Speech and Drama

GA 282

12 September 1924, Dornach

VIII. The Moulding and Sculpting of Speech

We will begin today with a recitation given by Frau Dr. Steiner, which will, I think, bring home to you with added force all that we have been considering in the last lectures. For the scene that will be read provides excellent opportunity for showing how one who seriously wants to be an artist in his work on the stage can find the way to a right forming of his speech.

Whether or no we attain to this depends in great measure upon our ability to effect a certain inner adaptation of our speaking so that it may truly have the qualities both of sculpture and of painting. We shall very likely have some ,,trouble in getting rid of what might well be called the greyness of speech that is only too common on the stage today. I mean the speech that is content to remain at the prosaic level of the speaking we use in everyday life. We shall really have to bestir ourselves to effect a reform in this direction, for this latest phase in the development of acting is taking us farther and farther away from art. It seems indeed to be the aim and object of the modern actor to speak without any art at all, employing as he does for the stage merely the speaking of ordinary everyday intercourse.

Judged from the standpoint of naturalism, the acting profession of the present day has undoubtedly succeeded in achieving a very high standard; the achievement, however, has nothing artistic about it.

On many occasions during recent years I have been utterly amazed at the naturalistic performances I have witnessed on the stage. Again and again one has been confronted with the strange phenomenon of a play being acted without the least attempt to develop a style that could lift the performance to the level of art; one has had, on the contrary, the feeling of being transported into a stark realism of the most everyday description. Needless to say, we do not go to the theatre for that!

Anyone who looks for nothing else but sheer naturalism in an artistic performance is like a person who doesn't care for a portrait painted by an artist; that doesn't please him at all, he would much rather have a photograph, preferably perhaps a coloured one, since he can understand that more readily. But the whole secret of art lies in this: in art we reveal truth by quite other means than Nature uses. Nature reveals truth more immediately. Truth must be present in Nature; and truth must be present also in art. The truth in Nature shines forth to the spirit : from the truth in art the spirit shines forth. Once we have grasped this fact and made it our own, we shall feel within us an urgent need to discover how art and style can be restored to the stage, and we shall not rest until we find it. I will tell you of something that can prove helpful in this connection.

Practise bringing your speech organs into a kind of speaking the very nature and quality of which oblige you to diverge from the naturalistic speaking of everyday intercourse. You will have an example of this in the scene to which we shall presently be listening. The scene is taken from Lessing's play Minna von Barnhelm, in which one of the characters, Riccaut de la Marlinière, is a Frenchman speaking German. It is impossible to speak this part in an ordinary everyday manner; one has perforce to give a certain style to the speaking of Riccaut de la Marlinière. He is constantly interposing French words and phrases, and his German has always a French accent. Such a part could well be used as an exercise in the forming of speech; it will help the student to acquire a fluency that has style. This was indeed our reason for choosing the scene.

(Frau Dr. Steiner): The scene is laid in a room in an hotel. Riccaut de la Marlinière enters expecting to find there Major Tellheim.

RICCAUT. (within) May I come in, Major?

FRANZISKA. What is it? Does somebody want us? (Going towards the door.)

RICCAUT. Good heavens, I've made a mistake! But no, I haven't—this is certainly his room.

FRANZISKA. This gentleman, Mademoiselle, is evidently expecting to find Major von Teilheim.

RICCAUT. Exactly so! Major von Tellheim; yes, my dear, he is the man I am looking for. Where is he?

FRANZISKA. He is not living here any longer.

RICCAUT. What? Twenty-four hours ago he was living here, and you say that now he is not? Where is he then?

MINNA. (coming forward) Sir—

RICCAUT. Ah, Madame—Mademoiselle—pardon me!—

MINNA. My dear sir, your mistake is entirely excusable and your surprise very natural. The Major has been so kind as to give up his room to me—a perfect stranger, who was at a loss where to find a lodging.

RICCAUT. Ah, that is just like him—always so polite! Such a gentleman, our Major!

MINNA. But where he has removed to—really, I'm ashamed to say, I do not know.

RICCAUT. Mademoiselle does not know? That's a pity; I am distressed to hear it.

MINNA. I ought of course to have inquired. His friends will certainly be expecting to find him here.

RICCAUT. I am one of his best friends, Mademoiselle.

MINNA. Franziska, don't you know his present address?

FRANZISKA. No, I do not, Mademoiselle.

RICCAUT. I have something very important to communicate to him. I am the bearer of news that he will be delighted to receive.

MINNA. I am the more sorry. I do, however, hope to have opportunity myself to speak with him-perhaps quite soon. If it does not matter from whose lips the Major learns the good news, may I offer myself, Sir?

RICCAUT. I understand. Mademoiselle speaks French? But of course; I can see that without asking. It was most rude of me to put the question. Pardon me, Mademoiselle!

MINNA. My dear sir?

RICCAUT. Really not? Mademoiselle does not speak French?

MINNA. In France, Sir, I would try my best to speak it. But why should I here? I can see that you understand me. And I shall most certainly also understand you-so speak French or German, whichever you please.

RICCAUT. Good! And I also am quite able to make myself understood in German. This then is my news, Mademoiselle. I have just been lunching with the Minister-the Minister of -what is he called, the Minister who lives over there in that long street? by the big square?

MINNA. I am still quite a stranger here.

RICCAUT. I know, the Minister of War. -I had luncheon with him-I generally do eat at his table. The conversation turned on Major Tellheim; and the Minister told me in confidence-for His Excellency is a friend of mine and we have no secrets from one another-His Excellency confided to me that the affair with our Major is on the point of being wound up, and to a happy conclusion. His Excellency has given in his report to the King, and the King has made his decision on it entirely in the Major's favour.- ‘Monsieur,’ he said to me, ‘you understand, I am sure, how everything depends upon the way in which matters are represented to the King-and you know me. He's a thoroughly nice fellow, this Tellheim, and I know very well that you have an affection for him. The friends of my friends are my friends too. He's rather a heavy expense to the King, you must know, but does one serve kings for nothing? We must help one another in this world; and if there must be losses, then the King has to be the person who bears them and not some one of us honest fellows. This is my principle, and I never depart from it.’—What does Mademoiselle say to that? A good man, isn't he? Oh, His Excellency has his heart in the right place. He has moreover assured me that if the Major has not already received a letter in the King's own handwriting, he will without fail do so today.

MINNA. This news, my dear sir, will assuredly be most welcome to Major von Tellheim. I would only like to be able at the same time to tell him the name of the friend who takes such a warm interest in his good fortune.

RICCAUT. Mademoiselle wishes to know my name 9 You see in me the Chevalier Riccaut de la Marlinière, Seigneur de Prêt-au-val, de la branche de Prensd'or.-Mademoiselle is astonished to hear that I come from so great and noble a family-a family that positively has royal blood in its veins. Added to that, I am, without a doubt, the most adventurous cadet that our house has ever had. I have been in the service ever since I was ten years old. An affaire d'honneur obliged me to desert. Then I took service under His Holiness the Pope, and successively under the Republic of San Marino, the Polish Crown, and the States-General, until finally I came here. Ah, Mademoiselle, how I wish I had never seen this country! Had it but been granted to me to remain in the service of the States-General, I would by now most certainly have been Colonel at the very least. But to stay here for ever as Captain, and retired Captain at that—

MINNA. Bad luck indeed!

RICCAUT. Yes, Mademoiselle, that is my plight-discharged, and by that means thrown right out of employment!

MINNA. I am so Sorry.

RICCAUT. You are very kind, Mademoiselle. No, there is no recognition of merit here. To put a man like me on half- pay! A man, too, who has ruined himself in the service. I have spent in it more than twenty thousand pounds. And what have I now? To be quite candid with you, I haven't a sou left, I stand before you literally reduced to utmost poverty.

MINNA. I am most concerned to hear it.

RICCAUT. You are very kind, Mademoiselle. And now- you know the old saying, that every stroke of bad luck draws another after it; and it has been so with me. For what resource is left to a man of honour, of my birth and parentage, except gambling? So long as I was not in need of good luck, good luck always attended my play. But now that I need it badly, you would never believe how luck goes against me. Fifteen days have gone by, and on every single one of them I have lost. Yesterday again I lost heavily three times over. I know very well there are other things that count besides play. For among those with whom I play are certain ladies- I will say no more. One must be gallant to ladies. They have also invited me to come again today and play them a return game; but-you will understand me, Mademoiselle, when I say that one must first be sure of something to live on, before one can have money to play with.

MINNA. I hardly dare to hope, my dear sir—

RICCAUT. You are very kind, Mademoiselle—

MINNA. (taking Franziska aside) Franziska, I am really downright sorry for this man. Do you think he would take it amiss if I were to offer him something?

FRANZISKA. He doesn't look to me as if he would.

MINNA. All right, then!-I understand, Sir, that you play for money, and doubtless in places where there is something to gain. I must confess to you that I also am very fond of play?

RICCAUT. That's right, Mademoiselle, I am delighted to hear it! All people of intelligence love play to distraction.

MINNA.—and that I do specially like to win, and am only too happy to venture my money with a man who-well, who really knows how to play. Would you perhaps be inclined, Sir, to take me into partnership? to allow me a share in your bank

RICCAUT. What is that, Mademoiselle? You would like to go halves with me? With all my heart.

MINNA. I would like to begin with quite a small amount—(She goes to fetch money from her purse.)

RICCAUT. Oh, Mademoiselle, this is most charming of you-

MINNA. Here is some money that I won not long ago- a mere ten pistoles! I really feel a little ashamed to offer so small a sum?

RICCAUT. Hand it over, Mademoiselle, hand it over! (He takes the money.)

MINNA. I presume that your bank, Sir, is one of good standing—

RICCAUT. Oh, most certainly, highly respectable. Ten pistoles? Mademoiselle shall have for that a share in my bank amounting to a third. For a whole third the sum should of course be—a little bigger. But with lovely ladies one must not be too precise. I congratulate myself on having made the acquaintance of Mademoiselle, and from this moment I begin to have sure hopes that my luck will turn.

MINNA. But I cannot be present when you play.

RICCAUT. What need for that? We other players are people of strict honour amongst ourselves.

MINNA. If we have good luck, Sir, you will bring me my share. But if we are unlucky—

RICCAUT. Why, then, Mademoiselle, I will come to you for reinforcements.

MINNA. Reinforcements might well fail in the long run; so please protect our money carefully, Sir.

RICCAUT. What does Mademoiselle take me for? A simpleton? A stupid idiot?

MINNA. Pardon me—

RICCAUT. Je suis des Bons, Mademoiselle. Do you know what that means? I am an old hand at play.

MINNA. But yet I suppose, Sir?

RICCAUT. I know how to set a trap—

MINNA. (in astonishment) But you surely can't possibly do that?—

RICCAUT. I cunningly slip the card—

MINNA. Never!

RICCAUT. I cut cleverly so as to turn up the card I want—

MINNA. But you won't, will you, Sir?

RICCAUT. And why ever not, Mademoiselle? Give me an innocent young pigeon to pluck, and—

MINNA. Play false? Cheat?

RICCAUT. What is that you say, Mademoiselle? You call that ‘cheating’? To compensate oneself for bad luck, and make sure of success-do Germans call that ‘cheating’? Cheating indeed! What a poverty-stricken language, what a vulgar language, German is!

MINNA. No, Sir; if you really take that view?

RICCAUT. Leave it all to me, Mademoiselle, and don't disturb yourself. What does it matter to you how I play? Enough! tomorrow Mademoiselle will either see me again with a hundred pistoles, or will not see me again at all- Your most humble servant—(He hurries away.)

MINNA. (looking after him with surprise and vexation) I sincerely hope, Sir, the latter!

(Dr. Steiner): And now let us ask ourselves: why do we need speech formation as a special art on its own, within the realm of drama?

Suppose you are taking part in a scene where you are engaged in conversation with another actor, and you stand there listening to him in just the same way as you would in real life. No one could call that art. In ordinary conversation we hear the other person's words, but pay hardly any attention at all to the sound of the words or the intonation; we do not stop to appreciate the forming of the speech. In fact, we hear as little of the forming of word or of speech as we see of a transparent pane of glass. We look through the glass to what is behind; and in ordinary life we look through -or rather, hear through-the word. The word has become for us trans-audible; we scarcely notice the word itself and the way it is formed. And this is what we must learn to do again. A serious effort must now be made to restore to the art of the stage the hearing of the word. We must not be content merely with looking through the word as one looks at trees through a pane of glass, looking through the word in order to see what the other person means, trying to catch his thought or his feeling, or some news he is telling us. We must learn to hear the word itself, and experience a real content in this hearing of the word. Thought is, in a way, the death of art; the moment something real that is seeking artistic revelation passes into the realm of thought, art has left it. What art would show forth to us, we must hear, we must see.

But now, the art of the stage is concerned with human beings—with human beings who think and feel. A dramatic performance has to portray human beings; that is its concern. When, however, we form our words so that this formed word manifests itself as having an artistic value of its own, something of the human being is lost in the process. This has to be made up for; and the only way to do it is by mime and gesture.

Here, you see, we have reached the moment of transition from the arts of recitation and declamation to the art of acting as such, and this is where we come up against the necessity for a specific and thorough training for the stage.

Once again we can do no more at the moment than put forward a kind of ideal for such a schooling, in so far as mime, gesture and so on are concerned; for, conditions being as they are today, it can be only in the rather distant future that students of dramatic art will be able to receive a training that approaches it. The very cherishing of an ideal, however, the very setting out together in this way to consider what has eventually to be achieved, will help you to go forth in quest of that ideal, and to travel as far on the road as the limitations of the present time allow.

Let us then put the question: What should a school of dramatic art be like? What form should it take? And here, right at the beginning, let me say a word that will, I hope, remove some misunderstandings. In a school of dramatic art, just because it has to do with living men and women who have their own individual forms of expression, it has necessarily to be a question of educating by means of examples, giving the students indications and directions, but always in such a way that these are understood to be examples,-single instances out of many. For in everything to do with the stage the freedom of the artist has to be most strictly respected. It will therefore not be a matter of providing students with instructions that have to be followed with a pedantic adherence to the letter; advice will be given of a good way in which this or that can be done, and then the students will be left free to form and develop their work in the spirit of the given indications. And this is how I mean you to take the description I shall now give of what should be a first step in preparation for speaking on the stage.

At the beginning of this course of lectures I drew your attention to the gymnastics of the Greeks, showing you how these were developed instinctively from the organism of man. For the five main activities of Running, Leaping, Wrestling, Discus-throwing, Spear-throwing, do actually present in a kind of ascending scale activities that the nature of man may be said to require.

In order to meet the needs of modern times there will obviously have to be some modification of the old forms. Nevertheless, we shall get a pretty good idea of how our gymnastic movements should be today if we study these five main activities, thinking of them as ensouled by the spirit. For so we may truly describe the gymnastics of ancient Greece; they were ensouled by the spirit—they had something of genius about them, and those who practised them came under an influence that was genuinely artistic, genuinely spiritual. We have not time now to consider the modifications that might have to be introduced; I think, however, you will grasp the essential point if, in making the following suggestions for training, I simply use the terms that belong to the gymnastics of ancient Greece.

This then is how a training for the stage should begin—with a course of training in gymnastics, given in the spirit of the gymnastics of ancient Greece. The five main exercises, somewhat recast for the present age, should be well and thoroughly practised: Running, Leaping, Wrestling, Throwing the Discus (or some similar object), Throwing the Spear (or some similar object). Why do I recommend this course

in gymnastics? Not in order that the actor may acquire skill in this direction; I have no desire to make an athlete of him. The art of acting, let me tell you, will never attain its true nobility if it is allowed to go the way of Reinhardt2Max Reinhardt (1873–1943) was for many years a popular producer in Berlin (where he founded in 1905 a school of dramatic art) and afterwards in Vienna. His influence was all for naturalism, and he gave rauch more attention to scenic effects than to the cultivation of good speaking. and suffer methods of the circus to be brought in; rather must it free itself entirely from any such connection and go steadily forward in pursuit of its proper aim,- namely, the worthy rendering on the stage of the poetry and art that are inherent in true drama. When we say that a training for the stage should begin with gymnastics, we have something altogether different in mind. We are thinking of the need for the forming of the word to become in the actor a complete matter of course, so that it takes place in him instinctively; and the gymnastics can give just the right help to bring this about. Mime and gesture too—these above all have to become a matter of instinct. They must of course avoid being naturalistic, they must have art, they must have style, they must be as though impelled straight from the world of the spirit; and yet they have to become for the actor as spontaneous and unpremeditated as the behaviour of ordinary persons in everyday life—of persons, that is, who are not affected, and do not give themselves airs. With the same natural spontaneity that belongs to everyday life must the actor be continually giving artistic form to his words, his gestures, his physiognomy.And so, while pursuing his conscious study of the art, the actor should at the same time be experiencing it instinctively; he has to be able to combine the two; while learning it, he must also live it,-otherwise his words and gestures will constantly give the impression of being artificial.

And now, let us say, you learn Running. Then you will be learning how to walk on the stage—that is to say, your walking will give the right articulation to the word.

Running: Walking, so as to give the right articulation to the word.

The spectator has, you see, to understand from gesture and mime what he is not able to receive through his hearing. What the actor speaks, we are to hear. What the actor does—his mime and gesture-that, out of a certain instinct, we are to understand. There, understanding is in place, since there art can enter in; for in ordinary life we do not use mime and gesture,--not, at all events, with conscious intent.

By the exercise of Leaping, we learn how to modify our walking on the stage; one part of the text will require slow walking, while with another we shall want to walk more rapidly. We learn, in fact, to adapt our walking instinctively to the various ways of speaking which I described in an earlier lecture, showing you how the word can be incisive, full-toned, or long drawn out, can be abrupt or hard or gentle. Each of these qualities in speaking has to be accompanied by a corresponding modification of walking. On the stage, neither speaker nor listener may walk in an arbitrary manner. The pace has to be learned from the word; according as the word is incisive or full, deliberate, hard or gentle, so must we learn to bring our walking into the right measure, moving now more quickly, now more slowly, reaching even at times that utmost slowness that consists in standing still. And this we acquire instinctively when we practise Leaping.

Leaping: The adaptation of walking to the character of the spoken word.

We touch here a secret of human nature,-in so far as human nature may be allowed to have a say in the art of the drama. That the adaptation of walking to the character of the word is instinctively acquired through the exercise of Leaping is not a thing one can prove by argument, but only by experience. Put it into practice, and you will find that it is so. There are, I can assure you, many things in life that can only be learned by trying them out, and all the theories people build up concerning them are worth nothing at all.

In the exercise of Wrestling one learns how to move one's hands and arms when speaking,-again instinctively. This is best learnt from Wrestling.

Wrestling: Hand and arm movements.

In the Throwing of the Discus, where man has to let his gaze follow the direction of the throw, follow the whole path taken by the discus after it is thrown, his look changing, adapting itself to correspond, adapting itself even to the movement of the hand—in Discus-throwing, paradoxical as it may sound, we learn play of countenance. A play of countenance that comes and goes without effort, implying full control of the facial muscles—this is what can be learned from Throwing the Discus. It can as well be the throwing of a ball, or other similar object; I use, however, the Greek term for the exercise.

Discus-throwing : Play of countenance.

Lastly we come to what may well seem strangest of all. And this again can naturally never be proved by argument, it has to be experienced.

By practising Throwing the Spear, one learns to speak. Sticks can quite well be used instead of spears, but it must be exercise in this kind of throwing. For, as we practise Spear-throwing, our speech acquires the immediate effectiveness that enables it to work as speech, and not as an expression of thought. So, you see, the actor actually requires for his training that he should exercise himself in throwing things like sticks and spears! The alertness and care that are needed for it will draw the speaking away from the intellect, and take it right into the speech organs, allowing it to mould and form them. Spear-throwing is nothing less than the foundation for speech.

Spear-throwing: Speech.

I mean that of course in the broadest sense. Then will follow the specific speech exercises which we went through earlier on. But if we are envisaging a properly ordered school for dramatic art, we should ensure that our students discover from their own experience that the throwing of long spear-like objects evokes in them an instinctive understanding for what has been given in these lectures in reference to the forming of speech. If all of you sitting here had for a long time been practising Spear-throwing, you would be in no doubt at all about the truth of my words. Things of this kind do not admit of theoretical proof; they prove themselves in the doing. The results of such a training will soon show in those who undertake it. Spear-throwing provides the exactly right occult training for one who would attain proficiency in stage speaking.

So now you can form for yourselves a picture of what the beginners' class in a school for dramatic art should be like. And when, working out of the spirit of the whole, we come to consider the individual student, the human personality who stands before us as the subject of the art, and begin to study with him all the further details, we shall not communicate these in a dogmatic way as if they were rules, but rather as suggestions. All instruction for the stage must in fact be, as we said before, by way of suggestion and advice. In regard to what he has learned, the would-be actor has to be left absolutely free; he may carry it out precisely as it has been given him, or on the other hand he may, working out of the same spirit, do it differently.

One of the very first things a student has to learn is that not for a single moment should there be on the stage an unoccupied actor. No one must ever stand on the stage, doing nothing. It is distinctly a fault if a moment occurs in a play when one actor is talking, and a few others, whose presence the scene requires, are simply standing about, doing nothing at all. The one who is doing the talking—he is talking; the others who are listening must every one of them be participating all the time in what he is saying. Suppose there are four actors on the stage and one is speaking; then the other three should also be acting, they have to play with the speaker, playing in mime and in gesture. This is where the art of production comes in. The producer is responsible for the picture that the stage presents throughout the play, and he must make sure that there is never on the stage an actor who is unoccupied.

If an actor were to stand on the stage and listen just as in real life, instead of acting the listening, that would be an artistic fault. Listening on the stage with full inner experience must not be a real listening, it must not be naturalistic, it must be an acted listening. Along with everything else, it has to be drawn into the stream of the acting. And so the listening actor has to try to find at every turn a gesture that can rightly accompany the formed speech of the speaker. Naturalism on the stage has the same effect as marionettes.

If we have the impression (as we very often have had in recent times) that the people up there on the stage are successfully evoking the illusion of naturalistic reality, then, judged from an artistic standpoint, they are no more than marionettes—the very antithesis of dramatic art. What is needed is that we should develop an inner perception for certain relationships of mime and gesture to the content of the spoken word.

Suppose an actor has something intimate to communicate. The spectator must feel this; he must be able to know at once that information of an intimate nature is being given. He will not feel it if the actor walks backwards as he speaks; he will, however, if the actor places himself on the stage so that he can go forwards while he is speaking. Whenever you want to suggest intimacy, always move forwards, going from the back of the stage in the direction of the footlights.

Technical details of this nature are often neglected on quite absurd grounds. I once knew a talented actor whose work on the stage reached a high standard in many respects, but who would not learn his part. He simply did not want to take the trouble! The consequence was, he was a continual source of annoyance to the poor producer, for he would say to the other actors: ‘As for you, boys, you can move about the stage or stand just where you like; I am going to plant myself here’; and ‘here’ was close by the prompter's box. And there he remained all through the play. In other respects he was an excellent actor. It is, you see, a matter of actually living all the time in the artistic; we must never forget to be artists.

Suppose I have before me a little group of people to whom I am telling something, not now of an intimate nature, but merely by way of information. The spectator must be made to feel that the information is of interest to the others who are listening. How the latter should comport themselves, with that we will deal later; for the moment we are concerned with the speaker. If I want the spectator to have the impression that the group of persons to whom I am giving the information are taking it all in, I shall have to move slowly backwards within the group. The spectator, seeing this in perspective from his seat in the auditorium, will then feel that the listeners are following me with full understanding. Were I instead to walk straight through my group of listeners in the direction of the audience, the latter would receive the impression that my speaking goes past the listeners completely, that they simply do not understand it. Details of this kind belong to the inner technique of the stage. They are the elements from which we have to form the continually changing picture of the stage.

If one drops into one of our modern theatres to see a play, as often as not it doesn't seem to get anywhere. For this is the sort of thing that is constantly happening. First, one actor will light a cigarette and puff away, then another will do the same—and so it goes on. This lighting of cigarettes is cultivated as an art; actors acquire a special dexterity in it.

I have even observed that people rather like a scene that opens somewhat as follows. An actor comes on the stage and for quite a long time says nothing at all, lets the ` word ' retire altogether into the background. He sits down, and slowly pulls off one of his boots. He wants to show us in realistic manner that he has come home rather late. Then he puts on a slipper. All this time he has not spoken a single word. He pulls off the other boot and puts on the other slipper, still without speaking a single word. Then he proceeds to take off his coat, walks meanwhile a few steps across the room, as anyone might naturally do, and puts on his dressing gown. Next, he goes over to the corner of the room and lights the fire; he doesn't want to be cold. And never yet one word! And so he continues with his preparations for bed. Many different things may take place, of course, between taking off one's boots and turning in; but in order to carry out whatever little play of mime or gesture is involved in all this, what, after all, does the actor require? Certainly no serious study! He will have to be confident that he knows how people behave when they are at home; and then in addition he will need a little audacity to display himself doing such commonplace things. That is positively all he will need.

A method of this kind can obviously never lead to the development of art on the stage. Under certain conditions it can have disastrous consequences. If the actors happen never in their lives to have seen what they are supposed to portray, then the result on the stage can be frightful. I recently witnessed a performance where one of the scenes was played at court, and it was only too evident that none of the cast had ever seen a court.

We must look such things in the face; to do so will help to give us a true feeling for how things should be done if they are to be done artistically. And you will find that the dramatist and the actor, when both are truly artistic, will agree on this matter.

Look at Goethe's best plays. You will not find in them many stage directions; actually, as few as ever possible! Turn up Tasso or Iphigenie. The actor is left free. And that is right; he needs his freedom. There was a time in Goethe's life when he was in contact with some very good actors, and he learned a great deal from them—helped of course by his own powerful artistic urge. Once when Goethe was beginning, quite in the modern style, to give the actress Coronna Schröter some detailed instructions for her part, she is said to have replied: ‘What you say, sir, is all very well; but it won't do, you know! I shall play the part in the way that suits me!’

And now look, on the other hand, at the stage instructions that you find in modern playwrights, sometimes whole pages of them. It is a perfect misery to have to wade through them. In fact, no sensible person will trouble to do so. He wants it left to him to supply these details out of his own imagination, as he reads the play.

Yes, we have many such plays today, with their prolonged stage instructions and here and there a page of text in between. You have but to compare them with Tasso or with Iphigenie to see at once that the art of play-writing has suffered a decline, no less than the art of the stage.

Everything the actor has to do must be done instinctively. If he is doing it in obedience to a strict injunction, it will look artificial, it will look studied. You must, however, realise how very much can find its way into the actor's instinct, can become instinctive in him.

Think that you have before you the stage and the auditorium. The spectator is sitting there, and he has two eyes. If he had not these two eyes, then all the mime and gesturing of the actor would go for nothing. But now these two eyes are not just dead things about which we need not concern ourselves, they are alive. And a great deal of what happens on the stage, if it is to be rightly received, must take account of these two eyes.

For the remarkable thing is that our eyes are not alike in the way they receive what comes into their field of vision. ; We are not of course generally aware of this in ordinary life, nor is the science that belongs to our age; nevertheless, it is so, our two eyes are not alike The right eye is more competent for understanding what is seen, whereas the left is adapted rather to taking an interest in the object at which we are looking.

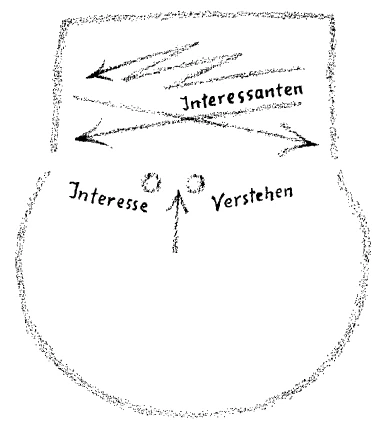

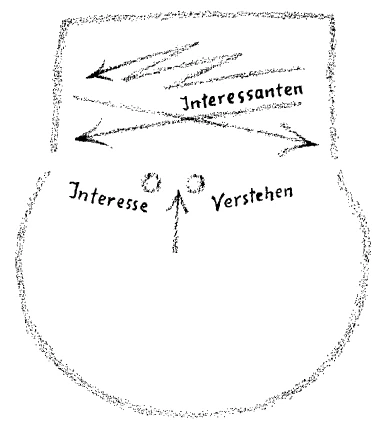

So this is the way we must think of the spectator as he sits facing the stage:

Say you are taking part in a play and have come to a passage where it is particularly important-and your own artistic feeling should tell you so-to succeed in arousing the spectator's interest. You will then need to walk, as actor, from left to right. This will mean that the eye of the spectator, as it follows you going (for him) in this direction ↙, will receive the impression of something that is interesting to him. If the passage in question is rather long, the actor will find it a good plan to go also backwards; the interest can quite well weaken a little without hurt. (See drawing.)

This is simply a technique of the stage to meet the requirements of the eyes.

But now suppose I have a passage where there is not the same call to stimulate the interest and feelings of the spectator, but where I want to appeal directly to his understanding, where I want perhaps to discuss or argue—as may often happen in a play. In this case, I shall have to move in the opposite direction for him ↘—that is to say, as seen from the stage, I shall have to go from right to left.

These are things that need to be known. An actor should know how disturbing it is for the spectator, if when the words he speaks are intended to awaken interest, he moves in this direction: ↘ (as seen from the audience); it will mean that no interest will be awakened in the spectator. His interest will, however, be awakened when the actor goes, for his view, in this direction: ↙ These things simply are so. And they have to be felt, they have to be experienced, like everything else in art.

If we are once able to look with this kind of insight upon all the details of stage management, then we can work in perfect freedom—working out of the spirit—at the arrangement of our scenes.

Suppose that, at a certain moment in a scene, someone comes in with a message. If I let him approach quite slowly, his arms hanging at his side, and go right up to the person to whom he is to deliver the message before he begins to speak (I am not inventing, I have seen this kind of thing over and over again!) then, so far as the spectator is concerned, there has been no message at all. If, however, the messenger begins to speak from as far away as possible, speaking also rather loud, louder than his fellow actors—then he does bring a message! As he comes nearer, he can draw back his head a little. That will create the impression that he knows very well what he has to say. And if he brings good news, he may add the gesture of holding up the right hand, with fingers outstretched. As a matter of fact, all that I have been saying applies to a message of good news. If it were a case of bad news, the messenger would have to comport himself differently. He would have to come in slowly, as though unwillingly, and then suddenly stop short and with tightly clenched hands deliver his message. The actor will of course be free to modify all this as he feels right, but he must at all events not make this gesture (hands crossed on the breast).

These are some of the things into which one has gradually to work one's way. I give them as examples and intend them to be received as such, not as instructions. As we have seen, all training for the stage should be of this character. What the student has to receive is by no means a set of rules; rather is his training intended to have a stimulating effect upon his own activity. Particular instances are put before him which are then capable of manifold variation.

8. Innere Anpassung an das bildhafte und plastisch gestaltete Sprachliche

Wir werden nun, um dasjenige, was in den letzten Betrachtungen gesagt worden ist, weiter zu erhärten, heute es zunächst zu tun haben mit dem Anhören einer durch Frau Dr. Steiner vorzubringenden Rezitation. Wir werden eine dramatische Szene hören, welche durch ihre eigene Gestaltung in einer besonderen Weise veranschaulichen kann, wie derjenige, der Bühnenkunst sucht, in die Sprachgestaltung hineinkommen kann.

Dieses Hineinkommen in die Sprachgestaltung beruht in vieler Beziehung darauf, daß eine gewisse innere Anpassung an das plastisch Gestaltete und Bildhafte des Sprachlichen geschehen kann. Man wird leicht Mühe haben, aus einer gewissen, ich möchte es nennen, Grauheit der Sprache im Dramatischen oder überhaupt im Rezitieren herauszukommen. Und Grauheit der Sprache nenne ich das Haftenbleiben bei der Prosagestaltung, wie man es im Leben gewohnt ist.

Daß man nach dieser Richtung eine Art Reformbewegung wird eintreten lassen müssen, geht wohl schon daraus hervor, daß in der letzten Phase der Entwickelung der schauspielerischen Kunst, welche ins Unkünstlerische hineingeführt hat, hauptsächlich angestrebt worden ist, sozusagen kunstlos zu sprechen, beim Sprechen nur an dasjenige zu appellieren, was in naturalistischer Weise aus dem gewöhnlichen Leben hergenommen werden kann. Man darf sogar sagen: In vieler Beziehung ist es nach dieser Richtung dem Naturalismus gelungen, sogar in seiner Art Ausgezeichnetes, aber nicht eigentlich Künstlerisches zu leisten.

Man konnte manchmal in den letzten Jahrzehnten ganz erstaunt sein, diesem oder jenem naturalistischen Versuch auf der Bühne beizuwohnen, denn man stand vor der Erscheinung, daß ein Stil, der das Dargestellte in eine gewisse künstlerische Sphäre hebt, überhaupt nicht mehr gesucht worden ist; dagegen fühlte man sich oft in die reinste Wirklichkeit, die man ja auch im gewöhnlichen Leben hat, hineinversetzt. Aber man möchte da ganz trivial sagen: Dazu geht man schließlich nicht gerade ins Theater.

Derjenige, der reinen Naturalismus in der künstlerischen Darstellung sucht, der gleicht einem Menschen, der nicht ein künstlerisch gemaltes Porträt haben will, dem das gar nicht gefällt, sondern der eigentlich nur eine Photographie haben möchte, vielleicht eine Farbenphotographie, weil er diese besser versteht. Aber gerade das Hinaufheben ins Künstlerische besteht darinnen, daß man mit ganz anderen Mitteln Wahrheit in der Kunst offenbart, als die Natur mit ihren Mitteln unmittelbar Wahrheit offenbart.

Wahrheit muß da sein in der Natur; Wahrheit muß da sein in der Kunst. Aber die Wahrheit in der Natur leuchtet dem Geiste entgegen; aus der Wahrheit in der Kunst leuchtet der Geist heraus. Und wenn man sich an solch eine Sache hält, dann bedeutet das, daß man den Weg zum Stil aus innerem künstlerischen Bedürfnis heraus suchen und auch finden will.

Daher ist es eine gute Übung, auch einmal die Sprachorgane hineinzubringen in ein Sprechen, das abweichen muß von dem gewöhnlichen naturalistischen Sprechen, durch seine eigene, individuelle Eigenart abweichen muß. Und wir werden sehen, wie das Sprachgestaltende von demjenigen abweichen muß, was im gewöhnlichen Leben normal vorhanden ist, indem wir uns die Szene anhören aus Lessings «Minna von Barnhelm», in welcher der Riccaut de la Marliniere auftritt, der nicht so sprechen kann, wie man gewöhnlich spricht, weil er Franzose ist und deutsch spricht. Da ist einfach durch die Natur der Sache die Stilisierung notwendigerweise gegeben. Und er schaltet ja immerfort dem Deutschen Französisches ein, spricht das Deutsche mit französischer Intonation.

Wenn man an solchen Dingen die Sprachgestaltung übt, so kommt man schon in jene Geläufigkeit hinein, die Stil hat, und aus diesem Grunde wollen wir uns diese Szene einmal anhören aus «Minna von Barnhelm».

Frau Dr. Steiner: Riccaut de la Marlinière kommt in das Hotelzimmer, wo er glaubt, den Major Tellheim zu finden.

RICCAUT (noch innerhalb der Szene). Est-il permis, Monsieur le Major?

FRANZISKA. Was ist das? Will das zu uns? (Gegen die Türe gehend.)

RICCAUT. Parbleu! Ik bin unriktig-Mais non-Ik bin nit unriktig.-C'est sa chambre?

FRANZISKA. Ganz gewiss, gnädiges Fräulein, glaubt dieser Herr, den Major von Tellheim noch hier zu finden.

RICCAUT. Iss so !-Le Major de Tellheim; juste, ma belle enfant, c'est lui que je cherche. Où est-il?

FRANZISKA. Er wohnt nicht mehr hier.

RICCAUT. Comment? nok vor vierunswanzik Stund hier logier? Und logier nit mehr hier? Wo logier er denn?

DAS FRÄULEIN. (die auf ihn zukommt) Mein HerrRICCAUT. Ah, Madame-Mademoiselle-Ihro Gnad, verzeih-

DAS FRÄULEIN. Mein Herr, Ihre Irrung ist sehr zu vergeben, und Ihre Verwunderung sehr natürlich. Der Herr Major hat die Güte gehabt, mir, als einer Fremden, die nicht unterzukommen wusste, sein Zimmer zu überlassen.

RICCAUT. Ah voilà de ses politesses! C'est un très galant homme que ce Major!

DAS FRÄULEIN. Wo er indes hingezogen - wahrhaftig, ich muss mich schämen, es nicht zu wissen.

RICCAUT. Ihro Gnad nit wiss? C'est dommage; j'en suis fâché.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Ich hätte mich allerdings darnach erkundigen sollen. Freilich werden ihn seine Freunde noch hier suchen.

RICCAUT. Ik bin sehr von seine Freund, Ihro Gnad. DAS FRÄULEIN. Franziska, weisst du es nicht?

FRANZISKA. Nein, gnädiges Fräulein.

RICCAUT. Ik hätt ihn zu spreck, sehr notwendik. Ik komm ihm bringen eine nouvelle, davon er sehr fröhlik sein wird.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Ich bedaure um so viel mehr. Doch hoffe ich vielleicht bald ihn zu sprechen. Ist es doch gleichviel, aus wessen Munde er diese gute Nachricht erfährt, so erbiete ich mich, mein Herr.

RICCAUT. Ik versteh.-Mademoiselle parle francais? Mais sans doute; teile que je la vois!-La demande etait bien impolie; vous me pardonnerez, Mademoiselle.-

DAS FRÄULEIN. Mein Herr?

RICCAUT. Nit? Sie sprek nit französisch, Ihro Gnad?

DAS FRÄULEIN. Mein Herr, in Frankreich würde ich es zu sprechen suchen. Aber warum hier? Ich höre ja, dass Sie mich verstehen, mein Herr. Und ich, mein Herr, werde Sie gewiss auch verstehen; sprechen Sie, wie es Ihnen beliebt.

RICCAUT. Gutt, gutt! Ik kann auk mik auf Deutsch explicier.-Sachez done, Mademoiselle.-Ihro Gnad soll also wiss, dass ik komm von die Tafel bei der Minister-Minister von-Minister von-wie heiss der Minister da drauss? in der lange Strass?-auf die breite Platz?

DAS FRÄULEIN. Ich bin hier noch völlig unbekannt.

RICCAUT. Nun, die Minister von der Kriegsdepartement.—Da haben ik zu Mittag gespeisen—ik speisen à l'ordinaire bei ihm—und da iss man gekommen reden auf der Major Tellheim; et le Ministre m'a dit en confidence, car Son Excellence est de mes amis, et il n'y a point de mysteres entre nous-Seine Excellenz, will ik sag, haben mir vertrau, dass die Sak von unserm Major sei auf dem point zu enden, und gutt zu enden. Er habe gemakt ein rapport an den Könik, und der Könik habe darauf resolvir, tout-à-fait en faveur du Major.—Monsieur, m'a dit Son Excellence, Vous comprenez bien, que tout depend de la manière, dont on fait envisager les choses au Roi, et vous me connaissez. Cela fait un très joli garçon que ce Tellheim, et ne sais-je pas que vous l'aimez? Les amis de mes amis sont aussi les miens. Il coute un peu eher au Roi ce Tellheim, mais est-ce que Pon sert les Rois pour rien? Il faut s'entr'aider en ce monde; et quand il s'agit de pertes, que ce soit le Roi qui en fasse, et non pas un honnête-homme de nous autres. Voila le principe, dont je ne me dépars jamais.-Was sag Ihro Gnad hierzu? Nit wahr, das iss ein brav Mann? Ah! que Son Excellence a le coeur bien placé! Er hat mir au reste versiker, wenn der Major nit schon bekommen habe une Lettre de la main-eine Könikliken Handbrief, dass er heut infailliblement müsse bekommen einen.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Gewiss, mein Herr, diese Nachricht wird dem Major von Tellheim höchst angenehm sein. Ich wünschte nur, ihm den Freund zugleich mit Namen nennen zu können, der soviel Anteil an seinem Glücke nimmt.—

RICCAUT. Mein Namen wünscht Ihro Gnad?-Vous voyez en moi-Ihro Gnad seh in mik le Chevalier Riccaut de la Marlinière, Seigneur de Prêt-au-val, de la Branche de Prensd'or.-Ihro Gnad steh verwundert, mik aus so ein gross, gross Familie zu hören, qui est veritablement du sang Royal.-I1 faut le dire, je suis sans doute le cadet le plus avantureux, que la maison a jamais eu-lk dien von meiner elfte Jahr. Ein affaire d'honneur makte mik fliehen. Darauf haben ik gedienet Sr. Päpstlichen Eilikheit, der Republik St. Marino, der Kron Polen, und den Staaten General, bis ik endlich bin worden gezogen hieher. Ah, Mademoiselle, que je voudrais n'avoir jamais vu ce pays-là! Hätte man mik gelass im Dienst von den Staaten-General, so müsst ik nun sein aufs wenikst Oberst. Aber so hier immer und ewig Capitaine geblieben, und nun gar sein ein abgedankte Capitaine.?

DAS FRÄULEIN. Das ist viel Unglück.

RICCAUT. Oui, Mademoiselle, me voila réforme, et par-1à mis sur le pavé!

DAS FRÄULEIN. Ich beklage sehr.

RICCAUT. Vous êtes bien bonne, Mademoiselle.-Nein, man kenn sik hier nit auf den Verdienst. Einen Mann wie mik, su reformir-Einen Mann, der sik nok dasu in diesem Dienst hat rouinir!-Ik haben dabei sugesetzt, mehr als swansik tausend livres. Was hab ik nun? Tranchons le mot; je n'ai pas le sou, et me voilä exactement vis-à-vis du rien.—

DAS FRÄULEIN. Es tut mir ungemein leid.

RICCAUT. Vous êtes bien bonne, Mademoiselle. Aber wie man pfleg zu sagen: ein jeder Unglück schlepp nak sik seine Bruder; qu'un malheur ne vient jamais seul: so mit mir arrivir. Was ein honnête-homme von mein extraction kann anders haben für ressource, als das Spiel? Nun hab ik immer gespielen mit Glück, so lang ik hatte nit von nöthen das Glück. Nun ik ihr hätte von nöthen, Mademoiselle, je joue avec un guignon, qui surpasse toute croyance. Seit funfzehn Tag ist vergangen keine, wo sie mik nit hab gesprenkt. Nok gestern hab sie mik gesprenkt dreimal. Je sais bien, qu'il y avait quelque chose de plus que le jeu. Car parmi mes pontes se trouvaient certaines dames-Ik will niks weiter sagen. Man muss sein galant gegen die Damen. Sie haben auk mik heut invitir, mir su geben revanche; mais-Vous m'entendez, Mademoiselle-Man muss erst wiss, wovon leben, ehe man haben kann, wovon su spielen.—

DAS FRÄULEIN. Ich will nicht hoffen, mein Herr

RICCAUT. Vous êtes bien bonne, Mademoiselle-

DAS FRÄULEIN. (nimmt die Franziska bei Seite) Franziska, der Mann dauert mich im Ernste. Ob er mir es wohl übel nehmen würde, wen ich ihm etwas anböte?

FRANZISKA. Der sieht mir nicht darnach aus.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Gut!-Mein Herr, ich höre—dass Sie spielen; dass Sie Bank machen? ohne Zweifel an Orten, wo etwas zu gewinnen ist. Ich muss Ihnen bekennen, dass ich—gleichfalls das Spiel sehr liebe—

RICCAUT. Tant mieux, Mademoiselle, tant mieux! Tous les gens d'esprit aiment le jeu a la fureur.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Dass ich sehr gerne gewinne; sehr gern mein Geld mit einem Manne wage, der - zu spielen weiss. Wären Sie wohl geneigt, mein Herr, mich in Gesellschaft zu nehmen? mir einen Anteil an Ihrer Bank zu gönnen?

RICCAUT. Comment, Mademoiselle, vous voulez être de moitie avec moi? De tout mon coeur.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Fürs erste nur mit einer Kleinigkeit-(Geht und langt Geld aus ihrer Schatulle.)

RICCAUT. Ah, Mademoiselle, que vous etes charmante!—

DAS FRÄULEIN. Hier habe ich, was ich unlängst gewonnen, nur zehn Pistolen-ich muss mich zwar schämen, so wenig—

RICCAUT. Donnez toujours, Mademoiselle, donnez. (Nimmt es.)

DAS FRÄULEIN. Ohne Zweifel, dass Ihre Bank, mein Herr, sehr ansehnlich ist.—

RICCAUT. Jawohl, sehr ansehnlik. Sehn Pistol? Ihro Gnad soll sein dafür interessir bei meiner Bank ein Dreiteil, pour le tiers. Swar auf ein Dreiteil sollen sein—etwas mehr. Dok mit einer schönen Damen muss man es nehmen nit so genau. Ik gratulir mik, su kommen dadurk in liaison mit Ihro Gnad, et de ce moment je recommence à bien augurer de ma fortune.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Ich kann aber nicht dabei sein, wenn Sie spielen, mein Herr.

RICCAUT. Was brauk Ihro Gnad dabei su sein? Wir andern Spieler sind ehrlike Leut unter einander.

DAS FRÄULEIN. Wenn wir glücklich sind, mein Herr, so werden Sie mir meinen Anteil schon bringen. Sind wir aber unglücklich?

RICCAUT. So komm ik holen Rekruten. Nit wahr, Ihro Gnad?

DAS FRÄULEIN. Auf die Länge dürften die Rekruten fehlen. Verteidigen Sie unser Geld daher ja wohl, mein Herr.

RICCAUT. Wofür seh mik Ihro Gnad an? Für ein Einfalspinse? für eine dumme Teuf?

DAS FRÄULEIN. Verzeihen Sie mir?

RICCAUT. Je suis des bons, Mademoiselle. Savez-vous ce que cela veut dire? Ik bin von die Ausgelernt-

DAS FRÄULEIN. Aber doch wohl, mein Herr—

RICCAUT. Je sais monter un coup-

DAS FRÄULEIN. (verwundert) Sollten Sie?

RICCAUT. Je file la carte avec une adresse?

DAS FRÄULEIN. Nimmermehr!

RICCAUT. Je fais sauter la coupe avec une dextérité—

DAS FRÄULEIN. Sie werden doch nicht, mein Herr?

RICCAUT. Was nit? Ihro Gnad, was nit? Donnez-moi un pigeonneau à plumer, et-

DAS FRÄULEIN. Falsch spielen? betrügen?

RICCAUT. Comment, Mademoiselle? Vous appelez cela betrügen? Corriger la fortune, l'enchaîner sous ses doigts, être stir de son fait, das nenn die Deutsch betrügen? Betrügen! O, was ist die deutsch Sprak für ein arm Sprak! für ein plump Sprak!

DAS FRÄULEIN. Nein, mein Herr, wenn Sie so denken?

RICCAUT. Laissez-moi faire, Mademoiselle, und sein Sie ruhig! Was gehen Sie an, wie ik spiel ?—Gnug, morgen entweder sehn mik wieder Ihro Gnad mit hundert Pistol, oder seh mik wieder gar nit.—Votre tres-humble, Made¬moiselle, votre très-humble—(Eilends ab.)

DAS FRÄULEIN. (die ihm mit Erstaunen und Verdruss nachsieht) Ich wünsche das letzte, mein Herr, das letzte!

Nun, meine lieben Freunde, warum brauchen wir eigentlich Sprachgestaltung als eine besondere Kunst der dramatischen Darstellung?

Wenn man dem Bühnenkünstler gegenübersteht, so handelt es sich darum, daß von Kunst dann nicht die Rede sein kann, wenn man ihm so gegenübersteht, wie man einem Unterredner im gewöhnlichen Leben gegenübersteht. Einem Unterredner im gewöhnlichen Leben steht man gegenüber, indem man seine Worte anhört und eigentlich auf den Klang der Worte, auf die Intonierung, auf die Sprachgestaltung einen möglichst geringen Wert legt. Man hört eigentlich nur so zu in bezug auf die Wortgestaltung, auf die Sprachgestaltung, wie man durch eine durchsichtige Scheibe hinschaut auf dasjenige, was hinter der durchsichtigen Scheibe ist. Das Wort ist gewissermaßen für das gewöhnliche Leben durchsichtig geworden, sagen wir, durchhörlich geworden. Man achtet nicht auf seine Eigengestaltung. Das muß in der dramatischen Darstellungskunst, der Bühnenkunst, wiederum angestrebt werden, daß das Wort selbst gehört wird; daß man nicht bloß durch das Wort wie durch eine durchsichtige Scheibe den Wald, so durch das Wort auf dasjenige schaut, was man vom anderen verstehen will, was einem der andere inhaltlich, gedanklich, empfindungsgemäß und so weiter sagen will, sondern daß man das Wort selber hört und im Hören des Wortes einen gewissen Inhalt erlebt. Aber weil das Gedankliche eigentlich der Tod der Kunst ist, ist es in dem Augenblicke, wo die Offenbarung eines Wesenhaften ins Gedankliche übergeht, mit der Kunst schon vorbei. Man muß hören, sehen dasjenige, was die Kunst darstellen will.

Nun aber hat man es in der Bühnenkunst mit Menschen zu tun, die ja auch denken, empfinden; und die Darstellung bezieht sich auf Menschen. Das ist die Hauptsache. Es wird einem daher gerade deshalb, weil man das Wort gestalten muß, etwas vom Menschen verlorengehen im Worte, das gestaltet ist, das einen künstlerischen Eigenwert überall aufweist. Das muß von anderer Seite her kommen. Und das kann in der Bühnenkunst nur kommen von dem Mimischen, von der Geste, von der Gebärde.

Damit aber wird schon der Übergang zu demjenigen gefunden, was die bloße Rezitations- und Deklamationskunst hinüberführt in die eigentliche Bühnenkunst, was notwendig macht, daß es eine richtige Bühnenschulung gäbe, eine richtige Schauspielerschulung gäbe.

Wiederum kann ja nur, ich möchte sagen, das Ideal der Schauspielerschulung mit Bezug auf das Mimische, das Gebärdenhafte hier dargelegt werden. Denn unter den heutigen Verhältnissen wird nur in mehr oder weniger großer Entfernung sich derjenige, der Bühnenkunst übt, dem nähern können, was in dieser Beziehung ideal ist. Aber gerade dutch das Hinstellen desjenigen, was eigentlich da sein müßte, was angestrebt werden müßte, wird man auch in beschränkteren Verhältnissen den Weg finden zu der eben dutch die Verhältnisse bedingten Annäherung.

Und so wollen wir denn einmal die Frage aufwerfen: Wie müßte man etwa die schauspielerische Schulung gestalten? - Da aber möchte ich gleich von vornherein etwas sagen, was Mißverständnisse aus dem Wege räumen kann. Mit Bezug auf die Bühnenkunst, gerade deshalb, weil man es mit lebendigen Menschen und ihren Ausdrucksformen zu tun hat, kann man selbst im Schulmäßigen, das was sein muß, eigentlich nur immer so vorgehen, daß man Beispiele gibt, das heißt, daß man die Anleitungen so gibt, daß sie als Beispiele aufgefaßt werden können; gewissermaßen immer einen Fall unter vielen gibt. Denn die Freiheit des Künstlers muß gerade im Bühnenmäßigen in alleräußerster Weise respektiert werden.

Es kann sich nicht darum handeln, daß man Anweisungen in der Schule empfängt, die in pedantischer Weise festgehalten werden müssen, sondern daß die Anweisungen so gegeben werden, wie man es eben gut machen kann, aber die völlige Freiheit gelassen wird, nun in dem Geiste solcher Anweisungen weiterhin gestaltend zu wirken. So sind die Dinge gemeint, die ich nun vorbringen werde.

Sehen Sie, ich habe gleich im Beginne dieser Auseinandersetzungen darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie man zum Beispiel in der griechischen Gymnastik etwas hat, was instinktiv der menschlichen Organisation abgenommen ist, indem die fünf Betätigungen, Laufen, Springen, Ringen, Diskuswerfen, Speerwerfen, tatsächlich mit einer gewissen Steigerung aus demjenigen heraus kommen, was die menschliche Natur verlangt.

Nun wird man gemäß der Entwickelung ins Moderne herein für heutige gymnastische Bewegungen die alten Formen etwas modifizieren müssen; aber im wesentlichen werden wir dennoch eine gute Vorstellung bekommen, wenn wir Laufen, Springen, Ringen und so weiter uns von dem Geist beseelt denken, wie es in der griechischen Gymnastik der Fall war. Denn diese griechische Gymnastik hatte etwas Geniales und wirkte in ihrer Art wirklich echt künstlerisch und echt geistig. Natürlich, die Kürze der Zeit hindert uns daran, einzugehen darauf, wie die Dinge etwas modifiziert werden können; aber dasjenige, was eigentlich gemeint ist, werden Sie auch ersehen, wenn ich die Auseinandersetzung so gestalte, daß ich einfach die Worte für die griechische Gymnastik gebrauche.

Eine eigentliche Schauspielschule sollte mit einer in diesem griechischen Geiste gehaltenen Gymnastikschule beginnen, und es sollte tichtig in moderner Gestalt geübt werden: Laufen, Springen, Ringen, Diskuswerfen oder etwas ähnliches, Speerwerfen oder etwas ähnliches. Warum? Nicht, damit der Schauspieler das kann, denn ich will den Schauspieler selbstverständlich nicht zum Ausüber solcher Künste machen. Nur dadurch kann die Schauspielkunst sich veredeln, daß sie nicht in das Zirkusmäßige hinein «reinhardtet», sondern daß sie sich ablöst von allem Zirkusmäßigen, daß sie sich tatsächlich annähert an die edle Wiedergabe des Dichterisch-Künstlerischen. Aber es handelt sich dabei um etwas ganz anderes, wenn die Schauspielschule mit Gymnastik beginnen soll. Es handelt sich darum, daß der Schauspieler gerade dieses in ihm Selbstverständlichwerden der Wortgestaltung durch Gymnastik lernen soll. Das muß Instinkt werden.

Aber Instinkt werden muß auch das Mimische, das Gebärdenhafte; das erst recht. Es soll auf der einen Seite nicht naturalistisch sein, es soll stilvoll, künstlerisch sein, es soll sozusagen wie aus der geistigen Welt heraus wirken; aber es soll dem Schauspieler so selbstverständlich werden wie dem gewöhnlichen Menschen seine Aufführung im gewöhnlichen Tagesleben, wenn er nicht kokett ist, nicht ein eitler Fatzke ist, sondern sich benimmt, wie man sich eben selbstverständlich benimmt. So auch soll das künstlerische Gestalten des Wortes, der Gebärde, der Physiognomie dem Schauspieler selbstverständlich werden.

Er muß also in gewissem Sinne dem bewußten Erlernen ein instinktives Erleben beimischen, sonst werden die Dinge nicht selbstverständlich, sonst werden sie immer gemacht erscheinen.

Nun lernt man aber, wenn man kunstvoll laufen lernt, auf der Bühne gehen so, daß das Gehen das Wort artikuliert. Laufen : Gehen.

Laufen: Gehen, so, daß das Gehen das Wort artikuliert.

Denn, sehen Sie, alles, was der Verstand des Zuschauers erfassen soll, was nicht gehört werden soll im gestalteten Worte, soll man aus der Gebärde, aus dem Mimischen verstehen.

Was der Schauspieler spricht, soll man anhören. Was der Schauspieler tut, das soll man mit einem gewissen Instinkt verstehen, die Gebärde, das Mienenspiel. Da darf der Verstand heran, weil er das im gewöhnlichen Leben nicht tut, wenigstens nicht begreifend tut, weil da Künstlerisches eintreten kann.

Beim Springen lernt man jenes modifizierte Gehen auf der Bühne, ob man langsam zu gehen hat bei irgendeiner Passage, ob man schnell zu gehen hat, man lernt es instinktiv in der Anpassung an jene Wortgestaltungen, die ich in diesen Vorträgen als das Schneidende der Worte, das Volle der Worte bezeichnet habe, das langsam Gezogene der Worte, das kurz Abgemessene, das Harte, das Sanfte. Das alles muß in entsprechender Weise auf der Bühne begleitet werden mit modifiziertem Gehen. Weder derjenige, der auf der Bühne spricht, noch derjenige, der zuhört, kann in willkürlicher Weise gehen. In bezug auf die Schnelligkeit des Gehens muß man richtig Schnelligkeit und Langsamkeit des Gehens lernen, oder jene völlige Langsamkeit, die Stehen bedeutet, nach dem, was am Worte schneidend oder voll ist, langgezogen oder hart oder sanft ist. Das aber lernt man instinktiv am Springen. Da lernt man das modifizierte Gehen in Anpassung an den Charakter des Wortes.

Springen: modifiziertes Gehen in Anpassung an den Charakter der Worte

Sehen Sie, das ist in gewissem Sinne ein Geheimnis der menschlichen Natur, insofern diese menschliche Natur in die Schauspielkunst hineingeraten soll, daß instinktiv im Springen das angeeignet wird. Man kann das natürlich nicht beweisen, sondern man muß es erleben. Und es wird erlebt, wenn es getan wird. Sie können versichert sein, gewisse Dinge im Leben müssen sich eben am Leben praktisch erlernen, und alles Herumtheoretisieren hat keinen Wert.

Im Ringen lernt man am besten instinktiv, was man für Handbewegungen und Armbewegungen während des Sprechens machen soll. Das lernt man im Ringen.

Ringen: Hand- und Armbewegungen

Im Diskuswerfen, bei dem das Gesicht sich übt, nachzuschauen, sich anzupassen an die Zielrichtung und an den ganzen Weg desjenigen, was man wirft, sich anzupassen auch an die Handbewegung selber, im Diskuswerfen, so paradox es klingt, lernt man das Mienenspiel; geläufiges Mienenspiel, Beherrschen der Muskeln zum Mienenspiel, man lernt es im Werfen. Es kann ja auch Ballwerfen oder irgendein anderes Werfen sein, aber ich nenne es mit dem griechischen Worte Diskuswerten.

Diskuswerfen: Mienenspiel.

Und dasjenige, was das Paradoxeste ist, was man natürlich ganz und gar nicht beweisen kann, was aber erlebt werden muß - es kann ja auch mit Stöcken geschehen statt mit Speeren, aber es sollte geschehen -: im Speerwerfen lernt man sprechen. Das heißt, es erfährt die Sprache im Speerwerfen diejenige Selbstverständlichkeit, daß sie als Sprache wirkt, nicht als Ausdruck des Gedankens wirkt, sondern als Sprache wirkt. Daher muß der Schauspieler auch im Werfen von solchen Gegenständen erzogen werden, die eben Stock oder Speer sind. Denn wie man da innerlich achtgeben muß, das zieht die Sprache aus dem bloßen Intellekt heraus in die Sprachorgane und ihre Gestaltung. Speerwerfen ist direkt die Grundlage des Sprechens.

Speerwerfen: Sprache.

Natürlich, das ganz im allgemeinen. Dazu kommen die besonderen Dinge, die wir schon durchgemacht haben. Aber soll wirklich schulmäßig vorgegangen werden, dann handelt es sich darum, daß man ein instinktives Verständnis für dasjenige hervorruft, was in den letzten Stunden gerade in bezug auf die Sprachgestaltung durch das Werfen von länglichen stock- oder speerartigen Gegenständen gesagt worden ist. Und wenn hier lauter solche Menschen sitzen würden, die sich längere Zeit etwas geübt hätten im Speerwerfen, so würde bei den Zuhörern gar kein Zweifel sein, daß das richtig ist, was ich gesagt habe. Man beweist diese Dinge eben nicht theoretisch, sondern man beweist sie durch die Trainierung desjenigen, der sie aufnehmen soll. Es ist schon einmal die richtige okkulte Trainierung für die Auffassung des schauspielerischen Sprechens das Speerwerfen.

Sie sehen also, wie diese Vorschule der Bühnenkunst eigentlich gestaltet sein muß. Wenn man in dieser Weise aus dem Geiste des Ganzen an die als künstlerisches Subjekt auftretende menschliche Persönlichkeit herankommt, dann wird man gerade die Details, um die es sich dann weiter handeln wird, nicht in pedantischer Art als Anweisungen nehmen, sondern als Anregungen. Und eigentlich muß in der Schauspielerschulung alles auf Anregungen beruhen, damit derjenige, der Schauspieler werden will, eine möglichst große Freiheit hat, dasjenige, was er gelernt hat, entweder so zu machen, wie er es gelernt hat, oder aus demselben Geiste heraus auch anders.

Das Wichtigste, was man zunächst in bezug auf die schauspieletische Darstellung zu erfassen hat, ist dieses, daß es in keinem Augenblicke auf der Bühne einen unbeschäftigten Schauspieler geben kann. Es darf keiner auf der Bühne stehen, der unbeschäftigt ist. Es ist ein schlimmer Augenblick, wenn einer redet und ein paar andere, die gleichzeitig, weil es die Szene gebietet, auf der Bühne sind, Maulaffen feilhalten, wie man im Deutschen sagt, das heißt, nichts tun. Derjenige, der redet, redet eben; die anderen, die zuhören, müssen unausgesetzt alles dasjenige mitmachen, was der Betreffende redet. Keiner darf unbeschäftigt sein. Sind vier auf der Bühne und einer redet, dann müssen die drei anderen im Mimischen, im Gebärdenhaften mitspielen.

Und das ist die Aufgabe einer richtigen, wirklichen Regiekunst, die für die Gestaltung des Bühnenbildes zu sorgen hat, daß in diesem Sinne nie ein unbeschäftigter Schauspieler auf der Bühne steht. Wenn ein Schauspieler auf der Bühne stehen und nun wirklich zuhören wollte, nicht nur Zuhören darstellen wollte, so wäre das ein künstlerischer Fehler. Das Zuhören mit allem inneren Erleben des Zuhörens darf nicht ein wirkliches Zuhören sein, naturalistisch, sondern es muß ein darstellendes Zuhören sein. Alles muß in die Darstellung einfließen. Dazu ist es notwendig, daß man überhaupt auf dasjenige eingeht, was eine mögliche, richtige Gebärde ist in Begleitung der Wortgestaltung. Naturalismus auf der Bühne wirkt puppenhaft. Und gerade dann, wenn man in den letzten Jahrzehnten den Eindruck hatte, daß die Leute da oben die Illusion der naturalistischen Wirklichkeit hervorrufen können, dann hatte man im künstlerischen Erfassen den Eindruck des Puppenhaften, das dem entgegengesetzt liegt. Daher muß man die innere Empfindung entwickeln für gewisse Zusammenhänge zwischen dem Mimischen, Gebärdenhaften, der Geste und dem gesprochenen Worte als Inhalt.

Wenn ein Mensch auf der Bühne etwas zu sagen hat, was darauf ausgeht, etwas Intimes zu bedeuten, dann muß der Zuschauer fühlen können, daß in der betreffenden Passage etwas, was auf intime Mitteilung hin berechnet ist, zum Ausdrucke kommt. Das würde er nie, wenn Sie auf der Bühne etwas Intimes sagen und dabei nach hinten gehen. Das wird er immer, wenn Sie das Gehen so einrichten, daß Sie von rückwärts nach vorne gehen. Wollen Sie Intimes auf der Bühne aussprechen, so handelt es sich immer darum, daß man die Bewegung von rückwärts nach vorne, vom Bühnenfond nach der Rampe macht.

Diese Dinge werden manchmal aus merkwürdigen Gründen durchbrochen. Ich kannte einen ausgezeichneten Schauspieler, der nun wirklich großartig war in vieler Beziehung, der aber nicht lernen wollte. Das gefiel ihm nicht, ich meine, die Rollen wollte er nicht lernen. Daher machte er dem Regisseur immer rechtes Unbehagen, denn er sagte: Kinder, Ihr mögt euch bewegen und hinstellen, wo Ihr wollt, ich stelle mich da her! -— Da war nämlich der Souffleurkasten, und da rührte er sich nicht weg. Im übrigen war er ausgezeichnet. Also es handelt sich schon darum, daß man wirklich in dem Künstlerischen darinnen lebt.

Nehmen wir aber an, wir haben auf der Bühne eine kleine Gruppe von Menschen, der wir irgend etwas mitteilen, was nicht auf Intimität berechnet ist, sondern eben auf Mitteilung berechnet ist. Da muß der Zuschauer den Eindruck bekommen: Die Sache geht denen ein, die auf der Bühne zuhören. — Wie die sich verhalten, die Zuhörer, darüber werde ich noch sprechen; wir müssen es jetzt von der einen Seite betrachten, von der Seite der Sprechenden. Habe ich auf der Bühne eine Gruppe um mich, und soll der Zuschauer den Eindruck bekommen, der Gruppe geht das ein, zu der ich spreche, dann muß ich mich etwas leise innerhalb der Gruppe zurückbewegen. Dann bekommt in der Perspektive des Zuschauers dieser Zuschauer den Eindruck: die verstehen es genau.

Wenn Sie aber die Versammlung, die Sie da vor sich haben, durchschreiten in der Richtung nach dem Zuschauer hin, dann bekommt der Zuschauer den Eindruck: das geht alles an ihren Ohren vorbei, sie verstehen nichts. Hier beginnt wirklich das innerlich Technische im Aufbau des Bühnenmäßigen. Das sind die Elemente, aus denen heraus das Bühnenbild gestaltet werden muß. Wenn man heute irgendwo ein Dramatisches aufgeführt sieht, da kann man schon gar nicht recht herankommen, denn fortwährend geschieht das, daß sich der eine eine Zigarette anzündet, pafft, der andere zündet sich eine Zigarette an, und das Anzünden von Zigaretten wird als eine besondere Geschicklichkeit der bühnenmäßigen Darsteller entwickelt.

Ja, ich habe gesehen, daß man Szenen liebt, in denen damit begonnen wird, daß jemand ankommt auf der Bühne, zunächst möglichst lang nichts redet, das Wort ganz in den Hintergrund treten läßt. Er setzt sich nieder, eigentlich räkelt sich hin, zieht langsam den einen Stiefel aus, um naturalistisch anzudeuten, daß er ziemlich spät am Abend ankommt, zieht sich den einen Hausschuh an - da hat er noch immer kein Wort geredet -, zieht sich den anderen Stiefel aus, zieht sich den anderen Hausschuh an — hat noch immer kein Wort geredet. Dann zieht er sich den Rock aus, macht Schritte durch das Zimmer, wie es eben ein Mensch macht, der sich abends den Rock auszieht. Dann zieht er sich den Schlafrock an, geht irgendwie zum Alkoven und heizt, damit es ihm nicht kalt wird. Er hat noch immer nichts geredet. Nun bereitet er sich vor, ja - irgend etwas jetzt zu tun, was halt ein Mensch tut, wenn er den Schlafrock angezogen hat. Zwischen Stiefelausziehen und Schlafengehen kann ja Verschiedenes geschehen -, aber zu diesem Mienenspiel, Gebärdenspiel braucht man natürlich kein besonderes Studium, sondern den Glauben, daß man weiß, wie es die Leute machen, wenn sie zu Hause sind, und ein bißchen Frechheit dazu, sich in diesen Dingen auch zu zeigen. Weiter ist gar nichts dazu notwendig.

Das führt natürlich nicht zu einer wirklichen Bühnenkunst. Das führt unter Umständen zu Schrecklichem. Denn wenn dann die Schauspieler dasjenige in ihrem Leben nicht gesehen haben, was sie naturalistisch darstellen sollen, dann kommt etwas Schreckliches heraus. Ich habe neulich zum Beispiel eine Darstellung gesehen, in der eine Szene am Hofe dargestellt wurde. Man sah allen Schauspielern an, daß sie niemals einen Hof gesehen hatten! Ja, sehen Sie, diese Dinge muß man sich schon vor die Seele stellen, damit man einen Sinn dafür bekommt, wie die Dinge gemacht werden müssen, wenn sie künstlerisch sein sollen. Und es ist wirklich so, daß der echte künstlerische Dichter und der echte Schauspieler sich da in ihren Gesinnungen treffen werden.

Sehen Sie sich Goezhes Hauptdramen an, ob da viele szenische Anweisungen drinnen sind, wie es der Schauspieler machen soll? Möglichst wenig! Sehen Sie sich daraufhin den «Tasso» oder die «Iphigenie» an, da ist dem Schauspieler die nötige Freiheit gelassen. Und das ist richtig, Goethe hat natürlich in der Zeit, da er schon mit einigen ganz guten Schauspielern zu tun hatte, in dieser Beziehung nicht nur durch inneren Impetus, der ja natürlich reichlich vorhanden war, aber auch durch den Umgang mit Schauspielern manches gelernt. Die Corona Schröter, die hätte, wenn Goethe ihr hätte ins einzelne hineingehende Anweisungen, wie mancher moderne Dichter, geben wollen, gesagt: Na, Herr Geheimrat, daraus wird doch nichts, das mache ich, wie es mir paßt.

Dagegen schen wir, wie gerade die modernen Bühnendichter manchmal seitenlange szenische Anweisungen haben. Es ist schrecklich dann, diese Dinge zu lesen, denn derjenige, der geraden Sinn hat, liest doch nicht, wenn er das Buch vor sich hat, die Szenenanweisungen. Die sollen doch folgen für des Lesers Phantasie aus demjenigen, was gesprochen wird.

Nun hat man heute wirklich Dramen, bei denen seitenlange Anweisungen da sind, dann kommt einmal eine Seite mit Text dazwischen. Vergleichen Sie damit nur den «Tasso» oder die «Iphigenie». Gerade an solchen Erscheinungen sieht man den Niedergang der Bühnenkunst auch an den Dichtern.

Dasjenige, was der Schauspieler tun soll, das muß in seinem Instinkt sein. Bekommt er es als eine strikte Anweisung, dann wird es gemacht ausschauen. Aber in den Instinkt des Schauspielers kann eben vieles hineingehen.

Denken Sie sich hier die Bühne und den Zuschauerraum (siehe Zeichnung). Der Zuschauer sitzt da und hat zwei Augen. Hätte er diese zwei Augen nicht, so würde dem Schauspieler das ganze Mienenspiel und die ganze Gebärdenkunst nichts helfen. Aber diese zwei Augen sind nichts Totes, das man unberücksichtigt lassen darf, sondern etwas Lebendes. In diesen zwei Augen ruht vieles von dem, was oben auf der Bühne vorzugehen hat, weil es verstanden werden soll.

Nun ist das Eigentümliche unserer zwei Augen, daß sie in bezug auf das Auffassen nicht gleich sind. Auf das achtet man natürlich nicht im gewöhnlichen Leben und in der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft; aber sie sind nicht gleich. Das rechte Auge ist mehr eingeschult auf Verstehen, wenn es etwas anschaut; das linke Auge ist mehr eingestellt auf Interessehaben für dasjenige, das man anschaut.

So sitzt der Zuschauer gegen die Bühne:

Nehmen Sie nun an, Sie haben eine Passage im Stück, und es kommt Ihnen besonders darauf an und muß Ihnen aus der künstlerischen Intention heraus darauf ankommen, daß Sie mit der Passage das künstlerische Interesse des Zuschauers in Anspruch nehmen wollen, dann müssen Sie als Schauspieler von rechts nach links [vom Zuschauer aus gesehen] gehen. Dann empfängt das Auge im Anschauen von dem nach dieser Seite hier Gehen 5 den Eindruck des Interessanten. Ist die Passage länger, dann tun Sie gut, weil ja das Interesse etwas nachlassen darf, den Schauspieler auch zurückgehen zu lassen.

Das ist einfach durch die Augen vorgeschrieben.

Dagegen, habe ich eine Passage, mit der man weniger das Gefühlsinteresse erregen will, sondern mit der man vorzugsweise auf den Verstand des Zuschauers wirken will, auf das reine Verstehen, will man etwas erörtern, was ja im Drama sehr häufig vorkommt, dann muß der umgekehrte Weg eingeschlagen werden: der Schauspieler muß so gehen ↘: von links nach rechts.

Diese Dinge müssen eben gekannt sein. Es muß gekannt sein, wie störend es ist, wenn durch irgendeine Passage im Drama etwas das Interesse erregen soll und der Schauspieler bewegt sich so: ↘. Gar kein Interesse wird erweckt.

Das Interesse wird erweckt, wenn sich der Schauspieler so bewegt: ↙. Die Dinge sind eben so. Diese Dinge müssen gefühlt werden, wie überhaupt künstlerische Dinge gefühlt werden müssen.

Und ist man in der Lage, in dieser Art die Dinge anzuschauen, dann wird man aus diesem Geiste heraus in voller Freiheit die Gestaltung des Bühnenbildes bewirken können. Nehmen wir einmal an, es kommt in einem Drama vor, daß einer eine Botschaft bringt. Wenn ich den nun ganz langsam ankommen lasse, mit den Armen nach unten, und dann, wenn er vor denjenigen tritt, den er ansprechen soll, zu sprechen ihn anfangen lasse - ich erzähle das nicht, weil ich etwas erfinden will nach dieser Richtung, sondern weil ich das alles, und zwar sehr häufig gesehen habe -, da wird gar keine Botschaft gebracht, nämlich künstlerisch für den Zuschauer! Sondern eine Botschaft wird gebracht, wenn derjenige, der sie bringt, möglichst schon in der Entfernung anfängt zu reden und ziemlich laut redet, lauter als die übrigen Mitspielenden redet, schon in der Entfernung anfängt zu reden.

Bringt er dann die Botschaft näher, kommt er näher, dann ist es gut, wenn er den Kopf etwas nach rückwärts gewandt bewegt. Damit wird der Eindruck hervorgerufen, er weiß die Botschaft sehr gut.

Ist die Botschaft eine freudige Botschaft, dann kommt dazu, daß die Finger ausgestreckt werden: rechte Hand. Alles das, was ich im Grunde genommen jetzt von einer Botschaft sage, bezieht sich auf freudige Botschaft.

Ist die Botschaft eine traurige, muß man sich anders verhalten. Da handelt es sich darum, daß man zögernd allerdings ankommt, aber dann sichtbarlich stehenbleibt und mit angezogenen Fingern die Botschaft vorbringt — Freiheit hat man natürlich genug -, nicht aber so macht: Hände auf der Brust gekreuzt.

Das sind die Dinge, in die man sich allmählich hineinarbeiten muß, Beispiele sind es nur. Als Beispiele sind sie aufzufassen, nicht als Anweisungen. Aber alles Schulen in der Schauspielkunst beruht darauf, daß man die ganze Schulung nur als Anregung empfängt, so daß man sozusagen einen Fall durch die Schulung geschen hat, der in der mannigfaltigsten Weise variabel ist.

Da wollen wir dann morgen fortsetzen.

8. Inner adaptation to pictorial and sculptural language

In order to further substantiate what has been said in the last few reflections, we will now begin by listening to a recitation by Dr. Steiner. We will hear a dramatic scene which, through its own design, can illustrate in a special way how those who seek the art of the stage can enter into speech formation.

This entry into speech formation is based in many respects on a certain inner adaptation to the plastic and pictorial nature of language. It is easy to get stuck in what I would call a certain grayness of language in drama or in recitation in general. And by grayness of language I mean sticking to the form of prose, as we are accustomed to in everyday life.

The fact that a kind of reform movement will have to take place in this direction is already evident from the fact that in the last phase of the development of the art of acting, which has led to the non-artistic, the main aim has been to speak, so to speak, without art, to appeal only to what can be taken from ordinary life in a naturalistic way. One might even say that in many respects naturalism has succeeded in this direction, even in its own way, in achieving something excellent, but not actually artistic.