Education for Adolescents

GA 302

13 June 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture Two

In yesterday’s introduction I wanted to show the importance of the teacher’s understanding of the human being and of the school as organic unit. Everything else really depends on this understanding. Today I shall touch on several issues that may then be further developed.

If we wish to have a correct picture of the human being, what really matters is that we rid ourselves of all the prejudices in the current scientific world conceptions. Most people today—even those who are not materialists—are convinced that the processes in logical thinking are carried out by the soul, an inner organism, and that the brain is used as a kind of mechanism for carrying out these processes. All logical functions and processes, they say, are cerebral. The attempt is then made to explain these processes in three stages—the forming of mental images, judgments, and conclusions. It is true, is it not, that we must apply these processes in our lessons, that we must teach and practice them?

We have been so conditioned to this way of thinking that all logic is a function of the head that we have lost sight of the real, the actual nature of logic. When we draw people’s attention to the truth of the matter they demand proofs. The proof, however, lies in unprejudiced observation, in discovering the development of logic in the human being. Of the three stages—mental images, judgments, conclusions—only in the first is the head involved. We ought to be conscious of this: The head is concerned only with the forming of mental images, of ideas, and not with judgments or conclusions.

You may react by saying that spiritual science is gradually dismissing the head and diminishing its functions. But this is in accordance with the truth in its most profound meaning. The head really does not do all that much for us during our life between birth and death. True, in its outer appearance, its physical form, it is certainly the most perfect part of our body. But it is so because it is a copy of our spiritual organism between death and rebirth. It is, as it were, a seal, an impress of what we were before birth, before conception. Everything that was spirit and soul impressed itself on the head, so that it represents the picture of our prenatal life.

It is really only the etheric body—besides the physical—that is fully active in the head. The astral body and the I fill the head, but they merely reflect their activity in it; they are active for their own sake and the head merely reflects this. In the shape of the head we have a picture of the supersensible world. I indicated as much during last year’s lectures when I drew your attention to the fact that we are really carrying our heads as special entities on the top of our bodies. I compared the body to a coach or horse and the head to the passenger or rider. The head is indeed separated from the world outside. It sits, like a parasite, on the body; it even behaves like a parasite. We really must get away from the materialistic view of the head that attaches too much importance to it. We need our head as a reflecting apparatus, no more. We must learn to see the head as a picture of our prenatal spirit and soul organism.

The forming of mental images and ideas is indeed connected to the head. But not our judgments. These are actually connected to arms and hands. It is true—we judge with our arms and hands. Mental images, ideas we form in our heads. But the processes leading to judgments are carried out by the mechanism of arms and hands. The mental images of a judgment do, as its reflection, take place in the head.

You can develop a feeling for this distinction and then recognize its important didactic truth. You can tell yourselves that the task of our middle organism is to mediate the world of feelings. The rhythmical organism is essentially the basis for the mediation of feelings. Judgments are, you will agree, deeply related to feelings, even the most abstract of judgments. When we say “Carl is a good boy,” this is a judgment, and we have the feeling of confirmation. The feeling of confirmation or negation—any feeling actually that expresses the relation between predicate and subject—plays a major role in judgments. It is only because our judgments are already strongly anchored in our subconscious that we are not aware of our feelings’ participation in them.

There takes place for us as human beings, inasmuch as we judge, a phenomenon that we must understand. The arms, although in harmony with the rhythmic organism, are at the same time liberated from it. In this physical connection of the rhythmical organism with the liberated organism of the arms, we can see a physical, sense-perceptible expression of the relation between feelings and judgments.

In considering conclusions, the drawing of conclusions, we must understand the connection to legs and feet. Our contemporary psychologists will, of course, ridicule the idea that it is not the head that draws conclusions but the legs and feet. But it is true. Were we, as human beings, not oriented toward our legs and feet, we could never arrive at conclusions. What this means is that we form ideas and mental images with the etheric body, supported by the head organism; we make our judgments—in an elementary, original way—with our astral body, supported by our arms and hands; and we draw conclusions in our legs and feet—because we do this with our ego, and the ego, the I, is supported by legs and feet.

As you can thus see, the whole of the human being participates in logic. It is important to understand this participation. Our conventional scientists and psychologists understand but little of the nature of the human being because they don’t know that the total human being is employed in the process of logic. They believe that only the head participates in it. We must now understand the way in which the human being, as a being of legs and feet, is placed on the earth—a way quite different from that of the human head being. We can illustrate this difference in a drawing.

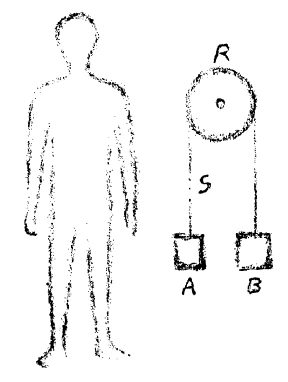

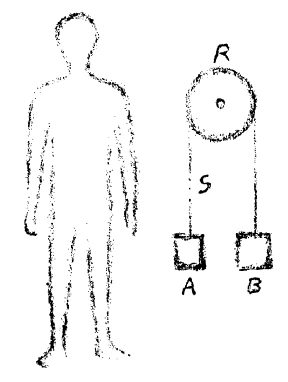

By imagining the outline of the human being we may arrive at the following concept. Let us assume that the person in the diagram is lifting a weight by hand, in our case a heavy object weighing one kilogram. The object is lifted by hand. Let us now ignore the person and, instead, tie the object (A) to a rope, pass the rope over a pulley, and tie another object of either identical or heavier weight to the other end (B). If B happens to be heavier, it will draw the original weight (A) up. We have here constructed a mechanical device the achievement of which is identical to that of hand and arm. I can replace hand and arm with a mechanical device—the result is the same. I unfold my will and, in so doing, I accomplish something that can equally be achieved by some mechanical device, as shown in the illustration.

What you can see in this diagram is a happening that is quite objective. The employment of my will does not alter the outer picture. With my will I am fully placed into the objective world. I impart myself into the objective world; unfolding my will, I no longer differentiate myself from it.

What I have demonstrated can be observed especially clearly when I take a few steps or use my legs for something else. What the will accomplishes during the use of my legs and feet is a process that is quite objective, something that takes place in the world outside. As seen from without, there is no difference between a mechanical process and my own personal effort of will. All my will does is to direct the course of events. This is most strongly the case when I employ functions that are connected with my legs and feet. I am then really outside myself, I flow together with the objective world, I become part of it.

The same cannot be said of the head. The functions of the head tear me away from the world. What I call seeing and hearing, what ultimately leads to the forming of ideas and mental images, cannot in this objective way impart itself to the world outside. My head is not part of that world; it is a foreign body on earth, a copy of what I was before I descended to earth.

Head and legs are extreme opposites and, between them, in the center—because there the will is already active, but in conjunction with feelings—between them we have the organization of arms and hands. I ask you to keep in your mind this picture of the human being—through the head, as it were, separated from the earth, having brought the head from the spiritual world as a witness, the proof of belonging to the spiritual world. One imparts oneself into the physical world by adapting the organs of will and the feelings to the outer laws, to environment and institutions. There is no sharp boundary between outer events and the accomplishments of the will. But a sharp boundary is always drawn between outer events and the ideas and mental pictures mediated to us through the head.

This distinction can give us an even better understanding of the human being. The head develops first in the embryo. It is utter nonsense to regard it as being merely inherited. Its spherical shape tells you that it is truly a copy of the cosmos, whose forces are active in it. What we inherit enters the organism of our arms and legs. There we are our parents’ children. They relate us to the terrestrial forces. But our heads have no access to the earth’s forces, not even to fertilization. The head is organized by the cosmos. Any hereditary likeness is caused by the fact that it develops with the help of the other organism, is nourished by the blood that is affected by the other organism. But it is the cosmos that gives the head its shape, that makes it autonomous and individual. Above all, the work of the cosmos—inasmuch as it is connected to the head—can be seen in those things that are part of the nerve-sense organism. We bring our nerve-sense organism with us from the cosmos, allowing it to impart itself into the other organism.

This knowledge is important because it helps us to avoid subscribing to the nonsensical idea that we are the more spiritual the more we ignore the physical and to avoid talking in abstractions about spirit and soul. We become truly spiritual when we learn to see the connection between the physical/corporeal and the soul and spirit, when we understand that our head is a product of the cosmos, is organized by it, makes us part of it. The organism of our legs is inherited; there we are our parents’ and grandparents’ descendants.

This knowledge, being true, will affect our feelings, while all the current concepts—be they about spirit or matter—are abstract, in no way related to reality. They leave us cold, cannot stir our feelings. I would therefore like to ask you to take to your hearts, to ponder deeply, and to develop for your educational work the fact that there is really no difference whether the human being is regarded as a physical/corporeal being or as a being of spirit and soul. Once we have learned to observe spirit and soul in the correct way we shall see them as creative elements from which flows the physical/corporeal. We shall recognize spirit and soul in their creative activity. And if, as artists, we reflect on this activity in the right way, we shall gradually lose sight of the material altogether as it becomes spirit all by itself. The physical/corporeal transforms into spirit in our correct imagination.

When one stands firmly on the ground of spiritual science, of anthroposophy, it no longer matters if one is a materialist or a spiritualist. It really doesn’t matter. The harm done by materialism is not the study of material phenomena. If this study were performed thoroughly, the phenomena would transform into spirit and all the materialistic concepts would be recognized as absurdities. The harm done is the feeble-mindedness that results when we do not complete thought processes, when we do not concentrate enough on what the senses perceive. We thus lose sight of reality. If we were to pursue thoughts about the material world to the end, we would arrive at the picture, the idea of the spirit.

As for spirit and soul, as long as we enter their reality when we reflect on them, they will not remain as the abstractions we are given by our current sciences but will assume form, will become visible. Abstract understanding becomes an artistic experience that will ultimately result in our seeing spirit and soul as material, tangible reality.

Be one a materialist or a spiritualist both perspectives will lead to the same result, provided the thought process is completed. Again, it is not the spirit that is the problem in spiritualism but rather this uncompleted thought process that so easily turns the spiritualist into an idiot, a nebulous mystic, a person who causes confusion and who can only vaguely come to grips with reality.

There is yet another essential and important task for you. Equipped with a sound understanding of the nature of the child, you must develop an eye for distinguishing the child with a predominant cosmic organism from the one with a predominant terrestrial/physical organism. The former will have a plastically formed head, the latter a plastically structured trunk and, especially, limbs.

What now matters is to find the appropriate treatment for each. In the more earthly child, the hereditary forces are playing a major role; they permeate the entire metabolic limb system in an extraordinarily strong way. Even when the child does not appear to be melancholic, there is, nonetheless, alongside the apparent temperament a nuance of melancholy. This is due to the child’s earth nature, the “earthiness” in the child’s being.

When we notice this trait in a child, we shall do well to try to interest him or her in music that passes from the minor to the major mood, from the melancholic strains of the minor to the major. The earthly child especially can be spiritualized by the movements demanded by music and eurythmy. A child with a distinct sanguine temperament and delicate melancholic features can easily be helped by painting. And even if such a child appears to have but little talent for music or eurythmy, we should still try our best to develop the disposition for it that is certainly there.

A child with a distinctly pronounced head organism will benefit from subjects such as history, geography, and the history of literature. But care must be taken not to remain in the contemplative element but, as I already pointed out yesterday in another context, to evoke moods, feelings, tension, curiosity that are again relaxed, satisfied, and so on.

Again, it is a matter of habitually seeing the harmony between spirit and body. The ancient Greeks had this knowledge, but it got lost. They really always saw in the effects of a work of art on human beings something they then also applied to the physical. They spoke of the crisis in an illness, of catharsis, and they spoke in the same way of the effects of a work of art and of education. The Greeks observed the processes that I described yesterday, and it is up to us to rediscover them, to learn to unite soul and spirit with the physical/corporeal in our thinking.

It is thus important that we use all our own temperamental energies, in order to teach history with a strong personal accent. Objectivity is something the children can develop later in life. To worry about objectivity, when we tell them about Brutus and Caesar, at the expense of expressing the feeling engendered in us during the dramatic presentation of their differences, their polarities—this would be bad teaching. As teachers, we must be involved. We do not need to wax passionate, to roar and rage, but we do need to express at least a delicate nuance of sympathy or antipathy toward Caesar and Brutus in our characterization. The children must be stimulated to participate.

History, geography, geology, and so on must be taught with real feeling. The latter subject is especially interesting—to feel deeply about the rocks beneath the earth. Goethe’s essay on the granite can here be of great help. I strongly recommend it to you. Read it with feeling, in order to see how a person could humanly relate—not merely in thinking, but in his whole being—to the primal father, the age-old, holy granite. This approach must, of course, then be extended to other subjects.

If we cultivate these responses in ourselves, we shall also make it possible for the children to experience and participate in them. This is naturally a more difficult approach, as it takes greater effort. But our teaching will be alive, a living experience. Believe me, everything we mediate to the children via feelings allows their inner life to grow, while an education that consists of mere thoughts and ideas is devoid of life, remains dead. Ideas and thoughts are no more than mirror images. With them we merely address the head, whose value lies in its connection with the past, its time in the spiritual world. When we give the children images and ideas that are made living through our strong feelings, we make a connection to what is significant for the earth, to the elements contained in the blood.

Let me give you an example. It is absolutely necessary for us to develop the appropriate feeling for the hostile, destructive forces in an airless space. The more graphically we show this—after the air has been pumped out—the more dramatically we can describe this terrible airless space, the more we shall achieve. In earlier times people referred to it as horror vacui. They experienced this horror streaming from it; their language contained it, and we must learn to discover this feeling again. We must learn to see a connection between an airless space and a thin, dried up person. Shakespeare indicated this in Julius Caesar:

Let me have men about me that are fat;

Sleek-headed men and such as sleep o’nights:

Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look;

He thinks too much: such men are dangerous.

It is the well-padded whom we trust, rather than the lean, skinny, bald-headed person with cold intellect. We must feel this relation of a lean person or a spider to airless space. Then we shall be able to pass on to the children, through imponderables, the cosmic feeling that must be an integral part of the human being.

Again and again, when speaking of education, we must emphasize the necessity of connecting the totality of the human being to the objective world, because it is only then that we can bring a healthy element also to those aspects in education that are so harmfully influenced by materialistic thoughts. We cannot, my dear friends, be as outspoken as Herr Abderhalden who—after having been invited to a eurythmy performance where in my introduction I also mentioned the hygienic and other aspects of physical education—said: “As a physiologist I cannot see anything in physical education that is physiologically justified. On the contrary, physical education is, in my opinion, the most harmful activity imaginable; it has no educational value whatsoever. It is a barbarity.”

We cannot afford to be so direct. We would be attacked from every side, as happens today. It is so, isn’t it, when you really think about it, that all the exercises and activities of physical education, wherein the worst of materialistic concepts are applied to the physical body, have become idols, fetishes—be they systems concentrating on the strongly physical, the superphysical, or the subphysical; be it the Swedish method or the German. What the systems and methods have in common is the belief that the human being is no more than a physical organism—a belief resulting from the very worst ideas developed by the age of materialism, not in accord with the thoughts I have outlined.

The exercises are generally based on an assumption describing the ideal posture for the human being—the correct curvature of the spine, the form of the chest, the manner of moving the arms and hands. What we actually get from the exercises is certainly not a human being but merely the picture these people have made themselves of the human being. No wonder there are so many diagrams in the manuals. This picture of the human being lends itself to being modeled in a papier-mâché figure. Everything that is said of the human being in Swedish gymnastics can be found in such a papier-mâché doll. The living human being can then be used like a sack and made to imitate the lifeless dolls. The real human being is ignored, is lost sight of in such practices. All we have are papier-mâché figures.

In spite of the fact that they have become so popular and influential, these practices must be seen as infamous, really quite reprehensible, because of this exclusion of the real human being. The human being is theoretically excluded in the sciences; in modern gymnastics the human being is practically excluded, reduced to a papier-mâché figure. Such practices should never find their way into education. In good physical education, the students should only carry out movements and assume postures that they can also actually experience within. And they do experience them.

Let’s take a look at the breathing processes. We must know that we must bring the children to the point where the breathing- in bears a faint resemblance to tasting some favorite food. This experience should not go so far as to the actual perception of taste but merely to a faint resemblance of it; the freshness of the world ought to be experienced when breathing in. We should try to get the child to ask: “What is the intrinsic color of the air I am breathing in?” We shall indeed discover that as soon as breathing is correctly experienced, the child will have the feeling that “it is greenish, really actually green.” When we have brought a child to the point of experiencing inbreathing as greenish we have accomplished something. Then we shall also always notice something else: that the child will ask for a specific posture when breathing in. The inner experience stipulates the correct corresponding posture, and the right exercises will follow from it.

The same procedure will lead to the experience of the corresponding feeling in breathing out. As soon as the children, when breathing out, can feel that they really are fine, efficient boys and girls, as soon as they experience themselves as such, feel their strength, ask to apply their strength to the world outside, then they will also experience, in a way that is healthy and appropriate to their age, the corresponding abdominal movement, the movement of the limbs and the bearing of the head and arms. This rich feeling during breathing out will induce the children to move correctly.

Here the human being is employed. We can see the human being before us, no longer allowed to be a sack, imitating a papier-mâché figure. We are moving in accordance with the soul that then pulls the physical body after it. We adapt the physical movements to the children’s needs, to their inner, soul and spirit experience.

In the same way, we should encourage the inner experience the children’s physical nature asks for in other areas—in the movements of arms and legs, in running, and so forth. We can thus really connect physical education directly to eurythmy, as it should be connected. Eurythmy makes soul and spirit directly visible, ensouls and spiritualizes everything that moves in us. It makes use of everything human beings have developed for themselves during their evolution.

But—also—the physical can be spiritually experienced. We can experience our breathing and metabolism if we advance far enough in our efforts. It is possible to do this—to advance to the point that we can experience ourselves, including our physical organism. And then, what the children are—on a higher level, I would say—confronting in eurythmy can pass into physical education. It is certainly possible to connect the two activities, to build a bridge from the one to the other. But this kind of physical education should be based on the development of movements not from the mere experience of the physical/corporeal but rather from the experience of soul and spirit, by letting the children adapt the physical/corporeal to their experiences.

Of course, in order to achieve this we ourselves must learn a great deal. We must first work with these ideas before we apply them to both ourselves and especially before we apply them to our teaching. They don’t easily impress themselves on our memory. We are not unlike a mathematician who cannot remember formulae or theorems but who, at a given moment, is able to redevelop them. Our situation is the same. We must develop these ideas about the total human being—spirit, soul, and body—and we must always make them livingly present. Doing so will stand us in good stead. By working out of the totality of the human being we can have a stimulating effect on the children.

Again and again you will find that when you have spent long hours in preparing a lesson, when you have grappled with a subject and then enter the classroom, the children will learn differently than they would when taught by a “superior” lecturer or instructor who spent as little time as possible in preparation. I actually know people who on their way to school quickly read up the required material. Indeed, our education and teaching are deeply affected by the way we grapple not only with the immediate subject matter but also with all the other things connected to skills and methods. These things, too, should be worked and grappled with.

There are spiritual connections in life. If we have first heard a song in our mind, in the spirit, it will have a greater effect on the children when we teach it to them. These things are related. The spiritual world works in the physical. This activity, this work of the spiritual world, must be applied especially to education and didactics. If, for example, during the preparation for a religion lesson, the teacher experiences a naturally pious mood, the lesson will have a profound effect on the children. When such a mood is absent, the lesson will be of little value to them.

Zweiter Vortrag

Ich wollte gestern in den einleitenden Worten begreiflich machen, wie sehr es darauf ankommt, daß man sich in das ganze Unterrichten hineinstellt mit einer Grundempfindung über den Menschen oder von dem Menschen und gewissermaßen von dem Schulwesen als einem einheitlichen Organismus. Und ich möchte heute einiges Prinzipielle vor Sie hinstellen, auf dem wir dann weiter werden aufbauen können.

Es handelt sich ja so sehr darum, wenn man wirklich das Wesen des Menschen in der richtigen Weise sich vergegenwärtigen will, daß man Abschied nimmt von mancherlei Vorurteilen, die die neuere wissenschaftliche Weltanschauung schon einmal mit sich heraufgebracht hat. Wenn Sie heute irgend jemanden sprechen hören über den Menschen und dasjenige, was er logisch unternimmt, was er als Logik entfaltet, dann werden Sie die Ansicht hören, daß der Mensch durchaus selbst wenn also die Leute nicht Materialisten sind — mit einem seelischen Organismus denkt, daß er die logischen Funktionen mit dem seelischen Organismus durchführt und zu diesem Durchführen der logischen Funktionen als eine Art Mechanismus sein Gehirn braucht. Man denkt sich, daß alle Denkfunktionen, alle logischen Verrichtungen an das Gehirn gebunden seien. Man versucht dann die logischen Verrichtungen zu unterscheiden in das Vorstellen, in das Urteilen, in das Schließen, Schlüsse machen. Nicht wahr, es ist ja so, daß wir auch im Lehrgang schon mit den Kindern vorstellen, urteilen, schließen, Schlüsse bilden üben müssen.

Nun hat sich diese Anschauung, daß alles Logische gewissermaßen eine Kopffunktion sei, so festgelegt, daß dem Menschen allmählich der unbefangene Blick verlorengegangen ist für die Wirklichkeit dieses Gebietes. Und wenn man von dieser Wirklichkeit spricht, werden die Leute sagen: Beweise mir das. — Aber der Beweis liegt wirklich in einem unbefangenen Beobachten, in einem Daraufkommen, wie sich dieses Logische beim Menschen entfaltet. Von den logischen Funktionen: Vorstellen, Urteilen, Schließen, ist eigentlich nur das Vorstellen eine wirkliche Kopffunktion. Und dessen sollen wir uns sehr bewußt werden, daß eigentlich nur das Vorstellungenbilden, nicht aber das Urteilen und das Schließen, eine Kopffunktion ist.

Sie werden sagen: Allmählich wird der Kopf durch die Geisteswissenschaft ganz außer Gebrauch gesetzt. — Aber das ist tatsächlich etwas, was im tiefsten Sinn der Wirklichkeit entspricht, denn wir haben eigentlich an unserem Kopf nicht so außerordentlich viel als Menschen im Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Der Kopf ist äußerlich in seiner Form, in seiner physischen Form allerdings das Vollkommenste, das wir haben. Aber er ist das aus dem Grunde, weil er eigentlich ein Abbild ist unserer geistigen Organisation zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Er ist in gewissem Sinn ein Siegelabdruck desjenigen, was wir waren vor unserer Geburt, vor unserer Empfängnis. Alles dasjenige, was geistig-seelisch ist, hat sich in unserem Kopf abgeprägt, so daß er ein Bild unseres vorgeburtlichen Lebens vorstellt. Und eigentlich voll tätig ist in unserem Kopf nur der Ätherleib außer dem physischen Leib. Die anderen Wesensglieder, der astralische Leib und das Ich, erfüllen den Kopf, aber sie spiegeln darin ihre Tätigkeit; sie sind für sich tätig und der Kopf spiegelt nur ihre Tätigkeit ab. Dieser Kopf ist überhaupt, von außen, als ein Bild der übersinnlichen Welt vorhanden. Ich habe darauf in dem Kurs des vorigen Jahres hingedeutet, indem ich Sie darauf aufmerksam machte, daß wir den Kopf eigentlich als eine besondere Wesenheit auf unserem menschlichen Organismus tragen. Wir können den übrigen menschlichen Organismus ansehen wie eine Art Kutsche und den Kopf als denjenigen, der in dieser Kutsche fährt, könnten ihn auch ansehen, wenn wir den übrigen Organismus als Pferd ansehen, als Reiter auf diesem Pferde. Er ist tatsächlich abgesondert von diesem Zusammenhang mit der übrigen irdischen Außenwelt. Er sitzt auf dem Körper wie ein Parasit darauf und benimmt sich auch wie ein Parasit. Es ist schon notwendig, daß man die materialistische Anschauung, als ob wir vom Kopf so außerordentlich viel hätten — wir brauchen ihn als Spiegelungsapparat —, daß man diese Ansicht aufgibt. Das ist schon notwendig. Wir müssen den Kopf ansehen lernen als ein Bild unserer vorgeburtlichen geistig-seelischen Organisation.

Aber das Vorstellen ist ja tatsächlich an den Kopf gebunden, nicht aber das Urteilen. Das Urteilen ist eigentlich an den mittleren Organismus und namentlich an die Arme und Hände gebunden. Wir urteilen eigentlich in Wirklichkeit mit den Armen und Händen. Vorstellen tun wir mit dem Kopf. Wenn wir also den Inhalt eines Urteils vorstellen, so geht das Urteilen selbst in dem Mechanismus der Arme und Hände vor sich, und nur das vorstellungsgemäße Spiegelbild geht im Kopfe vor sich. Sie werden da ja auch innerlich begreifen können und es dann als eine wichtige didaktische Wahrheit durchschauen. Sie können sich sagen: der mittlere Organismus ist eigentlich dazu da, die Gefühlswelt zu vermitteln. Der rhythmische Organismus des Menschen ist im wesentlichen der Sitz der Gefühlswelt; er ist eigentlich dazu da, die Gefühlswelt zu vermitteln. Das Urteilen hat doch eine tiefe Verwandtschaft mit dem Fühlen. Selbst das abstrakteste Urteil hat eine Verwandtschaft mit dem Fühlen. Wenn wir ein Urteil fällen: Karlchen ist brav -, das ist ein Urteil, dann haben wir das Gefühl der Bejahung; und es spielt eine große Rolle im Urteil das Gefühl der Bejahung und Verneinung, überhaupt das Gefühl, das im Prädikativen, im Verhältnis zum Subjektiven ausgedrückt wird. Und nur weil das Gefühl so stark schon dem Halbbewußten angehört, achten wir nicht darauf, wie sehr das Gefühl am Urteilen beteiligt ist. Nun ist beim Menschen, weil er vorzugsweise ein urteilendes Wesen sein soll, sein Armorganismus in Einklang gebracht mit dem rhythmischen Organismus, aber in gleicher Zeit von dem fortdauernden rhythmischen Organismus befreit. So haben wir da auch in der physischen Verbindung zwischen rhythmischem Organismus und dem befreiten Armorganismus, physisch-sinnlich die Art ausgedrückt, wie das Gefühl mit dem Urteil zusammenhängt.

Das Schließen, das Schlüsse bilden, hängt nun zusammen mit Beinen und Füßen. Natürlich werden Sie heute ausgelacht, wenn Sie einem Psychologen sagen, man schließt nicht mit dem Kopf, sondern man schließt mit den Beinen, mit den Füßen, aber das letztere ist doch die Wahrheit, und würden wir als Mensch nicht auf Beine und Füße hin organisiert sein, würden wir eben nicht Schlüsse bilden können. Die Sache ist so: Vorstellen tun wir mit dem Ätherleib, und der hat seinen Rückhalt an der Hauptesorganisation, aber urteilen tun wir — also in ursprünglicher elementarischer Weise — mit dem astralischen Leib, und der hat seinen Rückhalt an Armen und Händen für das Urteilen. Schließen mit den Beinen und Füßen, denn schließen tun wir mit dem Ich, das hat dabei den Rückhalt an den Beinen und Füßen.

Sie sehen daraus, es ist der ganze Mensch beteiligt an der Logik. Und das ist sehr wichtig, daß man sich da hineinfindet, daß man den ganzen Menschen an der Logik beteiligt denkt. Die neuere Erkenntnis weiß sehr wenig vom Menschen, weil sie eben nicht weiß, daß der ganze Mensch an der Logik beteiligt ist; sie glaubt, daß er immer nur mit dem Kopf hantiert. Nun steckt der Mensch, insofern er Beineund Füßemensch ist, in einer ganz anderen Weise in der irdischen Welt darinnen als der Kopfmensch. Das können Sie sich etwa anschaulich machen durch folgendes Bildchen (siehe Zeichnung). Stellen Sie sich schematisch den Menschen vor, so können wir folgendes als Begriff bilden: Nehmen wir an, dieser Mensch hebt hier mit dieser Hand irgendein Gewicht (A), sagen wir ein Kilogewicht. Das hebt er mit seiner Hand auf. Wir wollen jetzt absehen davon, daß dieser Mensch das Kilogewicht aufhebt mit der Hand, sondern wir wollen hier (s) ein Seil anbringen, hier (R) eine Rolle und das Seil über die Rolle darübergehen lassen und hier (B) wiederum ein Kilogewicht aufhängen oder vielleicht ein etwas schwereres Gewicht. Wenn wir ein etwas schwereres Gewicht als das Kilogewicht haben, so zieht dieses durch diese Vorrichtung das andere hinauf. Da haben wir eine mechanische Vorrichtung in die Welt hineingestellt, die ganz dasselbe tut, wie wenn ich den Arm gebrauche und das Gewicht heraufhebe. Nicht wahr, wenn ich mit dem Arm das Gewicht heraufhebe um irgendein Stück, so ist das genau dasselbe Verrichten wie das, das dadurch geschieht, daß ich das schwerere Gewicht anhänge und das andere hinaufziehen lasse. Ich entfalte meinen Willen, und damit tue ich etwas, was sich da vollziehen kann nach demselben Bilde, was sich vollziehen kann mit rein mechanischen Vorrichtungen. Das, was hier gesehen werden kann an diesem Kilogewicht, dieses Hinaufziehen, das ist ein ganz objektives Ereignis. Wenn mein Wille eingreift, so verändert sich das äußere Bild nicht. Ich stehe dann mit meinem Willen ganz in der objektiven Welt drinnen. Ich schalte mich in die objektive Welt ein. Ich unterscheide mich nicht mehr von der objektiven Welt, indem ich meinen Willen entfalte.

Dasjenige, was ich da ausführe, zeigt sich besonders deutlich, wenn ich nun gehe oder überhaupt mit den Beinen etwas mache. Wenn ich gehe und mit den Beinen etwas mache, so ist dasjenige, was der Wille vollzieht, ein ganz objektiver Vorgang; das ist etwas, was in der Welt geschieht. In der Willensentfaltung ist es zunächst für den Anblick des äußeren Ereignisses im Grunde genommen gleichgültig, ob nur ein mechanischer Vorgang sich abspielt, oder ob mein Wille eingreift. Mein Wille dirigiert nur den Verlauf mechanischer Vorgänge. Das ist am stärksten vorhanden, wenn ich eben Funktionen entfalte, die sich mit Beinen und Füßen abspielen. Da bin ich im Grunde genommen aus mir heraußen, da fließe ich ganz zusammen mit der objektiven Welt, da bin ich ganz ein Teil der objektiven Welt.

Vom Kopf kann ich das nicht sagen. Die Funktionen des Kopfes reißen mich aus der Welt heraus; ich kann dasjenige, was ich Sehen, Hören nenne, was zuletzt zum Vorstellen führt, nicht in dieser objektiven Weise in die Welt hineinstellen. Mein Kopf gehört gar nicht in die Welt hinein. Er ist ein Fremdprodukt in dieser irdischen Welt, er ist das Nachbild dessen, was ich war, bevor ich auf die Erde hinuntergestiegen bin. Die äußersten Extreme sind der Kopf und die Beine, und in der Mitte drinnen steht — weil da der Wille schon wirkt, aber namentlich wirkt mit dem Gefühl -, dazwischen steht die Arme- und Händeorganisation. Bitte, denken Sie an das, wie da der Mensch durch seinen Kopf eigentlich abgesondert ist, wie er den Kopf hereinträgt aus einer geistigen Welt, wie der Kopf schon physisch eigentlich der Zeuge ist davon, daß der Mensch einer geistigen Welt angehört, und wie der Mensch sich hereinzwängt in die physische Welt dadurch, daß er sich mit seinen Gefühls- und Willensorganen eben den ganzen äußeren Einrichtungen, den äußeren Gesetzen anpaßt. Man kann keine scharfen Grenzen einzeichnen zwischen dem äußeren Geschehen und meinem Willensgeschehen. Man muß aber immer eine scharfe Grenze angeben zwischen den äußeren Vorgängen und dem, was durch den Kopf an Vorstellen vermittelt wird.

Da können Sie, ich möchte sagen, die Leitlinie ziehen, um den Menschen noch besser zu begreifen. Der Mensch wird ins embryonale Leben hereinversetzt, indem er ja zuerst die Kopforganisation ausbildet. Es ist ein Unsinn, zu denken, daß die Kopforganisation nur eine Vererbungsgeschichte ist. Die Kopforganisation ist — sie ist Ja auch sphärisch — durchaus eine Nachbildung des Kosmos, und die Kräfte des Kosmos wirken da herein. Dasjenige, was der Mensch durch die Vererbungsströmung erhält, das geht durch seine Arm- und Beinorganisation. Durch diese nur ist er eigentlich ein Kind seiner Eltern. Durch diese hängt er mit den irdischen Kräften zusammen; denn der Kopf ist gar nicht den irdischen Kräften zugänglich, auch nicht der Befruchtung. Der Kopf wird hereinorganisiert aus dem Kosmos. Und wenn der Kopf auch Ähnlichkeiten zeigt mit den Eltern, so rührt das davon her, daß er sich an dem übrigen Organismus entwickelt, von dessen Blut gespeist wird, in das der übrige Organismus hineinwirkt. Aber dasjenige, was der Kopf für sich ist in seiner Formung, das ist ein Ergebnis des Kosmos. Und ein Ergebnis des Kosmos ist vor allen Dingen dasjenige - insofern als es an den Kopf gebunden ist —, was mit dem Nerven-Sinnesorganismus zu tun hat. Denn den NervenSinnesorganismus tragen wir auch aus dem Kosmos herein und lassen ihn dann in den übrigen Organismus einwachsen.

Es ist schon durchaus wichtig, daß man solche Dinge ins Auge faßt, denn man lernt dadurch in sich selber den Unfug abschaffen, als ob man besonders geistig, spirituell würde, wenn man nur ja nicht vom Körperlich-Leiblichen spricht und nur immer von etwas abstrakt Geistig-Seelischem. Man wird im Gegenteil recht geistig, recht spirituell, wenn man die Zuordnung des Leiblich-Körperlichen zu dem Seelisch-Geistigen in der richtigen Weise zu durchschauen vermag, wenn man zu durchschauen vermag: in bezug auf den Kopf bist du hereinorganisiert aus dem Kosmos; in bezug auf den Beinorganismus bist du ein Kind deiner Eltern und Voreltern. Und diese Erkenntnisse, die gehen dann sehr stark über in das Gefühl, denn sie sind Erkenntnisse von Wirklichkeiten, während die Erkenntnisse, die durch die heutigen Abstraktionen übermittelt werden — gleichgültig, ob man damit diese Abstraktionen meint oder die Beschreibung des Materiellen -, im Grunde genommen gar nichts mit dem Wirklichen zu tun haben. Daher können sie uns auch nicht empfindungsgemäß anregen. Dasjenige, was so ins Wirkliche hineingeht, das regt uns auch empfindungsgemäß an, und daher machen Sie sich mit einem Gedanken recht gut bekannt und versuchen Sie, ihn pädagogisch tief auszubilden. Das ist nämlich der: es ist eigentlich einerlei, ob man den Menschen in bezug auf sein Physisch-Körperliches betrachtet, wenn man ihn richtig betrachtet, oder in bezug auf sein Geistig-Seelisches. Wenn man das Geistig-Seelische in richtiger Weise betrachten lernt, so lernt man es als ein Schöpferisches kennen, das aus sich herausfließen läßt das Physisch-Körperliche. Man sieht es am Schaffen, das Geistig-Seelische. Und wenn man das künstlerisch in der richtigen Weise betrachtet, dann ist es so, daß man allmählich die Materialität ganz verliert, und es wird ganz von selber ein Geistiges. Das Physisch-Körperliche verwandelt sich im richtigen Vorstellen in ein Geistiges.

Steht man auf dem Boden der Geisteswissenschaft, der Anthroposophie, so ist es einerlei, ob man Materialist oder Spiritualist ist. Es kommt gar nicht darauf an. Die Schädlichkeit des Materialismus besteht nicht darinnen, daß man die materiellen Erscheinungen und Wesenheiten kennenlernt; denn lernt man sie gründlich kennen, dann verliert man die albernen materialistischen Begriffe, und das Ganze wandelt sich in Geistiges um. Die Schädlichkeit besteht darinnen, daß man leicht schwachsinnig wird, wenn man sich auf das Materielle richtet und nicht zu Ende denkt und nicht auf dasjenige geht, was man durch die Sinne sieht. Dann hat man keine Wirklichkeit. Man denkt das Materielle nicht zu Ende; denn denkt man es zu Ende, dann wird es in der Vorstellung ein Geistiges. Und wenn man das GeistigSeelische betrachtet, so bleibt es auch nicht, wenn man in seine Wirklichkeit eintritt, jenes Abstrakte, das uns so leicht in der heutigen Erkenntnis entgegentritt, sondern es gestaltet sich, wird bildhaft. Es wird aus dem abstrakten Begreifen ein Künstlerisches, und man steht zuletzt mit einem Anschauen des Materiell-Wesentlichen da. Also man kann Materialist oder Spiritualist sein - man kommt auf beiden Wegen zu demselben, wenn man nur bis ans Ende geht. Das Schädliche des Spiritualismus besteht auch nicht darinnen, daß man das Spirituelle anfaßt, sondern darinnen, daß man leicht blödsinnig wird, zum nebulosen Mystiker wird, Verwirrungen stiftet, alles nur nebulos anschaut, und es nicht zum konkreten Gestalten bringt.

Es ist nun doch sehr wichtig, daß Sie zu alldem, was wir schon betrachtet haben über die Erkundung des Wesens des Kindes, auch das noch hinzufügen, daß Sie gewissermaßen anschauen am Kinde, ob die kosmische Organisation überwiegend ist, was durch eine plastische Durchgestaltung des Hauptes zum Vorschein kommt, oder ob die irdische Organisation besonders hervorragend ist, was durch ein plastisches Durchbilden des übrigen Menschen, namentlich des Gliedmaßenmenschen, zur Anschauung kommt. Und nun handelt es sich darum, daß wir dann beide Arten von Kindern, die kosmischen Kinder und die irdischen Kinder in der richtigen Weise behandeln.

Die irdischen Kinder: wir müssen uns klar darüber sein, daß bei ihnen viel von Vererbungskräften vorliegt, und die Vererbungskräfte den Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus außerordentlich stark durchziehen. Wir werden bemerken, daß, wenn solche Kinder auch nicht in ihrem allgemeinen Temperament melancholisch sind, wir doch leicht, namentlich wenn wir uns mit solchen Kindern von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkt aus beschäftigen, wenn wir sie fragen, wenn wir sonst an sie herantreten, unter der Oberfläche des allgemeinen Temperaments eine Art melancholischen Nebenton finden. Dieser melancholische Nebenton rührt eben von dem Irdischen der Kinder her, von dem Irdischen der Wesenheit.

Ein Kind, bei dem wir dieses bemerken, werden wir gut behandeln, wenn wir versuchen, es sich hineinfinden zu lassen in solches Musikalische, welches vom melancholischen Mollartigen ausgeht und ins Durartige hineingeht, indem man das Melancholisch-Mollartige ins Durmäßige hineinführt oder im einzelnen musikalischen Stück selbst diesen Übergang an das Kind heranbringt. Es ist ein irdisches Kind gerade durch die Verrichtung zu vergeistigen, die den Körper in Anspruch nimmt beim Musikalisch-Eurythmischen. Wenn insbesondere ein allgemein sanguinisches Temperament vorhanden ist mit kleinen melancholischen Zügen, ist auch die Malerei etwas, was dem Kinde sehr leicht helfen kann. In jedem Fall müßten wir auch dann, wenn scheinbar ein solches Kind wenig Begabung zum Musikalisch-Eurythmischen zeigt, größte Sorgfalt verwenden, daß wir die gewiß schon vorhandene Anlage bei einem solchen Kind herausbringen.

Wenn wir ein Kind mit besonders deutlich ausgeprägter Kopforganisation haben, dann ist es wieder wichtig, daß wir die betrachtenden Gegenstände, Geschichte, Geographie, Literaturgeschichte an das Kind heranbringen, wir müssen dann aber insbesondere darauf Rücksicht nehmen, daß wir nicht bei dem bloß Kontemplativen bleiben, sondern — wie ich schon gestern in einem anderen Zusammenhang zeigte übergehen zu einer solchen Darstellung, die Gemütszustände hervorruft, Spannungen, das Neugierigsein, das dann entspannt wird, befriedigt wird und so weiter.

Wir müssen gerade bei diesen Dingen uns wiederum angewöhnen, das Geistige mit dem Körperlichen im Einklang zu sehen. Es ist ja wirklich so, daß diese schöne griechische Vorstellung ganz verlorengegangen ist, die eigentlich das Körperlich-Leibliche mit dem Geistig-Seelischen voll in Einklang gesehen hat. Der Grieche hat eigentlich in dem Wirken des Kunstwerkes auf den Menschen immer etwas gesehen, was er auch leiblich betrachtet hat. Er sprach von der Krankheitskrisis, von der Katharsis, und er sprach so auch von der Wirkung des Kunstwerks, er sprach so auch in der Erziehung. Er verfolgte auch tatsächlich solche Vorgänge, wie wir sie gestern angedeutet haben, und wir müssen uns wiederum zurückfinden zu solchen Vorgängen, zu einem solchen Zusammendenken des Geistig-Seelischen mit dem Leiblich-Physischen.

Es ist wichtig, daß wir deshalb alle unsere temperamentvolle Grundlage zusammennehmen, um mit einem starken persönlichen Anteil den Kindern Geschichte beizubringen. Zur Objektivität hat das Kind noch Zeit genug im späteren Leben, die entwickelt sich schon im späteren Leben. Aber diese Objektivität schon in der Zeit anwenden, wo wir dem Kinde von Brutus und Cäsar zu sprechen haben, da objektiv sein wollen und nicht den Gegensatz, den Unterschied zwischen Brutus und Cäsar gefühlsmäßig gegenständlich machen, das ist ein schlechter Geschichtsunterricht. Man muß durchaus drinnenstehen, man muß nicht wild werden und toben, aber man muß einen leisen Anklang von Sympathie und Antipathie gegenüber dem Brutus und Cäsar offen darlegen, indem man die Sache darstellt. Und das Kind muß angeregt werden mitzufühlen, was man ihm selber vorführt. Man muß mit wirklicher Empfindung vor allen Dingen die Geschichte, Geographie, Geologie und so weiter vortragen. Das letztere ist insbesonders interessant, wenn man Geologie vorträgt und tiefstes Mitgefühl für das unter der Erde befindliche Gestein hat. In dieser Beziehung könnte man jedem Pädagogen raten, Goethes Abhandlung über den Granit ja recht mitfühlend einmal durchzunehmen, um zu sehen, wie eine nicht bloß mit dem Vorstellungsleben, sondern mit dem ganzen Menschen in die Natur sich hineinversetzende Persönlichkeit mit dem Urvater, dem uraltheiligen Granit, in ein menschliches Verhältnis kommt. Dann muß das natürlich auf anderes ausgedehnt werden.

Entwickeln wir es in uns selber, dann kommen wir schon dazu, das Kind mit teilnehmen zu lassen an diesen Dingen. Allerdings ist natürlich die Sache vielfach schwieriger, wir müssen uns abstrapazieren bei diesen Dingen; aber auf der anderen Seite wird nur dadurch wirkliches Leben in das Unterrichten und in das Erziehen hineingebracht. Und im Grunde genommen ist alles, was wir auf dem Umweg durch das Gefühl dem Kinde mitteilen, doch dasjenige, was seinem Innenleben Wachstum verleiht, währenddem dasjenige, was wir in bloßen Vorstellungen beibringen, tot ist, tot bleibt. Wir können ja durch Vorstellungen nichts als Spiegelbilder beibringen; wir arbeiten, indem wir ihm Vorstellungen beibringen, mit dem wertlosen Kopf des Menschen, der nur einen Wert hat in bezug auf die Vorzeit, in der er in der geistigen Welt war. Dasjenige, was im Blute liegt, was hier auf der Erde seine Bedeutung hat, das treffen wir, indem wir mit vollem Gefühl die Vorstellungen dem Kinde beibringen.

Es ist schon notwendig, daß wir in uns ein Gefühl ausbilden für so etwas wie diese feindliche, vernichtende Kraft des Raumes unter dem Rezipienten einer Luftpumpe, und je anschaulicher man dem Kinde erzählen kann, nachdem man die Luft ausgepumpt hat, von dem schrecklichen luftleeren Raum unter dem Rezipienten einer Luftpumpe, desto mehr erreichen wir dadurch. In der früheren Sprache waren alle diese Dinge enthalten: Horror vacui, es wurde empfunden das Horrorartige, das ausströmt von einem luftleeren Raum. Das lag in der Sprache drinnen, aber man muß es wiederum fühlen lernen. Man muß fühlen lernen, welche Verwandtschaft besteht zwischen einem luftleeren Raum und einem ganz hageren und ausgedörrten Menschen. Schon Shakespeare läßt ahnen, daß man die — unter Umständen aus gewissen leiblichen Umständen heraus — Dicken, Beleibten liebt, nicht die Dünnen, Dürren mit den kahlen Glatzen, unter denen so viel Vorstellungsmäßiges ist. Also wir müssen diese Verwandtschaft empfinden zwischen den dürren Menschen oder auch der Spinne und dem luftleeren Raum, dann werden wir wie durch Imponderabilien eben dieses Weltgefühl, das unbedingt im Menschen sein muß, in das Kind hinüberleiten.

Man muß immer wiederum, wenn von Pädagogik gesprochen wird, von diesem Verbinden des Vollmenschen mit der Objektivität sprechen, denn nur dadurch kann auch in jenen Teil des Unterrichts eine gewisse Gesundheit hineingebracht werden, der in der materialistischen Zeit eigentlich ganz beträchtlich gelitten hat. Sehen Sie, man ist ja nicht einmal in der Lage, so unverschämt zu werden wie Abderhalden, der nach einer Einleitung zu einer Eurythmieaufführung in Dornach sagte - ich sprach damals auch vom Turnen, von seiner hygienischen Bedeutung und so weiter -, er, als Physiologe, sehe im Turnen nicht etwas, was physiologisch gestützt ist, er sehe im Turnen überhaupt kein Erziehungsmittel, sondern das Schädlichste, was man sich vorstellen könne. Er wollte es nicht als Erziehungsmittel gelten lassen, es sei kein Erziehungsmittel, sondern eine Barbarei. Mit der heutigen Welt kann man nicht so unverschämt sein, sonst würden einen die Leute sehr stark angreifen in der Weise, wie es heute geschieht. Wenn man diese Sache bedenkt, nicht wahr, wie ein Götze, wie ein Fetisch wirkt alles Turnmäßige, das heißt dasjenige, was bloß ins LeiblichPhysische im schlechtesten Sinne der heutigen materialistischen Wissenschaft getragen wird, sei es das stark Physische, das Überphysische oder Unterphysische des schwedischen Turnens oder das Physische des deutschen Turnens. Diese Dinge gehen darauf aus, den Menschen als ein Wesen anzusehen, das nur leiblich-physisch ist, aber nach der schlechten Vorstellung, die das materialistische Zeitalter heute herausgebildet hat, nicht nach der Vorstellung, die ich vorhin gemeint habe. Man geht davon aus: eine solche Haltung soll der Mensch haben; man beschreibt diese Haltung. Man sagt also: der Rücken darf nicht so stark ausgehöhlt werden, nur bis zu einem gewissen Grad; die Brust muß in einer bestimmten Weise geformt sein, Arme und Hände müssen in einer gewissen Weise bewegt werden, die gesamte Haltung des Körpers -, kurz, man denkt nicht an den Menschen als solchen, sondern an das Bild, das man sich gemacht hat. Das kann man aufzeichnen, man kann es aus Papiermaché formen. Da ist alles drinnen in der Plastik aus Papiermaché, was im schwedischen Turnen von der richtigen Haltung gesagt werden kann. Dann kann man den Menschen dazu benützen so wie einen Sack und kann ihn das nachmachen lassen. Man hat, wenn man diese Prozedur ausführt, mit dem wirklichen Menschlichen gar nichts zu tun, man hat es mit einer Figur aus Papiermaché zu tun, in der alles, was das schwedische oder das deutsche Turnen vorschreibt, enthalten ist. Dann läßt man den Menschen, ohne sich darum zu bekümmern, was er weiter ist, sich so halten, solche Übungen zu machen und so weiter. Nur hat eigentlich niemand Rücksicht genommen, daß man einen Menschen vor sich hat.

Die Sache ist eben dadurch so verwerflich - sie ist verrucht im Grunde genommen -, trotzdem es ein tiefer Einschlag in unsere sogenannte Zivilisation ist, weil dadurch der Mensch auch praktisch ausgeschaltet wird, nicht nur theoretisch durch die Wissenschaft, sondern praktisch wird der Mensch ausgeschaltet durch dieses Turnen. Er wird zum Imitator einer Papiermachéfigur gemacht. Und darum sollte es sich beim Erziehen nie handeln, sondern darum, daß der Mensch, indem er turnt, diejenige Haltung annimmt, diejenigen Bewegungen macht, die er auch erlebt, innerlich erlebt. Und er erlebt sie. Nehmen wir die Atmungsfunktionen. Wir müssen wissen, daß Kinder dazu zu bringen sind, im Einatmen etwas zu haben wie, ich möchte sagen, ein leises Anklingen an eine gut schmeckende Speise, die durch den Gaumen hinuntergeht. Aber es soll nicht bis zum wirklichen Geschmacksvorstellen, Geschmackswahrnehmen kommen, sondern es soll so ein Anklingen im Einatmen sein, man soll etwas von der Frische der Welt beim Atmen erleben können. Man soll die Kinder einatmen lassen und sie etwas empfinden lassen von der Frische der Welt. Man soll versuchen, sie sagen zu lassen: Wie ist denn eigentlich das gefärbt, was du da einatmest? — und man wird darauf kommen, daß das Kind in dem Moment, wo es tatsächlich den Atem richtig empfindet, so etwas findet wie: Es ist grünlich, so natürlich grün. — Da hat man etwas erreicht, wenn man das Kind dazu gebracht hat, das Einatmen grünlich zu finden. Dann wird man immer bemerken: das Kind verlangt jetzt eine. gewisse Körperhaltung für das Einatmen, es bildet durch inneres Erleben die richtige Körperhaltung für das Einatmen heraus. Dann kann man die Übung machen lassen. Ebenso muß man das Kind dazu bringen, beim Ausatmen eine entsprechende Empfindung zu erleben. In dem Augenblick, wo es beim Ausatmen einem sagt: Da drin bin ich eigentlich doch ein tüchtiger Kerl -, wenn es das Ausatmen so empfindet, als ob es sich wie ein tüchtiger Kerl vorkäme, als ob es seine Kräfte empfände, seine Kräfte im Ausatmen der Welt mitteilen wollte: wenn es diese Empfindung hat, dann erlebt es auch in der richtigen Weise als etwas durchaus ihm Angemessenes die entsprechende Bewegung des Unterleibs, der sonstigen Gliedmaßen, die Haltung des Kopfes, der Arme. Wenn es nur einmal das volle Gefühl des Ausatmens hat, dann erlebt das Kind die richtige Bewegung.

Da haben wir den Menschen drinnen, da haben wir den Menschen wirklich vor uns, da lassen wir ihn nicht wie einen Mehlsack dasjenige nachmachen, was eine Papiermachéfigur macht. Da bewegen wir mit dem Seelischen zusammen, das sein Körperlich-Physisches nach sich zieht. Wir holen die Körperbewegung aus dem Kinde heraus nach dem geistig-seelischen Erlebnis. Ebenso wie dieses, sollten wir auch in anderem, was das Kind fühlen kann, ich will sagen, an irgendwelchen Bewegungen der Arme, der Beine, im Laufen und so weiter, in der bloßen Haltung - überall sollten wir dieses seelische Erleben entwikkeln, das sein Körperlich-Physisches von selber fordert. Und dann, dann ist eigentlich das Turnen in unmittelbaren Anschluß an die Eurythmie gebracht, und das soll es auch sein. Die Eurythmie bringt unmittelbar ein Geistig-Seelisches zum Vorschein, durchseelt und durchgeistigt das ganze Bewegliche des Menschen. Sie nimmt dasjenige zum Ausgangspunkt, was sich der Mensch geistig-seelisch im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung erarbeitet. Aber auch das Physisch-Körperliche kann geistig erlebt werden. Man kann das Atmen, den Stoffwechsel erleben, wenn man es weit genug bringt nach dieser Richtung. Da kann der Mensch sich selber weit genug bringen, da kann der Mensch sich selbst empfinden, sein Körperlich-Leibliches mitempfinden. Und dann kann, ich möchte sagen, dasjenige, was auf dem höheren Gebiet als Eurythmie an das Kind herantritt, auslaufen in das Turnen. Man kann durchaus die Brücke schlagen zwischen Eurythmie und Turnen. Aber dieses Turnen soll nicht anders gemacht werden, als indem man dasjenige, was das Kind ausführt im Turnen, aus dem Erleben des Körperlich-Physischen herausholt, aus dem Erleben, aus dem geistig-seelischen Erleben herausholt und das Kind das KörperlichPhysische dem anpassen läßt, was es erlebt.

Es ist natürlich notwendig, daß wir, indem wir so unterrichten, viel lernen; denn man muß sich mit solchen Vorstellungen viel beschäftigen, wenn man sie für sich selbst und namentlich im Unterricht anwenden will. Sie prägen sich schlecht ins Gedächtnis ein. Es ist fast so mit diesen Dingen, wie es manchen Mathematikern geht mit den mathematischen Formeln; sie können sich keine Formeln merken, aber sie können sie im Augenblick wieder bilden. Und so geht es uns mit diesen Vorstellungen, die wir uns über den lebendigen leiblich-geistigs-eelischen Menschen bilden: wir müssen sie uns immer ganz lebendig präsent machen. Aber das kommt uns gerade wieder zugute. Dadurch, daß wir aus dem Vollmenschen heraus wirken, dadurch wirken wir anregend auf die Kinder. Sie werden immer bemerken, wenn Sie selbst viel zu tun hatten, um eine Unterrichtsstunde vorzubereiten, viel gerungen haben mit dem Unterrichtsstoff, und dann in die Klasse gehen, dann lernen die Kinder viel anders, als wenn Sie der hocherhabene Herr Lehrer sind, der sich ganz behaglich vorbereitet. Ich habe auch solche kennengelernt, die auf dem Wege zur Schule ganz behaglich gingen und sich schnell die Dinge durchlasen, die sie vorbringen sollten. Das hat schon einen tiefen Bezug auf das Unterrichten, wenn man selber unmittelbar ringt, nicht nur bei den Dingen ringt, die zu den mitzuteilenden gehören, sondern auch bei anderen Dingen, die zu den Geschicklichkeiten gehören. Auch mit diesen soll man ringen.

Es gibt im Leben geistige Bezüge. Hat man geistig vorher selbst ein Lied, das man das Kind singen läßt, zuerst gehört, dann wirkt es mehr, indem das Kind es ausbildet, als wenn man es vorher nicht im Geiste gehört hat. Diese Dinge haben einen Bezug. Es gibt in der physischen Welt ein Wirken der geistigen Welt. Man muß dieses Wirken der geistigen Welt anwenden besonders in der Pädagogik und in der Didaktik und zum Beispiel beim religiösen Unterricht. Wenn man, indem man ihn vorbereitet, eine natürliche fromme Stimmung empfindet, dann wirkt dieser religiöse Unterricht auch auf das Kind. Wenn man diese fromme Stimmung nicht entwickelt, dann wird nicht viel werden aus dem Religionsunterricht in bezug auf das Kind.

Second Lecture

In my introductory remarks yesterday, I wanted to make it clear how important it is to approach teaching with a fundamental understanding of human beings, or rather of humanity, and, in a sense, of the school system as a unified organism. Today, I would like to present a few principles that we can then build on.

If we really want to understand the nature of human beings in the right way, it is so important to say goodbye to many of the prejudices that the modern scientific worldview has brought with it. If you hear anyone today talking about human beings and what they do logically, what they develop as logic, you will hear the view that human beings, even if they are not materialists, think with a spiritual organism, that they perform logical functions with the spiritual organism, and that they need their brain as a kind of mechanism to perform these logical functions. People think that all thinking functions, all logical activities, are tied to the brain. They then try to distinguish between the logical activities in mental image, judging, reasoning, and drawing conclusions. Isn't it true that even in school we have to practice imagining, judging, reasoning, and drawing conclusions with children?

Now, this view that everything logical is, in a sense, a function of the head has become so established that people have gradually lost their unbiased view of the reality of this area. And when one speaks of this reality, people will say: Prove it to me. But the proof really lies in unbiased observation, in noticing how this logic unfolds in human beings. Of the logical functions: mental image, judging, and reasoning, only the mental image is actually a real function of the head. And we should be very aware that only the formation of mental images, but not judging and reasoning, is a function of the head.

You will say: Gradually, the head is being rendered completely useless by Spiritual Science. — But this is actually something that corresponds to the deepest sense of reality, for we humans do not actually have so much in our heads in the life between birth and death. Outwardly, in its form, in its physical form, the head is indeed the most perfect thing we have. But this is because it is actually a reflection of our spiritual organization between death and a new birth. In a certain sense, it is a seal impression of what we were before our birth, before our conception. Everything that is spiritual and soul-related has been imprinted in our head, so that it represents a mental image of our pre-birth life. And actually, only the etheric body is fully active in our head, apart from the physical body. The other members of the human being, the astral body and the I, fill the head, but they reflect their activity in it; they are active in themselves and the head only reflects their activity. This head is, in general, present from the outside as an image of the supersensible world. I pointed this out in last year's course when I drew your attention to the fact that we actually carry the head as a special entity on our human organism. We can regard the rest of the human organism as a kind of carriage and the head as the one who rides in this carriage, or we could also regard it, if we regard the rest of the organism as a horse, as a rider on this horse. It is actually separate from this connection with the rest of the earthly outside world. It sits on the body like a parasite and also behaves like a parasite. It is necessary to abandon the materialistic view that we have so much from the head — we need it as a mirroring apparatus. That is necessary. We must learn to regard the head as an image of our prenatal mental and spiritual organization.

But mental image is actually tied to the head, not judgment. Judgment is actually tied to the middle organism, namely the arms and hands. We actually judge with our arms and hands. We imagine with our head. So when we imagine the content of a judgment, the judging itself takes place in the mechanism of the arms and hands, and only the mental image of the imagination takes place in the head. You will be able to understand this inwardly and then see it as an important didactic truth. You can say to yourself: the middle organism is actually there to convey the world of feelings. The rhythmic organism of the human being is essentially the seat of the emotional world; it is actually there to convey the emotional world. Judgment has a deep affinity with feeling. Even the most abstract judgment has an affinity with feeling. When we make a judgment: Karlchen is well-behaved — that is a judgment, then we have the feeling of affirmation; and the feeling of affirmation and negation plays a major role in judgment, indeed the feeling that is expressed in the predicate in relation to the subject. And it is only because feeling belongs so strongly to the semi-conscious that we do not pay attention to how much feeling is involved in judging. Now, because human beings are supposed to be primarily judging beings, their arm organism is brought into harmony with the rhythmic organism, but at the same time freed from the ongoing rhythmic organism. Thus, in the physical connection between the rhythmic organism and the freed arm organism, we have also expressed physically and sensually the way in which feeling is connected with judgment.

Closing, forming conclusions, is now connected with the legs and feet. Of course, you will be laughed at today if you tell a psychologist that you do not close with your head, but with your legs, with your feet, but the latter is the truth, and if we as human beings were not organized on legs and feet, we would not be able to form conclusions. The thing is this: we form a mental image with the etheric body, which is supported by the head organization, but we judge — in a primal, elementary way — with the astral body, which is supported by the arms and hands for judging. We conclude with the legs and feet, because we conclude with the ego, which is supported by the legs and feet.

You can see from this that the whole human being is involved in logic. And it is very important to understand this, to think of the whole human being as involved in logic. Modern knowledge knows very little about human beings because it does not know that the whole human being is involved in logic; it believes that human beings only use their heads. Now, insofar as they are beings with legs and feet, human beings are involved in the earthly world in a completely different way than beings who are only involved with their heads. You can visualize this with the following little picture (see drawing). If you have a schematic mental image of the human being, we can form the following concept: Let us assume that this person is lifting some weight (A) with this hand, say a kilogram. He lifts it with his hand. Let us now disregard the fact that this person is lifting the one-kilogram weight with his hand, but instead let us attach a rope here (s), a pulley here (R), and let the rope pass over the pulley, and hang another one-kilogram weight here (B), or perhaps a slightly heavier weight. If we have a weight that is slightly heavier than the kilogram weight, this device pulls the other one up. We have placed a mechanical device in the world that does exactly the same thing as when I use my arm to lift the weight. Isn't it true that when I lift the weight with my arm by any amount, it is exactly the same action as when I attach the heavier weight and let the other one pull it up? I exert my will, and in doing so I do something that can be accomplished in the same way as with purely mechanical devices. What can be seen here with this kilogram weight, this pulling up, is a completely objective event. When my will intervenes, the external image does not change. I then stand with my will completely within the objective world. I switch myself into the objective world. I no longer distinguish myself from the objective world by exercising my will.

What I am doing here becomes particularly clear when I walk or do anything with my legs. When I walk and do something with my legs, what the will accomplishes is a completely objective process; it is something that happens in the world. In the unfolding of the will, it is basically irrelevant to the appearance of the external event whether only a mechanical process is taking place or whether my will is intervening. My will only directs the course of mechanical processes. This is most evident when I perform functions that involve my legs and feet. Then I am basically outside myself, I flow together with the objective world, I am completely part of the objective world.

I cannot say the same about my head. The functions of the head tear me out of the world; I cannot place what I call seeing and hearing, which ultimately leads to a mental image, into the world in this objective way. My head does not belong in the world at all. It is a foreign product in this earthly world, it is the afterimage of what I was before I descended to earth. The extreme ends are the head and the legs, and in the middle stands — because the will is already at work there, but works specifically with the feeling — between them stands the organization of the arms and hands. Please think about how human beings are actually separated through their heads, how they carry their heads in from a spiritual world, how the head is actually the physical witness to the fact that human beings belong to a spiritual world, and how human beings force themselves into the physical world by adapting their feeling and will organs to all the external institutions and laws. No sharp boundaries can be drawn between external events and my volitional activity. However, a sharp boundary must always be drawn between external events and what is conveyed through the head in the form of mental images.

Here, I would say, you can draw the line in order to understand human beings even better. Human beings are transported into embryonic life by first developing the organization of the head. It is nonsense to think that the organization of the head is only a matter of heredity. The head organization is — it is also spherical — a replica of the cosmos, and the forces of the cosmos work into it. What human beings receive through the stream of heredity passes through the organization of their arms and legs. It is only through these that they are actually children of their parents. Through these, he is connected to earthly forces, for the head is not at all accessible to earthly forces, not even to fertilization. The head is organized from the cosmos. And if the head shows similarities to the parents, this is because it develops from the rest of the organism, is nourished by its blood, and is influenced by the rest of the organism. But what the head is in its formation is a result of the cosmos. And a result of the cosmos is, above all, that which has to do with the nerve-sense organism, insofar as it is connected to the head. For we also bring the nerve-sense organism in from the cosmos and then allow it to grow into the rest of the organism.

It is very important to consider such things, because in doing so we learn to eliminate the nonsense within ourselves, as if we were becoming particularly intellectual or spiritual by not talking about the physical body at all and only ever talking about something abstractly intellectual or spiritual. On the contrary, one becomes truly intellectual, truly spiritual, when one is able to see through the relationship between the physical and the spiritual in the right way, when one is able to see through that: in relation to the head, you are organized from the cosmos; in relation to the leg organism, you are a child of your parents and ancestors. And these insights then very strongly influence our feelings, because they are insights into realities, whereas the insights conveyed by today's abstractions — regardless of whether one means these abstractions or the description of the material — basically have nothing to do with reality. Therefore, they cannot stimulate us emotionally. That which enters into reality in this way also stimulates us emotionally, and therefore you should familiarize yourself thoroughly with a thought and try to develop it deeply in an educational way. That thought is this: it does not really matter whether you view human beings in terms of their physical body, if you view them correctly, or in terms of their spiritual and soul aspects. When you learn to view the spiritual-soul in the right way, you come to know it as something creative that allows the physical-bodily to flow out of itself. You can see this in creation, the spiritual-soul aspect. And if you view this artistically in the right way, you gradually lose all materiality, and it becomes spiritual all by itself. The physical-bodily aspect is transformed into a spiritual aspect through a correct mental image.

If you stand on the ground of spiritual science, of anthroposophy, it does not matter whether you are a materialist or a spiritualist. It does not matter at all. The harmfulness of materialism does not lie in getting to know material phenomena and entities; for if you get to know them thoroughly, you lose your silly materialistic concepts, and the whole thing is transformed into something spiritual. The harmfulness lies in the fact that one easily becomes feeble-minded if one focuses on the material and does not think things through to their conclusion and does not go beyond what one sees with the senses. Then one has no reality. One does not think the material through to its conclusion; for if one thinks it through to its conclusion, it becomes spiritual in one's mental image. And when one considers the spiritual-soul aspect, it does not remain, when one enters into its reality, that abstract thing that so easily confronts us in today's knowledge, but it takes shape, becomes pictorial. The abstract understanding becomes something artistic, and one is ultimately left with a view of the material essence. So you can be a materialist or a spiritualist – you arrive at the same thing either way, if you only go to the end. The harmfulness of spiritualism does not lie in touching the spiritual, but in easily becoming foolish, becoming a nebulous mystic, causing confusion, seeing everything only nebulously, and not bringing it to concrete form.

It is now very important that you add to everything we have already considered about exploring the nature of the child you also add that you observe in the child, as it were, whether the cosmic organization is predominant, which is revealed by a plastic formation of the head, or whether the earthly organization is particularly prominent, which is revealed by a plastic formation of the rest of the human being, namely the limbs. And now it is a matter of treating both types of children, the cosmic children and the earthly children, in the right way.

Earthly children: we must be clear that they have a great deal of hereditary forces, and that these hereditary forces permeate the limb-metabolic organism extremely strongly. We will notice that even if such children are not melancholic in their general temperament, we will nevertheless easily find a kind of melancholic undertone beneath the surface of their general temperament, especially when we deal with such children from a certain point of view, when we ask them questions, or when we approach them in other ways. This melancholic undertone stems precisely from the earthly nature of children, from the earthly nature of the being.

We will treat a child in whom we notice this well if we try to let them find their way into music that starts from the melancholic minor and moves into the major, by introducing the melancholic minor into the major or by bringing this transition to the child in the individual piece of music itself. It is precisely through the activity that engages the body in musical eurythmy that an earthly child can be spiritualized. If, in particular, a generally sanguine temperament is present with slight melancholic traits, painting is also something that can help the child very easily. In any case, even if such a child appears to show little talent for musical eurythmy, we must take the greatest care to bring out the aptitude that is certainly already present in such a child.

If we have a child with a particularly well-developed head, then it is again important that we introduce the child to the subjects of history, geography, and literary history, but we must take particular care not to remain merely contemplative, but — as I showed yesterday in another context — to move on to a presentation that evokes states of mind, tensions, curiosity, which is then relaxed, satisfied, and so on.

In these matters in particular, we must once again accustom ourselves to seeing the spiritual in harmony with the physical. It is indeed true that this beautiful Greek mental image, which saw the physical and bodily in complete harmony with the spiritual and soulful, has been completely lost. The Greeks always saw something in the effect of a work of art on people that they also considered physical. They spoke of the crisis of illness, of catharsis, and they also spoke of the effect of works of art in this way, and they also spoke of it in education. They actually pursued such processes, as we indicated yesterday, and we must find our way back to such processes, to such a combination of the spiritual and the physical.

It is important that we therefore bring together all our temperamental foundations in order to teach children history with a strong personal involvement. The child will have enough time for objectivity later in life; that develops later on. But to apply this objectivity at a time when we have to talk to the child about Brutus and Caesar, to want to be objective and not to make the contrast, the difference between Brutus and Caesar, emotionally concrete, is bad history teaching. One must definitely be involved, one must not become wild and rave, but one must openly express a quiet sense of sympathy and antipathy towards Brutus and Caesar by presenting the matter. And the child must be encouraged to empathize with what is being presented to them. Above all, one must present history, geography, geology, and so on with genuine feeling. The latter is particularly interesting when one presents geology and has the deepest sympathy for the rock beneath the earth. In this regard, one could advise every educator to read Goethe's treatise on granite with great empathy in order to see how a personality that immerses itself in nature not only with its imagination but with its whole being enters into a human relationship with the primal father, the ancient sacred granite. Then, of course, this must be extended to other things.

If we develop this within ourselves, we will naturally come to involve the child in these things. Of course, this is often much more difficult, and we have to make an effort to do so; but on the other hand, this is the only way to bring real life into teaching and education. And basically, everything we communicate to the child indirectly through feeling is what gives its inner life growth, while what we teach in mere mental images is dead and remains dead. We can teach nothing but mental images through mental images; when we teach mental images, we are working with the worthless head of the human being, which has value only in relation to the past, when it was in the spiritual world. We reach what lies in the blood, what has meaning here on earth, by teaching mental images to the child with full feeling.

It is necessary that we develop a feeling for something like this hostile, destructive force of space under the receiver of an air pump, and the more vividly we can tell the child, after pumping out the air, about the terrible airless space under the receiver of an air pump, the more we will achieve. In the language of the past, all these things were contained: horror vacui, the horror that emanates from a vacuum. It was there in the language, but we have to learn to feel it again. One must learn to feel the relationship between a vacuum and a very gaunt and emaciated person. Shakespeare already hints that — under certain physical circumstances — one loves the fat and corpulent, not the thin and gaunt with their bald heads, which are so full of imagination. So we must feel this connection between the gaunt person or even the spider and the vacuum, then we will, as if by imponderables, convey to the child this very sense of the world that must necessarily be in human beings.