Soul Economy

Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education

GA 303

28 December 1921, Stuttgart

VI. Health and Illness II

It was not my intention in yesterday’s lecture to single out certain types of illnesses nor to specify differing degrees of health, nor is it my aim to do so today as we continue this subject. I merely wish to point out how important it is for teachers to learn to recognize both healing and harmful influences in the lives of their students. True educators, above all else, must have acquired real understanding of the entire human organization. They must not allow abstract educational theories or methods to cause them deviate from their natural or (as we could also call it) natural, intuitive understanding. Abstract theories will only hamper teachers in their efforts. They must be able to look at the children without preconceived ideas.

There is a saying often heard in Central Europe (perhaps this is also known in the West): “There is only one health, but there are numerous illnesses.” Many people believe in this saying, but it really does not stand up to scrutiny. Human beings are so individualized that we all, including children, have our own specific states of health, representing individual variations of the general notion of health. One might just as well coin the saying, “There are as many kinds of health and illness as there are people in the world.” This alone indicates how we must always consider the individual nature of each person. But this is possible only when we have learned to see human beings in their wholeness.

In every human being, soul and spiritual forces continually interact with physical forces, just as hydrogen and oxygen interact in water. We cannot see hydrogen and oxygen as separate elements in water, and similarly we cannot ordinarily see the human soul and spirit as separate from the physical and material aspects of a human being when we look at someone. To recognize the true relationship between the soul and spiritual aspect and the physical nature of a human being, one must first get to know them intimately, but we cannot do this through just our ordinary means of knowledge. Today we are used to seeing the human being from two points of view. One involves the study of physiology and anatomy, in which our image is not based on the living human being at all, but upon the human corpse, with the human soul and spirit excluded. The other point of view comes from psychology, the study of our inner life. But psychologists can form only abstractions, thin and cold concepts for our naturalistic and intellectualistic era. Such researchers warm up only when they try to plumb the depths of human emotions and will impulses. In their true essence, however, these are also beyond their grasp; in a vague way, they see only waves surging up from within.

It is obvious that cold, thin, and pale concepts of the human psyche will not give us a true sense of reality. What I am about to say might seem strange from the modern point of view, but it is true nevertheless. People today adopt a materialistic attitude, because for them spirit has become too attenuated and distant; as a result, when people observe the human inner life, it no longer has any sense of reality. The very individuals who live with the most abstract thoughts have become the most materialistic people during our cultural epoch. Contemporary thinking—and thinking is a spiritual activity—turns people into materialists. On the other hand, those who are relatively untouched by today’s scientific thinking, people whose minds turn more toward outer material events, are the ones who sense some of the mystery behind external processes. Scientific thinking today leaves little room for life’s mysteries. Its thoughts are thin and transparent and, for the most part, terribly precise; consequently, they are not grounded in the realities of life. The material processes of nature, on the other hand, are full of mysteries. They need more than the clarity of intellectual thoughts, since they can evoke a sense of wonder, in which our feelings also become engaged.

Those who have not been influenced by today’s sterile thinking and have remained aloof from the rigorous discipline of a scientific training are more open to the mysteries of the material processes of nature. But here there is a certain danger; in their longing to find spirit in nature, they look for the spiritual as if it, too, were only matter. They become spiritualists. Modern scientific thinking, on the other hand, will not produce people who are directed to the spiritual, but people who are materialists. A natural openness toward the material world, however, easily produces a spiritualistic approach, and here lies a strange contradiction typical of our time. But neither the materialistic view nor the spiritualistic view can provide a true picture of the human being. This is accomplished only by discriminating how—in every organ of the human being—the soul and spiritual element interacts with the material nature of the human being.

People do talk about soul and spirit today, and they talk about our physical aspect. They then philosophize about the relationship between these two aspects. Experts have presented detailed theories, which may be ingenious but never touch reality, merely because we find reality only when we perceive the complete interpenetration of the soul and spiritual element and the physical, material element of the whole human being. If we look at the results of today’s investigations, both in physiology and in psychology, we always find them vague and colorless.

Today, when people look at another person, they have the feeling they are confronted by a unified whole, because the other person is neatly wrapped up in skin. One generally fails to realize that this seeming singularity is the result of the cooperation of the most diverse organs. And if we say that this unity must not be assumed, opponents quickly arise and accuse us of destroying the idea that the human being is unified, which they consider fundamental. However, their concept of human oneness is still just an abstract thought unless they can harmonize the manifold members of the human being into a single organization.

When people look inward, they sum up all that lives within them with the little word I. Eminent people such as John Stuart Mill worked hard to formulate theories about the nature of this inner feeling of identity, which we express with the word I. Just stop and think, however, how vague this idea of a point-like I really is. You will soon see that you no longer grasp concrete reality with this concept. In German, only three letters form this little word (ich), and in English even fewer. People seldom manage to get beyond the outer meaning of these letters, and consequently today’s knowledge of the human being remains vague, regardless of whether you look at the inner life or the physical constituents.

It is the ability to see the spiritual and physical working together that enriches our efforts at comprehending the nature of the human being. There are many today who are inwardly satisfied by Goethe’s words, “Matter in spirit, spirit in matter.” It is good if these words make people happy, since they certainly express a truth. But for anyone who has the habit of seeing spirit and matter working together everywhere, these words express a mere triviality; they extol the obvious. The fact that so many receive this somewhat theoretical dictum with such acclaim just goes to show that they no longer experience its underlying reality. Theoretical explanations usually hide the loss of concrete inner experience. We find an example of this in history when we look at theories about the holy communion, theories that were widely discussed beginning at the very point in time when people had lost their ability to experience its reality. In general, theories are formed to explain what is no longer experienced in practice.

The attitude of mind expressed so far will be helpful to those who wish to practice education as an art. It will enable you to acquire a concrete image of the manifold members of the human being instead of having to work with some vague notion of human oneness. An image of the human being as an organic whole will emerge, but in it you can see how the various members work together in harmony. Such a picture inevitably leads to what I have indicated in my book Riddles of the Soul: the discovery of the three fundamental human aspects, each different from the others in both functions and character. Externally, the head as an organization appears very different from, say, the organism of the limbs and metabolic system. I link these two latter systems together, because the metabolism shows its real nature in the activity of a person’s limbs. In morphological terms, we can see the digestive system as a kind of continuation (though perhaps only inwardly) of a person in movement. There is an intimate relationship between the limbs and the digestive systems. For instance, the metabolism is more lively when the limbs are active. This relationship could be demonstrated in detail, but I am merely indicating it here. Because of their close affinity, I group these two systems together, although, when each one is seen individually, they also represent certain polarities.

Now let us look at the human shape, beginning with the head. For the moment, we will ignore the hair, which, in any case, grows away from the head and, because it is a dead substance, remains outside the living head organization. Human hair is really a very interesting substance, but further details of this would only lead us away from our main considerations.

The head is encased in the skull, which is formed most powerfully at the periphery, whereas the soft, living parts are enclosed within. Now compare the head with its opposite, the limb system. Here we find tubular bones enclosing marrow, which is typically not considered as important for the entire organism as the brain mass in the skull. On the other hand, here we find the most important parts—the muscles—attached on the outside, and from this point of view we see a polarity characteristic of human nature. This polarity consists of the nerves and senses, centered primarily (though not exclusively) in the head, and the metabolism localized in the metabolic and limb systems.

Despite this polarity, the human being is of course a unity. At this point, however, we must not be tempted to make up diagrams that divide the human being into three parts (as though these parts could exist separately), which we then define as the nervous-sensory system, a second part, which will be discussed shortly, and, finally, the metabolic and limb organization. It is not like this at all. Metabolic as well as muscular activities constantly take place in the head, and yet we can say that the head is the center of the organization of nerves and senses. Conversely, the organization of digestion and limbs are also permeated by forces emanating from the head, but we can nevertheless call it the seat of the “metabolic-limb system.”

Midway between these two regions, we find what we can call the rhythmic system of the human being, located in the chest, where the most fundamental rhythms take place: breathing and blood circulation. Each follows its own speed; the rhythm visible in a person’s breathing is slower, and the blood circulation, felt as the pulse, is faster. This “rhythmic organization” acts as a mediator between the other two poles. It would be tempting to go into further detail, but since we have gathered to study the principles and methods of Waldorf education, I must refrain. However, if you can see the chest organization from the point of view just indicated, you find in every one of its parts—whether in the skeletal formation or in the structure of the inner organs—a transition between the head organization and the metabolic-limb system. This is the image that emerges when we observe human beings according to their inner structure rather than foggy notions about human unity. But there is more, for we are also led to understand the various functions within the human being, and here I would like to give you an example. One could mention countless examples, but this must suffice to show how important it is for real educators to follow the directions indicated here.

Imagine that a person suffers from sudden outbursts of temper. Such eruptions may already occur in childhood, and then a good teacher must find ways of dealing with them. Those who follow the usual methods of physiology and anatomy might also consider the psychological effects in this person. Furthermore they may include the fact that, along with extreme anger, there is an excess of gall secretion. However, these two aspects—the physical and psychological—are not generally seen as two sides of the same phenomenon. The soul-spiritual aspect of anger and the physically overactive secretion of bile are not seen as a unity. In a normal person, bile is of course a necessary for the nutritive process. In one who is angry, this gall activity becomes imbalanced and, if left alone, such a person will finally suffer from jaundice, as you all know.

If we consider both the soul-spiritual and the physical aspects, we see that a tendency toward a certain illness may develop, but this alone is still not enough to assess human nature, because, while bile is being secreted in the metabolism, an accompanying but polar opposite process occurs in the head organization. We are not observing human nature fully unless we realize that while bile is secreted, an opposite process is taking place at the same time in the head organization. In the head, a milk-like sap, produced in other parts of the body, is being absorbed. In an abnormal case, if too much bile is secreted into the metabolism, the head organization will try to fill itself with too much of this fluid; consequently, once the temper has cooled down, one feels as if one’s head were bursting. And whereas an excess of bile will cause this milky sap to flow into the head, once the temper has cooled down this person’s face may turn somewhat blue. If we study not just the external forms of bones and organs but also their organic processes, we certainly can find a polarity between the nervoussensory organization centered in the head and the limb-metabolic system. Between these lives the rhythmic system with its lung and heart activities, which always regulate and mediate between the two outer poles.

If we keep our images flexible and avoid becoming too simplistic by picturing the various organs in a static way—perhaps by making accurate, sharp illustrations—we are certain to be captivated by the multifarious relationships and constant interplay within these three members of the human being. If we look at the rhythmic activity of breathing, we see how during inhalation the thrust is led to the cerebrospinal fluid. While receiving these breathing rhythms, this fluid passes the vibrations right up into the brain fluid, which fills the various cavities of the brain. This “lapping” against the brain, so to speak, caused by rhythmic breathing, stimulates the human being to become active in the nervous-sensory organization. The rhythms caused by the process of breathing are constantly passed on via the vertebral canal into the brain fluid. Thus the stimuli activated by breathing constantly strive toward the region of the head.

If we look downward, we see how rhythmic breathing, in a certain sense, becomes more “pointed” and “excited” in the rhythm of the pulse and how the blood’s circulation affects the metabolism with each exhalation—that is, while the brain and cerebrospinal fluid push downward. If we look with lively, artistically sensitive understanding at the breathing process and blood circulation, we can follow the effects of the pulsing blood upon both the nervous-sensory organization and the metabolic-limb system. We see how, on the one side, the processes of breathing and blood circulation reach up into the brain and the region of the head, and, on the other, in the opposite direction into the metabolic-limb system. If we gradually gain a living picture of the human being in this way, we can make real progress in our research. We can form concepts that accord fully with the nature of the human central system. Such concepts must not be so simple that we can make them into diagrams; schemes and diagrams are always problematic when it comes to understanding the constant, elemental weaving and flowing of human nature.

In the early days of our anthroposophic endeavors, when we were still operating within theosophical groups (permit me to mention this), we were faced again and again with all sorts of diagrams, generously equipped with plenty of data. Everything seemed to fit into elaborate, neat schematic ladders, high enough for anyone to climb to the highest regions of existence. Some members seemed to view such diagrammatic ladders as a kind of spiritual gym equipment, with which they hoped to reach Olympic heights; everything was neatly enclosed in boxes. These things made one’s limbs twitch convulsively. They were hardly bearable for those who knew that, to get hold of our constantly mobile human nature in a suprasensory way, we must keep our ideas flexible and alive. Fixed habits of thinking made us want to flee. What matters is that, in our quest for real knowledge of the human being, we must keep our thinking and ideation flexible, and then we can advance yet another step.

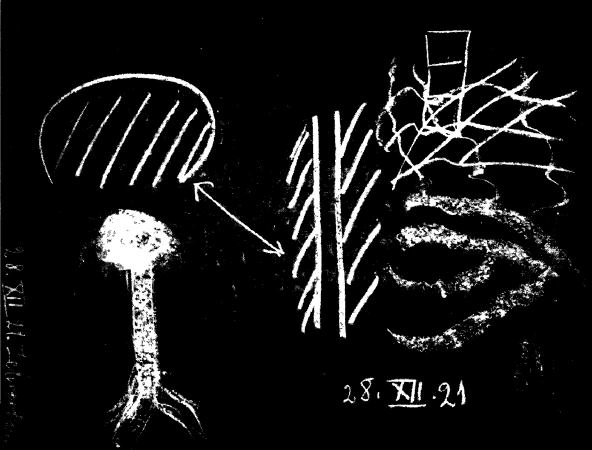

Now, as we try to build mental images of how this rhythm between breathing and blood circulation becomes changed and transformed in the upper regions, we are led to the following idea, which I will sketch on the blackboard—not as a fixed scheme but merely as an indication (see drawing). Let the thick line represent the mental image of some sort of rope, which will help us imagine, roughly, the processes in our breathing and blood circulation. This is one way we can get hold of what exists beyond the physical blood in a much finer and imponderable substance of the “etheric nerves.”

Now, using our imagination, we can go further by looking from the chest organization upward, feeling inwardly compelled, as it were, to “fray” our images and transform them into fine threads that interweave and form a delicate network. Thus we can grasp through mental images—turned upward and modified—something that occurs externally and physically. We find that we simply have to fray these thick cords into threads. Imagining this process, we gradually experience the white, fibrous brain substance under the grey matter. In our mental images we become as flexible as the very processes that pervade human nature.

Directing your image making in the opposite direction, downward, you will find it impossible to split up or fray your mental images into fine threads to be woven into some sort of texture, as seen externally in the nervous system; such threads simply vanish, and you lose all traces of them. Otherwise, you would be led astray into forming images that no longer correspond to external reality. If you follow the brain as it continues downward into the spinal cord through the twelve dorsal vertebrae—through the lumbar and sacral vertebrae and so on—you find that the nerve substance, which now is white on the outside and grey inside, gradually dissolves toward the region of the metabolism. Somehow it becomes impossible to imagine the nerves continuing downward. We cannot get a true and comprehensive picture of the human being unless our images are able to transform; we must keep our images flexible.

If we look upward, our mental pictures change from those we find when looking down. We can recreate in images the flexibility of human nature, and this is the beginning of an artistic activity that eventually leads researchers to what we find externally in the physical human being. So we avoid the schism caused by looking first at the outer physical world and forming abstract concepts about it. Rather, we dive right into human nature. Our concepts become lively and stay in harmony with what actually exists in the human being. There is no other way to understand the true nature of the human being, and this is an essential prerequisite in the art of education.

To know the human being, we have to become inwardly flexible, and then we can correctly discover these three members of the human organization and how they work together to create a healthy equilibrium. We will learn to recognize how a disturbance of this equilibrium leads to all kinds of illnesses and to discriminate, in a living way, between the causes of health and illness in human life. If you look at the creation of the human being with the reverence it deserves, you will not oversimplify this intricate human organization by calling it a natural unity. And, when looking at the chest region, if you imagine coarse, rope-like shapes that become more refined as you approach the region of the head, until they fray into simple threads, you begin to reach the material reality. You find your imagination confirmed outwardly by the physical nerve fibers and by the way they interweave.

This is especially important when we consider the entire span of human life, because these three members of the human organization are interrelated in different ways during the various stages of life. During childhood the soul-spiritual element works into the physical organization in a completely different way than it does during the later stages. It is essential that we pay enough attention to these subtle changes. How94 ever, if we are willing to develop the kind of mental images indicated here, we gradually learn to broaden and deepen previous concepts.

It seem I offended many readers of my book The Spiritual Guidance of the Individual and Humanity when I pointed out that children have a kind of wisdom that adults no longer possess. I certainly do not wish to belittle adult wisdom and abilities, but just imagine what would happen if, at an early stage when the brain and the other organs are still relatively unformed, our whole organization had to come about and form itself by relying solely on our personal wisdom. I am afraid we would turn out rather poorly. Certainly, children form their brains and other organs entirely subconsciously, but there is great wisdom at work nonetheless.

When you consider the whole of human life as described in previous lectures, you can recognize this wisdom, especially if you have a sense for what children’s dreams can tell you. Adults tend to dismiss these dreams as childish nonsense, but if you can experience their underlying reality, children’s dreams, so different from adult dreams, are in fact very interesting. Of course, children cannot express themselves clearly when speaking about their dreams, but there are ways of discovering what they are trying to say. And then we find that, through images of spirit beings in their dreams, children dimly experience the sublime powers of wisdom that help shape the brain and other physical organs. If we approach children’s dreams with a reverence in tune with their experience, we see a pervading cosmic wisdom at work in them. From this point of view (forgive this somewhat offensive statement), children are much wiser, much smarter than adults. And when teachers enter the classroom, they should be fully aware of this abundance of wisdom in the children. Teachers themselves have outgrown it, and what they have gained instead—knowledge of their own experience—cannot compare with it in the least.

Adult dreams have lost that quality; they carry everyday life into their dreams. I have spoken of this from a different perspective. When adults dream, they carry daytime wisdom into their life at night, where it affects them in return. But when children dream, sublime wisdom flows through them. Though unaware of what is happening, children nevertheless retain a dim awareness upon awaking. And, during the day, when they sit in school, they still have an indistinct sense of this cosmic wisdom, which they cannot find it in the teacher. Teachers, on the other hand, feel superior to children in terms of knowledge and wisdom. This is natural, of course, since otherwise they could not teach. Teachers are conscious of their own wisdom, and from this point of view, they certainly are superior. But this kind of wisdom is not as full and sublime as that of the child.

If we put into words what happens when a young child, pervaded by wisdom, meets the teacher, who has lost this primordial wisdom, the following image might emerge. The abstract knowledge that is typical of our times, and with which teachers have been closely linked for so many years of life, tends to make them into somewhat dry and pedantic adults. In some cases, their demeanor and outer appearance reveal these traits. Children, on the other hand, have retained the freshness and sprightliness that spring from spiritual wisdom.

Now, when teachers enter the classroom, children have to control their high spirits. Teachers feel that they are intelligent and that their students are ignorant. But in the subconscious realms of both teachers and students, a very different picture emerges. And if dreams were allowed to speak, the picture again would be quite different. Children, somewhere in their subconscious, feel how stupid the teacher is. And in their subconscious, teachers feel how wise the children are.

All this becomes a part of the classroom atmosphere and belongs to the imponderables that play a very important role in education. Because of this, children cannot help confronting their teachers with a certain arrogance, however slight, of which they remain completely unaware. Its innate attitude toward the teacher is one of amusement; they cannot help feeling this flow of wisdom pervading their own bodies and how little has survived in the teacher. Instinctively, children contrast their own wisdom with that of their teachers, who enter the classroom somewhat stiff and pedantic—the face grown morose from living so long with abstract intellectual concepts, the coat so heavy with the dust of libraries that it defies the clothes brush. Mild amusement is the uppermost feeling of a child at this sorry sight.

This is how the teacher is seen through the eyes of a child, however unaware the child may be. And we cannot help seeing a certain justification in this attitude. After all, such a reaction is a form of self-protection, preserving the child’s state of health. A dream about teachers would hardly be an elevating experience for young students, who can still dream of the powers of wisdom that permeate their whole being.

In a teacher’s subconscious regions, an opposite kind of feeling develops that is also very real, and it, too, belongs to the imponderables of the classroom. In the child, we can speak of dim awareness, but in the teacher, there lurks a subconscious desire. Though teachers will never admit this consciously, an inner yearning arises for the vital forces of wisdom that bless children. If psychoanalysts of the human soul were more aware of spiritual realities than is usually the case, they would quickly discover the important role that children’s fresh, vital growth and other human forces play in a teacher’s subconscious.

These are some of the invisible elements that pervade the classroom. And if you are able to look a little behind the scenes, you will find that children turn away from the teacher because of a certain disenchantment. They dimly sense an unspoken question: In this adult, who is my teacher, what became of all that flows through me? But in teachers, on the other hand, a subconscious longing begins to stir. Like vampires, they want to prey on these young souls. If you look a little closer, in many cases you can see how strongly this vampire-like urge works beneath an otherwise orderly appearance. Here lies the origin of various tendencies toward ill health in young children. One only needs to look with open eyes at the psychological disposition of some teachers to see how such tendencies can result from life in the classroom.

As teachers, we cannot overcome these harmful influences unless we are sustained by a knowledge of the human being that is imbued with love for humankind—knowledge both flexible and alive and in harmony with the human organism as I have described it. Only genuine love of humankind can overcome and balance the various forces in human nature that have become onesided. And such knowledge of the human being enables us to recognize not just the way human nature is expressed differently in various individuals, but also its characteristic changes through childhood, maturity, and old age. The three members of the human being have completely different working relationships during the three main stages of life, and each member must adapt accordingly.

We need to keep this in mind, especially when we make up the schedule. Obviously, we must cater to the whole being of a child—to the head as well as the limbs—and we must allow for the fact that, in each of the three members, processes that spring from the other two continue all the time. For example, metabolic processes are always occurring in the head.

If children have to sit still at their desks to do head work (more on this and classroom desks later), if their activities do not flow into their limbs and metabolism, we create an imbalance in them. We must balance this by letting the head relax—by allowing them to enjoy free movement later during gym lessons. If you are aware of the polar processes in the head and in the limbs and metabolism, you will appreciate the importance of providing the right changes in the schedule.

But if, after a boisterous gym lesson, we take our students back to the classroom to continue the lessons, what do we do then? You must realize that, while a person is engaged in limb activities that stimulate the metabolism, thoughts that were artificially planted in the head during previous years are no longer there. When children jump and run around and are active in the limbs and metabolism, all thoughts previously planted in the head simply fly away. But the forces that manifest only in children’s dreams—the forces of suprasensory wisdom—now enter the head and claiming their place. If, after a movement lesson, we take the children back to the classroom to replace those forces with something else that must appear inferior to their subconscious minds, a mood of resentment will make itself felt in the class. During the previous lesson, sensory and, above all, suprasensory forces have been affecting the children. The students may not appear unwilling externally, but an inner resentment is certainly present. By resuming ordinary lessons right after a movement lesson, we go against the child’s nature and, by doing so, we implant the potential seeds of illness in children. According to a physiologist, this is a fact that has been known for a long time. I have explained this from an anthroposophic perspective to show you how much it is up to teachers to nurture the health of children, provided they have gained the right knowledge of the human being. Naturally, if we approach this in the wrong way, we can, in fact, plant all sorts of illnesses in children, and we must always be fully aware of this.

As you may have noticed by now, I do not glorify ordinary worldly wisdom, which is so highly prized these days. That sort of wisdom hardly suffices for shaping the inner organs of young people for their coming years. If we have not become stiff in our whole being by the time we mature, the knowledge we have impressed into our minds through naturalistic and intellectual concepts—which is thrown back as memory pictures—all that would eventually flow down into the rest of our organism. However absurd this may sound, a person would become ill if what belongs in the head under ordinary conditions were to flow down into limb and metabolic regions. The head forces act like poison when they enter the lower spheres. Brain wisdom, in fact, becomes a kind of poison as soon as it enters the wrong sphere, or at least when it reaches the metabolism. The only way we can live with our brain knowledge—and I use this term concretely and not as a moral judgment—is by preventing this poison from entering our metabolic and limb system, since it would have a devastating effect there.

But children are not protected by the stiffness of adults. If we press our kind of knowledge into children, our concepts can invade and poison their metabolic and limb system. You can see how important it is to recognize, from practical experience, how much head knowledge we can expect children to absorb without exposing them to the dangers of being poisoned in the metabolic-limb organization.

So it is in teachers’ hands to promote either health or illness in children. If teachers insist on making students smart intellectually according to modern standards, if they crams children’s heads with all sorts of intellectuality, they prevent subconscious forces of wisdom from permeating those children. Cosmic wisdom, on the other hand, is immediately set in motion when children run around and move more or less rhythmically. Because of its unique position between head and limb-metabolism, rhythmic activity brings about physical unity with the cosmic forces of wisdom. Herbert Spencer was quite correct when he spoke of the negative effects of a monastic education aimed at making the young excel intellectually. He pointed out that in later years those scholars would be unable to use their intellectual prowess, because during their school years they had been impregnated with the seeds of all sorts of illnesses.

These matters cannot be weighed by some special scales. They are revealed only to an open mind and to the kind of flexible thinking achieved through anthroposophic training; this kind of thinking must stay in touch with practical life. So much for the importance of teachers getting to know the fundamentals that govern health and illness in human beings. Here it must be emphasized again that, to avoid becoming trapped by external criteria and fixed concepts, you must learn to recognize the ever-changing processes of human nature, which always tend toward either health or illness. Teachers will encounter these things in their classes, and they must learn to deal with them correctly. We will go into more detail when we focus on the changing stages of the child and the growing human being.

Sechster Vortrag

In den Betrachtungen von gestern und heute will ich nicht etwa schon etwas Spezielles über Gesundheits- und Krankheitslehre sagen, sondern zunächst nur dasjenige, was die Notwendigkeit darlegen wird, daß sich der Lehrende und Unterrichtende auf Wege begeben muß, die ihn zu einem Durchschauen des Gesundenden und Krankmachenden im Menschen führen. Der Unterrichts- und Erziehungskünstler muß ja vor allen anderen Dingen wirklich in die menschliche Gesamtorganisation hineinschauen können, und er darf sich nicht den unbefangenen, man möchte sagen, instinktiv-intuitiven Blick für diese menschliche Gesamtorganisation stören lassen durch allerlei abstrakte pädagogische und didaktische Regeln. Die machen ihn dem Kinde gegenüber nur befangen. Er muß ganz frei dem Kinde gegenüberstehen.

Nun hört man ja besonders in Mitteleuropa, ich weiß nicht, ob es in Westeuropa auch so ist, sehr häufig den Satz anführen: es gäbe nur eine Gesundheit und sehr, sehr viele Krankheiten. Dieser Ausspruch, an den vielfach geglaubt wird, kann aber doch einer wirklichen Menschenerkenntnis gegenüber nicht bestehen, denn der Mensch ist so individuell, so als besonderes Wesen gestaltet, daß eigentlich im Grunde genommen jeder und auch schon jedes Kind seine eigene Gesundheit hat, eine ganz besonders modifizierte Gesundheit. Und man kann sagen: So viele Menschen es gibt, so viele Gesundheitsverhältnisse und Krankheitsverhältnisse gibt es. - Das schon weist uns darauf hin, wie wir unser Augenmerk immer darauf lenken müssen, die besondere individuelle Natur des Menschen zu erkennen.

Davon aber kann nur dann die Rede sein, wenn der Mensch imstande sein wird, dasjenige, was er im anderen Menschen vor sich hat, wirklich seiner Ganzheit, seiner Totalität nach zu betrachten. In dem Menschen, dem wir im Leben gegenüberstehen, haben wir ein Ineinanderwirken von Geistig-Seelischem und Physisch-Leiblichem vor uns, gerade so, wie wir im Wasser Sauerstoff und Wasserstoff vor uns haben. Und in dem, was als Mensch vor uns steht, kann das Geistig-Seelische und das Physisch-Leibliche unmittelbar ebensowenig angeschaut werden wie im Wasser der Wasserstoff und der Sauerstoff.

Man muß, um die beiden Wesensglieder des Menschen richtig zusammenzuschauen, sie eben erst kennen. Und man kann sie nicht aus der gewöhnlichen Lebenserkenntnis heraus erkennen. Heute betrachtet man ja den Menschen auf der einen Seite so, daß man ihn in der Physiologie und Anatomie so betrachtet, wie er als leibliches Wesen vor uns steht, und man liebt es ganz besonders, die Physiologie und die Anatomie nach dem aufzubauen, was man nun nicht mehr als den konkreten Menschen vor sich hat, sondern als den Leichnam, wo das Geistig-Seelische weg ist.

Und auf der anderen Seite betrachtet man den Menschen nach dem, was er in seinem Inneren erleben kann. Aber in unserer naturalistisch-intellektualistischen Zeitperiode bemerkt ja der Mensch, indem er in sein Inneres hineinschaut, eigentlich nur noch Abstraktionen, nur noch ganz dünne, kalte Vorstellungen. Er wird nur warm, wenn er auf eine ihm unerklärliche Weise dann zum Fühlen und zu den Willensimpulsen kommt. Die durchschaut er aber wieder nicht. Die dringen als unbestimmte Wogen aus seinem Inneren herauf. Beim Hineinschauen in das Innere wird er nur die ganz dünnen, kalten Gedanken gewahr.

Sehen Sie, daß der Mensch, wenn er durch Innenschau diese kalten, blassen, dünnen Gedanken wahrnimmt, ja kein Wirklichkeitsgefühl bekommen kann, kein Realitätsgefühl, das ist eigentlich ganz selbstverständlich. Und ich werde jetzt etwas aussprechen, was der heutigen Lebensauffassung etwas paradox erscheint, aber was doch eben durchaus der Wahrheit entspricht. Man wird nämlich materialistisch gestimmt heute wegen einer zu hohen, nämlich einer zu dünnen Geistigkeit, weil dasjenige, was man im Inneren sieht, wirklich keinen Realitätscharakter mehr hat. Und gerade diejenigen Menschen unserer Kulturperiode sind ja die stärksten Materialisten geworden, die in den abstraktesten Gedanken leben. Man wird gerade durch die heutige Geistigkeit zum Materialisten. Und umgekehrt, diejenigen Menschen, welche wenig angekränkelt sind von des Gedankens Blässe, wie er in unserer Zeit hervorgebracht wird, die sich wenig einleben in die gegenwärtige Art des schulmäßigen, des wissenschaftlichen Denkens, die sich mehr an die äußeren, materiellen Vorgänge halten, die ahnen in diesen äußeren materiellen Vorgängen Geheimnisvolles genug. In unseren Gedanken ist nicht viel Geheimnisvolles heute. Die sind recht dünn, durchsichtig, vor allen Dingen ganz abscheulich klar, deshalb aber auch nicht in der Wirklichkeit stehend. Die materiellen Vorgänge draußen, die sind aber schon geheimnisvoll; die kann man nicht nur in Klarheit anschauen, sondern man kann sie auch bewundern, an die kann sich auch das Gefühl anheften. Daher werden diejenigen, die wenig angekränkelt sind von unserem heutigen Gedankenleben, die es sich nicht so unbequem gemacht haben, die Wissenschaft der heutigen Zeit zu studieren, sich mehr an das Materielle, an das geheimnisvoll Materielle halten. Und wenn sie dann doch die Sehnsucht haben, etwas vom Geist zu erkennen, dann wollen sie diesen Geist auch als etwas Materielles hinstellen. Und die werden Spiritisten. Man wird aus der heutigen abstrakten naturwissenschaftlichen Erkenntnis heraus nicht Spiritist, sondern Materialist; man wird aber gerade aus dem Hinneigen zum Materiellen heute Spiritist. Das ist das Eigentümliche, Paradoxe unserer Zeit, daß die am Materialismus hängenden Menschen, wenn sie noch Sehnsucht haben nach dem Geiste, Spiritisten werden. Sie wollen den Geist auch in materieller Form, in materiellen Erscheinungen hingestellt haben. Und diejenigen, welche sich in die Wissenschaft der heutigen Zeit einleben, die werden Materialisten. Aber man kann weder mit Materialismus noch mit Spiritismus den Menschen erkennen, sondern man kann den Menschen nur erkennen, wenn man in dem, was vor uns steht, das Geistig-Seelische und das Physisch-Leibliche ineinanderschauen kann, wenn man in jedem Organ und im ganzen Menschen immer die innige Durchdringung von Physisch-Leiblichem und Seelisch-Geistigem sieht.

Der Mensch spricht heute von der Seele und vom Geist, gewiß; er spricht vom Leib und vom Körper. Und dann stellt er große Philosophien an, welches Verhältnis zwischen der Seele und zwischen dem Leibe besteht. Da werden von den gescheitesten Menschen ausführliche Theorien aufgestellt. Die Theorien sind sehr gescheit, sehr scharfsinnig, aber sie können ja nicht die Wirklichkeit berühren, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil sich die Wirklichkeit nur ergibt, wenn man in dem vollen Menschen, in dem ganzen Menschen, in unmittelbarer Anschauung das Geistig-Seelische und das Physisch-Leibliche sich durchdringend, durchschauen kann. Und wer die Menschenerkenntnis von heute recht betrachtet, der wird ja auch finden, wie grau und nebulos sowohl die äußere Menschenerkenntnis wie auch die innere ist.

Wenn der Mensch heute den Menschen betrachtet, der vor ihm steht, dann sagt er: Das ist ein Ganzes. -- Man betrachtet ihn als ein Ganzes, weil er durch die Haut schön abgeschlossen ist. Aber man berücksichtigt wenig, wie ja diese Einheit eigentlich nur dadurch eine Einheit ist, daß die mannigfaltigsten Organe in dieser Einheit zusammenwirken. Man kann ja die Einheit nur erfassen, wenn man sieht, wie die mannigfaltigsten Organe zu dieser Einheit zusammenwirken. Und wenn heute jemand spricht, daß der Mensch doch nicht so von vornherein als eine Einheit angesehen werden kann, dann kommen die Gegner und sagen: Ja, ihr zerstört die Einheit des Menschen; man muß ihn als eine Einheit betrachten. — Aber diese Einheit bleibt ja ein ganz abstrakter "Gedanke, wenn man sie in der eigenen Vorstellung nicht selber aus den konkreten Gliedern, die im Menschen enthalten sind, aufbauen, harmonisieren kann.

Und wiederum, wenn der Mensch nach innen schaut, faßt er dasjenige, was in ihm lebt, zusammen, indem er zu sich «Ich» sagt. Leute von größter Kapazität, wie John Stuart Mill, mußten sich alle Mühe geben, Theorien darüber zu finden, was eigentlich da in diesem innerlichen Zusammengefühle enthalten ist, das sich als Ich ausdrückt. Der Mensch soll nur einmal recht achtgeben darauf, wie nebulos diese punktuelle Vorstellung «Ich» ist, was er damit eigentlich hat. Er wird schon sehen, daß er nicht mehr etwas Konkretes erfaßt in dem, was er mit dem Worte Ich bezeichnet. Im Deutschen - drei Buchstaben sind es in der Regel, und über die Buchstaben kommt der Mensch nicht hinaus. Im Englischen sollen es sogar noch weniger sein, was man mit dem Ich umfaßt, nicht einmal drei Buchstaben. Sie sehen also: nebulos beim Hineinschauen ins Innere, nebulos beim Hinausschauen in die äußere Leiblichkeit wird die heutige Menschenerkenntnis.

Gerade dieses Zusammenschauen des Geistigen mit dem Physischen, das ist es, was die Anschauungsweise des Menschen befruchtet. Die Menschen fühlen sich heute ungeheuer wohl, wenn ihnen das Goethesche Wort entgegenklingt: Materie in Geist, Geist in Materie. — Es ist schön, daß sich die Leute wohl fühlen dabei, denn es entspricht ja das wirklich einer Realität. Aber für denjenigen, der gewöhnt wird, überall das Geistige und das Physische zusammenzuschauen, für den kann das ebenso eine Trivialität sein, wenn man ihn noch zur Anerkennung dieser Selbstverständlichkeit auffordert. Und daß sich die Leute so wohl fühlen, wenn so etwas theoretisch vor sie hingestellt wird, das ist eben ein Beweis dafür, daß sie es in der Praxis nicht haben. Sehr dezidierte Theorien sind in der Regel ein Beweis dafür, daß man das Betreffende in der Praxis nicht hat, wie die Geschichte zeigt. Die Leute haben erst über das heilige Abendmahl in Theorien zu diskutieren angefangen, als sie in der Praxis der Sache nicht mehr die nötige Empfindung entgegenbrachten. Theorien stellt man in der Regel auf für das, was man nicht hat, nicht für das, was man im Leben hat.

Gerade mit dieser Gesinnung kann nun derjenige, der ein wirklicher Erziehungs- und Unterrichtskünstler sein will, an eine Menschenerkenntnis herangehen. Dann wird er aber dazu geführt, die Gliedhaftigkeit des Menschen in der Konkretheit zu erfassen, nicht ein verschwommenes Einheitsgebilde; die Einheit tritt zuletzt auch auf, aber aus dem Zusammenhang der Gliedhaftigkeit. Und da kann man dann nicht anders, als zunächst zu dem geführt werden, was ich zuerst in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln» angedeutet habe, zu der Gliederung des Menschen in drei ihrer Organisation nach verschiedene Wesensteile. Schon äußerlich zeigt sich die Kopforganisation ganz anders als, sagen wir, die Organisation, die wir sehen als die Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganisation. Ich spreche von Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganisation, weil der Stoffwechsel dann charakteristisch hervortritt, wenn der Mensch durch seine Gliedmaßen in Tätigkeit ist. Der Stoffwechsel ist ja auch morphologisch gewissermaßen die Fortsetzung nicht des ruhenden, sondern des bewegten Menschen nach innen; daher ist er reger, wenn der Mensch bewegt ist. Es ist ein innerer Zusammenhang, den man auch ganz im einzelnen nachweisen kann - ich will ihn hier nur andeuten - zwischen dem Gliedmaßenorganismus und dem Stoffwechselorganismus, so daß ich da zunächst von einer Einheit spreche: Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus. Aber an sich stellen diese beiden einander entgegengesetzte Organisationen dar.

Nehmen Sie schon das Äußerliche, rein der Gestalt nach. Der Kopf ist, wenn wir von den Haaren absehen, die aber nach außen gehen und eigentlich etwas sind, was sich der lebendigen Organisation entzieht, die etwas Totes sind - es ist interessant, die Haare zu betrachten, aber es würde uns im gegenwärtigen Augenblicke zu weit führen -, der Kopf ist von einer Skelettkapsel umgeben, und die ist an der Peripherie am mächtigsten ausgebildet; während dasjenige, was das Weiche, Lebendige des Hauptes, des Kopfes ist, im Inneren liegt. Sehen Sie sich dagegen die Organisation des Menschen am entgegengesetzten Pole an, sehen Sie sich die Gliedmaßenorganisation an: Sie haben den Röhrenknochen, innerhalb desselben das gewöhnlich kaum bemerkte Mark, dem man für den Gesamtorganismus nicht eine solche Bedeutung zuschreibt wie dem Inneren des Kopfes; dagegen sehen Sie dasjenige, was wichtig ist für den Organismus, äußerlich angehängt. Also gerade den Gegensatz sehen wir hier ausgebildet. Und dieser Gegensatz ist durch die ganze menschliche Natur bedingt. So daß wir von zwei entgegengesetzten Naturen sprechen können: von der Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, die hauptsächlich, ich sage hauptsächlich, nicht ausschließlich, im Kopfe lokalisiert ist, und von der Stoffwechseltätigkeits-Organisation, die im Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus lokalisiert ist. Natürlich ist der Mensch in Wirklichkeit doch eine Einheit. Und wir dürfen nicht vergessen, daß wir nicht, einer gewissen schematisierenden Neigung entsprechend, jetzt wiederum drei Teile hinstellen und diese fein definieren dürfen: Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, die andere werden wir gleich kennenlernen, Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganisation; und dann feine Definitionen hinstellen, als ob das so getrennt wäre. So getrennt ist es nicht. Es findet ein fortwährender Stoffwechsel und auch eine Bewegungstätigkeit in den Muskeln des Kopfes statt und im Kopfe; aber es ist der Kopf hauptsächlich Nerven-Sinnesorganisation; und es findet auch ein Durchdringen des Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus mit Gedankenkräften statt. Aber es ist der Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus eben hauptsächlich Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus.

Und zwischen drinnen steht alles dasjenige, was man nennen kann den rhythmischen Organismus des Menschen. Er ist lokalisiert im Brustorganismus. Da haben wir die hauptsächlichsten Rhythmen, Atmungsrhythmus, Zirkulationsrhythmus voneinander differenziert; der Atmungsrhythmus langsam, der Zirkulationsrhythmus schneller; der Atmungsrhythmus in den Atemzügen bemerkbar, der Zirkulationsrhythmus im Pulsschlag. Das ist das Vermittelnde, das steht zwischen den beiden anderen Polen drinnen, das gleicht aus. Es wäre reizvoll, das alles im einzelnen durchzuführen, allein das kann man nicht immer, wenn man zu einem besonderen Zweck, wie hier zu dem pädagogischdidaktischen, die Dinge auseinandersetzt. Wenn Sie sich aber einen Sinn dafür aneignen, die Brustorganisation zu betrachten, dann werden Sie in der Skelettgestaltung, in der Gestaltung der Organe, überall den Übergang finden von der Gestalt der Kopforgane zu der Gestalt der Gliedmaßenorgane, der Stoffwechselorgane. Es steht das alles, was in der Brustorganisation ist, auch seiner Form nach, in der Mitte drinnen zwischen diesen beiden Polen der menschlichen Organisation. Zu dieser Betrachtungsweise werden wir geführt, wenn wir uns auf den Weg begeben, den Menschen nun tatsächlich seiner inneren Konfiguration nach anzuschauen und nicht einfach das nebulose Gebilde des Einheitsmenschen vor uns hinstellen.

Aber das geht viel weiter. Das geht auch in die Betätigungsweise des ganzen Menschen hinein. Und dafür möchte ich Ihnen auch ein Beispiel anführen. Man könnte unzählige solcher Beispiele anführen, aber gerade aus einem solchen Beispiel werden Sie sehen, wie notwendig es ist, daß gerade der Unterrichts- und Erziehungskünstler sich auf einen solchen Weg begibt, wie ich ihn hier darstelle. Nehmen Sie einmal an, Ste haben einen Menschen vor sich, der an Zornanwandlungen leidet. Zornanwandlungen, Zornmütigkeit beim Menschen können schon im Kinde auftreten. Man muß damit fertig werden als Erzieher, als Unterrichtskünstler. Nun, wenn man mit der heutigen Physiologie und Anatomie den Menschen betrachtet, so wird man ja allerdings noch auf der einen Seite abstrakt untersuchen, wie die Seele sich auslebt, wenn sie zornig wird, wie der Gewohnheitszorn sich äußert; das steht auf der einen Seite. Auf der anderen Seite wird man vielleicht auch wiederum dazu kommen, sich zu sagen: beim zornmütigen Menschen sondert sich Galle ab im abnormen Maße. Aber man schaut diese zwei Dinge nicht zusammen. Man schaut nicht das Geistig-Seelische des Zorns, des Ärgers, und das Leiblich-Physische, die Gallenabsonderung als eine Einheit zusammen. Nun, im normalen Menschen ist es notwendig, daß er die Gallenabsonderung hat, weil sich der Gallsaft vermischen muß mit den Stoffen, die sich seinem Organismus durch die Ernährung einverleiben. Von dem, was ganz in der Ordnung ist im normalen Organismus, von dem tut der Zornmütige zuviel, er sondert zuviel Galle ab. Und wenn er in diesem Zustande verbleibt, wird er zuletzt die Gelbsucht bekommen, wie Sie wissen.

Wir sehen durch ein Zusammenschauen des Geistig-Seelischen mit dem Physisch-Leiblichen eine Krankheitsneigung entstehen. Das allein aber genügt nicht, um die Menschennatur zu beurteilen. Während im Stoffwechselorganismus die Galle abgesondert wird, geschieht immer im Kopforganismus ein polarisch entgegengesetzter dazugehöriger Vorgang. Man betrachtet überhaupt die menschliche Natur nicht vollständig, wenn man nun wiederum nur die Aufmerksamkeit auf die Galle und auf ihre Absonderung richtet, wenn man nicht weiß: während im Stoffwechselorganismus Galle abgesondert wird, geschieht im Kopforganismus gerade das polarisch Entgegengesetzte. Da findet eine Aufnahme einer aus dem übrigen Organismus zubereiteten milchsaftähnlichen Flüssigkeit statt. Während also im abnormen Maße im Stoffwechselorganismus Gallenflüssigkeit abgesondert wird, entnimmt der Kopf aus dem übrigen Organismus, indem er sie aufsaugt, eine milchsaftähnliche Flüssigkeit. Dadurch entwickelt der Zornmütige einen Hang; seinen Kopf mit dem auszustaffieren; allerdings, wenn die Zornanwandlung vorüber ist, dann fühlt er so etwas, wie wenn sein Kopf zerspringen würde. Und während ihm einerseits durch die Gallenabsonderung etwas gegeben werden kann in der milchsaftähnlichen Flüssigkeit, zeigt sich andererseits, wenn der Zorn im Abfluten ist, daß er durch dasjenige, was sich in seinem Kopf ansammelte, ganz blau wird. -— Wir sehen also, auch wenn wir nicht bloß auf die Form, sondern auch auf die Vorgänge schauen, eine Polarität zwischen der Kopfoder Nerven-Sinnesorganisation und der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganisation. Zwischen beiden ist die rhythmisch-regulierende Organisation, eben die rhythmische Organisation, die in Atmung und Zirkulation besteht.

So steht gewissermaßen in der Mitte der menschlichen Natur die rnythmische Organisation in Atmungsrhythmus, in Zirkulationsrhythmus. Wenn man nun versucht, seine Menschenerkenntnis nicht so bequem auszugestalten, daß man sie nach den ruhenden Organen richtet, und diese möglichst in scharfen Konturen aufzeichnen will, sondern wenn man seine Menschenerkenntnis innerlich beweglich macht, so wird man vor allen Dingen von der Beziehung, dem Verhältnis gefangengenommen werden, das zwischen den drei angeführten Gliedern der menschlichen Natur besteht. Man wird sehen, wenn man den Blick zu der rhythmischen Atmungstätigkeit hinwendet, wie beim Einatmen gewissermaßen der Atmungsstoß bis zu jener Flüssigkeit geführt wird, die den Rückenmarkskanal ausfüllt. Diese Flüssigkeit setzt, indem sie den Atmungsrhythmus empfängt, diesen Atmungsrhythmus bis in die Flüssigkeit des Gehirns hinein fort, welche die verschiedenen Hirnhöhlen ausfüllt, und durch das Anschlagen dieser Atmung an das Gehirn wird fortwährend dasjenige aus der Atmung heraus angeregt, was den Menschen bereit macht, durch seine Nerven-Sinnesorganisation, durch die Kopforganisation zu wirken. Es ist wie eine Umsetzung des Atmungsprozesses durch den Rückenmarkskanal mit Hilfe der Rückenmarksund Gehirnflüssigkeit in den Kopf hinein, was von diesem mittleren Gliede, von dem Atmungsgliede an Reizen fortwährend in den Kopf hinein will.

Und wiederum, wenn wir nach unten gehen, wenn wir sehen, wie der Atmungsrhythmus sich gewissermaßen mehr erregt zum Pulsrhythmus, wie er in den Zirkulationsrhythmus übergeht, so lernen wir darauf blicken, wie nun wiederum bei der Ausatmung, wenn die Gehirnflüssigkeit und Rückenmarksflüssigkeit nach unten stößt, der Zirkulationsrhythmus auf die Stoffwechseltätigkeit wirkt, und wir sehen den Zirkulationsrhythmus ineinanderwirken mit dem Sinnes-Nervenorganismus und dem Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus auf dem Umwege durch eine lebendige, plastisch-künstlerische Betrachtung der Atmungs-Zirkulationsorganisation. Wir sehen, wie sie sich polarisch nach der einen Seite hin in das Gehirn, in die Kopforganisation erstreckt, auf der anderen Seite ganz anders, polarisch entgegengesetzt in dem Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus sich äußert. Aber wenn man sich einmal auf den Weg begibt, der in dieser Art den Menschen lebendig auffaßt, dann kommt man weiter. Dann wendet man den Blick auf den Atmungs-Zirkulationsrhythmus hin und verschafft sich Vorstellungen, die sich gewissermaßen mit dem Atmungs-Zirkulationsrhythmus decken. Diese Vorstellungen sind ja nicht so bequem, daß man sie aufzeichnen kann, aber dieses Aufzeichnen und Einteilen, das ist überhaupt etwas Mißliches gegenüber der immer beweglichen Menschennatur.

Als wir uns, lassen Sie mich das einschalten, noch innerhalb der Theosophischen Gesellschaft bewegten mit der anthroposophischen Erkenntnis und Lebenspraxis, da traf man überall, wenn man in die Zweige kam, Tabellen, ein, zwei, drei, vier, fünf, manchmal ganz ungeheuer viele Zahlen und überall zu diesen Zahlen Termini dazu. Da war alles gegliedert. Man hatte so eine schematische Leiter. An dieser hätte man hinaufsteigen können in die höchsten Regionen des Daseins. Manche stellten sich auch so etwas wie ein Kletterturnen vor von der physischen Welt hinauf in die höchsten Regionen des Daseins. Es war alles so hübsch eingekapselt. Das kann für denjenigen, der weiß, daß man die bewegliche Menschennatur übersinnlich wirklich nur so erfassen kann, daß man sich sein Vorstellungsleben beweglich erhält, das kann so werden - ja, es zuckte einem furchtbar in den Gliedern, wenn man in diese Zweige hineinkam, man konnte es gar nicht aushalten, man hätte immer gleich hinauslaufen mögen, bloß wegen dieser Denkgewohnheiten. Nun, das ist es eben, worauf es ankommt, daß man zu einer wirklichen Menschenerkenntnis den Weg suchen muß durch Beweglichmachen seiner Vorstellungen. Dadurch gelangt man aber von dem, was ich schon angeführt habe, dann noch um einen Schritt weiter.

Wenn man versucht, Vorstellungen zu gewinnen über diesen Atmungs-Zirkulationsrhythmus, wie er sich nach oben modifiziert und metamorphosiert, dann kommt man dazu, sich zu sagen, indem man jetzt nicht schematisch, sondern nur andeutend zeichnet (es wird gezeichnet): man hat hier etwas wie Vorstellungsstränge, durch die man sich in einer ziemlich robusten Art vorstellt, was durch die Atmungswege, Zirkulationswege sich für Prozesse abspielen, und man erfaßt dann das, was da materiell ist in der Blutflüssigkeit, in der viel feineren imponderablen Nerven-Ätherflüssigkeit, könnte man sagen. Aber wenn man nun den Menschen weiter vorstellt, indem man den Blick von der Brustorganisation im Menschen nach aufwärts wendet, so sieht man sich gedrängt, seine Vorstellungen selber zu zerfasern, sie netzförmig zu gestalten. Und dadurch kommt man dazu, etwas, was äußerlich real, wirklich ist, tatsächlich durch seine nach oben hin modifizierten Vorstellungen zu erfassen. Man kommt dazu, diese robusten, dicken Stränge zu zerfasern, und man kommt allmählich durch das Vorstellen dieses Prozesses in dasjenige hinein, was die sogenannte weiße, faserige Hirnsubstanz ist, die unter der grauen Masse liegt. Man wird mit seinen Vorstellungen so beweglich, wie die menschliche Natur selber beweglich ist.

Und wiederum, wenn man dem Menschen die Ehre antut, ihn nicht einfach so robust anzuschauen: er ist eine Einheit, sondern, wenn man auf seine Brust schaut, hier diese robusten Vorstellungen hat, dann, indem man sich dem Kopf nähert, die Vorstellungen zerfasert, kommt man gerade dadurch, indem die Vorstellungen sich zerfasern, in das materielle Leben hinein, was einem dann in den Nervenfasern und in ihren Verwebungen abgebildet wird.

Wenn man nun mit seinem Vorstellen nach abwärts geht, dann kommt man dazu, das nicht zu können, die Vorstellungen zu zerfasern, so daß sie ein Gewebe bilden, das man dann im Nervensystem wiederfindet, sondern dann kommt man dazu, indem man versucht, die robusten Stränge nach unten fortzusetzen, daß man sie verliert. Sie hören auf, sie wollen sich nicht fortsetzen, sie hören auf. Man kommt in ein Vorstellen hinein, das sich nicht mehr recht mit einem Materiellen decken will, weil einem das Materielle flüssig wird. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie sich das Gehirn anschauen, wie es sich im Rückenmark durch die zwölf Brustwirbel, Lendenwirbel, Kreuzwirbel und so weiter fortsetzt, so lösen sich die Nervenmassen, die jetzt außen weiß und innen grau sind, gegen das Stoffwechselgebiet hin auf. Gewissermaßen verliert sich die Möglichkeit in diesem Gefühl, sich das materiell vorzustellen. Man kann nicht mit gleichartig bleibenden Vorstellungen den ganzen Menschen umfassen. Man muß sein Vorstellungsleben innerlich beweglich machen. Indem man beim Menschen hinaufschaut, werden die Vorstellungen zu etwas anderem, als wenn man beim Menschen herunterschaut. Es ist eine Art Nachschaffen desjenigen möglich, was beim Menschen beweglich geworden ist. — Sie sehen, es ist ein Anfang zu einer künstlerischen Tätigkeit, die dann gewissermaßen den Erkennenden in dasjenige hineinstellt, was man als materielles Gebiet wirklich draußen am Menschen in der Welt sieht. Man hat, möchte man sagen, nicht auf der einen Seite die derbmaterielle konkrete Welt und dann das abstrakte Vorstellen, sondern man taucht unter in die menschliche Natur. Und das, was man in den Vorstellungen hat, das wird selber so, daß es lebendig wird und das menschliche Leben mitlebt. Auf eine andere Weise kann man insbesondere das, was man als Erziehungs- und Unterrichtskünstler nötig hat, am Menschen gar nicht erkennen. Man muß in dieser Weise selber beweglich werden, um den Menschen wirklich zu erkennen. Dann wird man aber auch richtig herausfinden, wie diese drei Glieder der menschlichen Organisation zusammenwirken müssen, um das menschliche gesunde Gleichgewicht zu erzeugen. Und man wird auf dasjenige aufmerksam werden können, was in gestörtem Gleichgewicht die Neigungen zu allerlei Krankhaftem hervorbringt. Man wird eine lebendige Anschauung von dem Wege zum Gesundenden und dem Erkrankenden im Menschen gewinnen.

Das wird namentlich dann wichtig, wenn man den menschlichen Lebenslauf ins Auge faßt. Denn in einer anderen Weise wirken im Kinde, in einer anderen Weise im reifen Alter und in einer noch anderen Weise im Greisenalter diese drei Glieder des menschlichen Organismus zusammen. Beim Kinde ist es so, daß die geistig-seelische Wesenheit in einer ganz anderen Art in die physisch-leibliche hineinwirkt, so daß zwischen diesen drei Gliedern ein ganz anderes Zusammenwirken zustande kommt als beim reifen Menschen und beim Greise. Und auf dieses verschiedene Wirken wird man hinschauen müssen. Wenn man überhaupt den Weg zu einem solchen Vorstellen nimmt, wird man es allmählich dazu bringen, auch den menschlichen Lebenslauf in einer anderen Weise zu erfassen, als man das gewöhnt ist.

Man hat es mir besonders übelgenommen, daß ich in meinem Buche «Die geistige Führung des Menschen und der Menschheit» darauf aufmerksam gemacht habe, wie das Kind eine Weisheit besitzt, die der Erwachsene eigentlich gar nicht mehr hat. Gewiß, ich will ja der Weisheit, der Gescheitheit unserer erwachsenen Leute nicht nahetreten; aber denken Sie nur einmal, wenn Sie all diese Weisheit im späteren Leben aufbringen müßten, die imstande ist, aus der verhältnismäßigen Unbestimmtheit der Gehirnmasse, des übrigen Organismus weisheitsvoll den ganzen Organismus zu durchdringen, wie wir es im Kindheitsalter instinktiv machen, wir würden schlecht damit fahren. Allerdings bleibt das beim Kinde alles im Unbewußten stecken, wie es das Gehirn plastisch herausgestaltet, wie es das übrige plastisch herausgestaltet; aber es ist doch vorhanden, und man sieht, daß es vorhanden ist, wenn man mit den Mitteln des Erkennens, die ich Ihnen in den letzten Tagen geschildert habe, herangeht, den ganzen Lebenslauf zu betrachten; wenn man namentlich ein wirkliches Organ entwickelt für die kindlichen Träume. Die Erwachsenen weisen sie ja heute meistens als unsinnig zurück; aber diese kindlichen Träume, in ihrer Wesenheit betrachtet, sind außerordentlich interessant, sind ganz anders als die Träume des Erwachsenen. Sie sind so, daß das Kind tatsächlich vielfach von dem träumt es kann es nur nicht ausdrücken, aber wir können dahin kommen, das Kind nach dieser Richtung zu verstehen -, daß das Kind in Gestalten von jener Weisheit träumt, durch die es sich sein Gehirn und seinen übrigen Organismus plastisch gestaltet. Würde man manchen Kindestraum mit einer inneren Liebe nach dieser Richtung hin verfolgen, man würde schon sehen, wie das Kind, ich möchte sagen, Urweisheit träumt, die da waltet. Von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus, verzeihen Sie den harten Ausdruck, ist das Kind viel weiser, viel gescheiter als der erwachsene Mensch. Und der Erziehende sollte sich eigentlich bewußt sein, wenn er über die Schwelle der Schultüre schreitet, daß das Kind nach dieser Richtung viel mehr Weisheit hat als er. Er hat es ja schon abgelegt und ausgebildet; was er nun als die mittlerweile errungene Erfahrungsweiisheit, Erfahrungsgescheitheit hat, läßt sich doch nicht gut mit dem vergleichen, was er damals als Weisheit hatte. Wenn man daher die menschlichen Träume des späteren Alters nimmt, enthalten sie nicht mehr das, was das kindliche Träumen hat, sondern dasjenige, was der Mensch von dem äußeren Leben in das Träumen hineinträgt. Ich habe darüber von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus gesprochen. Träumt der erwachsene Mensch, trägt er seine Tagesweisheit auch in das Nachtleben hinein; die wirkt wiederum auf ihn zurück, während auf das Kind eine viel höhere Weisheit wirkt. Die hat das Kind nicht im Bewußtsein, aber im Unbewußten empfindet das Kind diese Weisheit, und wenn es in der Schule sitzt, so hat es ein unbewußtes Gefühl, daß es diese Weisheit in sich hat, die der Lehrer nicht hat, die er schon abgelegt hat. Der Lehrer hält sich äußerlich für viel weiser als das Kind. Es ist natürlich, er würde sich ja sonst nicht recht als Lehrer fühlen können; aber er hat seine Weisheit eben im Bewußtsein. Das hat er ja vor dem Kinde voraus. Aber sie ist nicht so umfassend, nicht so großartig wie die Weisheit des Kindes. Würde man dasjenige, was das Kind unbewußt als Weisheit in sich trägt, aussprechen, und würde man dasjenige, was der Lehrer verloren hat, auch wiederum in Worte kleiden, so würde etwas sehr Sonderbares herauskommen, das aber eine große Wichtigkeit hat für das wirklich imponderable Leben in der Schule. Da würde man nämlich auf das Folgende kommen: Wenn der Lehrer mit seiner in der Welt erworbenen Gescheitheit die Schule betritt, ist er durch diese abstrakte Gescheitheit von heute, das kommt vor, ein ziemlich trockener, philiströser Mensch geworden, der das auch zuweilen schon im Äußeren zeigt. Das Kind hat ja noch all die Munterkeit, die aus jener Weisheit kommt, von der ich gesprochen habe. Man verbietet ihm natürlich, seine Empfindung auszudrücken. Und so kommt das zustande, daß in der Schule das Lehrerurteil waltet: Der Lehrer ist gescheit, das Kind ist dumm. — Aber im Unterbewußten ist es anders. Und wenn in den Träumen erst gesprochen würde, so wäre es wieder anders. Im Unterbewußten kommt das zustande, daß die Kinder unbewußt denken: Wie ist doch der Lehrer dumm - und der Lehrer denkt unbewußt: Wie sind doch die Kinder gescheit! - In dem ganzen Ensemble spielt dasjenige, was da waltet in einer Schulklasse, eben eine außerordentlich große Rolle.

Man muß sich durchaus klar darüber sein, daß eigentlich das Kind, indem es sich so verhält, wie ich es geschildert habe, immer ein wenig in einer Art von innerem Hochmut, der aber unbewußt bleibt, in einer Belustigungsstimmung dem Lehrer auf ganz naturgemäße Weise gegenüberstehen muß; denn es kann ja nicht anders, als empfinden im Hintergrunde seiner kindlichen Natur das weisheitsvolle, den Menschen aufbauende Wesen, und das andere — wie wenig eigentlich dann daraus geworden ist, wie man ja sieht; so urteilt dann ja die unbewußte Natur des Kindes -, wenn der Lehrer hereintritt mit seiner Steifigkeit, mit seiner durch abstrakt-intellektualistische Begriffe moros gewordenen Signatur, mit dem Rock, der in der Bibliothek so staubig geworden ist, daß man ihn gar niemals genügend ausbürsten kann, da, nicht wahr, empfindet das Kind in der allerintensivsten Weise dasjenige, was ich ein belustigendes Erkennen nennen möchte.

Das ist dasjenige, was man dem Kinde gegenüber tatsächlich immer empfinden muß, und was in einer gewissen Weise aus der menschlichen Natur heraus durchaus berechtigt ist. Das Kind rettet sich ja eigentlich seine Gesundheit dadurch; denn es ist ganz sicher, das Kind träumt nicht in erhebender Weise von Lehrern, sondern es träumt von jener Weisheit, die ich geschildert habe, die es durchwebt, durchströmt. Beim Lehrer entwickelt sich etwas Entgegengesetztes im Unterbewußtsein, das auch eine Möglichkeit in den Imponderabilien der Schulstube ist. Aber es ist deutlich da. Beim Kinde ist es mehr, ich möchte sagen, ein Erkenntnisverhältnis. Beim Lehrer wird es zu etwas Begehrlichem, wird es zu etwas, was im Begehrungsvermögen sich äußert. Der Lehrer denkt in seinem Unterbewußtsein und träumt auch davon — was er sich natürlich vermöge seiner schulmäßigen Zivilisation im Oberbewußtsein ganz und gar nicht gesteht -, er träumt eigentlich davon, etwas von dem zu haben, was an Kräften der kindlichen Natur eigen ist. Man würde schon sehen, wenn man gerade daraufhin manchmal mit etwas mehr Geist, als es heute geschieht, die menschlichen Seelen psychoanalysieren würde, welche Rolle im unterbewußten Leben des Lehrers diese munteren, frischen Wachstumskräfte und sonstigen menschlichen Kräfte des Kindes spielen.

Das aber wirkt alles im imponderablen Leben, das sind Kräfte, die sich wirklich in der Schulstube entwickeln. Und man kann schon sagen, sieht man etwas hinter die Kulissen des gewöhnlichen kindlichen Daseins, dann wirkt das Kind in der Schulstube so, daß es sein Interesse von dem Lehrer wegwendet und frägt: Was ist denn in diesem Individuum aus all dem geworden, was wir in uns haben? — Aber beim Lehrer wirkt das auf das Begehrungsvermögen. Er beginnt im Unterbewußten die Kinder zu vampyrisieren. Unter dem Bewußtsein will er sich die Kräfte der Kinder aneignen. Und würde man genauer zusehen, so würde man sehen, wie stark oft dieses Vampyrisieren hinter den Kulissen des physischen Daseins wirkt. Man würde sehen, woher die Schwächlichkeit mancher Kinder — allerdings müssen die Dinge wiederum intim betrachtet werden - und die krankhafte Veranlagung der Kinder dieser oder jener Schulstube kommen. Man würde sich nur, wenn man freien, offenen Blick dazu hat, die Figuration des Lehrers oder der Lehrerin anzuschauen brauchen, dann würde man manchen Einblick in die gesunden und kranken Neigungen der Kinder in der Schulstube bekommen.

Wir können so etwas als Erziehungs- und Unterrichtskünstler nicht anders überwinden, als wenn wir uns von einer Menschenerkenntnis erfüllen, die — weil sie innerlich beweglich ist, weil sie selber geistigseelisch ein Organismus ist, der dem Menschenorganismus nachgebildet ist in der Art, wie ich das gezeigt habe -, die sich zugleich mit Menschenliebe, mit wahrer Menschenliebe verbindet, die die verschiedenen einseitigen Kräfte der menschlichen Natur eben überwindet und harmonisiert. Dadurch, daß man sich eine solche Menschenerkenntnis aneignet, kommt man auch darauf, wie nicht nur die menschliche Natur sich in verschiedener Weise in verschiedenen menschlichen Individuen ausspricht, sondern wie sich die menschliche Natur in ganz anderer Weise in der Kindheit, im reifen Alter, im Greisenalter ausspricht. Die drei Glieder der Menschennatur wirken eben ganz verschieden ineinander, und sie müssen aufeinander abgestimmt werden.

Das wird zum Beispiel sehr real, wenn wir daran denken müssen, die Zeit die wir zum Unterrichten und Erziehen zur Verfügung haben, in der richtigen Weise einzuteilen. Wir müssen ja selbstverständlich den ganzen Menschen in das Erziehungs- und Unterrichtswesen hineinstellen, also sowohl seine Kopfnatur wie auch seine Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselnatur, und da ja wiederum in jedem einzelnen Gliede die anderen Prozesse der anderen Glieder auch vor sich gehen, müssen wir das berücksichtigen. Im Kopfe finden natürlich auch fortwährend Stoffwechselvorgänge statt.

Haben wir es nun nötig, für gewisse unterrichtliche, erzieherische Formalia das Kind ruhig sitzen zu haben in der Klasse, wir werden davon noch sprechen, auch auf den hygienisch eingerichteten Bänken, dann behandeln wir das Kind aber immerhin so, daß es still sitzt, daß also nicht im Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus die Tätigkeit wirkt, sondern daß alles dasjenige, was wirkt, aus dem Kopf herausgeholt werden muß. Das ist eine Einseitigkeit, in die wir das Kind versetzen. Wir gleichen das wiederum aus, indem wir nachher, mit Recht nachher, den Kopf entlasten von seiner Tätigkeit und den GliedmaßenStoffwechselorganismus in Regsamkeit bringen, indem wir das Kind zur Gymnastik bringen.

Wenn man sich bewußt ist, wie polarisch entgegengesetzt die Prozesse im Kopforganismus und im Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus sind, wird man gar wohl begreifen, wie wichtig es ist, daß man auch in dieser Weise in der rechten Art abwechselt. Aber wenn wir dann die Kinder haben turnen, springen lassen, alle möglichen Übungen haben machen lassen und sie dann wiederum zurücknehmen in die Klasse und in der Klasse weiter unterrichten, ja, wie ist es denn dann?

Sehen Sie, während der Mensch seinen Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus in Regsamkeit hat, da sind allerdings diejenigen Gedanken, die künstlich zwischen Geburt und Tod in den Kopf hineingebracht werden, aus dem Kopf draußen. Das Kind springt herum, bewegt sich, bringt den Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus in Bewegung. Die während des physischen Erdenlebens eingepflanzten Gedanken, die gehen zurück. Aber dasjenige, was sonst in den Träumen figuriert, diese übersinnliche Weisheit ist jetzt auf unbewußte Art im Kopfe drinnen, macht sich gerade im Kopfe geltend. Führen wir daher das Kind nach der Gymnastik wiederum zurück in die Schulstube, dann setzen wir ihm etwas, was im Unterbewußten für das Kind minderwertig ist, an die Stelle desjenigen, was es vorher gehabt hat während der gymnastischen Übungen. Denn während der gymnastischen Übungen wirkt nicht nur das Sinnliche auf das Kind erziehend, sondern auch das Übersinnliche, das während der gymnastischen Übungen ganz besonderen Anlaß hat. Daher wird das Kind in der folgenden Stunde innerlich unwillig. Es äußert vielleicht den Unwillen nicht so stark, aber es wird innerlich unwillig. Und wir verderben es, wir veranlagen in ihm Krankheitsneigungen dadurch, daß wir wiederum auf die gymnastischen Übungen den gewöhnlichen Unterricht hinaufpfropfen.

Es ist das ja eine Tatsache, die sogar häufig schon äußerlich bemerkt worden ist, wie mir ein Physiologe versicherte. Aber hier haben Sie aus anthroposophischer Geistesforschung die Gründe dafür, daß wir sehen können, wie wir allerdings die Neigungen zum Gesunden dadurch fördern können, daß wir uns als Lehrer und Erziehungskünstler in der richtigen Weise Menschenerkenntnis erwerben. Natürlich, wenn wir es nicht in der richtigen Weise machen, erzeugen wir allerlei Krankheitsanlagen. Das müssen wir durchaus bedenken. Denn, Sie haben ja bemerkt, ich will nicht in Glorifizierung desjenigen verfallen, was der Mensch sich als seine Lebensweisheit aneignet; sie würde ja nicht ausreichen, um die menschliche Organisation im künftigen Alter plastisch zu gestalten. Aber würden wir nicht im späteren, reifen Alter in der Organisation schon so versteift sein, daß dasjenige, was wir da in den Kopf hineinbringen als äußerliche Weisheit, die auf naturalistisch-intellektualistische Art erworben wird, würde das nicht alles in der richtigen Weise als Erinnerungsvorstellung zurückstrahlen, so würde es später in den übrigen Organismus hinunterströmen. Und dasjenige, so paradox es wiederum klingt, was nach der normalen Organisation des Menschen im Kopforganismus bleiben soll, wenn es in den GliedmaßenStoffwechselorganismus hinunterströmt, macht es den Menschen krank, ist wie Gift. Verstandesweisheit ist in der Tat eine Art von Gift, sobald sie an den unrichtigen Ort kommt, sobald sie wenigstens in den Stoffwechselorganismus hineinkommt. Wir können nur dadurch mit der Verstandesweisheit leben, daß dieses Gift - in ganz technischem Sinne, nicht in moralischer Beurteilung sage ich das -, daß dieses Gift nicht in unseren Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus hinunterdringt. Da wirkt es furchtbar zerstörerisch.

Aber beim Kinde ist diese Versteiftheit nicht da. Wenn wir da mit unserer heutigen reifen Weisheit kommen, so dringt dieses Gift hinunter und vergiftet in der Tat den Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus. Sie sehen, es ist notwendig, aus der unmittelbaren Lebenspraxis heraus wissen zu lernen, wieviel man diesem Kinderhaupte zumuten darf, damit man nicht zuviel hineinpreßt, was dann nicht mehr aufgehalten wird und was dann in den Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus hinuntergeht.

Man hat es also als Lehrer und Erziehungskünstler in der Hand, entweder gesundend oder krankmachend auf den Kindesorganismus zu wirken, Und will man ein Kind nach der heutigen Lebensweisheit ganz besonders gescheit machen, setzt man es also immer hin und pfropft soviel als irgend möglich in es hinein beim Sitzen, dann tritt das andere ein: dann verhindert man im Kind, daß die unbewußte Weisheit in ihm wirkt. Denn diese unbewußte Weisheit wirkt ja gerade, wenn es sich tummelt, wenn es mehr oder weniger rhythmische Bewegungen macht; denn der Rhythmus fördert das Sich-Verbinden des Organismus mit der unbewußten Weisheit durch die eigentümliche Mittelstellung, die dieser rhythmische Organismus zwischen Kopforganisation und Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganisation angenommen hat. So daß sich schon das herausstellt, wenn wir diese Klostererziehung anwenden, von der Herbert Spencer spricht, um die Kinder und jungen Leute ganz besonders gescheit zu machen, dann machen wir sie dadurch so, daß wir sie mit Krankheitsneigungen ausstatten, durch die sie im späteren Leben mit der Weisheit, die wir ihnen beibringen, gar nichts mehr anzufangen wissen.

Das sind alles Dinge, die wahrhaftig nicht mit der Waage abgewogen werden können, sondern nur vor einer beweglichen Vorstellungsart sich enthüllen, die sich immer ans Leben anpaßt, wie sie eben durch anthroposophische Schulung erworben werden kann. Und damit sei im allgemeinen darauf hingedeutet, wie der Lehrer und Erziehungskünstler sich bekanntmachen muß mit den großen Grundsätzen des Gesundens und Krankens im Menschen.

Und da ist es von wesentlicher Bedeutung, zu bemerken, wie das Streben, mit seiner Anschauung, mit seinem Welterkennen nicht an dem Äußerlichen, Unbeweglichen, Fixen hängenzubleiben, sondern zu einer inneren Beweglichkeit des Denkens aufzusteigen, wie das mit der Erkenntnis all der labilen Zustände zusammenhängt, in denen die menschliche Natur sich nach der gesunden und kranken Seite äußert, und die als etwas, was er zu behandeln hat, dem Lehrer in der Schule entgegentritt.

Auf die Einzelheiten werden wir eingehen, wenn wir nun das Kind, den werdenden Menschen in den aufeinanderfolgenden Lebensaltern betrachten.

Sixth Lecture

In yesterday's and today's reflections, I do not want to say anything specific about health and disease, but rather only what will demonstrate the necessity for teachers and educators to embark on paths that will lead them to an understanding of what makes people healthy and what makes them sick. Above all else, the teaching and educational artist must be able to truly see into the overall human organization, and they must not allow their unbiased, one might say instinctive-intuitive view of this overall human organization to be disturbed by all kinds of abstract pedagogical and didactic rules. These only make them self-conscious in front of the child. They must stand completely free in front of the child.