| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture III

13 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

|---|

| So exactly does one have this tableau before one, that, as will indeed naturally be the case, one can incorporate the single experiences one remembers in the desired way here or there, as though one had written on paper: a, b, c, d.—There is now an experience one knows belongs under d, another under f, another belongs under a,—so that one is to a certain extent independent of the sequence of the thoughts as they are afterwards to be presented, as regards this collecting of the experiences. |

| One preaches to them, in some way, Marxism, or some such thing. Then one will, of course, be understood. But there is nothing of interest in being understood in this way. Otherwise one will indeed very soon have the following experience—concerning this experience one must be quite clear—: if one speaks today to a proletarian gathering so that they can at least understand the terminology—and that must be striven for—, then one will notice particularly in the discussion, that those who discuss have understood nothing. |

| Speaking must be learned to a certain extent by means of understanding how to bring to the lecture the thinking which lies behind it, and the experience which lies before it, in a proper relationship. |

| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture III

13 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

|---|

Along with the tasks which one can set oneself in a certain realm as a speaker it will be a question at first of entering in the appropriate way into the material itself which is to be dealt with. There is a twofold entering into the material, in so far as the message about this material is concerned in speaking. The first is to convert to one's own use the material for a lecture so that it can be divided up—so that one is as it were placed in the position of giving the lecture a composition. Without composition a talk cannot really be understood. This or that may appeal to the listener about a lecture which is not composed: but in reality a non-composed lecture will not be assimilated. As far as the preparation is concerned, it must therefore be a matter of realizing: every talk will inevitably be poor as regards its reception by the listeners which has merely originated in one's conceiving one statement after the other, one sentence after the other, and going through them to a certain extent, one after the other, in the preparation. If one is not in the position, at least at some stage of the preparation, of surveying the whole lecture as a totality, then one cannot really count on being understood. Allowing the whole lecture to spring, as it were, from a comprehensive thought, which one subdivides, and letting the composition arise by starting out from such a comprehensive thought comprising the total lecture,—this is the first consideration. The other is the consulting of all experiences which one has available out of immediate life for the subject of the lecture,—that is, calling to mind as much as possible everything one has experienced first-hand about the matter in question,—and, after one has before one a kind of composition of the lecture, endeavoring to let the experiences flow here or there into this composition. That will in general be the rough draft in preparing. Thus one has during the preparation the whole of the lecture before one as in a tableau. So exactly does one have this tableau before one, that, as will indeed naturally be the case, one can incorporate the single experiences one remembers in the desired way here or there, as though one had written on paper: a, b, c, d.—There is now an experience one knows belongs under d, another under f, another belongs under a,—so that one is to a certain extent independent of the sequence of the thoughts as they are afterwards to be presented, as regards this collecting of the experiences. Whether such a thing is done by putting it onto paper, or whether it is done by a free process without having recourse to the paper, will determine only that he who is dependent upon the paper will speak worse, and he who is not dependent upon the paper will speak somewhat better. But one can of course by all means do both. But now it is a matter of fulfilling a third requirement, which is: after one has the whole on the one hand—I never say the ‘skeleton’—and on the other hand the single experiences, one has need of elaborating the ideas which ensue to the point that these things can stand before the soul in the most complete inner satisfaction. Let us take as an example, that we want to hold a lecture on the threefold order. Here we shall say to ourselves: After an introduction—we shall speak further about this—and before a conclusion—about which we shall also speak—the composition of such a lecture is really given through the subject itself. The unifying thought is given through the subject itself. I say that for this example. If one lives properly, mentally, then this is valid actually for every single case, it is valid equally for everything. But let us take this example near at hand of the threefolding of the social organism, about which we want to speak. There, at the outset, is given that which yields us three members in the treatment of our theme. To deal with, we shall have the nature of the spiritual life, the nature of the juridical-state life, and the nature of the economic life. Then, certainly, it will be a question of our calling forth in the listeners, by means of a suitable introduction,—about which, as mentioned, we shall speak further—a feeling that it makes sense to speak about these things at all, about a change in these things, in the present. But then it will be a matter of not immediately starting out with explanations of what is to be understood by a free spiritual life, by a juridical-states life founded on equality, by an economic life founded on associations, but rather of having to lead up to these things. And here one will have to lead up through connecting to that which is to hand in the greatest measure as regards the three members of the social organism in the present—what can therefore be observed the most intensively by people of today. Indeed, only by this means will one connect with what is known. Let us suppose we have an audience, and an audience will be most agreeable and sympathetic which is a mixture of middle-class people, working-class people—in turn with all possible nuances—, and, if there are then of course also a few of the nobility—even Swiss nobility,—it doesn't hurt at all. Let us therefore assume we have such a chequered, jumbled-up audience, made up of all social classes. I stress this for the reason that as a lecturer one should really always sense to whom one has to speak, before one sets about speaking. One ought already to transpose oneself actively into the situation in this way. Now, what will one have to say to oneself to begin with about that which one can connect with in a present-day audience, as regards the threefold social organism? One will say to oneself: it is extraordinarily difficult in the first place to connect onto concepts of an audience of the bourgeois, because in recent times the bourgeoisie have formed extraordinarily few concepts about social relationships, since they have vegetated thoughtlessly to some extent as regards the social life. It would always make an academic impression, if one wanted to speak about these things today out of the circle of ideas of a middle-class audience. On the other hand, however, one can be clear about the fact that exceptionally distinct concepts exist concerning all three domains of the social organism within the working-class population,—also distinct feelings, and a distinct social volition. And it means that it is nothing short of the sign of our present time, that precisely within the proletariat these qualified concepts are there. These concepts are to be handled by us, though, with great caution, since we shall very easily call forth the prejudice that we want to be partisan in the proletarian direction. This prejudice we should really combat through the whole manner of our bearing. We shall indeed see that we immediately arouse for ourselves serious misunderstandings if we proceed from proletarian concepts. These misunderstandings have revealed themselves in point of fact constantly in the time when an effect could still be brought about in middle-Europe, from about April 1919 on, for the threefolding of the social organism. A middle-class population hears only that which it, has sensed for decades from the fomenting behavior of the working- class, out of certain concepts. How one views the matter oneself is then hardly comprehended at all. One must be clear that being active in the world at all in the sense, I should like to say, of the world-order has to be grasped. The world-order is such—you have only to look at the fish in the sea—, that very, very many fish eggs are laid, and only a few become fish. That has to be so. But with this tendency of nature you have also to approach the tasks which are to be solved by you as speakers; even if only very few, and these little stimulated, are to be found to begin with at the first lecture, then actually a maximum is attained as regards what can be attained. It is a matter of things that one stands so within in life, as for instance the threefolding of the social organism, that what can be accomplished by means of lecturing may never be abandoned, but must be taken up and perfected in some way, be it through further lectures, be it in some other way. It can be said: no lecture is really in vain which is given in this sense and to which is joined all that is required. But one has to be absolutely clear about the fact that one will actually also be completely misunderstood by the proletarian population, if one speaks directly out of that which they think today in the sense of their theories, as these have persisted for decades. One cannot ask oneself the question for instance: How does one do it so as not to be misunderstood?—One must only do it right! But for this reason it cannot be a matter of putting forward the question: Then how does one do it so as not to be misunderstood?—One tells people what they have already thought anyhow! One preaches to them, in some way, Marxism, or some such thing. Then one will, of course, be understood. But there is nothing of interest in being understood in this way. Otherwise one will indeed very soon have the following experience—concerning this experience one must be quite clear—: if one speaks today to a proletarian gathering so that they can at least understand the terminology—and that must be striven for—, then one will notice particularly in the discussion, that those who discuss have understood nothing. The others one usually doesn't get to know, since they do not participate in the discussions. Those who have understood nothing usually participate after such lectures in the discussions. And with them one will notice something along the following lines.—I have given countless lectures myself on the threefolding of the social organism to, as they are called in Germany, “surplus-value social democrats,” independent “social democrats,” communists and so on.—Now, one will notice: if someone places himself in the discussions and believes himself able to speak then it is usually the case that he answers one as though one had really not spoken at all, but as though someone or other had spoken more or less as one would have spoken as a social-democratic agitator thirty years ago in popular meetings. One feels oneself suddenly quite transformed. One says to oneself roughly the following: Well, can it then be that the misfortune has befallen you, that you were possessed in this moment by old Rebel? [Note 1] That is really how you are confronted! The persons concerned hear even physically nothing else than what they have been used to hearing for decades. Even physically—not merely with the soul—even physically they hear nothing other than what they are long used to. And then they say: Well, the lecturer really told us nothing new!—Since they have, because one was obliged to use the terminology, translated the whole connection of the terminology right-away in the ear—not first in the soul—into that which they have been used to for a long time. And then they talk on and on in the sense of what they have been used to for a long time. *** Speaking cannot be learned by means of external instructions. Speaking must be learned to a certain extent by means of understanding how to bring to the lecture the thinking which lies behind it, and the experience which lies before it, in a proper relationship. Now, I have, today tried to show you how the material first has to be dealt with. I have connected with what is known, in order to show you how the material may not be created out of some theory or other, how it must be drawn out of life, how it must be prepared so as to be dealt with in speaking. What I have said today everyone should now actually do in his own fashion as preparation for lecturing. Through such preparation the lecture gains forcefulness. Through thought preparation—preparing the organization of the lecture, as I have said at the beginning of today's remarks: from a thought which is then formed into a composition—, by this means the lecture becomes lucid, so that the listener can also receive it as a unity. What the lecturer brings along as thinking he should not weave into his own thoughts.—Since, if he gives his own thoughts, they are, as I have already said, such that they interest not a single person. Only through use of one's own thinking in organizing the lecture does it become lucid, and through lucidity, comprehensible. By means of the experiences which the lecturer should gather from everywhere (the worst experiences are still always better than none at all!) the lecture becomes forceful. If, for example, you tell someone what happened to you, for all it matters, as you were going through a village where someone nearly gave you a box on the ear, then it is still always better if you judge life out of such an experience, than if you merely theorize.—Fetch things out of experience, through which the lecture acquires blood, since through thinking it only has nerves. It acquires blood through experience, and through this blood, which comes out of experience, the lecture becomes forceful. Through the composition you speak to the understanding of the listener; through your experience you speak to the heart of the listener. It is this which should be looked upon as a golden rule. Now, we can proceed step by step. Today I wanted more to show first of all in rough outline how the material can be transformed by degrees into what it afterwards has to be in the lecture. Tomorrow, then, we resume again at three o'clock.

|

| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture IV

14 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

|---|

| —To stand up and lecture without stage-fright and with sympathy for one's own speaking is something that ought to be refrained from, since under all circumstances, the results thus achieved would be negative. It leads to lecturing becoming sclerotic, to ossification, and to capsulated talk, and belongs to the elements that ruin the sermon for people. |

| There, it is really a matter of not being in love with one's own way of thinking and feeling, but rather of feeling averse toward what one would like to say on the topic, and what one actually brings up. This can be done if one understands how to hold back one's own opinion, one's own annoyance or excitability, and can get across into the other person's mind. |

| The lecture is the fourth of the Speakers' Course, published in German under the title: Anthroposophie. soziale Oreigliederung und Redekunst. (Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach 1971.) |

| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture IV

14 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

|---|

One has to accustom oneself to speak differently on every soil, if one intends to be active as a lecturer ... Thus, a talk is to be formulated differently, depending on whether it is delivered here in Switzerland, in Germany, or whether at this or that time. One would, of course, have to speak again quite differently in England or in America. What can be done from here, in Europe, in regard to these two countries, can only be a sort of substitute. It is good, for example, if Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage [The Threefold Social Order] is translated, it is good if it is widely distributed; but, as I have said from the beginning, the really proper thing finally would be if the Kernpunkte were written quite differently for America and for England. For both Switzerland and Central Europe, it can be taken quite literally, word for word, the way it stands. But for England and America it would really have to be composed quite differently, because in those countries one addresses people who, first of all, have the opposite attitude of what existed, for instance, in Germany in April of 1919. In Germany the opinion prevailed that something new would have to come, and to begin with it would suffice if one knew what this were. There wasn't the strength to comprehend it, but there was the feeling that what this rational innovation might be, ought to be known. Naturally, in all of England and America not the slightest sense of this exists anywhere. The only concern there is how to secure and save the old. The question is how properly to secure the old. The old values are good! One must not shake the traditional foundations. I am aware, of course, that when anything like this is said, it can be replied: Yes, but there are so many progressive movements in the Western hemisphere!—Still, all these progressive movements, regardless of whether their content is new, are reactionary and conservative in so far as their management is concerned. There, the feeling that things cannot continue the way they have gone until now, must first be called forth. *** Things must everywhere be sought out in the concrete. ... I would like to show how an elasticity of concepts for these things [rights relationships] has to be acquired—how one has to point out both sides of a question,—and how one must be able to dispose oneself first, in order to have the necessary fluency to speak in front of people. There is another reason why a lecturer of today must be aware of such things. Most of the time, he is condemned to speak in the evening, when he wants to present something concerning the future. This means that he has to make use of the time when people really prefer to be either in the concert hall or in the theater. Thus, the lecturer must be absolutely clear that he is speaking to an audience that, according to the mood of the hour, would be better off in the concert hall, the theater, or some other place,—but not in fact down there, where it is supposed to listen, while above, a lecturer talks about things vouchsafed for the future. One must he aware of what one is really doing, down to the last detail. For, what does one in fact do when addressing an audience such as one is mostly condemned to speak in front of nowadays? Quite literally, one upsets the listener's stomach! A serious speech has the peculiarity of adversely affecting the pepsin, of not allowing the stomach juices to take effect. A serious lecture causes stomach acidity. And only if one is oneself in such a mood that one can present a serious talk, at least inwardly, with the necessary humor, can the stomach juices be assisted again. A lecture has to be presented with a certain inner lightness,—with a certain modulation, with a certain enthusiasm; then one aids the stomach juices. Then one neutralizes what one inflicts on the stomach in the time when we normally have to lecture today. The threefold social order is not being served, but rather stomach specialists, when people speak in all gravity, with heavy expressive manner, pedantically, on three-folding. It must be done with a light touch and matter-of-factness or else one does not further the threefold social order but the stomach specialists. It is just that there are no statistics available on the number of people who have to go to stomach specialists after they have listened to pedantic lectures! If there were statistics on these things, one would be astonished at the percentage among patients of stomach specialists who are eager lecture-goers nowadays. I must call attention to these things, because the time is drawing near when it must be known how the human being actually lives.—How seriousness affects his stomach, how humor affects his stomach juices; how, let us say for example, wine is like a kind of cynic who doesn't take the whole human organism seriously, but plays with it. If the human organism were approached with human concepts rather than with the wishy-washy concepts of today's science, it would be observed all over how every word and every world-relation calls forth an organic, almost chemical effect in the human being. Knowing such things makes lecturing easier too. Whereas there is otherwise a barrier between speaker and audience, this barrier ceases to exist if it is to some extent perceived how the stomach juices curdle, and eventually become sour in the stomach and impair the stomach walls, in the case of a pedantic talk. Occasionally there is the opportunity of seeing it: though less in lecture-halls of universities,—there, the students protect themselves by not listening! From all this, you can see how much depends on the mood in lecturing,—how much more important—preparing the atmosphere, having it in hand, is, than to get the lecture ready word for word. He who has prepared himself often for the correct mood need not concern himself with the verbal details to a point where, at a given moment, the latter would make him the upsetter of stomach juices. Various things—if I may so express it—go to make up a duly equipped speaker. I should like to present them at this particular point because an explanation of “rights concepts” requires much that has to be characterized in this direction. [In another part of this lecture, Rudolf Steiner had already discussed aspects of justice not having to do with the art of lecturing.—Note by translator.] I would like to present this now, before talking tomorrow about the interweaving of the “economic elements” in speaking. An anthroposophist once brought the well-known philosopher, Max Dessoir (1867–1947)—whom you also perhaps know—along one evening, to the Architektenhaus in Berlin, when I was to hold a lecture there. This one-time friend of Max Dessoir said afterwards, “Oh, that Dessoir didn't respond after all!—I asked him how he had liked the lecture and he replied: ‘Well, you know, I'm a lecturer myself, and anyone who is himself a speaker can't listen properly; he has no opinion on what another lecturer says!’ ”—Now, I did not need to form a judgement about Dessoir after this declaration; I had other opportunities for that, indeed I wouldn't have done so based on this utterance, since I could not know at all whether it was really true, or whether, as usual, Dessoir had lied this time also. But assuming it were true: what would it be a proof of?—That at any rate the one who holds such a view can never become an adequate speaker. A person can never become a good speaker who likes to speak, who likes to hear himself talk, and attaches special importance to his own speaking. A good speaker really always has to endure a certain reluctance when he is to speak. He must clearly feel this reluctance. Above all, he should much prefer listening to another speaker, even the worst, to speaking himself. I know very well what I say with this statement, and I well realize how difficult it is for some of you to believe me in this. But it is so. Of course, I concede that there are other pleasures in the world than listening to poor speakers. But at all events, speaking oneself ought not to belong to these other greater pleasures. One must even feel a certain urge to hear others; even enjoy listening to others. For it is really through listening that one becomes a speaker, not through love of speaking oneself. A certain fluency is acquired through speaking, but this has to proceed instinctively. What makes one a speaker is actually listening, developing an ear for the distinctive traits of other speakers, even if they are poor ones. Therefore, I shall answer everyone who asks me how best to prepare himself to become a good speaker: he should hear and especially read—I have explained the difference between hearing and reading—he should hear and read the lectures of others! (That can after all be done, since the nuisance prevails of printing lectures.) In this way one acquires a strong feeling of distaste for one's own speaking. And this distaste for one's own speaking is actually what enables one in fact to speak adequately. This is extraordinarily important. And for those people who don't yet manage to view their own speaking with antipathy, it is good at least to retain their stage-fright.—To stand up and lecture without stage-fright and with sympathy for one's own speaking is something that ought to be refrained from, since under all circumstances, the results thus achieved would be negative. It leads to lecturing becoming sclerotic, to ossification, and to capsulated talk, and belongs to the elements that ruin the sermon for people. I would truly not be speaking about lecturing in the sense of the task of this course if I were to enumerate rules of speaking to you, taken from some old book on rhetoric, or from copied, old rhetorical speeches. Rather, I would like to enjoin upon you, out of living experience, what one should really always have at heart when one wants to affect one's fellow-men by means of lecturing. Things certainly alter somewhat if one is forced into a debate—if, I should like to say, a certain rights-relationship between person and person arises in the discussion. But in the discussion, through which rights-relationships could be learnt most beautifully, this projecting in of general rights-concepts into the relationship which prevails between two people hardly plays a role today. There, it is really a matter of not being in love with one's own way of thinking and feeling, but rather of feeling averse toward what one would like to say on the topic, and what one actually brings up. This can be done if one understands how to hold back one's own opinion, one's own annoyance or excitability, and can get across into the other person's mind. Then this will be fruitful even in the debate when a statement must be rejected. Of course, one can not simply reiterate what the other person says, but one can appropriate from him what is needed for an effective debate. A striking example is the following: ( It is retold in the latest issue of Dreigliederung; I experienced it more than twenty years ago.) The delegate Rickert delivered a speech in the German Reichstag, in which he reproached Bismarck for changing his political alignment. He pointed out that Bismarck had gone along with the Liberals for a time, turning afterwards to the Conservatives. He gave an impressive speech, which he summarized in the metaphor, that Bismarck's politics amounted to trimming one's sails to the wind. Now, you can imagine what an effect it has inwardly, in terms of feeling, when such an image is used in a hall of parliament [—the proper German translation for parliament is really Schwatzanstalt.—] Bismarck, however, rose and with a certain air of superiority, to begin with, turned the things he had to say against delegate Rickert. And then he projected himself into the other as he always did in similar cases, and said, “Rickert has reproached me for trimming my sails to the wind. But pursuing politics is somewhat like navigating. I would like to know how one can steer properly if one does not want to adjust to the wind! A real sailor, like a real politician, must obviously adjust according to the wind in steering his course,—unless, possibly, he wants to make wind himself!” You can see, the image is picked up and used, so that the arrow in fact hits back at the archer. In a debate it is a matter of taking things up, of getting things from the other speaker. Where a frivolous illustration is concerned, the matter is comprehensible. But one will also be able to do it in seriousness; seeking out from the opponent himself what unravels the matter! As a rule it will not be much use merely setting one's own reasons against those of the opponent. In a debate one should be able to attune oneself as follows: The moment the debate gets going one should be in a position to dispose of everything one has known hitherto, drive it all down into the unconscious, and actually only know what the speaker whom one has to reply to, has just said. Then one should squarely exercise one's talent for setting aright what the speaker has said! Exercise the talent for setting aright! In debate it is a matter of taking up immediately what the speaker says, and not simply pitting against it what one already knew long ago. If that is done, as happens in most debates, the debate actually ends inconsequentially, in fact it comes to nothing. One has to be aware that in a debate one can never refute someone. It can only be demonstrated that a speaker either contradicts himself or reality. One can only go into what he has set forth. And that will be of immense importance if it is made use of as the basic principle for debates or discussions. If a person only wants to say in the debate what he has known before, then certainly it will be of no significance at all when he puts it forward after the speaker. This once stared me in the face in a particularly instructive way. In Holland I was invited on my last trip also to give a lecture on Anthroposophy before the Philosophical Society of the University of Amsterdam. The chairman there was, naturally, already of a different opinion than I. There was no doubt at all that, if he were to engage in the debate, he would say something quite different than I would. But it was equally clear that what he said would ultimately make no difference as regards my lecture, and that my lecture would have no particular influence on what he would say, based on what he knew anyhow. Hence, I considered he did things quite cleverly. He raised what he had to say not subsequently in the debate, but in advance! What he did add later in the debate to his preliminary words he could equally have presented beforehand, at the start—it would not have changed matters a bit. One must not cherish any illusions about such things. Above all a lecturer should familiarize himself very, very thoroughly with human relationships. But, if things are to have an effect, one cannot allow oneself any illusions about human relationships. Above all—I should like to tell you this today, since it will provide a certain basis for the next lectures—above all, one should not surrender to illusions about the effectiveness of talks! Inwardly, I always have to get into a terribly humorous frame of mind when well-meaning contemporaries say again and again: It's not a matter of words, it's a matter of deeds! I have heard it declaimed again and again at the most inopportune points, not only in dialogues, but also from various podiums: Words don't count; actions count! As far as what happens in the world in the way of actions, everything depends on words! For those able to get to the bottom of the matter, no actions take place at all that have not been prepared in advance by someone or other through words. But you will realize that the preparation is something quite subtle! For, if it is true—and it is true!—that through pedantic, theoretical, abstract, Marxist speaking one actually upsets people's stomach juices—whereby the stomach juices infect the rest of the organism—then outside actions, which very much depend on the stomach juices, are the consequence of such bad speeches. The stomach juices flow into the rest of the organism, when dispersed. On the other hand again, when people only act as jokers, stomach juices are produced incessantly, which really works like vinegar,—and vinegar is a frightful hypochondriac. But people will keep on being entertained, and what flows nowadays in public is a continuous whirl of fun-making. The joking-around of yesterday is still not digested, when the fun-making of today makes its appearance. With that, the digestive juices of yesterday go sour and become like vinegar. The human being will in turn be entertained today. He can make merry. But by the way he takes his place in public life, it is really the hypochondriacal vinegar which operates there. And this hypochondriacal vinegar is then to be met with! In fact, in saloons it is the Marxist speakers who ruin people's stomachs. And if people then read the Vorwaerts [—apparently a comic paper], then this is the means by which the upset stomach must be put in order again. That is a very real process! ... It must be known how the realm of speaking takes its place within the realm of actions. The untruest utterance—because from false sentimentality (and everything stemming from false sentimentality is untrue!)—the untruest utterance vis-a-vis speaking is: “Der Worte sind genug gewechselt, lasst mich auch endlich Taten sehen!” [“The words you've bandied are sufficient: 'tis deeds that I prefer to see.”—Faust, Prelude on Stage.] That can certainly stand in a passage of a drama. And where it stands it is even justified. But when it is torn out of context and made out to be a general dictum, then it may be “correct,” but good it is quite certainly not! And we should learn not merely beautiful, not merely correct, but also goodspeaking. Otherwise we lead people into the abyss, and can in any case not confer with them about anything worthy of the future.

|

| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture V

15 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

|---|

| [Note 1] You will have understood from that, how preparing oneself for the content of such a lecture, one can proceed. Now, one can also prepare oneself for the form of delivery by immersing oneself into the thoughts and feelings. |

| If you imagine how at that time everything should have been transported from one territory into the other this would have been a difficult process under modern-day conditions. But owing to the manner in which Japan and China were placed within the whole world economy, it could be done this way. |

| If somebody believes that he could become a speaker without putting any value on this, then he labors under the same misconception as a human soul that has arrived at the point between death and a new birth, when it once again will descend to the earth, and does not want to embody itself because it does not want to enter into the moulding of the stomach, the lungs, the kidney, and so forth. |

| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture V

15 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I have tried to characterize how one can formulate a lecture on the threefold order from out of one thought, and then arrange it in sections. What one can generally say concerning the whole social organism, as well as references to what can occur in the first two realms—namely that of the spiritual life and that of the judicial, the body politic was contained in what I said. [Note 1] You will have understood from that, how preparing oneself for the content of such a lecture, one can proceed. Now, one can also prepare oneself for the form of delivery by immersing oneself into the thoughts and feelings. We shall perhaps understand each other best if I say that the preparation should be such that we try hard first to sense and then to utter what is related to the spiritual life in a more lyrical language (without, of course, resorting to singing, recitation, or some such thing),—in a lyrical manner of speech, with quiet enthusiasm, so that one demonstrates through the way of delivering the matters that everything one has to say concerning the spiritual life comes from out of oneself. One should by all means call forth the impression that one is enthusiastic about what one envisions for the spiritual part of the social organism. Naturally, it must not be false, mystical, sentimental enthusiasm; a made-up enthusiasm. We achieve the right impression if we prepare ourselves first in imagination, in inner experience—even so far as to modulation—how, approximately, something like that could be said. I say specifically, “how, approximately, something like that could be said,” for the reason that we should never commit ourselves word for word; rather what we prepare is, in a sense, a speech taking its course only in inward thoughts; and we are certainly ready to re-formulate what we finally come out and say. But when we speak about rights-relationships, we should make the attempt to speak dramatically. That implies: when we lecture about the equality of men, discussing it by means of examples, we should try as much as possible to put ourselves into the other person's position with our thinking. For instance, we should call to mind the image of how a person who seeks work, asserts his right to work in the sense of Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage (the threefold social order). By making it evident that on one hand we are speaking from the other person's position, from out of his assertion of rights, we should then make it evident how through a slight change in the tone of voice we pass on to the topic of how one ought to meet such an assertion out of general humanitarian reasons. So it is dramatic speaking, very strongly modulated, dramatic lecturing, that calls forth the impression in listeners that one could think one's way into the souls of other persons; that is the manner we should employ in speaking about the rights-relationships. When lecturing on economic conditions, the main point is that we speak directly from experience. If, in the spirit of the threefold social organism, one speaks about economic relationships, one should not permit the belief to arise that there even could be such a thing as a theoretical political economy. Instead, one should limit the main discussion to describing cases taken from the economic life itself; either cases that one repeats, or cases that one construes as to how they should be or could be. But with the latter cases—saying how they should or could be—one must never neglect to speak out of economic experience. Actually, when lecturing on the economic life, one should speak in an epic style. Particularly, when presenting what is written in the Kernpunkte, one should speak as if one had no preconceived ideas at all concerning the economic life, and had no notions that this should be thus and so; instead, one should speak as if one were informed on all and everything by the facts themselves. One can evoke a certain feeling, for example, that it is correct to permit the transfer of the administration of monetary funds from one who is not involved in it himself anymore, to somebody who once again can participate in it. But one can only speak about something like that if one presents it to people by means of descriptions of what takes place if there are legacies merely due to blood-relationships, or what can take place when such a transfer is occasioned in the way it is described in the Kernpunkte. Only by placing such a matter before people in a living way, as if one were copying reality, can one speak in such a way that the speech truly stands within the economic life. And just in this way, one can make the idea of “associations” [Note 2] comprehensible and plausible. One will make it plausible that an individual person really knows nothing about the economic life; that if he wants to arrive at a judgement as to what must be done in the life of the economy, he is basically completely dependent on communicating with others. A sound economic view can only emerge from groups of people and one is therefore dependent on associations. Then, one will perhaps meet with comprehension if one calls attention to the fact that much of what exists today actually came out of ancient, instinctive associations. Just consider for a moment how today's abstract market brings things together, whose combination and redistribution to the consumer cannot be surveyed at all. But how has one arrived at this market-relationship in the first place? Basically, from the instinctive association of a number of villages located around a larger township, at a distance that one could travel back and forth on foot in one day, where people exchanged their products. One did not call that an association. One did not coin any word for it, but in reality it was an instinctive association. Those people who here came together for the market were associated with all of those who lived in the surrounding villages. They could count on a set circulation of goods that resulted from experience. Therefore they could regulate production according to consumption in truly alive relationships. There certainly existed such associative conditions in such primitive economies; they just didn't call themselves that. All this has become impossible to over-see, with the enlargement of the economic territories. In particular, it has become senseless in regard to the world economy. The world economy which has come into being only in the last third of the 19th century, has reduced everything into an abstract realm; that is, it has reduced everything in the economic life to the turn-over of money or its monetary value, until this reduction has proven its own absurdity. Indeed, when Japan fought a war with China and Japan won the war, one could very simply pay the war reparations by way of the Chinese Minister's handing a check to the Japanese Delegate, which the latter then deposited in a bank in Japan. This is an actual course of events. There were values contained in this check, which is money and has monetary value. It represented values. If you imagine how at that time everything should have been transported from one territory into the other this would have been a difficult process under modern-day conditions. But owing to the manner in which Japan and China were placed within the whole world economy, it could be done this way. However, all this has led itself to a point of absurdity. In the dealings between Germany and France, it has proven itself to be impossible. [Note 3] I am therefore of the opinion that the state of affairs can best be explained out of the economic relationships themselves, and then one can explain the necessity for the associative principle. Once again, one should have to divide this subject matter regarding the economic life in a certain way, and one would have to pass on to several concluding sentences of which I have already said that they again should be conceived verbatim or at least almost word for word. So, how will the preparation for a speech appear, in fact? Well, one should try one's best to get into the situation or the subject that the audience is prepared for, by formulating the opening sentences in a way one considers necessary. One will have greater difficulty in the case of completely unprepared listeners; less difficulty, if one addresses a group that one finds already involved in the matter, at least possessing the corresponding feelings concerning the assertions one makes. Then, one will neither write down the rest of the speech nor jot down mere catch-words. Experience shows that neither the verbatim composition nor the mere noting down of catch-words leads to a good speech. The reason for not writing down the speech is because it ties one down and easily causes embarrassment when the memory falters; this is most frequently the case when the speech is written down word for word. Catch-words easily mislead one to formulate the whole preparation too abstractly. On the other hand, if one needs to have such a support, what one should best write down and bring along as notes are a number of correctly formulated sentences that serve as catch-phrases. They do not make the claim that one delivers them in the same way as a part of the speech; instead, they indicate: first, second, third, fourth, and so on; they are extracts, so to speak, so that from one sentence perhaps ten or eight or twelve will result. But one should write such sentences down. One should therefore not write down, “spiritual life conceived as independent”; instead, “the spiritual life can only thrive if it freely works independently out of itself.” (Catch-phrases, with other words.) If you do something like this, you will then have the experience yourself that owing to such catch-phrases, you can in a relatively short time most readily attain to a certain facility of speaking freely, a speaking that only contains the ladder of catch-phrases. Concerning the conclusion, it is often very good if, in a certain sense, at least gently, one leads back to the beginning; if therefore the end, in a sense, contains something that, as a theme, was also contained in the beginning. And then, such catch-phrases readily give one the opportunity to really prepare oneself in the way indicated above by having noted these sentences down on one's piece of paper. So, let us say, one ponders the following: what you have to say for the spiritual life must have a sort of lyrical nature within you; what you have to say concerning the rights-relationships must have a kind of dramatic character in your mind; and what concerns the economic life must live in your mind in a narrative, epic form; a quiet, narrative, epic character. Then, the desire, as well as the skill, to word the catch- phrases in the formulation that I have indicated, will indeed begin to arise instinctively. The preparation will result quite instinctively in such a way that the manner in which one speaks merges indeed into what one has to say concerning the subject. For this it is, however, necessary to have brought one's command of language to the level of instinct, so that one indeed experiences the speech-organs the way one would, for instance, feel the hammer, if one wanted to use the hammer for something. That can be achieved, if one practices a little speech-gymnastics. It's true, isn't it, when one practices gymnastics, those are not movements that are later executed in real life; but they are movements that make one flexible and dextrous. Similarly, one should make the speech-organs pliable and adroit; but making the latter pliable and dextrous is something that must be accomplished so that it goes together with the inner soul life, and so that one learns to be aware of the sound in speaking. In the seminar courses that I held over two years ago in Stuttgart for the Waldorf school teachers, I put together a number of such speech exercises that I now want to pass on to you. They are mostly of a kind that, by their content, does not prevent one from learning to merge oneself purely into the element of speech; they are only designed for practicing speech-gymnastics. If one tries again and again to say these sentences aloud, but in such a way that one always probes: how does one best use his tongue, how does one best use his lips so as to produce this particular sequence of sounds?—then one makes oneself independent of speaking and, instead, places that much more value on mental preparation for lecturing. I shall now read you a number of such sentences whose content is often senseless, but they are designed to make the speech-organs pliable and fit for public speaking. [Note 4]

is the easiest one.

One should increasingly try, along with the sequence of sounds, to make the organs of speech pliable; to bend, to hollow, to take possession of them [Note 5]

It is naturally not enough to say something like this once, or ten times; but again and again and again, because even if the speech-organs are already pliable, they can become still more so. An example that I consider to be particularly useful is the following:

With this, one has the opportunity to regulate the breath in the pauses, something one has to pay attention to and that can be particularly well done through such an exercise. In a similar way, not all the letters, nor all the sounds, have the same value for this practicing. You make progress if you take the following, for example:

If you succeed in finding your way into this sequence of sounds, you gain much from it. When one has done such exercises, then one can also try to do those exercises that cannot but result in bringing a mood into the speaking of the sounds. I have tried to give an example of how the sounds can pour into the mood in the following:

and now it passes more into the sounds, through which, here in particular, the mood in the sound itself is held fast:

You will always discover, when you do these exercises in particular, how you are able, without letting the breath disturb you, to regulate the breathing by simply holding yourself onto the sounds. In recent times, one has thought up all kinds of more or less clever methods for breathing and for all kinds of accompanying aspects of speaking and singing, but actually, all of those are no good, because speech with everything that belongs with it, with the breath, too, should by all means be learned through actual speaking. This implies that one should learn to speak in such a way that, within the boundaries that result from the sound sequence and the word relationships, the breath also regulates itself as a matter of course. In other words, one should only learn breathing during speech—in speaking itself. Therefore, the exercises of speech should be so designed that, in correctly feeling them regarding their sounds, one is obliged—not by the content but by the sounds—to formulate the breath correctly because he experiences the sound correctly. What the verse below represents, points once again to the content of the mood. It has four lines; these four lines are arranged so that they are an ascent, as it were. Each line causes an expectation, and the fifth line is the conclusion and brings fulfilment. Now one should really make an effort to execute this speech movement that I have just characterized. The verse goes like this:

There you have the fifth line representing the fulfillment of that escalating expectation that is evoked in the first four lines. ***

One can also attempt to, well, let me say, bring the mood of the situation into the sounds, into the mode of speaking, the how of speech. And for that I have formulated the following exercise. One should picture a sizable green frog that sits in front of him with its mouth open. In other words, one should imagine that one confronts a giant frog with an open mouth. And now, one should picture what sort of reactions, effects, one can have regarding this frog. There will be humor in the emotion as well as all that should be evoked in the soul in a lively manner. Then, one should address this frog in the following way:

Picture to yourself: that a horse is walking across a field. The content does not matter. Naturally, you must now imagine that horses whistle! Now you express the fact that you have here in the following manner:

and then you vary that by saying it this way:

And then—but please, do learn it by heart, so that you can fluently repeat the one version after the other—there is a third version. Learn all three by heart, and try to say them so fluently that during the speaking of one version you will not be confused by the other. That is what counts. Take as the third form:

Learn one after the other, so that you can do the three versions by heart, and that one never interferes when you say the other. Something similar can be done with the following two verses:

and now the other version:

Again, learn it by heart and say one after the other! One can achieve smooth speech if one practices something like the following:

One has to accustom oneself to say this sound sequence, ‘Nur renn ...’. You will see what you gain for your tongue, your organs of speech, if you do such exercises. Now, such an exercise that lasts a bit longer, through which this flexibility of speech can be attained—I believe actors have already discovered afterwards that this was the best way to make their speech pliable:

And then: one occasionally requires presence of mind in direct speech. One can acquire it by something like the following:

Then, for further acquisition of presence of mind in speaking, the following two examples can be placed together:

The ‘Wecken weg’ is in there, too, but as a sound-motif, thus:

The following example is useful for putting some muscle into speech, so that one is in a position, in speaking, to slap somebody down in a discussion sometimes (something that is quite necessary in speaking!):

Then, for somebody who stutters a little, the following two examples should still be mentioned:

For everyone who stutters, this example is good. When stuttering, one can also say it in the way below:

The point is, of course, that the person who stutters must make a real effort. One should by no means believe that what I want to call speech-gymnastics, can or should only be practiced with sentences that are meaningful for the intellect. Because in those sentences that contain sense for the intellect, the attentiveness for the meaning instinctively outweighs anything else too much, so that we do not rely correctly on the sounds, the saying. And it is really necessary that, in a certain sense, we tear speaking loose from ourselves, actually manage to separate it from ourselves. In the same way as one can separate writing from one's self, one can also tear speaking loose from oneself. There are two ways to write for the human being. One way consists of man's writing egotistically; he has the forms of the letters in his limbs, as it were, and lets them flow out of his limbs. One emphasized such a style of writing for a certain length of time—it is probably still the same today—when one gave lessons in penmanship for those who were to be employed in business offices or people like that. I have, for example, observed at one time how such a lesson in writing was conducted for employees of commercial establishments so that the persons in question had to develop every letter out of a kind of curve. They had to learn swinging motions with the hand; then they had to put these motions down on paper; this way, everything is in the hand, in the limbs; and one is not really present with anything but the hand in writing. Another form of writing is the one that is not egotistical; it is the unselfish style of writing. It consists of not really writing with the hand, as it were, but with the eye; one always looks at it and basically draws the letter. Thus, what is in the formation of the hand is of importance to a lesser degree: one really acts like one does when sketching, where one is not the slave of a handwriting. Instead, after a while, one has difficulty in even writing one's name the same way one has written it just the time before. For most people it is so terribly easy to write their name the way they have always written it. It flows out of their hand. But those persons who place something artistic into the script, they write with the eye. They follow the style of the lines with the eye. And there, the script indeed separates itself from the person. Then—while it is in a certain respect not desirable to practice that—a person can imitate scripts, vary scripts in different ways. I do not say that one should practice that especially, but I mean that it results as an extreme when one paints one's script, as it were. This is the more unselfish writing. Writing out of the limbs, on the other hand, is the more selfish, the egotistic way. Speech is also selfish, in most people. It simply emerges out of the speech-organs. But you can gradually accustom yourselves to experience your speech in such a way that it seems as if it floated around you, as if the words flew around you. You can really have a sort of experience of your words. Then, speaking separates itself from the person. It becomes objective. Man hears himself speak quite instinctively. In speaking, his head becomes enlarged, as it were, and one feels the weaving of sounds and the words in one's surroundings. One gradually learns to listen to the sounds, the words. And one can achieve that particularly through such exercises. That way, there is in fact not just yelling into a room anymore—by yelling, I do not mean shouting out loud only; one can yell in whispering, too, if one actually speaks only for one's own sake, the way it emerges out of the speech-organs—instead one really lives, in speaking, with space. One feels the resonance in space, as it were. This has become a fumbling mischief in certain speech-theories—theories of speech-teaching or speech-study, if you will—of recent times. One has made people speak with body-resonance, with abdominal resonances, with nasal resonances, and so forth. But all these inner resonances are a vice. A true resonance can only be an experienced one. One experiences such a resonance not by the impact of the sound against the interior of the nose; instead one feels it only in front of the nose, outside. Thus, language in fact attains to abundance. And of course, the language of a speaker should be abundant. A speaker should swallow as little as possible. Do not believe that this is unimportant for the speaker; it is rather of great significance for the speaker. Whether we present something in a correct way to people depends most certainly on what position we are able to take in regard to speech itself. One doesn't have to go quite so far as a certain actor who was acquainted with me, who never said “Freundrl” [Austrian dialect for “Friend”—note by translator] but always “Freunderl”, because he wanted to place himself into every syllable. He did that to the extreme. But one should develop the instinctive talent not to swallow syllables, syllable-forms, and syllable-formations. One can accomplish that if one tries to find one's way into rhythmic speech in such a way that, placing one's self into the whole sound-modulation, one recites to oneself:

So: it is a matter of placing one's self not only into the sound as such but into the sound-modulation, into this “growing round” and the angularity of sound. If somebody believes that he could become a speaker without putting any value on this, then he labors under the same misconception as a human soul that has arrived at the point between death and a new birth, when it once again will descend to the earth, and does not want to embody itself because it does not want to enter into the moulding of the stomach, the lungs, the kidney, and so forth. It is really a matter of having to draw on everything that makes a speech complete. One should at least put some value on the organism of speech and the genius of language as well. One should not forget that valuing the organism of speech, the genius of language, is creative, in the sense of creating imagination. He who cannot occupy himself with language, listening inwardly, will not receive images, will not be the recipient of thoughts; he will remain clumsy in thinking, he will become one who is abstract in speaking, if not a pedant. Particularly, in experiencing the sounds, the imagery in speech-formation, in this itself lies something that entices the thoughts out of our souls that we need to carry before the listeners. In experiencing the word, something creative is implied in regard to the inner organization of the human being. This should never be forgotten. It is extremely important. In all cases, the feeling should pervade us how the word, the sequence of words, the word-formation, the sentence-construction, how these are related to our whole organism. Just as one can figure out a person from the physiognomy, one can even more readily—I don't mean from what he says but from the how of the speech—one can figure out the whole human being from his manner of speech. But this how of his speech emerges out of the whole human being. And it is by all means a matter of focusing—delicately of course, not by treating ourselves like we were the patient—on the physical body. It is, for example, beneficial for somebody who, through education or perhaps even heredity, is predisposed to speaking pedantically; to try, with stimulating tea that he partakes of every so often, to wean himself from pedantry. As I have said, these things must be done with care. For one person, this tea is right; for another, the other tea is good. Ordinary tea, as I have repeatedly mentioned, is a very good diet for diplomats: diplomats have to be witty, which means having to chat at random about one thing after another, none of which must be pedantic, but instead has to exhibit the ease of switching from one sentence to another. This is why tea is indeed the drink of diplomats. Coffee, on the other hand, makes one logical. This is why, normally not being very logical by nature, reporters write their articles most frequently in coffee-houses. Now, since the advent of the typewriter, matters are a little different, but in earlier days, one could meet whole groups of journalists in coffee-houses, chewing on their pen and drinking coffee so that at last, one thought could align itself with the next one. Therefore, if one discovers that one has too much of what is of the tea-quality, then coffee is something that can have an equalizing effect. But, as was mentioned before, all this is not altogether meant, as a prescription, but pointing in that direction. And if somebody, for example, is predisposed to mix some annoying sound into his speech—let's say if somebody says, “he,” after every third syllable, or something like that—then I advise him to drink some weak senna-leaf-tea twice a week in the evening, and he will see what a beneficial effect that will have. It is indeed so: since the matters that come to expression in a lecture, in a speech, must come out of the whole person, diet must by no means be overlooked. This is not only the case in an obvious sense. Of course, one can hear by the speech whether it comes from a person who has let endless amounts of beer flow down his gullet, or something like that. This is an obvious case. He who has an ear for speech knows very well whether a given speaker is a tea-drinker or a coffee-drinker, whether he suffers from constipation or its opposite. In speech, everything is expressed with absolute certainty, and all of that has to be taken into consideration. One will gradually develop an instinct for these matters if one becomes sensitive to language in one's surroundings the way I have described it. However, the various languages lend themselves in different ways, and in varying degrees, to being heard in the surroundings. A language such as the Latin tongue is particularly suitable for the above purpose. The same with the Italian. I mean by this, to be heard objectively by the one who is speaking himself. The English language, for example, is little suited for this, because this language is very similar to the script that flows out of the limbs. The more abstract the languages are, the less suitable they are to be heard inwardly and to become objective. Oh, how in former times the German Nibelungen-song sounded:

That hears itself while one is speaking! Through such things one must learn to experience language. Naturally, languages become abstract in the course of their development. Then one must bring the concrete substance into it from within, permeate it with the obvious. Abstractly placed side by side, what a difference:

and so forth! But if one becomes accustomed to listening, this can certainly also be brought into the more modern language, and there, much can be done in speech towards the latter's becoming something that has its own genius. But for that, such exercises are required, so that listening in the spirit and speaking out of the spirit fit into one another. And so, I want to repeat the verse one more time:

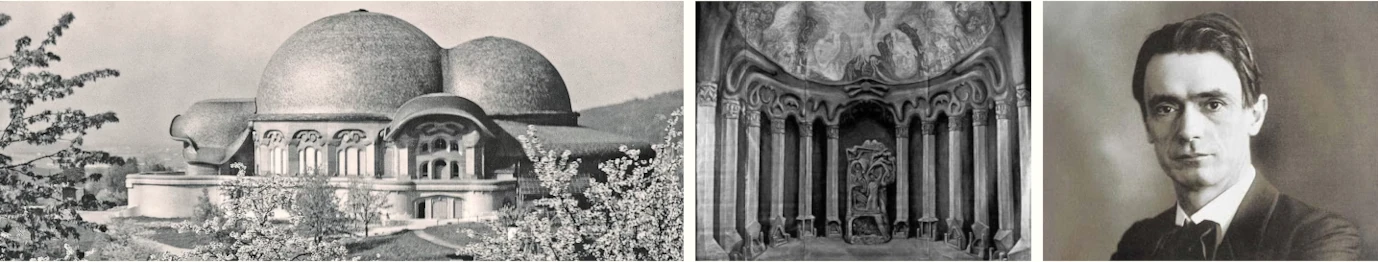

Only by placing the sound into various relationships, does one arrive at an experiencing of the sound, the metamorphosis of the sound, and the looking at the word, the seeing of the word. Then, when something like what I have described today as creating a disposition through catch-sentences, as our inner soul-preparation, is united with what we can in the above way gain out of the language, then it all works toward public speaking. One more thing is required besides all the others I have already mentioned: responsibility! This implies that one should be aware that one does not have the right to set all of one's ill-mannered speech-habits before an audience. One should learn to feel that for a public appearance one does require education of speech, a going-out of one's self, and plasticity in regard to speech. Responsibility towards speech! It is very comfortable to remain standing and to speak the way one normally does, and to swallow as much as one is used to swallow; to swallow (verschlucken), to squeeze (quetschen), and to bend (biegen) and break (brechen), and to pull (dehnen) at the words just the way it suits one. But one may not remain with this squeezing (Quetschen) and pushing (Druecken) and pulling (Dehnen) and cornering (Ecken) and similar speech-mannerisms. Instead, one must try to come to the aid of one's speaking even in regard to the form. If one supports one's speaking in this manner, one is quite simply also led to the point where one addresses an audience with a certain respect. One approaches public speaking with a certain reserve and speaks to an audience with respect. And this is absolutely necessary. One can accomplish this if, on the one side, one perfects the soul-aspect; and, on the other side, formulates the physical in the way I have demonstrated in the second part of the lecture. Even if one only has to give occasional talks, such matters still play an important part. Say, for example, that one has to give discussions on the building, the Goetheanum. Since one naturally cannot make a separate preparation for each discussion, one should basically, in that case, properly prepare oneself, the way I have explained it, at least twice a week for the talk in question. One should actually only extemporize, if one practices the preparation, as it were, as a constant exercise. Then one will also discover how, I should like to say, the outer form unites itself with the substance. And we shall have to speak about this point in particular one more time tomorrow: about the union of the form-technique with the soul-technique. The course is brief, unfortunately; one can barely get past the introduction. But I would find it irresponsible not to have said what I did say in particular in the course of these lectures.

|

| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture VI

16 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

|---|

| The artistic aspect of speaking is, in general, something that must be kept clearly in mind, the more the subject matter is concerned with logic, life-experience, and other powers of understanding. The more the speaker is appealing to the understanding through strenuous thinking, the more he must proceed artistically—through repetition, composition, and many other things which will be mentioned today. You must remember that the artistic has its own means of facilitating understanding. Take, for example, repetition, which can work in such a way that it forms a sort of facilitation for the listener. |

| This has to be said in such a way that the listener knows he is to understand the opposite. Thus, let us say, the speaker says straight out, and even in an assertive tone: Kully is stupid. |

| 339. On The Art of Lecturing: Lecture VI

16 Oct 1921, Dornach Translated by Maria St. Goar, Peter Stebbing, Beverly Smith, Fred Paddock |

|---|