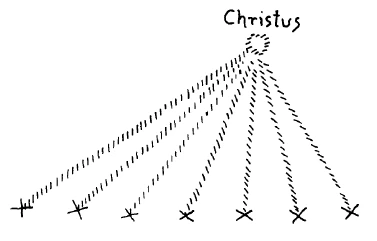

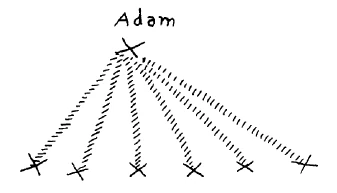

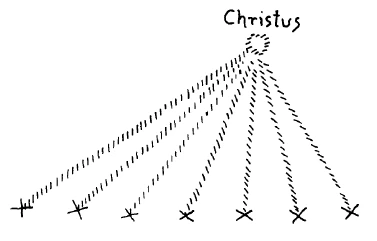

What, from the event of Damascus onwards, was the Being of Christ for Paul? The Being of Christ was for him the ‘Second Adam’; and he immediately differentiates between the first Adam and the second Adam, the Christ. He calls the first Adam the progenitor of men on Earth because he sees in him the first man, from whom all other men are descended. For Paul, it is Adam who has bequeathed to human beings the body which they carry about with them as a physical body. All men have inherited their physical body from Adam. This is the body which meets us in external Maya, and is mortal; it is the body inherited from Adam, the corruptible body, the physical body of man that decays in death. With this body men are ‘clothed’. The second Adam, Christ, is regarded by Paul as possessing, in contrast to the first, the incorruptible, the immortal body. Paul then affirms that through Christian evolution men are gradually made ready to put on the second Adam in place of the first Adam; the incorruptible body of the second Adam, Christ, in place of the corruptible body of the first Adam. What Paul seems to require of all who call themselves true Christians is something that violates all the old conceptions of the world. As the first corruptible body is descended from Adam, so must the incorruptible body originate from the second Adam, from Christ. Every Christian could say: ‘Because I am descended from Adam, I have a corruptible body as Adam had; but in that I set myself in the right relationship to Christ, I receive from Him, the second Adam, an incorruptible body.’ For Paul, this view shines out directly from the experience of Damascus. We can perhaps express what Paul wishes to say by means of a simple diagram:

Here we have (x, x ...) a number of people at a given time. Paul would trace them all back to the first Adam, from whom they are all descended and by whom they are given the corruptible body. According to Paul's conception, however, something else is possible. Just as human beings can say, ‘We are related because we are all descended from the one progenitor, Adam,’ so they can say, ‘As without any action of ours, through the relationships of human generation lines can be traced back to Adam, so it is possible for us to cause something else to arise within us; something that could make us different beings. Just as the natural lines lead back to Adam, so it must be possible to represent lines which lead, not to the corruptible body of the fleshly Adam, but to the body that is incorruptible. Through our relationship to Christ, we can—according to the Pauline view—bear this incorruptible body within us, just as through Adam we bear the Corruptible body.’

There is nothing more uncomfortable for the modern consciousness than this idea. For looking at the matter quite soberly, what does it demand from us? It demands something which, for modern thought, is really monstrous. Modern thought has long disputed whether all human beings are descended from one primeval human being, but it may be allowed that all are descended from a single human being who was the first on earth as regards physical consciousness. Paul, however, demands the following. He says: ‘If you desire to be a Christian in the true sense, you must conceive that within you something can arise which can live in you, and from which you can draw spiritual lines to a second Adam, to Christ, to that very Christ who on the third day rose from the grave, just as all men can trace lines back to the physical body of the first Adam.’ So Paul demands that all who call themselves Christians should cause something within them to arise; something leading to that entity which on the third day rose out of the grave in which the body of Christ Jesus had been laid. Anyone who does not grant this cannot come into any relationship with Paul; he cannot say he understands Paul. If man, as regards his corruptible body, is descended from the first Adam, then, by receiving the Being of Christ into his own being, he has the possibility of having a second ancestor. This ancestor, however, is He who, on the third day after His body had been laid in the earth, rose out of the grave.

Let us clearly understand that Paul makes this demand, however displeasing it may be to modern thinkers. From this Pauline statement we will indeed approach the modern thinker; but one ought not to have any other opinion concerning that which meets us so clearly in the Pauline writings; one ought not to twist the meaning of something so clearly expressed by Paul. Certainly it is pleasant to interpret something allegorically and to say it was meant in such and such a way; but all these interpretations make no sense. If we wish to connect a meaning with the Pauline statement we are bound to say—even if modern consciousness regards it as superstition—that, according to Paul, Christ rose from the dead after three days.

Let us go further. An assertion such as this, made by Paul after he had reached the summit of his initiation through the event of Damascus—the assertion concerning the second Adam and His rising from the grave—could be made only by someone whose whole mode of thought and outlook had been derived from Greek thought; by one whose roots were in Greece, even if he were also a Hebrew; by one who in a certain respect had brought all his Hebraism as an offering to the Greek mind. For, if we come closer to all this, what is it that Paul really declares? Looking with inner vision on that which the Greeks loved and valued, the external form of the human body, concerning which they had the tragic feeling that it comes to an end when the individual passes through the gate of death, Paul says: ‘With the Resurrection of Christ, the body has been raised in triumph from the grave.’ If we are to build a bridge between these two world-outlooks, we can best do it in the following way.

The Greek hero said from his Greek feeling: ‘Better a beggar in the upper world than a king in the land of shades.’ He said this because he was convinced that the external form of the physical body, so highly cherished by the Greeks, was lost for ever in passing through the gate of death. On this same soil, out of which this tragic mood of intoxication with beauty had grown, Paul appeared, he who first proclaimed the Gospel to the Greeks. We do not deviate from his words if we translate them as follows: ‘That which you value above all, the human bodily form, will no longer be destroyed. Christ is risen as the first of those who are raised from the dead! The Form of the physical body is not lost, but is given back to humanity through the Resurrection of Christ!’ That which the Greeks valued most highly was given back to them with the Resurrection by Paul the Jew, who had been steeped in Greek culture. Only a Greek would so think and speak, but only someone who had become a Greek with all the preconceptions derived from his Jewish ancestry. Only a Jew who had become a Greek could speak in this way; no one else.

But how can we approach these things from the standpoint of Spiritual Science? For we have reached the point of knowing that Paul demands something which thoroughly upsets the calculations of the modern thinker. Let us endeavour from the standpoint of Spiritual Science to get nearer to what Paul demands. Let us collect what we know from Spiritual Science, so as to bring an idea to meet Paul's statement.

When we review the very simplest spiritual-scientific truths, we know that man consists of physical body, etheric body, astral body, and Ego. If now you ask someone who has studied Spiritual Science a little, but not very thoroughly, whether he knows the physical body of man, he will be sure to answer: ‘I know it quite well, for I see it when a person stands before me. The other members are supersensible, invisible, and one cannot see them, but the physical human body I know very well.’ Is it really the physical body of man that appears before our eyes when we meet a man with our ordinary vision? I ask you, who without clairvoyant vision has ever seen a physical human body? What is it that people have before them if they see only with physical eyes and physical understanding? A human body, but one consisting of physical body, etheric body, astral body, and Ego. And when a man stands before us, it is as an organised assembly of physical body, etheric body, astral body, and Ego. It would make as little sense to say that a physical body stood before us as it would if, when giving someone a glass of water, we were to say, ‘There is hydrogen in that glass.’ Water consists of hydrogen and oxygen, as man consists of physical, etheric and astral bodies, and Ego. Their assemblage is visible, just as water is, but the hydrogen and oxygen are not. Anyone who said he saw hydrogen in the water would be obviously mistaken. So is anyone who thinks he sees the physical body when he sees a man in the external world. What he normally sees is not a physical human body, but a four-membered being. He sees the physical body only in so far as it is permeated by the other members of the human being. And it is then changed in the same way that hydrogen is changed when it is permeated with oxygen in water. For hydrogen is a gas, and oxygen also; from the two gases united we get a liquid. Why should it be incomprehensible that the man who meets us in the physical world is quite unlike his single members, the physical, etheric and astral bodies and the Ego, just as water is quite unlike hydrogen? And so he is! Hence we cannot rely upon the Maya which appears to us as the physical body. We must think of the physical body in a quite different way if we want to draw nearer to its nature.

The observation of the physical human body, in itself, belongs to the most difficult clairvoyant problems, the hardest of all! Suppose we allow the external world to perform on man the experiment which is similar to the disintegration of water into hydrogen and oxygen. In death this experiment is performed by the great world. We then see how man lays aside his physical body. But does he really lay aside his physical body? The question seems absurd, for what could be clearer than the apparent fact that at death man lays aside his physical body? But what is it that he lays aside? It is something no longer imbued with the physical body's most important possession during life: its Form. Directly after death the Form begins to withdraw from the dead body. We are left with decaying substances, no longer characterised by the Form. The body laid aside is composed of substances and elements which we can trace also in Nature; in the natural order of things they would not produce a human Form. Yet this Form belongs quite essentially to the physical human body. To ordinary clairvoyance it seems evident that at death a person simply discards these material substances, which are then handed over to decay or burning, and that nothing of the physical body is left. The clairvoyant then observes how after death the Ego, astral body, and etheric body remain connected during the person's review of his past life. Then he sees how the etheric body separates itself, how an extract of it remains, while the main portion dissolves in one way or another into the general cosmic ether. It does indeed seem that the person has laid aside his physical body, with its substances and forces, and then, after a few days, the etheric body. When the clairvoyant follows the person further through the Kamaloka period, he sees how an extract of the astral body goes with him during the life between death and a new birth, while the rest of the astral body is given over to the cosmic astrality.

So we see that physical, etheric and astral bodies are laid aside, and that the physical body seems to drain away completely into materials and forces which, through decay or burning or some other form of dissolution, are returned to the elements. But the more clairvoyance is developed in our time, the clearer will it be that the physical forces and substances laid aside are not the whole physical body, for its complete configuration could never derive from them alone. To these substances and forces there belongs something else, best called the ‘Phantom’ of the man. This Phantom is the Form-shape which as a spiritual texture works up the physical substances and forces so that they fill out the Form which we encounter as the man on the physical plane. The sculptor can bring no statue into existence if he merely takes marble or something else, and strikes away wildly so that single pieces spring off just as the substance permits. As the sculptor must have the ‘thought’ which he impresses on the substance, so is a ‘thought’ related to the human body: not in the same way as the thought of the artist, for the material of the human body is not marble or plaster, but as a real thought, the Phantom, in the external world. Just as the thought of the plastic artist is stamped upon his material, so the Phantom of the physical body is stamped upon the substances of the earth which we see given over after death to the grave or the fire. The Phantom belongs to the physical body as its enduring part, a more important part than the external substances. The external substances are merely loaded into the network of the human Form, as one might load apples into a cart. You can see how important the Phantom is. The substances which fall asunder after death are essentially those we meet externally in nature. They are merely caught up by the human Form.

If you think more deeply, can you believe that all the work of the great Divine Spirits though the Saturn, Sun, and Moon periods has merely created something which is handed over at death to the elements of the Earth? No—that which was developed during the Saturn, Sun, and Moon periods is not the physical body that is laid aside at death. It is the Phantom, the Form, of the physical body. We must be quite clear that to understand the physical body is not an easy thing. Above all, this understanding must not be sought for in the world of illusion, the world of Maya. We know that the foundation, the germ, of this Phantom of the physical body was laid down by the Thrones during the Saturn period; during the Sun period the Spirits of Wisdom worked further upon it, the Spirits of Movement during the Moon period, and the Spirits of Form during the Earth period. And it is only in this period that the physical body received the Phantom. We call these Spirits the Spirits of Form, because they really live in the Phantom of the physical body. So in order to understand the physical body, we must go back to the Phantom.

If we look back to the beginning of our Earth-existence, we can say that the hosts from the ranks of the higher Hierarchies who had prepared the physical human body in its own proper Form during the Saturn, Sun and Moon periods, up to the Earth period, had from the outset placed this Phantom within the Earth evolution. In fact the Phantom, which cannot be seen with the physical eye, was what was first there of the physical body of man. It is a transparent body of force. What the physical eye sees are the physical substances which a person eats and takes into himself, and they fill out the invisible Phantom. If the physical eye looks upon a physical body, what it sees is the mineral part that fills the physical body, not the physical body itself. But how has this mineral part found its way into the Phantom of man's physical body? To answer this question, let us picture once more the genesis, the first ‘becoming’, of man on Earth.

From Saturn, Sun and Moon there came over that network of forces which in its true form meets us as the invisible Phantom of the physical body. For a higher clairvoyance it appears as Phantom only when we look away from all the external substance that fills it out. This is the Phantom which stands at the starting-point of man's Earth existence, when he was invisible as a physical body. Let us suppose that to this Phantom of the physical body the etheric body is added; will the Phantom then become visible? Certainly not; for the etheric body is invisible for ordinary sight. Thus the physical body as Phantom, plus etheric body, is still invisible to external physical sense. And the astral body even more so; hence the combination of physical body as Phantom with the etheric and astral bodies is still invisible. And when the Ego is added it would certainly become perceptible inwardly, but not externally visible. Thus, as man came over out of the Saturn, Sun, and Moon periods, he was still visible only to a clairvoyant. How did he become visible? But for the occurrence described in the Bible symbolically, and factually in occult science, as the entry of the Lucifer influence, he would not have become visible. What happened through that influence?

Read what is said in Occult Science. Out of that path of evolution in which his physical, etheric and astral bodies were still invisible, man was thrown down into denser matter, and was compelled under the influence of Lucifer to take this denser matter into himself. If the Lucifer force had not been introduced into our astral body and Ego, this dense materiality would not have become as visible as it has become. Hence we have to represent man as an invisible being, made visible in matter only through forces which entered into him under the influence of Lucifer. Through this influence external substances and forces are drawn into the domain of the Phantom and permeate it. As when we pour a coloured fluid into a transparent glass, so that the glass looks coloured, so we can imagine that the Lucifer influence poured forces into the human Phantom, with the result that man was adapted for taking in on Earth the requisite substances and forces which make his Form visible. Otherwise his physical body would have remained always invisible.

The alchemists always insisted that the human body really consists of the same substance that constitutes the perfectly transparent, crystal-clear ‘Philosopher's Stone’. The physical body is itself entirely transparent, and it is the Lucifer forces in man which have brought him to a non-transparent state and placed him before us so that he is opaque and tangible. Hence you will understand that man has become a being who takes up external substances and forces of the Earth, which are given off again at death, only because Lucifer tempted him, and certain forces were poured into his astral body. It follows that because the Ego entered into connection with the physical, etheric and astral bodies under the influence of Lucifer, man became what he is on earth and otherwise would not have been—the bearer of a visible, earthly organism.

Now let us suppose that at a certain point of time in life the Ego were to go out from a human organism, so that there stood before us physical, etheric and astral bodies, but not the Ego. This is what happened in the case of Jesus of Nazareth in the thirtieth year of His life. The human Ego then left this cohesion of physical, etheric and astral bodies. And into this cohesion the Christ-Being entered at the Baptism in Jordan. We now have the physical, etheric and astral bodies of a man, and the Christ-Being. The Christ-Being had now taken up His abode in a human organism, as otherwise the Ego would have done. What now differentiates this Christ Jesus from all other men on Earth? It is this: that all other men bear within them an Ego that once was overcome by Lucifer's temptation, but Jesus no longer bears an Ego within Him; instead, He bears the Christ-Being. So that from this time, beginning with the Baptism in Jordan, Jesus bears within Himself the residual effects that had come from Lucifer, but with no human Ego to allow any further Luciferic influences to enter his body. A physical body, an etheric body, and astral body—in which the residue of the earlier Luciferic influences was present, but into which no more Luciferic influence could enter—and the Christ-Being: thus was Christ Jesus constituted.

Let us set before us exactly what the Christ is from the Baptism in Jordan until the Mystery of Golgotha: a physical body, an etheric body, and an astral body which makes this physical body together with the etheric body visible because it still contains the residue of the Luciferic influence. Because the Christ-Being had the astral body that Jesus of Nazareth had had from birth to his thirtieth year, the physical body was visible as the bearer of the Christ. Thus from the time of the Baptism in Jordan we have before us a physical body which as such would not be visible on the physical plane; an etheric body which as such would not have been perceptible; the astral body which makes the other two bodies visible and so makes the body of Jesus of Nazareth into a visible body; and, within this organism, the Christ-Being.

We will inscribe firmly in our souls this four-fold nature of Christ Jesus, saying to ourselves: Every person who stands before us on the physical plane consists of physical body, etheric body, astral body, and Ego; and this Ego is such that it always works into the astral body up to the hour of death. The Christ-Jesus-Being, however, stands before us as One who had physical body, etheric body and astral body, but no human Ego, so that during the three years up to his death he was not subject to the influences that normally work upon human beings. The only influence came from the Christ-Being.

Sechster Vortrag

Von denjenigen Dingen, die gestern besprochen worden sind, ausgehend, werden wir uns den bedeutsamsten Kernfragen des Christentums nähern können und in das eigentliche Wesen des Christentums einzudringen versuchen. Wir werden sehen, wie wir eigentlich nur auf diesem Wege durchschauen können, was der Christus-Impuls für die Menschheitsentwickelung geworden ist, und was er in Zukunft werden soll.

Wenn die Menschen immer wieder und wieder betonen, daß die Antworten auf die höchsten Fragen nicht so kompliziert sein sollen, sondern daß die Wahrheit im Grunde genommen in einfachster Art an jeden Menschen unmittelbar herangebracht werden müsse, und wenn bei einer solchen Gelegenheit gesagt wird, daß zum Beispiel der Apostel Johannes in seinem höchsten Alter den Extrakt des Christentums in die Wahrheitsworte zusammengefaßt habe: Kinder, liebet euch!, so darf daraus niemand den Schluß ziehen: Ich kenne das Wesen des Christentums, kenne das Wesen aller Wahrheit für die Menschen, indem ich einfach die Worte ausspreche: Kinder, liebet euch! Denn daß der Apostel Johannes diese Worte einfach aussprechen durfte, dazu hatte er sich mehrere Vorbedingungen erworben. Erstens wissen wir, daß er am Ende eines langen Lebens im fünfundneunzigsten Lebensjahre eigentlich erst zu einem solchen Ausspruche übergegangen ist, daß er sich also in seiner damaligen Inkarnation erst das Recht erworben hatte, solches Wort auszusprechen; so daß er damit wohl als ein Zeuge dasteht, daß dieses Wort, von jedem beliebigen Menschen ausgesprochen, nicht dieselbe Kraft habe wie bei dem Apostel Johannes. Aber noch etwas anderes hat er sich errungen. Er ist — wenn es auch die Kritik bestreitet — der Verfasser des Johannes-Evangeliums, der Apokalypse und der Briefe des Johannes. Er hat also nicht immer sein Leben lang gesagt: Kinder, liebet euch!, sondern er hat zum Beispiel ein Werk geschrieben, das zu den schwersten Werken der Menschheit gehört: die Apokalypse — und ein Werk, das zu den intimsten und am tiefsten in die menschliche Seele eindringenden Werken gehört: das JohannesEvangelium. Er hat sich das Recht, solche Worte zu sagen, erst durch ein langes Leben und durch das, was er geleistet hat, erworben. Und wenn ihm jemand dieses Leben nachlebt und tut, was er getan hat, und dann ihm nachspricht: Kinder, liebet euch!, dann kann man im Grunde genommen gegen ein solches Vorgehen nichts einwenden. Aber wir müssen uns darüber klar sein, daß Dinge, die in wenig Worte zusammengefaßt werden können, dadurch, daß wir sie mit so wenigen Worten ausdrücken, ja recht viel bedeuten können, daß sie aber auch nichtssagend sein können. Und gar mancher, der ein Weisheitswort, das vielleicht bei gehörigen Voraussetzungen etwas sehr Tiefes bedeutet, nur so ausspricht und damit unendlich viel gesagt zu haben glaubt, erinnert an eine Erzählung von einem Herrscher, der einmal ein Gefängnis besuchte und dem ein Bewohner dieses Gefängnisses, ein Dieb, vorgeführt wurde. Da richtete der Herrscher an den Dieb die Frage, warum er denn gestohlen habe, und der Dieb sagte, weil er hungrig gewesen sei. Nun, die Frage, wie dem Hunger abzuhelfen sei, ist eine Frage, mit der sich schon viele Menschen beschäftigt haben. Der betreffende Herrscher aber meinte zu dem Dieb, er habe noch nie gehört, daß man stehle, wenn man hungrig ist, sondern daß man esse! Zweifellos ist das eine richtige Antwort, daß man esse und nicht stehle, wenn man hungrig ist. Aber es handelt sich darum, ob die betreffende Antwort auch in die entsprechende Situation hineinpaßt. Denn damit, daß die Antwort wahr ist, ist noch nicht gesagt, daß sie auch etwas aussprechen kann, was eine Bedeutung oder einen Wert hat zur Entscheidung der entsprechenden Angelegenheit. So kann auch aus dem Munde des Schreibers der Apokalypse und des Johannes-Evangeliums im höchsten Alter das Wort: Kinder, liebet euch! als aus dem Wesen des Christentums heraus gesprochen sein — dasselbe Wort, das aus dem Munde eines andern eine bloße Phrase sein kann. Deshalb müssen wir uns schon einmal damit bekanntmachen, daß wir die Dinge zum Verständnis des Christentums weit herholen müssen, gerade damit wir sie dann auf die einfachsten Wahrheiten des alltäglichen Lebens anwenden können. Wir mußten gestern an die für das moderne Denken verhängnisvolle Frage gehen, wie es mit dem steht, was wir in der viergliedrigen Wesenheit des Menschen den physischen Leib nennen. Wir werden sehen, wie das, was gestern berührt worden ist im Hinblick auf die dreifache Anschauung des Griechentums, des Judentums und des Buddhismus, uns weiterführen wird zum Verständnis des Wesens des Christentums. Zunächst aber werden wir hingelenkt auf eine Frage, die tatsächlich im Mittelpunkte der ganzen christlichen Weltanschauung steht, wenn wir uns über die Frage nach dem Schicksal des physischen Leibes unterrichten; denn wir werden damit zu nichts Geringerem hingeführt als zu jener Wesenskernfrage des Christentums: Wie steht es mit der Auferstehung Christi? Dürfen wir annehmen, daß es wichtig ist für das Verständnis des Christentums, ein Verständnis zu haben über die Auferstehungsfrage?

Daß dies wichtig ist, dazu brauchen wir uns nur dessen zu erinnern, was im ersten Korintherbriefe des Paulus steht (Kapitel 15, 14-20):

«Wenn aber Christus nicht auferweckt worden ist, so ist unsere Predigt nichtig, nichtig aber auch euer Glaube. Dann würden wir aber auch erfunden als falsche Zeugen Gottes, weil wir wider Gott zeugten, daß er Christus auferweckt hätte, während er ihn doch nicht auferweckt hat, wenn wirklich keine Toten auferstehen. Denn werden keine Toten auferweckt, so ist auch Christus nicht auferweckt. Ist aber Christus nicht auferweckt, so ist euer Glaube eitel, so seid ihr noch in euren Sünden; dann sind auch verloren, die in Christus entschlafen sind. Wenn wir nur solche sind, die in diesem Leben nichts als ihre Hoffnung auf Christus haben, so sind wir die beklagenswertesten aller Menschen. Nun aber ist Christus auf erweckt von den Toten als der Erstling der Entschlafenen.»

Wir müssen dabei darauf hinweisen, daß das Christentum, wie es sich über die Welt verbreitet hat, zunächst von Paulus ausgegangen ist. Und wenn wir uns einen Sinn dafür angeeignet haben, die Worte ernst zu nehmen, so dürfen wir nicht an den wichtigsten Worten des Paulus einfach vorübergehen und etwa sagen: Wir lassen die Frage der Auferstehung ungeklärt. Denn was ist es, was Paulus sagt? Daß überhaupt das ganze Christentum keine Berechtigung und der ganze Christenglaube keinen Sinn habe, wenn die Auferstehung keine Tatsache sei! Das sagt Paulus, von dem das Christentum als historische Tatsache seinen Ausgangspunkt genommen hat. Und damit ist im Grunde genommen nichts Geringeres gesagt als: Wer die Auferstehung aufgeben will, muß aufgeben das Christentum im Sinne des Paulus.

Und jetzt wenden wir unseren Blick über fast zwei Jahrtausende und fragen einmal an bei den Menschen der Gegenwart, wie sie sich nach den Vorbedingungen der gegenwärtigen Zeitbildung zu der Auferstehungsfrage verhalten müssen. Ich will jetzt noch nicht auf diejenigen Rücksicht nehmen, die etwa den ganzen Jesus wegleugnen; dann ist es natürlich außerordentlich leicht, sich über die Auferstehungsfrage klar zu werden; und sie ist im Grunde genommen am leichtesten damit zu beantworten, daß man sagt: Jesus hat überhaupt nicht gelebt, also braucht man sich nicht über die Auferstehungsfrage die Köpfe zu zerbrechen. Wenn wir also von solchen Leuten absehen, so wollen wir uns einmal an diejenigen Menschen wenden, die zum Beispiel um die Mitte oder im letzten Drittel des letzten Jahrhunderts übergegangen sind zu den gebräuchlichen Vorstellungen unserer Zeit, in denen wir ja noch selber stecken; und bei ihnen wollen wir einmal Anfrage halten, wie sie vermöge ihrer ganzen Zeitbildung über die Auferstehungsfrage denken müssen. Wenn wir uns da an einen Mann wenden, der großen Einfluß gewonnen hat auf die Denkweise derjenigen, die sich für die aufgeklärtesten Menschen halten, an David Friedrich Strauß, so lesen wir bei ihm in seiner Schrift über den Denker Reimarus des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts folgendes: «Die Auferstehung Jesu ist recht ein Schibboleth, an dem sich nicht nur die verschiedenen Auffassungen des Christentums, sondern verschiedene Weltanschauungen und geistige Entwickelungsstufen voneinander scheiden.» Und fast zur selben Zeit lesen wir in einer schweizerischen Zeitschrift die Worte: «Sobald ich mich von der Wirklichkeit der Auferstehung Christi, dieses absoluten Wunders, überzeugen kann, zerreiße ich die moderne Weltanschauung. Dieser Riß durch die, wie ich glaube, unverbrüchliche Naturordnung wäre ein unheilbarer Riß durch mein System, durch meine ganze Gedankenwelt.»

Fragen wir uns, wie viele Menschen unserer Gegenwart, die nach den gegenwärtigen Standpunkten diese Worte unterschreiben müssen und auch unterschreiben werden, sagen werden: Wenn ich genötigt sein sollte, die Auferstehung als eine historische Tatsache anzuerkennen, so zerreiße ich mein ganzes philosophisches oder sonstiges System. Fragen wir: Wie sollte auch in die Weltanschauung des modernen Menschen die Auferstehung als eine historische Tatsache hineinpassen?

Erinnern wir uns daran, daß wir schon in dem ersten öffentlichen Vortrage darauf hingedeutet haben, wie in erster Linie die Evangelien genommen sein wollen: nämlich als Einweihungsschriften. Was als die größten Tatsachen in den Evangelien geschildert ist, sind im Grunde genommen Einweihungstatsachen, Vorgänge, welche sich zunächst im Innern des Tempelgeheimnisses der Mysterien abgespielt haben, wenn dieser oder jener Mensch, der dafür würdig erachtet worden war, durch die Hierophanten eingeweiht wurde. Da hat ein solcher Mensch, nachdem er lange Zeit hindurch dazu vorbereitet worden war, eine Art Tod und eine Art Auferstehung durchgemacht; und auch gewisse Lebensverhältnisse mußte er durchmachen, welche uns in den Evangelien wiedererscheinen — zum Beispiel als die Versuchungsgeschichte, als die Geschichte auf dem Ölberg und dergleichen. Weil sich das so verhält, erscheinen auch die Beschreibungen der alten Eingeweihten, die nicht Biographien im gewöhnlichen Sinne des Wortes sein wollen, so ähnlich den Evangeliengeschichten von dem Christus Jesus. Und wenn wir die Geschichte des Apollonius von Tyana, ja selbst die Buddha-Geschichte oder die Zarathustra-Geschichte lesen, das Leben des Osiris, des Orpheus, wenn wir gerade das Leben der größten Eingeweihten lesen, dann ist es oft, als wenn uns dieselben wichtigen Lebenszüge da entgegentreten, wie sie in den Evangelien geschildert werden vom Christus Jesus. Aber wenn wir auch zugeben müssen, daß wir auf diese Art für wichtige Vorgänge, die uns in den Evangelien dargestellt werden, die Vorbilder zu suchen haben in den Einweihungszeremonien der alten Mysterien, so sehen wir doch auf der anderen Seite handgreiflich, daß die großen Lehren des ChristusJesus-Lebens überall durchtränkt sind in den Evangelien mit Einzelangaben, die nun nicht eine bloße Wiederholung der Einweihungszeremonien sein wollen, sondern die uns recht sehr darauf hinweisen, daß unmittelbar Tatsächliches geschildert wird. Oder müssen wir nicht sagen, daß es in einer merkwürdigen Weise einen tatsächlichen Eindruck macht, wenn uns im Johannes-Evangelium folgendes geschildert wird (Kapitel 20, 1-17):

«Am ersten Wochentage aber kommt Maria, die von Magdala, morgens frühe, da es noch dunkel war, zu dem Grabe, und sieht den Stein vom Grabe weggenommen. Da läuft sie und geht zu Simon Petrus und zu dem anderen Jünger, welchen Jesus lieb hatte, und sagt zu ihnen: Sie haben den Herrn aus dem Grabe genommen, und wir wissen nicht, wo sie ihn hingelegt haben. Da ging Petrus hinaus und der andere Jünger, und gingen zum Grabe. Es liefen aber die beiden miteinander und der andere Jünger lief voraus, schneller als Petrus, und kam zuerst an das Grab, und beugte sich vor und sieht die Leintücher da liegen, hinein ging er jedoch nicht. Da kommt Simon Petrus hinter ihm drein, und er trat in das Grab hinein und sieht die Leintücher liegen, und das Schweißtuch, das auf seinem Kopf gelegen war, nicht bei den Leintüchern liegen, sondern für sich zusammengewickelt an einem besonderen Ort. Hierauf ging denn auch der andere Jünger hinein, der zuerst zum Grab gekommen war, und sah es und glaubte. Denn noch hatten sie die Schrift nicht verstanden, daß er von den Toten auferstehen müsse. Da gingen die Jünger wieder heim. Maria aber stand außen am Grabe weinend. Indem sie so weinte, beugte sie sich vor in das Grab, und schaut zwei Engel in weißen Gewändern da sitzend, einen zu Häupten und einen zu Füßen, wo der Leichnam Jesu gelegen war. Dieselben sagen zu ihr: Weib, was weinst du? Sagt sie zu ihnen: weil sie meinen Herrn weggenommen, und ich weiß nicht, wo sie ihn hingelegt haben. Als sie dies gesagt hatte, kehrte sie sich um und schaut Jesus dastehend, und erkannte ihn nicht. Sagt Jesus zu ihr: Weib, was weinst du? Wen suchst du? Sie, in der Meinung, es sei der Gartenhüter, sagt zu ihm: Herr, wenn du ihn fortgetragen, sage mir, wo du ihn hingelegt, so werde ich ihn holen. Sagt Jesus zu ihr: Maria! Da wendet sie sich und sagt zu ihm hebräisch: Rabbuni! das heißt: Meister. Sagt Jesus zu ihr: Rühre mich nicht an; denn noch bin ich nicht aufgestiegen zu dem Vater!»

Da haben wir eine Situation so mit Einzelheiten geschildert, daß wir kaum etwas vermissen, wenn wir uns in unserer Imagination ein Bild machen wollen, so, wenn zum Beispiel gesagt wird, daß der eine Jünger schneller läuft als der andere, daß das Schweißtuch, das den Kopf bedeckt hatte, fortgelegt ist an eine andere Stelle und so weiter. In allen Einzelheiten sehen wir etwas geschildert, was keinen Sinn hätte, wenn es sich nicht auf Tatsachen beziehen würde. Auf eins wurde auch schon bei anderer Gelegenheit aufmerksam gemacht, daß uns erzählt wird: Maria erkannte den Christus Jesus nicht. Und es wurde darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie es möglich wäre, daß man jemanden, den man vorher gekannt hat, nach drei Tagen nicht in derselben Gestalt wiedererkennen würde? Daß der Christus also in einer veränderten Gestalt der Maria erschienen ist, das muß auch berücksichtigt werden; denn sonst hätten diese Worte auch keinen Sinn.

Zweierlei können wir daher sagen: Die Auferstehung müssen wir tatsächlich auffassen als das Historischwerden der Auferweckung in den heiligen Mysterien zu allen Zeiten — nur mit dem Unterschiede, daß wir sagen müssen: Der, welcher die einzelnen Mysterienschüler auferweckt hat, war in den Mysterien der Hierophant; in den Evangelien wird aber darauf hingewiesen, wie der, der den Christus auferweckt hat, die Wesenheit ist, die wir mit dem Vater bezeichnen, daß der Vater selber den Christus auferweckt hat. Wir werden damit auch darauf hingewiesen, daß das, was sich sonst in einem kleineren Maßstabe in den Tiefen der Mysterien zugetragen hat, von den göttlichen Geistern hingestellt worden ist für die Menschheit einmal auf Golgatha, und daß die Wesenheit, die als der Vater bezeichnet wird, selber als Hierophant aufgetreten ist zur Erweckung des Christus Jesus. So haben wir also ins höchste gesteigert, was sonst im kleineren in den Mysterien aufgetreten ist. Das ist das eine. Das andere ist, daß mit den Dingen, die auf die Mysterien zurückführen, verwoben sind Beschreibungen von solchen Einzelheiten, daß wir uns die Situationen auch heute noch an den Evangelien bis in die Einzelheiten — wie wir an dem angeführten Bilde gesehen haben — rekonstruieren können. Eins ist es, was als noch wichtiger in Betracht kommt. Jene Worte müssen einen Sinn haben: «Denn noch hatten sie die Schrift nicht verstanden, daß er von den Toten auferstehen müsse. Da gingen die Jünger wieder heim.» Fragen wir also: Wovon hatten sich bis dahin die Jünger überzeugen können? So klar, wie nur irgend etwas klar sein kann, wird uns geschildert, daß die Leintücher da sind, daß der Leichnam nicht da ist; nicht mehr im Grabe ist. Von nichts anderem hatten sich die Jünger überzeugen können, und nichts anderes verstanden sie, als sie jetzt wieder heim gingen. Sonst hätten die Worte keinen Sinn. Je tiefer Sie eindringen in den Text, desto mehr müssen Sie sich sagen: Die Jünger, die am Grabe standen, überzeugten sich davon, daß die Leintücher da waren, daß aber der Leichnam nicht mehr im Grabe war; und sie gingen heim mit dem Gedanken: wo ist nun der Leichnam hin? Wer hat ihn aus dem Grabe gebracht?

Und jetzt führen uns von der Überzeugung, daß der Leichnam nicht da ist, die Evangelien langsam zu den Dingen, durch welche die Jünger eigentlich von der Auferstehung überzeugt werden. Wodurch werden sie überzeugt? Dadurch, daß, wie die Evangelien erzählen, ihnen nach und nach der Christus erschienen ist, daß sie sich sagen konnten: Er ist da! was sogar so weit ging, daß Thomas, der der Ungläubige genannt wird, seine Finger in die Wundmale legen konnte. Kurz, aus den Evangelien können wir sehen, daß sich die Jünger von der Auferstehung erst dadurch haben überzeugen lassen, daß ihnen der Christus nachher als Auferstandener entgegengetreten ist. Daß er da war, das war für die Jünger der Beweis. Und hätte man diese Jünger, so wie sie sich nach und nach die Überzeugung verschafft hatten, daß der Christus lebt, trotzdem er gestorben war, — hätte man sie gefragt um den eigentlichen Inhalt ihres Glaubens, so würden sie gesagt haben: Wir haben die Beweise, daß der Christus lebt! Aber sie würden durchaus nicht so gesprochen haben, wie später Paulus gesprochen hat, als er das Ereignis von Damaskus erlebt hatte.

Wer das Evangelium und die Paulus-Briefe auf sich wirken läßt, wird merken, welch tiefgehender Unterschied in bezug auf die Auffassung der Auferstehung zwischen dem Grundton der Evangelien und der paulinischen Auffassung ist. Zwar parallelisiert Paulus seine Auferstehungsüberzeugung mit der der Evangelien; denn indem er sagt, Christus sei erstanden, weist er darauf hin, daß der Christus als ein Lebendiger, nachdem er gekreuzigt worden war, dem Kephas, den Zwölfen, dann fünfhundert Brüdern auf einmal und zuletzt ihm auch, als einer unzeitigen Geburt, erschienen ist aus dem Feuerschein des Geistigen. So ist er auch den Jüngern erschienen; darauf weist Paulus hin. Und die Erlebnisse mit dem Auferstandenen waren für Paulus keine anderen als für die Jünger. Was er aber gleich daran anknüpfl, was für ihn das Ereignis von Damaskus ist, das ist seine wunderbare und leicht zu begreifende Theorie von der Wesenheit des Christus. Denn was wird vom Ereignis von Damaskus an für ihn die Wesenheit des Christus? Sie wird für ihn der zweite Adam. Und Paulus unterscheidet sogleich den ersten Adam und den zweiten Adam: den Christus. Den ersten Adam nennt er den Stammvater der Menschen auf der Erde. Aber in welcher Weise? Wir brauchen nicht weit zu gehen, um uns die Antwort auf diese Frage zu verschaffen. Er nennt ihn den Stammvater der Menschen auf Erden, indem er in ihm den ersten Menschen sieht, von dem alle übrigen Menschen abstammen — das heißt für Paulus: derjenige, der den Menschen vererbt hat den Leib, den sie als einen physischen an sich tragen. So hatten alle Menschen von Adam ihren physischen Leib vererbt. Das ist der Leib, der uns zunächst in der äußeren Maja entgegentritt, und der sterblich ist; es ist der von Adam vererbte, verwesliche Leib, der dem Tode verfallende physische Leib des Menschen. Mit diesem Leib — wir können den Ausdruck, denn er ist nicht schlecht, geradezu gebrauchen — sind die Menschen «angezogen». Und den zweiten Adam, den Christus, betrachtet Paulus im Gegensatz dazu als innehabend den unverweslichen, den unsterblichen Leib. Und durch die christliche Entwickelung setzt Paulus voraus, daß die Menschen allmählich in die Lage kommen, an die Stelle des ersten Adam den zweiten Adam zu setzen, an die Stelle des verweslichen Leibes des ersten Adam den unverweslichen Leib des zweiten Adam, des Christus, anzuziehen. Nichts Geringeres also, als was alle alte Weltanschauung zu durchlöchern scheint, nichts Geringeres scheint Paulus von denen zu fordern, die sich echte Christen nennen. Wie der erste, verwesliche Leib abstammt von Adam, so muß von dem zweiten Adam, von Christus, stammen der unverwesliche Leib. So daß jeder Christ sich sagen müßte, weil ich von Adam abstamme, habe ich einen verweslichen Leib, wie ihn Adam hatte; und indem ich mich in das rechte Verhältnis zu dem Christus setze, bekomme ich von Christus — dem zweiten Adam — einen unverweslichen Leib. Diese Anschauung leuchtet für Paulus unmittelbar hervor aus dem Damaskus-Ereignis. Mit anderen Worten: was will Paulus sagen? Wir kön nen es vielleicht mit einer einfachen schematischen Zeichnung ausdrücken.

Wenn wir eine Anzahl von Menschen zu einer bestimmten Zeit haben (X), so wird Paulus alle stammbaumgemäß zurückführen zu dem ersten Adam, von dem sie alle abstammen, und der ihnen den verweslichen Leib gegeben hat. Ebenso muß nach der Vorstellung des Paulus ein anderes möglich sein. Wie die Menschen in bezug auf ihre Menschlichkeit sich sagen können: wir sind verwandt, weil wir von dem einen Urmenschen, von Adam, abstammen, so müssen sie sich auch im Sinne des Paulus sagen: wie wir ohne unser Zutun durch die Verhältnisse, die in der physischen Menschheitsfortpflanzung gegeben sind, diese Linien zu Adam hinaufführen können, so muß es möglich sein, daß wir in uns etwas entstehen lassen können, was uns ein anderes möglich macht. Wie die natürlichen Linien zu Adam hinaufführen, so muß es möglich sein, Linien zu ziehen, die uns — zwar nicht zu dem fleischlichen Adam hinaufführen mit dem verweslichen Leib, die uns aber ebenso hinführen zu dem Leib, der unverweslich ist, und den wir durch unsere Beziehung zu dem Christus ebenso in uns tragen können, nach Paulinischer Auffassung, wie wir den verweslichen Leib durch Adam in uns tragen.

Nichts Unbequemeres gibt es für das moderne Bewußtsein, als diese Vorstellung. Denn ganz nüchtern besehen: was fordert das von uns? Es fordert etwas, was für das moderne Denken geradezu ungeheuerlich ist. Das moderne Denken hat lange darüber gestritten, ob alle Menschen von einem einzigen Urmenschen abstammen; aber das läßt es sich noch gefallen, daß alle Menschen von einem einzigen Menschen abstammen, der einmal auf der Erde da war für das physische Bewußtsein. Paulus aber fordert folgendes. Er sagt: Wenn du im rechten Sinne ein Christ werden willst, mußt du dir vorstellen, daß in dir etwas entstehen kann, was in dir leben kann, und von dem du sagen mußt, du kannst ebenso geistige Linien ziehen von diesem in dir Lebenden zu einem zweiten Adam, zu Christus, und zwar zu jenem Christus, der am dritten Tage sich aus dem Grabe erhoben hat, wie alle Menschen Linien hinziehen können zu dem physischen Leib des ersten Adam. — So verlangt Paulus von allen, die sich Christen nennen, daß sie in sich etwas entstehen lassen, was wirklich in ihnen ist, und was so, wie der verwesliche Leib zurückführt auf Adam, zu dem hinführt, was sich am dritten Tage erhoben hat aus dem Grabe, in das der Leib des Christus Jesus hineingelegt worden ist. Wer das nicht zugibt, kann kein Verhältnis zu Paulus gewinnen, kann nicht sagen: er verstehe Paulus. Stammt man ab in bezug auf seinen verweslichen Leib vom ersten Adam, so hat man die Möglichkeit, indem man die Wesenheit des Christus zu seinem eigenen Wesen macht, einen zweiten Stammvater zu haben. Das ist aber der, der sich am dritten Tage, nachdem der Leichnam des Christus Jesus in die Erde gelegt worden war, aus dem Grabe erhoben hat.

So sei uns zunächst klar, daß dies eine Forderung des Paulus ist, so unbequem es auch dem modernen Denken ist. Wir werden uns schon von dieser Paulinischen Aufstellung dem modernen Denken nähern; nur soll man keine andere Meinung haben über das, was uns aus Paulus so klar entgegentritt, soll nicht herumdeuteln an dem, was gerade bei Paulus so klar ausgesprochen ist. Es ist freilich bequem, etwas allegorisch auszulegen und zu sagen, er habe es so und so gemeint; aber alle diese Deutungen haben keinen Sinn. Und es bleibt uns nichts übrig, wenn wir einen Sinn damit verbinden wollen — selbst wenn das moderne Bewußtsein es als einen Aberglauben auffassen wollte — als daß nach Paulinischer Darstellung der Christus nach drei Tagen auferstanden ist. Gehen wir aber weiter.

Ich möchte hier nun auch noch die Bemerkung einfügen, daß eine solche Behauptung, wie sie Paulus getan hat, nachdem er selber den Gipfel seiner Initiation durch das Ereignis von Damaskus erlangt hatte, die Behauptung über den zweiten Adam und seine Auferstehung aus dem Grabe, nur einer machen konnte, der seiner ganzen Denkweise und seiner ganzen Anschauung nach aus dem Griechentum hervorgegangen war; der eben in dem Griechentum wurzelte, wenn auch als ein Angehöriger des hebräischen Volkes; der aber all seinen Hebräismus in gewisser Beziehung der griechischen Auffassung zum Opfer gebracht hatte. Denn was behauptet eigentlich Paulus, wenn wir der Sache nähertreten? Was die Griechen geliebt und geschätzt haben, die äußere Form des Menschenleibes, wovon sie die tragische Empfindung hatten: das endet, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes schreitet!, von dem sagt Paulus aus seiner Anschauung heraus: Es hat sich triumphierend aus dem Grabe erhoben mit der Auferstehung des Christus! — Und ziehen wir eine Brücke zwischen den zwei Weltanschauungen, so können wir sie am besten so ziehen:

Der griechische Heros sagte aus seiner griechischen Empfindung heraus: Lieber ein Bettler sein in der Oberwelt, als ein König im Reiche der Schatten! Und er sagte es, weil er aus seiner griechischen Empfindung heraus davon überzeugt war, daß das, was der Grieche liebte, die äußere Form des physischen Leibes, mit dem Durchgehen durch die Pforte des 'Iodes ein für allemal verloren sei. Auf denselben Boden, auf dem diese schönheitstrunkene tragische Stimmung erwachsen war, trat Paulus, der Verbreiter des Evangeliums zunächst unter den Griechen. Und wir weichen nicht von seinen Worten ab, wenn wir sie in folgender Weise übersetzen: «Nicht geht in der Zukunft das, was ihr am meisten schätzt, die menschliche Leibesform, zugrunde; sondern der Christus ist erstanden als der Erste von denen, die auferweckt werden von den Toten! Die physische Leibesform ist nicht verloren — sondern zurückgegeben der Menschheit durch die Auferstehung des Christus!» Was die Griechen am meisten schätzten, das gab der durch und durch griechisch gebildete Jude Paulus den Griechen mit der Auferstehung wieder zurück. Nur ein Grieche konnte so denken und so sprechen, aber nur ein Grieche, der es geworden war mit all den Voraussetzungen, die zugleich die Abstammung aus dem Judentum ergab. Nur ein zum Griechen gewordener Jude konnte so sprechen, nimmermehr ein anderer.

Wie können wir uns aber diesen Dingen vom Standpunkte der Geisteswissenschaft aus nähern? Denn vorerst sind wir erst so weit, daß wir wissen, Paulus habe etwas gefordert, was dem modernen Denken einen gründlichen Strich durch die Rechnung macht. Jetzt wollen wir einmal versuchen, uns vom Standpunkte der Geisteswissenschaft aus dem, was Paulus fordert, zu nähern.

Nehmen wir einmal die Dinge, die wir aus der Geisteswissenschaft wissen, zusammen, um aus dem, was wir selber sagen, eine Vorstellung zu bekommen gegenüber den Behauptungen des Paulus. Da wissen wir, wenn wir uns die allereinfachsten geisteswissenschaftlichen Wahrheiten noch einmal vor die Seele führen: Der Mensch besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich. Wenn Sie nun jemanden fragen, der sich ein wenig mit Geisteswissenschaft beschäftigt hat, aber nicht sehr gründlich, ob er den physischen Leib des Menschen kenne, so wird er Ihnen ganz gewiß sagen: Den kenne ich sehr gut; denn ich sehe ihn ja, wenn ein Mensch mir vor Augen tritt. Das andere sind die übrigen unsinnlichen, unsichtbaren Glieder, die kann man nicht sehen; aber den physischen Menschenleib kenne ich sehr gut. — Tritt uns wirklich der physische Leib des Menschen vor Augen, wenn wir mit unserer gewöhnlichen physischen Anschauung und unserem physischen Verstande dem Menschen entgegentreten? Ich frage Sie: Wer hat ohne hellseherische Anschauung jemals einen physischen Menschenleib gesehen? Was haben die Menschen vor Augen, wenn sie nur mit physischen Augen schauen und mit dem physischen Verstande begreifen? Ein Menschenwesen, das aber besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich! Und wenn ein Mensch vor uns steht, steht ein organisierter Zusammenhang aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich vor uns. Und es hat sowenig Sinn, zu sagen, es stünde ein physischer Leib vor uns, wie es keinen Sinn hätte, zu sagen, wenn wir jemandem ein Glas Wasser vorhalten: da ist Wasserstoff drinnen! Wasser besteht aus Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff, wie der Mensch besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich. Was physischer Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich zusammen ausmachen, das ist äußerlich in der physischen Welt zu sehen, wie das Wasser in dem Glase Wasser. Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff aber wird nicht gesehen, und der irrt sich gewaltig, der da sagen wollte, er würde den Wasserstoff im Wasser sehen. So irrt sich aber auch der, der da meint, er sehe den physischen Leib, wenn er einen Menschen in der äußeren Welt sieht. Nicht einen physischen Menschenleib sieht der mit physischen Sinnen und mit physischem Verstande begabte Beschauer, sondern ein viergliedriges Wesen — und den physischen Leib nur insofern, als er durchdrungen ist von den übrigen menschlichen Wesensgliedern. Da ist er aber so verändert, wie der Wasserstoff im Wasser, indem er vom Sauerstoff durchdrungen ist. Denn Wasserstoff ist ein Gas, und Sauerstoff ist auch eins. Wir haben also zwei Gase; beide zusammengefügt geben eine Flüssigkeit. Warum sollte es also unbegreiflich sein, daß der Mensch, der uns in der physischen Welt entgegentritt, sehr unähnlich ist seinen einzelnen Gliedern — dem physischen Leib, dem Ätherleib, dem Astralleib und dem Ich, wie ja auch das Wasser dem Wasserstoff sehr unähnlich ist? Und so ist es auch! Deshalb müssen wir sagen: Auf jene Maja, als die ihm der physische Leib zunächst erscheint, darf sich der Mensch nicht verlassen. Wir müssen uns den physischen Leib in einer ganz anderen Weise denken, wenn wir uns dem Wesen dieses physischen Menschenleibes nähern wollen.

Da handelt es sich darum, daß die Betrachtung des physischen Menschenleibes an sich zu den schwierigsten hellseherischen Problemen gehört, zu den allerschwierigsten! Denn nehmen wir an, wir lassen von der Außenwelt dasjenige Experiment mit dem Menschen vollziehen, das ähnlich ist dem Zerlegen des Wassers in Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff. Nun, im Tode wird ja dieses Experiment von der großen Welt vollzogen. Da sehen wir, wie der Mensch seinen physischen Leib ablegt. Legt er wirklich seinen physischen Leib ab? Die Frage scheint eigentlich lächerlich zu sein. Denn was scheint klarer zu sein, als daß der Mensch mit dem ’Iode seinen physischen Leib ablegt! Aber was der Mensch mit dem Tode ablegt — was ist denn das? Das ist etwas, von dem man zum mindesten sich sagen muß, daß es das Wichtigste, was der physische Leib im Leben hat, nicht mehr besitzt: nämlich die Form, die von dem Momente des Todes an zerstört zu werden beginnt an dem Abgelegten. Wir haben zerfallende Stoffe vor uns, und die Form ist nicht mehr eigentümlich. Was da abgelegt wird, sind im Grunde genommen die Stoffe und Elemente, die wir sonst auch in der Natur verfolgen; das ist nicht das, was sich naturgemäß eine menschliche Form geben würde. Zum physischen Menschenleib gehört aber diese Form ganz wesentlich. Für den gewöhnlichen hellseherischen Blick ist es zunächst tatsächlich so, als ob einfach der Mensch diese Stoffe ablege, die dann der Verwesung oder Verbrennung zugeführt werden, und sonst nichts von seinem physischen Leibe bliebe. Dann sieht das gewöhnliche Hellsehen nach dem Tode in jenen Zusammenhang hinein, der da besteht aus Ich, astralischem Leib und Ätherleib während der Zeit, während welcher der Mensch seinen Rückblik zum verflossenen Leben hat. Dann sieht der Hellseher durch das fortschreitende Experiment den Ätherleib sich abtrennen, sieht einen Extrakt dieses Ätherleibes mitgehen und das Übrige sich auflösen in dem allgemeinen Weltenäther in der einen oder anderen Weise. Und so scheint es in der 'Tat, als ob der Mensch den physischen Leib mit den physischen Stoffen und Kräften abgelegt hätte mit dem Tode und den Ärherleib nach ein paar Tagen. Und wenn der Hellseher den Menschen dann weiter verfolgt während der KamalokaZeit, so sieht er, wie wieder von dem Astralleib ein Extrakt durch das weitere Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt mitgenommen, und wie das andere des Astralleibes der allgemeinen Astralität übergeben wird.

Wir sehen also: Physischer Leib, Ätherleib und Astralleib werden abgelegt, und der physische Leib scheint erschöpft zu sein in dem, was wir vor uns haben in den Stoffen und Kräften, die der Verwesung oder Verbrennung oder auf eine andere Weise der Auflösung in die Elemente entgegengehen. Je mehr sich aber in unserer Zeit des Menschen Hellsichtigkeit entwickelt, desto mehr wird er sich über eines klar werden: daß das, was mit dem physischen Leibe abgelegt wird als die physischen Stoffe und Kräfte, doch nicht der ganze physische Leib ist, daß das gar nicht einmal die ganze Gestalt des physischen Leibes gäbe. Sondern zu diesen Stoffen und Kräften gehört noch etwas anderes, das wir nennen müssen, wenn wir sachgemäß sprechen, das «Phantom» des Menschen. Dieses Phantom ist die Formgestalt des Menschen, welche als ein Geistgewebe die physischen Stoffe und Kräfte verarbeitet, so daß sie in die Form hineinkommen, die uns als der Mensch auf dem physischen Plane entgegentritt. Wie der plastische Künstler keine Statue zustande bringt, wenn er Marmor oder irgend etwas anderes nimmt und wüst darauf losschlägt, daß einzelne Stücke abspringen, wie sie der Stoff eben abspringen läßt; sondern wie der plastische Künstler den Gedanken haben muß, den er dem Stoffe einprägt, so ist auch für den Menschenleib der Gedanke vorhanden; aber nicht so vorhanden, da das Material des Menschenleibes kein Marmor oder Gips ist, wie derjenige des Künstlers, sondern als der reale Gedanke in der Außenwelt: als Phantom. Was der plastische Künstler einprägt seinem Stoffe, das wird den Stoffen der Erde, die wir nach dem 'Iode dem Grabe oder dem Feuer übergeben sehen, eingeprägt als Phantom des physischen Leibes. Das Phantom gehört zum physischen Leibe dazu, es ist der übrige Teil des physischen Leibes, ist wichtiger als die äußeren Stoffe; denn die äußeren Stoffe sind im Grunde genommen nichts anderes als etwas, was hineingeladen wird in das Netz der menschlichen Form, wie man Äpfel auf einen Wagen lädt. Das Phantom ist etwas Wichtiges! Die Stoffe, die da zerfallen nach dem Tode, sind im wesentlichen das, was wir in der Natur draußen auch antreffen, nur daß es aufgefangen wird von der menschlichen Form.

Wenn Sie tiefer nachdenken: glauben Sie, daß alle die Arbeit, die getan worden ist von großen göttlichen Geistern durch die Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenzeit hindurch, nur das geschaffen hat, was mit dem ’Iode den Elementen der Erde übergeben wird? Nein! das ist es gar nicht, was da durch Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenzeit hindurch entwickelt worden ist. Das Phantom ist es, die Form des physischen Leibes! Das ist es also, worüber wir uns klar sein müssen, daß das Verständnis dieses physischen Leibes nicht so leicht ist. Vor allen Dingen darf das Verständnis des physischen Leibes nicht in der Welt der Illusion, nicht in der Welt der Maja gesucht werden. Wir wissen, daß den Grundstein, sozusagen den Keim zu diesem Phantom des physischen Leibes, die Throne während der Saturnzeit gelegt haben, daß dann weiter daran gearbeitet haben die Geister der Weisheit während der Sonnenzeit, die Geister der Bewegung während der Mondenzeit und die Geister der Form während der Erdenzeit. Und dadurch erst ist das, was der physische Leib ist, zum Phantom geworden. Daher nennen wir sie die Geister der Form, weil sie eigentlich in dem leben, was wir das Phantom des physischen Leibes nennen. So müssen wir schon, um den physischen Leib zu verstehen, zum Phantom desselben zurückgehen.

Nun würden wir also sagen können, wenn wir an den Beginn unseres Erdendaseins uns versetzen: Die Scharen aus den Reihen der höheren Hierarchien, welche über die Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenzeit bis zur Erdenzeit den menschlichen physischen Leib in seiner Form bereitet haben, sie haben dieses Phantom zunächst innerhalb der Erdenevolution hereingestellt. In der Tat war als erstes von dem physischen Leib des Menschen das Phantom da, das man nicht mit physischen Augen sehen kann. Das ist ein Kraftleib, der ganz durchsichtig ist. Was das physische Auge sieht, sind die physischen Stoffe, die der Mensch ißt, die er aufnimmt, und die dieses Unsichtbare ausfüllen. Schaut das physische Auge einen physischen Leib an, so sieht es in Wahrheit das Mineralische, das den physischen Leib ausfüllt, gar nicht den physischen Leib. Wodurch ist denn aber das Mineralische gerade so, wie es ist, hineingekommen in dieses Phantom des physischen Leibes des Menschen? — Um uns diese Frage zu beantworten, vergegenwärtigen wir uns noch einmal die Entstehung, das erste Werden des Menschen auf unserer Erde.

Herübergekommen ist von Saturn, Sonne und Mond jener Kraftzusammenhang, der uns im unsichtbaren Phantom des physischen Leibes in seiner wahren Gestalt entgegentritt, und der gerade für ein höheres Hellsehen erst als Phantom erscheinen wird, wenn wir absehen von alledem, was als äußere Stoffe dieses Phantom ausfüllt. Also dieses Phantom ist es, was am Ausgangspunkte steht. Unsichtbar wäre also der Mensch am Ausgangspunkte seines Erdenwerdens auch als physischer Leib. Nehmen wir jetzt an, es würde zu diesem Phantom des physischen Leibes der Ätherleib noch hinzugefügt werden, würde dadurch der physische Leib nun sichtbar werden als Phantom? Ganz gewiß nicht. Denn der Ätherleib ist sowieso unsichtbar für das gewöhnliche Anschauen. Also physischer Leib plus Ätherleib sind noch immer nicht sichtbar im äußeren physischen Sinne. Und der Astralleib erst recht nicht; so daß physischer Leib als Phantom und Ätherleib und Astralleib zusammen noch immer unsichtbar sind. Und das Ich, hinzugefügt, würde zwar innerlich wahrnehmbar sein, aber nicht äußerlich sichtbar. Also der Mensch bliebe uns, wie er aus der Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenzeit herübergekommen ist, etwas Unsichtbares, und würde nur für ein Hellsehen sichtbar sein. Wodurch wurde er sichtbar? — Er würde überhaupt nicht sichtbar geworden sein, wenn nicht das eingetreten wäre, was uns die Bibel symbolisch und was uns wirklich die Geheimwissen schaft schildert: der luziferische Einfluß. Was ist damit geschehen?

Lesen Sie nach in der «Geheimwissenschaft»: Aus jener Entwickelungsbahn, in welcher der Mensch dadurch war, daß sein physischer Leib, Ätherleib und Astralleib bis zum Unsichtbaren gebracht worden sind, ist er heruntergeworfen worden in die dichtere Materie und hat die dichtere Materie so aufgenommen, wie er sie eben aufnehmen mußte unter dem Einflusse des Luzifer. Wäre also in unserem astralischen Leibe und in unserem Ich nicht das, was wir die luziferische Kraft nennen, so würde die dichte Materialität nicht so sichtbar geworden sein, wie sie sichtbar geworden ist. Daher müssen wir sagen: Wir müssen den Menschen als einen unsichtbaren hinstellen; und erst mit den Einflüssen des Luzifer sind Kräfte in den Menschen eingezogen, die ihn für die Materie sichtbar machen. Durch die luziferischen Einflüsse geraten in das Gebiet des Phantoms die äußeren Stoffe und Kräfte und durchdringen dieses Phantom. Wie wenn wir in ein durchsichtig erscheinendes Glas eine farbige Flüssigkeit hineingießen, so daß uns dasselbe gefärbt erscheint, während es sonst für unser Auge durchsichtig war, so müssen wir uns denken, daß der luziferische Einfluß Kräfte hineingegossen hat in die menschliche Phantomform, wodurch der Mensch geeignet wurde, auf der Erde die entsprechenden Stoffe und Kräfte aufzunehmen, die seine sonst unsichtbare Form sichtbar werden lassen.

Was also macht den Menschen sichtbar? Die luziferischen Kräfte in seinem Innern machen den Menschen so sichtbar, wie er uns auf dem physischen Plane entgegentritt; sonst wäre sein physischer Leib immer unsichtbar geblieben. Daher haben die Alchimisten immer betont, daß der menschliche Leib in Wahrheit besteht aus derselben Substanz, aus welcher der ganz durchsichtige, kristallhelle Stein der Weisen besteht. Der physische Leib besteht wirklich aus absoluter Durchsichtigkeit, und die luziferischen Kräfte im Menschen sind es, welche ihn zur Undurchsichtigkeit gebracht haben und ihn so vor uns hinstellen, daß er undurchsichtig und greifbar wird. Daraus werden Sie ersehen, daß der Mensch zu dem Wesen, das die äußeren Stoffe und Kräfte der Erde aufnimmt, die mit dem Tode wieder weggegeben werden, nur dadurch geworden ist, daß er von Luzifer verführt worden ist, und daß gewisse Kräfte in seinen Astralleib hineingegossen worden sind. Was aber wird denn notwendigerweise daraus folgen? Daraus muß folgen, daß, indem das Ich unter dem Einfluß des Luzifer auf der Erde in den Zusammenhang von physischem Leib, Ätherleib und Astralleib eingezogen ist, der Mensch erst das geworden ist, was er auf der Erde ist. Dadurch ist er erst zum Träger der irdischen Gestalt geworden, sonst wäre er es nicht geworden.