The Bhagavad Gita and the Epistles of Paul

GA 142

31 December 1912, Cologne

Lecture IV

At the beginning of yesterday's lecture I pointed out how different are the impressions received by the soul when, on the one hand, it allows the well-balanced, calm, passionless, emotionless, truly wise nature of the Bhagavad Gita to work upon it, and on the other hand that which holds sway in the Epistles of St. Paul. In many respects these give the impression of being permeated by personal emotions, personal views and points of view, by a certain, for the whole collective evolution of man on earth, agitating sense of propagandism; they are even choleric, sometimes stormy. If we allow the manner in which the spiritual content of both is expressed to work upon us, we have in the Gita something so perfect, expressed in such a wonderful, artistically rounded way, that one could not well imagine a greater perfection of expression, revealed poetically and yet so philosophically. In the Epistles of St. Paul, on the other hand, we often find what one might call an awkwardness of expression, so that on account of this, which sometimes approaches clumsiness, it is extremely difficult to extract their deep meaning. Yet it is nevertheless true that that which relates to Christianity in the Epistles of St. Paul is the keynote for its development, just as the union of the world-conceptions of the East is the keynote of the Gita. In the Epistles of St. Paul we find the significant basic truths of Christianity as to the Resurrection, the significance of what is called Faith as compared with the Law, of the influence of grace, of the life of Christ in the soul or in the human consciousness, and many other things; we find all these presented in such a way that any presentation of Christianity must always be based on these Pauline Epistles. Everything in them refers to Christianity, as everything in the Gita refers to the great truths as to liberating oneself from works, to the freeing of oneself from the immediate life of action, in order to devote oneself to contemplation, to the meditation of the soul, to the upward penetration of the soul into spiritual heights, to the purification of the soul; in short, according to the meaning of the Gita, to the union with Krishna. All that has just been described makes a comparison of these two spiritual revelations extremely difficult, and anyone who merely makes an external comparison will doubtless be compelled to place the Bhagavad Gita, in its purity, calm and wisdom, higher than the Epistles of St. Paul. But what is a person who makes such an outward comparison actually doing? He is like a man who, having before him a fully grown plant, with a beautiful blossom, and beside it the seed of a plant; were to say: “When I look at the plant with its beautiful, fully-developed blossom, I see that it is much more beautiful than the insignificant, invisible seed.” Yet it might be that out of that seed lying beside the plant with the beautiful blossom, a still more beautiful plant with a still more beautiful blossom, might some day spring forth. It is really no proper comparison to compare two things to be found side by side, such as a fully-developed plant and a quite undeveloped seed; and thus it is if one compares the Bhagavad Gita with the Epistles of St. Paul. In the Bhagavad Gita we have before us something like the ripest fruit, the most wonderful and beautiful representation of a long human evolution, which had grown up during thousands of years and in the Epistles of St. Paul we have before us the germ of something completely new which must grow greater and greater, and which we can only grasp in all its full significance if we look upon it as germinal, and hold prophetically before us what it will some day become, when thousands and thousands of years of evolution shall have flowed into the future and that which is planted as a germ in the Pauline Epistles shall have grown riper and riper. Only if we bear this in mind can we make a proper comparison. It then also becomes clear that that which is some day to become great and which is first to be found in invisible form from the depths of Christianity in the Pauline Epistles, had once to pour forth in chaotic fashion from the human soul. Thus things must be represented in a different way by one who is considering the significance on the one hand of the Bhagavad Gita, and on the other of the Pauline Epistles for the whole collective evolution of man on earth, from the way they can be depicted by another person who can only judge of the complete works as regards their beauty and wisdom and inner perfection of form.

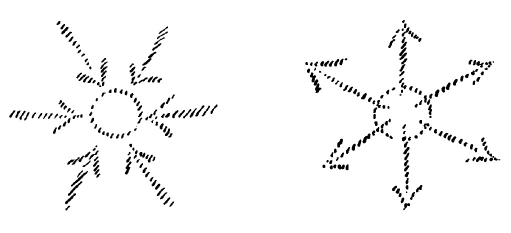

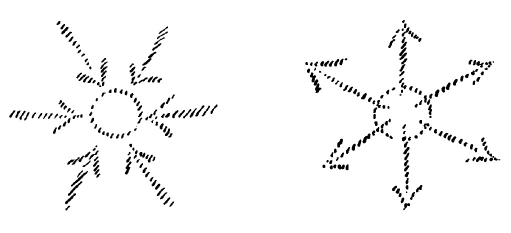

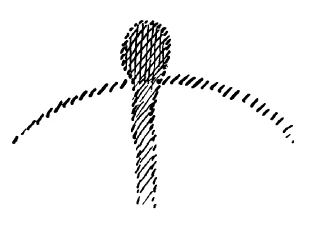

If we wish to draw a comparison between the different views of life which appear in the Bhagavad Gita and the Epistles of St. Paul, we must first inquire: What is the chief point in question? The point in question is that in all we are able to survey historically of the two views of life, what we are chiefly concerned with is the drawing down of the “ego” into the evolution of mankind. If we trace the ego through the evolution of mankind, we can say that in the pre-Christian times it was still dependent, it was still, as it were, rooted in concealed depths of the soul, it had not yet acquired the possibility of developing itself. Development of an individual character only became possible when into that ego was thrown, as it were, the impulse which we describe as the Christ-Impulse. That which since the Mystery of Golgotha may be within the human ego and which is expressed in the words of St. Paul: “Not I, but Christ in me,” that could not formerly be within it. But in the ages when there was already an approach to the Christ-Impulse—in the last thousand years before the Mystery of Golgotha—that which was about to take place through the introduction of the Christ-Impulse into the human soul was slowly prepared, particularly in such a way as that expressed in the act of Krishna. That which, after the Mystery of Golgotha, a man had to look for as the Christ-Impulse in himself, which he had to find in the Pauline sense: “Not I, but Christ in me,” that he had, before the Mystery of Golgotha, to look for outside, he had to look for it coming to him as a revelation from cosmic distances. The further we go back into the ages, the more brilliant, the more impulsive was the revelation from without. We may therefore say: In the ages before the Mystery of Golgotha, a certain revelation came to mankind like sunshine falling upon an object from without. Just as the light falls upon this object, so did the light of the spiritual sun fall from without upon the soul of man, and enlightened it. After the Mystery of Golgotha we can speak of that which works in the soul as Christ-Impulse, as the spiritual sunlight, as though we saw a self-illumined body before us radiating its light from within. If we look at it thus, the fact of the Mystery of Golgotha becomes a significant boundary line in human evolution. We can represent the whole connection, symbolically. If we take this circle (Diagram 1) as representing the human soul, we may say that the spiritual light streams in from without from all sides into this human soul. Then comes the Mystery of Golgotha, after which the soul possesses the Christ-Impulse in itself and radiates Forth that which is contained in the Christ-Impulse (Diagram 2). Just as a drop which is illumined from all sides radiates and reflects this illumination, so does the soul appear before the Christ-Impulse. As a flame which is alight within and radiates forth its light, thus does the soul appear after the Mystery of Golgotha, if it has been able to receive the Christ-Impulse.

Bearing this in mind we can express this whole relation by means of the terms we have learnt in Sankhya philosophy. We may say: If we direct our spiritual eye to a soul which, before the Mystery of Golgotha, is irradiated from all sides by the light of the spirit, and we see the whole connection of this spirit which pours in upon the soul from all sides radiating to us in its spirituality, the whole then appears to us in what the Sankhya philosophy describes as the Sattva condition. On the other hand, if we contemplate a soul after the Mystery of Golgotha had been accomplished, looking at it from outside as it were, with the spiritual eye, it seems as though the spiritual light were hidden away in its innermost depths and as if the soul-nature concealed it. The spiritual light appears to us as though veiled by the soul-substance, that spiritual light which, since the Mystery of Golgotha, is contained in the Christ-Impulse. Do we not perceive this verified up to our own age, indeed especially in our own age, with regard to all that man experiences externally? Observe a man today, see what he has to occupy himself with as regards his external knowledge and his occupation; and try to compare with this how the Christ-Impulse lives in man, as if hidden in his inmost being, like a yet tiny, feeble flame, veiled by the rest of the soul's contents. That is Tamas as compared with the pre-Christian state, which latter, as regards the relation of soul and spirit, was the Sattva-state. What part, therefore, in this sense does the Mystery of Golgotha play in the evolution of mankind? As regards the revelation of the spirit, it transforms the Sattva into the Tamas state. By means of it mankind moves forward, but it undergoes a deep fall, one may say, not through the Mystery of Golgotha, but through itself. The Mystery of Golgotha causes the flame to grow greater and greater: but the reason the flame appears in the soul as only a very small one—whereas before a mighty light poured in on it from all sides—is that progressing human nature is sinking deeper and deeper into darkness. It is not, therefore the fault of the Mystery of Golgotha that the human soul, as regards the spirit, is in the Tamas condition, for the Mystery of Golgotha will bring it to pass in the distant future that out of the Tamas condition a Sattva condition will again come about, which will then be set aflame from within. Between the Sattva and the Tamas condition there is, according to Sankhya philosophy, the Rajas condition; and this is described as being that time in human evolution in which falls the Mystery of Golgotha. Humanity itself, as regards the manifestation of the Spirit, went along the path from light into darkness, from the Sattva into the Tamas condition, just during the thousand years which surrounded the Mystery of Golgotha.

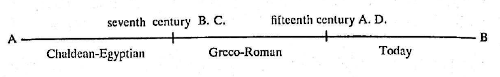

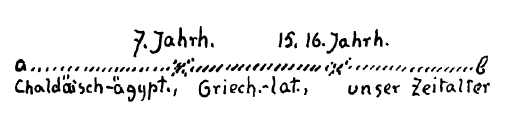

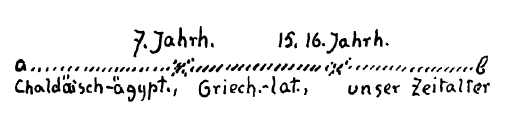

If we look more closely into this evolution, we may say: If we take the line a-b as the time of the evolution of mankind, up to about the eighth or seventh century before the Mystery of Golgotha, all human civilisation was then in the Sattva condition.

Then began the age in which occurred the Mystery of Golgotha, followed by our own age some fifteen or sixteen centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha. Then quite definitely begins the Tamas age, but it is a period of transition. If we wish to use our customary designations we have the first age—which, in a sense, as regards certain spiritual revelations, still belongs to the Sattva condition—occurring at the same epoch as that which we call the Chaldean-Egyptian, that which is the Rajas-condition is the Graeco-Latin, and that which is in the Tamas condition is our own age.' We know, too, that what is called the Chaldean-Egyptian age is the third of the Post-Atlantean conditions the Graeco-Latin the fourth, and our own the fifth. It was therefore necessary one might say, in accordance with the plan of the evolution of mankind, that between the third and fourth Post-Atlantean epochs there should occur a deadening, as it were, of external revelation. How was mankind really prepared for the blazing up of the Christ-Impulse? How did this preparation really occur?

If we want to make quite clear to ourselves the difference between the spiritual conditions of mankind in the third epoch of humanity—the Chaldean-Egyptian—and the following epochs, we must say: In this third age in all these countries, in Egypt as well as in Chaldea, and also in India, there still was in humanity the remains of the old clairvoyant power: that is to say, man not only saw the worlds around him with the assistance of his senses and of the understanding connected with the brain, but he could also still see the surrounding world with the organs of his etheric body, at any rate, under certain conditions, between sleeping and waking. If we wish to picture to ourselves a man of that epoch, we can only do so by saying: To those men a perception of nature and of the world such as we have through our senses and the understanding bound up with the brain was only one of the conditions which they experienced. In those conditions they gained as yet no knowledge, but merely, as it were, gazed at things and let them work, side by side in space and one after another in time. If these men wanted to acquire knowledge they had to enter a condition, not artificially produced as in our time, but occurring naturally, as if of itself, in which their deeper-lying forces, the forces of their etheric bodies, operated for producing knowledge. Out of knowledge such as this came forth all that appears as the wonderful knowledge of the Sankhya philosophy; from such a contemplation also went forth all that has come down to us in the Vedas—although that belongs to a still earlier age. Thus the man of that time acquired knowledge by putting himself or allowing himself to be put into another condition. He had so to say his everyday condition, in which he saw with his eyes, heard with his ears, and followed things with his ordinary understanding; but this seeing, hearing and understanding he only made use of when occupied in external practical business. It would never have occurred to him to make use of these capacities for the acquiring of knowledge. In order to acquire knowledge and perception he made use of what came to him in that other condition in which he brought into activity the deepest forces of his being.

We can therefore think of man in those old times as having, so to say, an everyday body, and within that everyday body his finer spiritual body, his Sunday body, if I may use such a comparison. With his everyday body he did his everyday work, and with his Sunday body—which was woven of the etheric body alone—he perceived and perfected his science. One would be justified in saying that a man of that olden time would be astonished that we in our day hew out our knowledge by means of our everyday body, and never put on our Sunday body when we wish to learn something about the world. Well, how did such a man experience all these conditions? The experiencing of these was such that when a man perceived by means of his deeper forces, when he was in that state of perception in which, for instance, he studied Sankhya philosophy, he did not then feel as does the man of today, who, when he wishes to acquire knowledge must exert his reason and think with his head. He, when he acquired knowledge, felt himself to be in his etheric body, which was certainly least developed in what today is the physical head, but was more pronounced in the other parts; man thought much more by means of the other parts of his etheric body. The etheric body of the head is the least perfect part of it. A man felt, so to say, that he thought with his etheric body; he felt himself when thinking, lifted out of his physical body; but at such moments of learning, of creative knowledge, he felt something more besides; he felt that he was in reality one with the earth. When he took off his everyday body and put on his Sunday body, he felt as though forces passed through his whole being; as though forces passed through his legs and feet and united him to the earth, just as the forces which pass through our hands and arms unite them with our body. He began to feel himself a member of the earth. On the one hand, he felt that he thought and knew in his etheric body, and on the other he felt himself no longer a separate man, but a member of the earth. He felt his being growing into the earth. Thus the whole inner manner of experiencing altered when a man drew on his Sunday body and prepared himself for knowledge. What, then, had to happen in order that this old old age—the third—should so completely cease, and the new age—the fourth—should come in? If we wish to understand what had to happen then, it would be well to try to feel our way a little into the old method of description.

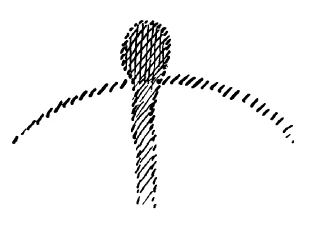

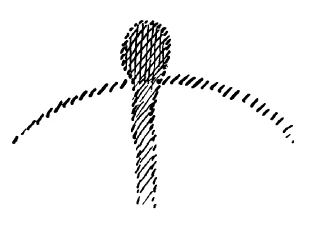

A man who in that olden time experienced what I have just described, would say: “The serpent has become active within me.” His being lengthened out into the earth; he no longer felt his physical body as the really active part of him; he felt as though he stretched out a serpent-like continuation of himself into the earth and the head was that which projected out of the earth. And he felt this serpent being to be the thinker. We might draw the man's being thus: his etheric body passing into the earth, elongated into a serpent-body and, whilst outside the earth as physical man, he was stretched down into the earth during the time of perceiving and knowing, and thought with his etheric body.

“The serpent is active within me,” said he. To perceive was therefore in the olden time something like this: “I rouse the serpent within me to a state of activity; I feel my serpent-nature.” What had to happen, so that the new age should come in, that the new method of

perceiving should come about? It had to be no longer possible for those moments to occur in which man felt his being extended down into the earth through his legs and feet; besides which perception had to die out in his etheric body and pass over to the physical head. If you can rightly picture this passing over of the old perception into the new, you will say: a good expression for this transition would be: “I am wounded in the feet, but with my own body I tread under foot the head of the serpent,” that is to say, the serpent with its head ceases to be the instrument of thought. The physical body and especially the physical brain, kills the serpent, and the serpent revenges itself by taking away from one the feeling of belonging to the earth. It bites one in the heel.

At such times of transition from one form of human experience into another, that which comes, as it were, from the old epoch, comes into conflict with that which is coming in the new epoch; for these things are still really contemporaneous. The father is still in existence long after the son's life has begun; although the son is descended from the father. The attributes of the fourth epoch, the Graeco-Latin were there, but those of the third, the Egyptian-Chaldean epoch, still stirred and moved in men and in nations. These attributes naturally became intermingled in the course of evolution, but that which thus appears as the newly-arisen, and that which comes, as it were, out of the olden times, continue to live contemporaneously, but can no longer understand each other properly. The old does not understand the new. The new must protect itself against the old, must defend its life against it; that is to say, the new is there, but the ancestors with their attributes belonging to the old epoch, still work in their descendants, the ancestors who have taken no part in the new. Thus we may describe the transition from the third epoch of humanity to the fourth. There had therefore to be a hero, as we might say—a leader of humanity who, in a significant manner, first represents this process of the killing of the serpent, of being wounded by it; while he had at the same time to struggle against that which was certainly related to him, but which with its attributes still shone into the new age from the old. In the advance of mankind, one person must first experience the whole greatness of that which later all generations experience. Who was the hero who crushed the head of the serpent, who struggled against that which was important in the third epoch? Who was he who guided mankind out of the old Sattva-time into the new Tamas-time? That was Krishna-and how could this be more clearly shown than by the Eastern legend in which Krishna is represented as being a son of the Gods, a son of Mahadeva and Devaki, who entered the world surrounded by miracles (that betokens that he brings in something new), and who, if I may carry my example further, leads men to look for wisdom in their everyday body, and who crushes their Sunday body—the serpent; who has to defend himself against that which projects into the new age from his kindred. Such a one is something new, something miraculous. Hence the legend relates how the child Krishna, even at his birth, was surrounded by miracles, and that Kansa, the brother of his mother, wished to take the life of the child. In the uncle of the child Krishna we see the continuance of the old, and Krishna has to defend himself against him; for Krishna had to bring in the new, that which kills the third epoch and does away with the old conditions for the external evolution of mankind. He had to defend himself against Kansa, the inhabitant of the old Sattva age; and amongst the most remarkable of the miracles with which Krishna is surrounded, the legend relates that the mighty serpent Kali twined round him, but that he was able to tread the head of the serpent under foot, though it wounded his heel. Here we have something of which we may say the legend directly reproduces an occult fact. That is what legends do; only we ought not to seek an external explanation, but should grasp the legend aright, in the true light of knowledge, in order to understand it.

Krishna is the hero of the setting third Post-Atlantean epoch of humanity. The legend relates further that Krishna appeared at the end of the third cosmic epoch. It all corresponds when rightly understood. Krishna is therefore he who kills out the old perception, who drives it into the darkness. This he does in his external phenomena; he reduces to a state of darkness that which as Sattva-knowledge, was formerly possessed by mankind. Now, how is he represented in the Bhagavad Gita? He is there represented as giving to a single individual, as if in compensation for what he has taken away from him, guidance as to how through Yoga he can rise to that which was then lost to normal mankind. Thus to the world Krishna appears as the killer of the old Sattva-knowledge, while at the same time we see him at the end of the Gita as the Lord of Yoga, who is again to lead us up to the knowledge which had been abandoned; the knowledge belonging to the old ages, which we can only attain when we have overcome and conquered that which we now put on externally as an everyday dress; when we return once more to the old spiritual condition. That was the twofold deed of Krishna, He acted as a world-historical hero, in that he crushed the head of the serpent of the old knowledge and compelled man to re-enter the physical body, in which alone the ego could be won as free and independent ego, whereas formerly all that made man an ego streamed in from outside. Thus he was a world-wide historical Hero. Then to the individual he was the one who for the times of devotion, of meditation, of inner finding, gave back that which had at one time been lost. That it is which we meet with in such a grand form in the Gita, which at the end of our last lecture we allowed to work upon our souls, and which Arjuna meets as his own being seen externally; seen without beginning and without end—outspread over all space.

If we observe this condition more clearly we come to a place in the Gita which, if we have already been amazed at the great and mighty contents of the Gita, must infinitely extend our admiration. We come to a passage which, to the man of the present day, must certainly appear incomprehensible; wherein Krishna reveals to Arjuna the nature of the Avayata-tree, of the Fig-tree, by telling him that in this tree the roots grow upwards and the branches downwards; where Krishna further says that the single leaves of this tree are the leaves of the Veda book, which, put together, yield the Veda knowledge. That is a singular passage in the Gita. What does it signify, this pointing to the great tree of Life, whose roots have an upward direction, and the branches a downward direction, and whose leaves give the contents of the Veda? We must just transport ourselves back into the old knowledge, and try and understand how it worked. The man of today only has, so to say, his present knowledge, communicated to him through his physical organs. The old knowledge was acquired as we have just described, in the body which was still etheric, not that the whole man was etheric, but knowledge was acquired through the part of the etheric body which was within the physical body. Through this organism, through the organisation of the etheric body, the old knowledge was acquired. Just imagine vividly that you, when in the etheric body, could perceive by means of the serpent. There was something then present in the world, which to the man of the present day is no longer there. Certainly the man of today can realise much of what surrounds him when he puts himself into relation with nature; but just think of him when he is observing the world: there is one thing he does not perceive, and that is his brain. No man can see his own brain when he is observing; neither can any man see his own spine. This impossibility ceases as soon as one observes with the etheric body. A new object then appears which one does not otherwise see—one perceives one's own nervous system. Certainly it does not appear as the present-day anatomist sees it. It does not appear as it does to such a man, it appears in such a way that one feels: “Yes! There thou art, in thy etheric nature.” One then looks upwards and sees how the nerves, which go through all the organs, are collected together up there in the brain. That produces the feeling: “That is a tree of which the roots go upwards, and the branches stretch down into all the members.” That in reality is not felt as being of the same small size as we are inside our skin: it is felt as being a mighty cosmic tree. The roots stretch far out into the distances of space and the branches extend downwards. One feels oneself to be a serpent, and one sees one's nervous system objectified, one feels that it is like a tree which sends its roots far out into the distance of space and the branches of which go downwards. Remember what I have said in former lectures, that man is, in a sense, an inverted plant. All that you have learnt must be recalled and put together, in order to understand such a thing as this wonderful passage in the Bhagavad Gita. We are then astonished at the old wisdom which must today, by means of new methods, be called forth from the depths of occultism. We then experience what this tree brings to light. We experience in its leaves that which grows upon it; the Veda knowledge, which streams in on us from without.

The wonderful picture of the Gita stands out clearly before us: the tree with its roots going upwards, and its branches going downwards, with its leaves full of knowledge, and man himself as the serpent round the tree. You may perhaps have seen this picture, or have come across the picture of the Tree of Life with the serpent; everything is of significance when one considers these old things. Here we have the tree with the upward growing roots, and the downward-turning branches; one feels that it goes in an opposite direction to the Paradise-tree. That has its deep meaning: for the tree of Paradise is placed at the beginning of the other evolution, that which through the old Hebrew antiquity passes on into Christianity. Thus in this place we are given an indication of the whole nature of that old knowledge, and when Krishna distinctly says to his pupil Arjuna “Renunciation is the power which makes this tree visible to mankind,” we are shown how man returns to that old knowledge when he renounces everything acquired by him in the further course of evolution, which we described yesterday. That it is which is given as something grand and glorious by Krishna to his only individual pupil Arjuna as a payment on account, whilst he has to take it from the whole of humanity for the everyday use of civilisation. That is the being of Krishna. What then must that become which Krishna gives to his single individual pupil? It must become Sattva wisdom; and the better he is able to give him this Sattva wisdom, the wiser, clearer, calmer and more passionless will it be, but it will be an old revealed wisdom, something which approaches mankind from without in such a wonderful way in the words which the Sublime One, that is to say, Krishna Himself, speaks, and in those in which the single individual pupil makes reply. Thus Krishna becomes the Lord of Yoga, who leads us back to the ancient wisdom of mankind, and who always endeavours to overcome that, which even in the age of the Sattva, concealed the spirit from the soul, who wishes to bring before his pupil the spirit in its ancient purity, as it was before it descended into substance. Thus in the spirit only does Krishna appear to us in that mutual conversation between Krishna and his pupil to which we referred yesterday.

Thus we have brought before our souls the end of that epoch, which was the last one of the ages of the old spirituality; that spirituality that we can so follow that we see its full and complete spiritual light at its beginning, and then its descent into matter in order that man should find his ego, his independence. And when the spiritual light had descended as far as the fourth Post-Atlantean epoch, there was then a sort of reciprocal relationship, a Rajas relationship between the spirit and the more external soul-part. In this epoch occurred the Mystery of Golgotha. Could we describe this epoch as belonging to the Sattva-condition? No! For then we should not be describing just what belonged to that epoch! If anyone describes it correctly, as belonging to the Rajas-age—making use of that expression of Sankhya philosophy—he must describe it according to Rajas, not in terms of purity and clearness, but in a personal sense, as aroused to anger about this, or that, and so on. Thus would one have to describe it, and thus did St. Paul portray it, in the sense of its relation to Rajas. If you feel the throbbing of many a saying in the Epistles to the Thessalonians, to the Corinthians, or to the Romans, you will become aware of something akin to rage, something often like a personal characteristic pulsating in the Epistles of St. Paul, wrenching itself away from the Rajas-condition—that is the style and character of these Epistles. They had to appear thus; whereas the Bhagavad Gita had to come forth clear and free from the personal because it was the finest blossom of the dying epoch, which, however, gave one individual a compensation for that which was going under, and led him back into the heights of spiritual life. Krishna had to give the finest spiritual blossoms to his own pupil, because he was to kill out the old knowledge of mankind, to crush the head of the serpent. This Sattva-condition went under of itself, it was no longer there; and anyone, in the Rajas age who spoke of the Sattva-condition spoke only of that which was old. He who placed himself at the beginning of the newer age had to speak in accordance with what was decisive for that time. Personality had drawn into human nature because human nature had found the way to seek knowledge through the organs and instruments of the physical body. In the Pauline Epistles the personal element speaks; that is why a personality thunders against all that draws in as the darkness of the material; with words of wrath he thunders forth, for words of wrath often thunder forth in the Epistles of St. Paul. That is why the Epistles of St. Paul cannot be given in the strictly limited lines, in the sharply-defined, wise clearness of the Bhagavad Gita.

The Bhagavad Gita can speak in words full of wisdom because it describes how man may free himself from external activity, and raise himself in triumph to the spirit, how he may become one with Krishna. It could also describe in words full of wisdom the path of Yoga, which leads to the greatest heights of the soul. But that which came into the world as something new, the victory of the spirit over that which merely pertains to the soul within, that could at first only be described out of the Rajas-condition; and he who first described it in a manner significant for the history of mankind, does so full of enthusiasm; in such a way that one knows he took part in it himself, that he himself trembled before the revelation of the Christ-Impulse. The personal had then come to him, he was confronted for the first time with that which was to work on for thousands of years into the future, it came to him in such a way that all the forces of his soul had to take a personal part in it. Therefore he does not describe in philosophic concepts, full of wisdom, such as occur in the Bhagavad Gita, but describes what he has to describe as the resurrection of Christ as something in which man is directly and personally concerned.

Was it not to become personal experience? Was not Christianity to draw into what is most intimately personal, warm it through and through, and fill it with life? Truly he who described the Christ-Event for the first time could only do so as a personal experience. We can see how in the Gita the chief emphasis is laid upon the ascent through Yoga into spiritual heights; the rest is only touched upon in passing. Why is this? Because Krishna only gives his instructions to one particular pupil and does not concern himself with what other people outside in the world feel as to their connection with the spiritual. Therefore Krishna describes what his pupil must become, that he must grow higher and higher, and become more and more spiritual. That description leads to riper and riper conditions of the soul, and hence to more and more impressive pictures of beauty. Hence also it is the case that only at the end do we meet with the antagonism between the demoniacal and the spiritual, and it confirms the beauty of the ascent into the soul-life; only at the conclusion do we see the contrast between those who are demoniacal and those who are spiritual. All those people out of whom only the material speaks, who live in the material, who believe that all comes to an end with death, are demoniacal. But that is only mentioned by way of enlightenment, it is nothing with which the great teacher is really concerned: he is before all concerned with the spiritualising of the human soul. Yoga may only speak of that which is opposed to Yoga, as a side-issue. St. Paul is, above all, concerned with the whole of humanity, that humanity which is in fact in the oncoming age of darkness. He has to turn his attention to all that this age of darkness brings about in human life; he must contrast the dark life, common to all, with that which is the Christ-Impulse, and which is first to spring up as a tiny plant in the human soul. We can see it appearing in St. Paul as he points over and over again to all sorts of vice, all sorts of materialism, which must be combated through what he has to give. What he is able to give is at first a mere flickering in the human soul, which can only acquire power through the enthusiasm which lies behind his words, and which appears in triumphant words as the manifestation of feeling through personality. Thus the presentations of the Gita and of the Pauline Epistles are far removed from each other; in the clearness of the Gita the descriptions are impersonal, while St. Paul had to work the personal into his words. It is that which on the one hand gives the style, and tone to the Gita, and on the other to the Pauline Epistles; we meet it in both works, almost, one might, say in every line. Something can only attain artistic perfection when it has acquired the necessary ripeness; at the beginning of its development it always appears as more or less chaotic.

Why is all this so? This question is answered if we turn to the wonderful beginning of the Gita. We have already described it; we have seen the hosts of the kindred facing each other in battle, one warrior facing another, yet both conqueror and conquered are related to one another by blood. The time we are considering is that of the transition from the old blood-relationship, to which belongs the power of clairvoyance-to that of the differentiation and mingling of blood which is the characteristic of our modern times. We are confronted with a transformation of the outer bodily nature of man and of the perception which necessarily accompanies this. Another kind of mingling of blood, a new significance of blood now enters into the evolution of mankind. If we wish to study the transition from that old epoch to the new—I would remind you of my little pamphlet, The Occult Significance of Blood—we must say that the clairvoyance of olden times depended upon the fact that the blood was, so to say, kept in the tribe, whereas the new age proceeded from the mixing of blood by which clairvoyance was killed, and the new perception arose which is connected with the physical body. The beginning of the Gita points to something external, to something connected with man's bodily form. It is with these external changes of form that Sankhya philosophy is mostly concerned; in a sense it leaves in the background that which belongs to the soul, as we have pointed out. The souls in their multiplicity are simply behind the forms. In Sankhya philosophy we have found a kind of plurality; we have compared it with the Leibnitz philosophy of more modern times.

If we can think ourselves into the soul of a Sankhya philosopher, we can imagine his saying: “My soul expresses itself in the Sattva or in the Rajas or in the Tamas condition with respect to the forms of the external body.” But this philosopher studies the forms. These forms alter, and one of the most remarkable changes is that which expresses itself in the different use made of the etheric body, or through the transition as regards blood-relationship we have just described. We have then an external change of form. The soul itself is not in the least affected by that with which Sankhya philosophy concerns itself. The external changes of form are quite sufficient to enable us to consider what takes place in the transition from the old Sattva age to that of the new Rajas, on the borders of which stands Krishna. It is the external changes of form which come into consideration there.

Outer changes of form always come into consideration at the time of the change of the ages. But the changes of form took place in a different way during the transition from the Persian to the Egyptian epoch from what they did in that from the Egyptian to the Graeco-Latin; still an external change of form did take place. In yet another manner took place the transition from the Ancient Indian to the Persian, but there too there was an external change of form. Indeed it was simply a change of form which occurred when the passing-over from the old Atlantis itself into the Post-Atlantean ages took place. A change of form: and we could follow this by holding fast to the designations of the Sankhya philosophy, we can follow it simply by saying: The soul goes through its experiences within these forms, but the soul itself is not altered thereby, Purusha remains undisturbed. Thus we have a particular sort of transformation which can be described by Sankhya philosophy according to its own conceptions. But behind this transforming there is Purusha, the individual part of the soul of every man. The Sankhya philosophy only says of this that there is an individual soul-part which is related through the three Gunas-Sattva, Rajas and Tamas—with external form. But this soul-part is not itself affected by the external forms; Purusha is behind them all and we are directed to the soul itself; a continual indication of the soul itself is what meets us in the teaching of—Krishna, in what he as Lord of Yoga teaches. Yes, certainly I but the nature of this soul is not given us in the way of knowledge. Directions as to how to develop the soul is the highest we are shown; alteration of the external forms; no change in the soul itself, only an introductory note.

This first suggestion we discover in the following way if man is to rise through Yoga from the ordinary stages of the soul to the higher, he must free himself from external works, he must emancipate himself more and more from outer works, from what he does and perceives externally; he must become a “looker-on” at himself. His soul then assumes an inner freedom and raises itself triumphantly over what is external. That is the case with the ordinary man, but with one who is initiated and becomes clairvoyant the case does not remain thus; he is not confronted with external substance, for that in itself is maya. It only becomes a reality to him who makes use of his own inner instruments. What takes the place of substance? If we observe the old initiation we meet with the following: Whereas man in everyday life is confronted with substance, with Prakriti—the soul which through Yoga has developed itself by initiation, has to fight against the world of the Asuras, the world of the demoniacal. Substance is what offers resistance; the Asuras, the powers of darkness become enemies. But all that is as yet a mere suggestion, we perceive it as something peeping out of the soul, so to say; we begin to feel that which pertains to the soul. For the soul will only begin to realise itself as spiritual when it begins to fight the battle against the demons, the Asuras.

In our language we should describe this battle, which, however, we only meet with in miniature, as something which becomes perceptible in the form of spirits, when substance appears in spirituality. We thus perceive in miniature that which we know as the battle of the soul when it enters upon initiation, the battle with Ahriman. But when we look upon it as a battle of this kind, we are then in the innermost part of the soul, and what were formerly material spirits grow into something gigantic; the soul is then confronted with the mighty foe. Soul then stands up against Soul, the individual soul in universal space is confronted with the realm of Ahriman. It is the lowest stage of Ahriman's kingdom with which one fights in Yoga; but now when we look at this as the battle of the soul with the powers of Ahriman, with Ahriman's kingdom, he himself stands before us. Sankhya philosophy recognises this relationship of the soul to external substance, in which the latter has the upper hand, as the condition of Tamas. The initiate who has entered initiation by means of Yoga is not only in this Tamas state, but also in battle with certain demoniacal powers, into which substance transforms itself before his sight. In this same sense the soul, when it is in the condition not only of being confronted with the spiritual in substance, but with the purely spiritual, is face to face with Ahriman. According to Sankhya philosophy, spirit and matter are in balance in the Rajas condition, they sway to and fro, first matter is above, then spirit, at one time matter weighs down the scales, then spirit. If this condition is to lead to initiation, it must lead in the sense of the old Yoga to a direct overcoming of Rajas, and lead into Sattva. To us it does not yet lead into Sattva, but to the commencement of another battle-the battle with what is Luciferic.

And now the course of our considerations leads us to Purusha, which is only hinted at in Sankhya philosophy. Not only do we hint at it, we place it right in the midst of the field of the battle against Ahriman and Lucifer: one soul-nature wars against another. In Sankhya philosophy Purusha is seen in immense perspective; but if we enter more deeply into that which plays its part in the nature of the soul, not as yet distinguished between Ahriman and Lucifer; then in Sattva, Rajas and Tamas we only find the relation of the soul to material substance. But considering the matter in our own sense, we have the soul in its full activity, fighting and struggling between Ahriman and Lucifer.

That is something which, in its full greatness can only be considered through Christianity. According to the old Sankhya teaching Purusha remains still undisturbed: it describes the condition which arises when Purusha clothes itself in Prakriti. We enter the Christian age and in that which underlies esoteric Christianity and we penetrate into Purusha itself, and describe this by taking the trinity into consideration: the soul, the Ahrimanic, and the Luciferic. We now grasp the inner relationship of the soul itself in its struggles. That which had to come was to be found in the transition in the fourth epoch, that transition which is marked through the Mystery of Golgotha. For what took place then? That which occurred in the transition from the third to the fourth epoch was something which can be described as a mere change of form; but now it is something which can only be described by the transition from Prakriti into Purusha itself, which must be so characterised that we say: “We feel how completely Purusha has emancipated itself from Prakriti, we feel that in our innermost being.”

Man is not only torn away from the ties of blood, but also from Prakriti, from everything external, and must inwardly have done with it. Then comes the Christ-Impulse. That is, however, the greatest transition which could take place in the whole evolution of the earth. It is then no longer merely a question of what might be the conditions of the soul in relation to matter, in Sattva, Rajas and Tamas, for the soul no longer has merely to overcome Tamas and Rajas to raise itself above them in Yoga, but has to fight against Ahriman and Lucifer, for it is now left to itself. Hence the necessity to confront that which is presented to us in that mighty Poem—the Bhagavad Gita—that which was necessary for the old times-with that which is necessary for the new.

That sublime Song, the Bhagavad Gita, shows us this conflict. There we are shown the human soul. It dwells in its bodily part, in its sheaths. These sheaths can be described. They are that which is in a constant state of changing form. The soul in its ordinary life lives in a state of entanglement, in Prakriti, In Yoga it frees itself from that which envelopes it, it overcomes that in which it is enwrapped, and enters the spiritual sphere, when it is quite free from its coverings. Let us compare with this that which Christianity, the Mystery of Golgotha, first brought. It is not here sufficient that the soul should merely make itself free. For if the soul should free itself through Yoga, it would attain to the vision of Krishna. He would appear in all his might before it, but as he was before Ahriman and Lucifer obtained their full power. Therefore a kind divinity still conceals the fact that beside Krishna—who then becomes visible in the sublime way described in our last lecture—on his left and on his right there stand Ahriman and Lucifer. With the old clairvoyance that was still possible, because man had not yet descended into matter; but now it can no longer be the case. If the soul were now only to go through Yoga it would meet Ahriman and Lucifer and would have to enter into battle with them. It can only take its place beside Krishna when it has that ally Who fights Ahriman and Lucifer; Tamas and Rajas would not suffice. That ally, however, is Christ. Thus we see how that which is of a bodily nature freed itself from the body, or one might also say, that which is bodily darkened itself within the body, at the time when Krishna, the Hero, appeared. But, on the other hand, we see that which is still more stupendous; the soul abandoned to itself and face to face with something which is only visible in its own domain in the age in which the Mystery of Golgotha occurred.

I can well imagine, my dear friends, someone saying: “Well, what could be more wonderful than when the highest ideal of man, the perfection of mankind, is placed before our eyes in the form of Krishna!” There can be something higher—and that it is which must stand by our side and permeate us when we have to gain this humanity, not merely against Tamas and Rajas, but against the powers of the spirit. That is the Christ. So it is the want of capacity to see something greater still, if one is determined to see in Krishna the highest of all. The preponderating force of the Christ-Impulse as compared with the Krishna-Impulse is expressed in the fact that in the latter we have incarnated in the whole human nature of Krishna, the Being which was incarnated in him. Krishna was born, and grew up, as the son of Visudeva; but in his whole manhood was incorporated, incarnated, that highest human impulse which we recognise as Krishna. That other Impulse, which must stand by our side when we have to confront Lucifer and Ahriman (which confrontation is only now beginning, for all such things, for instance, as are represented in our Mystery Dramas, will be understood psychically by future generations), that other Impulse must be one for which mankind as such, is at first too small, an Impulse which cannot immediately dwell even in a body such as one which Zarathustra can inhabit, but can only dwell in it when that body itself has attained the height of its development, when it has reached its thirtieth year. Thus the Christ-Impulse does not fill a whole life, but only the ripest period of a human life. That is why the Christ-Impulse lived only for three years in the body of Jesus. The more exalted height of the Christ-Impulse is expressed in the fact that it could not live immediately in a human body, as did Krishna from his birth up. We shall have to speak further of the overwhelming greatness of the Christ-Impulse as compared with the Krishna. Impulse and how this is to be seen. But from what has already been characterised you can both see and feel that, as a matter of fact, the relation between the great Gita and the Epistles of St. Paul could be none other; that the whole presentation of the Gita being the ripe fruit of much, much earlier times, may therefore be complete in itself; while the Epistles of St. Paul, being the first seeds of a future-certainly more perfect, more all-embracing world-epoch, must necessarily be far more incomplete. Thus one who represents how the world runs its course must recognise, it is true, the great imperfections of the Pauline Epistles as compared with the Gita, the very, very significant imperfections—they must not be disguised—but he must also understand the reason those imperfections have to be there.

Vierter Vortrag

Es ist schon gestern im Beginne des Vortrags darauf hingewiesen worden, wie verschieden die Eindrücke sind, die unsere Seele bekommt, wenn sie auf der einen Seite das ausgeglichene, gelassene, leidenschaftslose und affektlose, wahrhaft weise Wesen der Bhagavad Gita auf sich wirken laßt und auf der anderen Seite das, was in den Paulusbriefen waltet, die in vieler Beziehung den Eindruck machen, daß sie von persönlichen Leidenschaften, von persönlichen Absichten und Ansichten durchdrungen sind, durchdrungen sind von einem gewissen agitatorischen, propagandistischen Sinn, daß sie zornmütig sogar sind, zuweilen polternd. Und wenn man gar die Art und Weise auf sich wirken laßt, wie der Geistesinhalt zum Ausdruck kommt, dann hat man in der Gita in einer wunderbar künstlerisch gerundeten Form so Vollkommenes, daß man sich wohl kaum gesteigert denken kann diese Vollkommenheit des Ausdruckes dessen, was da dichterisch geoffenbart wird und doch so philosophisch ist. In den Paulusbriefen hat man dagegen oftmals, man möchte sagen, eine Ungelenkigkeit des Ausdrucks, so daß es außerordentlich schwierig wird gegenüber dieser Ungelenkigkeit, die zuweilen wie Unbeholfenheit erscheint, den tiefen Sinn erst herauszugewinnen.

Bei alledem bleibt es richtig, daß in den Paulusbriefen das, worauf es im Christentum ankommt, ebenso tonangebend für die Entwickelung des Christentums hingestellt sich findet, wie der Zusammenklang orientalischer Weltanschauungen uns in der Gita tonangebend entgegentritt. Finden wir doch in den Paulusbriefen die grundbedeutsamen Wahrheiten des Christentums von der Auferstehung, von der Bedeutung dessen, was man den Glauben nennt gegenüber dem Gesetz, von der Gnadenwirkung, von dem Leben des Christus in der Seele oder im menschlichen Bewußtsein und vieles andere. Findet man doch das alles so hingestellt, daß immer wieder und wiederum bei einer Darstellung des Christentums von diesen Paulusbriefen ausgegangen werden muß.

Alles ist bei den Paulusbriefen in bezug auf das Christentum so, wie es in der Bhagavad Gita ist in bezug auf die großen Wahrheiten vom Frei-Werden vom Werke, vom Sich-Herauslösen vom unmittelbar tätigen Leben zur Betrachtung der Dinge, zur Versenkung der Seele, zum Hinaufdringen der Seele in geistige Höhen, zur Reinigung der Seele, kurz, wenn wir im Sinne dieser Gita reden, zur Vereinigung mit Krishna.

Alles dies, was da eben charakterisiert wurde, macht einen Vergleich der beiden Geistesoffenbarungen außerordentlich schwierig, und wer nur äußerlich vergleicht, der wird ja ohne Zweifel die Bhagavad Gita in ihrer Reinheit und Gelassenheit und Weisheit höher stellen müssen als die Paulusbriefe. Aber wer so äußerlich vergleicht, was macht denn der eigentlich? Er macht etwas Ähnliches, wie jemand, der vor sich hat eine voll ausgewachsene Pflanze mit einer schönen Blüte, mit einer herrlichen Blüte, und daneben liegen hat einen Pflanzenkeim und der dann sagt: Wenn ich da vor mir habe die Pflanze mit der vollausgebildeten, herrlichen Blüte, so ist diese doch etwas weit Schöneres als der unscheinbare, nichtssagende Pflanzenkeim. — Und doch könnte die Sache eben so liegen, daß aus diesem Pflanzenkeim, der neben der Pflanze mit der wunderschönen Blüte liegt, einmal herauswachsen soll eine noch schönere Pflanze mit einer noch schöneren Blüte. Und man hat eben keinen richtigen Vergleich gemacht, wenn man so unmittelbar das vergleicht, was nebeneinander liegt wie eine ausgebildete Pflanze und ein ganz unausgebildeter Keim. Und so ist es, wenn man die Bhagavad Gita mit den Paulusbriefen vergleicht.

In der Bhagavad Gita hat man etwas vor sich wie die allerreifste Frucht, wie die wunderschönste Ausgestaltung einer langen Menschheitsentwickelung, die durch Jahrtausende herangewachsen ist und endlich einen reifen, weisen und künstlerischen Ausdruck gefunden hat in der herrlichen Gita. Und in den Paulusbriefen hat man vor sich den Keim von etwas völlig Neuem, das wachsen und immer mehr wachsen muß, und das man in seiner vollen Bedeutung nur auf sich wirken lassen kann, wenn man es eben als keimhaft betrachtet und wenn man wie prophetisch im Auge hat dasjenige, was einmal daraus werden soll, wenn Jahrtausende und aber Jahrtausende der Entwickelung verflossen sein werden in die Zukunft hinein, und reifer und immer reifer geworden sein wird das, was keimhaft in den Paulusbriefen angelegt ist.

Nur wenn man dieses berücksichtigt, vergleicht man richtig. Dann ist man sich aber auch klar darüber, dafl das, was einstmals groß sein soll, zunächst in unscheinbarer Gestalt aus den Tiefen des Christentums in den Paulusbriefen wie chaotisch einmal aus der Menschheitsseele hervorquellen mußte. So wird anders darstellen müssen derjenige, welcher die Bedeutung der Bhagavad Gita auf der einen Seite und die Bedeutung der Paulusbriefe auf der anderen Seite für die gesamte Menschheitsentwickelung der Erde im Auge hat, und anders derjenige, der nach den fertigen Werken in bezug auf Schönheit und Weisheit und innere Formvollendung beurteilen muß.

Wenn man aber einen Vergleich der beiden Weltanschauungen ziehen will, die da in der Bhagavad Gita und den Paulusbriefen zutage treten, dann muß man zunächst die Frage stellen: Um was handelt es sich denn eigentlich dabei? Es handelt sich darum, daß wir mit alledem, was wir zunächst von den in Betracht kommenden Weltanschauungen historisch übersehen können, es zu tun haben mit der Heranziehung des Ich in der Menschheitsentwickelung. Wenn man dieses Ich in der Menschheitsentwickelung verfolgt, so kann man sagen: In den vorchristlichen Zeiten war dieses Ich unselbständig, war noch wie in verborgenen Seelengründen wurzelnd, hatte es noch nicht zu der Möglichkeit gebracht, sich selbsteigen zu entwickeln.

Daß die Entwickelung mit selbsteigenem Charakter möglich wurde, das konnte ja nur dadurch geschehen, daß in dieses Ich hinein der Impuls geworfen wurde, den wir eben mit dem Namen Christus-Impuls bezeichnen. Das, was seit dem Mysterium von Golgatha in dem menschlichen Ich sein kann und was zum Ausdruck in den Worten des Paulus kommt: «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mim, das konnte vorher nicht in diesem Ich sein. Aber in den Zeiten, in denen man sich schon mit der Betrachtung dem Christus-Impuls nähert, in dem Jahrtausend vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha, bereitete sich dasjenige langsam vor, was dann geschehen sollte durch die Einfügung des Christus-Impulses in die menschliche Seele. Es bereitete sich namentlich in einer solchen Weise vor, wie sie uns in der Tat des Krishna ausgedrückt wird.

Das, was nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha der Mensch in sich selber als den Christus-Impuls zu suchen hatte, das er zu finden hatte im Sinne der Paulinischen Form: «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mir», das mußte er vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha nach außen suchen, das mußte er so suchen, als ob es ihm aus den Weltenweiten wie eine Offenbarung hereinkäme. Und je weiter wir im Zeitenlauf zurückgehen, desto glanzvoller, desto impulsiver war die äußere Offenbarung. Man kann also sagen: In den Zeiten vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha ist eine gewisse Offenbarung an die Menschheit vorhanden, eine Offenbarung an die Menschheit, die so geschieht, wie wenn der Sonnenschein von außen einen Gegenstand bestrahlt. Wie wenn das Licht von außen auf diesen Gegenstand fallt, so fiel das Licht der geistigen Sonne von außen auf die Seele des Menschen und überleuchtete sie.

Nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha können wir das, was in der Seele wirkt als Christus-Impuls, also als das geistige Sonnenlicht, so vergleichen, daß wir sagen: Es ist, wie wenn wir einen selbstleuchtenden Körper vor uns hätten, der sein Licht von innen ausstrahlt. Dann wird uns, wenn wir die Sache so betrachten, die Tatsache des Mysteriums von Golgatha zu einer bedeutsamen Grenze der Menschheitsentwickelung, dann wird uns dieses Mysterium von Golgatha zu einer Grenze. Wir können das ganze Verhältnis symbolisch darstellen.

Wenn uns dieser Kreis (links) die menschliche Seele bedeutet, so können wir sagen: Das Geisteslicht strahlt von allen Seiten von außen an diese menschliche Seele heran. Dann kommt das Mysterium von Golgatha, und nach ihm hat die Seele in sich selber den Christus-Impuls und strahlt aus sich heraus dasjenige, was in dem Christus-Impuls enthalten ist (rechts).

Wie ein Tropfen, der von allen Seiten bestrahlt wird und in dieser Bestrahlung erglänzt, so erscheint uns die Seele vor dem Christus-Impuls. Wie eine Flamme, die innerlich leuchtet und ihr Licht ausstrahlt, so erscheint uns die Seele nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha, wenn sie in die Lage gekommen ist, den Christus-Impuls aufzunehmen.

Wenn wir dies ins Auge fassen, dann können wir dieses ganze Verhältnis mit solchen Bezeichnungen ausdrücken, wie wir sie in der Sankhyaphilosophie kennengelernt haben. Wir können sagen: Wenn wir das geistige Auge auf eine solche Seele hinrichten, die von allen Seiten umstrahlt ist von dem Licht des Geistes vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha, dann erscheint uns dieses ganze Verhältnis des Geistes, der die Seele von allen Seiten bestrahlt, der daher, indem wir das ganze Verhältnis anblicken, in seiner Geistigkeit uns erstrahlt, nach der Sankhyaphilosophie-Bezeichnung, im Sattvazustand. Dagegen erscheint uns die Seele, nachdem sich das Mysterium von Golgatha vollzogen hatte, wenn wir sie von außen mit dem geistigen Auge gleichsam betrachten, so, als wenn in ihrem tieferen Inneren das Geisteslicht verborgen wäre und das, was seelenhaft ist, dieses Geisteslicht verberge. Wie umhüllt von Seelensubstanz erscheint uns das Geisteslicht, das im Christus-Impuls enthalten ist nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha.

Und erblicken wir denn nicht dieses Verhältnis bis in unsere Zeit, ja ganz besonders in unserer Zeit, in bezug auf alles das, was der Mensch äußerlich erlebt, bewahrheitet? Man versuche einmal heute, einen Menschen zu betrachten, das, womit er sich beschäftigen muß an äußerem Wissen, an äußerer Betätigung, und man versuche dagegenzustellen, wie verborgen im tiefsten Inneren, wie noch als ganz schwach leuchtendes Flämmchen der Christus-Impuls, umhüllt von dem übrigen Seeleninhalt, im Menschen waltet. Das ist gegen den vorchristlichen Zustand, welcher der Sattvazustand im Verhältnis des Geistes zur Seele ist, der Tamaszustand.

Was macht also das Mysterium von Golgatha, in diesem Sinne betrachtet, in der Evolution der Menschheit? Es verwandelt in bezug auf die Offenbarung des Geistes den Sattvazustand in den Tamaszustand. Die Menschheit rückt dabei vor; aber sie tut, man möchte sagen, einen tiefen Fall, nicht durch das Mysterium von Golgatha, sondern durch sich. Das Mysterium von Golgatha macht die Flamme immer mehr und mehr wachsen. Daß aber die Flamme nur als eine kleine Flamme in der Seele erscheint, nachdem vorher das gewaltige Licht von allen Seiten die Seele beschienen hat, das macht die fortschreitende, aber in die Finsternis immer mehr und mehr hinein sich senkende Menschennatur. Also nicht das Mysterium von Golgatha ist schuld an dem Tamaszustand der menschlichen Seele im Verhältnis zum Geist, sondern durch das Mysterium von Golgatha wird verursacht, daß aus dem Tamaszustand in ferner Zukunft wiederum ein Sattvazustand zustande kommt, der jetzt von innen heraus angefacht wird.

Zwischen dem Sattva- und dem Tamaszustand liegt der Rajaszustand im Sinne der Sankhyaphilosophie, und dieser Rajaszustand ist in bezug auf die Menschheitsentwickelung durch die Zeit charakterisiert, in die eben das Mysterium von Golgatha hineinfällt. Die Menschheit selber macht in bezug auf Geistesoffenbarung den Weg vom Licht in die Finsternis, vom Sattvazustand in den Tamaszustand durch gerade in den Jahrtausenden um das Mysterium von Golgatha herum. Wenn wir diese Evolution noch genauer ins Auge fassen wollen, dann können wir sagen, wenn wir die Zeit der Evolution der Menschheit durch die Linie a- b bezeichnen: In der Zeit bis etwa ins 8. oder 7. Jahrhundert vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha, da war alles in der menschlichen Kultur im Sattvazustand.

Dann begann das Zeitalter, in das das Mysterium von Golgatha hineintiel, und dann begann das Zeitalter — wir können sagen, etwa vom 15., 16. Jahrhundert nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha -, dann beginnt so recht deutlich das Tamaszeitalter. Aber es ist ein Übergang. Und wenn wir unsere gewohnten Bezeichnungen anwenden wollen, dann haben wir das erste Zeitalter, das gewissermaßen noch hineinfiel für gewisse Geistesoffenbarungen in den Sattvazustand, mit dem Zeitalter zusammenfallend, das wir das chaldäischägyptische nennen. Dasjenige, das im Rajaszustande ist, ist das griechisch-lateinische, und dasjenige, das im TTamaszustand ist, ist unser Zeitalter. Wir wissen auch, daß von den nachatlantischen Zuständen dieses charakterisierte chaldäisch-ägyptische Zeitalter das dritte ist, das griechisch-lateinische das vierte und das unsrige das fünfte. Es hatte also stattzufinden, man möchte sagen, nach dem Plan der Menschheitsentwickelung, von dem dritten in das vierte nachatlantische Zeitalter gleichsam die Abtötung der äußeren Offenbarung, die Vorbereitung der Menschheit für das Aufflammen des Christus-Impulses. Wie geschah diese aber in Realität?

Nun, wenn wir uns erklären wollen, wie die Geistesverhältnisse des Menschen anders waren in dem dritten Menschheitszeitalter, in dem chaldäisch-ägyptischen, gegenüber den folgenden Zeitaltern, so müssen wir sagen: In diesem dritten Zeitalter war für alle diese Länder, sowohl für Ägypten wie für Chaldäa, aber auch für Indien, für alle diese Gebiete der Menschheitsentwickelung war die Sache so, daß die Menschheit eben noch Reste alter hellseherischer Kraft hatte; das heißt, der Mensch sah die Umwelt nicht nur mit Hilfe seiner Sinne und des Verstandes, der an das Gehirn gebunden ist, sondern er sah die Umwelt noch mit den Organen seines Ätherleibes, wenigstens in gewissen Zuständen, die zwischen Schlafen und Wachen waren.

Wenn wir uns einen Menschen jenes Zeitalters vorstellen wollen, so dürfen wir das nicht anders, als daß wir durchaus sagen: Für jene Menschen war das Anschauen von Natur und Welt, wie wir es kennen, durch die Sinne und den Verstand, der an das Gehirn gebunden ist, nur einer von den Zuständen, die sie erlebten. Aber in diesen Zuständen bildeten sie sich noch kein Wissen, da schauten sie gleichsam die Dinge nur an, und ließen sie wirken nebeneinander im Raum und nacheinander in der Zeit. Wenn sie zu einem Wissen kommen wollten, diese Menschen, dann mußten sie in einen Zustand kommen, der bei ihnen nicht so wie in unserer Zeit künstlich, sondern natürlich, wie von selbst eintrat, wo ihre tieferliegenden Kräfte, die Kräfte ihres Ätherleibes in Wirksamkeit traten zur Erkenntnis. Und aus einer solchen Erkenntnis ging auch noch alles das hervor, was uns als das wunderbare Wissen der Sankhyaphilosophie erschienen ist; aus einer solchen Betrachtung ging auch alles das hervor — nur gehört es einer noch älteren Zeit an —, was uns in dem Vedawissen überliefert ist.

Da also verschaffte sich der Mensch seine Erkenntnis dadurch, daß er sich in einen anderen Zustand brachte oder in einen solchen sich versetzt fühlte. Der Mensch hatte sozusagen seinen Alltagszustand, wo er mit seinen Augen sah, mit seinen Ohren hörte, mit seinem gewöhnlichen Verstand die Dinge verfolgte. Aber dieses Sehen, dieses Hören, diesen Verstand verwendete er nur, um die äußeren praktischen Verrichtungen zu besorgen. Er wäre gar nicht darauf gekommen, diese Fähigkeit auch für Wissenschaft, für Erkenntnis zu verwenden. Für Wissenschaft, für Erkenntnis verwendete er das, was ihm in dem anderen Zustand erschien, wo er die tieferen Kräfte seines Wesens in Tätigkeit brachte.

Wir können uns also den Menschen für diese alten Zeiten so vorstellen, daß er sozusagen seinen Alltagsleib hatte und innernalb dieses Alltagsleibes seinen feineren geistigen, seinen Sonntagsleib, wenn ich diesen Vergleich gebrauchen darf. Mit dem Alltagsleib arbeitete er das Alltägliche aus, und mit dem Sonntagsleib, der nur aus dem Ätherleib gewoben war, da erkannte er, da bildete er seine Wissenschaft aus. Und für einen Menschen dieser alten Zeit war es so, daß der Vergleich berechtigt wäre, wenn man sagte: Dieser Mensch ist erstaunt, daß wir in unserer Zeit mit unserem Alltagsleib unsere Wissenschaft uns zimmern und gar nie unseren Sonntagsleib anziehen, wenn es darauf ankommt, von der Welt etwas zu wissen. Ja, wie war es denn nun für einen solchen Menschen im Erleben dieser ganzen Zustände? Im Erleben dieser ganzen Zustände war es so, daß der Mensch, wenn er in dem Erkennen durch seine tieferen Kräfte war, also in dem Erkennen, wo er sich zum Beispiel die Sankhyaphilosophie ausbildete, daß er dann nicht so fühlte, wie der heutige Mensch fühlt, der, wenn er Wissenschaft erwerben will, seinen Verstand anstrengen und mit seinem Kopfe denken muß. Da fühlte er sich, wenn er sich Wissen erwarb, wie in seinem Ätherleib, der aber allerdings am wenigsten ausgeprägt war in dem, was heute physischer Kopf ist, sondern der in den anderen Teilen mehr ausgeprägt war. Der Mensch dachte viel mehr mit den anderen Gliedern seines Ätherleibes. Der Ätherleib des Kopfes ist der schlechteste Teil. Der Mensch fühlte sozusagen, daß er mit seinem Ätherleibe dachte, daß er im Denken aus seinem physischen Leibe herausgehoben war. Aber er fühlte noch etwas in solchen Augenblicken der Wissensbildung, der Erkenntnisbildung: er fühlte, wie er eigentlich ein Ganzes mit der Erde war. Er hatte das Gefuhl, wenn er seinen Alltagsleib auszog und seinen Sonntagsleib anzog, als ob Kräfte durch sein ganzes Wesen gingen, wie wenn Kräfte durch unsere Beine und Füße gingen und diese Kräfte uns mit der Erde so verbänden, wie die Kräfte, die durch unsere Hände und Arme gehen, sich mit unserem Leib verbinden. Der Mensch fing an, als ein Glied der Erde sich zu fühlen. Auf der einen Seite fühlte er, daß er dachte und wußte in seinem Ätherleibe, und auf der anderen Seite, daß er nicht mehr der abgesonderte Mensch war, sondern eim Glied der Erde. Er fühlte sein Wesen in die Erde hineinwachsen. Also die ganze innere Art des Erlebens änderte sich um, wenn der Mensch seinen Sonntagsleib anzog und sich zur Erkenntnis anschicken konnte.

Was mußte dann geschehen, daß so recht dieses alte Zeitalter aufhörte, das dritte und das neue Zeitalter, das vierte, eintrat? Wenn wir begreifen wollen, was da geschehen mußte, dann tun wir gut, uns etwas in die alte Bezeichnungsweise hineinzufühlen.

Der Mensch, der in jenem alten Zeitalter das erlebte, was ich eben charakterisiert habe, sagte: In mir ist die Schlange regsam geworden. — Sein Wesen hatte sich hineinverlängert in die Erde. Seinen physischen Leib fühlte er nicht als das eigentlich Tätige. Er fühlte sich so, wie wenn er einen Schlangenfortsatz in die Erde hinein erstreckte und der Kopf das wäre, was herausragte aus der Erde. Und dieses Schlangenwesen, dieses fühlte er als das Denkende. Und aufzeichnen könnte man sein Wesen so, daß sein Ätherleib sich in die Erde hinein als Schlangenkörper verlängerte, und daß, während er als physischer Mensch außerhalb der Erde war, während des Erkennens und Wissens er in die Erde hineinragte und mit seinem Ätherleib dachte. Die Schlange ist in mir tätig, sagte er. So also hieß gewissermaßen Erkennen in den alten Zeiten: Ich bringe die Schlange in mir zur Tätigkeit; ich fühle mein Schlangenwesen.

Was mußte geschehen, damit die neue Zeit eintrat, damit das neue Erkennen kam? Es mußte nicht mehr möglich sein, daß es solche Augenblicke gab, wo der Mensch sein Wesen in die Erde hinein durch die Beine und Füße hindurch verlängert fühlte. Und außerdem mußte das Gefühl im Ätherleib ersterben und mußte übergehen auf den physischen Kopf. Stellen Sie sich dieses Gefühl des Übergangs von der alten Erkenntnis zur neuen richtig vor, so werden Sie finden, es ist ein guter Ausdruck für diesen Übergang, wenn man sagt: Man wird an den Füßen verwundet, aber man selber zertritt mit seinem eigenen Leibe der Schlange den Kopf - das heißt, es hört auf die Schlange mit ihrem Kopf das Denkorgan zu sein. Der physische Körper, namentlich das physische Gehirn tötet die Schlange, und die Schlange räacht sich dafür, indem sie einem das Gefühl der Zusammengehörigkeit mit der Erde entzieht: sie beißt einen in die Ferse.

In solchen Zeiten des Übergangs von einer Form des Menschheitserlebnisses zur anderen, da befindet sich gleichsam das, was hereinragt aus der alten Epoche, mit demjenigen, was da kommt in der neuen Zeit, in einem Kampfe; denn die Dinge sind ja noch nebeneinander. Der Vater ist auch noch da, wenn der Sohn schon lange lebt. Trotzdem ist der Sohn das, was vom Vater herstammt. Die Eigenschaften des vierten Zeitalters, des griechisch-lateinischen, waren da, aber es ragten noch bei Menschen und Völkern die Eigenschaften des dritten, des ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeitalters herein. Das geht in der Entwickelung selbstverständlich ineinander. Aber das, was so als ein neu Aufgehendes und Altherkommendes nebeneinander lebt, versteht sich nicht mehr gut. Das Alte versteht das Neue nicht. Das Neue muß sich gegen das Alte wehren, muß sein Leben gegenüber dem Alten behaupten. Das heißt, das Neue ist da, aber die Vorfahren, die ragen noch mit ihren Eigenschaften in ihren Nachkommen herein aus dem alten Zeitalter, die Vorfahren, die nicht das Neue mitgemacht haben. So können wir den Übergang vom dritten Menschheitszeitalter in das vierte charakterisieren.

Es mußte also ein Held da sein, möchte man sagen, ein Führer der Menschheit, der zuerst in bedeutsamer Weise diesen Prozeß des Tötens der Schlange, des Verwundet-Werdens durch die Schlange darstellt und der zugleich sich aufbaumen mußte gegen das, was ihm zwar verwandt ist, aber mit seinen Eigenschaften noch aus der alten Zeit in die neue hereinleuchtet. Die Menschheit muß so vorwärtskommen, daf das, was ganze Generationen erleben, zuerst einer in seiner starken Größe zu erleben hat.

Wer war der Held, der da tötete den Kopf der Schlange, der sich aufbaumte gegen das, was im dritten Weltenalter bedeutsam war? Wer war der, der die Menschheit aus der alten Sattvazeit in die neue Tamaszeit herausführte? Das war Krishna. Und wie könnte uns das deutlicher dargestellt werden, daß es dieser Krishna war, als durch die morgenländische Legende, in der Krishna als ein Sohn der Götter hingestellt wird, als ein Sohn des Mahadeva und der Devaki, der unter Wundern in die Welt tritt, das heißt so, daß er etwas Neues bringt; der - wenn ich in meinem Vergleich fortfahre — die Menschen dahin bringt, daß sie im Alltagsleibe Wissen suchen, und der den Sonntagsleib, das heißt die Schlange tötet; der sich wehren muß gegen das, was von seiner Verwandtschaft in die neue Zeit hereinragt.

Ein solcher ist etwas Neues, etwas Wunderbares. Daher erzählt die Legende, wie das Krishnakind schon bei der Geburt von Wundern umgeben war, und daß der Bruder der Mutter des Krishna, Kansa, nach dem Leben des Krishnakindes trachtete. Da haben wir das Hereinragen des Alten in dem Oheim des Krishnakindes, und der Krishna hat sich zu wehren, hat sich aufzulehnen, er, der das Neue zu bringen hat, das, was das dritte Zeitalter tötet, was die alten Verhältnisse vernichtet für die äußere Menschheitsevolution. Er hat sich zu wehren gegen Kansa, den Bewahrer des alten Sattvazeitalters. Und unter den bedeutsamsten Wundern, mit denen Krishna umgeben wird, erzählt die Legende, daß die mächtige Schlange Kali ihn umwand und daß es ihm gelang, der Schlange den Kopf zu zertreten, daß sie ihn aber an der Ferse verwundete. Hier haben wir etwas, was wir so bezeichnen können, daß die Legende unmittelbar einen okkulten Tatbestand widergibt. Das tun die Legenden. Nur darf man sich nicht auf eine äußere Erklärung einlassen, sondern muß die Legenden an der richtigen Stelle, im richtigen Zusammenhang des Erkennens aufgreifen, um sie da zum Verständnis zu bringen.

Krishna ist der Held des untergehenden dritten nachatlantischen Menschheitszeitalters. Die Legende erzählt uns wiederum: Krishna trat am Ende des dritten Weltalters auf. Alles stimmt, wenn es verstanden wird. Krishna ist also derjenige, der das alte Erkennen tötet, der es zur Verfinsterung bringt. In seinen äußeren Erscheinungen tut er das. Er bringt zur Verfinsterung, was früher den Menschen umgeben hat wie eine Sattvaerkenntnis. Ja, wie steht er aber in der Bhagavad Gita da? So steht er da, daß er dem Einzelnen, gleichsam als einen Ausgleich gegen das, was er genommen hat, die Anleitung gibt, wie er wiederum hinaufkommen kann durch Yoga zu dem, was für das normale Menschentum verloren war.

So ist Krishna für die Welt der Töter der alten Sattvaerkenntnis und zugleich, wie er uns am Ende der Gita entgegentritt, der Herr des Yoga, der wiederum in die Erkenntnis hinaufführen soll, die man verlassen hat, in die Erkenntnis der alten Zeiten, die man nur erlangen kann, wenn man das, was man jetzt äußerlich wie ein Alltagskleid angezogen hat, überwindet und besiegt, wenn man zu dem alten Geisteszustand wiederum zurückkehrt. Das war die Doppeltat des Krishna. Als welthistorischer Held hat er auf der einen Seite gehandelt, indem er der Schlange der alten Erkenntnis den Kopf zerbrochen hat und die Menschheit zur Einkehr in den physischen Leib gezwungen hat, in dem allein das Ich erobert werden konnte als freies, selbsttätiges Ich, während früher alles das, was den Menschen zum Ich machte, von außen hereinstrahlte. Das war er als welthistorischer Held. Dann war er für den Einzelnen derjenige, der für die Zeiten der Andacht, der Versenkung, für das innere Finden wiedergab, was einstmals verloren war. Und das ist es, was uns in so grandioser Weise in der Szene der Gita entgegentrat, die wir gestern am Schluß auf unsere Seele wirken ließen, und was dem Arjuna entgegentritt als das eigene Wesen, aber außen gesehen, gesehen so, daß es anfang- und endlos über alle Raume verbreitet ist.

Und wenn wir dieses Verhältnis genauer noch beobachten, dann kommen wir an eine Stelle der Gita, die, wenn wir sonst schon verwundert sind über den großen gewaltigen Inhalt der Gita, diese unsere Verwunderung noch ins Unbegrenzte vergrößern muß. Da kommen wir an jene Stelle, die allerdings für den heutigen Menschen recht unerklärlich sein muß, an jene Stelle, wo der Krishna dem Arjuna offenbart, welches die Natur des Ashvatthabaumes ist, des Feigenbaumes, indem er ihm sagt, daß dieser Baum wurzelaufwärts und zweigabwärts gerichtet ist, und wo Krishna weiter sagt, daß die einzelnen Blätter dieses Baumes die Blätter des Vedabuches sind, die zusammen das Vedawissen geben. Das ist eine eigentümliche Stelle. Was heißt denn diese Stelle, dieser Hinweis auf den großen Baum des Lebens, dessen Wurzeln nach aufwärts und dessen Zweige nach abwärts gerichtet sind, dessen Blätter den Inhalt des Veda geben?

Ja, da müssen wir uns eben in die alte Erkenntnis versetzen und uns klarmachen, wie die alte Erkenntnis wirkte. Der gegenwärtige Mensch kennt ja nur sozusagen seine heutige Erkenntnis, die ihm vermittelt wird durch das physische Organ. Die alte Erkenntnis wurde errungen, wie wir gerade dargestellt haben, in dem noch ätherischen Leib. Nicht, daß der ganze Mensch ätherisch gewesen wäre, sondern es wurde die Erkenntnis errungen im ätherischen Leib, der im physischen Leibe war. Durch die Organisation, durch die Gliederung des ätherischen Leibes wurde die alte Erkenntnis erworben.

Stellen Sie sich das einmal lebendig vor: Wenn Sie im ätherischen Leib, mit der Schlange erkennen, da ist etwas in der Welt vorhanden, was für den heutigen Menschen nicht in der Welt ist. Nicht wahr, der heutige Mensch nimmt ja vieles wahr in seiner Umgebung, wenn er sich naturgemäß verhält. Aber stellen Sie sich einmal den Menschen vor, die Welt betrachtend: eines nimmt der betrachtende Mensch nicht wahr, das Gehirn. Das eigene Gehirn kann kein Mensch sehen, wenn er beobachtet. Kein Mensch kann auch sein eigenes Rückenmark sehen. Diese Unmöglichkeit hört auf, sobald man im Ätherleib betrachtet. Da tritt ein neues Objekt auf, das man sonst nicht sieht: das eigene Nervensystem nimmt man wahr. Aber man nimmt es allerdings nicht etwa so wahr, wie es der heutige Anatom wahrnimmt. So schaut es nicht aus, wie er es wahrnimmt, sondern es sieht so aus, daß man das Gefühl bekommt: Ja, da bist du in deiner Äthernatur! - Jetzt schaut man nach aufwärts und sieht, wie sich die Nerven, die in alle Organe gehen, nach oben im Gehirn zusammensammeln. Das gibt das Gefühl: Das ist ein Baum, der nach oben seine Wurzeln hat, nach aufwärtsgehend, und der seine Zweige in alle Glieder hinunterstreckt.