Speech and Drama

GA 282

15 September 1924, Dornach

XI. The Relation of Gesture and Mime to the forming of Speech

My dear Friends,

We must now go on to consider the question of how our dramatic performances can contribute to the artistic life of the community. We have spoken of what the actor should know and practise; how is all this to reach the public? How are we to ensure that our endeavours to give artistic form both to the whole picture of the stage and to the acting, shall awake an understanding for dramatic art?

In order to answer this question, it will be necessary to say a little more about the training that a school of dramatic art should give. Such a school will have to develop in the students a thorough and penetrating understanding of mime, and of gesturing in all its forms. We have already spoken of these in more general terms; but only when the actor becomes alive to the necessity for a fuller and more detailed understanding of mime and gesture, can we hope—I will not say to educate the public (the description of people as ‘educated’ has by now come to have very little meaning), let me rather say, only then can we hope to evoke in the public a true appreciation of art.

Let us therefore today continue our study of mime and gesture, going further into the kind of practical details that the professional actor needs to master. And here again I shall want you to take what I say not as rules but as examples, in the sense that I have explained.

We will begin with an expression in mime that is quickly recognisable and that is bound to follow at once on the emotion producing it. I mean, the mime for the emotion of anger.

We must first make sure that we understand how the emotion of anger works. When a person becomes angry, his muscles immediately grow taut, and then, after a little, slacken again. In real life, it is only the first part of the process that need claim our attention; but when we are studying how to act anger on the stage, we must see that the process is revealed in its entirety—first, tension; then, relaxation. And now, suppose we have a student who is to learn the mime and gesture that are relevant for the expression of anger, how is he to set about it?

When he has worked sufficiently at the cultivation of his feeling for the individual sounds (for that will always be the first thing to be studied in a school of dramatic art), then we can take with him some passage in a play where a character manifests anger, and let the passage be spoken for him by the reciter. I have explained to you before that this is always the best way for a student to learn gesturing; only later on should he unite gesture and word. The reciter, then, will speak the passage as it should be spoken. The student, who will of course be following carefully the content of the words, will have to accompany them the whole time with an i e feeling. As he listens, he lets the i e feeling ‘sound’ in him, inwardly—i e, i e. This will of itself give rise to an inner experience, which he will then go on to express instinctively in some movement or other—with arms or hands, or with clenched fists; first tightening the muscles (i) and then again letting them go slack (e): i e, i e, i e.

Please note that a physiological expression must always, without exception, be associated with a feeling for sound. It should be a strict rule for the student never in his practising to make any bodily movement or action without its being accompanied by a particular sound-feeling.

Suppose we want to present a person who has been passing through some deep experience of sorrow or of terror. The emotional experience is in a sense past and over, but it has left its mark upon him; how is this to be shown? The actor will have to come on to the stage with relaxed muscles; that should be his physiological condition. And invariably, as he practises, he will have to accompany the slackness of the muscles with the e mood.

Or again, consider how one would have to act someone who is anxious and troubled. Perhaps he comes on to the stage in this condition; or it may be that in the course of the scene he is distressed at something that is said to him. In either case, one should try to bring a light sound of ö (French eu in ‘feu’) into his speaking. This will mean that wherever we have to do with this feeling of trouble and concern, whether the person in question brings it with him or feels it arise in him through words he hears another speak, the actor will try to develop the mime in the ö mood—letting his hands fall slowly to his side and his eyelids droop. When I advise details of this kind, you must always remember that they are not intended to curtail the freedom of the individual artist; he is left to find his own way of carrying them out.

If the person in question is very sorely troubled or is thrown into a condition of acute concern, then his lips will want to close up and his tongue to cleave to the roof of his mouth when he has to speak. And if later on he has to speak again in reply to what another has said, he will continue to utter his words, wherever possible, with lips pressed together. That will have a wonderful effect; you will find that his words have just the right colouring. If you bring on the stage two interlocutors, the first saying something that grieves and troubles the second, and the second answering in such a way that he produces even his a sounds with compressed lips, then the impression that the audience instinctively receive of the effect that the words of the one are having upon the other, cannot fail to be of the right colouring.

Take an extreme case. One of them says: ‘Your brother has died.’ The other exclaims: ‘My brother! It can't be true!’ If the lips are at the same time pressed as near together as possible, the words will have their right colouring.

If it is found necessary, as will certainly be the case with a prolonged condition of care and anxiety, to help out the mime with a made-up pallor, then the make-up should be accompanied throughout by this kind of speaking, where the lips are all the time held more closely together than usual. A made-up pallor should, in fact, never appear on the stage without this mime.

It is, you must know, most important for the actor to realise that there are certain expressions of emotion that have to be represented with particular care upon the stage—not always as in real life. Sighing and groaning, for instance, can certainly play a part in the mime and gesture of the stage. They should never be practised by themselves; the student should be listening to a recited passage that displays pain or anxiety, a passage, however, that contains the implication that the sufferer is wanting to get over it. For when a person is completely overwhelmed with pain and sorrow, he does not groan or sigh; whereas one who would fain be rid of his suffering, one who is open to being comforted—he will sigh and groan. In real life this distinction may not always hold good; in art, however, it has to be strictly adhered to. If we mean our acting to have style, then groans and sighs can be allowed only when the person presented is going to find relief from his pain, to the extent anyway of being able to speak; he must not be struck dumb with sorrow. When therefore we have to reply on the stage to words that convey some shattering tidings, we should begin with groans and sighs—which we have also learned to produce with style. That will as it were open the way for us to speak.

Whenever some emotion has to be expressed, the student should on every single occasion practise with it some bodily movement or action which again must invariably have its connection with formed speech. Suppose, for example, you are listening to a speech that is sad and sorrowful. As you listen, you will move your head, being careful, however, to do so without changing countenance. Head movements, with the countenance in repose—that will be right for listening to a sorrowful passage. For then something else follows of itself. The diaphragm, with all that is below it, comes also into movement, begins to make movements that are a kind of reaction to the movements of the head. It comes about quite naturally; the correct head movement will ensure that the diaphragm and abdomen are set in motion in the right way. And never allow yourself to forget that every such bodily movement has always to be practised to the accompaniment of formed speech. This then will be the posture for an actor who is listening to the recital of a sorrowful passage: he will listen with full consciousness, shaking his head, but keeping his features still.

But now, let us say, you listen to a passage that leaves you cold, that has no interest for you. You will not move your head at all, you will simply stare with complete unconcern. It is not too much to say, for it is an established fact, that listening in this way with the countenance in repose and the head also quite still, as though one were on the point of falling asleep, gives rise to a slight glandular secretion, such as happens normally with a phlegmatic who is true to his temperament. This mime can indeed be a great help to you when you have to play the part of a phlegmatic, whilst the mime I gave before will help you to act a melancholic.

We have thus here definite suggestions for the acting of these two temperaments. An actor preparing himself for the presentation of melancholic characters should listen to sorrowful passages, keeping his face quiet and making movements with his head, letting these then call forth their natural reaction in his body. And one who wants to prepare himself for acting a phlegmatic part should assume the physiognomy of beginning to fall asleep—keeping his face in repose, letting his eyelids and nostrils droop, and with the upper lip unmoved by any kind of voluntary effort. As he listens in this attitude, that fine glandular secretion which always goes with a phlegmatic temperament will begin to take place in him. Things like this will help you to see the spirit that should animate all your work.

Suppose now you want to prepare a student for the part of a naive and sanguine character. You will have some sensational announcement read out to the actress or actor (for there can also be sanguine men!) and get her or him to make, while listening, powerful facial movements, movements also with the arms. Such gestures will lead instinctively into the impetuous and voluble kind of speaking that your student will need to develop.

Should you want to prepare an actor to present a choleric, you will choose for him a passage where the speaker is pouring out abuse. You will find plenty of such passages in Shakespeare. The student, as he listens, will have to knit his brows and clench his fists. He should also plant himself firmly on the ground with all his muscles tense. From knees downwards, the muscles of his calves should be held taut; and he should all the time be conscious of standing on the floor with the whole sole of his foot. Then he will be ready for the part.

For the practice of other arts, everyone knows we have to acquire a technique; and it is no different with the art of the stage. We have to acquire a technique that can start us off on the right road. And here I would like to draw your attention to two things in life that the science of today leaves unexplained. There are of course a great many things that science is unable to explain (do we not hear on every hand of the ‘boundaries of knowledge’?), but these are two that concern us in our present study. I mean laughing and weeping. Before these, there is for present-day science a ‘boundary of knowledge’ ; how laughing and weeping come about in man is admittedly an unsolved problem.

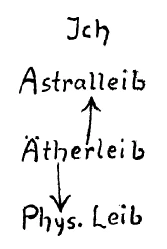

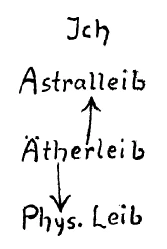

There is, however, no need for the problem to remain unsolved. Take weeping. What does weeping signify? Weeping always goes back to this: somewhere or other the ether body is taking hold too strongly of the physical body. When man finds this condition painful, he tries to call back the force that is working from the ether body into the physical body, and raise it in the direction of the astral body.

Ego Astral Body

Ether Body

Physical Body

He thus pours a counter-force into the astral body. The ether body is of course connected with the fluid element in man. So now you can see what happens. The ether body exerts its force in the direction, not of the physical but of the astral body; and the result of this, the projection of it in the physical, is that tears are released, the man weeps. And it is on this account that the shedding of tears brings relief.

Try now to let ä ring out clearly, try to enter deeply into the experience of ä. You will then gradually acquire a play of countenance that will need but a few little drops of water placed here (on the eyes) for it to be weeping. Yes, it will then be weeping; no need at all for real tears to well up from within Having made yourself completely at home in this play of countenance and become increasingly conscious of what your nose and eyes are doing when you say ä, then if you take from a cup a few drops of water and place them on your eyes, you are weeping. You are acting weeping to perfection.

We are here touching an important point. It is by no means our aim that sentimental spectators shall be able to say what I have heard said again and again of Eleanora Duse (but it was not true), that she wept on the stage. She shed real tears, so people said; and the statement was supposed to evoke one's enthusiasm for such an achievement. Similarly one has also frequently heard it asserted that Eleanora Duse, who was by nature quite pale, could raise a blush on the stage. Apparently she did blush; people only did not notice that she turned at the same time! Her face had been made up light on one side and darker on the other. It argues a little want of respect and proper appreciation to take for real some stage technique that can so successfully create an illusion. For illusions of this kind have to be consciously planned; one has to undergo a training for them—in this instance, by surrendering oneself wholly to the ä sound.

Going on now to consider laughter, we find that where laughter occurs, something is lodged in the astral body that should have been grasped by the ego. It has strayed into the astral body, because man was not fully master of the impression. Say, a person looks at a caricature: perhaps he sees tiny little legs and an enormous head. What is he to make of it? He cannot quite master the impression; it is not what he generally sees in life. The impression slips down into the astral body—leaves the ego and enters the astral body. The person then tries to evoke a reaction from ether body and physical body. We have here, you see, a process that goes in the opposite direction. Something is present in the astral body, and the ether body wants to bring it down into the physical body. That is what laughter consists in. Something is being experienced in the astral body that the person cannot quite grasp; and laughter is the endeavour to show it up as foolish or ridiculous or the like by bringing it right down into the physical body.

To produce laughter on the stage we must first of all make sure of the right mood, and then try to hold it. Let us set down once more the vowels in their sequence, beginning this time with u, the vowel that is nearest the front of the mouth: u ü ö ä o i e a. Take the o, and go past the i to e: o e. Or take the ä, and go over to a: ä a. The latter gives the mood rather less clearly; it comes out very clearly in the o e: o e, o e, o e, o e. And now take the passage that is to make you laugh, and try to bring this mood into it. First listen, that is, to the speaker saying the words that are to provoke laughter, accompanying his words all the time with o e, o e; then break out into laughter, and your laughter will be the very best stage laughter that can be had. The mime is created out of the formed speech.

a e i o ä ö ü u

oe

äa

Suppose you want to reveal in your countenance that you are giving your whole attention. You let a passage be read out to you that is of a kind to demand close attention. As you listen, you gaze steadily before you, holding within you all the time the mood of a a a. Then you gradually carry this mood up into your eyes, as though you wanted your eyes too to say a. You press up into that fixed gaze of yours the feeling that you have in the uttering of a. Your face will then show just the right expression for attentiveness.

And now imagine another situation. Suppose an author has introduced into a comedy he is writing, an incident that did actually take place once in Austria. A party of people were met together in Reichenau and, being in a rather giddy mood, made up their minds to settle the question once and for all as to whether or no it were true, as some averred, that the editor of the Wiener Fremdenblatt, who was by the way a relative of the poet Heine, was a silly fool. They decided to send him an absurd telegram, and then to look in the paper next day to see whether he had been so stupid as to insert it, or just clever enough to take no notice of it. A little incident that would lend itself well as material for comedy! The telegram ran: The municipality of Reichenau has come to the decision to remove the Raxalp in order to give the resident Archduke an unimpeded view of the Styrian countryside. On the following day the telegram appeared word for word in the Wiener Fremdenblatt.1The Vienna Visitors' Gazette. Some of the party had wagered it would not appear; but others had been quite sure that Heine was stupid enough to accept it, and it was they of course who won the wager.

And now suppose this little story is read out to you. You will have good reason to be surprised when you hear how it ends. You will in that case open your eyes as wide as ever you can, and intone i i i; then stop and with that whole i-intonation concentrated in one powerful impression, let the feeling that it leaves in you steal up into your eyes: i. Sure enough, your countenance will have the right look; it will bear the expression of dumbfounded amazement.

Or again, let us say you are listening to a tale that is terrifying. Close your eyes, and intone u; stop, take the intoned u up into your eyes: u. Nothing could give your face the expression of terror so well as this. Carry the intonation of u into the closed eyes, and your whole countenance will bespeak terror. In this mime that results from u being pushed up into the closed eyes, you have a singularly good opportunity to observe how it is in the forming of the speech that you can call up the right play of countenance.

Many of our inner experiences are connected with something outside us. And so if we want, for instance, to express contempt for some person or object, it will be from a consonant that we shall learn the right mime. Have an appropriate passage read out to you and, as you listen, intone n n n n n n. When you have practised this sufficiently for the right play of feature to appear in your countenance, then you will be able to bring that mime into your speaking, so that when you speak the words of contempt you will speak them as they should be spoken. But you have always, let me say again, to start from speech; it all follows from a right forming of speech.

Suppose you want to express dejection. It is perfectly easy to learn, but it has to be learned. You have a passage read out that brings this mood to expression, and you intone the consonant w (v), combining with it as light a touch as possible of the e sound: w w w w . Then you fall silent, but remain in the gesture that is left in you by the experience; your gesture will be eloquent of despondency.

If you want to express rapture, then you must try to attain a pure out-breathing, as we have it in h. You could begin by saying the word Jehova. Then, gazing upwards and with arms also raised, let the ho become sheer out-breathing. There you have the gesture for rapture: arms reaching upwards, eyes also gazing upwards. (With many people you will find that even the lobes of the ears are lifted and the nostrils opened wide; one can, however, leave that to the unconscious.) And all the time you will be intoning h, doing your best to bring it at last to mere out-breathing, as pure as ever you can make it. So long as the h is in combination with the vowel, it is not yet pure. That is why I say, you have to make strenuous effort to attain it: Jehova, ho ho ... ho ... h ... You did not hear anything then, but I was doing it, the pure out-breathing And you will have noted the change that comes over the upward gaze as soon as ever one passes from the intoning with vowel accompaniment to the out-breathing pure and simple. That, then, is rapture.

Now for another mime and gesture that can also quite well be learned, and used always to be taught in the older schools of dramatic art. For we ought not to despise what was good in the earlier days; it has only to be evoked now in a new way; it has to be evoked out of speech—that is what is new about it. Imagine you intone a o, a o. While you intone, you contract your brow into vertical wrinkles and open your eyes as wide as ever you can: a o. And now drop the intoning, and you will have the right expression in mime and gesture for careful reflection and concern. This will only reveal itself fully when you have ceased intoning and carry in you the after-effect of the well-formed speech. But you must begin with the intoning, and then let the intoning pass over into your whole bearing and countenance.

I know well what the natural rejoinder will be to detailed advice of this kind: But if we have first to learn all this, whenever shall we come to the point of being ready for the stage? You will find, however, that all the methods I am advocating will, if properly carried out, prepare you for the stage in a shorter time than is taken by the training given in present-day schools of dramatic art. As a matter of fact, hardly any of those who appear on the stage have attended these schools; since, generally speaking, students who have been trained in them do not turn out to be the best actors, any more than the best painters or sculptors are to be found among those who have been professionally trained. For as a rule the methods used in art schools are rather uninspiring. Students who have real talent soon grow impatient and take themselves off to pursue art on their own account. But with regard to the exercises and so on that I have been recommending—once you begin to know them and study them, you will find they are not, after all, so alarmingly complicated.

And now I have something to say on more general lines in reference to a school of dramatic art. It is of great importance that an actor should have a good knowledge of eurhythmy. Not in order to perform it, for eurhythmy is an art that is performed on the stage on its own account. But to the full training of an actor, all the other arts have to make their contribution, and so too eurhythmy I do not mean that an actor should let his acting run on here and there into eurhythmy The result would be most inartistic. Eurhythmy can only be artistic when it is allowed to work in its own way—that is, to the accompaniment of recitation or of music. We must, you know, have a feeling for what it is in eurhythmy that makes it an art. Eurhythmy gives what cannot come to expression in music alone or in recitation alone; it takes these further, continues them. No one could feel it to be true eurhythmy if done to the accompaniment of singing. In singing, music has flowed over into speech. The eurhythmy would merely disturb the singing, and the singing the eurhythmy. Eurhythmy can be accompanied by recitation, which itself has nothing to do with bodily movement; for in recitation gesture has become inward. Eurhythmy can also be accompanied by instrumental music. But not by singing, if one wants to let eurhythmy work in a way that corresponds with its true ideal.

Not therefore directly, but indirectly eurhythmy can be of the very greatest significance for the actor. For what have we in eurhythmy 9 In eurhythmy we have the full, the macrocosmic gesture for vowel and consonant. I (arm stretched straight out); a still more intensely pointed i (fingers also stretched). And now try to continue inwards the feeling you have in making the eurhythmy for i. I do not mean merely the feeling of having one's arm and hand in that position; the i lies in the feeling that is experienced in the muscle. Try to hold this feeling fast, within you; let it be for you as though a sword were being thrust straight down into your body. And now, still continuing this feeling, try to intone i. Then the right nuance for your i will come to you from the eurhythmy; your i, as you speak it, will have the necessary purity. And it will be the same with the other vowels and consonants. Continue their eurhythmy inwards; fill yourself with the ghost of the eurhythmic form, with its mirrored reflection, and while still feeling the form there within you, intone. In this way you will come to speak your vowels and consonants in their purity. So much for an advice of a more general kind concerning your training.

If you will continue to keep all these things in mind, you will at length acquire a true understanding for what is essential in speech. For it is not enough for an actor to know his part. He must of course do that; but what matters above all is that he shall have the right thoughts and feelings concerning his calling. Otherwise he cannot really be an actor. No one can be an artist in any sphere who has not a true and worthy conception of the art he is following.

By entering with your whole heart into such a training as I have here been indicating, you will come to have a pure—let me say, a religious—understanding of what speaking really is; and not only of speaking, but also of the mime and gesture that are connected with it. And that is what is needed. For such a conception of speech will, more than anything else, give you a strong and clear feeling of the place of man in the universe. Gradually you will come to appreciate man's true dignity and worth, beholding how he stands at the very centre of the world-all.

Look at the animals. They too make sounds. Think of the lion's roar, of the lowing of the cow, or of the bleating of sheep and goat. The sounds uttered by these animals have the character of vowels. They are expressing what is within them—all the animals that lift up their voice in this manner. And then, as you go about Nature's world, you will also hear quite different forms of utterance, such as, for example, the sounds that are made by cicadas and other insects, where the sound is produced by the movements of certain limbs or organs. There you have sounds that show a decided consonantal character. And then at last you come to that wonderful development of sound that means so much to man—the song of the birds! In the singing of the birds you have music. So that while you hear vowels from the higher and consonants from the lower animals, the birds give you the possibility to hear music in the animal world.

But now what about that sound you hear when you go out into the country and listen to the cicadas or other insects? Go close up to one of them and watch it. Out of the question for you to have the impression that the cicada is wanting to say something to you with this consonantal sound that it produces ! You have before you the simple fact of an insect in action—that is all! And then what are we to say of the animals that low or bleat or roar? Such sounds do no more than express self-defence, or resistance, or again a sense of well-being; they are far from revealing any inner experience of soul. Finally, in the singing of the birds, you can distinctly feel that the music does not live inside them. The simple and natural feeling about the singing of the birds, you have when you compare the one or the other variety of it with the corresponding flight, with the beating of the wings. For it is true, there is a harmony between the external movements the bird makes in flight and the music it produces with its voice.

And now, turn right away from the animal world and listen to the inwardness, to the artistic forming of inner experience, that reaches you through the vowels as spoken by man! Listen again to the experience in and with the external world that reaches you through the consonants as spoken by man. Listen, I say, to human speech, listen to it also in its connection with mime and with gesture; and it will not fail to beget in you a right and true feeling for the significance of man in the universe. For verily it stands there revealed before you in what speech can become in man.

Then your heart and soul will receive the right orientation, and the way will lie open for you to enter further into the more esoteric aspect of our theme. And this is what we shall be doing in the remaining lectures.2The last sentence was greeted with enthusiastic applause. The course had been previously announced as ‘from the 5th to the 15th September ’.

11. Gebärde und Mimik aus der Sprachgestaltung heraus

Die Frage werden wir aufwerfen müssen: Wie wird sich, wenn Schauspielkunst, dramatische Darstellung wirklich in ein künstlerisches Leben einlaufen soll, dasjenige verhalten müssen, was der Schauspieler weiß und übt, beziehungsweise was die Bühne darstellt, zu dem, was durch diese kunstgemäße Gestaltung der Bühne, der Schauspielkunst dann in das Publikum als Verständnis der dramatischen Darstellungskunst übergehen kann? Es wird notwendig sein, daß vor allen Dingen jetzt noch einiges über Dinge gesagt wird, welche in die Schauspielschule werden aufzunehmen sein. Und das, was da in die Schauspielschule wird aufzunehmen sein, wird auch ein eindringliches Verständnis des Mimischen und einen Ausbau des Verständnisses für das Gebärdenhafte zu umfassen haben, wie wir schon im allgemeinen so etwas angedeutet haben. Erst dann, wenn sich dem Darsteller der Sinn eröffnet dafür, daß das alles sein muß, wird - ich will nicht sagen, um nicht ein philiströses Wort zu gebrauchen — das Publikum erzogen werden, denn eigentlich ist mir dieses Wort vom Erziehen zuwider, weil es keinen realen Inhalt hat, sondern ich will sagen, es wird das Publikum zum Verständnisse des Künstlerischen angeregt werden.

Gehen wir deshalb heute in sach- und fachgemäßer Weise einiges durch, was uns zum Verständnis zunächst des Mimischen und dann des Gebärdenhaften in einer noch eingehenderen Weise führen kann, als wir das schon getan haben.

Ich möchte auch da wiederum exempelhaft vorgehen. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel eine mimische Äußerung, welche eine deutliche Art des Mimischen nach sich ziehen muß, die sich auf die Emotion des Zornes bezieht. Zunächst kann man die Emotion des Zornes im Menschenwesen zu erfassen suchen. Der Zorn wirkt so, daß er zunächst die Muskeln anspannt, aber nach einiger Zeit zum Nachlassen zwingt. Man kann sagen, im Leben braucht einen nur der erste Teil dieser Zornesoffenbarung zu interessieren; aber wenn es sich um die künstlerische Darstellung handelt, müssen wir diese volle Offenbarung des Zornes haben, Anspannung und nachherige Erschlaffung.

Nun handelt es sich darum, wie man das Mimisch-Gebärdenhafte lernen soll, das sich auf solche Zornesäußerung beziehen kann. Und da wird es sich darum handeln, daß man, wenn man die Lautempfindungen entsprechend in sich ausgebildet hat, was das erste sein wird in der Schauspielschule, so wie ich das angedeutet habe, dann dazu überzugehen hat, irgendeine Stelle aus einem Drama, sagen wir also eine Zornpassage, rezitatorisch ablaufen zu lassen, und dabei - ich habe schon angedeutet, daß das für das Lernen am besten ist — mit dem Mimisch-Gebärdenhaften die Worte nicht gleich selbst verbindet, sondern einen Sprecher hat. Der Sprecher spricht schon so, wie zu sprechen ist; derjenige, der nun sich in das Mimisch-Gebärdenhafte hineinfinden soll, wird selbstverständlich genau den Inhalt der Worte verfolgen, aber ihn mit einer fortlaufenden i e-, i e-, i e-Empfindung begleiten, die er innerlich in sich ertönen läßt, während er zuhört. Und dazu wird er sich bemühen, dasjenige, was von selbst dadurch kommt, instinktiv, irgendwie in Armen oder Händen und mit der geballten Faust auszudrücken, die Muskeln anzuziehen, wieder erschlaffen zu lassen beim: i e, i e, i e. Das bedeutet, niemals anders als in Begleitung mit einer Lautempfindung irgend etwas physiologisch am Körper vorzunehmen, also nicht in bezug auf die Schauspielkunst anders zu üben, als dasjenige, was man am Körper vornimmt, in Begleitung einer Lautempfindung vorzunehmen.

Wenn man darstellen soll, daß Affekte: Angst, Gram, Schreck schon ihre Wirkung getan haben, wenn man also schon auftreten soll in dem Wirken von Schreck, Angst und dergleichen, dann wird der physiologische Tatbestand der sein, daß man von vornherein mit erschlafften Muskeln auftreten soll; aber die Art und Weise, wie man das zu üben hat, besteht darinnen, daß man das Erschlafftsein übt in Verbindung mit der e-Stimmung.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß bei allem Sorgenhaften - ob man ein Sorgenhaftes schon an sich trägt, also damit kommt, oder ob man in Sorge verfällt, während einem etwas gesagt wird - immer versucht werden muß, in der Sprachgestaltung leise ein ö anklingen zu lassen. Das heißt, man wird versuchen, bei all demjenigen, was sich auf Sorge bezieht, was sich darauf bezieht, daß man entweder mit der Sorge kommt, oder die Sorge sich auf einen legt, währenddem man die Rede des anderen hört, das Mimische dabei herauszubringen, indem man etwa in der ö-Stimmung die Hände und die Lider langsam sinken läßt. Nicht wahr, die Dinge müssen immer unter dem Aspekt betrachtet werden, daß sie noch freie Bahn für denjenigen lassen, der die Dinge durchnimmt. Ist der Affekt, in den man dadurch kommt, sehr stark, so wird man schließen da vorne - mit der Zunge nach oben, wenn man dann zu sprechen hat; beim weiteren Sprechen, wenn man Antwort gibt auf dasjenige, was der Partner sagt, mit womöglich zusammengepreßten Lippen das sagen. Und das gibt in der Tat ein wunderbares K.olorit. Der Zuschauer muß ohne weiteres instinktiv dann wenn zwei Unterredner auf der Bühne sind, der eine etwas sagt, was dem anderen Sorge oder Kummer macht, und der andere dann so antwortet, daß er selbst das z mit etwas gepreßten Lippen herausbringt - den richtig kolorierten Eindruck haben, wie das Gesagte auf den anderen, der antworten soll, hinüberwirkt.

Denn denken Sie nur - wollen wir einen extremen Fall nehmen - der eine sagt: Dein Bruder ist gestorben. — Der andere sagt: Ach, das zerschmettert mich! - Es kommt das Kolorit heraus durch die möglichst zusammengepreßten Lippen.

Findet man es nötig, das Mimische so weit auszudehnen, was natürlich bei einer ausgedehnten Sorge oder Angst der Fall sein wird, daß man sich blaß schminkt, so sollte man niemals ein blasses Geschminktsein anders begleiten als mit einer Rede, die durchaus mit mehr zusammengehaltenen Lippen, als das Normale ist, gesprochen wird. Niemals sollte man auf der Bühne mit blasser Schminke erscheinen, ohne zu gleicher Zeit in dieser Weise das Mimische zu gestalten.

Sehen Sie, besonders bedeutsam wird sein, daß der Schauspieler die richtige Beziehung von gewissen Dingen zum Leben ins Auge faßt. Es kann durchaus zum Mimisch-Gebärdenhaften kommen das Seufzen, das Stöhnen, aber es sollte niemals abstrakt für sich Seufzen und Stöhnen geübt werden, sondern immer im Anhören einer Stelle aus dem Dramatischen geübt werden, die zum Inhalte hat, daß man über sie hinwegkommen wird. Denn derjenige, der sich ganz vertieft in einen Schmerz, stöhnt nicht und seufzt nicht, sondern derjenige, der sich den Schmerz vom Halse schaffen will, der sich selbst verbessern will, stöhnt und seufzt. Das deckt sich mit dem Leben nicht immer ganz vollkommen; in der Kunst, im Stil, deckt es sich aber vollkommen. Da sollte Seufzen und Stöhnen nur verwendet werden, wenn es sich darum handelt, den Schmerz so weit zu erleichtern, daß man überhaupt sprechen kann, daß man nicht verstummt. Daher sollte schon, wenn man auf etwas zu antworten hat, was einen niederschmetternden Schmerz ausdrückt, ein schön gestaltetes Stöhnen und Seufzen vorangehen, durch das man sich gewissermaßen die Erlaubnis zum Sprechen erst erwirbt.

Dann wird es sich darum handeln, daß man auch im einzelnen übt so, daß der Körper physiologisch mitgeübt wird, aber immer in Anlehnung an das Sprachlich-Gestaltete. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel an, Sie hören einer traurigen Passage zu, hören dieser traurigen Passage so zu, daß Sie sich bemühen, das Gesicht gar nicht durch ein Mienenspiel zu ändern, aber Sie bewegen den Kopf dabei. Also: bewegter Kopf bei ruhigbleibendem Antlitze= Zuhören einer traurigen Passage.

Da tritt nämlich von selbst etwas ein, wenn Sie das tun. Da tritt das ein, daß Zwerchfell und auch dasjenige, was sich nach unten anschließt, in diejenige Bewegung kommen, in die sie kommen als Reaktion, als Gegenwirkung zu dem, was Sie mit dem Gesichte und mit dem Kopf tun. Und Sie üben Zwerchfell und Unterleib von selbst in der richtigen Weise. Das macht sich ganz von selber. Man sollte gar nicht anders als in Anlehnung an die Sprachgestaltung die Übung an dem Körper vornehmen. Also einer traurigen Passage zuhören: mit vollem Bewußtsein, mit ruhigem Antlitz und bewegtem Kopfe zuhören.

Hören Sie einer Passage zu, die Sie gleichgültig läßt, bewegen Sie den Kopf gar nicht, sondern starren Sie einfach mit möglichster Anteillosigkeit auf die gleichgültige Passage hin. Es ist nicht zuviel gesagt, weil es der Tatsache entspricht, wenn man darauf hinweist, daß solches Anhören mit ruhigem Gesichte, aber unbewegtem Kopf, so wie wenn man einschlafen wollte, eine ganz leise Absonderung bewirkt, die auch bei dem Phlegmatiker vorhanden ist, wenn er seinem Phlegma richtig folgt. Und man findet sich hinein auf die erste Art in die Darstellung des Melancholischen, auf die zweite Art in die Darstellung des Phlegmatischen.

Man kann also sagen: Wie bereitet sich der Schauspieler dazu vor, melancholische Charaktere darzustellen? Indem er traurigen Passagen zuhört, das Gesicht ruhig hält und den Kopf bewegt und sich dann dem überläßt, was in seinem Körper von selbst vorgeht.

Wie bereitet sich der Schauspieler dazu vor, phlegmatische Charaktere darzustellen? Indem er mit ruhigem Gesichte die Physiognomie des Einschlafens annimmt, also die Augenlider sinken läßt, die Nasenflügel sinken läßt, sich nicht bemüht, die Oberlippe durch den Willen zu bewegen; wenn er so zuhört und dadurch jene feine Absonderung hervorruft, welche die Begleitung des phlegmatischen Temperamentes ist. — Sie sehen in dem Ganzen den Geist des Arbeitens.

Wollen Sie die sanguinische Naive im ehemaligen Sinne —- ich sage es nur, um es anzudeuten, ich will diese Kategorie nicht wiederum konstruieren -, aber wollen Sie die sanguinische Naive vorbereiten, ja, dann machen Sie das so, daß Sie eine sensationelle Meldung, wie sie in einem Drama vorkommen kann, lesen lassen, und die Schauspielerin oder den Schauspieler —- es kann ja auch ein männlicher sanguinischer Naiver sein — während der Zeit recht starke Gesichtsbewegungen und auch Armbewegungen machen lassen. Das geht instinktiv in jenes sprudelnde Reden hinüber, das die Naiven zu entwickeln haben, diejenigen, die ein sanguinisches Temperament darstellen sollen.

Wollen Sie den Choleriker vorbereiten, das heißt denjenigen, der auf der Bühne Cholerisches darzustellen hat, dann wählen Sie dazu irgendeine Stelle, wo geschimpft wird. Sie finden da bei Shakespeare zahlreiche Stellen, die Sie gebrauchen können. Lassen Sie denjenigen, der das mimische Spiel einzuüben hat, dabei die Stirne runzeln, mit angezogenen Händen Fäuste bilden, und halten Sie ihn an, mit gespannten Muskeln bewußt sich auf den Boden zu stellen. Also: Stirne tunzeln, mit angehaltenen Händen Fäuste bilden, von den Knien nach abwärts durch die Waden die Muskeln spannen und bewußt in sich haben: Ich stehe mit der ganzen Fläche meines Fußes auf dem Boden auf. - Er wird dadurch geeignet werden, Cholerisches darzustellen.

Sehen Sie, so wie man Technisches haben muß, um eine andere Kunst zu lernen, so muß man auch bei der Schauspielkunst Technisches haben, das zu dem Richtigen führt. Zwei Dinge gibt es wenn man in den Büchern, die aus der gegenwärtigen Wissenschaft heraus geboren sind, nachliest, so findet man überall dabei das Wort: unerklärt -, zwei Dinge gibt es im Leben, welche die Wissenschaft heute auf diesem Gebiete, es gibt natürlich sehr viele, unerklärt läßt. Die Wissenschaft spricht überall von Grenzen des Erkennens, und sie hat mit Bezug auf das Erfassen der Sprache zwei deutliche Grenzen: es sind die Grenze vor dem Lachen und die Grenze vor dem Weinen. Die Wissenschaft registriert überall dazu: Lachen und Weinen, wie sie aus dem Menschen herauskommen, sind unerklärt.

Nun ist das aber nicht so. Nehmen wir zunächst das Weinen. Was bedeutet überhaupt das Weinen im Leben? Das Weinen geht immer daraus hervor, daß der Ätherleib des Menschen irgendwo zu stark den physischen Leib erfaßt. Wenn der Mensch dies in sich schmerzvoll fühlt, so wird er folgenden Prozeß durchmachen: physischer Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib, Ich - nun, der Ätherleib erfaßt irgendwo zu stark den physischen Leib. Man will die Kraft, die nach unten, nach dem physischen Leib geht, heraufholen nach dem Astralleib, ergießt in den Astralleib die Gegenkraft; der Ätherleib ist aber verbunden im Menschen mit dem flüssigen Elemente, und Sie haben ganz handgreiflich dasjenige, was da geschieht: der Ätherleib stößt nach dem astralischen Leib, und die physische Projektion davon ist das Ausstoßen der Tränen, das Weinen. Daher ist das Weinen auch eine Erleichterung für den Schmerz.

Versuchen Sie ein deutliches # anzuschlagen, immer mehr hineinzukommen in das Erleben des ö, dann bekommen Sie allmählich ein Mienenspiel, so daß Sie sich einfach von außen, von einer Tasse, kleine Wassertropfen hierher — an die Augen - zu setzen brauchen, und es ist Weinen. Es ist Weinen! Es braucht gar nicht von innen zu kommen. Wenn Sie ganz in das Mienenspiel übergehen, immer mehr bewußt werden, was Ihre Nase, was Ihre Augen tun, wenn Sie d sagen, nehmen dann aus einer Tasse Wassertropfen, setzen sich sie auf: Sie weinen. Es ist vollständig dargestellt.

Damit haben Sie aber auch gegeben, was das Wichtige ist. Es handelt sich auf der Bühne nicht darum, daß sentimentale Zuschauer sagen können, was ich immer wieder und wieder gehört habe von der Duse aber es war nicht wahr -: Sie hat wirklich geweint. — Sie hat wirklich geweint, das ist dasjenige, was einem die Begeisterung für einen wirklichen Erfolg dann immer ausdrücken soll. Wie auch der Duse gegenüber es immer wieder betont worden ist, daß sie auf der Bühne tatsächlich erröten konnte, sie, die eine ganz blasse Hautfarbe natürlich hatte. Scheinbar konnte sie erröten. Die Leute haben nur nicht bemerkt, daß sie sich dabei umgedreht hat, daß sie auf der einen Seite hell, auf der anderen Seite dunkler geschminkt war. Aber es ist nicht ganz würdig, derleiDinge, die ja eine starke Illusion schon hervorrufen können, wirklich auch anzunehmen. Diese Dinge sollten eigentlich - eingeschult durch solche Schulung, wie sie jetzt ausgearbeitet wird durch ein vollständig Sich-Überlassen dem ö-Laute - herbeigeführt werden.

Nun, sehen Sie, wenn wir in derselben Weise das Lachen betrachten, dann bekommen wir die Sache so: Beim Lachen sitzt etwas im astralischen Leibe. Es verirrt sich etwas, was wir mit dem Ich auffassen sollen, in den astralischen Leib hinein, weil wir nicht ganz mächtig sind des Eindrucks. Wenn einer eine Karikatur anschaut: kleine winzige Beine, einen riesigen Kopf — man ist nicht ganz mächtig des Eindrucks. Was soll man damit anfangen? Im Leben sieht man das nicht. Es rutscht zum astralischen Leib hinunter, geht vom Ich zum astralischen Leib hinein. Nun versucht man die Reaktion des Ätherleibs und physischen Leibs hervorzurufen. Es ist ein entgegengesetzter Gang. Das, was im astralischen Leib ist, will der Ätherleib in den physischen Leib hineinbringen: es ist das Lachen. Das Lachen ist die Bemühung, ein astral Erlebtes, nicht ganz Erfaßtes, dadurch als etwas Törichtes oder dergleichen hinzustellen, daß man es bis in den physischen Leib hinunterbringt. Das erreichen Sie dadurch, daß Sie versuchen, eine solche Stimmung festzuhalten.

Schreiben wir uns noch einmal die Reihenfolge der Vokale auf. Fangen wir beim u an, dem vordersten: u ü ö ä o i e a. Nehmen Sie das o, gehen Sie über das i hinüber zum e: o e. Oder nehmen Sie das ä und gehen Sie zu dem a hinüber: ä a, das weniger deutlich ist. Besonders deutlich ist das o e, o e, o e, o e, o e - und versuchen Sie, aus dieser Stimmung herauszubringen dasjenige, was in das Lachen hineingehen soll; das heißt, hören Sie sich von dem Sprecher eine zum Lachen bringende Passage an und begleiten Sie sie zuerst mit o e, o e und gehen Sie dann in das Lachen über, und Ihr Lachen wird das schönste Bühnenlachen, das Sie haben können. Auf diese Weise wird eben aus der Sprachgestaltung heraus das Mimische geschaffen.

Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben nötig, für irgend etwas im Mienenspiel Aufmerksamkeit zu offenbaren. Sie erreichen das, indem Sie sich irgend etwas vorlesen lassen, was dazu bestimmt ist, daß man aufmerkt. Sie bemühen sich, den Blick zu fixieren, aber die Stimmung des a a a dabei zu haben, so daß Sie allmählich diese Stimmung wie in den Blick hineinleiten, wie wenn Sie mit den Augen sagen wollten: a. Sie drängen das Gefühl, das Sie haben, im a-Aussprechen, etwas hinauf in den fixierten Blick hinein: a. Sie bekommen das mimische Spiel des Aufmerkens.

Nehmen Sie an, Sie lassen sich von jemandem vorlesen - nun, sagen wir, es würde ein Lustspieldichter in sein Stück eine kleine Szene hineinbringen, die sich einmal in Österreich abgespielt hat, wo eine Gesellschaft in Reichenau gesessen hat und aus einer gewissen lustigen Stimmung heraus dort den Nachweis bringen wollte, daß der Redakteur des «Wiener Fremdenblattes», der noch dazu ein Verwandter von Heine war, ein ganz großer Dummkopf sei. Da beschloß diese Gesellschaft in Reichenau, folgendes Telegramm aufzusetzen, um dann am nächsten Tage zu sehen, ob der Heine so dumm sei, dieses Telegramm aufzunehmen, oder so gescheit noch, daß er es nicht aufnähme. Das könnte man ja ganz gut in ein Lustspiel umarbeiten. Das Telegramm lautete: Die Gemeinde Reichenau hat beschlossen, die Raxalp abzutragen, damit der Erzherzog - der immer dort wohnte - einen freien Ausblick in die grüne Steiermark hat. - Am nächsten Tag erschien das Telegramm wörtlich im «Wiener Fremdenblatt». Einige hatten gewettet, daß er es nicht tun werde; aber diejenigen, die gesagt haben, der Heine ist so dumm, daß er auch das aufnehmen wird, haben mit ihrer Wette gesiegt.

Aber nehmen wir einmal an, diese Passage würde vorgelesen. Man hat ein Recht, wenn man den Erfolg hört, überrascht zu sein. Man macht in diesem Falle das Auge so weit auf, als es einem gelingt, beginnt mit der i-Intonierung: i i i, läßt sie wieder aufhören und läßt dasjenige, was man in der z-Intonierung fühlt, in diesem merkwürdigen Zusammenballen der ganzen z-Intonierung, hinaufrutschen in das Auge: i. Sie werden sehen, daß Sie den Blick herauskriegen.

Weiter: das ganze Antlitz, meine lieben Freunde, bekommt den Ausdruck des Erschreckens, wenn Sie einer Erzählung zuhören, durch die man erschrecken kann, die Augen zumachen, u intonieren, aufhören, das intonierte u in die Augen hineinnehmen: u = es wird Erschrecken, mehr als irgend etwas anderes, es wird Erschrecken. Die Intonation des u in das geschlossene Auge hineinnehmen: das ganze Antlitz bekommt den Ausdruck des Erschreckens. Gerade an dieser Gebätrde, an dieser Gesichtsmimik des #, welches in das geschlossene Auge hinaufgeschoben wird, sieht man, wie man an der Sprachgestaltung das Mienenspiel heranziehen kann.

Manche inneren Erlebnisse beziehen sich dann auf Äußeres. So, wenn man ausdrücken will Verachtung von etwas, was sich auf Äußeres bezieht, muß ja konsonantisiert werden, wie ich gesagt habe. Lassen Sie sich eine Passage vorlesen, intonieren Sie: n und machen Sie die verachtende Gebärde, Sie begleiten das mit n n n n. Wenn Sie sich genügend eingeübt haben, was diese Gebärde auf Ihrem Antlitz erscheinen läßt, dann werden Sie das auch sprechen können, wenn Sie in dem Satze das Verachtende zu sprechen haben, dann werden Sie es in der richtigen Weise sprechen können. Aber alles, wie gesagt, aus der Sprachgestaltung herausholen.

Nehmen wir an, jemand will Niedergeschlagenheit ausdrücken. Es ist eigentlich sehr leicht zu lernen, aber man muß es eben lernen. Man läßt sich eine Stelle vorlesen, die Niedergeschlagenheit ausdrückt, und intoniert, höchstens nur mit Anklingenlassen des e, diesen Konsonanten: w w w w w. Dann verstummen Sie, aber bleiben in der Gebärde: Sie haben die Niedergeschlagenheit in der Gebärde. - Wollen Sie Entzücken ausdrücken, so versuchen Sie, einen reinen Aushauch zu bekommen, wie er beim Aushauch des h da ist; wie etwa, wenn wir beginnen damit, das Wort Jehova zu sagen; ho übergehen lassen in den reinen Aushauch, dabei Blick nach oben gewendet, Arme nach oben gewendet: Sie bekommen die Gebärde des Entzücktseins. Arme nach oben gewendet, Blick nach oben gewendet — bei manchem wenden sich dann noch die Ohrläppchen nach oben, bei manchem reißen sich die Nasenflügel auf, das kann man aber dem Unbewußten überlassen, und dabei eben dieses h intonieren, möglichst rein sich herausarbeiten, daß man das erst bekommt. Solange man das A in Verknüpfung noch hat mit einem Vokal, ist es eben nicht rein, deshalb sage ich, man arbeite heraus: Jehova, ho, ho ... h... h... Sie hören es gar nicht, aber ich mache es, und Sie sehen, daß sofort der Blick verändert wird, wenn man übergeht vom Begleiten - vokalischen Begleiten, Intonieren — zu dem bloßen Aushauchen. Das gibt das Entzücken.

Nun etwas, was man gut lernen kann und was auch immer gelernt worden ist, aber dasjenige, was gut war in der alten Kunst, darf deshalb nicht verachtet werden, es muß nur wiederum herausgeholt werden aus der Sprachgestaltung, und das ist das Neue daran. Nehmen Sie an, Sie intonieren a u, a u, aber bemühen sich, während Sie a u intonieren, die Falten der Stirne senkrecht zu machen, die Augen aufzumachen, so weit Sie können: a. Jetzt lassen Sie weg die Intonierung a: Sie haben die Gebärde des Nachdenkens, des sorgenvollen Nachdenkens im vollen Sinne des Wortes. Sie tritt eben erst dann ein, wenn die Sprachgestaltung nachwirkt, wenn man mit dem Intonieren aufhört, aber man muß mit dem Intonieren anfangen, dann übergehen lassen das Intonieren in die Haltung.

Ich weiß, daß solche Dinge natürlich zunächst so bedacht werden, daß man sagt: Ja, wann kommt man denn dann zum Bühnenspiel? Aber Sie werden sehen, all das, was da gefordert wird, kann, wenn es gerade sachgemäß gemacht wird, eigentlich in einer kürzeren Zeit gemacht werden, als man die Dinge in den gegenwärtigen Schauspielschulen besorgt, die nur nicht besucht werden von denen, die dann auftreten, weil gewöhnlich das nicht die besten Schauspieler werden, die in den gegenwärtigen Schauspielschulen ausgebildet werden, ebensowenig wie in Malschulen oder Bildhauerschulen die besten Maler oder Bildhauer ausgebildet werden, denn in der Regel ist es ziemlich talentlos, wie dort die Dinge geübt werden. Die übrigen fahren vorher aus der Haut, um im weiteren die Kunst zu üben. Nun ja, die Dinge werden nicht so furchtbar kompliziert sein, sie müssen nur erst gewußt und studiert sein!

Nun möchte ich etwas sagen, was mehr generell ist, aber von einer großen Wichtigkeit und Bedeutung ist. Der Schauspieler sollte schon das Eurythmische kennen, nicht um zu eurythmisieren, denn Eurythmie ist eine Kunst, die für sich auf der Bühne ausgeübt wird. Aber so wie der Schauspieler Anklänge haben soll in seinem Studium an alle anderen Künste, so auch an die Kunst der Eurythmie. Er sollte gerade das Eurythmische anders anwenden, als indem er etwa versucht, dasjenige, was er zu leisten hat, im einzelnen ins Eurythmische auslaufen zu lassen. Da wird denn doch nichts Künstlerisches daraus. Eurythmie muß für sich wirken, wenn sie künstlerisch sein soll, kann nicht anders wirken, als indem sie von Rezitation und Musik begleitet wird und eben bewegte Sprache ist. Man muß schon empfinden bei der Eurythmie, was das Künstlerische an der Eurythmie ist, nämlich gerade dasjenige, was nicht ausgedrückt werden kann im Musikalischen selber oder im Rezitatorischen selber, was von da aus dann weiterlaufen muß. Daher wird niemand es als richtig eurythmisch ansehen können, wenn einer singt, der andere eurythmisiert. Im Singen haben wir schon das Musikalische in das Sprachliche hinübergeleitet, und es stört nur die Eurythmie das Singen und das Singen die Eurythmie. Begleitet werden kann die Eurythmie von dem Rezitatorischen, das wiederum weit weg liegt von dem körperlich Bewegten, verinnerlichte Gebärde ist, und von dem Instrumental-Musikalischen; nicht aber vom Gesang, wenn man im idealen Sinne Eurythmie wirken lassen soll.

Aber für den Schauspieler kann die Eurythmie indirekt von größter Bedeutung sein. Denn was ist denn in der Eurythmie erreicht? In der Eurythmie ist erreicht, daß die vollkommenste, die makrokosmische Gebärde für den Vokal und für den Konsonanten da ist; i = Arme strecken, ein besonders spitzes i = gestreckte Finger dazu. Jetzt versuchen Sie einmal dasjenige, was Sie fühlen - denn das : liegt nicht darin, daß man die Hand ausstreckt, sondern das i liegt in dem, was der Muskel fühlt -, versuchen Sie dieses Gefühl ins Innere fortzusetzen, stark im Inneren festzuhalten, versuchen Sie, wie wenn Ihnen etwas wie ein Schwert von da aus in den Leib dringen würde, versuchen Sie jetzt i zu intonieren mit dieser Empfindung, daß sich das da fortsetzt: i — dann bekommen Sie rückwirkend gerade die Nuance für das i heraus, welche die reinste ist, die Sie zu sprechen haben. Ebenso für die anderen Vokale und Konsonanten. Wenn Sie sie nach dem Inneren fortsetzen, gewissermaßen sich ausfüllen mit dem Gespenst der eurythmischen Gestaltung nach innen, mit diesem Spiegelbild, mit diesem Gegenbild, und dabei intonieren, dann werden Sie Ihre Vokale und Ihre Konsonanten rein haben, so wie Sie sie brauchen. Das ist etwas Generelles.

Sehen Sie, wenn Sie dies alles ins Auge fassen, so werden Sie zuletzt ein wirkliches Verständnis vom Wesenhaften der Sprache gewinnen. Und darum handelt es sich, daß der Schauspieler nicht nur seine Rolle kennt - die soll er kennen -, aber daß er mit der richtigen Gesinnung in seinem Berufe darinnensteht. Ohne das kann man eigentlich nicht Schauspieler, wie überhaupt nicht Künstler sein, ohne das richtige, gesinnungsmäßig richtige Datinnenstehen in seinem Berufe zu haben.

Dadurch aber, daß man in einer solchen Schulung lebt, wie die angedeutete ist, kommt man zu einer reinen, ich möchte sagen, religiösen Auffassung des Sprechens und des damit verbundenen Mimischen und Gebärdenspieles. Und diese Auffassung ist es, die man braucht. Denn man kann durch diese Auffassung die Stellung des Menschen im Weltenall wirklich intensiver empfinden als durch etwas anderes. Man kommt allmählich dadurch in eine Empfindung von der Würde des Menschen im Weltenall, in eine Empfindung von der ganzen zentralen Stellung des Menschen im Weltenall hinein. Denn man wird gewahr, auch Tiere haben Stimme; man braucht sich nur zu erinnern an das Brüllen des Löwen, das Muhen der Kuh, das Meckern der Schafe, der Ziegen und so weiter. Es ist mehr vokalisierend. Die Tiere drücken ihr Inneres aus, die Tiere, welche auf diese Weise die Stimme erheben. Aber Sie können auch hinausgehen in die Natur und jene verschiedenen Stimmentwickelungen hören, welche in ausgesprochenem Maße dutch Zikaden und so weiter, durch verschiedene Tiere in der Bewegung der Glieder hervorgerufen werden; Sie haben da ein ausgesprochenes Konsonantisieren.

Und gehen Sie dann über zu dem, was am meisten an den Menschen herandringt, zu der Stimmentwickelung der Vögel. Sie haben die Möglichkeit da, das Musikalische auf der einen Seite bei den Vögeln zu sehen, auf der anderen das Vokalisierende bei den höheren Tieren, das Konsonantisierende bei den niederen Tieren. Aber sehen Sie, wenn Sie hinausgehen und ein Insekt, die Zikade oder irgendein anderes Insekt, durch die Bewegung der Glieder einen Ton hervorbringend haben: Sie gehen an das Insekt heran. Sie können unmöglich bei diesem Konsonantisieren, beim Anblick des Insektes den Eindruck haben, das will Ihnen etwas sagen. Sie bleiben stehen bei der Auffassung einer Tatsache, die im 'Tun liegt. Sie gehen zu denjenigen Tieren, die muhen oder meckern oder brüllen. Wiederum haben Sie die Auffassung nicht, daß das über Abwehr, über Wohlgefühl hinaus zu einem inneren Erleben kommt. Es geht nicht ins Innere. Sie haben bei der Stimmentwickelung der Vögel das deutliche Gefühl: das Musikalische lebt nicht in ihnen. Ja, Sie haben noch die natürlichste Empfindung gegenüber der Stimme der Vögel, wenn Sie mit irgendeiner Stimmgestaltung der Vögel vergleichen den Flug, die Bewegung der Flügel, es ergibt sich ein harmonischer Einklang zwischen der Außenbewegung, dem, was der Vogel außen macht, und demjenigen, was er als Stimme entwickelt. Wenn Sie das alles durchgehen und dann die gestaltete Verinnerlichung im menschlichen Vokalisieren finden und das gestaltete Miterleben der Außenwelt im menschlichen Konsonantisieren, und das alles im Zusammenhange mit Gebärde und Mimik, dann bekommen Sie dadurch ein rechtes Gefühl von demjenigen, was der Mensch im Weltenall bedeutet, dadurch daß bei ihm gerade die Sprachgestaltung so werden kann.

Dadurch kommt aber eine bestimmte Einstellung, wie man mit einem sehr schönen Worte, weil man überall deutsch sein will heute, gesagt hat, es kommt eine Orientierung des ganzen Gemütes zustande.

Wie man zu dieser Orientierung beitragen kann, das wird dann noch in den nächsten Stunden als eine mehr esoterische Seite der Sache zur Betrachtung kommen.

11. Gestures and Facial Expressions Derived from Speech Formation

We will have to ask the question: if acting and dramatic performance are really to become part of an artistic life, how should what the actor knows and practices, or what is presented on stage, relate to what can be conveyed to the audience as an understanding of the dramatic art of performance through this artistic design of the stage and the art of acting? Above all, it will be necessary to say a few things about what needs to be included in drama school. And what needs to be included in drama school will also have to encompass a profound understanding of facial expressions and a development of understanding for gestures, as we have already indicated in general terms. Only when the performer realizes that all this is necessary will the audience be educated—I don't want to use a philistine word—because I actually dislike the word “educate” because it has no real content, but I want to say that the audience will be stimulated to understand the artistic.

Let us therefore go through some things today in a factual and professional manner that can lead us to an even deeper understanding of mimicry and then of gestures than we have already done.

I would like to proceed by way of example again. Let us take, for example, a facial expression that must entail a distinct type of facial expression relating to the emotion of anger. First, we can try to grasp the emotion of anger in human beings. Anger works in such a way that it first tenses the muscles, but after a while forces them to relax. One could say that in life, only the first part of this manifestation of anger is of interest; but when it comes to artistic representation, we must have this full manifestation of anger, tension and subsequent relaxation.

Now the question is how to learn the facial expressions and gestures that can relate to such an expression of anger. And here it will be a matter of developing the appropriate sound sensations within oneself, which will be the first thing in drama school, as I have indicated, and then moving on to reciting a passage from a drama, say a passage expressing anger, and in doing so — I have already indicated that this is best for learning — not immediately connect the words with the mimic gestures and gestures themselves, but have a speaker. The speaker already speaks in the way that is to be spoken; the person who is now to find their way into the mimic gestures and gestures will, of course, follow the exact content of the words, but accompany it with a continuous i e-, i e-, i e-sensation, which he allows to resound within himself while he listens. And to this end, he will endeavor to express what comes naturally through this, instinctively, somehow in his arms or hands and with his clenched fist, tensing his muscles and then relaxing them again with: i e, i e, i e. This means never doing anything physiologically to the body other than in accompaniment with a sound sensation, i.e., not practicing acting in any other way than doing what one does to the body in accompaniment with a sound sensation.

If one is to portray that emotions such as fear, grief, and shock have already had their effect, so that one is already to appear in the effect of shock, fear, and the like, then the physiological fact will be that one has already done something to the body from the outset. fear, grief, fright have already had their effect, if one is to appear in the throes of fright, fear, and the like, then the physiological fact will be that one should appear with relaxed muscles from the outset; but the way to practice this is to practice relaxation in connection with the e-mood.

Now, the point is that in all matters of concern – whether one already carries a concern within oneself, i.e., comes with it, or whether one falls into concern while something is being said to one – one must always try to let an ö sound softly in one's speech formation. This means that in all matters relating to worry, whether you come with the worry or the worry falls upon you while you are listening to the other person speak, you should try to bring out the mimicry by slowly lowering your hands and eyelids in the e-vibration. Isn't it true that things must always be considered from the perspective that they still leave room for the person who is processing them? If the emotion that this evokes is very strong, then you will conclude at the front—with your tongue up when you have to speak; when you continue speaking, when you respond to what your partner is saying, say it with your lips pressed together if possible. And that does indeed create a wonderful atmosphere. When two people are talking on stage, one says something that causes the other concern or grief, and the other responds with slightly pressed lips, the audience must instinctively have the correct impression of how what has been said affects the other person who is to respond.

Just think—let's take an extreme case—one says: Your brother has died. — The other says: Oh, that devastates me! — The color comes out through the lips pressed together as tightly as possible.

If it is necessary to extend the facial expression to such an extent, which will of course be the case with prolonged worry or fear, that one applies pale makeup, one should never accompany pale makeup with anything other than speech that is spoken with lips pressed together more than is normal. One should never appear on stage with pale makeup without at the same time shaping the facial expression in this way.

You see, it will be particularly important for the actor to consider the correct relationship of certain things to life. Sighing and groaning may well become part of the facial expressions and gestures, but they should never be practiced in the abstract, but always in conjunction with listening to a passage from the drama that has the content that one will get over it. For those who are completely immersed in pain do not groan and sigh, but those who want to get rid of the pain, who want to improve themselves, groan and sigh. This does not always correspond perfectly with life, but in art and style it corresponds perfectly. Sighing and groaning should only be used when it is a matter of alleviating the pain to such an extent that one can speak at all, that one does not fall silent. Therefore, when one has to respond to something that expresses devastating pain, it should be preceded by a beautifully crafted groan and sigh, through which one acquires, as it were, the permission to speak.

Then it will be a matter of practicing in detail so that the body is also physiologically trained, but always in accordance with the linguistic form. Suppose, for example, you are listening to a sad passage, listening to this sad passage in such a way that you try not to change your facial expression at all, but you move your head. So: moving head with a still face = listening to a sad passage.

When you do this, something happens automatically. The diaphragm and everything below it begin to move in response to what you are doing with your face and head. And you exercise your diaphragm and abdomen in the right way all by yourself. It happens all by itself. You should not do the exercise on your body in any other way than in accordance with speech formation. So listen to a sad passage: listen with full awareness, with a calm face and a moving head.

Listen to a passage that leaves you indifferent, do not move your head at all, but simply stare at the indifferent passage with as much indifference as possible. It is no exaggeration to say that listening in this way, with a calm face but an unmoving head, as if you were trying to fall asleep, causes a very quiet separation, which is also present in the phlegmatic person when they follow their phlegm correctly. And one finds oneself in the first way in the portrayal of the melancholic, in the second way in the portrayal of the phlegmatic.

So one can say: How does the actor prepare to portray melancholic characters? By listening to sad passages, keeping his face calm and moving his head, and then surrendering to what happens naturally in his body.

How does the actor prepare to portray phlegmatic characters? By calmly assuming the physiognomy of falling asleep, i.e., letting his eyelids droop, letting his nostrils droop, not trying to move his upper lip by will; when he listens like this and thereby evokes that subtle secretion that accompanies the phlegmatic temperament. — You see the spirit of work in the whole thing.

Do you want the sanguine naive in the former sense — I only say this to hint at it, I don't want to construct this category again — but if you want to prepare the sanguine naive, then do so by having them read a sensational message, such as might occur in a drama, and have the actress or actor — it can also be a male sanguine naive — make quite strong facial movements and arm movements during this time. This instinctively leads to the effervescent speech that the naive characters have to develop, those who are supposed to represent a sanguine temperament.

If you want to prepare the choleric character, that is, the one who has to portray choleric behavior on stage, then choose any passage where someone is ranting and raving. You will find numerous passages in Shakespeare that you can use. Have the person who has to practice the miming frown, clench their fists with their hands drawn in, and instruct them to stand on the floor with their muscles tensed. So: frown, clench your fists with your hands drawn in, tense the muscles from your knees down through your calves, and consciously keep in mind: I am standing with the entire surface of my foot on the floor. - This will enable them to portray a choleric character.

You see, just as you need technical skills to learn another art, you also need technical skills in the art of acting that lead to the right result. There are two things that, when you read the books that have emerged from current science, you will find the word “unexplained” everywhere. There are two things in life that science today leaves unexplained in this field, although there are of course many others. Science speaks everywhere of the limits of knowledge, and it has two clear limits with regard to the understanding of language: the limit before laughter and the limit before crying. Science records everywhere that laughter and crying, as they come out of human beings, are unexplained.

But that is not the case. Let us take crying first. What does crying mean in life? Crying always arises from the etheric body of the human being grasping the physical body too strongly somewhere. When a person feels this painfully within themselves, they go through the following process: physical body, etheric body, astral body, ego – now, the etheric body grips the physical body too strongly somewhere. One wants to bring the force that goes down to the physical body up to the astral body, pouring the counterforce into the astral body; but the etheric body is connected in the human being with the fluid element, and you have quite tangibly what happens there: the etheric body pushes toward the astral body, and the physical projection of this is the shedding of tears, crying. Therefore, crying is also a relief for the pain.

Try to strike a clear #, to get more and more into the experience of the ö, then you will gradually get a facial expression so that you simply need to put small drops of water here — on your eyes — from outside, from a cup, and it is crying. It is crying! It does not have to come from within. When you become completely absorbed in the facial expression, becoming more and more aware of what your nose and your eyes are doing when you say “d,” then take drops of water from a cup and place them on your eyes: you are crying. It is completely portrayed.

But in doing so, you have also conveyed what is important. On stage, it is not about sentimental audience members being able to say what I have heard over and over again about Duse, but it was not true—she really cried. She really cried, and that is what enthusiasm for real success should always express. As has been emphasized time and again with regard to Duse, she was actually able to blush on stage, she who naturally had very pale skin. Apparently, she was able to blush. People just didn't notice that she turned around, that she was wearing light makeup on one side and darker makeup on the other. But it is not entirely dignified to really accept such things, which can already create a strong illusion. These things should actually be brought about through training, such as is now being developed through complete surrender to the ö sound.

Now, you see, if we look at laughter in the same way, we get the following picture: when we laugh, something sits in the astral body. Something that we should perceive with the ego strays into the astral body because we are not quite powerful enough to make the impression. When someone looks at a caricature: tiny little legs, a huge head — one is not quite powerful enough to make an impression. What should one do with it? One does not see this in life. It slips down to the astral body, goes from the ego into the astral body. Now one tries to evoke the reaction of the etheric body and the physical body. It is an opposite process. What is in the astral body, the etheric body wants to bring into the physical body: it is laughter. Laughter is the effort to present an astral experience, not fully grasped, as something foolish or similar, by bringing it down into the physical body. You achieve this by trying to hold on to such a mood.

Let us write down the sequence of vowels again. Let us start with u, the first one: u ü ö ä o i e a. Take o, move across i to e: o e. Or take ä and move across to a: ä a, which is less distinct. The o e, o e, o e, o e, o e is particularly clear – and try to bring out of this mood what should go into the laughter; that is, listen to a passage from the speaker that makes you laugh and accompany it first with o e, o e and then move on to laughter, and your laughter will be the most beautiful stage laughter you can have. In this way, facial expressions are created from the speech formation.

Suppose you need to show attention to something in your facial expressions. You can achieve this by having someone read something to you that is intended to attract attention. You try to fix your gaze, but keep the mood of the a a a with you, so that you gradually guide this mood into your gaze, as if you wanted to say with your eyes: a. You push the feeling you have in the pronunciation of a up into your fixed gaze: a. You get the facial expression of paying attention.

Suppose you let someone read to you—well, let's say a comedy writer included a little scene in his play that once took place in Austria, where a group of people were sitting in Reichenau and, in a certain humorous mood, wanted to prove that the editor of the Wiener Fremdenblatt, who was also a relative of Heine, was a complete fool. So this society in Reichenau decided to write the following telegram to see the next day whether Heine was stupid enough to publish it or smart enough not to. That could easily be turned into a comedy. The telegram read: The municipality of Reichenau has decided to remove the Raxalp so that the Archduke, who always lived there, has an unobstructed view of the green Styria. The next day, the telegram appeared verbatim in the Wiener Fremdenblatt. Some had bet that he would not do it, but those who said that Heine was so stupid that he would accept it won their bet.

But let's assume that this passage was read aloud. One has a right to be surprised when one hears the result. In this case, you open your eyes as wide as you can, begin with the i intonation: i i i, let it stop again and let what you feel in the z intonation, in this strange accumulation of the whole z intonation, slide up into your eyes: i. You will see that you get the look out of it.

Next: the whole face, my dear friends, takes on an expression of terror when you listen to a story that can frighten you, close your eyes, intonate u, stop, take the intoned u into your eyes: u = it will be terror, more than anything else, it will be terror. Take in the intonation of the u into the closed eye: the whole face takes on an expression of horror. It is precisely in this gesture, in this facial expression of the #, which is pushed up into the closed eye, that one can see how speech formation can be used to influence facial expressions.

Some inner experiences then relate to the outer world. So, if you want to express contempt for something that relates to the outer world, you have to consonantize, as I said. Have someone read a passage to you, intonate: n and make the contemptuous gesture, accompanying it with n n n n. Once you have practiced enough to make this gesture appear on your face, you will also be able to speak it when you have to express contempt in the sentence, and you will be able to speak it in the right way. But, as I said, everything comes from speech formation.

Let's assume that someone wants to express despondency. It is actually very easy to learn, but you have to learn it. You have someone read you a passage that expresses despondency, and you intonate, at most only with a hint of the e, this consonant: w w w w w. Then you fall silent, but remain in the gesture: you have the despondency in the gesture. If you want to express delight, try to produce a pure exhalation, as in the exhalation of the h; for example, when we begin to say the word Jehovah; let the ho pass into a pure exhalation, while looking upward and turning your arms upward: you will get the gesture of delight. Arms turned upward, gaze turned upward—for some, the earlobes then turn upward, for others, the nostrils flare, but you can leave that to the unconscious, and just intone this h, working it out as purely as possible, so that you get that first. As long as you still have the A in combination with a vowel, it is not pure, That is why I say, work it out: Jehovah, ho, ho ... h... h... You don't hear it at all, but I do it, and you see that the gaze changes immediately when you move from accompanying — vocal accompaniment, intonation — to mere exhalation. That is what gives delight.

Now something that can be learned well and that has always been learned, but what was good in the old art should not be despised for that reason; it just has to be brought out again from speech formation, and that is what is new about it. Suppose you intonate a u, a u, but while you are intoning a u, you try to make the wrinkles on your forehead vertical and open your eyes as wide as you can: a. Now leave out the intonation a: you have the gesture of thinking, of thoughtful reflection in the full sense of the word. It only occurs when speech formation has had an effect, when you stop intoning, but you have to start with intoning and then let the intoning transition into the posture.

I know that such things are naturally considered at first in such a way that one says: Yes, but when does one get to stage acting? But you will see that everything that is required can, if done properly, actually be done in less time than it takes in the current acting schools, which are not attended by those who then perform, because usually the best actors are not trained in the current acting schools, just as the best painters or sculptors are not trained in art schools or sculpture schools, because as a rule the way things are practiced there is rather talentless. The rest go out of their way to practice the art further. Well, things will not be so terribly complicated, they just have to be known and studied first!