Speech and Drama

GA 282

21 September 1924, Dornach

XVII. Further Study of the Sounds of Speech

My dear Friends,

In times past when men had a more intense, but of course still instinctive, feeling of what it is in man that reveals itself in his speaking, they were aware of the process that does actually take place in the forming of speech, a process that consists in the astral body laying hold—quite simply—of the etheric. today we speak and talk, knowing no more of what is going on within us at the time than we do in regard to any other of our actions; for of the complicated inner processes that accompany all human activities we are quite unaware. And it is of course only right that we do not watch our actions too closely while we are doing them, or they would lose their spontaneity. But one who sets out to be an artist in the forming of speech and in the use of mime and gesture must learn to recognise how astral body and ether body have here found their way into an independent co-operation; at any rate, during the time of his training the reality of this should be constantly present to his consciousness. The artist must have felt—I do not say he must have seen, but he must have experienced in feeling what it means when we say that through the working together of astral body and ether body a second man has been begotten within us, has been set free within us, and lives in speech.

The life that now makes its appearance is, however, so richly and delicately formed within that it is in fact difficult for us to perceive how, over and above the content of our speaking, something is detaching itself from us in the whole body of the speech; and that is why it is so important that during his training the student should learn to apprehend what is happening here with his speaking, apprehending it with the insight of an artist. For he can do so; and it will help him more than anything else to make his speaking inwardly strong and mobile. With this end in view, let him practise his exercises as far as possible as though he were a person who cannot speak but wants to. This is a situation that can well occur in life, for it is only in connection with other human beings that we ever learn to speak.

There have been not a few instances in history of persons who have grown up in solitude, living almost the life of a wild animal. Such persons, in spite of possessing good and sound organs both for hearing and for speaking, have yet not learned to speak. If in course of time someone discovered them, he was bound to assume that they could quite well have learned to speak, and had only not done so because they were not together with other human beings.

It has generally been found, however, that human beings left in this way in solitude do make a kind of modest attempt at speaking. They will produce some such sounds as hum, ham, häm, him—that is to say, the sound h swept along into the production of gesture with some rather undefined vowel sound in between. And on investigating this groping attempt at speech, we find that as we boom out this sound-sequence, we can become conscious of how our astral body is here seizing hold of our ether body. Try uttering again and again these sounds: hum, ham, häm and so on, and you will feel as though something were liberating itself from you and living purely in vibrations. If you were to introduce this as an exercise in schools of dramatic art, and have the pupils booming out hm, it would create a most singular impression; you would feel as though a great buzzing were rising up out of you all, like an independent entity on its own. Anyone who has had this experience will readily agree that we have here an excellent first exercise for the forming of speech.

Let your students begin with practising: hm, hum, ham, häm, and it will bring movement into their speaking.

hm, hum, ham, häm.

They must of course then go on to something else; for if they continued with that exercise alone, you would be leaving them in the condition of savages. The point is, that for their start they should go back to the first elements where speech begins to free itself, begins to come forth from the human being.

Let me say here, in parenthesis, that one should not of course use this method with children. It has no pedagogical value. As soon as we begin to study things with the eye of an artist, it becomes necessary to make a clear distinction between the different spheres of life. Anthroposophy never tends to disturb or confuse the different kinds of human activity; on the contrary it assigns to each its proper sphere, and furthers its growth and progress in that sphere.

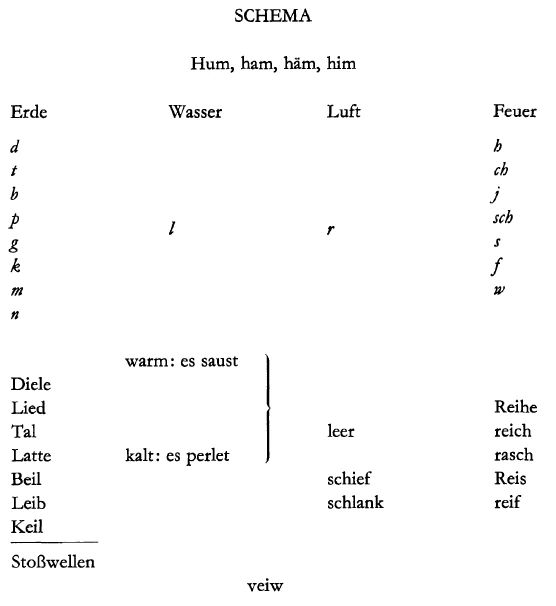

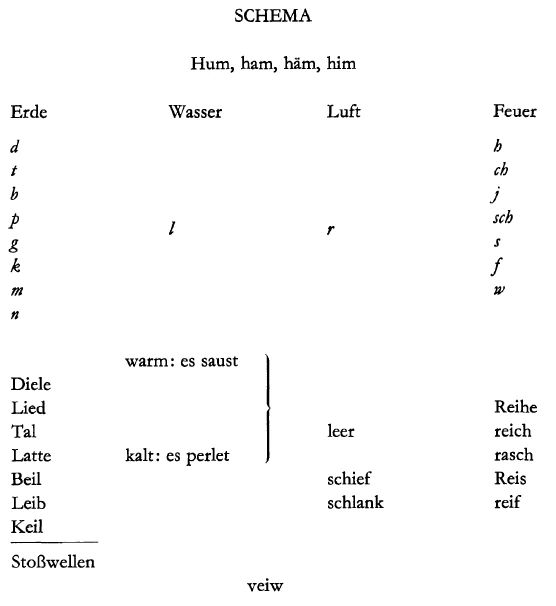

And now, how shall we continue our instruction? We have in the course of these lectures learned to distinguish among the consonants’ impact’ or ‘thrust’ sounds, and then again ‘breath’ or ‘blown’ sounds. We become either throwers of the spear (in the impact sounds) or trumpeters (in the breath sounds). In between we have the ‘wave’ sound l, and the trembling or ‘vibrating’ sound r in its various forms—the palatal r, the tongue r. These two come in between.

Now it is important to see what lies behind this grouping of the consonants For it is no arbitrary grouping, made to fit into some scheme. It is derived from the speech organism, and a fact of far-reaching significance lies behind it.

When we speak, we ‘form’ the air. This is true of all speaking of whatever kind or quality: we speak by forming the air. And we form it in ever so many different ways. Now you can get a magnificent feeling of this forming of the air, if you repeat over and over again hm, hum, ham. For you have here what I might describe as speech in full swing. Once you have experienced the great swing of speech, you will feel as you go through the impact sounds—d, t, b, p, g, k, m, n—that when you come to say hm, you would really like to achieve at long last the actual push or impact, you would like to take yourself with the hm right into it. And at the same time you can feel that you want to mould the body of the air out there in front of you to an enclosed form or figure. And you are really wanting to do this, not only with m but with all the sounds that I have named in this left-hand column (see page 378). You do not quite succeed; the endeavour shows itself only in nascent condition. Nevertheless, in the case of all these sounds there is the desire on our part to enter with them into the enclosed form that is taking shape out there in the air. As we utter these’ impact’ sounds, we feel we would like to mould the air to a complete and shut-in form. And now we can well imagine we want to go farther and see what these forms are like.

When we form the sound d, we are really wanting to form in the air a figure rather like a kind of runnel which we hold up before us like this, so that it is closed in front. That is the kind of form we want to be making as we say d.

When we say b, it is as though we were wanting to make an enclosed form rather like a little ship.

With k, we have the definite feeling of wanting to form with our speech something like a tower or pyramid

With all these sounds we are conscious of a desire to harden the air. What we would like best of all is that the air would crystallise for us. We have indeed clearly the feeling, as we utter the sounds, that actual bodily forms are there before us spirting up into the air; and we are even surprised that these forms do not begin to fly about. As we come to feel our speaking, we are astonished that when we put forth all our strength, we cannot see b and p, d and t, g and k flying about around us, that we cannot see ms flying about like spirals or ns like the curled-up tails that animals sometimes have. We are quite astonished that this does not happen. For the remarkable thing is that these impact sounds, although we form them in the air, have all the time an inclination to the earth element. With these sounds, in fact, we work right into that which is earth in the world of the elements; they are proper to the element of earth. (See table on page 378.) And from this correspondence of impact sounds with the element of earth we can learn something that will be most useful for us in our study of speech.

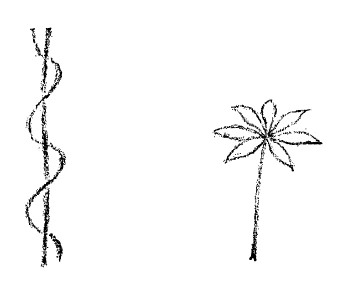

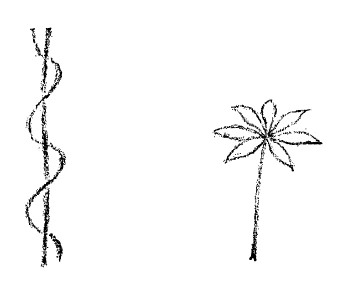

For if, as we speak k, we imagine before us a crystal form shaped somewhat like a tower, if we hold this form clearly before our mind's eye, that will do a great deal towards purifying our utterance of the sound. It will also make supple the organs we use in speaking the sound. And we shall find it a wonderful help if while speaking the sound m we imagine a climbing plant—some variety of bindweed, for example—that twines itself round the stem of another plant.

And then for n, we cannot do better than think of the woodruff, with its wreath of petals at the top of the stem.

Thus, to find the inner content of impact sounds, we have to go to the earth, we have to conjure it forth from the element of earth.

Suppose you want, for example, to get to know more intimately the inner configuration of the sound p. Call up before your mind's eye the sunflower plant, that bold-faced annual that lifts itself up to such a height. Look at its enormous overhanging golden flowers that spread out their centres so conspicuously for all to see. There you have the sound p most marvellously displayed.

To call forth from the forms and shapes in which the earth element manifests, to conjure up from them the impact sounds, will bring our speaking a stage onward. And then, what this exercise does for us will have to be brought into the lovely and smooth-running flow of speech. Let me show you how this can be achieved.

Think of the pyramid, which so well expresses a k; for as we say k, we live—in speech—in the pyramid Now let the pyramid fall down and crumble to dust. This will mean, we let the k sound pass over into the l sound, and do you see? What before was solid and firm, is now all in flow, runs away like water. k–l—it runs away like water. What is it in a Keil (a wedge) that makes it of value for you? A wedge that won't wedge itself in, a wedge that doesn't run in has no sense. The k is right too, for a wedge has a shape like a pyramid when you stand it up on end; but the main point for you about a wedge is that it slips in easily. Keil—the word is marvellously pregnant of meaning. Speak the word, and feel at the same time what the Keil does, feel the cleft it makes as it eases its way in. Feel then also how the firm solid element meets with hindrances as it goes over into flow, and how these find expression in the vowel, in the ei. In truth, a wonderful word! You can do the same with all the impact sounds. Bring them together with l, and you will find you are bringing them into a right and beautiful flow of speech.

You can also go the other way about, you can begin with something that is in flow and arrest it, establish it Practise saying the word Diele (a deal or plank). It flows in the mouth wonderfully. And now take it backwards. Set out with what is living and in flow, and carry it into the earth element, letting it become fast and firm. Diele reversed takes on a most beautiful form: Lied (a song). The song, to begin with, lives—in the soul; it is then given form, and wrought into a poem: Lied. You should learn to feel what lies behind these transitions from one sound to another.

Take now the sound t and follow it with an l. T expresses a hardening, a making firm; and then what has been made firm goes sloping away in l. In the word Tal (a dale or valley) you have a wonderful picture of this process. The land that has been pressed down hard runs out on to the plain below.

Now reverse the process. Take what is in flow and make it firm; and you have a Latte (a lath).

The sap in the living wood is in flow, and becomes hardened in the lath. Going through a word in this way, entering right into the feeling of each sound in turn, you come at last to the word's own secret.

Suppose now we go through the same process as we did with Keil, but take this time some tool we can manipulate by ourselves and turn easily in any direction. For a wedge, we usually require of course the help of a hammer; now we will take instead a tool with which we can make nearer contact—the one I have in mind is actually rather like a little boat that we can steer whither we will: Beil (an axe). The word answers well to the description and demonstrates quite clearly the difference between k and b.

Now take Beil backwards. Begin with the flow and then make it fast. Instead of bringing your axe into swing, you now bring what is alive into form, enclosing it in firm form—and you have Leib (a body).

Continued practice in uniting impact sounds with the wave sound 1 will work wonders for you. Your speaking will have clearly defined contours, and will at the same time flow well; your words will be formed and finished and yet follow one another in the sentence with ease and fluency.

From now on, therefore, let this association of impact sounds with the wave sound l be designated as the ‘Stoss-Wellen’ (Impact-Wave,—‘press-home and let-flow’). For special attention should be given to this sound-process in speech training. Students can learn from it how to form and frame their single words and at the same time also how to bring them into flow, so that the whole sentence runs like a smoothly flowing stream. All this can be learned from the practice of ‘Stoss-Wellen.’ To describe things of this kind, we have, you see, to look round for new expressions.

Taking our start in this way from impact sounds and going on to 1, we find that we have passed from earth to water. For in the impact sounds we have the element of earth and in l that which essentially signifies the fluid element, water. You can even hear in the sound an imitation of water. But now let us suppose that water becomes so tenuous that it begins to vibrate and quiver inwardly; in effect, we begin to find ourselves in the element of air. The water is evaporating, is turning gaseous, is wanting all the time to pass into the inwardly aeriform condition. This means, we are no longer satisfied to remain in the perpetual inner flow of the watery element; the inner vibration of air must now begin for us. We have this in the sound r. The air that we use for speaking, vibrates inwardly in r. R belongs to the element of air.

Imagine you have a box in front of you. You open it, hoping to find in it a present from a friend. You feel sure there is something really exciting in that box. You open it—and there is nothing there, nothing at all! And all that flow of feeling in you (l) evaporates. Before, the moisture on your tongue had been all in movement. You open the box, and air comes to meet you, nothing but quivering air. You exclaim: Leer!1Pronounce like our word ‘lair’, but letting the r vibrate. (empty). In this word leer the whole course of your experience is described—even to your starting-back which is so forcibly expressed in the double e. It would indeed be impossible to find a more adequate description of your disappointment than is given in this gesture ... and this word leer. Gesture and word taken together reproduce the experience with marvellous accuracy.

A great deal can be learned by observing words in this manner; continuing in such a study, the actor will be able to fulfil with freedom and fluency all that is required of him.

And now let us suppose that we take this vibration, this quivering, and form it, out there in the air. You will soon see what happens if you study a trumpet, not of course the metal part, but what goes on inside the trumpet when you blow. Study this carefully. Provide yourself with a highly sensitive thermometer and see what it will reveal inside the trumpet, when the vibration begins to assume forms and figures corresponding to certain tones. You will find different temperatures registered in different parts of the trumpet. This is as much as to say that the processes taking place in the trumpet express themselves in the element of fire. And the same is true of all breath sounds. When we utter feelingly the sounds: h, eh, j, sch, s, f, w, we are taken over into the element of fire or warmth. For these sounds live in the element of warmth.

You will also see from this what happens when you say hum. You set out from the warmth element; you are working, to begin with, with your own warmth. In the h you release your warmth, you let it out. Then you catch hold of what you have placed outside you and feel it as a consolidation of your being, of your whole being: hum. You take hold of your warmth and make it fast and firm: hum, ham, and so on.

Again, suppose you want to picture something that is alive, that has life in itself and is ready to go on living on its own. Continued practice with ‘breath’ or ‘blown’ sounds will bring you this experience. Words that have only such consonants are not so frequently met with, because what is alive is not posited by us as easily as are fixed objects; nevertheless you will find them here and there, where something that is outside in space is pictured as alive and unstable; and here you will again have opportunity to make interesting studies. Say, you want to express that an object is alive, but its life is uneasy, is precarious. You may describe the object as schief (aslant, on the incline).2Schief (pronounced like our word’ sheaf’) is the word used to describe the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The word itself suggests that the object could at any moment—instead of remaining in life—fall over and come to grief: schief.

Suppose, however, you want, on the other hand, to consolidate what is alive and mobile. Then you will have to see how you can make stand up straight something that is naturally, of itself, full of weaving, flowing life. Imagine before you a form. At first it is a tiny little form. It grows and grows; it rises, runs up higher and higher and becomes eventually quite tall. But now you want to express that the living, weaving form has shot up in a line. You say it is schlank (lank or slender). You begin with the sch, which tells of life, and go into the l (flowing), and then, with the k, which makes the life stand up in a straight line, you come back in the end to an impact sound.

There is still another transition that should without fail be practised by any student who wants to form his speech artistically. For he will want to be able to speak so that his speaking streams out over the audience. He will not attain this by concentrating on the individual sounds he has to utter; rather does it depend on the whole general character he is able to give to his speaking.

For an actor, this is obviously a matter of first importance. His words must penetrate to the farthest limits of the theatre, they must become a living presence throughout the space of the auditorium. This result can be achieved by the following exercise; and he who knows it will find himself in possession of an esoteric secret of the art of speech. The exercise consists in letting the vibrating air move on into breath sounds, thus: Reihe, reihen, reich, rasch, Reis, reif.

And supposing you want the very sound itself to have a hypnotising effect, you can do as the lawyer did of whom we were speaking yesterday, who advised his client to say: veiw. A fine and delicate perception lies behind the use of this sound-sequence in the piece we were studying yesterday. It is, I may say, quite wonderful how many features and details in those old plays, features that were of course introduced quite instinctively, are in perfect accord with the laws of human life.

And so, in order that our speaking shall mould the sentence plastically, we must learn to form in it especially the sounds that belong to earth and water; and for our speaking to be alive and effective we must learn to give form to the air- and fire-sounds—the air-sound r and the breath sounds. I do not mean to imply that what we say will have to be expressed with these sounds. But by practising sound sequences that contain earth sounds and the water sound, we can learn to form a sentence so that it has an inner plastic force; and we can on the other hand learn how to speak impressively, so that we may with comparative certainty assume that what we say has penetrated, has gone home, by practising the exercise I gave just now, the exercise that goes between the air sound r and the fire sounds. The actor will need to develop his speaking in both these directions: he must speak beautifully, and he must also impress his listener. And I have given you here the technique whereby he can learn both.

There is still another thing which is necessary for one who wants to make progress in the forming of speech. He has to acquire the faculty of carrying into the realm of the intimate every feeling or impression that is awakened in him from without; he must be able to bring it right home to himself in an intimate way. Let me make this clear by an example.

Take the sensation that many of you are experiencing in these days when the ‘inner configuration of the air’ in this lecture room forces itself upon your notice. Some of you, I know, feel it distinctly uncomfortable. We will take the most simple and primitive sensation that someone may have. He perceives that it is hot in here—with all the other feelings that can go with this experience. Or let us say that for his feeling the room is warm—simply warm.

Now, anyone who has interested himself at all in the forming of speech will know that a word like ‘warm’ can be spoken in a variety of ways. You are probably familiar with the delightful little story illustrative of the saying: Der Ton macht die Musik.3It's the tone that makes the music. Little Itzig writes home to his father: ‘Dear Father, send me a gulden!’ The father cannot read, so takes the letter to a notary who reads out to him in a peremptory, rude tone of voice: ‘Dear Father, send me a gulden!’ ‘Whatever next! The good-for-nothing little scamp will get no money out of me, if he writes like that! Is that really what he says?' But now the poor father cannot after all find it in his heart to leave the matter at that, so he goes to the parson. The parson takes the letter and reads out to him in a gentle, quiet tone : ‘Dear Father, send me a gulden!’ ‘Is that really what he says?’ ‘Certainly!’ replies the parson. ‘The dear little fellow, I'll send him one right away!’ Yes, everything depends, you see, on the tone of voice! Similarly, the word `warm' can be spoken in many different ways. But, my dear friends, if that is so, we must be able to bring into the sounds of the word all the different fine shades of feeling that we want to express. And that has to be learned; we have to learn how to do it.

Let us return to our supposition that someone feels the room warm. (I choose this for my example, since I have a suspicion that quite a number of you may be experiencing this feeling at the present moment.) And now let him follow the experience back into the subjective. Let us imagine he shuts his eyes, forgets there are other people around him and says to himself: Es saust (I feel a buzzing or whizzing sensation in my head!). He calls the ‘being warm’ a sensation of buzzing because he can feel it like that when he withdraws into himself and experiences it subjectively. Try to distinguish different kinds of buzzing that you can experience. When you are very cold, you feel inside you quite another kind. One could imagine, it might almost become a habit to have, when the room is warm, this inner sensation of buzzing.

warm: a buzzing sensation.

Practise this, entering into the inner feeling of it; and it will help you to make your intonation of the word ‘warm’ accord with the precise shade of experience that you want it to express. Exercises of this kind should be included in your training.

Take another: I am cold. Es perlet (I feel a tingling, a stinging sensation—and this time, especially in my legs and arms).

cold: a tingling or stinging sensation.

The more of such examples that you can find for yourselves, the better. See where you can take some word that expresses a perception or sensation, and lead it over into an experience that is more intimate, that touches you more nearly. To carry over in this way a perception that is at first more remote and separate into the realm of the intimate will give to your speaking the right inner ‘feeling’ tone.

So we have now four properties of speech:

The feeling tone of speech,

The beautiful, smooth flow of speech,

The revelation of oneself that is given out in speech,

The penetrating and convincing power of speech.

These are, every one of them, a matter of technique. The actor has simply to learn the technique for achieving them.

In past ages, such things were known instinctively, and men were also aware of their fine spiritual significance. In the school of Pythagoras, for example, the pupils had to recite strongly marked rhythms, the aim being to intervene by this means in human evolution, taking hold of what was instinctive and developing it further by education.

Take a line of verse that runs in trochees or dactyls, such as:

Singe, unsterbliche Seele, der sündigen Menschen Erlösung!4Sing, O immortal soul, the redemption of sinful mankind!

A rhythm of this nature, chanted in a kind of singing recitative, Pythagoras would use in his school to tame the passions of men. He knew its power. And he knew also that verse in the iambic rhythm has the.effect of stirring up the emotions. Such things were well known to the men of earlier times, just as they knew too that the art of music takes us back to the Gods of the past, the plastic and pictorial arts lead us an to the Gods of the future, while the art of drama, standing between the two, conjures up the Spirits of the time in which we live.

We too must learn to perceive truths of this nature. A knowledge of them must return again among mankind; only then will art be able to take its right place in life.

It is really also quite remarkable how strongly the instinctive can still make itself feit in this domain. Look at the popular poetry composed by the Austrian poet Misson, the Piarist monk who wrote in dialect. If you study Misson's biography and read of all the other things that he did, you will find that he obviously wanted this poetry to have a soothing, calming effect. He accordingly chose for it, not the iambic metre but, notwithstanding that he was writing in dialect, the hexameter.

Naaz, iazn loos, töös, was a ta sa, töös sàckt ta tai Vada.

Gottsnam, wails scho soo iis! und probiast tai Glück ö da Waiden.

Muis a da sàgn, töös, was a da sa, töös las der aa gsackt sai.

Ih unt tai Muida san alt und tahoam, wöast as ee, schaut nix aussa.

Was ma sih schint und rackert und plàckt und àbi ta scheert töös

Tuit ma für d'Kiner, was tuit ma nöd ails, bald s'nöd aus der Art schlàgn’!—

Es mar aamàl a presshafts Leut und san schwari Zaiden,

Graifan s' am aa, ma fint töös pai artlinga rachtschàffan Kinern ...

You can feel, as you listen to the lines, their soothing, quieting influence.

If you want to lead straight over to the spiritual, if you want to take your hearers away from the physical and lead them up to where they can move in the realm of the spirit, then you will have to use the iambic metre, but still forming the speaking gently, quietly.

And this is one of the reasons that prompted Goethe, for example, to write his dramas in iambics, one of the reasons also why our Mystery Plays have been written largely in iambic verse. A sensitive perception for such things will have to live within us, if we want to have again true schools of dramatic art. In such schools it must be known that speech is alive, that gesture is alive, that everything that happens on the stage is alive and active and sends its influence out far and wide.

or, using English letter:

17. Das Durchfühlen des Lautlichen

In Zeiten, in denen das, was durch die Sprache aus den Menschen heraus sich offenbarte, noch instinktiv intensiver empfunden worden ist, wurde man jenes realen Vorganges gewahr, der wirklich im Sprachgestalten da ist, jenes realen Vorganges, der darinnen besteht, daß mit einer gewissen Selbständigkeit der astralische Leib des Menschen den ätherischen ergreift. In der Gegenwart reden eben die Menschen, wie sie ja alles einfach so tun, daß sie nicht gewahr werden die Komplikationen des inneren Vorganges, der sich bei einem menschlichen Tun abspielt. Es ist auch richtig, daß die Dinge nicht allzu stark während des Tuns beobachtet werden dürfen, sonst vertreiben sie die Unbefangenheit. Aber derjenige, welcher mit Sprachgestaltung und mit dem Mimisch-Gebärdenhaften künstlerisch zu tun hat, hat nötig, wenigstens während der Zeit seiner Schulung so etwas vor die Seele bekommen zu haben, wie dieses Selbständigwerden eines Arbeitens, eines Zusammenarbeitens von astralischem Leib und Ätherleib.

Man muß das Gefühl durchgemacht haben, was es heißt — Gefühl, sage ich, nicht Anschauung -, es hat sich gewissermaßen ein zweiter Mensch, der in dieser Arbeit zwischen astralischem Leib und Ätherleib besteht, losgelöst und lebt in der Sprache.

Nun ist dieses Leben, so wie es jetzt auftritt, schon ein so innerlich konfiguriertes und innerlich reich gestaltetes, daß es dem Menschen in der Tat schwer wird, über den Inhalt der Sprache hinüber auch noch wahrzunehmen, wie sich da im ganzen Sprachkörper etwas aus ihm heraushebt.

Daher ist es gut für die Schulung, dasjenige, was da eigentlich vorliegt, mit wirklicher Kunst zu ergreifen. Und man kann es ergreifen. Man kann es auf folgende Weise ergreifen und dadurch wiederum Ungeheutes beitragen zum innerlich Kraftvoll- und Beweglichmachen der Sprache. Man kann es dadurch machen, daß man möglichst so übt wie jemand, der eigentlich nicht sprechen kann und doch sprechen will. Dasjenige, was ich Ihnen da sage, ist insofern doch eine Realität, als der Mensch sprechen nur lernen kann im Zusammenhange mit anderen Menschen.

Nun ist es wiederholt vorgekommen, daß Menschen einsam in der Wildnis, fast tierisch aufgewachsen sind. Die haben dann trotz gesunder Gehör- und gesunder Sprachorgane nicht sprechen gelernt. Und hat man sie später aufgefunden, so mußte man sich sagen, die hätten ganz gut sprechen lernen können, haben es aber nicht gelernt, weil sie nicht mit anderen Menschen zusammen waren. Aber solche Menschen werden zumeist, ich möchte sagen, einen leisen Ansatz zum Sprechen dennoch machen. Und der wird darinnen bestehen, daß sie so etwas wie ein hum, ham, häm, him hervorbringen, eine Strömung von der s-Erzeugung zu der »-Erzeugung mit etwas undeutlichen Vokalen dazwischen. Frägt man nun nach, so ist es in der Tat so, daß der Mensch, indem er diesen Lautzusammenhang herausbrummt, gewahr werden kann, wie da in ihm der astralische Leib den Ätherleib abfängt. Wenn man versucht, immer wieder hum, ham, häm und so weiter hervorzubtingen, dann fühlt man, wie wenn sich etwas loslöste, in reinen Vibrationen lebte. Und führte man dies in Schauspielschulen ein, daß in dieser Weise gebrummt würde das hm, so würde man etwas Merkwürdiges wie ein innerliches selbständiges Sausen fühlen, das aus einem herauswächst. Wer so empfinden lernt, wird schon zugeben, daß das eine rechte Grundübung sein kann. Nur muß sie dann weitergeführt werden. Man fängt also an damit, dem Zögling hm, hum, ham, häm zur Beweglichkeit seiner inneren Sprachfähigkeit beizubringen. Dann geht man aber zu etwas anderem über, denn damit würde man natürlich ein Wilder bleiben, und es handelt sich nur darum, daß man aus dem ersten Elemente des Sich-Loslösenden der Sprache wirklich heraus arbeitet.

Ich bemerke nur, wie in Parenthese, daß man das bei Kindern natürlich nicht tun darf. Einen pädagogischen Wert hat das nicht, was ich jetzt sage. Denn es ist notwendig, daß man gerade dann, wenn die Dinge ins wirklich Künstlerische übergehen, die einzelnen Gebiete sondert, daß man nicht alles überall anwendet. Das eigentlich Fachliche wird durch das Anthroposophische nicht zerstört, sondern im Gegenteil an seinen Ort gestellt und gefördert.

Nun besteht das Weiterschreiten dann in dem Folgenden. Wir haben ja zunächst diejenigen Laute kennengelernt, die wir als Stoßlaute unter den Konsonanten, dann diejenigen Laute, die wir als Blaselaute bezeichnet haben. Wir werden entweder zum Speerwerfer in den Stoßlauten, oder aber wir werden zum Trompeter in den Blaselauten. Dazwischen liegt der Wellenlaut l und der Zitterlaut in seinen verschiedenen Gestaltungen als Gaumen-r, als Zungen-r, Lippen-r, der r-Laut als Zitterlaut. Die liegen dazwischen.

Nun muß man durchschauen, was da eigentlich dahinter steckt bei dieser Gliederung der Laute, die nicht von uns willkürlich aufgestellt ist. Es ist ja keine schematische Einteilung, sondern es ist aus dem Organismus der Sprache herausgenommen. Und da steckt etwas sehr Bedeutsames dahinter. Wir sprechen allerdings im Ganzen, indem wir die Luft gestalten. Gewiß, das ist der gemeinsame Charakter alles Sprechens, daß wir die Luft gestalten, aber wir gestalten die Luft in der allerverschiedensten Weise.

Nun, dieses Luftgestalten gerade, das verspüren Sie in einer grandiosen Weise, wenn Sie immer wieder und wiederum hm, hum, ham formen. Sie haben darinnen, ich möchte sagen, den allgemeinsten Schwung der Sprache. Und haben Sie das erlebt, diesen allgemeinsten Schwung der Sprache, dann werden Sie bei denjenigen Lauten, die ich als Stoßlaute bezeichnet habe, also bei d t b p g k m n, das Gefühl bekommen, daß Sie, wenn Sie hm machen, das Stoßen eigentlich zuletzt erreichen wollen. Da wollen Sie mit dem hm ins Stoßen herein. Sie können fühlen, da wollen Sie den Luftkörper zu einer geschlossenen Figur machen. Bei allem, was hier auf dieser Seite steht — siehe Schema Seite 354 -, ist es so, daß wir ähnlich dem m, welches aber dies noch nicht ganz vollendet zeigt, sondern im Status nascens, hineinwollen in die geschlossene Form der Luft, des Luftkörpers, zu einer Figur. Bei allen Stoßlauten fühlen wir, wie wir eigentlich eine geschlossene Figur bilden wollen. Und wir können uns vorstellen, wir wollen weiter.

Indem wir d bilden, wollen wir eigentlich vor uns eine solche geschlossene Luftfigur bilden: eine Art Röhre, die vorn geschlossen ist, die wir vor uns aufrichten, wollen wir bei dem d bilden.

Wenn wir b sprechen, ist es eigentlich so, als ob wir so eine Art kleines Schiff als geschlossene Figur bilden wollen.

Bei k haben wir ja das deutliche Gefühl, daß wir so etwas wie einen Turm bilden wollen mit der Sprache, eine Pyramide.

So haben wir sehr deutlich das Gefühl, da wollen wir die Luft verhärten. Und am liebsten wäre es uns, wenn sich die Luft kristallisieren würde. Wir haben so eigentlich das Gefühl, wenn wir die Laute aussprechen, daß da in die Luft hineinprojiziert werden Körperformen; und wir sind erstaunt darüber, daß die da nicht herumfliegen, weil wir schon, wenn wir die Sprache fühlen, uns so stark anstrengen, daß eigentlich das b und p, d und t, g und k herumfliegen, und die m wie Spiralen und die n wie manche Tierschwänze herumfliegen. Wir sind eigentlich erstaunt, daß das nicht der Fall ist. Denn diese Stoßlaute sind dasjenige, was, trotzdem wir in der Luft formen, fortwährend hinstrebt zum Erdenelemente. In das Elementar-Erdige arbeiten wir hinein mit diesen Stoßlauten; so daß diese Stoßlaute entsprechen dem Element Erde. (Siehe Schema.)

Das hat aber wieder etwas außerordentlich Instruktives und führt uns zu dem, was für das richtige Lernen außerordentlich bedeutsam sein kann, denn sehen Sie, es ist tatsächlich für das Reinigen der Sprache, für das Gelenkigwerden der Organe in bezug auf die Sprache von einem großen Vorteil, wenn wir uns eine Kristallgestalt vorstellen, indem wir k sprechen, so eine turmförmige Kristallgestalt. Dieses starke Vorstellen, das unterstützt uns im k-Sprechen.

Es ist außerordentlich vorteilhaft, wenn wir uns, während wir m sprechen, eine Schlingpflanze vorstellen, die sich hinaufwindet an einem Stock, so eine Winde, während wir m sprechen.

Und es ist von einem großen Vorteil, wenn wir » sprechen, uns den Waldmeister vorzustellen, der da oben solch einen Kranz von Blättern hat; wenn wir also sozusagen dasjenige aus der Erde herauszaubern, was in den Stoßlauten liegt.

So bekommen Sie zum Beispiel immer mehr und mehr die innere Konfiguration des p heraus, wenn Sie sich die Konfiguration der Sonnenblume vorstellen, diese freche, hochwachsende Blume mit überhängenden, riesigen gelben Blüten, die so auffallend uns die Mitte ihrer Blüte entgegenstreckt. Dadrinnen liegt das p in einer ganz außerordentlich schönen Weise.

Herauszuholen aus den irdischen Gestaltungen die Stoßlaute, das ist dasjenige, was uns wirklich im Sprechen weiterbringt. Aber all das, was wir in dieser Weise üben, kann in den schönen Fluß der Sprache übergehen, wenn wir es eben. verfließen lassen, wenn wir so eine Pyramide, die eigentlich ein k darstellt und in der wir innerlich in der Sprache leben, während wir k sagen, dazu bringen, daß sie verfließen muß, daß sie sich auflösen muß. Dann lassen wir den k-Laut übergehen in den l-Laut, und Sie werden sehen, das fließt weg wie Wasser, was da erst ganz fest ist. K, l = das fließt weg wie Wasser. Und was interessiert Sie denn, wenn Sie das Wort Keil sagen? Ein Keil, der nichts keilt, der also nicht verfließt in seiner Bewegung, hat ja keinen Sinn, und ein Keil hat ein k ganz richtig, weil er eine Pyramide ist, wenn man ihn aufstellt. Aber dasjenige, was uns am Keil interessiert, ist, daß er verfließt. Also das ist ein Wort von einer inneren Prägnanz, die großartig ist! Und sagen Sie Keil und fühlen dasjenige, was der Keil tut, fühlen Sie etwas zerspalten dabei, und dieses Übergehen in den Fluß unter Hemmnissen, die Hemmung wiederum durch das ei ausgedrückt, durch das Vokalische, dann haben Sie ein Wunderbares.

Und so können Sie alle Stoßlaute in den richtigen schönen Fluß der Sprache hineinbringen, wenn Sie sie mit einem l zusammenbringen. Sie können aber auch wiederum das Flüssige verfestigen, wenn Sie die umgekehrte Prozedur machen. Üben Sie Diele. Diele: es fließt wunderbar im Munde. Und wollen Sie das Umgekehrte machen, dasjenige, was zunächst lebt, dann wiederum wunderschön in seine Gestaltung hinein als Flüssiges in das Sich-Verfestigende-Erdige hineinlebt: Lied. Es lebt das Lied zunächst in der Seele, wird dann gestaltet in dem Dichten: Lied.

Lernen Sie fühlen, was in so etwas liegt. Nehmen Sie den Stoßlaut t, lassen Sie irgendwie ein l folgen. Man hat ein hartes Sich-Verfestigen in dem t, aber es läuft doch dahin, dieses harte Sich-Verfestigen. In dem Worte Tal haben Sie es wunderbar ausgedrückt, das dahinlaufende Hinuntergestoßene.

Kehren Sie es um, nehmen Sie zunächst das Flüssige und machen Sie es dann fest, da haben Sie förmlich, wenn das das Tal ist, weil Sie da durchgehen, wenn Sie dasjenige sich fest denken, was da drinnen ist: Latte. Da ist es zuerst flüssig, und dann wird es fest in der Latte.

Sehen Sie, auf diese Weise kommen Sie zum Durchfühlen des Lautlichen bis in das Wortgeheimnis herein. Versuchen Sie nur einmal, dieselbe Prozedur, die wir beim Keil gehabt haben, mehr so zu machen, daß man wie etwas vor sich her dirigiert, was man mehr handhaben kann als einen Keil, den man ja nur mit einem Hammer handhaben kann, etwas, was also schon dem Menschen näherliegt, was schon eher so ist, wie ein kleines Boot, das man vor sich her dirigiert, so haben Sie Beil. Da spüren Sie den Unterschied zwischen k und b - Keil und Beil - an dem Ganzen, was das ist, deutlich darinnen.

Aber gehen Sie jetzt zurück. Haben Sie zuerst das Flüssige und dann verfestigen Sie es, so daß es Ihnen nicht darauf ankommt, das Beil in Fluß zu bringen, sondern dasjenige, was leibt und lebt, in feste Gestalt, Umhüllung zu bringen, dann haben Sie den Leib.

Und so können Sie in dem Üben der Verbindung der Stoßlaute mit dem Wellenlaut l wunderbar erreichen, daß die Sprache wie geschlossen und doch flüssig wird, daß Ihre Worte konfiguriert werden und doch der Satz hinläuft so, daß eines in das andere übergeht.

Daher sollte man in der Zukunft dasjenige, was da vorliegt, was man immer zuwege bringt, wenn man Stoßlaute mit dem l, mit dem Wellenlaut, zusammenfügt, im Zusammenhange zur Sprachübung verwendet, als das Stoß-Wellen in der Sprachgestaltung bezeichnen.

Es sollte eben ein Kapitel sein, das den Umfang hat, zu lehren, wie man die Worte im Satze auf der einen Seite begrenzt, auf der anderen Seite so in Fluß bringt, daß sie den Satz als eine Strömung darstellen. Und das sollte man lernen im Stoß-Wellen. Für diese Sache müssen neue Ausdrücke gewählt werden.

Nun aber kommen wir da mit den Stoßlauten und mit dem l ins Flüssige hinein, so daß wir sagen können: Wir haben in den Stoßlauten Erde, im l dasjenige, das im wesentlichen das Wasser bedeutet, das Element Wasser. Das wird in der Sprache nachgestaltet, daß Wasser in dem l ist.

Nehmen Sie aber an, das Wasser wird jetzt so dünn, daß es nun innerlich beweglich wird, daß wir in die eigentliche Luft hereinkommen, daß das Wasser immer mehr verdunstet, Gas wird, es will in das innerliche Luftförmige hereinkommen, dann leben wir nicht mehr zufrieden mit dem innerlichen Dahinfiießen und Wellen, sondern dann muß die Luft innerlich erzittern. Und die Luft, die wir zur Verfügung haben im Sprechen, erzittert innerlich im r. Das r entspricht dem Elemente Luft. Fühlen Sie doch einmal, wie, wenn Sie, ich will so sagen, eine Schachtel haben. Sie machen Sie auf und denken, da ist ein Geschenk darinnen. Sie vermuten, daß das, worauf Sie sich freuen, was innerliche Bewegung in Ihrer Seele hervorruft, darinnen ist. Es ist aber nicht darinnen; es ist nichts darinnen; es verflüchtigt sich alles das, was erst flüssig war = l. Sie bewegen die Flüssigkeit auf Ihrer Zunge, machen auf und die bloß erzitternde Luft tritt Ihnen entgegen, und Sie brechen aus in den Laut: leer! Da haben Sie es ganz anschaulich. Sie haben durchempfunden das Wort bis auf das Zwurückbeben im doppelten ee: leer, das besonders stark ist.

Man kann sich nicht denken, daß etwas adäquater sein könnte als auf der einen Seite diese Gebärde und dieses Wort leer. Beides ist ganz genau anzuschauen. Aber an solchen Dingen kann man wirklich viel lernen. Besonders für die freie Handhabung desjenigen, was man als Schauspieler braucht, kann man dabei außerordentlich viel lernen.

Und jetzt denken Sie sich, Sie nehmen dieses Zittern da auf und konfigurieren es in der Luft. Sie formen das Zittern. Sie brauchten bloß die Trompete ordentlich zu studieren, das heißt nicht das Metall, sondern was da vorgeht in der Trompete, während Sie blasen. Versuchen Sie es nur einmal, mit ganz feinen Temperaturmessern nachzuschauen, was da im Inneren der Trompete sich zeigt, wenn das bloße Zittern übergeht in die geformte Tonfigur. Da haben Sie überall Wärmedifferenzen in der Trompete darinnen. Das drückt sich aus in dem Element des Feuers. Daher gehen auch alle Blaselaute über in das Element des Feuers oder der Wärme, das wir haben, wenn wir fühlend aussprechen: h ch j sch s f w. Das lebt im Elemente der Wärme. Daher ist es auch so, wenn Sie anfangen mit dem h, arbeiten Sie Ihre Wärme heraus, Sie entledigen sich Ihrer Wärme im h, dann fangen Sie es auf, was Sie herausgesetzt haben, indem Sie es fühlen wie eine Verfestigung Ihres zweiten Menschen: hm. Ihre Wärme, die Sie bis zum Festen bringen: hum, ham und so weiter.

Nun kann man wiederum fühlen, wie man dasjenige, was man vor sich hinstellen will, was leben will in Weiterleben, was man hinstellen will wie etwas selbständig Lebendiges, dann bekommt, wenn man unmittelbar in Blaselauten übt. Blaselaute, Sie werden sie üben können in Worten, die nicht gerade häufig sind, weil das Lebendige vom Menschen nicht so hingestellt wird wie das Feste, aber immerhin, Sie werden Blaselaute überall da besonders finden, wo irgendwie draußen im Raum etwas so dargestellt wird, daß es lebt, daß es schwankt. Und da kann man interessante Studien wieder machen. Will man nur ausdrükken, daß etwas eigentlich unangenehm lebt = schief; es liegt schon im Worte schief, daß es immer eher umfallen kann als leben: schief.

Empfindet man aber so, daß man das Bewegliche, Lebende hinein haben will in das Feststehende, dann wird eine Notwendigkeit entstehen, das äußerlich selbständig Webende und Lebende, lebend Flüssige aufstellen zu wollen. Nun denken Sie sich einmal, ich habe eine Gestalt, sie ist zuerst klein, wächst, wächst, fließt da hinauf. Aber will ich ausdrücken, daß das eigentlich in der Linie schreitendes Leben, Weben ist, dann sage ich: schlank. Gehe ich über von dem sch, was das Leben darstellt, in das Flüssige und komme dann zu dem, was aufstellt dieses Leben in der Linie = schlank, so komme ich zu dem Stoßlaut k zurück.

Insbesondere aber kann man dasjenige üben, was man auch braucht gerade in der künstlerischen Sprachgestaltung. Da braucht man die Fähigkeit, so zu sprechen, daß das Sprechen dahinfließt über das Auditorium. Das braucht dann nicht auf die Laute und Buchstaben konzentriert zu sein, sondern das liegt in dem allgemeinen Charakter, den man sich überhaupt für das Sprechen aneignet.

Für den Schauspieler wird es ganz besonders notwendig sein, daß er das zuwege bringt, daß seine Worte durch den Zuschauerraum gehen, daß sie überall leben. Das kriegt er zustande — und dies zu wissen, darin besteht nun eine besondere Esoterik der Sprachgestaltung -, wenn er das Erzittern der Luft in Bewegung bringt durch den Übergang in Blaselaute, wenn er also übt: Reihe, reihen, reich, rasch, Reis - es liebt dieser Übergang das ei nicht - reif.

Und will man, daß der L.aut selber wie hypnotisierend auf jemanden wirkt, so kann man das machen, was der Advokat, von dem ich gestern gesprochen habe, mit seinem Klienten gemacht hat; man kann ihm raten, zu sagen: veiw. Es ist mit außerordentlich feiner Empfindung in dieses Stück, von dem ich gestern gesprochen habe, hineingekommen. Instinktiv leben in diesen Sachen manchmal ganz wunderbare gesetzmäßige Dinge.

Und so sehen Sie, daß man das Sprechen, welches den Satz gestaltet, dadurch zuwege bringt, daß man lernt, es an den erde-wäßrigen Lauten zu gestalten, und dasjenige, was anredet, mit den luftförmigfeurigen Lauten, mit dem Zitterlaut r und mit den Blaselauten gestaltet. Nicht als ob man das mit diesen Lauten ausdrücken müßte, aber lernen kann man, einen Satz ordentlich gestalten, so daß er eine innerliche plastische Kraft hat, wenn man Zusammenhänge übt, in denen die Erdenlaute und der Wasserlaut sind, lernen kann man, eindringlich zu sprechen, so daß man mit einer gewissen Sicherheit annehmen kann, es wird aufgenommen.

Lernt man, wenn man übt, zwischen dem Luftlaut r und den Feuerlauten, welche die Blaselaute sind, diese Übungen zu machen - und beides muß der Schauspieler lernen, er muß schön und eindringlich sprechen -, so ist dies der Weg, um wirklich technisch schön und eindringlich sprechen zu lernen.

Es gibt noch ein anderes, was notwendig ist für den, der in der Sprachgestaltung vorwärtskommen will. Das ist, er muß die Fähigkeit bekommen, jede Empfindung aus dem Fremderen in das Intimere umzusetzen.

Ich will Ihnen das in der folgenden Weise klarmachen. Nehmen Sie die Empfindungen, die manche von Ihnen haben an denjenigen Tagen, wo hier die innere Konfiguration der Luft in diesem Raume besonders zum Ausdruck kommt. Es gibt Menschen, die das so empfinden, daß es ihnen unbehaglich ist. Nun, wollen wir die primitivste Empfindung nehmen, die jemand haben kann. Er hat die Empfindung, es ist heiß im Saal mit all den Nebenempfindungen, die man da haben kann, heiß, warm, sagen wir bloß warm. Also: Es ist warm im Saal.

Nun wird jeder, der sich ein wenig mit Sprachgestaltung befaßt hat, wissen, daß man das Wort warm in der verschiedensten Weise sagen kann im Leben. Sie kennen ja die hübsche Anekdote, die illustriert: Der Ton macht die Musik. - Der kleine Itzig schreibt von der Ferne her an seinen Vater, der nicht lesen kann: Vaterleben, schick mir einen Gulden. — Der Vater kann nicht lesen und geht zum Notar, läßt sich das vorlesen: Vaterleben, schick mir einen Gulden! - [Grob.] Was? Der nichtsnutzige Schlingel kriegt von mir nichts, wenn er so schreibt! Hat er wirklich so geschrieben?

Nun, aber das Vaterherz will doch die Sache nicht gleich so hinnehmen, geht noch zum Pfarrer. Der liest ihm vor: Vaterleben, schick mir einen Gulden. - [Sanft.] Hat er wirklich so geschrieben? — Ja, jal — Ach, ich will ihm heute noch einen Gulden schicken, sagt der Vater. — Ja, Sie sehen, der Ton macht eben die Musik.

Nun, man kann das Wort warm in der verschiedensten Weise aussprechen. Aber, meine lieben Freunde, wenn man das Wort warm in der verschiedensten Weise ausspricht, dann muß man es auch können. Man muß es lernen, in den Laut das hineinzutragen, was man eigentlich gefühlsmäßig will; man muß das in den Laut hineintragen können. Das muß man auch lernen. Denken Sie sich daher einmal, jemand empfindet dieses warm hier in diesem Saal. Ich will etwas aufgreifen, was vielleicht eine Anzahl von Ihnen jetzt eben empfinden kann: warm.

Nun kann man, wenn man das empfindet, auf das Subjektive zurückgehen. Denken Sie sich, es macht dann jemand, der hier warm empfindet, die Augen zu, vergißt, daß die Leute da sind im Saal und sagt: Es saust. - Er nennt das Warmsein Sausen, weil er es auch so erleben kann, wenn er auf das Subjektive zurückgeht. Versuchen Sie nur einmal wahrzunehmen, wie es verschieden saust. Wenn es kalt ist, wenn Sie frieren, saust es ganz anders, als wenn es warm wird. Aber nehmen Sie einmal so, daß es fast Gewohnheit wird, das Warmsein, daß Sie empfinden: Es saust...

Also warm = es saust.

Wenn Sie dies jetzt rein empfindungsmäßig schulen, dann lernen Sie dadurch diese Intonierung des warm anmessen dem, was Sie eigentlich ausdrücken wollen. Und so ist es gut, auch solche Übungen noch zu machen.

Kal = es perlet.

Es perlet, und zwar in den Gliedern. — Und in dieser Weise, je mehr man sich solche Sachen selber bildet, desto besser ist es, in dieser Weise einen Ausdruck für eine Empfindung in etwas überzuführen, was einem intimer, näher liegt. Also das Fernere überzuführen in die Bezeichnung des Intimeren, das gibt der Sprache den inneren Gefühlston.

So haben Sie:

innerer Gefühlston der Sprache, der schöne Fluß der Sprache, das sich nach außen Offenbaren, das eindringliche Überzeugende der Sprache.

Diese Dinge sind eben nur auf technischem Wege wirklich zu lernen. Und der Schauspieler muß sie lernen.

Von solchen Dingen hat man einstmals instinktiv viel gewußt, und man hat die spirituellen, die geistigen Bedeutungen der Dinge gut gewußt. Und so war es zum Beispiel in der pythagoreischen Schule üblich, mit besonders dezidierten Rhythmen die instinktive Entwickelung des Menschen zu ergreifen und sie erzieherisch zu fördern.

Nehmen Sie an, es fließt ein Versmaß trochäisch oder daktylisch ab: Sing, unsterbliche Seele, der sündigen Menschen Erlösung. — Ja, sehen Sie, solch einen Rhythmus, mehr ins Rezitativ-Gesangliche überführt, hat Pyzhagoras in seiner Schule benützt, um die Leidenschaften leidenschaftlicher Menschen zu zügeln. Während er ganz gut gewußt hat, daß ein jambischer Fluß eher die Emotionen in Fluß bringt. Diese Dinge hat man eben durchaus gewußt, wie man gewußt hat, daß das Musikalische zurückführt zu den Göttern der Vorzeit, das Bildnerische zu den Göttern der Zukunft führt, und die Schauspielkunst steht mitten darinnen als dasjenige, was die Geister der Gegenwart bannte.

Aber solche Gesinnungen muß man entwickeln. Sie müssen wiederum unter die Menschheit kommen, damit die Kunst eingetaucht sein kann in ihr richtiges Element. Und es ist doch eigentlich merkwürdig, wie das Instinktive da wirkt.

Sehen Sie, als der österreichische Dialektdichter, der Piaristenmönch Misson, eine Volksdichtung machte, da sieht man aus alledem, was er sonst getan hat, wenn man seine Biographie kennt, daß er eigentlich mit einer solchen Dichtung auf das Besänftigende wirken wollte; daher hat er keinen jambischen Vers gewählt, sondern, trotzdem er Dialekt schreibt, den Hexameter:

Naaz, iazn loos, töös, wàs a ta så, töös sàckt ta tai Våda.

Gottsnàm, wails scho soo iis! und probiast tai Glück ö da Waiden.

Muis a da sàgn töös, was a da sä, töös lås der aa gsàckt sai.

Ih unt tai Muida san àlt und tahoam, wóast as ee, schaut nix aussa.

Wås ma sih schint und rackert und plàckt und àbi ta scheert töös

Tuit ma für d’Kiner, was tuit ma nöd àlls, bald s’ nöd aus der Art schlàg’n!

Iis ma aamàl a preßhafts Leut und san schwari Zaiden,

Graifan s’ am aa, ma fint töös pai artlinga rechtschàffan Kinern...

und so weiter. Man fühlt darinnen das Besänftigende.

Will man direkt zum Spirituellen hinüberleiten, hinaufleiten zur spirituellen Bewegung, will man vom Physischen ins Geistige hineinführen, dann muß man in einer sanftgestalteten Sprache gerade aber jambisch gestalten.

Und da haben Sie auch eines der Motive, warum Goethe eben seine Jamben-Dramen geschrieben hat, warum die Mysterien zum großen Teil in Jamben geschrieben sind und so weiter. Das sind Dinge, welche durchaus lebendig werden müssen, wenn wir wiederum Schauspielschulen bekommen wollen. Und da muß man wissen, wie die Sprache lebt, wie die Gebärde lebt, wie alles dasjenige wirkt im weiten Umkreis, was auf der Bühne vorgeht. Daran wollen wir dann morgen anknüpfen. Wie gesagt, ich habe noch morgen und Dienstag zur Abrundung zwei Vorträge über Sprachgestaltung und dramatische Darstellung.

17. Feeling through the sound

In times when what was revealed through language was still felt more intensely and instinctively, people were aware of the real process that is truly present in the formation of language, the real process that consists in the astral body of the human being grasping the etheric body with a certain independence. Nowadays, people speak, as they do everything else, without becoming aware of the complications of the inner process that takes place in human activity. It is also true that things should not be observed too closely during the act, otherwise they dispel impartiality. But those who are artistically involved in speech formation and mimicry need, at least during their training, to have experienced something like this independence of working, this cooperation between the astral body and the etheric body.

One must have experienced the feeling of what it means — feeling, I say, not perception — that a second human being, consisting of the astral body and etheric body, has detached itself and lives in language.

Now this life, as it appears at present, is already so inwardly configured and richly structured that it is indeed difficult for human beings to perceive, beyond the content of language, how something in the whole body of language stands out from it.

Therefore, it is good for training to grasp what is actually present with real artistry. And one can grasp it. One can grasp it in the following way and thereby contribute enormously to making language internally powerful and mobile. One can do this by practicing as much as possible like someone who cannot actually speak but still wants to speak. What I am telling you here is a reality insofar as human beings can only learn to speak in connection with other human beings.

Now, it has happened repeatedly that people have grown up alone in the wilderness, almost like animals. Despite having healthy hearing and healthy speech organs, they did not learn to speak. And when they were found later, one had to say to oneself that they could have learned to speak quite well, but did not learn to do so because they were not with other people. But such people will usually, I would say, make a quiet attempt to speak nonetheless. And this will consist of them producing something like a hum, ham, häm, him, a flow from the production of s to the " production with somewhat indistinct vowels in between. If one inquires further, it is indeed the case that by humming out this sound connection, the person can become aware of how the astral body intercepts the etheric body within them. If one tries to produce hum, ham, häm, and so on again and again, one feels as if something has detached itself and lives in pure vibrations. And if this were introduced in drama schools, that the hm should be hummed in this way, one would feel something strange, like an inner, independent whirring that grows out of oneself. Anyone who learns to feel this way will admit that this can be a proper basic exercise. But then it must be continued. So one begins by teaching the pupil hm, hum, ham, häm to develop the mobility of his inner speech ability. But then one moves on to something else, because otherwise one would naturally remain wild, and it is only a matter of really working out of the first element of detaching oneself from language.

I would just like to note, as an aside, that one must not do this with children, of course. What I am about to say has no educational value. For it is necessary, precisely when things transition into the truly artistic, to separate the individual areas, so that one does not apply everything everywhere. The actual subject matter is not destroyed by anthroposophy, but on the contrary, it is put in its place and promoted.

Now, the next step consists of the following. We first learned about the sounds that we call plosives among the consonants, then the sounds that we have called fricatives. We either become spear throwers in the plosives, or we become trumpeters in the fricatives. In between lies the wave sound l and the trill sound in its various forms as palatal r, lingual r, labial r, the r sound as a trill sound. These lie in between.

Now we must understand what actually lies behind this classification of sounds, which we have not arbitrarily established. It is not a schematic classification, but is taken from the organism of language. And there is something very significant behind it. We speak as a whole by shaping the air. Certainly, it is the common characteristic of all speech that we shape the air, but we shape the air in the most diverse ways.

Now, you can experience this shaping of the air in a magnificent way when you repeatedly form hm, hum, ham. In this, you have, I would say, the most general momentum of language. And once you have experienced this most general momentum of language, you will get the feeling with the sounds I have called plosives, i.e., d t b p g k m n, that when you make hm, you actually want to achieve the plosive at the end. You want to enter the thrust with the hm. You can feel that you want to make the air body into a closed figure. With everything that is written on this page — see diagram on page 354 — it is the case that, similar to the m, which does not yet show this as fully accomplished, but rather in status nascens, we want to enter into the closed form of the air, the air body, to form a figure. With all plosive sounds, we feel how we actually want to form a closed figure. And we can imagine that we want to continue.

By forming d, we actually want to form such a closed air figure in front of us: a kind of tube that is closed at the front, which we erect in front of us, we want to form with the d.

When we say b, it is actually as if we want to form a kind of small ship as a closed figure.

With k, we have the distinct feeling that we want to form something like a tower with our speech, a pyramid.

So we have a very clear feeling that we want to harden the air. And we would prefer it if the air would crystallize. When we pronounce the sounds, we actually have the feeling that body shapes are being projected into the air; and we are amazed that they don't fly around, because when we feel the language, we exert ourselves so strongly that the b and p, d and t, g and k are flying around, and the m are flying around like spirals and the n like some animal tails. We are actually amazed that this is not the case. For these plosive sounds are what, even though we form them in the air, continually strive toward the earth element. We work into the elemental earth with these plosive sounds; so that these plosive sounds correspond to the element earth. (See diagram.)

But this again has something extremely instructive about it and leads us to what can be extremely important for proper learning, because, you see, it is actually very beneficial for purifying speech and for making the organs of speech more flexible if we imagine a crystal shape when we say k, a tower-shaped crystal shape. This strong visualization supports us in saying k.

It is extremely beneficial if, while pronouncing m, we imagine a climbing plant winding its way up a stick, like a bindweed, while we pronounce m.

And it is very helpful when we say " to imagine woodruff, which has such a wreath of leaves up there; so we conjure up, as it were, what lies in the plosive sounds from the earth.

For example, you can increasingly bring out the inner configuration of the p by imagining the configuration of the sunflower, that bold, tall-growing flower with its overhanging, huge yellow blossoms that so strikingly stretch toward the center of its bloom. Inside, the p lies in an extraordinarily beautiful way.

Bringing out the plosive sounds from earthly forms is what really helps us in our speech. But everything we practice in this way can flow into the beautiful flow of language if we just let it flow, if we take a pyramid that actually represents a k and in which we live internally in language while we say k, and make it flow, make it dissolve. Then we let the k sound flow into the l sound, and you will see that what was initially very solid flows away like water. K, l = that flows away like water. And what interests you when you say the word wedge? A wedge that does not wedge anything, that does not flow in its movement, has no meaning, and a wedge has a k quite correctly, because it is a pyramid when you set it up. But what interests us about the wedge is that it flows. So this is a word of inner conciseness that is magnificent! And when you say “wedge” and feel what the wedge does, feel something splitting apart, and this transition into flow under obstacles, the obstruction again expressed by the “ei,” by the vowel, then you have something wonderful.

And so you can bring all plosive sounds into the correct, beautiful flow of speech when you combine them with an l. But you can also solidify the fluidity when you do the reverse procedure. Practice Diele. Diele: it flows wonderfully in the mouth. And if you want to do the reverse, that which is initially alive, then in turn lives beautifully into its form as something fluid into the solidifying earthiness: Lied. The song initially lives in the soul, then is formed in the poetry: Lied.

Learn to feel what lies in something like this. Take the plosive sound t, and let an l follow it somehow. There is a hard solidification in the t, but this hard solidification flows away. In the word valley, you have expressed it wonderfully, the running downwards, the pushing down.

Turn it around, take the liquid first and then make it solid, then you have it, if that is the valley, because you go through it when you think of what is inside as solid: a slat. First it is liquid, and then it becomes solid in the slat.

You see, in this way you come to feel your way into the secret of the word through the sound. Just try the same procedure we used with the wedge, but more in such a way that you are steering something in front of you that you can handle more easily than a wedge, which can only be handled with a hammer, something that is closer to humans, something more like a small boat that you steer in front of you. then you have an axe. You can clearly feel the difference between k and b – wedge and axe – in the whole of what that is.

But now go back. First have the fluid and then solidify it, so that it is not important for you to get the axe flowing, but to bring that which lives and breathes into a solid form, an envelope, then you have the body.

And so, in practicing the combination of plosive sounds with the wave sound l, you can wonderfully achieve that the language becomes closed and yet fluid, that your words are configured and yet the sentence flows so that one merges into the other.

Therefore, in the future, what is presented here, what one always achieves when combining plosives with the l, with the wave sound, should be used in connection with speech exercises and referred to as the plosive-wave in speech formation.

It should be a chapter that teaches how to limit the words in a sentence on the one hand, and on the other hand to make them flow in such a way that they represent the sentence as a stream. And that should be learned in the stop-wave. New expressions must be chosen for this purpose.

But now we come to the impact sounds and the l in the fluid, so that we can say: we have earth in the impact sounds, and in the l we have that which essentially means water, the element of water. This is recreated in language, so that water is in the l.

But suppose the water now becomes so thin that it becomes internally mobile, that we enter into the actual air, that the water evaporates more and more, becomes gas, wants to enter into the internal air form, then we no longer live contentedly with the internal flowing and waves, but then the air must tremble internally. And the air that we have at our disposal when speaking trembles internally in the r. The r corresponds to the element of air. Just feel how, when you have, let's say, a box. You open it and think there is a gift inside. You assume that what you are looking forward to, what causes inner movement in your soul, is inside. But it is not inside; there is nothing inside; everything that was once fluid = l evaporates. You move the liquid on your tongue, open it, and the merely trembling air meets you, and you burst out with the sound: empty! There you have it, quite vividly. You have felt the word through to the reverberation in the double ee: empty, which is particularly strong.

One cannot imagine that anything could be more adequate than, on the one hand, this gesture and this word empty. Both are to be examined very closely. But you can really learn a lot from such things. Especially for the free handling of what you need as an actor, you can learn an extraordinary amount.

And now imagine that you take this trembling and configure it in the air. You shape the trembling. You just needed to study the trumpet properly, not the metal, but what happens inside the trumpet while you're blowing. Just try it once, using very fine temperature gauges to see what happens inside the trumpet when the mere tremor turns into a formed tone figure. There are temperature differences everywhere inside the trumpet. This is expressed in the element of fire. That is why all wind instruments transition into the element of fire or heat, which we have when we pronounce the following letters with feeling: h ch j sch s f w. This lives in the element of heat. Therefore, when you begin with the h, you work out your warmth, you get rid of your warmth in the h, then you catch what you have brought out by feeling it as a solidification of your second human being: hm. Your warmth, which you bring to a solid state: hum, ham, and so on.

Now you can feel again how you can achieve what you want to put before you, what you want to live on in further life, what you want to put before you as something independently alive, when you practice directly in blowing sounds. Blowing sounds, you will be able to practice them in words that are not exactly common, because the living is not presented by humans in the same way as the solid, but nevertheless, you will find blowing sounds especially wherever something is represented in space in such a way that it lives, that it fluctuates. And there you can make interesting studies again. If you just want to express that something actually lives unpleasantly = crooked; it is already in the word crooked that it can always fall over rather than live: crooked.

But if one feels that one wants to have the mobile, the living, in the fixed, then a necessity will arise to want to set up the externally independent weaving and living, the living fluid. Now imagine that I have a figure, it is small at first, grows, grows, flows upwards. But if I want to express that what is actually life, weaving, is progressing in a line, then I say: slender. If I move from what represents life to the fluid and then come to what establishes this life in the line = slender, then I come back to the plosive sound k.

In particular, however, one can practice what one needs, especially in artistic speech formation. There you need the ability to speak in such a way that your speech flows over the auditorium. This does not need to be concentrated on the sounds and letters, but lies in the general character that one acquires for speaking in general.

For the actor, it will be particularly necessary to achieve this, to ensure that his words pass through the auditorium, that they live everywhere. They can achieve this—and knowing this is a special esoteric aspect of speech formation—by setting the air in motion through the transition to blowing sounds, i.e., by practicing: Reihe, reihen, reich, rasch, Reis—this transition does not like the ei—reif.

And if you want the L. sound itself to have a hypnotic effect on someone, you can do what the lawyer I spoke of yesterday did with his client; you can advise him to say: veiw. It has entered into this piece I spoke of yesterday with an extraordinarily fine sensibility. Sometimes, quite wonderful lawful things live instinctively in these things.

And so you see that one achieves the speech that shapes the sentence by learning to shape it with the earth-watery sounds, and what addresses is shaped with the air-fire sounds, with the trembling sound r and with the blowing sounds. Not that one has to express this with these sounds, but one can learn to shape a sentence properly so that it has an inner plastic power. By practicing connections in which the earth sounds and the water sound are present, one can learn to speak forcefully so that one can assume with a certain degree of certainty that it will be absorbed.

If, when practicing, one learns to do these exercises between the air sound r and the fire sounds, which are the blowing sounds—and the actor must learn both, he must speak beautifully and forcefully—then this is the way to learn to speak in a truly technically beautiful and forceful manner.

There is something else that is necessary for those who want to progress in speech formation. That is, they must acquire the ability to translate every sensation from the foreign into the intimate.

I will explain this to you in the following way. Take the feelings that some of you have on those days when the inner configuration of the air in this room is particularly noticeable. There are people who feel that it makes them uncomfortable. Now, let's take the most primitive sensation anyone can have. They have the sensation that it is hot in the hall, with all the secondary sensations that one can have there: hot, warm, let's just say warm. So: it is warm in the hall.

Now, anyone who has studied speech formation a little will know that the word warm can be said in many different ways in life. You know the nice anecdote that illustrates this: It's not what you say, it's how you say it. Little Itzig writes from afar to his father, who cannot read: Father, send me a guilder. The father cannot read and goes to the notary to have it read to him: Father, send me a guilder! [Roughly] What? That good-for-nothing rascal won't get anything from me if he writes like that! Did he really write that?

Well, but the father's heart does not want to accept this right away, so he goes to the pastor. The pastor reads it to him: Father dear, send me a guilder. — [Gently.] Did he really write that? — Yes, yes — Oh, I'll send him a guilder today, says the father. — Yes, you see, it's all in the tone.

Well, the word warm can be pronounced in many different ways. But, my dear friends, if you pronounce the word warm in many different ways, then you must also be able to do so. You have to learn to convey what you actually want to express emotionally in your pronunciation; you have to be able to convey that in your pronunciation. You have to learn that too. So imagine that someone feels this warmth here in this hall. I want to pick up on something that perhaps a number of you can feel right now: warmth.

Now, when you feel that, you can go back to the subjective. Imagine that someone who feels warm here closes their eyes, forgets that there are people in the hall, and says: It's whizzing. They call the feeling of warmth whizzing because they can also experience it that way when they return to the subjective. Just try to perceive how it whizzes differently. When it's cold, when you're freezing, it whizzes quite differently than when it gets warm. But let's assume that the feeling of warmth becomes almost a habit for you: it whizzes...

So warm = it whistles.

If you now train this purely in terms of sensation, you will learn to match this intonation of warmth to what you actually want to express. And so it is good to do such exercises as well.

Cold = it sparkles.

It bubbles, and indeed in the limbs. — And in this way, the more you form such things yourself, the better it is to translate an expression for a sensation into something that is more intimate, closer to you. So translating the more distant into the description of the more intimate gives the language its inner emotional tone.

So you have:

the inner emotional tone of language, the beautiful flow of language, the outward revelation, the penetrating persuasiveness of language.

These things can only really be learned by technical means. And the actor must learn them.

In the past, people instinctively knew a great deal about such things and were well aware of the spiritual, intellectual meanings of things. In the Pythagorean school, for example, it was customary to use particularly distinct rhythms to grasp the instinctive development of human beings and to promote it through education.

Suppose a trochaic or dactylic meter flows: Sing, immortal soul, the salvation of sinful humans. — Yes, you see, Pythagoras used such a rhythm, more in the recitative-singing style, in his school to curb the passions of passionate people. While he knew very well that an iambic flow tends to stir up emotions. These things were well known, just as it was known that music leads back to the gods of antiquity, the visual arts lead to the gods of the future, and the performing arts stand in the middle as that which captivated the spirits of the present.

But such attitudes must be developed. They must return to humanity so that art can be immersed in its proper element. And it is actually remarkable how instinctive this is.

You see, when the Austrian dialect poet, the Piarist monk Misson, wrote folk poetry, it is clear from everything else he did, if you know his biography, that he actually wanted to have a soothing effect with such poetry; that is why he did not choose iambic verse, but, even though he writes in dialect, the hexameter:

Naaz, iazn loos, töös, wàs a ta så, töös sàckt ta tai Våda.

Gottsnàm, wails scho soo iis! und probiast tai Glück ö da Waiden.

Muis a da sàgn töös, was a da sä, töös lås der aa gsàckt sai.

Ih unt tai Muida san àlt und tahoam, wóast as ee, schaut nix aussa.

Wås ma sih schint und rackert und plàckt und àbi ta scheert töös

Tuit ma für d’Kiner, was tuit ma nöd àlls, bald s’ nöd aus der Art schlàg’n!

We are a hard-working people and we are hard workers,

We grab hold of it, we find good, honest children...

and so on. One feels the soothing effect in it.

If one wants to lead directly to the spiritual, to guide one up to the spiritual movement, if one wants to lead from the physical to the spiritual, then one must use gentle language, but in iambic form.

And there you have one of the reasons why Goethe wrote his iambic dramas, why the mysteries are largely written in iambic meter, and so on. These are things that must be brought to life if we want to have drama schools again. And here one must know how language lives, how gesture lives, how everything that happens on stage has an effect in the wider context. We will continue with this tomorrow. As I said, I still have two lectures tomorrow and Tuesday on speech formation and dramatic presentation to round things off.